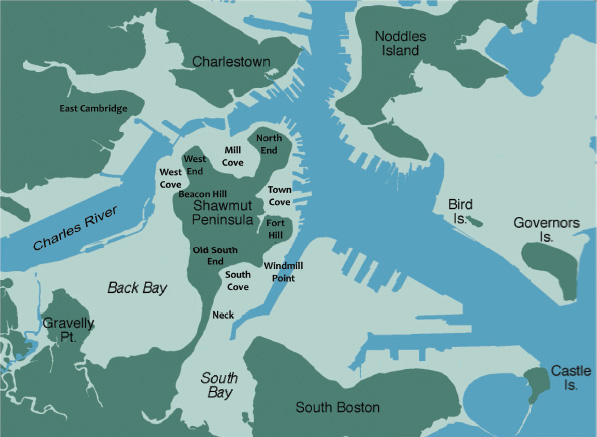

Whereas Massachusetts was established as a colony dedicated to a fierce religious monism and New York was established as a trading center not much concerned about questions of religion at all, Maryland was founded in 1634 as a colony in which English Catholics could practice their faith without the prejudice that so afflicted them in the home country. It was not, however, established to be exclusively Catholic, a mirror image of Massachusetts. It was created as a place of religious tolerance extraordinary for its day. Religion was not an irrelevancy—a potential interference with trade—as in New York. Religion was very much to the point in Maryland, but tolerance of different forms of Christianity (for their toleration did not extend beyond the boundaries of Christianity) was the atmosphere they explicitly hoped to foster. In time, a government was formed in which representatives elected by the colonists occupied a “lower” house of assembly and nominees of the proprietor occupied an “upper” house.

Of course, idealistic aspirations such as these rarely work out exactly as planned, and such was the case in Maryland. The land around Chesapeake Bay that was granted by Charles I to George Calvert, Lord Baltimore and proprietor of the new colony, overlapped with land that had been already granted to the Virginia and Pennsylvania colonies, both of which were deeply hostile to Catholics. It also covered land that was already being farmed by one William Claiborne, a Virginia Protestant who had “discovered” the area years before. He refused to submit to the rule of George Calvert’s son, Cecil, 2nd Lord Baltimore,1 and, in 1635, defended his farm again Maryland authorities by force of arms. Claiborne was defeated and many of his supporters were arrested, but Claiborne himself escaped.

A decade later, in 1645, Claiborne returned at the head of an insurrection that succeeded in overthrowing Lord Baltimore and his government for a short time. Baltimore was restored to authority the following year but, by then, events in England were starting to cast a shadow that could not be ignored in the North American colonies. Parliament defeated and beheaded Charles I in 1649; Cromwell became Lord Protector of the Realm. Catholics were on the run again, even in the colonies that had been established to protect them. In 1651 a government commission was assembled to administer the colonies around Chesapeake Bay, and it was led by none other than William Claiborne. A sad echo of the English Civil War ensued which the Protestant forces won in 1655. Ten members of the Maryland’s Catholic leadership were sentenced to death. Four were actually executed. Religious tolerance was formally rescinded. At the restoration of the monarchy in England, however, Maryland was restored to Lord Baltimore and the policy of toleration was once again renewed. Then, in 1689, when William and Mary ascended to the throne, Protestants again overthrew the Maryland government. Tolerance was quashed and the colony became a royal holding until 1716 when, under George I, the colony was returned to the heir of the Baltimores, and religious tolerance was restored yet again. After nearly a century of instability, this last government of Maryland continued uninterrupted until the American Revolution.

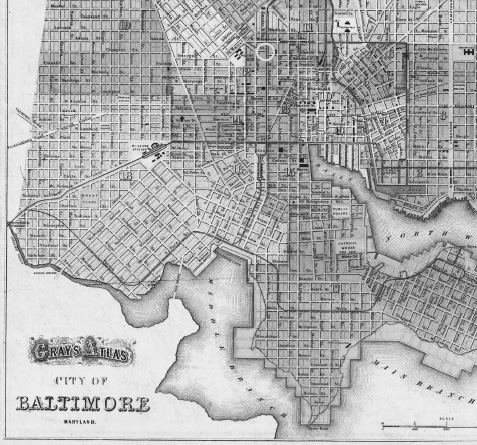

European settlement did not come to the area around what is now the city of Baltimore until the 1660s. The first church did not appear until 1692. It was not formally established as a port by the Maryland Assembly until 1706, and it was not given the official name of “Baltimore” until 1729. The town was formally incorporated in 1745. So, although Maryland became a colony at approximately the same time as Massachusetts and New York, the city of Baltimore is more than a century younger than either Boston or New York City. Around the time of the Revolution, Baltimore was known for trade in tobacco, grain, iron ore, cotton, and it soon became a ship-building hub as well. In 1845, the US founded its Naval Academy just 26 miles south of Baltimore, in the state capital of Annapolis. Being south of the Mason-Dixon line—established in 1760 to end the lingering boundary dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania—Baltimore considered itself to be the largest Southern US city. Of course, the Civil War brought new meaning to the Mason-Dixon line, and Maryland’s non-secession from the Union led to the modern convention by which authors often describe Baltimore as being politically northern but “spiritually” southern. Slavery declined in and around Baltimore after the 1810s and the city gained a reputation as a refuge of free Blacks, having a higher proportion than any other US city. It was in Baltimore that the legendary civil rights leader Frederick Douglass escaped the slavery to which he had been born in Talbot county, on the Chesapeake‘s eastern shore.

The most heroic episode in the city’s history—the moment on which much of its civic pride and identity is based—was the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. In late August 1814, the British navy sailed up the Chesapeake and the British ground troops they were carrying sacked and burned both Washington, DC and Alexandria, Virginia. They then turned their guns on Baltimore, which they believed to be a significant base of the privateers whose attacks on British merchant ships had started the war two years earlier. The capture of Baltimore would not only have likely forced the US to sue for peace. It may also have thrown into doubt American independence itself, won just 31 years before.

The ensuing battle involved a series of land and maritime engagements, during which the British were prevented from attacking the city directly. Not only was Baltimore saved from destruction but the British officer who had ordered the burning of Washington was killed by an American sniper. On the mid-September morning after the final clash at Fort McHenry, the Americans raised Mary Pickersgill’s gigantic 30–by-42-footflag, which famously inspired Francis Scott Key (a lawyer then on board a British ship to negotiate the release of prisoners) to write the poem that would later become the lyrics to the “Star Spangled Banner.” Thus was Baltimore’s position secured in the popular heroic narrative of American history.

Military glory does not fill stomachs, however, and it was not long after the British had been beaten that the city’s economic matters moved to the fore. With the opening of the Erie Canal in New York in the 1820s, eastern seaports like Baltimore were faced with the dilemma of slipping into near-irrelevance compared with Manhattan, or of devising some way of transporting goods and people cheaply into and out of the interior of the continent. In 1827, 25 Baltimore businessmen chartered a company to build a railroad to the Ohio River, from which one could navigate west to the Mississippi. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad would not only enable the city to compete with New York’s Canal; the train would actually be decidedly faster than the Erie barges. The rail line to Wheeling, Virginia (West Virginia after secession), on the Ohio River, was not completed until 1853, by which time trains were beginning to make the Erie Canal redundant even in New York, but the sections of track that opened in the intervening two-and-a-half decades were sufficient to prevent Baltimore from sinking into obscurity.

The 1830s were a harsh time in Baltimore’s history. Political tensions increased between the city, under-represented in the Maryland legislature, and the land-owning, slave-holding interests that dominated the largely rural state. Rising calls for abolition in the North, as well as the Nat Turner rebellion of 1831, led to popular violence and legal action against the Black community. Schemes to deport Maryland’s entire Black population to Liberia were seriously considered by the legislature.2 A terrible cholera epidemic in 1832 killed perhaps 1% of the city’s population. The economy steadily worsened in the run up to the Panic of 1837. Mills began to close, throwing hundreds out of work. A series of high-profiles arsons in early 1835—including the Courthouse, the Athenaeum, attempts on churches, and even an orphanage—terrorized the city’s populace. The squeeze on the poorest members of society led to the usual dreary cycle of rising labor violence and political repression.3

A massive influx of Irish and German immigrants in the late 1840s and 1850s further complicated relations between the Black and White communities in Baltimore, as it did in cities all along the eastern seaboard. During those decades Baltimore was the second-largest city in the US, ranking behind only New York. Competition for unskilled jobs was fierce. Political tension and violence soon followed in patterns we have already seen elsewhere: the rise of Know-Nothing municipal governments, the manipulation of police forces, conflict over education rights, and so forth. By the mid-1840s, however, the B&O Rail investment finally began to pay off. New factories and the jobs that railways typically bring started to spring up. Baltimore became known for the manufacture of furniture, carriages, train cars, pianos, farm tools, and for industrial baking. Its mills processed wool, and, of course, cotton, the backbone of the Southern economy. The boom of the 1840s eased tensions between the various ethnic communities of laborers. Housing construction in the city soared from 600 per year in 1845 to 2,000 per year in 1851.4 Despite the success, though, there was still civic concern that Baltimore was not growing as fast as Philadelphia and New York. By the mid-1850s, the massive purchasing by the B&O Railroad that had driven the economy over the previous few decades began to slacken after the line to Wheeling was complete. Also, Baltimore merchants were still focused on the rural South as their primary clients, and on trading commodities with Brazil. As a result, it did not experience the synergies of industrial expansion to the same extent as, say, New York. As one historian of the city put it, “Baltimore capitalists were old-fashioned… . [T]he city followed a very conservative banking policy, recirculating within a small circle.”5 Despite these anxieties, the city was more prosperous than it had ever been. The boom, naturally, busted again in 1857, its virtually customary 20-year cycle, but Baltimore recovered more rapidly than many other cities.

Everything was changed, however, by the pivotal presidential election of 1860. Marylanders voted for neither Lincoln nor Douglas, but for the southern Democrat and sitting Vice President, John C. Breckenridge, who swept the South and finished second in the electoral vote.6 As one Southern state after another seceded from the Union in the wake of the election, Maryland remained tenuously with the North and, despite sabotage by pro-Confederate bands, necessitating the imposition of martial law, Baltimore became an important Union military base during the ensuing war.

The end of the great conflict brought a wave of newly-emancipated slaves to Baltimore who were in need of work for themselves, schools for their children, and hospitals for their ill and elderly. The end of the 1860s also saw an enormous influx of German immigrants to Baltimore, rising to as high as 12,000 in 1868 alone.7 Many of the new arrivals were Catholic (fleeing Bismark’s Kulturkampf). The integration of these new ethnic communities into the city provoked, here as elsewhere, new rounds of civic conflict over jobs, housing, education, and “correct” public behavior (e.g., drinking). However, the migrants also brought with them new trades, whole new industries, and much-needed jobs. New suburbs were laid out, new mills and factories established, new schools and churches built, and new public transportation lines begun.8 An eruption of new public buildings changed the look of the downtown: a new city hall, a US courthouse, a central post office, and a palatial YMCA were built.

Still, despite the substantial post-war growth, Baltimore was gradually dropping in significance on the American scene. Other cities were growing faster and Baltimore had fallen to sixth in population by 1870.9 One of the reasons may have been that, despite their outward activity, Baltimore’s industry was not innovative. Instead, many of Baltimore’s corporations were focused on winning government decrees entitling them to:

exclusive, legally defensible rights of some kind that would ensure it a competitive advantage… . Baltimore’s businessmen were least effective in using patents. Only the canneries and a few foundries generated significant patents or technological advantages; the other industries depended on patents and machinery developed elsewhere.10

The rail companies continued to exert a tremendous influence over the city’s governance, winning for themselves concessions and favors that drained municipal coffers of much-needed cash. As a result, municipal infrastructure lagged behind that of competing cities. For instance, only a series of catastrophic floods and droughts in the late 1860s and early 1870s forced the city to finally modernize its public waterworks. In the meantime, hundreds had died of water-born disease caused by the antiquated and inadequate water system.

Despite these failings, Baltimoreans retained an enormous sense of civic pride. “If New York is to become another London… .,” declared the Sun newspaper in 1872, then “Baltimore shall become another New York.”11 There was one important amenity, however, enjoyed by the peoples of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and even St. Louis of which the denizens of Baltimore could not yet boast—a university.12 This embarrassment could not be borne much longer, so one of the city’s wealthiest men leapt in to fill the lacuna with his own personal fortune.

Johns Hopkins, a prominent Quaker abolitionist who had been a director of the B&O Railroad, passed away in 1873. At the time, Hopkins was not only one of Baltimore’s wealthiest men, but one of America’s. In his will, he made massive provision for the founding of a large number of public institutions in the city: an asylum for “colored” orphans, a university, a hospital, schools of nursing and medicine, and more. Before his death, he established Boards of Trustees to see that his plans were carried out. Just three years later, the Johns Hopkins University was founded. It was to be built entirely on interest accruing from Hopkins’ own B&O Railroad stock, a financial foundation that, in 1873, seemed as firm as any could be.

The man chosen by the university’s trustees to lead the school through its early development was Daniel Coit Gilman, a 44-year-old former Yale librarian whose stellar career as a university administrator is sometimes regarded as a key turning point in American higher education. While at Yale, he was deeply involved in the founding of the Sheffield Scientific School in 1861. In 1863 he became a professor of geography, but was called to the presidency of the University of California in 1872. Dogged by political interference on the west coast, he accepted an offer to become president of the newly established Johns Hopkins University in 1876, where he would remain for the next 25 years. It was not, perhaps, the most propitious moment to open such an institution. The following year there was another financial crash—right on “schedule,” 20 years after the last one. The crash provoked the Great Strike of 1877 (described in the previous chapter) which, it will be recalled, began in earnest in Baltimore, throwing the city, and eventually the whole country, into crisis. The crash also caused the value of the B&O stocks, on which the new university’s funding depended, to collapse. This left the Trustees with little money to develop the school, either in terms of buildings or personnel. The original plan had been to build a complete new campus uptown at Mr. Hopkins’ own estate, called Clifton, but that could no longer be achieved on the funds available. Mr. Hopkins’ will prevented the Trustees from selling the stocks themselves to exploit what capital remained, so Gilman carried on as best he could. He had the Trustees purchase buildings near downtown Baltimore, centered on one that they re-dubbed “Hopkins Hall,” at the corner of Howard St. and “Little” Ross St. (now Druid Hill Ave.)

Like Harvard’s President Eliot before him, Gilman toured Europe looking for a new model on which to base advanced education in America. Also like Eliot, he saw the centrality of science and technology to the new economy and, indeed, to the new culture. Unlike Eliot, however, rather than producing a new scheme for the undergraduate college, he envisioned a school that focused on graduate education and faculty research. It is often said that Gilman followed the German model of the university but he denied this, claiming to have taken the best of what he found at various European and American universities.13 Gilman recruited eminent and promising professors from far and wide, and the school’s novel (for the US) emphasis on research succeeded brilliantly and rapidly: in just four years, Hopkins’ faculty had published more than all other American scholars combined over the previous generation.14 Among Gilman’s “star” professors was the classicist Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve, who transformed the teaching of Latin and Greek in the US with his textbooks and who founded the American Journal of Philology. There was also the historian Herbert Baxter Adams, who founded the American Historical Association and promoted “scientific” methods in historical research. Gilman also hired economist Richard T. Ely, first Secretary of the American Economic Association and an important Progressive who advocated government intervention to curtail the abuse of workers that seemed endemic to late 19th-century industry. As well, there was the Jewish-English mathematician James Joseph Sylvester who made especially important contributions to matrix theory and combinatorics, and who founded the American Journal of Mathematics. In the natural sciences, there was the physiologist H. Newell Martin who had been a collaborator with Thomas Henry Huxley in his native England; there was physicist Henry A. Rowland who was later the first president of the American Physical Society; and there was the chemist Ira Remsen, perhaps best known for having discovered saccharin and who would go on to become Johns Hopkins’ second president.

The professorship in philosophy, however, posed a uniquely knotty problem for Gilman. On the one hand, he did not want the kind of traditional Protestant theologian who typically held such positions in American colleges. He wanted a philosopher who was in sympathy with the modern, scientific, research-oriented spirit of the institution. On the other hand, he needed to be careful to select someone who was religiously “safe,” who would not provoke conflict with the various, sometimes-fractious religious communities of the surrounding city and state. Unusual for universities of its time, Johns Hopkins had no religious affiliation, a fact that aroused more than a little apprehension in the populace, in whom conventional Christian belief was widespread and deeply felt, even if not quite mandatory. In addition to its large Protestant population, Maryland still retained a sizeable number of Catholics, descendants of the original Maryland colonists and more recent Irish and German communities. Lingering suspicion was kept from boiling over into outrage by the fact that a number of prominent Quakers and Presbyterians occupied seats on the university’s Board of Trustees, and they were among its primary benefactors. Religion was, thus, an issue that Gilman had to continuously monitor and, periodically, actively tend to.

It is not clear why Gilman had declined William James’ recommendation of Charles Sanders Peirce for the philosophy post just prior to the school’s opening. If any philosopher in America was sympathetic to science and research at that time, Peirce was. He may simply have not been accomplished enough at the time—he had published articles in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, but not yet his famous set on pragmatic philosophy in Popular Science Monthly. In addition, he was rapidly acquiring a reputation for being hard to deal with. Peirce once described himself as being “vain, snobbish, incivil, reckless, lazy, and ill-tempered.”15 As a result, he had begun to accumulate powerful enemies, not least of whom was Simon Newcomb, a former student of Peirce’s father who had risen from poverty in Nova Scotia to become a major scientific figure in the US. In 1877 he would become director of the Nautical Almanac Office at the United States Naval Observatory. Some have suggested that Newcomb was jealous of the younger and more talented Peirce; others have said that Newcomb simply despised Peirce’s imperious, dismissive attitude toward nearly everyone who did not agree with him.16 In any case, Newcomb intervened to prevent Peirce’s advancement on more than one occasion. But Newcomb was not alone; Harvard’s President Eliot disliked Peirce so intensely that he banished him from the Harvard campus. Harvard philosopher George Herbert Palmer once wrote to another university president urging him not to hire Peirce.

As we saw before, in 1877 James inquired about a philosophical position for himself at Johns Hopkins. Gilman, intrigued, invited him to give a series of lectures in 1878 on the topic of the relationship between the mind and the brain. One historian has characterized them as delivering “an extremely powerful evolutionary argument.”17 After having demonstrated his familiarity with the current state of brain physiology—and having acquainted his audience with it as well—James took on Darwin’s own “bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley, who had argued that consciousness is, metaphorically, only so much ephemeral “steam” coming off the real engine of behavior: the purely physical activity of the brain.18 Consciousness, according to Huxley, does not enter into the actual causal nexus; it is merely epiphenomenal, a causally inert side effect. James, for whom consciousness was the chief matter separating psychology from physiology, objected to this characterization, and he did so employing Huxley’s own weapon: evolutionary theory. Consciousness, James reasoned, would not have evolved, nor would it have been retained in the very “highest” animals—humans—if it did not confer some important evolutionary advantage upon those possessing it. Therefore, he continued, conscious cannot be a simple side effect; it must have some essential role to play, at least in the most complex forms of mentality. Speculating on what that role might be, James suggested that the brains of higher animals are so stupendously complex that they are difficult to control; so delicate is the balance that keeps them functioning properly that they are liable to become erratic at the slightest random perturbation. They have “hair-triggers,” as James put it. However, he went on, if consciousness were able to “load the dice”—to use its capacity to foresee the probable outcomes of various actions to gently nudge brain activity in a beneficial direction—then the danger posed by its massive complexity could be largely averted. Moreover, James continued, this scheme would make consciousness not merely an interesting but passive phenomenon. It would, instead, make it a powerful “fighter for ends,” as he would later say.19 It would enable the organism to focus on and attain particular interests. He even went on to suggest that, with this power to affect the course of brain function, consciousness might be able to guide the course of evolution itself, shortening the time required for natural selection to meet looming environmental challenges.20

James’ response to Huxley was published the following year, 1879.21 The fact that it was published in the London-based journal Mind was probably no accident. James wanted to ensure that Huxley and his British colleagues saw it. More important, however, was the fact that there were still no journals of psychology or philosophy in the US at the time, but for the Journal of Speculative Philosophy. Mind was publishing mostly British authors at the time (save a few translations of Wundt, Helmholtz, and the French philosopher Hippolyte Taine). The only American to have appeared in Mind was Stanley Hall, with his PhD thesis in 1878. Hall would publish two more articles in Mind in 1879. The race between Hall and James to become the Grandee of American psychology was on.

James’ February 1878 lectures at Johns Hopkins were a great success, so much so that he was invited to essentially repeat them at the Lowell Institute in Boston in the fall of that year. More important, James had begun to subtly change the trajectory of American psychology. Rather than building a scientific psychology by following the established successes of German physiology, as Wundt had done, James had effectively announced that the American form of the discipline would be modeled on the more recent, more exciting (not to mention, more English) achievements of evolutionary science. But they would not follow the English example slavishly, as James’ reply to Huxley showed. Chauncey Wright’s interpretation of the implications of evolutionary theory for the study of consciousness, though perhaps hidden from most people’s view, would guide James and his circle for some time.

James’ Hopkins lectures had one other important effect that would not be felt for long while to come: they led the prominent New York publisher Henry Holt, in June of 1878, to contract James to write a new textbook on the topic of physiological psychology. The book would bring a fresh new view of the field to light, displacing the older philosophical textbooks by people like Thomas Upham of Bowdoin and Noah Porter of Yale that then still buttressed most college courses in the topic.22 Porter was particular disdainful of the new scientific developments in psychology. So far as he was concerned—and he spoke for a broad circle of American college traditionalists in this matter—the Christian soul was the vital force behind the mind and the body. The new psychology had proven itself unable to discover anything about the soul. “So much the worse for science,” he scoffed.23 Herbert Spencer’s controversial and eccentric tome, Principles of Psychology, was gathering some American followers, but it had nothing to say about the emerging experimental form of the field. It would be twelve more years before James could complete his two-volume masterwork, Principles of Psychology, but much of the outlook presented there found its origin here, in the lectures of 1878.

Despite the success of the James’ Baltimore lectures, Gilman was not able to persuade James to leave Harvard for Hopkins. Instead, James used Gilman’s offer to pressure Eliot to move his Assistant Professorship from physiology to philosophy, which Eilot did. But James was not the only candidate Gilman was wooing for the Hopkins philosophy professorship. In December of 1877, Gilman offered a single course in the history of philosophy to George Sylvester Morris, the very man who the young Stanley Hall had admired for having gone to Germany to study with Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg back in the 1860s, when they were both students at Union Seminary in New York. Morris had gone on to a chair in Modern Languages and Literature at the University of Michigan, where he had labored since 1870, but he longed for a chair in philosophy instead. He was blocked from the one at Michigan by an older and much-beloved minister who had taken up the philosophy chair just a year before Morris had arrived (so it was unlikely that he would be vacating it very soon).24 Still, Morris persevered, publishing a translation of Friedrich Ueberweg’s History of Philosophy in an effort to bolster his philosophical credentials.25

Although Morris was better established in philosophy than William James was at the time, he fit uncomfortably into Hopkins’ scientific ethos. First, he was ambivalent about the importance of natural science. Second, although devoutly religious, the approach to Christianity he had learned from his German training made him not as “safe” a candidate as Gilman believed he required to keep Baltimore’s self-appointed guardians of religious orthodoxy content.26 Despite all of this, Morris taught the course that Gilman offered him in January of 1878 and was sufficiently successful that he was invited to return the following January to give a second series of lectures, this one on ethics.

Peirce, of course, was watching matters unfold at Johns Hopkins closely. Although psychology had never really been his specialty, in 1877 he published an article in The American Journal of Science and Arts that has led one historian of the discipline to declare him to have been “the first American experimental psychologist.”27 Titled “A Note on the Sensation of Color,” Peirce called into question the assumption of Gustav Fechner, founder of the field of psychophysics, that the apparent hue of a color remains constant across changing intensities. Peirce found instead that, as intensity increased, hue tended toward the yellow part of the spectrum. He presented empirical data on his own color perception, across many trials, to determine his “photometric probable error” and to confirm his hypothesis. His work was far more rigorous, far more mathematically sophisticated than that of anyone else conducting psychological research in America at the time.

Peirce wrote to Gilman in March 1878, just after James had given his first lecture series, offering to teach logic.28 Gilman initially offered him a half-lectureship, but later withdrew it after Peirce tangled with Hopkins’s highly-valued but testy mathematics professor, James Joseph Sylvester.29 It seems that Peirce never learned the life lesson that public quarrels, no matter how learned, do not endear you to many people, especially to the administrators who are going to have to clean up the resulting mess.

Almost from the moment of its launch in 1876, the journal Mind began recruiting correspondents to write about the state of philosophy in various countries. Wundt wrote one about German philosophy in 1877.30 Having published Hall’s thesis in 1878, Mind‘s editor, George Croom Robertson, naturally turned to Hall to describe the American philosophical scene.31 Hall probably thought that the resulting article would establish his philosophical reputation. Instead, it was so damning of the general state of philosophy in the US that it likely nixed whatever chance he ever had of being called to a chair anywhere in the country. Even Harvard, one of very few places he did not relegate to the status of backwater, became less likely to ever bring Hall on board.32 According to Hall, nearly all US colleges were mired in the dogmatics of their particular Protestant denominations, taught by well-meaning but hidebound, unenlightened men who knew little or nothing of recent developments in European philosophy. Even where there was interest in European philosophy—e.g., William Harris’ Hegelian circle in St. Louis and the positivist discussion groups in which Hall had participated in New York—they were presided over by amateurs. It is not that Hall was incorrect in these observations; his vision was ruthlessly clear. It is that he would soon return to these people in search of a job, and his pointed public criticism of them would do little to enhance his desirability.

When Hall returned to the US, he had come to see his country and his own upbringing in a new and negative way.

The narrow, inflexible orthodoxy, the settled lifeless mores, the Puritan eviction of the joy that comes from amusements from [sic] life, the provincialism of our interests, our prejudice against continental ways of living and thinking, the crudeness of our school system, the elementary character of the education imparted in our higher institutions of learning… . Most of all, we were so smugly complacent with our limitations, so self-satisfied with our material prosperity, and so ignorant of Europe, save as tourists see it. I fairly loathed and hated so much that I saw about me …33

Regardless of how Hall may have felt, he was back in the US with a wife and two small children to support, living in a small house in Somerville, Massachusetts (outside of Cambridge), in debt, and unemployed. He took the offer of a course in the history of philosophy at his alma mater of Williams College, but his high aspirations of bringing to them the new German philosophy were in open conflict with the desires of his students.34 While still in Germany, he had written Gilman about the possibility of the Johns Hopkins position more than once. James offered his support, declaring even that Hall’s new German training “entirely reverses the positions we held relative to each other 3 years ago. He is a more learned man than I can ever hope to become.”35 Gilman remained unconvinced. Hall then tried to marshal James, Henry Bowditch, and Charles Eliot Norton to nominate him for a Lowell Institute lecture series, like James had given in 1878. Nothing came of it. Finally, he collected together bits and pieces that he had published in The Nation, along with some earlier scientific writings and a few new essays. He published this rather motley sheaf as a book called Aspects of German Culture.36 He wrote of the success of natural science, and of the need to reform American religion, but he avoided the strident tone of the earlier Mind article on American philosophy that had caused him such grief. Here he attempted to craft a reconciliation between religion and science by way of, on the one hand, recourse to the German “higher criticism” and, on the other hand, an end to scientific radicals’ “gross and tasteless” rebukes of religion. The book did not do well, but it reached some important eyes. Charles Eliot Norton, for instance, called it “remarkable.” Hall also published a new article in Mind on hypnosis.37

Late in 1880, when things perhaps appeared to Hall most bleak, President Eliot of Harvard rode up to Hall’s house and, without even getting off of his horse (according to Hall’s version of the story), offered him a series of lectures on the novel topic of “pedagogy.” They would be sponsored by the university, but were to be delivered in Boston so that the city’s school teachers could more easily attend them. Hall persuaded Eliot to let him give a course in German philosophy as well. This was, far and away, the best academic offer Hall had ever received. The philosophy course went well enough, but the pedagogy lectures, which began in February of 1881, turned out to be far more significant for his future career than Hall could probably have imagined.

Massachusetts was the American center of gravity for progressive ideas about education. As mentioned before, the Puritans had set up schools almost as soon as they arrived in the early 17th century. The educational vision of the era—well into the 19th century—was of the inculcation of conventional morality enforced by stern physical discipline. Breaking the child’s “will” in order to produce meek and obedient Christian subjects was the order of the day. Latin and mathematics were typically part of the curriculum, but more for the purposes of building mental discipline (which, it was then thought, would readily transfer over to other domains of knowledge) than for any particular value their content was thought to have. Learning was mostly by rote. Memorization of Bible passages and other texts with religious themes was standard practice.

In 1837, Horace Mann, a Massachusetts state legislator, became the first head of the state’s Board of Education. He began his term by personally touring and examining every school in the state. Dismayed by much of what he found, he began writing annual reports about the condition of education in the state. He promoted far-reaching school reforms. Among these were that education should be universal, and that it should be paid for from the public purse. Schools should accept children of all backgrounds and, thus, the curriculum itself should be non-denominational. The schools should be better equipped and the teachers better trained and better paid. Although Mann promoted a moral education more than an intellectual one, he advocated the discontinuation of corporal punishment in the schools.38 Although he met fierce resistance from traditionalists, many of Mann’s proposals were implemented, first in Massachusetts and, later, in New York and other states beyond.

Mann then inaugurated the “normal school” system in Massachusetts, in which teachers—primarily women, which was a novel phenomenon—were trained for the new “profession” of teaching. He organized conventions at which teachers could exchange ideas and practices, and he founded the Common School Journal in which he disseminated “progressive” educational ideas. In 1848, he returned to electoral politics, filling the US congressional seat left vacant by the death of former-president John Quincy Adams. In 1852 he ran for governor of Massachusetts, but was defeated. Only then, as we have already seen, did he move west to take up the presidency of the newly founded Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio.

About a decade after Mann’s death in 1859, the head of the nearby Dayton normal school, Francis Wayland Parker, decided to travel to Germany to learn about the educational reforms that were underway there. He became enamored of a system envisioned by Romantic philosophers such as Jean Jacques Rousseau, Friedrich Fröbel, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, and Johann Friedrich Herbart. They believed, among other things, that children’s natural dispositions should be respected and that their interests should be catered to. This would make learning a more enjoyable and, thus, more productive process. Obviously, this was all in stark contrast to the traditional American Protestant goal of “beating the will” out of the child.

In 1875, Parker returned to his original home of New England and became superintendent of the school system in Quincy, Massachusetts. There he began a grand educational experiment in which schooling was centered on the putative needs of the child, rather than on the demands of the teacher (a Copernican revolution in the classroom, it has been called).39 Rote memorization, testing, and grading were eliminated. Corporal punishment was banished. Group activities were encouraged, rather than having children sit at desks arranged in rigid rows. Arts and sciences entered the curriculum, displacing some traditional subjects. Physical education was promoted. Children were encouraged, as much as possible, to learn by means of their own experience, not just via the lecture and the textbook. Parker faced stiff opposition, but testing mandated by his opponents showed that Qunicy students were better than most others in the state.

In 1880, Parker was invited to bring the Quincy Plan into Boston’s public schools. This was the context of excitement and controversy into which G. Stanley Hall was hired by Charles Eliot to give his public lecture series on the topic of pedagogy. It was reported that Eliot, while introducing Hall to his audience, “was hardly able to pronounce the word pedagogy without evident distaste.”40 Harvard’s public show of skepticism notwithstanding, the turnout for the first lecture, in February of 1881, was large41 and included a number of prominent personages: There was the Superintendent of Boston Public Schools John Dudley Philbrick who, in the question period after one lecture defied Hall “to find any imperfection in the school system of Boston.”42 (Hall did not record his answer to so provocative a question.) There was Charles Francis Adams, scion of the great Adams dynasty in Massachusetts (Henry Adams’ older brother) and a prominent supporter of Francis Parker’s Romantic educational reforms in his distinguished family’s ancestral home of Quincy. Elizabeth Peabody, often said to be the founder of the first kindergarten in American, based on Fröbel’s model, was in attendance as well.43 In introducing Hall, Eliot challenged the audience to decide whether Hall was right in promoting the new discipline of pedagogy, or whether Harvard would be right to ignore it (which, of course, it wasn’t, having sponsored those very lectures).

For the most part, Hall tentatively endorsed the Romantic views of the child and education that were central to progressive educational reform. What made his position unique was that he substantiated these claims not so much with reference to philosophy as by way of the new scientific physiology and psychology that he had just studied so intensively in Germany. Indeed, he argued that much more scientific investigation of children—their abilities, needs, dispositions, proclivities, desires—was needed in order to make education even more child-centered; in order to make certain classroom activities fit the nature of the child as much as the advocates of progressive education insisted.

Hall’s pedagogical lectures provided the greatest academic success that he had experienced, and he moved to capitalize on them immediately by publishing two pieces in the somewhat stodgy Princeton Review.44 In the first, Hall brandished in print for the first time his psychologized version of recapitulationism: “The pupil should, and in fact naturally does, repeat the course of the development of the race, and education is simply the expediting and shortening of this course.”45 All in all, though, Hall trod rather softly; he enunciated what his primary biographer called a “timid Romanticism.”46 He acknowledged even the occasional need for corporal punishment. He did not argue with the need to inculcate Christian morality, except to displace traditional, literalist, harsh Protestant belief with the softened, historicized faith he had acquired in Germany.

In 1882 Hall was invited to speak before an audience of school superintendents at the meeting of the National Education Association (NEA). This is where his call for the scientific study of the nature of the child was transformed into the “Child Study Movement,” for which Hall deserves a great deal of the credit.47 He followed the lecture with an article in the Princeton Review that was intended to exemplify the process.48 Titled “The Contents of Children’s Minds,” it marked Hall’s most ambitious attempt thus far to put into practice the sort of research for which he had been calling. The study consisted chiefly of closely questioning children on the state of their knowledge and recording the results in tabular form. Perhaps not surprisingly, Hall found that children have substantial epistemic gaps and are misinformed about many things. As Hall put it himself, what he really conducted was “a study of children’s ignorance.”49 Nevertheless, the article created a sensation in the community of teachers and scholars who were enthusiastic about child study. Hall received dozens of inquires about it, and he turned this attention to his advantage by calling upon his correspondents to collect additional data for him. Before long he was overwhelmed with detailed records of children’s beliefs.

Hall’s biographer noted that he mostly asked questions about topics that would be more familiar to country children than to those who dwelt in cities.50 Indeed, he wrote explicitly: “As our methods of teaching grow natural we realize that city life is unnatural, and that those who grow up without knowing the country are defrauded of that without which childhood can never be complete or normal. On the whole the material of the city is no doubt inferior in pedagogic value to country experience.“51 It is easy to conclude here that Hall was unthinkingly presuming that his own childhood experience had been the “right” or “normal” experience to have. However, he may have been proposing that, as children develop by recapitulating the experiences of the species, it is more “natural” for them to start the process in a rural environment, where the human race started, rather than in the “unnatural”—for that stage of development—confines of the city:

We cannot accept without many careful qualifications the evolutionary dictum that the child’s mental development should repeat that of the race. Unlike primitive man the child’s body is feeble and he is ever influenced by a higher culture about him. Yet from the primeval intimacy with the qualities and habits of plants, with the instincts of animals—so like those of children … it is certain that not a few educational elements of great value can be selected [from the country] and systematized for children.52

Hall was soon asked to join important committees of the NEA, where he encountered, once again, William Torrey Harris (who would be appointed US Commissioner of Education at the end of the decade). Harris was less than pleased that, as he saw it, issues he had been working on steadily for over a decade were suddenly coming to prominence associated with Hall’s name instead of his. Although they largely agreed on the Romantic turn in pedagogy, Harris was still a Hegelian with little use for empirical study; First Principles and Reason alone would, in his view, lead us to the correct conclusions. Hall, by contrast, had made progressive reforms that were especially appealing in the American context by tethering them to “science.” It was Hall’s trump card.

By late 1881, other opportunities started to draw Hall away from both Boston and Harvard. After years of trying to attract the attention of Johns Hopkins’ president, it was not philosophy or physiology that brought President Gilman around to Hall’s talents, but the success of the Boston pedagogy lectures. Even before the lectures had run their course, Gilman had heard of their popularity and asked Hall to lecture at Hopkins. Hall agreed, and prepared a set of lectures on psychology for presentation in Baltimore in January 1882.

Although Gilman could not attend Hall’s Hopkins lectures himself, a report on the event from one of his faculty members was encouraging enough that, in March 1882, Gilman offered him a 3-year half-lectureship (spring terms, opposite Morris in the fall) in psychology and pedagogics in the department of philosophy. As if to reassure Gilman that he had not made a mistake, Hall formally launched his child study movement at an NEA speech that spring. Later the same year he published an empirical study of optical illusions with Bowditch.53

Baltimore was an entirely new environment for Hall. Unlike the intensely moral abolitionism of the Massachusetts in which he had been born and raised, unlike even the unsteady ethnic tolerance of New York with its keen focus on mercantile matters, Baltimore was Southern, if not Confederate precisely. Sympathy for the old landowners and against their former slaves was palpable, even at Johns Hopkins. Although Mr. Hopkins himself had been a Quaker, many of the early Trustees of the university were drawn from a “small group of wealthy men of deeply Southern loyalties and of narrow and largely Methodist and Presbyterian convictions.”54 Hall’s response was to bury himself in his work. An opportunity like this had never come his way before, and he was determined not to let it escape.

Gilman, who had opened Hopkins in 1876 with no instructor in philosophy, now had an embarrassment of riches: Morris in history and ethics, Peirce in logic, and Hall in psychology and pedagogy.55 Although the three lecturers seemed to get along well, each had reason to believe that he alone had the inside track to the professorship. One obvious option—appointing more than one professor in the area—seems not to have appealed to Gilman. The delicate state of Hopkins’ finances may well have prevented him from contemplating such a course.56

Time was not on Gilman’s side, however. In December 1880, not long after the death in September of Peirce’s father, the younger Peirce announced that he would be forced to leave Hopkins on account of some travel required by his geodetic work with the US Coast Survey.57 At that time he sold nearly 300 books from his personal collection to the school, declaring that, “upon leaving the university I shall bid adieu to the study of Logic and Philosophy (except experimental psychology).”58 By March 1881, a large salary increase had coaxed Peirce back,59 but it was clear that he was on the hunt for higher-paying work than he had in his combined Hopkins and Coast Survey positions. Peirce attempted to recreate the circumstances that had nurtured his own philosophical maturation in back in Cambridge: he founded a new “Metaphysical Club,” and played, to his students, the role that Chauncey Wright had played to him in the early 1870s.60

Morris was hunting for more as well. In June 1881, Michigan played the best hand it could muster at the time, given that they already had a professor of philosophy in place: they offered Morris a half-professorship in ethics, the history of philosophy, and logic and they tailored it specifically not to interfere with his Hopkins duties.61 If Gilman wanted Morris to stay at Hopkins, he would have to fight Michigan for him.

September 1882 saw the arrival of some exceptional graduate students: James McKeen Cattell, who had won an entry fellowship, and John Dewey, who had impressed Morris with an article he had published in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy. They joined physiologist Henry Herbert Donaldson, who had come in 1881 and was starting work with Hall on tactile perception, as well as Christine Ladd, who had come in 1878 and, although now known mostly for her work on color vision, was then primarily a student of mathematics and logic.62 Soon after, Joseph Jastrow would arrive as well to study with Peirce. Cattell, Dewey, Donaldson, Ladd, and Jastrow were all contributors to Peirce’s new Metaphysical Club,63 and all went on to significant careers in their own rights. Cattell, however, was stripped of his fellowship the following May and, furious at Hall’s duplicitous behavior in the matter,64 he barged out of the department and went on to complete his doctorate in Leipzig under the supervision of Wilhelm Wundt.65

The year 1883 saw the publication of Studies in Logic by Members of the Johns Hopkins University, under the editorship of Peirce.66 The book contained a number of significant original contributions to the field authored by Peirce and his students over the previous two years.67 The prominent English logician John Venn (namesake of Venn diagrams) was highly impressed by it, writing that it “seems to me to contain a greater quantity of novel and suggestive matter than any other recent works on the same or allied subject which has happened to come under my notice.”68 Later that year, Peirce began a series of experimental studies with Joseph Jastrow aimed at demonstrating a critical flaw in the view of perception that underlay Fechner’s psychophysical law. They presented their findings at the October 1884 meting of the National Academy of Sciences and published their report in NAS’s Memoirs the following year.69

Hall, determined that control of psychology at Johns Hopkins would be his, not Peirce’s, opened an experimental psychology laboratory on his own initiative in February of 1883.70 It was the first such facility in America dedicated to original research, but was located in a private house adjacent to the Johns Hopkins buildings.71 The first published research conducted in the laboratory was authored by Hall and the Hopkins gymnasium director, Edward Mussey Hartwell. It appeared in Mind in January of 1884.72 Jastrow later recalled that his experimental work with Peirce, which was carried out in Jastrow’s own rooms starting in December 1883, began before any research by Hall or his students at Hopkins.73 However, given that Hall and Hartwell’s article in Mind was published in January 1884, the research that led to it must have begun well before the previous month. The first publication by any of Hall’s students, based on work undertaken in the new lab, did not appear until more than two years after the lab had opened.74

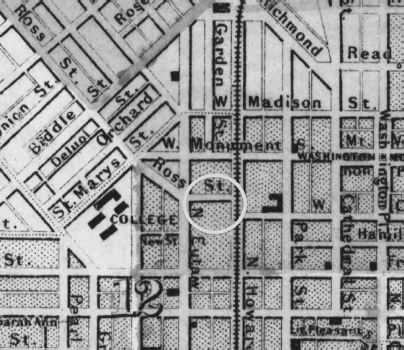

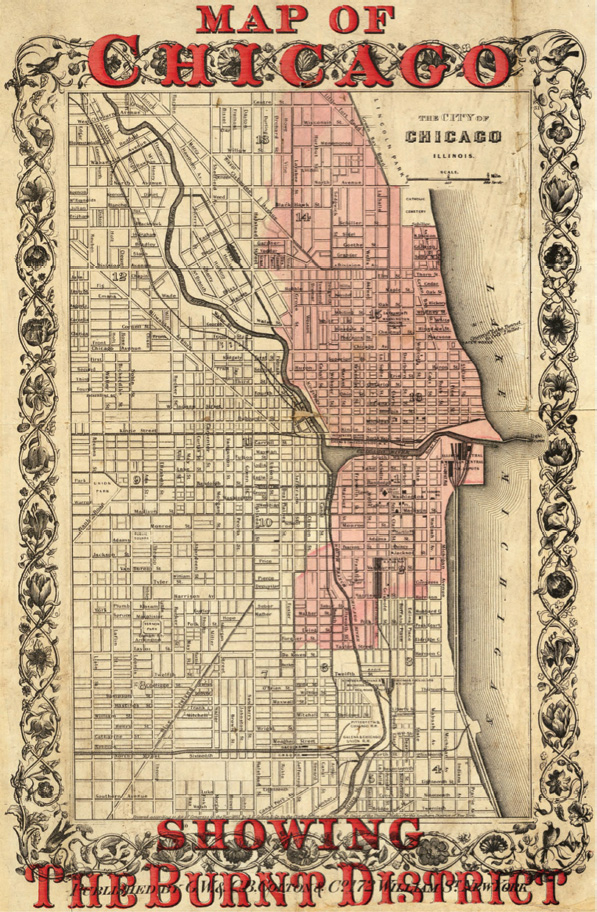

Part of the problem in founding a psychology laboratory as part of the school proper was Hopkins’ lack of a real campus in the early days. As mentioned, unable to afford to build on the late Mr. Hopkins’ estate north of the city, Gilman had started to acquire existing buildings. Then, over the strenuous objections of some of his Trustees, he began to erect new structures. Soon, the little cluster of buildings formed a kind of urban “campus” on the street then known as “Little Ross” (now Druid Hill Ave.), just west of Howard St., and across from what was then the western terminus of Centre St.75 The site was north of downtown, but not nearly as far out of the city as the objecting Trustees thought it should be. To its advantage, the location afforded easy access to the 60,000-volume library of the Peabody Institute (which was not then yet affiliated with Hopkins). It was also close to a large theater called the Academy of Music, and to Baltimore City College (just to the west in the map). But the buildings there were never wholly sufficient to house the new and ever-growing school.

Initially, two older adjoining residences at the southwest corner of Howard and Ross were converted into a single Administration Building. Then, in late 1876, just before the school officially opened, a modest new 3-story edifice called Hopkins Hall was erected just west of the Administration Building, on Ross. A chemistry laboratory for Ira Remsen was added to the west of Hopkins Hall the following year. Other departments occupied nearby houses that had been purchased by the school. By 1882, with space becoming a critical issue, the chemistry building was expanded and a new biology building was added to its west, also on Ross, about block away from Howard, at Eutaw.

Although Hall had started his laboratory in a nearby house early in 1883, he was able to move it to the new biology building by the end of the year. Other pieces fell into place for Hall during 1883 as well. In April, his old friend George Sylvester Morris won the permanent philosophical position at Michigan that he had long sought. When he left Hopkins the following year, he took with him, as an instructor, his just-graduated protégé, John Dewey. That left just Hall and Peirce to compete for the sole philosophy professorship. Peirce was, by far, the more accomplished scholar, but personal matters would intervene to decide the contest.

Peirce had been separated from his wife Melusina “Zina” Fay since 1875.76 In the early 1880s he took up with a woman of somewhat mysterious background named Juliette. Her family name was sometimes given as Froissy, other times as Portalai. Her exact identity has never been established. As the relationship with Juliette became permanent, Peirce filed for divorce from Fay. Before the marriage was officially dissolved, however, he began living with Juliette as his wife, in New York, far from Johns Hopkins. Simon Newcomb, was just starting as Johns Hopkins’ professor of astronomy and mathematics (replacing Sylvester, who had won a long-sought appointment at Oxford). As noted before, Newcomb actively despised Peirce. Upon discovering the untoward facts of Peirce’s love life, he reported them to one of the more devout Quakers among the Johns Hopkins Trustees, James Carey Thomas.77 Thomas, in turn, demanded swift and decisive action against Peirce from President Gilman.

From the start, there had been tension between Hopkins and the population of Baltimore. The first strain was regional: there were few Southerners on faculty, apart from the Classicist, Basil Gildersleeve, who had been wounded while fighting for the Confederacy. Even most of the students were Northerners, so many residents of the city saw the university as a “Yankee” or even a despised “carpetbagger” institution.78 The second conflict was religious: although there were sizeable communities of Catholics, Quakers, and Methodists in Baltimore, a particularly conservative form of Presbyterianism had taken for itself the role of civic moral arbiter. When controversy erupted, as it did from time to time—over a professor teaching evolution, or materialism, or pantheism—Gilman would quickly point to several of his faculty who were actively engaged with local churches, and to the Hopkins departments that were engaged in some of the finest Biblical studies in the country. He would even personally request his faculty to attend church regularly in order to further the goal of appearing religiously unexceptionable to wary Baltimoreans. G. Stanley Hall was among those who, although no longer much of a believer, attended church for the sake of peace between the school and the city.79

Potential conflicts with the citizenry, like that now posed by Peirce’s unorthodox marital behavior, were matters that Gilman strove to avoid at all cost, even if it meant losing one of the best minds the country had to offer. Firing Peirce outright, however, would have attracted unwanted attention and risked public scandal. So the Board of Trustees decided, instead, to implement a policy of that would limit all instructors’ contracts to just one year in length. This, of course, included Peirce. When Peirce’s contract came due in April 1884, they quietly declined to renew it. That same month, Hall, being the last man standing in the philosophy department, was offered the sole professorship in the topic (though it was officially called “Psychology & Pedagogy”). Peirce, on the other hand, would never hold an academic position again. His professional decline was rapid and permanent. By the early 1890s, his published writings had become “rambling and diffuse.”80 Christine Ladd-Franklin, who continued to see him regularly, later confided to the mathematician Edwin Bidwell Wilson that Peirce was “beginning to lose his mind early in the nineties,” and specifically cited his 1892 article “Man’s Glassy Essence” as “very definite” evidence.81 Wilson confirmed Ladd-Franklin’s evaluation: having seen Peirce lecture in 1905, followed by a long discussion, he pronounced Peirce “unintelligible” and “not coherent,” even to a mathematician of Wilson’s caliber. Wilson softened the condemnation, however, saying that Peirce had just lost the “bite of his mind.”82 On the other hand, it was in the 1900s that Peirce did most of what many now consider to be his most brilliant work on a topic that he virtually invented: semiotics, the theory of signs.

As the years drew on, Peirce was only able to find work writing dictionary entries and book reviews. He and his wife gradually withdrew nearly completely to their house in rural Milford, Pennsylvania, where they endured increasingly abject poverty. Peirce’s older brother James occasionally paid down Charles’ debts, but he died in 1906. Charles’ old friend William James occasionally arranged for paid lectures by Peirce in the Boston area, and James eventually solicited contributions for a private pension fund, of sorts. Peirce would die, nearly destitute and nearly forgotten, in April of 1914.

Hall’s willingness to advance Gilman’s efforts to ensure smooth relations between town and gown extended even to his inaugural address as a professor. Titled “The New Psychology,” the formal public lecture did not really go very far toward explaining what these innovative approaches to the study of the mind consisted in nor what discoveries and insights they had brought forth. It was, instead, aimed primarily at integrating psychology into a conventional narrative of the history of philosophy. It sought more to reassure than enlighten. After brief sketches of some of the key figures of the new psychology—e.g., Weber, Wundt, and Darwin—Hall immediately noted that:

The needs of the average student, however, are no doubt best served, not by comparative, or even experimental, but by historical psychology… . Historical psychology seeks to go back of all finished systems to their roots, and explores many sources to discover the fresh, primary thoughts and sensations and feelings of mankind.83

In part, this included, for Hall, the anthropological study of “habits, beliefs, rites, taboos, oaths, maxims, ideals of life, views of death, family and social organizations,”84 but his primary concern was to bring into the discussion the many European philosophers with whom his audience would be familiar and, to at least some degree, comfortable: Plato, Aristotle, Roger Bacon, Francis Bacon, Descartes, Spinoza, Kant, etc. He then turned approvingly to the traditional course in philosophy—syllogistic logic, ethics, etc.—but included the small plea that “every young man needs a little psychology. He must know the current facts and terms in this literature about the senses, the will, feelings, attention, memory, association, apperception, etc.” Then he carefully added the promise that even this would be couched in “copious historical allusions, and especially with their innumerable and very practical applications to mental and physical hygiene but without much of what is called physiological psychology.”85 Hall concluded with what must have been the supreme reassurance that “The new psychology … is I believe Christian to its root and centre… . The Bible is being slowly re-revealed as man’s great text-book in psychology”86 As if to add emphasis to the point, he published the address in the eminently respectable theological journal Andover Review, which bore the paradoxical motto: “thoroughly progressive orthodoxy.”87 There is hardly a phrase that better captures what Hall seems to have been attempting, not only with his inaugural lecture but with much of his early career.

In 1885, a physics building was constructed a block north of the rest of the campus, at Monument St. and Garden St. (now Linden St.). Hall’s laboratory soon followed, where it enjoyed larger quarters than it had in the biology building. Hall spent most of his time teaching psychology, but he also taught history of philosophy, as well as pedagogy classes on Saturdays. These last were open to Baltimore’s teachers (another part of Gilman’s plan to maintain good relations with the city, a tactic that Hall would later adopt himself). Hall also shared in overseeing the Bayview Hospital for the Insane for a time.88

As we have seen, the list of students who came under Hall’s tutelage at Johns Hopkins was quite extraordinary. Edward Cowles, the superintendent of the McLean Asylum near Boston came to study with Hall for one year. The two formed a lifelong friendship. Even the young future president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, was a student in some of Hall’s classes, taking a minor in psychology. In part, this acquisition of high talent was made possible by Gilman’s innovation of offering graduate students fellowships of $400.89 Harvard’s President Eliot disparaged such gestures as “paying students to come,” but the success that fellowships found in drawing outstanding students to the school spoke for itself.90 Gilman also brought in eminent speakers from around America and even Europe. These included, during Hall’s time, philosopher Herbert Spencer, evolutionists Thomas Huxley and Alfred Russel Wallace, physicist Lord Kelvin, and poets Matthew Arnold and James Russell Lowell, among others.91

Hall published regularly, but not extensively, during his time at Hopkins. In addition to the study on movement with Hartwell, mentioned above, he did work on dermal sensation with Henry Donaldson and with a student from Japan named Yuzero Motora, who would go on to found one of Japan’s first psychology laboratories.92 Hall also published research on rhythm with Joseph Jastrow. Some of Hall’s writings appeared in semi-popular periodicals, as was still common at the time. Part of the difficulty lay in the fact that there were, at that time, rather few scientific journals that catered to the kind of work Hall was doing. However, Johns Hopkins’ eminent professoriate was the wellspring from which a number of the new American academic journals emerged. There being no American journal dedicated to the new experimental psychology as yet, Hall decided to join in with his colleagues by launching a journal of his own and, in the process, make himself the primary “gatekeeper” of the American form of psychology.

The way Hall told the story in his autobiography, a man named “J. Pearsall Smith of Philadelphia, an entire stranger to me,” visited Hall one Sunday and “suggested that I found a journal and then and there gave me a check for five hundred dollars.”93 Historians have since discovered a rather different sequence of events.94 Psychical research and spiritualism were popular topics in the 1880s, not only in the US but across Europe as well. Interest in these arcane matters was not limited to the “lay” public, but also included many serious academics. Some were advocates of the psychic, but others critically investigated the legitimacy of the numerous mediums who, for a price, would put their alleged abilities at the service of the general public. In 1882, Cambridge’s professor of moral philosophy Henry Sidgwick led the founding of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in Britain. Sidgwick enlisted several other recognized intellectuals in this endeavor, giving the field a new and heightened respectability. Among these people was Sidgwick’s American friend, William James.

It is easy, with hindsight, to dismiss the whole affair as having been naïve or even foolish. But perhaps it is understandable, when viewd in historical context. The “natural historian” of ghosts, Roger Clarke, has opined that “belief in the paranormal (today) has become a form of decayed religion in secular times: Ghosts are the ghosts of religion itself.”95 If that is true today, where it has become commonplace to witness the displacement by naturalistic explanation of whole domains of knowledge that traditionally fell under religious authority, one can only imagine how much more powerful this dynamic would have been in the late 19th century, when not only the understanding of the origin of humans was being revolutionized by Darwin and his associates, but the functioning of the human body—even the mind itself—were besieged by the findings of experimental physiology and its younger cousin, experimental psychology. Spiritualism, telepathy, and the like struck many—credulous and sophisticated alike—as, perhaps, the last remaining refuge of a venerable and deeply felt understanding of the self against the relentless onslaught of naturalism and science.

Put somewhat more delicately, one might view the rising wave of interest in the psychic and the spiritual not simply as a bulwark against the encroachments of naturalism but, rather, as an endeavor in which the very limits of “Nature” were being explored, tested, and possibly revised. Innovative scientific methods were appearing in brisk succession. Probability theory, for instance, once merely a playground for gamblers, had gained new attention and respect as a scientific tool. Darwin’s successful use of the previously disdained “method of hypothesis” had served to reformulate the criteria for which investigations might count as “scientific.” Whole new realms of knowledge were successfully being opened to scientific endeavor—the elementary chemical constituents of all substances, the physiology of living things, the history of life itself, the age of the earth, and the size of the cosmos. How far these lines of inquiry might go and what secrets they might reveal were anyone’s guess. Just as the underlying principles of life had seemed an impenetrable mystery just a few decades before, perhaps seemingly occult powers and spiritual phenomena would turn out to be manifestations of a “Nature” even more magnificent and encompassing than had previously been suspected. Although individual case studies broadly outnumbered controlled experiments in the field of psychical research, the aspiration, at least, was to investigate such phenomena according to the scientific scruples of the day. That said, there were, as today, many who had made up their minds prior to embarking upon their investigations, and were mainly intent on adding a veneer of scientific legitimacy to what they were already certain to be the case, not truly to subject their beliefs to possible refutation.

In 1884, two years after the founding of the SPR in Britain, William James launched a counterpart organization on the western side of the Atlantic: the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR).96 Simon Newcomb, Peirce’s old nemesis, served as its first president. Peirce’s older brother, James Mills Peirce, a Harvard mathematics professor, was on the early ASPR Council as well. G. Stanley Hall agreed to become one of several Vice Presidents, as did his old physiology mentor, Henry Bowditch.97 Another member of the original ASPR Council of 1885 was Robert Pearsall Smith, author of the 1870 book, Holiness Through Faith, which had served as the founding document of the “Holiness Movement” in the US, a popular evangelical offshoot of Methodism. In addition, Smith was a very wealthy man, having built a glassworks in his native Philadelphia. It was Robert (not “J,” as Hall reported) Pearsall Smith who contributed $500 to Hall’s journalistic venture, and it seems inconceivable that Hall and Smith did not already know each other at the time: they had both served on the ASPR executive for two years. It also seems unlikely that it was Smith rather than Hall himself, who originated the idea of founding a journal dedicated to psychology. Johns Hopkins was at the center of the burgeoning academic journal business in America, being the birthplace of at least five other scholarly periodicals in the first decade of its existence. By launching a psychology journal, Hall was, at least in part, just trying to keep up with his senior, more-celebrated Hopkins colleagues.

The key question with respect to the content of the nascent American Journal of Psychology is what Hall’s patron, Smith, expected of the journal in return for his investment, and the degree to which Hall may have misled Smith on this matter. It seems probable that Smith expected a periodical dedicated, at least in part, to the serious exploration of psychical and spiritualist matters. The SPR had founded a research journal in England and its American counterpart required no less. What Hall produced instead was a journal dedicated explicitly to “scientific” psychology.

What Hall meant by “scientific” is difficult to fathom precisely. In the inaugural editorial of his new American Journal of Psychology, which appeared in October of 1887, he listed several types of research he thought appropriate:

experimental investigations on the functions of the senses and brain, physiological time, psycho-physic law, images and their association, volition, innervation. etc.; and partly of inductive studies of instinct in animals, psychogenesis in children, and the large fields of morbid and anthropological psychology, not excluding hypnotism, methods of research which will receive special attention; and lastly, the finer anatomy of the sense-organs and the central nervous system, including the latest technical methods, and embryological, comparative and experimental studies of both neurological structure and function.98

Hall explicitly rejected “speculative” psychology, by which he meant the old moral and mental philosophy.99 No mention was made in the editorial of either psychical or spiritual research. However, Hall notably quit the ASPR not long before the new journal launched. Buried in a review of the proceedings of the (English) Society for Psychical Research, Hall declared, to what must have been Smith’s chagrin, not only that telepathy had repeatedly failed to pass empirical test, but that “spiritualism, in its more vulgar form, is the sewerage of all the superstitions of the past.”100

Despite its grand title, the American Journal of Psychology carried mainly Hall’s own work, and that of his closest colleagues and students. Whatever his initial scientific aspirations might have been, Hall was soon scrambling to fill pages for his subscribers. There were unexplained gaps in the publication schedule. The first two volumes began in November, of 1887 and 1888, respectively. The first issue of Volume 3, however, was dated January of 1890, and the last issue of the volume did not appear until February of the following year, leaving the start of volume 4 to April 1891, nearly half a year late. The contents themselves were eclectic. Much of it was exactly what we today would expect from that time: experiments on vision and touch, psychophysical studies, expositions of what was known about memory, descriptions of new laboratory apparatus, position papers on the relationship between the “new psychology” and bordering disciplines such as neurology and education. But Hall had a wide view of the field. There were studies of applied psychology, such as one on the legibility of small letters. There were articles on psychiatric issues, such as “fixed ideas” and paranoia. There were original neurological studies, including an examination of the brain of the famed “blind deaf-mute,” Laura Bridgman about whom Hall had first written in the 1870s. There was an investigation of the roosting patterns of crows, an article on the “folk-lore of the Bahama negroes,” another on dreams, a monograph on the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, a study of logic, surveys of children’s memories and of their lies, a description of arithmetical prodigies, and a consideration of the psychology of time.

The academic boundaries of “psychology” in the early American Journal were porous, to be sure. But it is often forgotten exactly how enormous Hall’s challenge was. In essence, it was nothing less than to weave an intellectually disparate set of scientists and philosophers together into a community that shared enough common ground that they could collectively constitute a distinctive and autonomous discipline where one had not really existed before. It had to be large and stable enough that it was capable of sustaining a journal of its own in the coming years and decades. In no small measure, Hall accomplished this by calling upon his colleagues and students in the institutional communities around Johns Hopkins and, later, Clark University. That is, whatever their intellectual differences might have been, they had Hall in common with each other. In the journal’s early issues Hall attempted to nurture the nascent community’s intellectual integration by writing extensive “Notes”—summaries and reviews of the current psychological literature, wherever it happened to be published, in whatever language. The “Notes” were there, it appears, to serve as a shared knowledge base for the new discipline—a common core that any member of the community could draw upon and refer to in the knowledge that other readers would have access to it as well. Around the “Notes,” a set of research specialties arrayed themselves: in the early years there were general experimental psychology, vision, mental and moral philosophy, psychiatry, and neurology. As the community developed, experimental psychology differentiated into subspecialties such as cognition and auditory perception, and new specialties in developmental psychology and comparative psychology appeared.101

It has sometimes been complained that Hall’s insistence on publishing very nearly an “in house” journal led to unnecessary friction with psychological colleagues who were not within Hall’s immediate circle but were anxious to publicize their own work. Those on whom Hall called to assist him in his venture, though, were people of known qualities and loyalties. They enabled the journal to take flight without Hall’s having to risk depending on people outside of his (remarkably wide) circle. Getting the journal onto sound intellectual and financial footing—i.e., developing a community of dedicated contributors and subscribers—was Hall’s first order of business. Extending a hand to the wider world, once the journal had attained a measure of success, seems to have been of secondary importance to Hall.

Still, it is surprising for Hall not to have seen that by being more magnanimous he could have both improved the quality of the work in the journal (earning the journal more scholarly respect) and made other psychologists beholden to him as the editor who had advanced their careers by first distributing their work, rather than resenting him as a parochial editor who ran a closed shop.

Although Hall worked tirelessly to legitimize psychology in the eyes of his university colleagues and those of the wider population, he worked just as tirelessly to secure his own personal position within the discipline and within the university, going so far as to undermine the claims of others, even bright students of his own, whom he thought might pose a threat to his own standing.102 For instance, as mentioned above, James McKeen Cattell had held the department’s only fellowship when Hall first took up the professorship in 1883, but Hall maneuvered behind the scenes to have it stripped from him and reassigned to John Dewey, leading to Cattell’s angry departure from the university. The following year Hall refused Dewey a renewal of the fellowship. Dewey finished his degree, but soon left with Morris to Michigan. In 1885, President Gilman suggested to Hall that Morris might be lured back to fill some of the rapidly growing teaching requirements in philosophy. Hall torpedoed the proposal, claiming that his old Union Seminary hero now represented “just what ought not to be.”103 Finally, in 1887, the expanding department still in need of instructors, Gilman suggested that Dewey might be called back, or that another rising young star of the discipline, James Mark Baldwin, a recent graduate of Princeton, might be induced to come. Hall declared both to be not competent.104

In 1887, the B&O stock willed by Hopkins ceased to pay any dividends at all.105 According to the school’s early official historian, this state of affairs “hamper[ed] very seriously the work that was already being carried on.”106 In addition, Hall, despite having eliminated all challengers, was still feeling uncertain about his status at the school. His laboratory, although now in university buildings, did not receive the recognition and funding that other laboratories did. His journal did not receive the subsidy that other journals there did. It may have been, as Hall feared, that psychology was not respected as an equal of the better-established sciences. It is certain, however, that Hopkins was entering a period of extreme financial difficulty, and the elevation of upstart psychology was not the issue foremost in the minds of a Board of Trustees that was now unable to open the hospital and medical school that had been envisioned in their benefactor’s will.