The question of whether William James’ melancholy, in the months after Minnie Temple’s death, became so severe that he was obliged to take refuge at the McLean Asylum—a nearby private, exclusive, even legendary sanctuary for the “insane”—is one that still cannot be answered with certainty. There is a suggestive gap in James’ written output between August and November of 1870—no letters, no journal entries. The family has never commented definitively on the matter. The McLean has steadfastly declined to release any records or other information, regarding all such matters as confidential in perpetuity. Historian Robert J. Richards recorded that he “spoke with someone who had worked in the hospital archives in an official capacity, and she confirmed James’ stay as a patient at McLean.”1 Journalist Alex Beam reported that “several doctors and even a former director of the hospital have assured me not only that James stayed at the hospital more than once, but that they saw his name on the patient record list.”2 There are other William Jameses, however, including the psychologist-philosopher’s son, who also went through a period of depression, so there may have been a misidentification here. Even if James was a patient at the McLean, he may well have been admitted under a pseudonym. Beam says that historian Linda Simon was allowed to examine anonymous intake logs for 1870–71, and that she found no one matching William James’ general characteristics.3 The prominent historian of psychoanalysis Paul Roazen said in print that James was there,4 but he told Beam that he was there near the end of his life, not in 1870.5 James’ only surviving grandson, Michael James, has attempted to free the case file, but has been unable to satisfy the McLean’s requirement that all surviving relatives agree in writing.6 In short, it seems not improbable that James spent a short stay at the McLean at the end of 1870, but there is no direct evidence of it.

James spent much of 1871 out of view. Letters were sparse: two to Henry Bowditch, then studying under some of Europe’s greatest scientists—Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard, Carl Ludwig—one in February, and another in April.7 That same month, Charles Eliot offered Bowditch an assistant professorship in physiology at the Harvard Medical School. In June, Bowditch tried to light a bit of a fire under his perennially despondent but talented friend, writing to James from Leipzig that he expected James to join the laboratory he would be setting up at Harvard in the fall.8 If there was a reply, it hasn’t survived. The next extant letter from James dates from August to his brother Bob, then in Milwaukee. After that, nothing surviving until May of 1872. By then, his journal entries had begun again. As always, he read voraciously. Even his bad back, his poor eyes, and his dark mood did not interfere with his massive reading program: novels, plays, travel books especially by naturalists, Indian religious texts, even Swedenborg.

We know from others that in the winter of 1871–72, James joined an off-campus reading and discussion group that called themselves, “half-ironically, half-defiantly,” the Metaphysical Club.9 It was led by a man in his early forties, a kind of independent Cambridge scholar named Chauncey Wright. Nearly everyone considered Wright to be the smartest man in town, even though he was only intermittently connected with Harvard in any official capacity.10 Wright had graduated from Harvard in 1852 and had taken up a job as a calculator for a nautical magazine. It was said that he could squeeze a year’s worth of computations into three months, leaving him free to pursue his interests the rest of the year. One of his chief interests was running informal intellectual salons. He would invite some of the brightest people he knew (almost never members of the Harvard faculty, though many of his guests went on to be such later),11 and they would take turns both presenting and ferociously debating essays on the contentious topics of the day. Indeed, Wright’s whole being exuded controversy: he was an empiricist, a positivist, and possibly an atheist. He lived in a room he rented from a Black woman who had escaped slavery in the South. During the war, he had been involved in having her children freed and brought north. When Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species came out in 1859, Wright promptly read it and became a vocal advocate of the new theory. He wrote reviews and articles criticizing some of the leading intellectuals of the day: Harvard philosophy professor Francis Bowen and the president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) James McCosh were among his targets. His friend, Charles Eliot Norton, liked to publish Wright’s provocative pieces in his North American Review.

For the Metaphysical Club of the early 1870s, Wright chose several men who were considerably younger than himself (or perhaps they had chosen him): Charles Peirce, 32 (with whom he probably had the most in common intellectually), Oliver Wendell Holmes, 31 (the future Supreme Court Justice), and John Fiske, 30 (the prominent Spencerian whom Stanley Hall had seen speak in New York). James was also 30. Somewhat older were Francis Ellingwood Abbott, 36 (the Unitarian philosopher who would attempt to turn theology into a science), Nicholas St. John Green, 42 (a lawyer devoted to empiricism, especially to Alexander Bain). Green brought along a much younger legal colleague, Joseph Bangs Warner, 24.

Just before the Club was formed, in 1870, Wright had published a piece criticizing the view of Alfred Russel Wallace—the co-discoverer of the principle of natural selection—that random mutation and selection could not account for the development of the human mind. Wright responded:

[The] natural limitation of belief by belief, in which consists so large a part of their proper evidence, is so prominent a feature in the beliefs of the rational mind, that philosophers had failed to discover their true nature, as elementary facts, until this was pointed out by the greatest of living psychologists, Professor Alexander Bain… . [O]ur knowledges and rational beliefs result, truly and literally, from the survival of the fittest among our original and spontaneous beliefs.12

In short, the question was, for Wright, not so much how natural selection, operating at the level of biology, had produced the human brain. It was, rather, how natural selection, operating at the level of thought, produces the contents of the human mind. That is to say, Wright saw that the general process of “natural selection” is no more essentially tied to the origin of biological species than, say, the infinitesimal calculus is essentially tied to physical mechanics. Those are just the scientific contexts in which each happened to be first discovered. Once natural selection is understood as an abstract process—replication with variation, followed by selection according to “fitness”—it can be deployed as an explanatory apparatus in a wide array of scientific domains. Evolutionary psychologists of today would likely find that answer evasive, but Darwin himself saw it as being very much to the point, and cited Wright’s article in his 1871 book, The Descent of Man. Although Wright could not have known it at the time, by migrating the dynamics of natural selection from the biological realm to the psychological one, he set much of the agenda for American psychology for the next half-century.

In 1871 Wright published another article defending Darwin against an English opponent of his, St. George Mivart.13 In it, he bemoaned the widespread misunderstanding of Darwin’s theory even by his would-be advocates. Citing the widening acceptance in his day of a theory proposed by Jean Baptiste Lamarck some 70 years earlier—i.e., that offspring can inherit characteristics acquired by their parents through effort or accident—Wright complained:

It would seem, at first sight, that Mr. Darwin has won a victory, not for himself, but for Lamarck. Transmutation, it would seem, has been accepted, but Natural Selection, its explanation, is still rejected by many converts to the general theory, both on religious and scientific grounds.14

Darwin was so impressed by this article that he arranged to have it republished as a pamphlet at his own expense and circulated throughout England.

After Wright published a third article defending evolution in 1872,15 Darwin had his sons, then visiting America, seek Wright out personally. Once they had assured their father that Wright was of good character, Darwin invited Wright to his home in Downe, Kent. Upon meeting the great man, Wright slipped into what he exuberantly described as a “beatific condition.”16 But Darwin’s full aim in bringing Wright to England was not accomplished by merely a pleasant social call. He also took the opportunity to commission Wright to author an account of the evolution, by natural selection, of the human mind. Wright immediately agreed, and produced, in 1873, “The Evolution of Self-Consciousness.” In that work, perhaps Wright’s most important, he wrote:

The word evolution … misleads by suggesting a continuity in the kinds of powers and functions in living beings, that is, by suggesting transition by insensible steps from one kind to another… . The truth is, on the contrary, that according to the theory of evolution, new uses of old powers arise discontinuously both in the bodily and mental natures of the animal.17

The effect of Wright’s combative posture was to electrify the best young minds of Cambridge, Massachusetts—James, Holmes, Peirce, and the others—and to entice them to hear what they suspected they had been denied in the lecture halls of genteel Harvard. Perhaps the most lasting contribution to come from the Metaphysical Club’s deliberations was the development of the philosophical position that would come to be known as “pragmatism.” At several of the Club’s meetings, Nicholas Green invoked the definition of belief that had been put forward by Bain—A belief is just that upon which a man is prepared to act. The emphasis on action—on ideas doing work, rather than just being static mental contents—caught on with everyone in the group.

Peirce, in particular, developed it into a comprehensive theory of meaning, which he outlined in print in 1878: “Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.”18 Having a penchant for controversy no weaker than Wright’s, Peirce used, as his first example of this maxim, the dispute between Catholic and Protestant Christians over the nature of the transubstantiation. “To talk about something as having all the sensible characters of wine,” Peirce prodded, “yet being in reality blood, is senseless jargon.” He then declared it “absurd to say that thought has any meaning unrelated to its only function.” In case the point was missed, he went on: “It is foolish for Catholics and Protestants to fancy themselves in disagreement about the elements of the sacrament if they agree in regard to all their sensible effects, here or hereafter.”19 Only then, once he had commanded his conventional readers’ full attention with a case nearly certain to evoke fury, did Peirce deign to consider blander but intellectually more significant examples from science and logic.

Pragmatism would, of course, be adopted by many in the late 19th century, most notably by William James. Many of its adopters, however, some not fully comprehending Peirce’s intent, mangled and distorted his ideas to suit their own (often literary) purposes. Not being one to suffer such imprecision impassively, Peirce eventually changed the name of his position to “pragmaticism,” quipping that the new term was “ugly enough to be safe from kidnappers.”20

The Metaphysical Club did not last long. The young men whom Wright had assembled were all beginning careers and families, and the time they could afford to devote to intellectual recreations of that sort was rapidly dwindling. Holmes began the law practice that would eventually take him to a seat on the Supreme Court. Peirce moved to Washington, DC to work as a geodesist for the US Coast Survey.21 The position was secured for Peirce by his father, Benjamin, who was on the verge of retiring as the Coast Survey’s Superintendent after seven years.

Although geodesy was Peirce’s occupation, astronomy was his scientific passion, and these were exciting times for watchers of the skies. In 1874, there was a rare Transit of Venus, which would enable scientists to measure the distance of the sun from the Earth with greater accuracy than ever before. A second one was expected in 1882. In 1877, two tiny moons were discovered to be circling Mars by a US Naval Observatory professor named Asaph Hall. There was also a controversial debate over whether a planet, tentatively named “Vulcan,” might be hidden inside the orbit of Mercury.22 Peirce was young, talented, skilled, and connected—the world, it seemed, could hardly help but be his oyster.

James, by contrast, took up Bowditch’s invitation to spend time in his new physiology laboratory. He was finally getting the hands-on bench experience that he had long, though ambivalently, sought. In 1872 Jeffries Wyman decided to retire from teaching comparative anatomy at Harvard. Eliot sought a replacement and Bowditch recommended James. Somewhat tentatively, Eliot offered James an instructorship. James accepted and thereby began his long and legendary professional association with America’s paradoxically oldest and most modern college.

While James was wiling away the fall of 1872, waiting for his January course to begin, downtown Boston suffered a catastrophic fire, the most destructive in the city’s history. In all, 776 buildings spread over 65 acres of the city were destroyed. These included two of the city’s largest newspapers, The Globe and The Herald. The blaze was so large that fire departments traveled from every other state in New England except Vermont to assist. There was over $73 million in damage (over $1.3 billion in today’s terms), and it killed at least 20 people. Without doubt, it was the greatest calamity to have befallen Boston since before the Civil War.

One might have expected William James to express some alarm at the tragedy or sympathy for its victims. Yet, what he wrote, from the safe distance of his parents’ cozy Cambridge house, was “It was so snug & circumscribed an affair that one had felt no horror about it at all. Rich men suffered, but upon the community at large I should say that its effect had been rather exhilarating than otherwise.”23 It was an odd quirk of James’ personality that he could summon up colossal indignation about a calamity or injustice taking place thousands of miles away, but he sometimes seemed indifferent or even contemptuous of disasters that struck nearer to home, so long as they did not threaten him personally. In a contrast that might be funny if it were not so bizarre, the following year he published a piece in the North American Review in which he vehemently called for a million-dollar “vacation trust” to fund “a month of idleness” for working-class people,24 but he was unable to summon up much concern when their workplaces (if not homes) burned to the ground.

James’ first course as an instructor began in January of 1873. It was the second half of a course on comparative anatomy and physiology. It seems to have gone well. The simple medicine of regular work, something that had never really been required of James before, seemed to attenuate his years of emotional turmoil. He liked the work. He began to think of teaching as a possible career. At the end of term, he asked if he might teach the full course the following year. Eliot agreed. In August, however, James quailed. He told Eliot to find a substitute and he fled, once again, to Europe. There seems to have been no specific aim in sight, just escape: London, Boulogne, Paris, Florence (where his brother Henry was living), Rome, Venice. By the end of it, five months later, he longed to be back at Harvard teaching.25 He returned in March 1874 and arranged with Eliot to teach the full course the next academic year. He continued to work in Bowditch’s laboratory, and he began directing the anatomical museum that Wyman had assembled during his many years at Harvard.26

It was about this time that James began developing a serious interest in the relation between drugs and religious mysticism. In November of 1874, the Atlantic Monthly anonymously published a review authored by James of a pamphlet that had been written by an obscure self-styled philosopher named Benjamin Paul Blood.27 Blood, who was a decade older than James, lived in the upstate town of Amsterdam, and most of his writings, ranging over a variety of “grand” topics, had appeared as letters to tiny local newspapers. He was a farmer by trade, but he made his name as a local strongman who also did mathematical tricks like multiplying large numbers in his head.28 In 1860, Blood was given nitrous oxide for the first time, while in a dentist’s chair, and he came away convinced that he had experienced a great religious revelation. He continued to experiment with the curious gas and, in 1874, he composed a short tract about his experiences titled The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy.

On reading it, James became entranced with the idea that our “normal” state of consciousness is only one of many that we might assume and, more important, that certain forms of knowledge might be available to us only while in certain mental states. He began experimenting himself, publishing his own findings in 1882.29 He started up a lively correspondence with Blood, and he used his Atlantic review to ensure that Blood’s views were broadcast well beyond the boundaries of his upstate town. At the end of his long life, Blood would write a book about philosophical pluralism titled Pluriverse.30 James, of course, adopted pluralism late in his life as well, but its seeds may well have been planted here, in 1874, with an obscure pamphlet and an anonymous review.

In July 1875, James’ most important publication to date appeared in the North American Review. Like nearly all of his early pieces, it was a book review, but this time it was a description and assessment of Wilhelm Wundt’s new textbook Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie (Principles of Physiological Psychology, 1874). Wundt had won his first professorship, in Zurich, the year before and, even though his great Leipzig laboratory was still a few years off, his career as the official “founder” (if not actually the originator) of a new experimental psychology was now fully underway. Of the Germans’ new “physiological” interest in the mind, James quipped appreciatively, “there is little of the grand style about these new prism, pendulum, and galvanometer philosophers. They mean business, not chivalry.”31

James began his review by praising the new German physiologists for being able to separate their metaphysical and religious stances from their scientific investigations into psychology, unlike, he noted pointedly, James McCosh, president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), and Noah Porter, the even more religiously orthodox president of Yale. Then James cited Wundt as the “paragon” of the new breed.

The style is extremely concise, dry, and clear, and as the author is as thoroughly at home in the library as in the laboratory, the work is really a cyclopædia of reference … we can think of no book (except perhaps the Origin of Species) in the course of which the author propounds so many separate opinions.32

Comparing Wundt’s work with Helmholtz’s epoch-making measurements of the speed of neural transmission, James described Wundt’s “complication experiment”: reaction times were taken under a variety of different conditions, and the different results were compared and interpreted as reflecting the durations of the mental processes involved. There are mentions of the complexities generated by Wundt’s ultimate targets of investigation: attention, consciousness, apperception, and volition.

Then James came to a point that is emblematic of much of his career as a psychologist: Mental experience is a complex mass and is wholly personal. The “pure sensation” is not a natural element of the mind; it is an abstraction that would never enter experience unless one severely circumscribes one’s attention with the specific aim of “finding” it. As James put it:

These acts postulate interests on the part of the subject, interests which, as ends or purposes set by his emotional constitution, keep interfering with the pure flow of impressions and their association, and causing the vast majority of mere sensations to be ignored.33

Here James’ critique veered away from Wundt. Instead, he abruptly raised the psychology of Herbert Spencer, the popular “social Darwinist,” only to reject it for missing this central truth of the matter: sensations are not the natural foundations of mental activity but its artificial constructions. However, he laid the insight—one that is often attributed to James himself—at the feet of Chauncey Wright and his 1873 article, “Evolution of Self-Consciousness.”34

James then briefly returned to Wundt, lauding his suggestion that consciousness is able to “synthesize” disparate mental contents into new wholes so fully that it seems impossible analyze them back into the original parts again. He quickly assimilated the idea, however, to John Stuart Mill’s “mental chemistry,” a comparison that would become quite popular, but would also impair the English-language understanding of Wundt for decades to come.35 Finally, James posed an evolutionary question against Wundt’s accomplishment,36 a question that clearly reflected a view of the mind he had learned from Wright and which prefigured some of his own most important psychological insights in the years to come:

Taking a purely naturalistic view of the matter, it seems reasonable to suppose that, unless consciousness served some useful purpose, it would not have been superadded to life. Assuming hypothetically that this is so, there results an important problem for psycho-physicists to find out, namely, how consciousness helps an animal, how much complication of machinery may be saved in the nervous centres, for instance, if consciousness accompany their action.37

He closed with the opinion that, although the book had many “shortcomings,” it was still “indispensible for study and reference.”38

In the summer of 1875, James went to Wisconsin to visit his two youngest brothers. In September, while James was still away, Chauncey Wright suffered a stroke and died.39 James published an obituary in The Nation. Wright’s passing marked, for James, the loss of his most important philosophical mentor (apart, perhaps, from his father). Even though James did not ultimately adopt the path Wright had laid out in its entirety, the mark of the man could be seen in James’ thought for decades afterwards.

Starting in the fall of 1875, James taught the anatomy and physiology course at Harvard again. He also taught, for the first time, a small graduate seminar on physiology and psychology. Near the end of term, he proposed a new course: “Physiological Psychology.” It is not surprising that he used the phrase found in the title of Wundt’s textbook. In a letter to Eliot, James specifically cited Wundt as an example of how the field was developing—a synthesis of medical training, physiological research, and broader philosophical interests.40 It was a combination that James believed himself to exemplify. Apparently, Eliot did as well. He promoted James to assistant professor of physiology and scheduled the course for the 1876–1877 school year.

Perhaps surprisingly, though, James did not use Wundt’s book as the required text for his new course. Instead, for “practical reasons” (probably just the problem of using a German textbook in an American undergraduate course), he used Herbert Spencer’s Principles of Psychology.41 Spencer had been a published evolutionist prior to Darwin. His position was not really Darwinian, however (despite his often being called a “social Darwinist”). He drew on the Lamarckian position and on an even older tradition in which the cosmos is thought to be naturally (or perhaps supernaturally) developing, progressing even, toward some predestined endpoint.42 With the publication of Origin of Species, Spencer came to incorporate natural selection into his repertoire of evolutionary causes, but did not seem to fully grasp the import of mutations being random rather than teleological in character. The Darwinians, who were advancing the cause of natural science generally as much as that of natural selection specifically, were always uncomfortable with Spencer’s speculative and cosmic approach. They did not really regard him as a fellow scientist.

But James did not select Spencer’s book for his new course so that he could promote it. Indeed, he would privately come to call Spencer “an ignoramus as well as a charlatan.”43 Instead, he used Spencer’s ideas as a launch pad for his (and Wright’s) critique of it from a more strictly Darwinian perspective.44 Like Wright, James spoke of “spontaneous variations” arising and being selected at the level of thought, not just at the level of the physical organism. This, James believed, made room for his cherished freedom of the will within a scientific framework. Sometime in 1875 or 1876, James set up a demonstration laboratory in the Lawrence School building so that psychological phenomena that had been pioneered elsewhere by others could be repeated for the benefit of instructors and students alike.45

Also in 1876, the new Assistant Professor James acquired his first graduate student. It was Stanley Hall, just arrived from Antioch College, still trying to finance a voyage back to Germany to study with Wundt. Although the two men, Hall and James, were only two years apart in age and shared a bevy of similar interests, the circumstances of their births and upbringings could hardly have been more different. Hall was born and raised in an inland rural community; James grew up in the midst of the largest and most cosmopolitan port city in America (when his family wasn’t touring the great cities of Europe). Hall’s parents were frugal farmers of Puritan English stock, born of a tradition that stretched back nearly to the very beginning of European habitation in North America; James was born into a fabulously wealthy intellectual family whose immigration to America from Ireland had come just two generations before. Hall’s family practiced a highly conventional form of Congregationalism. James’ father, as we have seen, was a virtual renegade from his own father’s Presbyterianism and made it his life’s work to assemble an original and eccentric theological framework within which he could subsist. There was one way, however, in which Hall’s and James’ early lives were markedly similar: when the Civil War came, their fathers had each purchased for them exemptions from the draft.

Three years before, Hall had returned from Germany heavily in debt. He did not have the money for the new trip he aspired to make, either. It is possible that Hall knew William James when he arrived in the fall of 1876. Hall had published several pieces in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, but James was suspicious of the Hegelian mood there, as he was of most grand philosophical systems. James’ first article in JSP wouldn’t appear for two years yet. It is quite possible that Hall was a reader of the North American Review, in which a number of James’ reviews had appeared (though often anonymously), and it probably would not have been evident from the array of books he had reviewed just where his primary interest lay. Soon after Hall arrived, letters from both he and James appeared in The Nation, criticizing the state of philosophical education in the US. It is not clear whether this was a coordinated venture or just a lucky happenstance.46 It is certain, however, that Hall knew President Eliot. The two had briefly met the summer before, and Eliot was first cousin to the most famous man in Hall’s hometown of Ashfield, Charles Eliot Norton.

Knowing Hall’s dilemma, Eliot offered him an instructorship in English so that he could save money for his study trip to Germany. Hall noted to himself that Harvard’s current professor of philosophy, Francis Bowen, would be retiring soon, and thought that he might be able to position himself for a chance at the professorship in philosophy.47 So, Hall reluctantly agreed to the delay, and decided to take some courses at the same time, mostly from James. Soon he was registered for the PhD in philosophy that had only recently appeared in Harvard’s offerings.

Almost as soon as Hall arrived, however, his younger brother, with whom he was rooming in nearby Cambridgeport, took ill and died, at the age of just 31. After seeing his way through the family tragedy, Hall moved into rooms in Somerville, a little further away from Harvard.

The year demanded a great deal of work from Hall: in addition to teaching the same lecture to three classes each week, he had to mark twelve papers from each of 250 students. He was struck with scarlet fever near the end of the school year and attempted to resign before finishing what he regarded as a burdensome marking load. Eliot replied that he and the students could wait until he recovered. He eventually did, and completed his task, but he was not reappointed for a second year.

Teaching obligations and illness aside, during his first year at Harvard Hall wrote a piece for the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, the first article in which he put forward an original thesis of his own.48 Titled “Notes on Hegel and his Critics,” Hall engaged in a searching critique of Hegel’s ideas and arguments with respect to “pure thought,” “pure being,” (and its opposite, “nothing”), and “pure vacuous space.” The questions were important elements of the Kantian legacy in philosophy. Mostly Hall rehearsed arguments from other philosophers, but near the end of the article, he brought into focus a thesis first advanced by his German philosophical mentor Trendelenburg:

Only movement is and is not at the same point and moment … and so movement, understood in the most generic sense, common to thoughts and things, and not becoming, is what is motivated here. But motion is an original factor, of a new species. It is, even Trendeleburg admitted, the existing contradiction which formal reasoning easily proves impossible. Thus contradictions are overcome, though static logic is powerless to tell us how.49

From this highly metaphysical starting point, Hall then turned to psychology. Motion, he claimed, had been shown by the German physiologist Karl von Vierordt and the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Exner to be “the only immediate sensation … not founded on unconscious inferences of any kind.” Hall then, by way of a hasty claim that thought is nothing but the mental “counterpart” of physical movement quickly concluded that “time is the internal result, space the external condition, of movement.”50 This may seem a rather exotic and abstruse argument to modern eyes, but it is how early experimental psychology often achieved intellectual significance in the context of 19th-century scholarship: by claiming to offer solutions to long-standing, philosophical disputes that seemed irresolvable. If nothing else, physiological psychology was sometimes able to bring forth new phenomena disruptive enough to comfortable old positions that it might reorganize a field by breaking an old impasse.

That same year, 1878, Hall completed his dissertation on a related topic, The Muscular Perception of Space. Although Hall had spent a great deal of time working in Bowditch’s physiology laboratory, his dissertation was broadly conceptual, if not actually philosophical, in character. Although Bowditch was clearly involved, he was not among the official supervisors of the dissertation.51 Instead, it was signed off by James, then 36, the devoutly Christian Berkeleyan empiricist Francis Bowen, then 67, and by the venerable Unitarian theologian, Frederic Henry Hedge, then 73. One can only imagine what the two senior members of the committee made of Hall’s study, deeply informed by the new experimental physiology, considered as a species of philosophical treatise.

In what must have seemed a coup for Hall, a portion of the dissertation was published in the periodical that had been launched just two years before by Alexander Bain and his protégé, George Croom Robertson, Mind. It was the first English-language journal dedicated specifically to psychology, and Hall’s article was the first by an American to appear in it.52 In this rendering of Hall’s work, there was less of Hegel and his entourage, but more of Wundt, DuBois-Reymond, Helmholtz, etc. Speculation on pure being and pure thought was largely replaced by descriptions of the classic neuro-muscular experiments that had helped to bring physiology to the forefront of scientific investigation in the previous few decades. The conclusions reached, however, were not unfamiliar:

Muscular sense is thus absolutely unique in that the incommensurability between the form of external excitation and subjective sensation found in every other sense does not exist here. It is the motion of the limb, the muscle, the nerve-end itself, which responds by the feeling not of heat, light or sound, but of motion again. This sense is not a mere sign of some unknown Ding an sich [Kant’s noumenal “thing-in-itself”]. Movement, as perceived directly by consciousness, is not even found heterogeneous in quality when perceived indirectly by the special senses of sight and touch. No degree of subjective or objective analysis, though it may simplify and intercalate any number of forms, can change its essential character as motion.53

Muscular sense, that is, serves as the long sought-after bridge between the mind, which controls the muscles from within, and the outer, material world, which opposes and resists the muscles from without. It was a grand claim, to be sure, but giddy young sciences (and giddy young scientists) often start with the greatest unsolvable problems of the disciplines from which they have emerged, only later to fully comprehend the complexity of the phenomena they aim to explain, and the limitations that exist for the new science every bit as much as they did for the old.

Interestingly, in his autobiography Hall reduced the number of years he spent at Harvard to one, and he incorrectly recollected that he had completed his doctorate only after spending three more years in Germany.54 In fact, it was soon after completing his doctorate at Harvard in 1878 that he resumed his original plan of traveling to Germany to study the new physiology and psychology.

The 1870s were a turbulent time for America, but little of this comes through in either Hall’s or James’ personal writings of the period. In the wake of Andrew Johnson’s disastrous completion of Lincoln’s second term, the nation turned to its greatest war hero, Ulysses S. Grant, electing him president in 1868. Expectations were high that Grant would be able to salvage the situation in the South and in Washington itself. Henry Adams wrote that the populace was implicitly guided by “the parallel they felt between Grant and Washington.”55 But it was all a mirage. As inspiring an army commander as Grant might have been during the war, he was wholly unprepared for the job of presiding over a national government and a national economy. The collapse in confidence was almost immediate upon Grant’s taking office. “Grant’s [cabinet] nominations,” wrote Adams, “had the singular effect of making the hearer ashamed… . [They] betrayed his intent as plainly as they betrayed his incompetence. A great soldier might be a baby politician.”56 Corruption quickly reached new heights in both politics and business, soon followed by widespread public disappointment and disillusionment. In 1869, for instance, the notorious speculators Jay Gould and James Fisk manipulated the monetary policy of the economically-naïve Grant. Using their friendship with Grant’s brother-in-law to gain access, they persuaded the President not to sell government gold, ostensibly as a way of assisting western wheat farmers. Meanwhile, they secretly attempted to corner the market in private gold. The scheme ultimately failed, but Grant’s belated response to their plot precipitated the financial panic known as “Black Friday.” Soon after, Gould began his career as an archetypal railway “robber baron,” eventually controlling 15% of the train tracks in America.

Widespread dissatisfaction with Grant’s ability to manage the nation’s affairs led to a deep division in Republican ranks. The “Liberal Republican” party nominated Horace Greely (founder of the New York Tribune) for president in 1872.57 The Democratic Party, still in disarray in the wake of the Civil War, threw its support behind Greely as well, in a desperate attempt to take advantage of the Republican split. Matters were complicated by the fact that Greely died between voting day and the time the electors gathered to cast their ballots. It made no difference to the final outcome as Grant won the popular vote easily, out-distancing Greely by 12 percentage points. The corruption continued unabated. Grant’s Secretary of War, William W. Belknap was impeached by a unanimous vote of the House of Representatives for taking bribes. He resigned in order to avoid prosecution, but the Senate tried him anyway. The vote for conviction fell a few votes short on the strength of Senators who believed they no longer had jurisdiction once Belknap had fled office.

Despite his general administrative ineptitude, Grant was able to oversee successive victories in civil rights for freed slaves and other African Americans during his terms in office. The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, prohibiting states from denying Blacks the right to vote, was ratified in 1870. The Civil Rights Acts of 1871 protected Blacks (at least on paper) from ethnic violence, particularly at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. The Civil Rights Act of 1875 mandated equal treatment of all people by “public accommodations.” It would be struck down in 1883 by the US Supreme Court, which ruled that the constitution does not empower the state to prohibit discrimination by private individuals. The 1883 ruling paved the way for more than a half-century of “Jim Crow” laws, until the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A few months after Grant started his second term, September of 1873, the largest investment bank in the country—Jay Cooke, based in Philadelphia—declared bankruptcy and closed. Cooke had borrowed heavily to finance the Northern Pacific Railroad, but the post-war boom in track-building had already peaked back in 1871. Falling grain prices had led western farmers to demand, and win, “Granger laws” that regulated the rates rail companies could charge to ship commodities back east.58 In the face of this uncertainty, investors began to back away from the over-extended railroads. Corruption in Grant’s government made subsidies politically unpalatable, and a meeting of New York financiers brought no infusion of cash either. So, Cooke simply closed his doors, precipitating the worst economic crash the US had ever seen: the “Panic of 1873.”

Competition among the large rail companies—the Erie, the Baltimore & Ohio, the Pennsylvania, and of course Vanderbilt’s New York Central—became ferocious.59 Prevented from raising rates by the Granger laws (and by the capacity of an economically strapped populace to pay more), cutting wages became the primary means of maintaining profits. Indeed, it was not just the railroad companies that turned to this dark tactic. Many industries used the “Panic” as a pretext for cutting wages; miners, steel workers, factory workers, longshoremen, printers, and government workers were all hit. Unemployment became rampant, perhaps as high as 25% nationally. Protests of thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, were seen in most major cities. The government response was typically to send in police and militia, batons flailing. As the slump deepened, newspapers and governments alike began vilifying the victims with two new terms: “tramps” and “hoodlums.” The “tramp evil” had to be stamped out.60 The New York World newspaper declared charity itself to be an “epidemic.” One writer in The Nation suggested that free soup be prohibited. The American Social Science Association declared that “imposter paupers” were being used by labor as a weapon in the fight for “unnaturally” high wages.

Even as Herbert Spencer’s ideas were being criticized and rejected in some intellectually elite circles, like Chauncey Wright’s Metaphysical Club, his “social Darwinism” was being taken up in powerful quarters of American society. Edward L. Youmans’ magazine, Popular Science Monthly, just launched in 1872, had been created primarily to disseminate Spencer’s ideas on the western side of the Atlantic.61 For advocates of Spencer’s Social Statics, it was only right and natural that those who could not compete should be “selected out.” Those who could succeed—the Vanderbilts, the Rockefellers, and the Carnegies—would survive. Those who supported the poor were regarded, at best, as ignorant of these “scientific facts.” Some were denounced in the press and by politicians as “unfit” foreigners or, worse still, as communists. Suggestions were increasingly heard that poverty was the result of defective, hereditary traits, rather than of the economic situation.62 Even the co-founder of the State Charities Aid Association Josephine Shaw Lowell63 declared “able-bodied paupers” to be the bearers of a new kind of social disease, a moral contagion that could be spread to others if not rooted out and isolated. She prescribed hard labor at work houses until they were “educated morally and mentally.”64 The crisis was incomprehensible to most Americans because the industrial worker, the urban poor, the immigrant slum-dweller, though numerous, did not yet figure in the nation’s self-image.65

By the same token, the “organizational revolution” that was just taking hold in the industrial workplace was incomprehensible to the laborers: at the heart of movement was the gradually emerging idea that all workers are like cogs in a giant machine that only works with maximum efficiency (i.e., most profitably) when they all do their jobs in very particular ways at very particular speeds. Over the next half-century this understanding would spread from business to government to education and to nearly every other mass institution in America.66 Indeed, one might argue that this fundamental transformation in institutional structure was the single most significant aspect of the socioeconomic environment in which American psychology took root—it was the sea in which psychology swam.

The Panic of 1873 also enabled corporations to effectively dismantle the limited organized labor movement that had come into existence in the few years since the end of the war. With no laws to prevent owners from simply firing all organized workers, and a steady supply of unemployed men ready to take any job offered at nearly any wage, companies did their best to rid themselves of what they viewed as an illegitimate impediment to their power. In March 1877, for instance, the Reading Railroad announced to its employees that they must either quit the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers or lose their jobs. They proposed that those who remained behind could choose to take up a company-run life insurance policy to replace the one offered by the Brotherhood. However, they would lose all their investment should they quit or strike, and there was nothing to prevent the company from altering the terms of the policy should it so choose. In response, the Brotherhood called a strike but, using non-Brotherhood replacements, the Reading was running normally again (though operated by many dangerously inexperienced workers) by mid-summer.67

To make the price of challenging industrial ownership chillingly clear, ten coal miners in northeastern Pennsylvania were hanged in June of 1877 for being active in the shadowy group known as the “Molly Maguires.” The Mollies were an Irish secret society that was said to have infiltrated America and been responsible for killings and kidnappings of mine officials and strikebreakers over a number of years. Although there was violence in and around the mines, especially during strikes, historians have never been able to establish the actual existence of the group in America. Nevertheless, the miners were convicted largely on the testimony of a single Pinkerton officer who had been hired to break union activity in the mine by Franklin Gowen, owner of both the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad and the Philadelphia & Reading Coal and Iron Co. Many train and mine companies used so-called “police” (security guards they had hired or contracted from private companies such as Pinkerton) as spies to infiltrate and expose union activity. Gowen also personally prosecuted the case against the “Molly” miners. Whether or not the men were “Mollies”—whether or not the “Mollies” actually existed—workers all over the country were put on notice that there were no limits to what Capital would do to protect its investment.

Early in 1877, the largest rail companies then hatched a scheme that would enable them to systematically reduce wages throughout the system: they would “pool” the freight revenue among themselves, granting each company a guaranteed percentage. As each company cut wages and faced labor unrest, the other three would buoy it up by means of the pool. After the Brotherhood had been broken and “peace” restored at one company, then the next one, in turn, would cut its wages while being guaranteed a revenue stream by the pool. This would allow all of them to be victorious in their manufactured serial crises until wages were as low as ownership could get them.68 At this time, an engineer made about $1000 per year, depending on the company he worked for. Conductors, brakemen, and other trainmen made considerably less.

By July 1877, the rail workers had had enough. After B&O cut wages for the second time in a year, workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia brought all their trains to a stop. The governor sent in state militiamen, but they refused to fire on the strikers. Within days, the strike spread to B&O’s station in Cumberland, Maryland. The governor ordered two regiments of the National Guard to put down the strike, but the soldiers met ferocious resistance from the general population of Baltimore, who blocked the way to the trains that were to take them to Cumberland. Troops fired on the crowd, killing at least ten and wounding dozens of others. The recently inaugurated president, Rutherford B. Hayes, sent federal troops to Baltimore to restore order.69

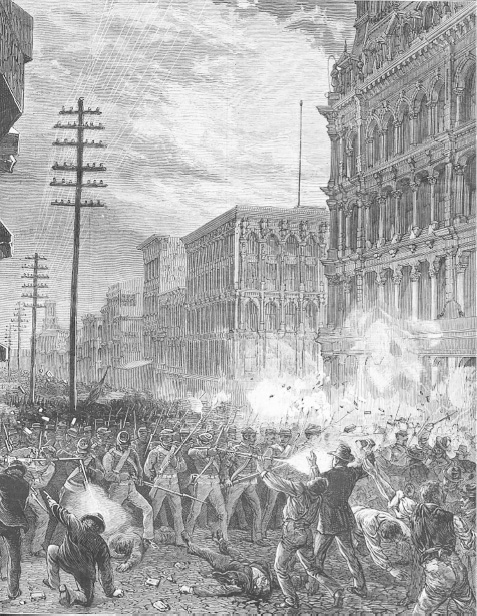

Violence then erupted in Pittsburgh where militiamen gunned down at least 20 strikers, but were forced to take refuge from the furious mob in a railway roundhouse. The strikers set the structure on fire, destroying over 100 locomotives and 1,000 rail cars. The militia killed at least 20 more people fighting their way out of the burning building. The strike spread to Philadelphia, where much of the city center was burned, then to Reading, where 16 were killed by troops. In Shamokin, Pennsylvania, the rail workers were joined by coal miners, making the events of 1877 the first de facto general strike in US history. President Hayes again sent in federal troops to put down the strike by force.

Still the unrest spread to Chicago, St. Louis, and a number of smaller cities in between. Dozens more were killed and hundreds wounded. There were strikes and other actions across New York State as well—Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Albany. Although the strikers were met by public support in many cities, they were roundly denounced by nearly everyone who had a pulpit from which to be heard. Even Henry Ward Beecher spoke out against the strike. In New York City, instead of a violent rampage, the workers staged a largely peaceful protest of 20,000. William Vanderbilt had pleaded with the mayor to ban it and, although he was officially refused, it was made known that thousands of police and troops would be on alert, and that heavy weaponry would be positioned at various important sites around the city, in case things got out of hand. As the rally ended, after two hours of speeches, police waded into the crowd without apparent provocation, beating with batons anyone who did not disperse quickly enough for their liking.70

As federal troops moved from city to city, crushing resistance, the most violent, most widespread strike in American history gradually came to an end after a month-and-a-half of massive destruction and explosive violence. Millions upon millions of dollars in damage had been done as mobs attacked and set fire to buildings and equipment related to the massive railroad industry that had come symbolize, to them, the brutal character of the new capitalist order. Some people began to opine that the labor question had now overtaken the race question in national politics. A new civil war, just twelve years after the end of the first one, now seemed a distinct possibility.

Strangely, we see nothing in James’ correspondence or in Hall’s autobiography on these portentous matters.71 Starting in September of 1876, James began intently courting a woman named Alice Howe Gibbens.72 Alice had grown up under difficult circumstances. Born in 1849, she was the oldest child of a Harvard-trained physician, Daniel Gibbens, who, like Henry James Sr., had an interest in Emanuel Swedenborg’s spiritual philosophy. Unfortunately, he was also a recurrent alcoholic whose erratic behavior interfered with the process—crucial to a physician—of amassing a steady and trusting clientele. After failing as a town doctor in the family’s home outside of Boston, he tried for a fresh start in 1855, leading his young family on a dangerous migration to distant California. After just a few years there, however, the adventure was undermined by legal conflicts over land title, and by his reversion to drink. After a humiliating return the Boston area, Alice’s father moved away from the family permanently, though he stayed in touch with his daughters by mail. During the Civil War he took up a position as an administrator for the military governor of New Orleans. His fortunes seemed to improve there, both personally and financially. He even wrote his estranged wife asking her to find a new house for the family. In 1865, however, he was unexpectedly transferred to Mobile, Alabama where things seemed to unravel. Just days before he was to head home, he committed suicide.73

In their grief and humiliation, his wife and daughters—Alice was now sixteen—moved away to Europe—Germany and Italy—for five years. They returned to Boston just in time for their small income to be slashed by the financial crash of 1873. The girls, now young adults, were forced to take jobs for income. Alice and one of her sisters took up teaching at a private girls’ school in Beacon Hill. Demanding as the work was, it had the side-benefit of bringing the Gibbenses in contact with Boston’s “Brahmins.” Alice was invited to join the prestigious “Radical Club,” where issues from the religious to the scientific were discussed by some of Boston’s best minds. It was there that she met figures such as the radical “scientific” theologian Francis Ellingwood Abbot and the Harvard physiologist who was helping James to find his footing as a Harvard instructor, Henry Bowditch. She also met, in early 1876, an older man with a strong commitment to Swedenborg, just like her own family had: none other than Henry James, Sr. According to an oft-repeated family tale, Henry went home after meeting her and announced to the family that he had met William’s future wife.74 By September of that year, William would be in earnest pursuit of Alice Gibbens’ hand.

The courtship did not prevent William from pursuing others ambitions, though. In April 1877, he wrote to Daniel Coit Gilman, the young president of a newly founded university in Baltimore, Johns Hopkins, inquiring about a position in philosophy that he had heard about from Hall.75 Unlike other American schools of the day, Hopkins was focused on original scientific research by faculty members and on graduate education. It did not even have an undergraduate college. Finding a philosopher sympathetic to that mission was proving to be something a problem for Gilman. James had recommended his old friend Charles Peirce to Gilman back in November 1875,76 but Gilman had decided to hold off on the sensitive appointment.77 Now, a year-and-a-half later, James was tiring of physiology and had told Harvard president Eliot of his desire to be considered for a philosophical post. Francis Bowen was then 66, but there was no reason for James to expect that Harvard would hire a relative philosophical neophyte like himself to replace Bowen when he retired. He thought he might have chance at Hopkins though; or, at least, that he could bring some pressure to bear on Eliot to retain him if he made a modest display of considering a move to Baltimore. By December of 1877, he had arranged to give a series of lectures the following February on “the connection of mind & body.”78 Still without any substantive publications, James offered to send Gilman book reviews as evidence of his qualification for a philosophical post. Only in 1878 did James publish his first two substantial philosophical statements in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy.79 By the end of the year he had a third article set to be published there, and another in the hands of the editor of the new English journal called Mind.80

It is interesting to observe that Henry Adams, who had just then finished his seven-year stint as Harvard’s professor of medieval history, considered the Crimson College of this era to be “fallacious from beginning to end.”81 In the chapter about this small part of his life, pointedly titled “Failure,” he opined that professors “might perhaps be frauds without knowing it,” such was their narrowness and insulation from the outside world.82 Having just fled from the corruption of Washington, DC during Grant’s presidency, Adams noted, “American society feared total wreck in the maelstrom of political and corporate administration, but it could not look for help to college dons.”83 Adams had interacted closely with both Congressmen and professors and, despite the pervasive dishonesty of the former, he said he preferred Congressmen. What was worse, Harvard was a bore: “Several score of the best-educated, most agreeable, and personally the most sociable people in America united in Cambridge,” he wrote, “to make a social desert that would have starved a polar bear… . Society was a faculty-meeting without business.”84 Among this group he explicitly named William James: they “tried their best to break out and be like other men in Cambridge or Boston, but society called them professors, and professors they had to be.”85

————

While James settled into his role as a Harvard professor, Hall continued with the plan of action that had brought him back to the east coast in the first place: returning to Germany to study physiology and the new psychology. Before he left America, however, he published a long article on the nature of color perception for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.86 He also examined the reactions of a celebrated blind and deaf woman, Laura Bridgman, who was living in an institution in South Boston at the time. The following year, the British journal that had published his thesis, Mind, also published an article of Hall’s about Bridgman.87

Money, as always, was an issue for Hall. He had saved some while at Harvard, and he also received an unexpected gift to support his travels from the banker whose children he had tutored in New York, Jesse Seligman.88 Leaving late in the summer of 1878, Hall first returned to Berlin, where he started working in the physiological laboratory of Emil Du Bois-Reymond. With the great man’s assistant, Hugo Kronecker, Hall conducted research on the electrical stimulation of muscles and the spinal cord.89 Needing to better understand electrical phenomena in order to do this work well, he took courses on the physics and mathematics of electricity. He also attended Helmholtz’s lectures on physics. While in Berlin, Hall returned to his interest in psychopathology, befriending the rising neuropathologist Paul Flechsig, whom he would meet again in Leipzig. Hall also returned to the clinic of Karl Westphal at the famous Charité Hospital in order to study living cases of insanity. As it was with James back at Harvard, mental illness was an ongoing interest of Hall’s and of many others who did not yet understand what relationship, if any, there would be between the new physiological psychology and (to use the increasingly fashionable German term of the day) psychiatry.

While in Berlin, Hall met a woman he had known back in Antioch, Cornelia Fisher. She had come to Germany to study art. Whether there had been a romance between them before is not clear, but in this place and time, a relationship quickly blossomed and the two were married in September of 1879. Indeed, Hall said that “Germany almost remade me.”90 Its more liberal attitudes toward religion, toward alcohol, toward relations between the sexes, toward the simple joy of passing a Sunday afternoon in outdoor recreations with friends, led him to discard, more fully than even in New York, many of the Puritan imperatives with which he had been raised. Indeed, he came to appreciate more fully the Seligmans, and to regard them as a sort of second, “European” family.91

In the fall of 1879, Hall traveled to Leipzig where he went to work in the physiology laboratory of Carl Ludwig.92 At first he worked on studies of reaction time with Ludwig’s assistant, Johannes Von Kries.93 Later he worked with Ludwig directly on reflexes, though the work resulted in no published articles.94 For historians of psychology, this is the time when Hall became the first American to work in the newly established laboratory of the “founder” of experimental psychology, Wilhelm Wundt. Hall, however, was disappointed with what he found there. Writing to James in February of 1880, he said that Wundt’s studies were “inexact,” that he was “sore from criticism & sneers of his fellow physiologists.” Worse still, according to Hall, Wundt was “burning with ambition to be a philosopher within a system,” and was “a man who has done more speculation & less valuable observing than any man I know who has had such a career. His experiments, which I attend, I think utterly unreliable & defective in method.”95

It is hard to know precisely what to make of these claims. Were these Hall’s observations alone? To what degree did these remarks simply echo what Hall had heard in the physiology labs of Ludwig and others? Perhaps Hall had decided to side with the physiologists, who seemed to him “more scientific,” but they had chosen the safer, more established route to scientific respectability whereas Wundt had taken the bolder step of attempting to push the boundaries of natural science outward. Also, Wundt’s professorship was in philosophy (where “psychology” traditionally had been), and physiologists may have been dismissive of him on that account alone. Tension between the established top of the academic heap, philosophy, and the rapidly expanding and increasingly prestigious natural sciences was a common dynamic in German universities of that era. This is suggested in Hall’s comment that he was himself “considered somewhat of a usurper, not entirely scientific.”96 Later in his life, Hall had mostly good things to say about Wundt: that he was “one of the most popular lecturers” at Leipzig and that he was an “indefatigable worker.” He also wrote of his “great admiration” of Wundt.97

————

James married Alice Howe Gibbens in July of 1878, after a two-year-long, tortuously complex, on-again-off-again romance. Upon news of the engagement, James’ mentally fragile sister, also named Alice, with whom he had enjoyed a close and playful relationship, fell into her most serious hysterical breakdown yet. She was nearly 30 years old, but fiercely demanded that her aging father sit by her bedside day and night for months lest she commit suicide.98 Alice, the sister, is a figure of enduring fascination to many. Some have attributed her recurrent fits of madness to the strains caused by the social and intellectual restrictions that were imposed upon talented and ambitious women in her era. Others have found in her little more than a manipulative madwoman. Clearly, periods of intense melancholy, anxiety, and loneliness weighed heavily upon her. She was not well liked by some: Lilla Cabot Perry once described her as being “clever but coldly self-absorbed.”99 She had few friends outside of the family, and she could become intensely jealous when she did not command the full attention of those few she had.100 She is known to us primarily through a diary she wrote during the last two years of her life, in which she commented sharply, with an outsider’s eye,101 on British manners and politics, as well as on the more profound vicissitudes of existence. Because her older brothers objected to its being made public, the collection of thoughts and observations was not published until 40 years after her death. There are also letters between her and her brothers. These sparse materials have spawned a much larger assemblage of books and articles from those who would have her known as an excellent, but unappreciated mind in her own right, not merely as the little sister of the illustrious Brothers James.102

Despite Alice’s alarming collapse upon hearing of her brother’s engagement, William and his new wife went to the Adirondacks for a rustic 10-week honeymoon.103 The new husband spent part of his time working on philosophy articles, to bolster his claim with President Eliot that he should be Harvard’s next professor of philosophy. In May of 1879, the Jameses had their first child, Henry III. James kept on writing and publishing.

In June of 1880, he travelled alone to Europe and visited Hall. They met in Heidelberg and spent, essentially, three whole days talking to each other. Relations between them could be strained. Although they had similar interests, they were still from different worlds. On this occasion, however, the two men seem to have gotten along well. Hall felt he was done with philosophy, that natural science was the only way forward in psychology. James, by contrast, was attempting to extricate himself from physiology and insert himself into philosophy. Both men were intellectually complex. James was no happier with traditional metaphysics than was Hall. He was just content to use the word “philosophy” for the thing he wanted to do instead. Hall, on the other hand, could not completely drop the teleology that had been so much a part of his early Hegelian training. Hall spoke of evolution, but he meant by that something closer to development—progress toward some pre-ordained endpoint—not just the hurly burly of Darwin’s random variation and selection.

Hall latched on to the evolutionary theory of the German embryologist, Ernst Haeckel. Haeckel believed that the physical development of the embryo recapitulates the evolution of the species as a whole. If, for instance, one followed the developmental trajectory of a mammalian fetus, according to Haeckel, one saw it pass through stages similar to those of microbes, fish, and reptiles, before differentiating into fully mammalian form. Hall began to think of mental development in parallel recapitulationist ways.104 The baby is a kind of mental hominin. But, as it grows, it passes through the stages of various “primitive” human types (in the view of Hall and many others of his time), gradually learning to inhibit a host of primal impulses and to develop a range of “civilized,” “adaptive” habits until it emerges as a fully-grown (White, Western) adult. Notice that this entails a pre-Darwinian view of evolution as growth-toward-a-goal, rather than just random variations being selected for or against entirely on the basis of the contingencies of a particular environment.

Toward the end of his second tour of Germany, Hall came to the conclusion that “neither psychology not philosophy would ever make bread and that the most promising line of work would be to study the applications of psychology to education.”105 Thus, before he returned to America, he took pedagogical tours of France and England. He visited the top lycées in Paris’ and a “pedagogical museum.” He consulted with Oxford and Cambridge professors, and he visited the best private schools—Eton, Harrow, Rugby—in order to be able to return to the US not only with prestigious European training in physiology and psychology, but also able to present himself as a specialist in a field that was almost wholly unknown there: pedagogy.

This not only provided Hall with a unique “calling card” on which he might be able to base a successful academic career (it combined the ineffable aura of European scholarship with the hard-headed “practical” knowledge Americans most respected). It also created some intellectual space between himself and the mentor who, as he saw it, was obstructing his way to positions either at Harvard or at Johns Hopkins. Of the many things in which James was interested, mental development and practical education did not rank high among them. Hall would always see in James a rival—a man just two years his senior who did not have as advanced a scientific education as he—but who always seemed to be regarded as the top man in the field, regardless of what Hall might do to earn a greater share of respect. And Hall did a great many things.