* For more on Huff Duff, see Appendix 8.

* See Volume II, Appendix 15, and Volume I, Appendix 18, based on Tarrant (1989).

* Designated Submarine Squadron 50, the first boats were Barb, Blackfish, Gunnel, Gurnard, Herring, and Shad. After Torch operations, the boats and the tender Beaver were to base in Roseneath, Scotland, and conduct anti-U-boat patrols.

* See Plate 12.

* A public forecast by the Deputy Director of the U.S. Maritime Commission, Howard L. Vick-ery, that in 1942 and 1943 American yards alone would produce over 2,500 ships for 27.4 million deadweight tons. It was an accurate prediction. In 1942 and 1943, American yards produced 2,709 ships for 27.21 million deadweight tons, or 18.435 million gross registered tons.

† See Appendix 10.

* Dönitz was still unaware that usually one or more ships in every convoy had Huff Duff or of the increasingly important role shipboard and land-based Huff Duff played in convoy defense. See Appendix 8.

† Oberkommando der Kriegsmarine, i.e., naval headquarters, Berlin.

* A “bombe” was an ingenious Allied electromechanical machine, first developed by the Poles in prewar years, that was used to help break German Enigma codes. (See photo insert.)

* The story of Fish and Colossus is beyond the scope of this book. See articles in the bibliography under “Colossus.”

† For biographical and professional information on Engstrom, see Volume I, pp. 243-44 and 557.

‡ See unpublished documents in NARA, RG 457, NSA History Collection, Box 705, especially NR 1736, dated April 24, 1944, “Memorandum for the Director of Naval Communications, History of the Bombe Project,” by Joseph N. Wenger, Engstrom, and Ralph I. Meader (hereafter Engstrom Memo), and chapter 11 of George E. Howe’s United States Cryptographic History, NSA (1980). In a 1998 taped interview with the author, Eachus clarified: He and Ely flew to England, remained at Bletchley Park about three weeks, then flew back to the States with blueprints for an Enigma machine. At the specific request of Gordon Welchman, almost immediately the U.S. Navy sent Eachus back by air to Bletchley Park where he and a U.S. Navy coworker, Milton Gaschk, remained on semipermanent duty for about one year, submitting reports on various British projects at the GC&CS.

§ See Volume I, pp. 240-44.

# On May 13, 1942, Bletchley Park’s deputy director, Edward Travis, had promised in writing to deliver to the Americans “by August or September” a bombe and “a mechanic to instruct in the mainte nance and operation.”

* Redman had replaced Leigh Noyes as Director of Naval Communications in March 1942.

† The official British intelligence historian F. H. Hinsley presents a quite inaccurate account of the American decisions with respect to the number of American bombes contemplated and why. See his British Intelligence in the Second World War, vol. 2, p. 57.

* Nickname for members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), formally incorporated into the Royal Navy in 1949.

† See Beesly, Very Special Admiral (1980).

* The Ultra-Magic Deals (1992).

* The Hut Six Story (1982).

† After the war, Welchman immigrated to the United States and became an American citizen. He joined a private firm, Engineering Research Associates (ERA), which was founded by Howard Engstrom, Ralph Meader, and others to build codebreaking machines for the Navy and early commercial mainframe computers for private industry. Because in his book Welchman described technically some ways wartime Enigma was penetrated, London and Washington were furious. Washington rescinded his security clearance, thereby denying him the ability to ply his trade, and threatened to prosecute him by U.S. laws for leaking British secrets. The British writer “Nigel West” (The Sigint Secrets, 1988) wrote that the stress brought on by this governmental “harassment” aggravated a heart condition and led to his premature death in October 1985.

‡ Strong steel-mesh nets to stop or deflect submarine torpedoes.

* Owing to a defective main bearing, the battleship Tirpitz could not participate.

† The U-606 skipper, Hans Klatt, was temporarily replaced by Dietrich von der Esch of U-586, which was in refit. He brought ten of his crew to U-606, displacing a like number of that ship’s green crew. At the end of this brief patrol, Hans Dohler was appointed commander of U-606 and sailed it onward to join the Atlantic force.

* The official British naval historian writes at odds with the Admiralty assessment committee, and perhaps in error, that Faulkner killed U-88 and Onslow killed U-589. Other British naval historians have copied Roskill, but without noting the discrepancies or attempting to resolve them.

* The Luftwaffe mounted about three hundred torpedo and bombing sorties against PQ 18. The Germans lost forty-one aircraft, mostly to flak.

† The “Ritterkreuz” was the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross, a much-prized decoration in the German military. At the time of the award, Strelow’s confirmed score was seven ships for 34,914 tons.

‡ When Hoschatt returned to port, Hans-Jürgen Zetzsche, who had run his U-591 on some rocks, was given temporary command of U-378. Erich Mader soon replaced Zetzsche as permanent skipper. Zetzsche’s U-591 required two months in the Bergen shipyard to repair the damage. A Kriegsmarine Board of Inquiry sentenced Zetzsche and his quartermaster to four days confinement in quarters.

§ The Luftwaffe sank ten merchant ships, all from PQ 18. See Plate 13.

* Eighteen by aircraft alone, sixteen by U-boats alone, and nine by aircraft and U-boats combined.

* Including about a dozen boats undergoing battle-damage repairs. For Order of Battle, see Appendix 1.

† The VII U-626, commanded by Hans-Botho Bade, rammed and sank the VIIU-222, commanded by Rolf von Jessen. Only Jessen and two others survived, Jessen went to another new VII. The VII U-446, commanded by Hellmut-Bert Richard, hit a mine near Danzig and sank with the loss of twenty-three men. A freighter rammed the VIIU-450, commanded by Kurt Bohme. The IXC U-523, commanded by Werner Pietzsch, rammed Scharnhorst. Repairs to U-626, U-450, and U-523 delayed their departures to the front for several months. The U-446 was salvaged but held in the Baltic as a school boat.

‡ The U-212, U-354, U-606, U-622, and U-663 were sent for permanent duty and the U-262, U-611, and U-625 for temporary duty, but the U-625 remained in the Arctic. Two days after leaving Bergen on September 24, two Hudsons of British Squadron 48, piloted by E. Tammes and R. Horney, dropped eight depth charges near U-262, commanded by Heinz Franke, age twenty-six. The damage forced Franke to abort to Bergen. He resailed on October 3.

§ See appendices 2,4, and 5.

* For details of North Atlantic convoys, September 1942-May 1943, see Appendix 3.

* The British and Canadian groups B-5 and C-5 were serving temporarily in the Caribbean.

* The official Canadian Navy historian wrote that convoys HX 1 to HX 207 from Halifax had sailed with 8,501 ships, and SC 1 to SC 94 had sailed with 3,652 ships. Convoys SC 95 to SC 101 (from Halifax) sailed with 318 ships. All told: 12,471 vessels sailed in these eastbound convoys in three full years of operations. See Volume I, Plate 10, and Plate 13.

† For a detailed list of Allied airborne ASW units in the North Atlantic area, see Appendix 10.

* See Volume I, pp. 475-481.

† The U.S. Navy’s PBY-5A Catalinas and the Canadian Canso “A” flying boats operating in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia were fitted with retractable wheels and could therefore fly from land bases in icy winter months.

‡ See Volume I, p. 687.

* On October 29, VP 73 deployed to Morocco for Torch via Ballykelly, Northern Ireland. U.S. Navy Squadron VP 84 (Catalinas) in Argentia replaced VP 73 in Iceland and VP 82, reequipped with PV-3 Venturas, replaced VP 84 in Argentia. The Ventura was envisioned as an upgraded Hudson (top speed 318 m.p.h. versus 250 m.p.h.; pay load six depth charges versus four), but the plane was crippled with defects and deficiencies in 1942 and was therefore unsuitable for its ASW mission.

* See Volume I, p. 341.

† Coastal Command aircraft Had also sunk three U-boats in the Bay of Biscay unassisted by surface craft (U-502, U-578, U-751), and Royal Navy aircraft had sunk two (U-64, U-451). U.S. Army and Navy aircraft had sunk six others in American waters, three in cooperation with surface ships: U-94, U-153, U-166, U-576, U-654, and U-701.

* The Canadians provided seventeen corvettes for Torch.

* The 1,800-ton Coast Guard cutter Muskeget, reporting weather from a station south of Greenland. All 121 men on board perished.

* Three destroyers of the hunter-killer 20th Support Group raced to the assistance of RB 1 but had no success.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was twelve ships, including Veteran, sunk for 61,700 tons and damage to the two tankers.

* Halifax 205 to 208; Slow Convoy 98 to 102; RB 1; Outbound North and Outbound North (Slow) 126 to 134. HX 208 was the first of this type to sail from New York, on September 17. See Appendix 3.

* At the time, the Admiralty credited a Hudson of British Squadron 269 with sinking U-582 and the British destroyer Viscount with sinking U-619. However, according to Franks (1995), in the postwar reappraisal, credit for sinking both boats went to aircraft, as described herein.

† The identity of the Catalina and pilot is difficult to establish. Remarkably, four different Catali-nas (Nos. 8, 9, 10, 12) of VP 73 carried out attacks on U-boats in that area on October 5 and 6. The pilots were C. F. Swanson, M. Luke, W. Mercer, and W. B. Huey, Jr. Niestle” credits Swanson.

* Trojer’s claims in two attacks on Slow Convoy 104 were eight ships sunk fof 43,547 tons. His confirmed score was five ships sunk for 29,681 tons, the highest confirmed score of any U-boat on the North Atlantic run in the fall of 1942.

* U-boat Killer (1956).

† Bringing the number of RAF B-24s assigned to operational Coastal Command ASW squadrons to twenty-one.

‡ After U-213 and U-215, she was the third of the six clumsy Type VIID minelayers to be sunk within four months.

* This was the heaviest damage inflicted on a Halifax convoy by U-boats since the attack on Halifax 133 sixteen months earlier, from June 24 to June 29, 1941.

† Two regular warships of Escort Group C-4, the ex-American four-stack destroyer St. Croix and corvette Sherbrooke, were in the dock for refits.

* Credit for her kill went initially to Squadron Leader Terence Bulloch in a British B-24 of Squadron 120 based in Iceland, but a postwar Admiralty analysis identified the explosion of Hatimura as the likely cause.

* Squadron 145 was preparing to reequip from Hudsons to Cansos, but this would take quite some time. The new Squadron 162 was scheduled for Cansos.

† Halifax 209 to 212; Slow Convoy 103 to 107; Outbound North and Outbound North (Slow) 135 to 141. See Appendix 3.

‡ U-216, U-353, U-412, U-582, U-597, U-599, U-619, U-627, U-658, U-66L The VIIC U-132, sunk on November 5 in action against Slow Convoy 107, would raise the loss of VIICs to eleven.

§ U-89, U-254, U-257, U-382, U-440, U-595, U-607, U-609, U-620, U-664. The U-620, shifted to the Gulf of Cadiz, was at sea on this patrol for sixty days.

# Including special convoy RB 1.

* Stated in the more commonly cited deadweight tons: 1,886,000.

† See chart in Volume I, p. 666.

‡ See Appendix 2. Twenty of thirty-three U-boats that sailed in September and twenty of forty that sailed in October.

* At the time of the award (December 29, 1942), his confirmed score, all on U-106, was eleven ships for 73,413 tons, plus damage to the tanker Salinas and an American freighter for 12,885 tons.

* After changing into civilian clothes, Janowski made his way to New Carlisle with two heavy suitcases, and checked into a hotel to bathe and rest for a few hours. He then checked out, paying in obsolete Canadian bills, and boarded a local train, the first stage in a journey to Montreal. A suspicious hotel clerk notified police, who arrested Janowski at the first train stop, nine miles away. Some sources say the Canadians “turned” Janowski and used him and his radio gear and codes to transmit disinformation to Berlin.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was sixteen ships for 74,184 tons.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was thirteen ships for 71,704 tons, plus damage to five for about 30,000 tons.

* See Plate 2.

* The TMA was an anchored or moored mine that could be launched from a torpedo tube in depths to 885 feet. Owing to the weight and bulk of the anchor and chain, its warhead was only 474 pounds.

* Injured during an Allied air raid on Bremen, Gysae returned to U-177 from the hospital on crutches. Hence the” crew adopted a crutch for its conning-tower emblem.

* Four Type VIIs, nine Type DCs, and four Type IXD2 U-cruisers. Five of the seventeen boats were commanded by Ritterkreuz holders. These were, in addition to Gysae and Lüth in the U-cruisers, Karl Friedrich Merten and Ernst Bauer in the Type IXCs U-68 and U-126, respectively, and Peter Cre-mer in the Type VII U-333.

* West Point-educated son of the general commanding all Army forces in the central Pacific under Admiral Nimitz.

* These and other details of the event, as recorded at the time by Hartenstein, are taken from an English translation of the war diary of U-156, which was presented at Dönitz’s trial in Nuremberg and included as an appendix in the published record of the war crimes trial of Heinz Eck et al. (See bibliography listing for Cameron.)

* The exact fate of the Italian POWs and the approximate number who drowned locked in holding pens, if any, has not been established. The assertion here of callous inhumanity is taken from an excellent but incomplete account of the disaster, The Laconia Affair (1963), by a French author, Léonce Peillard. In several other places in his account, Peillard states (or quotes others as stating) that the Polish guards refused to unlock the pens. Elsewhere, he writes that hundreds of fear-crazed Italian POWs escaped by rushing the bars en masse and smashing them down. He depicts one Laconia officer leading a group of Italian POWs from the hold to the boat deck. Citing Italians, both Hartenstein and Schacht logged—and informed Dönitz by radio—that the British had badly mistreated the Italian POWs.

† Harden and crew were awarded Air Medals for the “destruction” of one submarine (U-156) and “probable destruction” of another (U-506).

* All survivors rescued by Gloire were interned at Casablanca. Torch forces released the British and Polish survivors, but the fate of the Italians is not known. If not already repatriated, they were recaptured by Torch forces. In gratitude for the French role in the rescue of the Italians, the Axis offered to release an equal number of imprisoned Frenchmen named by the crews of the French ships. On June 10, 1944, the Germans turned over 385 Frenchmen listed by Gloire crewmen, but failed to act on lists submitted by Annamite and Dumont.

* At the time of the award, Hartenstein’s confirmed score was seventeen ships for 88,198 tons, including Laconia.

† The four Type IXs of group EISBÄR, preparing to attack Cape Town, two of the four Type IXD2s bound for the Indian Ocean, five Type IXs, and three Type VIIs patrolling independently.

* Credit to Grossi for sinking two battleships was withdrawn after the war. His confirmed bag in the war was two ships sunk for 10,309 tons and one ship damaged for 5,000 tons. One of the ships sunk was the Spanish neutral Navemar, which had delivered a load of 1,120 Jewish refugees from France to New York and was returning empty to Spain.

* See Volume I, pp. 673-74.

* The Italian skipper Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia in Da Vinci sank four freighters for 26,000 tons.

† In addition to the two supply boats, these were Bauer in U-126; Heyse in U-128; Schendel in U-134; Achilles in U-161; two boats patrolling Brazilian waters, Thilo’s U-174 and Dierksen’s U-176; and two returning Eisbär boats, Helmut Witte’s U-159 and Emmermann’s U-172.

‡ Three other attack boats that proceeded from the replenishment to Brazilian waters sank five other ships.

* At the time of the award, Heyse’s confirmed score was twelve ships sunk for 83,639 tons. Achilles’s confirmed score was eleven ships sunk for 58,518 tons, plus damage to seven ships for 44,427 tons, including the light cruiser Phoebe, which was repaired in an American shipyard and thus out of action for months.

† The four IXCs each set out with twenty-two torpedoes, the four IXD2s each with twenty-four. The Cagni, which had eight bow tubes and six stern tubes, carried an astonishing total of forty-two Italian-made, 17.7” torpedoes on this patrol.

* Not having heard from Sobe since September 18, and unaware that he had reached the Cape, Dönitz logged that there was “no clue” as to the U-179’s loss. Some staffers wrongly presumed that U-179 had been sunk by Allied aircraft near Ascension Island.

* Within a period of about one month, Axis submarines in the South Atlantic sank four big British liners in service as troopships for about 84,000 tons: Laconia, Oronsay, Orcades, and Duchess of Atholl The 11,330-ton British Abosso, sunk on October 30 by U-575 in the North Atlantic, raised British troopship losses to five by November 1, 1942. Seldom mentioned, these troopship losses stand in stark contrast to the nearly perfect safety record of troopships escorted by American warships.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was fourteen ships for 77,530 tons.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was sixteen ships for 82,135 tons.

† At the time of the award, his confirimed score was twenty-seven ships for 170,175 tons. He stood eighth in tonnage sunk among all U-boat skippers.

* The Benlomond was en route from Cape Town to Dutch Guinea (Surinam). Hit by two torpedoes, she sank instantly about 750 miles east of the mouth of the Amazon River. There was one survivor, Poon Lim, a Chinese mess steward. After a record 133 days on a raft, he was rescued by a Brazilian fishing trawler near Belem, Brazil.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was eighteen ships for 100,793 tons. It was noted that with this award, four of the five skippers of the attack boats originally assigned to group Eisbär, including Hartenstein in U-156, won a Ritterkreuz, and the fifth skipper, Merten, won Oak Leaves to his Ritterkreuz.

‡ The patrols averaged 122 days or about four months. Witte in U-159 and Emmermann in U-172 were at sea 135 and 131 days, respectively. All boats refueled twice, once outbound and once inbound.

* This raised the loss of British troopships in this foray to five.

† At the time of the award, Lath’s confirmed score on the ducks U-9 and U-138, the IX U-43, and U-181 was twenty-nine ships for 147,256 tons, including the French submarine Doris.

* The American Jordan Vause, in U-boat Ace (1990).

† Not counting troopships assigned to Torch forces or those sunk in the Mediterranean, or the Abosso sunk in the North Atlantic, but including Oronsay, sunk by Archimede near Freetown. These lamentable troopship losses are not described in full by the official British naval historians or by other British authors. For details, see Plate 4.

* The VIIC U-136, the VIID minelayer U-213, and the IXD2 U-cruiser U-179.

* The veterans U-73, U-81, U-431, U-565, and three of the four new arrivals, U-458, U-605, and U-660.

* “Ducks” were very small (141-foot, 300-ton) German submarines designed for North Sea operations and the Training Command. Six Type IIB ducks (U-9, U-18, U-19, U-20, U-23, U-24) were dismantled and floated on river barges to Galatic, Romania, reassembled, and organized into Combat Flotilla 30, which operated from Constanta. According to Rohwer (Successes), the little flotilla sank six confirmed Soviet freighters for 28,303 tons and maybe two minesweepers and a submarine. No ducks returned from the Black Sea.

† See Volume I, pp. 337-38.

* See Volume I, pp. 652-53.

† Petard’s crew reached six hundred feet with some missiles of a ten-charge pattern by plugging the holes in the hydrostatic pistols with soap.

* For their bravery, Fasson and Grazier were posthumously awarded the George Cross, and Canteen Assistant Tommy Brown was awarded the George Medal. When it was learned that Brown was only sixteen years old and had falsified his age by a year in order to join the Royal Navy, he was discharged immediately. In 1944, Brown was killed attempting to rescue his younger sister, who was trapped in a burning building.

† See Fighting Destroyer (1976), by one of Petard’s officers, G. Gordon Connell. In a candid afterword, Rear Admiral G. C. Leslie, R.N., wrote that only a “few” destroyer captains in the Royal Navy went through the war “without a breakdown” and that during Thornton’s command of Petard, “the strain became too great to bear.” Later, however, Thornton was given command of another destroyer.

‡ At the time of the award, his confirmed score was five ships sunk for 14,542 tons, including the Australian sloop Parramatta.

* Ernst-Ulrich Brülier’s U-407, Quaet-Faslem’s U-595, Günter Jahn’s U-596, Albrecht Brandi’s U-617, and Walter Going’s U-755.

* Eisenhower’s naval aide, Harry C. Butcher, noted in his diary, My Three Years with Eisenhower (1946), that Churchill said: “Kiss Darlan’s stern if you have to, but get the French Navy.”

† When a British naval task force leapfrogged about one hundred miles east to Bougie on November 11-14, Axis aircraft sank three big troop transports, a cargo vessel, and two warships and badly damaged the new 8,000-ton monitor Roberts, which mounted two 15” guns, eight 4” guns, and many smaller weapons.

* These four U.S. Navy carriers were hurried conversions of big tankers. They were longer than the “jeep” carriers (about 555 feet versus 495 feet) and carried more aircraft (thirty-two versus fifteen to twenty-five). They had two elevators to the hangar deck and two catapults.

* Dakar fell to the Allies without a fight on November 23. Subsequently, the unfinished battleship Richelieu and a half dozen French cruisers and other vessels sailed to the United States for refits and modernization.

† Down went seventy-seven warships: the old battleship Provence, two modern battle cruisers, Dunkerque and Strasbourg, seven cruisers, thirty-two destroyers, sixteen submarines, including Caiman and Fresnel, which had just escaped from North Africa, a seaplane tender, and eighteen sloops and smaller craft. Four other submarines sailed from Toulon: Glorieux, Iris, Marsouin, and Casabianca. Iris reached Spain, where she was interned for the rest of the war. The other three reached Algiers.

* Six veteran boats undergoing refit, overhaul, upgrade, or battle-damage repair could not sail: U-83 and U-97 at Salamis; U-371 and U-375 at Pola; U-453 and U-562 at La Spezia. However, by December 1, 1942, five of these six were at sea in combat operations, except for the badly damaged U-97.

* Kreisch added that U-boats were not, as was customary, to give highest priority to aircraft carriers and battleships but to amphibious forces and merchant ships.

* An attempt by the Germans to establish a temporary forward U-boat base at Cagliari, on the southern coast of Sardinia, failed. On November 11, a British submarine sank the U-boat mother ship, Bengasi, off Cape Ferrato, northeast Sardinia. Lost were forty G7e electric torpedoes, a year’s supply of food for U-boat crews, plus U-boat fuel and lube oil.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was only five ships for 13,000 tons. The fact that his was the only U-boat to sink Torch warships—the destroyers Martin and Isaac Sweers—doubtless figured strongly in the award.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score, all on U-81, was five ships for about 40,000 tons, including, of course, the British carrier Ark Royal, plus five sailing ships. His new ship was the IXD2 U-847, the first of a special series of six U-cruisers (U-847 to U-852) that were to be commanded only by Ritterkreuz holders, including Wilhelm Rollmann and Heinz-Otto Schultze. Almost immediately after commissioning U-847, however, Guggenberger was transferred to France to take command of an IXC whose skipper had been sacked.

† A submerged noisemaker, designed to confuse enemy sonar operators.

* The white flag was probably raised to deter the killing and wounding of German crewmen and to invite rescue of the survivors. Doubtless the loyal, defiant, and resourceful von Tiesenhausen would have scuttled upon the arrival of a surface ship.

† Allied forces also sank three Italian submarines in the Mediterranean in the first two weeks of November: Antonio Sciesa by United States Army Air Forces aircraft, Granito by the British submarine Saracen (which had earlier sunk U-335 near the Shetlands), and Emo by the British ASW trawler Lord Nuffield.

* The other, U-258, aborted owing to the “illness” of the skipper, Wilhelm von Mässenhausen, who temporarily left the boat on returning to France. She was replaced by U-257, commanded by Heinz Rahe, who also aborted owing to the “illness” of the engineering officer and a serious leak.

† And the U.S. submarine defense of the Philippines in 1941 and Midway Island in 1942.

† Twenty-two Italian submarines deployed against Torch forces. These sank or polished off four ships at or near Bougie Bay: the 16,600-ton troopship Narkunda, the 13,482-ton troopship Awatea, the 2,400-ton antiaircraft cruiser Tynwald, and the 850-ton minesweeper Algerine. Awatea and Tynwald had previously been damaged by the Luftwaffe, Jürgen Rohwer wrote, and “settled to the bottom.”

* In all of 1942, U-boats in the Mediterranean sank twelve warships, eleven of them British: the aircraft carrier Eagle; two light cruisers, Naiad and Hermione; five destroyers (Gurkha, Jaguar, Martin, Partridge, Porcupine), and three Hunt-class destroyers (Blean, Grove, Heythrop). The other warship was the Dutch destroyer Isaac Sweers.

† “Experience with the First Bomber Command in antisubmarine operations since March indicates that the effective employment of air forces against submarines demands rapid communication, mobility, and freedom from the restrictions inherent in command systems based upon area responsibility “ (emphasis added).

* Stalking the U-boat (1994).

* Three squadrons of Hudsons (48, 233, 500), one squadron of Catalinas and Sunderlands (202), and one squadron (179) of Leigh Light-equipped Wellingtons.

* These ASW B-24s were stripped of standard gear required for high-altitude daylight bombing—armor, self-sealing fuel tanks, engine turbochargers, machine-gun turrets, and so on—and were fitted with four forward-firing 20mm cannons. A part of the bomb bay was modified to carry extra fuel, greatly extending the range but cutting the depth-charge payload to about sixteen.

† Confusingly, on March 1, 1943, the consolidated unit was redesignated USAAF 2037th Wing (Provisional) and finally, on June 21, 1943, 480th Group.

* Kessler claimed one hit on the Queen Elizabeth but failed to specify it was the ocean liner, not the battleship of the same name, thereby causing considerable confusion at U-boat headquarters. The hit could not be confirmed. Among the passengers on the liner was the senior codebreaker and bombe designer Alan Turing, who, as related, was embarked on an official visit to the United States.

* From November 1, 1942, U.S. Navy Patrol Wings, usually composed of a headquarters and three aircraft squadrons, were redesignated Fleet Air Wings or Fairwings. The one in Morocco, Fair-wing 15, was commanded by George A. Seitz.

* The Admiralty initially credited the kill of U-98 to a Hudson. This wrong assessment led to confusion and to further wrong assessments and misplaced kill credits at this time. To avoid further confusion the Admiralty errors are not detailed here.

† The seven other “jeep” and light carriers survived Torch but were not immediately available for Atlantic convoy escort as originally intended. The Admiralty was not satisfied with the aircraft fuel-handling systems on the American-built “jeep” carriers, to say nothing of the ill-performing main-propulsion plants. Hence, upon arrival in the British Isles, Archer, Biter, and Dasher went into shipyards for extensive modification, or “anglicization.” Ironically, Dasher’s modified fuel-handling system blew up and sank the carrier in the Firth of Clyde on March 27, 1943. The two survivors, Archer and Biter, finally began convoy escort in April 1943. Three of the four American semi-”jeeps,” Sangamon, Suwannee, and Chenango (heavily damaged in a storm on the homeward voyage), went from Torch to the States to the Pacific. The fourth, Santee, remained in the Atlantic Fleet for ASW missions, but she, too, . had first to undergo refit, modernization, and aircrew training, which required about six months.

* U-108, U-218, U-263, U-413, U-509, U-566, U-613, U-752.

† U-91, U-92, U-185, U-519, U-564.

‡ See Volume I, pp. 395-404.

* Counting the 279 persons lost on the destroyer tender Hecla and those on the damaged destroyer Marne, Henke had caused the deaths of about one thousand persons on this single anti-Torch patrol.

† At the time of the award, his confirmed score was ten ships for 71,677 tons.

‡ Believing Hororata had run into the island of Flores in the Azores for repairs, Dönitz directed Walter Schug in the Type VIIB U-86 to secretly cut her mooring chains and when she drifted into international waters, sink her. However, Schug could not find Hororata, and the scheme was abandoned.

* In addition, on the night of December 11-12, Italian frogmen swimming from the submarine Ambra with attachable, timed explosives, sank one 1,500-ton freighter and damaged three others for 18,800 tons in Algiers harbor.

† See Volume I, Appendix 6 and Volume II, Appendix 7.

* The Norwegian corvette Potentilla was credited with the kill on November 20, but in a postwar analysis, the Admiralty concluded that that assessment was “doubtful.” During the chaotic action on the night of November 17-18, any of the several corvettes could have done the deed. The Norwegians saw—and reported—oil and debris that night, but no corvette had time to recover the debris to substantiate a kill.

* Halifax 213 to 216; Slow 108 to 110; Outbound North (Fast and Slow) 142 to 149.

† The ship in Slow Convoy 109, the 9,100-ton American tanker Brilliant, was only damaged. However, she sank under tow on December 25, 1943, so she is shown as a loss in November.

‡ Including, as related, fifteen ships for 82,800 tons from Slow Convoy 107, which sailed in late October; they were sunk in November.

§ In his analysis, Jürgen Rohwer put the loss from Axis submarines at 131 Allied ships for 817,385 tons, of which 120 for 737,675 tons were accounted for by German U-boats. The tables in Tarrant (1989), which are utilized in this account, put the figure for Axis submarines at 126 ships for 802,160 tons.

# Engage the Enemy More Closely (1991).

* Churchill also invited President Roosevelt’s two most senior American advisers in London, Averell Harriman and Admiral Stark, to attend the committee meetings.

* Two new VIIs, U-302, commanded by Herbert Sickel, and U-629, commanded by Hans-Helmut Bugs, were assigned directly to the Norway Arctic command to conform to Hitler’s minimum force requirements. Another, U-272, commanded by Horst Hepp, collided in the Baltic with U-634, commanded by Hans-Günther Brosin. Both boats sank, but U-634 was later salvaged. Seventy-nine of 108 crewmen were rescued including Hepp and Brosin. Twenty-nine died.

† The eleven boats provisionally released to Dönitz had first to be overhauled and modified for Atlantic duty. As a result, the transfers were slow: four in January 1943, one in March, two in April, etc.

* The deflector was by then a standard modification on production-line boats. Upon receiving Thurmann’s report, Dönitz canceled the modification and ordered that all deflectors of this type be removed.

* Waters apparently adhered to the Coast Guard view that the December 15 kill was improbable. In contrast, official Coast Guard historians have accepted the Admiralty’s assessment. The U-626 was the last of eighteen U-boats sunk by American forces in their first year of the war, 1942—one of them, U-94, shared by U.S. Navy aircraft and the Canadian corvette Oakville. Unassisted Navy aircraft accounted for seven; unassisted destroyers accounted for one; unassisted Army Air Forces aircraft accounted for three; Army aircraft and a Navy destroyer shared one; Navy aircraft and a merchant ship shared one; Coast Guard forces (three cutters, one aircraft) sank the other four.

* In the year 1942, Canadian forces sank nine U-boats, including U-94, shared with the U.S. Navy. Including U-94, Canadian surface ships accounted for six; unassisted aircraft, for three.

* Reinhard Hardegen had commanded her on his two celebrated Drumbeat patrols to the United States. She sailed from Germany on December 5, after six months of battle-damage repairs. Her new commander, Horst von Schroeter, had been Hardegen’s first watch officer.

* Halifax 217 to 220; Slow Convoy 111 to 114; Outbound North and Outbound North (Slow) 150 to 157.

† Including, notably, the 18,700-ton British liner/troopship Ceramic.

‡ See Appendix 3. In the same two-month period, U.S. shipyards alone turned out well over five times these losses: 214 ships of 1.3 million gross tons.

* British forces sank three other boats in the Bay of Biscay or the approaches to the Strait of Gibraltar: the VIIs U-98, U-411, and the IXC U-517.

* Grey Wolf, Grey Sea (1970).

* Bleichrodt did not return to combat. In total ships and tonnage sunk (28 for 162,491 tons) he stood tenth among all U-boats skippers in the war.

† In early 1943, Patrol Squadrons VP 32, VP 34, VP53, VP 74, VP 81, VP 83, VP 94, and six of the VP 200-VP 212 series served in Fairwing 11.

‡ Fairwing 16 absorbed four patrol squadrons from Fairwing 11: VP 74, VP 83, VP 94, and VP 203. Both wings were equipped with Catalinas, Mariners, and Venturas, the latter two aircraft types plagued with serious defects.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was nineteen ships for 77,144 tons.

* As one step in an apparent attempt to terrorize British ship crews, on March 11, 1943, a German radio propagandist bragged about Nissen’s attack on the C. S. Flight. He said that Nissen poured “streams of tracer bullets” and lobbed hand grenades into the sails and rigging, forcing the “Negro crew” to leap into the sea. At Dönitz’s trial at Nuremberg, British prosecutors introduced a précis of the broadcast as one more example of alleged atrocities committed by U-boats. Probably because no witnesses could be found to corroborate the hearsay radio broadcast, the British prosecutors did not pursue this incident further.

* Patrol Squadron VP 83 of Fairwing 11, based at Natal, had been reinforced early in January 1943 by two other U.S. Navy patrol squadrons from Fairwing 11, Squadrons 74 and 94. U.S. Army Air Forces aircraft also patrolled this area.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was twenty-seven ships for 125,520 tons.

* See Volume I, Appendix 17.

† From September 1 to December 31, 1942, the Allies lost thirty-three tankers to Axis submarines, nineteen in North Atlantic convoys.

* See Plate 5.

* As related, Nissen in U-105, homebound from Trinidad, later found and sank the hulk.

* Initially Seehund was composed of five experienced IXC40s and the new IXD2 U-cruiser U-182. The IXC40s were to be supported by the tanker U-459.

* Heydemann in U-575 claimed his original twelve internal torpedoes had sunk six ships for 41,000 tons, none of which could be confirmed.

† On January 16, Herbert Schneider in U-522, who had sunk two tankers in TM 1 for 16,867 tons and damaged another, was awarded a Ritterkreuz. At the time of the award his confirmed score was six ships for about 37,000 tons, plus damage to two others.

* The IXC U-160, which sailed in early January, replaced U-522 in group Seehund, but U-511 was not replaced. Hence, Seehund was reduced to five boats: U-160, the IXCs U-506, U-509, and U-516, and Clausen’s IXD2 U-cruiser U-182, all supported by the tanker U-459.

† If Auffermann in U-514 rather than Nissen in U-105 is credited the 8,100-ton tanker British Vigilance of TM 1, the expanded Delphin group sank eleven ships for 89,000 tons.

* The first RAF “Thousand Plane Raid” hit Cologne on the night of May 30-31, 1942. The bombers killed 474 people, destroyed 3,300 homes, and left 45,000 homeless. Two further “Thousand Plane Raids” followed: at Essen on June 1 (956 aircraft) and at Bremen on June 25 (904 aircraft). On analysis, the second two raids were deemed to be failures and, partly as a consequence, Bomber Command mounted no other “Thousand Plane Raids” in 1942.

† Heavy-bomber production in Britain and the United States was still relatively modest. In the month of July 1942, for example, British factories turned out 179 such aircraft, fifty less than planned. In 1942 the United States produced 2,576 heavy bombers, an average of 214 per month, which was about 6 percent of the total 42,000 aircraft deliveries. In compliance with the American Army-Navy Agreement of March 1942, the Army Air Forces grudgingly began delivery of B-24s to the American Navy in August. By the end of 1942, the Navy had received fifty-two B-24s, but Admiral King had sent all of them to the Pacific. In 1943 the Americans produced 9,393 heavy bombers, an average of 783 per month, which was about 14 percent of the 67,000 aircraft deliveries.

* Bomber Command had already raided Rostock, Lübeck, Emden, Bremen, Hamburg, and Wilhelmshaven. As was learned after the war, none of the hundreds of planes involved in these raids had hit a U-boat building yard or any U-boat.

* Bomber Command managed only three raids on German cities with U-boat building yards in October, and no raids in November or December, in part because of terrible weather. Allied intelligence authorities characterized these three raids as “small and inconsequential.” In a memo of January 4, 1943, Churchill groused that “the Americans have not yet succeeded in dropping a single bomb on Germany.”

* Loch Ewe was a more convenient and comfortable! departure port for Murmansk convoys than Iceland, especially in the icy winter months. Ships from the United States bound for Murmansk crossed the Atlantic in fast Halifax convoys, which sailed from New York.

* The official stenographer wrote that it was “an hour and a half.’

* This message was widely repeated, not only on Various naval Engima nets, but also in lower codes, such as the “dockyard” net, Werft, thus providing Allied codebreakers with cribs.

† Dönitz wrote that he spent most of his time as C in C, Kriegsmarine, at a “somewhat isolated” headquarters in Koralle, about twenty miles north of Berlin center, between Bernau and Eberswalde.

* In the numerous naval battles associated with the fighting on Guadalcanal, the Americans incurred very heavy warship losses: two fleet carriers {Wasp, Hornet); five heavy cruisers (Astoria, Chicago, Quincy, Northampton, Vincennes); two light cruisers (Atlanta, Juneau); fifteen destroyers; three destroyer/transports; and one troopship. The Australians lost the heavy cruiser Canberra. Many other Allied warships were damaged, some heavily. The Japanese lost one fleet carrier (Ryujo), two battleships (Hiei, Kirishima), three heavy cruisers (Kako, Furutaka, Kingugasa), one light cruiser (Yura), eleven destroyers, six submarines, and twelve troop transports. Comparative warship losses: Allies 29, Japanese 36.

* Allied and neutral merchant-ship losses are Admiralty figures, which require refinement. In boasting about American ship production, officials such as War Shipping Administrator Admiral Emory S. (Jerry) Land invariably used the larger “deadweight” tonnage figures rather than the smaller “gross” tonnage figures. Hence, on January 5, 1943, Land announced that the United States had built 746 ships (later corrected to 760 ships) for 8 million tons in 1942. The failure of some Allied officials and some historians of the Battle of the Atlantic to draw a distinction between deadweight and gross tonnage figures led to considerable confusion during the war and later. (The gross tonnage of a ship is arrived at by measuring the cubic capacity of the enclosed spaces of the ship and allowing one gross ton for every 100 cubic feet. The deadweight tonnage of a ship is the weight [in tons of 2,240 lbs.] of the cargo she can carry, including fuel, stores, and water.)

† American yards were to produce 1,949 ships of 19.2 million deadweight or 13 million gross tons in 1943.

* UGF 1 (thirty-eight ships, fifty-six escorts) was the Torch assualt convoy, Task Force 34. UGF 2 (twenty-four ships, ten escorts) sailed from the United States on November 13, 1942, and ar rived at Casablanca on November 18, designated Task Force 38. There was no UGS 1. UGS 2 (eighty- three ships including escorts) sailed on November 25, designated Task Forces 37 and 39. Thereafter UGF and UGS convoys sailed about every twenty-five days.

† See Appendix 15 and Plate 5.

* At the time of the Casablanca conference, January 1943, only twenty-four aircraft of Bomber Command were equipped with H2S radar sets: twelve Stirlings of Squadron 7, and twelve Halifaxes of Squadron 38. The H2S radar was first used in combat over Germany on the night of January 30-31 by six pathfinder aircraft (four Stirlings, two Halifaxes), which found Hamburg in foul weather and marked it with incendiaries for the main bomber formations.

§ He officially replaced Philip de la Ferte” Joubert on February 5, 1943.

# See Appendix 14.

* See Appendix 13.

* In The Defeat of the German U-boats (1994).

* See Appendix 3.

* See Plate 1.

† Mishaps and setbacks continued in the Baltic, delaying the flow of new U-boats to the Atlantic. The worst setback was the delay of the XIV tanker U-490, commanded by Wilhelm Gerlach, age thirty-eight. She sank off Gotenhafen during workup and was in salvage and repair for eight months, a blow to the thin, hard-pressed Atlantic refueler fleet. The VII U-231, commanded by Wolfgang Wenzel, age thirty-five, failed her tactical exercise and had to repeat the test. During another tactical exercise, her sister ship, U-232, commanded by Ernst Ziehm, age twenty-eight, collided with U-649, commanded by Raimund Tiesler, age twenty- three. The U-649 sank with the loss of thirty-five of forty-six crew. Rescued, Tiesler commissioned another VII. The new VII V-416, commanded by Christian Reich, age twenty-seven, hit a mine laid by British aircraft and sank. She was salvaged but relegated to a school boat. Reich commissioned another VII. The new VII U-421, commanded by Hans Kolbus, age twenty-three, also hit a British mine and was severely damaged. The U-643, commanded by Hans-Harald Speidel, age twenty-five, incurred a horrendous series of mechanical difficulties, including a battery explosion, which delayed her readiness for over six months. Rammed the previous fall in a tactical exercise by the IXC40 U-168, commanded by Helmut Pich, U-643 finally sailed after months of repairs.

* Including the XB U-119, which laid an unsuccessful minefield off Iceland.

† Including the VIIDs U-217 and U-218, which laid unsuccessful minefields off the coast of England, and U-303, U-410, U-414, and U-616, which entered the Mediterranean.

‡ Including the XB U-118, which laid a successful minefield off Gibraltar Strait, and U-224, which entered the Mediterranean.

§ Including the VII U-455 and the XB U-117, which laid minefields off Casablanca on April 10 and April 11. These fields resulted in the sinking of one 3,800-ton French freighter and damage to two other Liberty-type vessels.

* Including XB U-119, which laid a minefield off Halifax that sank one 3,000-ton freighter and damaged another of 7,100 tons.

* Merchant Shipping and the Demands of War (1955).

† In this instance, the calculations of Allied shipping losses by Jürgen Rohwer closely match those of the Admiralty.

* Includes one experienced boat with a new skipper.

† Includes eight experienced boats with new skippers.

‡ Includes four experienced boats with new skippers.

§ Includes U-71 and U-704, retired to Training Command.

# Includes two experienced boats with new skippers.

* Includes U-108, retired to Training Command.

† Known as SAM ships, 182 were actually transferred to the British.

‡‡ From February 1943, nominally Admiral Friedeberg, C in C, U-boats, but in reality Rear Admiral Eberhard Godt, head of U-boat operations; his first staff officer, Günther Hessler; Adalbert Schnee; Peter Cremer; and a few others.

* Including four transfers from the Arctic: U-376, U-377, U-403, U-456.

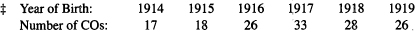

† See especially Rolf Giith (with documentation by Jochen Brennecke) in the German periodical Schiffund Zeit, no. 28 (1988) and Dr. Timothy P. Mulligan, “German U-boat Crews in World War II: Sociology of an Elite,” Journal of Military History (April 1992), as corrected in reprints. Invaluable to the study of this controversy is a list of all U-boat commanders with their date of birth compiled and published by R. Busch and H. J. Roll in the German periodical Der Landser Grosshand, based on data provided by Horst Bredow and staff at the U-boat Archive, Cuxhaven.

* A more sophisticated version, the T-5, called Zaunkdnig (Wren), which was designed to “home” straight at the propeller noise of a target and hit the propeller, was under development.

* The Admiralty credited Clark with sinking the new U-337, en route to group Jaguar. In a revised edition of his Search, Find and Kill (1995), Franks writes that that “kill” was actually the failed attack on U-632 and that U-337, commanded by Kurt Ruwiedel, was lost to unknown causes.

* Thurmann was credited with sinking fifteen confirmed ships for 85,500 tons.

* The Admiralty originally credited a B-24 of the newly arrived American Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Squadron 2, piloted by William L. Sanford, with the kill of U-519. In a postwar review, Admiralty historians concluded that British convoy escorts, Eva and the heavy cruiser Cornwall, sank U-519. Later yet they declared U-519 lost to unknown causes.

* In convoy Outbound North (Slow) 160, huge seas capsized and sank the commodore’s flagship, Ville de Tamatave, with the loss of all hands

† Including two from the Arctic: U-405 and U-591. ;

* As examples, AA, AB, AC, AD and CA, CB, CD represented specific Type VIIs; BA, BB, BC, BD and DA, DB, DC represented specific Type IXs. MA might be the XB (minelayer) U-116, MB the U-117, etc.

* See NARA unpublished documents in Record Group 457. These are the tens of thousands of pages of the files from the “Secret Room,” a huge store of information in English, so utterly complete for 1943, 1944, and 1945 that one could almost write a history of the U-boat war from them alone. The files also contain English translations of all messages between U-boat Control and the U-boats at sea and vice versa.

* One of the corvettes attempted to sink Daghild With gunfire, but failed. Rolf Struckmeier in U-608 finally sank the hulk with a torpedo.

† When this rescue story leaked, it was widely publicized in the wartime media, which featured Raney (who later rose to vice admiral) and Keene—and the dog “Rickey.” See Webster article, “Someone Get That Damned Dog!”

* Von Forstner’s confirmed bag in Slow Convoy 118 was six ships for 32,446 tons, plus a Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI) from Daghild. His confirmed score at the time of the award, all on U-402, was thirteen ships sunk for 63,409 tons, plus severe damage to two tankers for 16,731 tons, which were abandoned and sunk by other U-boats.

† According to Franks in Search, Find and Kill (1995), originally it was erroneously believed that in this attack Sanford sank U-519.

* See Volume I, p. 301.

* Credit for these kills remains uncertain. Originally the Admiralty credited a B-24 of Squadron 120, based in Iceland, for the kill of Fraatz’s U-529, In the postwar analysis, it withdrew the credit and speculated that the loss was probably due to an “accident.” According to the war diary of U-boat Control, U-529 was probably at or close to the place where the aircraft claimed a kill that day. Wartime credit for the kill of U-225 (nearby U-529) was certainly wrongly attributed. In the postwar revision, the Admiralty credited the kill of U-225 to a B-24 of Squadron 120, piloted by Reginald T. F. Turner, who was escorting Slow Convoy 119.

* Initially the Admiralty attributed the loss of U-623to “unknown causes,” date also unknown. Much later in the postwar analysis, British historians concluded that Isted did the deed.

† As related, in the postwar analysis, the Admiralty Withdrew credit for the kill of U-225 from Spencer and gave it to pilot Turner in a B-24 of British Squaclron 120.

* The damage that Campbell incurred in her unintentional ramming of U-606 precluded any hope of her putting over a boarding party.

* Several days later during a howling gale, Manhardt von Mannstein in U-753 found a crowded Madoera lifeboat. He ordered six white men to U-753 but left “a number” of black Lascars in the boat. Upon learning of this episode, British propagandists branded Manhardt von Mannstein an “atrocity monger.” Hans-Jurgen Zetzsche in U-591 found and captured Madoera’s first mate in another lifeboat, leaving the other survivors to their fate, but he was not publicly branded.

* Mengersen’s confirmed score on the duck U-18, and the VIIs U-101 and U-607 was sixteen ships for 84,961 tons.

† Dahlhaus, crew of 1938, had served as a watch officer for eighteen months on the VII U-753, commanded by Manhardt von Mannstein.

* The three losses in Halifax 224 in February are counted in the January figures. See Appendix 3.

* See Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

† In addition, nine escorts were lost, all of them to U-boats inside the Mediterranean in the last third of 1943.

‡ Three, U-105, U-123, and U-515, embarked for West Africa but were temporarily diverted to the Gibraltar-Azores area.

* Many published works credit the American submarine Herring with the kill of U-163, but after a meticulous reappraisal, Admiralty historians credit Prescott.

* Before resailing, Günther Seibicke in U-436, who sank two tankers in convoy TM 1, was awarded a Ritterkreuz on March 27. At that time his confirmed score was five ships for 33,091 tons, plus damage to two other tankers in the North Atlantic. On the same day, Drumbeater Ulrich Folkers in U-125, who had sunk no ships on this patrol nor contributed to the chase of TM 1 or other Torch convoys, also received a Ritterkreuz. At the time of the award his confirmed score was sixteen ships for 78,136 tons.

* See Appendix 15.

* Kurt revealed that he was on Doggerbank in Yokohama harbor on November 30, 1942, when the German tanker/supply ship Uckermark blew up, destroying the German raider Thor and the German supply ship Leuthen, and damaging several other Axis vessels. He confused the names of the German ships that were lost in the explosion and fire, but his information helped Allied intelligence sort out that disaster and puzzle out which German ships were probably left to raid in the Far East or Indian Ocean or to run the blockade into France.

* At the time of the award, his score was sixteen confirmed ships sunk for 86,500 tons. Normally Type VIIs did not carry doctors. Perhaps U-590 was to transfer the doctor to a U-tanker (U-460 or U-462) on the North Atlantic run.

* Under Kals and Keller, U-130 sank twenty-five confirmed ships for 167,350 tons to rank twelfth among all U-boats in the war. See Appendix 17.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score on U-563 and U-521 was six ships for 23,613 tons, including the damaged hulk Molly Pitcher.

* To extend the Allied convoy coverage farther southward, the U.S. Navy created a base for flying boats at Agadir, in southern Morocco. On April 17, six Catalinas of Squadron VP 73 transferred to Agadir.

† In January 1952, salvors refloated U-167, towed her into Las Palmas, and scrapped her.

* The six VIIs of Brazil-bound group Delphin, two IXs bound for the Americas, and two IXs of group Seehund bound for Cape Town.

* TM 1, UC 1, XK 2, KMS 10, UGS 6, RS 3.

† Originally christened the Uluc Ali Reis, she was one of four submarines built in Great Britain for Turkey in 1940. Two boats went to Turkey (a gesture to entice her into the war on the side of the Allies), but the British retained the other two, rechristened P-614 and P-615.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was twenty ships for 130,133 tons.

† After U-48, U-99, and U-123, the U-124 was the fourth most successful U-boat of the war. Under command of Georg-Wilhelm Schulz and Mohr, she sank forty-eight confirmed ships for 224,000 tons, including two warships: the British cruiser Dunedin and the French corvette Mimose. Credited with sinking twenty-nine confirmed ships for 135,000 tons, including both of the warships, Mohr stood nineteenth among all skippers in the war.

* See Appendix 7.

† There were two types of FATs: FAT I, which made a long and a short loop, and FAT II, which made a long loop and then a circle.

* At the time of the award, Brandi claimed fifteen ships, including a destroyer, for 58,700 tons sunk, plus six ships damaged for 61,500 tons. The confirmed score was seven freighters (no destroyer) sunk for 22,100 tons.

† At the time of the award, Brandi’s claims were nineteen ships sunk for about 80,000 tons, including two cruisers and a fleet destroyer, plus nine ships damaged for about 88,500 tons, including a battleship, a big troopship, a cruiser, and three destroyers. His confirmed score was ten ships sunk for 29,339 tons, including one warship, the 2,650-ton British minelayer/cruiser Welshman.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score in the Atlantic and Mediterranean was four ships for 27,326 tons, plus damages.

† On March 19, Mediterranean skipper Baron Egon-Reiner von Schlippenbach in U-453 was awarded a Ritterkreuz. His confirmed score was two ships for 10,061 tons plus damage to the 9,700-ton British hospital ship Somersetshire, which the Germans classified as a troopship.

* $ At the time of the award, his confirmed score was four ships for 12,887 tons, including the British destroyer Partridge, shared credit with the Luftwaffe for an American Liberty ship, plus damage to two other large vessels for 26,686 tons, one a troopship, Cameronia.

* During the same period, the Allies sank eight Italian submarines in the Mediterranean (Nar-valo, Santorre Santarosa, Tritone, Avorio, Malachite, Asteria, Mocenigo, Gorgo). The Canadian corvettes Port Arthur and Regina each sank one, as did the new American destroyer Nields and the Dutch submarine Dolfyn. An Army Air Forces raid on Sardinia got one. British surface ships and aircraft got three. A ninth submarine, Delfino, was lost in a collision off Sicily.

† On February 6, Luftwaffe aircraft torpedoed and sank the Canadian corvette Louisburg, one of fifteen such vessels escorting convoy KMS 8, en route from Gibraltar to Bone. The British destroyer Lookout rescued forty men; thirty-eight were lost.

* A full description of these books or of the "small wireless set" has not been published. Enigma historian Ralph Erskine says that bigram tables Stmm were recovered "but no other captures of consequence.” For a description of how these tables were used, see his article, "Naval Enigma: The Missing Link.…”

† The Admiralty has not revealed whether or not it attempted to refloat U-205 or to further search the wreck for other valuables, such as FAT and homing torpedoes or those fitted with the new Pi2 magnetic pistols.

* Heine returned to France to command a new VII.

* Twelve boats times forty-seven crew, less sixty-five men: Forty-five from U-205, U-224, and U-301 were captured and twenty rescued by Axis forces or neutral Spain and returned to Germany.

* At the time of the award, Neitzel’s confirmed score was five ships sunk for about 28,400 tons and seven ships damaged for about 42,000 tons.

* In the first quarter of 1943, the Axis sailed ten blockade-runners from the Far East to Europe. Four were recalled to Japan for various reasons but six proceeded. Of these, five were lost: Hohenfried-burg (sunk by Sussex), Doggerbank (by U-43), Karin (by Savannah), Regensburg (by Glasgow), Irene (by Adventure). Although damaged, the sixth ship, Pietro Orseolo, reached Bordeaux on April 1. In the same quarter, four blockade-runners sailed from Europe to the Far East. Himalaya aborted; Portland was lost (to Georges Ley gues), Osorno and Alsterufer reached Japan on June 4 and June 19, respectively. In summary, of the fourteen sailings, only three vessels reached their destinations.

* See Appendix 11. On April 1, 1943, there were ip Newfoundland and Nova Scotia eight frontline ASW squadrons of American and Canadian aircraft, comprising over one hundred B-24 Liberators, Cansos, Catalinas, plus two U.S. Navy squadrons of PV-1, Venturas, and five RCAF squadrons of Hud-sons and Digbys.

* Achilles in U-161 and Grandefeld in U-l 74 were not far from Nova Scotia on April 26, perhaps with collateral duty to provide backup for U-262. That backup evaporated on April 26 when, as related, Achilles found a convoy and, perhaps in pursuit of same, U-l74 was sunk on April 27.

† Plus the Italian submarine Cagni and the Americas-bound IXC U-161.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was twenty-four ships sunk for 143,920 tons, plus damage to five others.

† Credited with sinking twenty-six confirmed ships for 156,000 tons, Lassen ranked twelfth among all skippers in the war.

* At the time of the award, his score was sixteen confirmed ships sunk for 86,911 tons. ASW forces in South African waters had been reinforced to thirty ASW trawlers, eighteen of them released from duty on the U.S. East Coast.

* Clausen was credited with sinking twenty-three confirmed ships for about 75,000 tons on U-37, U-129, and U-182. Ten of the ships displaced less than 2,000 tons. Had they been as large as claimed, he would have ranked high among all skippers.

† The big Italian submarine Da Vinci, with eight 21” torpedo tubes and two 4.1” deck guns, sailed independently to Cape Town on February 20, under command of Gianfranco Gazzana-Priaroggia. She sank six ships for 58,973 tons, including the 21,517-ton British troopship Empress of Canada, earning Gazzana-Priaroggia high Italian awards and a Ritterkreuz. On May 23, as she was entering the Bay of Biscay, Da Vinci was sunk by the British destroyer Active and the British frigate Ness with the loss of all hands.

* The huge 1-30, commanded by Shinobu Endo, left Japan on April 4, 1942, patrolled in the Indian Ocean, replenished from an armed merchant cruiser, then reached Lorient on August 5, where she was greeted with great fanfare by Admiral Raeder and other high naval officers. In compliance with a prior request from Berlin, she delivered 3,300 pounds (1,500 kilograms) of mica and 1,452 pounds (660 kilograms) of shellac. She departed Lorient on August 22 with a valuable load of German naval equipment: a submarine torpedo fire-control system (or data computer), five G7a (air) and three G7e (electric) torpedoes, 240 rounds of the sonar deflector Bolde, a search radar, a Metox, a hydrophone array, fifty Enigma machines, and other gear. The h30 reached Singapore on the morning of October 13 and after only six and one-half hours, resailed (to Japan. Outbound from Singapore, she hit a Japanese defensive mine and sank with the loss of fourteen of her 110 men. Later the Japanese salvaged some German gear from the wreck.

* After she was repaired, Dasher, anchored in the Firth of Clyde, blew up on March 27 and sank with the loss of 378 men. The Admiralty blamed the accident on a faulty aviation-gasoline system and, to minimize accidents, insisted that other American-built “jeep” carriers for the Royal Navy be modified, triggering another Anglo-American naval controversy.

† For these and past victories and claims, Reche was awarded a Ritterkreuz, the second skipper in the Arctic force after Siegfried Strelow to be so honored. At the time of the award, Reche’s score was ten confirmed ships sunk for 53,519 tons.

* Conceived in prewar years as passenger planes, they were then under consideration for bombing the United States by refueling from U-boats.

* See Appendix 6.

† Riccardi had replaced Domenico Cavagnari on December 11, 1940, and remained in that post until Italy capitulated. His formal jaw-breaking title was Capo di Stato Maggiore delta Marina e Sot-tosegretario di Stato alia Marina.

* Four 1,700-ton Italian “U-ciruisers” were built and named for Italian admirals: Cagni, Caracci-olo, Millo, and Saint Bon. They were armed with eight torpedo tubes forward and six aft and carried a normal load of thirty-six 18” torpedoes. All but Cagni were sunk by Allied forces in the Mediterranean in 1941 and 1942 while on cargo runs between Italy and North Africa.

† The ten VIICs designated for transfer to the Italians were U-428 to U-430, U-746 to U-750, and U-1161 and U-1162, all to be commissioned in the summer of 1943 and named S-l to S-10. Owing to the collapse of Italy, none was ever transferred to Italy; all became German school boats.

‡ X The Type XX was never built.

§ Archimede, Da Vinci, Tazzoli, Giuliani, Cappellini, Torelli, Barbarigo, Bagnolini, and Finzi.

* The Japanese renamed the boat RO-500.

† After two weeks of intense training at Tobermory, the three Canadian MOEF escort groups got actual combat operational training by joining the British escort groups (37, 38, 39, 40) guarding Torch convoys between the British Isles and the Mediterranean (KMF, KMS, MKF, MKS). The original sixteen Canadian corvettes assigned to Torch duties were formed into three Canadian escort groups (CEG 25, 26, and 27) and also joined British escorts protecting Torch convoys. Axis forces sank two of the sixteen Canadian corvettes, Louisburg and Weyburn. Another, Lunenburg, remained in the British Isles until August for overhaul and upgrading.

* Not counting XB minelayers, XIV U-tankers, and IXD 1 and IXD 2 U-cruisers, but counting all VIIs and IXs in France undergoing battle-damage repairs, modification, or refits, however extensive.

† Note well that, in the crucial year, September 1, 1942, to September 1, 1943, the Atlantic force shrank from 124 U-Boats to 123. Compare Plate 1.

* In the month of February 1943, there were another thirty-one collisions (involving sixty-two ships) in New York harbor, including the U.S. Navy fleet destroyers Come and Tillman. In the early dark hours of April 1, convoys Halifax 232 and UGS 7 departed three hours apart in heavy fog and became intermingled. Six collisions occurred; fourteen other ships did not sail or aborted, reducing Halifax 232 by sixteen ships and UGS 7 by ten ships, serious setbacks.

* The Iceland shuttle consisted of eight American warships: four destroyers, three Coast Guard cutters, and one minesweeper. Coast Guard cutters would continue to man the Greenland Patrol and escort supply ships from Canada to American bases in Greenland.

† In the period September 19, 1942, to March 20, 1943, twenty Slow Convoys, comprised of 1,184 merchant ships, sailed from New York.

‡ X The old Witherington and ten old ex-American Town-c\d&s, These destroyers were in “relatively poor shape,” Task Force 24 reported to Atlantic Fleet commander Royal Ingersoll. Two were in extended overhaul; four in refit but to be available between March 2-22; one scheduled for refit beginning March 10; and only four in operation, one of which {Leamington) was unsuitable for open-ocean sailing due to her very limited endurance. In addition, the Canadians still had seven old ex-American Town-class destroyers that they had received directly from the U.S. Navy. (See Volume I, appendices 9 and 10.)

* See Appendix 11.

† See Appendix 5.

* From its 1943 allotment of B-24s, the RAF gave the RCAF five a month in April, May, and June.

* Fulfilling wartime contracts, Martin produced 1,312 Mariners.

† Squadrons VB 125 and VB 126 (formerly VP 82 and VP 93) arrived in Canada on March 1, 1943, and rotated back to the United States on June 18, 1943. Squadron VB 127 relieved Catalina Squadron VP 92 in Morocco on September 6, 1943; VB 128 relieved Catalina Squadrin VP 84 in Iceland on September 5, 1943.

‡ $ Including one from the Arctic, U-592.

* The first of a new series of fourteen U-tankers, U-487 to U-500, of which only four, U-487, U-488, U-489, and U-490, were completed and reached the Atlantic.

* Astonishingly, over a month later, on April 5, the homebound U-336, commanded by Hans Hunger, picked up six other survivors of the Jonathan Sturges and took them to France. This act of humanity was apparently overlooked and therefore not introduced in the Dönitz trial.

* See Appendix 3.

* At the time of the award his confirmed score was ten ships for 60,157 tons, all sunk on the North Atlantic run, plus damage to an American Liberty ship. It was a success that almost exactly duplicated that of Siegfried Forstner in U-402, who sank ten and one-half ships for 57,000 tons during that difficult winter to win a Ritterkreuz.

* A “romper,” as opposed to a “straggler,” was a vessel that violated orders and left its assigned convoy and proceeded ahead all alone.

* At the time, the kill was credited to a Leigh Light-equipped Wellington, but in a postwar reassessment, the Admiralty credited the Whitley.

* The British calculated that in the fifty-four sorties, British aircraft sighted thirty-two U-boats and conducted twenty-one attacks.

* Control logged that Beaufighters were “superior” to the JU-88 Model 6C. The German planes were too slow, underarmed, and had water-cooled engines that were vulnerable to enemy fire.

* Figures as compiled by Professor Rohwer. Berlin propagandists claimed that Axis forces sank one million gross tons of shipping in March, bringing the claims for the war to thirty million gross tons. The actual figure for the war was about eighteen million gross tons. A Senate investigating committee, chaired by Harry S. Truman, imprudently seemed to confirm the outlandish claims of German propagandists, reporting that Axis forces sank an average one million tons per month in 1942, or twelve million tons that year alone.

* One ship of the eastbound Halifax 227 that sailed in February was lost to U-boats. None of the eight westbound convoys, comprised of 450 ships, sailing in March lost a ship to U-boats. One ship from Outbound North (Slow) 168 and two ships from Outbound North 169 that sailed in February were lost to U-boats. See Appendix 3.

* Enclose II, from April 6 to April 13; and thereafter Derange, see Plate 6.

* The Admiralty originally credited a Sunderland of RAAF Squadron 461 for this kill.

* However, the Admiralty erroneously credited a Sunderland of Australian Squadron 10 for the kill of U-109, later corrected in a postwar analysis.

* The Admiralty wrongly credited the kill of U-635 to the frigate Toy of Gretton’s Escort Group B-7, which had attacked a U-boat. Long after the war, the Admiralty shifted the credit to Hatherly’s B-24.

† Doubtless by coincidence, on April 7, at the conclusion of this battle, Hitler awarded Dönitz Oak Leaves to his Ritterkreuz.

* In early April, similar reports of flak-gun successes had come from three other IXs: Emmer-mann in U-172 and Helmut Pich in U-168, both IXC40s, and Karl Neitzel in the IXC U-510.

* At the time of the award, Möhlmann had commanded U-571 at the battlefronts for almost two full years. His confirmed score was six ships (one tanker) for 37,346 tons sunk, two ships (one tanker) for 13,658 tons wrecked beyond repair, eight ships for about 51,000 tons destroyed plus damage to another tanker of 11,400 tons. Upon arrival in France, he left the boat for other duties and later was appointed commander of Training Flotilla 14.

* See photo opposite p. 497, Volume I.

† Control logged further that this unusual Italian report was “confirmed” by B-dienst on April 13.

* In three prior Atlantic patrols, Horst Hessler in U-704 had sunk only one confirmed ship, a 4,200-ton British freighter. It is not clear why the boat was retired so soon. After reaching the Baltic.in early April, Hessler was reassigned to commission a new VII.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was fifteen ships for 77,483 tons, including the British destroyer Veteran. The hits on Biter could not be confirmed.

* In a 1991 reassessment, the Admiralty credited the British destroyer Vidette of B-7, commanded by Raymond Hart, with the kill of U-630

* Halifax 231 to 235; Slow Convoys 125 to 128; Outbound North 176 to 181; Outbound North (Slow) 3 to 5. See Appendix 3.

† According to Admiralty figures. In a close match, Professor Rohwer has calculated fifty-five merchant ships lost in April for 312,612 tons.

* In his book Iron Coffins.

† Hitler’s gift to Tojo, the IXC U-511 (“Marco Polo I”), sailed to Japan on May 10, but separately. Her skipper, Fritz Schneewind, sank the 7,200-ton American Liberty ship Sebastiano Cermeno

* Since April 12, 1940, on U-37.

* On November 7, 1941.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score was thirty-eight ships sunk for 189,633 tons, second in (confirmed) ships and tonnage after Kretschmer.

* At the time of the award, his confirmed score on the VII U-98 and U-l 77 was twenty ships for about 116,000 tons.

* Having sunk twenty-four confirmed ships for about 140,000 tons on the VII U-98 and U-177, Gysae ranked seventeenth among all skippers in the war.

* Hitler’s gift to Japan, the IXC U-511 (“Marco Polo I”), and the Italian cargo submarines Cappellini and Giuliani had reached Penang in July with spare torpedoes for the returning German U-cruisers.

* At the time of the award, Lüth’s score on the ducks U-9 and U-138 and the IXs U-43 and U-181 was forty-seven ships sunk for about 229,000 tons, including the French submarine Doris. He was the second-ranking U-boat skipper in the war after Otto Kretschmer who, as related, sank forty-five ships for about 270,000 tons and captured one for about 2,000 tons.

* The crew of U-181 received high, decorations as well. The chief engineer, Carl-August Land-fehrmann, was awarded a Ritterkreuz, the seventh presented to U-boat engineers to that time.

* There were five thousand German POWs on board, including some submariners, en route to camps in North America, confined to the lower deck under guard.

† This elusive objective was finally attained in October 1943, by the far-fetched “recognition” of an ancient Anglo-Portuguese treaty. American reinforcements soon eased into the Azores under British flag. In 1944, the Portuguese allowed the Americans to openly build air and naval bases on the island of Terceira.

* As related, Herring sank the 7,000-too Vichy freighter Ville du Havre during the Torch invasion. The Shad damaged the inbound blockade-runner Pietro Orselo on April 1.

† See U-boat Control (BdU) War Diary (KTB) on those dates and at NARA in RG 457: SRMN 35, p. 45; SRMN 37, pp. 58-137; SRH 208, pp. 70-93.

* Partly an inside joke: Walter’s young son was named Ingol.

* The XVIIAs U-792, U-793, U-794, and U-795 and the XVIIBs U-1405, U-1406, and U-1407.

* Ordinarily the snort was raised and laid down flat into a slot on the upper deck almost effortlessly by hydraulic devices. In this instance the hydraulic system must have malfunctioned.

* The FAT II (electric) was to be introduced first in the Mediterranean and Arctic, where the FAT I (air) could not be used owing to phosphorescent water in the former and too much daylight in the latter. If all went well, FAT IIs were to be issued to the Atlantic U-boat force in May. The production rate was modest: one hundred torpedoes per month to start, gradually increasing after August 1943.

* The others: U-211, U-256, U-263, U-271, U-650, and U-953. Four first sailed in October 1943. The U-263 and U-650 did not ever sail as flak boats.

† Including U-636, which made her maiden patrol in the Atlantic but was transferred to the Arctic at its conclusion, and two boats that sailed for the Mediterranean, U-409 and U-594. The U-409 got into the Mediterranean, but a Hudson of British Squadron 48, piloted by H. C. Bailey, sank with rockets the U-594, commanded by Friedrich Mumm, on June 4.

* Including three transfers from the Arctic, U-467, U-646, and U-657. The usual setbacks and delays in the Baltic continued. An Eighth Air Force raid (126 bombers) on Kiel on May 14 sank at dockside the VIIs U-235, U-236, and U-237 and damaged the VIIs U-244 and U-1051, two VIIF trans-’ port boats, U-1061 and U-1062, and the XB minelayer U-234. Another Eighth Air Force raid (ninety-seven bombers) on Vegesack (Bremen), on May 18, severely damaged U-287 and U-295. The VII U-450, which had been rammed at a Kiel dock in the fall of 1942, was rammed a second time near Danzig during workup. The IXC40 U-528 twice collided with other boats in tactical exercises. Found wanting for various reasons, her original skipper and that of the VII U-671 had to be replaced.

† See second footnote, p. 170.

‡ Type IXs going to calmer Middle Atlantic waters or to more remote areas carried twenty torpedoes, six of them G7as, in topside canisters. The fourteen belowdecks consisted of six T-3s and four conventional G7es in the bow and two FAT II and two conventional G7es in the stern.

* The Admiralty originally attributed the kill of U-663 to a Halifax of British Squadron 58, but Alex Niestlé (1998) credits Rossiter.

† Submarines Versus U-boats (1986).

* The attribution of these kills is derived from Franks, Search, Find and Kill (1995), a revision of his edition of 1990. At this time, Oulton also sank an inbound VII, as will be described.

* Deliveries of B-24s to the U.S. Navy commenced in August 1942. That year the Navy received fifty-two new B-24s; in 1943 it received 308 new B-24s and in 1944, 604 new B-24s.

† See Volume I, pp. 478-479. MAD stood for Magnetic Airborne Detector. Employed by low-flying aircraft, the gear could detect magnetic anomalies made by a submerged U-boat.

* The Army Air Forces transferred 217 ASW aircraft to the U.S. Navy: 77 B-24s, 140 B-17s, B-18s,andB-25s.

† One pilot in VB 110 was Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., eldest son of former Ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy and bRöther of the future President of the United States, John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

‡ Contrarily, the official USAAF historians wrote that in the period July 13-August 2, American Squadrons 4 and 19 of 479th Group played “an extremely active part” in the Biscay campaign. The Americans sighted twelve U-boats, attacked eight, sank one, U-404, and shared credit with the RAF and RCAF for sinking U-558 and U-706. Five B-24s were lost, one to U-boat flak. Thirty-seven airmen perished.

* In the previously cited NSA document NR 1736, Box 705, RG 457, “Bombe History,” signed by Wenger, Engstrom, and Meader.

† The misleadingly titled Information and Secrecy (1994). The unreleased documents are cited under the general rubric “NSA RAM File.” RAM is an acronym for Rapid Analytical Machines. Of course, Burke also relies on many NSA documents that have been released to NARA (RG 457) as well as an impressive list of other documents and published works.

* Benignly known as Communications Supplementary Activities Washington (CSAW, pronounced “See-Saw”) and later, the Naval Security Station.

† The official British intelligence historian wrote that “the earliest British four-wheel Bombes proved to have low serviceability, owing to the shortage of good quality raw materials.” See Hinsley, vol.2(1981),p.752n.

‡ See Appendix 3.

* At the time, the Admiralty erroneously credited a B-24 of Squadron 86 with this kill. Including his role in sinking U-563, this was Oulton’s second kill in May.

* His score in the Arctic and Atlantic was five confirmed ships (two tankers) sunk for about 54,000 tons; mortal damage to the 11,500-ton British cruiser Edinburgh; damage to a 7,200-ton British Liberty, Fort Concord, finished off by U-403.

† Account according to Franks (1995), reconfirmed by Niestlé. Originally the Admiralty listed the cause of the loss of U-753 as “unknown.”

‡ See Appendix 2.

* Sunk were U-89, U-186, U-456, U-753, and the Elbe boat U-266, which, as related, had pulled out to refuel. There were no survivors from any of the lost U-boats. The U-223 and U-402 were among the most heavily damaged.

* At the time, the Admiralty erroneously credited Swale with sinking U-640 and another American Catalina of VP 84 with sinking U-657. In several postwar reappraisals, the credits were finally established as written. See Franks (1995), Milford (1997), and Niestlé” (1998).

* At first Allied authorities believed that in this attack Stoves sank U-954, commanded by Odo Loewe, age twenty-eight, on which Peter Dönitz was serving. There were no survivors. However, in postwar years the Admiralty credited the kill to two British warships of Brewer’s Support Group 1: frigate Jed (R. C. Freaker) and the ex-American Coast Guard cutter Sennen (F. H. Thornton).

* The Admiralty believed the U-boat was U-209, which actually was sunk earlier (May 7) by an aircraft during the battle with Outbound North (Slow) 5. In the postwar reappraisal, the Admiralty did not withdraw the credit for the kill from Jed and Sennen but changed U-209 to an “unknown” U-boat, in reality U-954.

* The Archer group had come across to Newfoundland in mid-May, escorting alternately Outbound North (Slow) 6 (thirty-one merchant ships) and the fast Outbound North 182 (fifty-six merchant ships) without the loss of a single vessel.

† Designed originally as an antitank weapon but hurriedly adapted for ASW aircraft.