3

Beginning around age eleven, Kamtchowsky suddenly found herself in a series of classroom discussions wherein the teachers wished to know if the boys were masturbating yet, and whether anything milky came out when they did. The classes were co-ed, and everyone enjoyed them. The teachers, all women in their thirties, were careful to keep their expressions serious.

Thanks to some cosmic scheduling wisdom, sex ed and civics were part of a single course that most often came right after biology. The classroom slogan “Ask anything you want to know!” attempted to clarify the relationship between happiness and knowledge by tying the concept of “body” to that of “communication,” an associative bundling that led in turn to the concept of “sexuality.” The abstract notion of pleasure presented itself as the subset of thought contiguous to the action of estrogen and testosterone upon the students’ bodies, as evidenced by the accumulation of fat in the girls’ buttocks and busts, and the swelling growth of the boys’ scrotal sacs. Sooner or later (and everyone knew it was coming) nervous laughter would be followed by a furtive glance at a classmate, who would nod in turn, and from that point on it was simply a matter of “letting oneself go,” especially for the girls, though there were no instructions given for the procedure in question.

It was only natural that anxiety would permeate the classroom. Given this diagnostic, instead of cutting the students’ vulgarities short, the teachers hardly even registered them; for the most part they merely furrowed their brows a bit, discouraging such comments while also dispensing a dose of sympathy, and even complicity. Punishment was left programmatically vague, as if it were some evil gas that prevented oxygenation from occurring within the pulmonary alveoli, and its absence thus allowed everyone in the room to breathe freely. The occasional loss of control or outbreak of violence could be foreseen, but not completely avoided. When necessary, the problem child would be asked to step to the front of the class; ever so sweetly, the teacher would make the student look like an idiot, thereby taking the royal scepter back in hand without feeling dictatorial. One teacher did however make the mistake of pushing a student too far. “All right,” she said, “if you’re really so fond of talking about your wiener, why don’t you pull it out and show it to us?” The boy obliged, then peed in the face of a female classmate, whose giggling became a horrified gasp. (At the next PTA meeting, several parents were visibly upset; they spoke of a similar case that had resulted in post-traumatic stress disorder, the victim now incapable of drinking apple juice.) During recess that same day, Kamtchowsky went to the restroom and found her panties stained with blood. It was viscous, and dark, and difficult to rinse out. Back home, she put off telling her mother for several hours.

Night came, and with it her mother’s reaction, wherein she mentioned that they hadn’t named her Carolina because they were afraid that her classmates would call her Caca. Little Kamtchowsky’s skin was indeed relatively dark, but it wasn’t because of that, her mother hastened to add. The ominously empty hallways of the girl’s mind began to fill with thoughts harboring the somber intuition that there was something repulsive, something really repulsive going on with her, and she had to hide it any way that she could. She suddenly understood that she’d known this since she was very young, because there was simply no way not to be aware of it, even if she couldn’t quite explain what it was, not even to herself.

That same year, Kamtchowsky’s mother decided that she was at last old enough to begin typing up the handwritten notebooks of her Aunt Vivi, which she—little K’s mother—was hoping to get published. She believed that aside from their indisputable historical value, the journals were possessed of a fundamental authenticity evident in their use of the present tense, the untidiness of the hurried handwriting, and a certain lack of structural coherence. She asked her daughter to correct nothing but spelling errors. Kamtchowsky’s suggestion that the project be accompanied by a raise in her allowance bore no fruit whatsoever.

Not long after Kamtchowsky’s mother had gotten married, Vivi, her younger sister, had been kidnapped while handing out pamphlets in an Avellaneda factory. Rodolfo Kamtchowsky had accompanied his new bride as she made all relevant inquiries, but in truth there was little to be done. Vivi never reappeared, though there were rumors that she’d been seen in the Seré Mansion, a secret detention center in Morón. She left behind a few flowery dresses, a broken Winco record player, and this multi-volume diary written in first and second person, wherein she described the events of her life right up to the week she was kidnapped. From the age of seventeen or so, most of the entries in her diary consisted of letters to Mao Zedong, heroic leader of the Red Army; she hid his identity by changing a single letter of his name.

The hardback, folio-size notebooks had been hidden in a leaky basement; they smelled pretty bad.

Dear Moo:

There’s some weird kind of tremor in the streets, a sense of disturbance, of madness and the future. Life, it must be. They’re not going to silence us, those sons of b------! These are some fucked-up days, Moo, black days. Both personally and politically. Things aren’t going well with L.; it’s hard not to feel like we’re growing apart. I also think he’s seeing another girl. I know that we’ve got an open relationship, and I feel like a hypocrite because it’s not like I ever told him I wanted us to be one of those little bourgeois couples—if anything, I wanted the opposite. I always supported his militant opposition to the putrid values of society. We both reject bourgeois repression, and together we’ve chosen a new path, unswerving and brightly lit but full of thorns. I know that if at some point I can’t stand it anymore, then all I have to do is get out of his way, and it will be over. But I can’t, Moo. The truth is that I love him, and it hurts me, the way things are right now. I realize that there isn’t much I can do to change things, and that if I really want us to stay together, what has to change is my way of seeing the situation.

For example, the other day he came over, and we were getting along great, drinking mate and talking, mostly about him. He told me that in his Local Party HQs he’d been reunited with a bunch of comrades from the Tendency, and everyone was very excited. I noticed that he was acting kind of weird, as if there was something he wanted to tell me, but didn’t dare. I told him that he could trust me, that I would always be here to support him—I know, maybe it sounds a little cheesy, but that’s how it came out. He took a wrinkled piece of paper out of his pocket, and read it to me:

But what kind of Argentina is this?

The people came out to defend the government they’d wanted

and the police swore at them, sent them running with tear gas, flew

after them on motorcycles and in squad cars.

Not even Lannuse ever dreamed of this.

The magnificent youth poured into the streets

to show that spilled blood was non-negotiable,

that the most loyal Peronists could never be prisoners,

that the people, victorious on March 11th

and September 23rd, could not be

forced to put up with all this, the officers

who’d repressed the people for eighteen long years

promoted for treating the people as if they were the enemy.

The people regrouped and advanced once again.

The facts speak for themselves.

When L. stopped reading, he seemed overwhelmed with emotion. I spoke gently, said that we shared the same feelings of powerlessness. (It wasn’t long ago that the crowds were chased out of Plaza Once—I hadn’t gone because I was having my period, but L. went.) He interrupted me, saying, “No, baby, it’s a poem, a poem that Silvina wrote. Boy, I shouldn’t show you things like this—they’re too intimate.” I felt myself growing red with rage, Moo, I swear. I wanted to kick him right in the you-know-what. Why in the world would he show the poem to me if it was so intimate? Then he said, “I found out her real name by accident. But nobody else knows that I know, so don’t tell anybody I told you anything.” I could feel my face burning, as if I’d just eaten a whole bag of hot peppers. He calmly put the piece of paper back in his pocket. I was furious, but hid it by speaking as fast as I could:

“So, but why, why shouldn’t you know her real name?”

“Because of our roles in the cause, Vivi, why else?”

He was dead serious this whole time. Then he got impatient with me, and a little while later he left. Forgive me, Moo, but what he read me was no poem. That the girl wrote the thing herself, fine and dandy, with any luck it doesn’t even have any spelling mistakes (here’s hoping, anyway—I swear to god, most of these Peronists, it wouldn’t surprise me to see them carrying signs urging us on to “Bictory”) but where is the poetry in it? Okay, I get it, you’re going to say that I’m judgmental, that I’ve got no feel for artistic freedom, the formless form, whatever, that I’m afflicted with that typical bourgeois blindness. (I’m happy to admit that the poem’s lack of actual poetry could in fact be a good thing, like with the music of Stockhausen, which isn’t, shall we say, all that musical.) But all of a sudden my mind was full of doubts. I bet if L. had stayed, I would have stared at him with absolutely no expression on my face.

I was in such a bad mood by then that I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t think, couldn’t do anything at all. I was so depressed that I actually started paging through a copy of Siete Días that we had there at the house. What a terrible magazine! But if that other thing was a poem, then this jeans ad in Siete Días is also a poem. (In the photo there are two guys and a girl, all wearing jeans with huge bell-bottoms, their makeup like something out of Nosferatu.)

The ghosts

were seen appearing, luminous spirits

in the penumbra of nightfall.

They were young, and they laughed at the cold.

Because they felt the caress of their Levi’s.

Soft as the light of the stars.

Warm as the glow of a campfire.

The ghosts were possessed

by the magical joy of life.

They had Levi’s.

And they sang.

But the gray ones—those who believe that joy has no place in this

world—they did not understand.

“Phantoms,” they murmured.

And locked their doors tight.

The ghosts hadn’t seen them,

had already disappeared,

singing, into the night.

Kept warm by the spell of their Levi’s.

I’m not one of the gray ones—never was, never will be. I’ll risk everything for the things that matter. I believe in my own inner world, and in my fight against the closed-off hearts of the bourgeoisie. I’m not about the individual as a solution. I’m all about the causes that affect the Third World, the poor and the working class, those who fight back day after day. I will not stand motionless beside the path, as Benedetti puts it, and no I will not calm down. Oh, Moo, I swear I’m trying to get my head around it, trying to accept the idea that L. and I are in an open relationship, but it’s just so hard. Fine, we’re all as free as you please, but it pisses me off, nothing I can do about it. The other day I went by the unit—mine, not L.’s, because if I’d gone by his we’d have ended up in a fight. So, they told me to sit down and wait, and a little while later a guy came in, dark-skinned, super cute, long curly hair, big mustache. I was glad I was sitting down so he couldn’t see that my backside’s a little flat (I told you that already). He told me his name was Fernando—I wonder if that’s his nom de guerre or his real name. “Hi, Fernando,” I said, “I’m Vivi.” Well, in ten minutes it felt like we’d known each other all our lives. I felt so strange, Moo, as if the logic of my footsteps and the cipher of my days (the signs in my dreams) had carried me there, to that little desk, once and for all. Or maybe I’m being too dramatic about it—I was reading Borges at the time and his way of thinking about how events unfold is really contagious. Later I told L. about it over the phone, and he hung up on me—he didn’t even believe me.

All the same, I don’t hold grudges—I went to see him, and gave him a copy of Libro de Manuel, because we’d both always loved Cortázar, who’s like some kind of talisman for us. I remember one time we went out for dinner at Pippo, and L. started calling me “Maguita,” as in La Maga from Rayuela, then we went back to his apartment and made love and it felt like I was floating up in the clouds, loved for the way I am, cherished by the one I loved. Moo, just so you see the difference: this time L. tore open the gift paper, looked at the book, and said that it was garbage. That in this exact book Cortázar had lost his way politically, and even more so artistically. Or vice versa, depending on which matters more to you. But how can you know that if you haven’t even read it, I said. L. is very intuitive but it’s not like he’s clairvoyant. “Well, you know, I was hanging out with Pelado Flores, and he showed me a couple of passages—totally pathetic,” was the best lie that imbecile could come up with. I realized that he must have read that article on Cortázar in Crisis, because he was just repeating the author’s taunts—he spent the whole afternoon making fun of Cortázar and calling him a bullshit firebrand, acting like such a bully, as if he were lord and master of revolutionary truth.

L. says that the hippy motto is total nonsense—why make love not war, if you can do both? “War is an aphrodisiac,” he says. “It heats up your blood just like love. Plus it’s summertime!” If he had kissed me right after saying that, I swear to god I would have led the people’s insurrection myself—the Fifth International, pro-China and pro-Viet Cong, and you know what else? After that I would have nationalized everything, thrown all that Peronist nonsense straight out the window, a workers’ insurrection pure and simple, government of the people. Oh, Moo! What I wouldn’t give to have him between my legs again, and we’d do it slow, everything he wanted, and then we’d do it again!

At about this same time in Kamtchowsky’s life, the Brazilian wave of Gal Costa and Maria Bethânia, of “Eu preciso te falar,” of “Amanhã talvez” and Rita Lee’s hit “Lança perfume,” came to an end. An extensive marketing study determined that the wave’s commercial success had been due mainly to a certain timbre in the treble equalization; apparently the sound engineers had set out to light up the same cerebral pleasure circuits that respond to cocaine. Against all reasonable expectations, the wave’s popularity was immediately usurped by César “Banana” Pueyrredón’s pop ballad “Conociéndote,” followed by a final twitch from the death throes of his career, “No quiero ser más tu amigo.” Then Kamtchowsky’s father left for Chile to manage the construction of a new factory, and she never saw him again.

The fifteen years that passed between her initiatory bloodshed and the beginning of this story proper were difficult ones for Kamtchowsky. It was all too clear that other people found her frankly unattractive, and her mother seemed to wish her dead. She suspected that she had no idea how to “let herself go,” and soon proved this with Mati, a classmate who was quite ugly himself. Kamtchowsky tried to adapt herself to his rhythm; she parted her lips lasciviously, threw her head back. Some of the “sensual” moments were frankly uncomfortable, but she did her best to please.

Mati and Kamtchowsky spent most of their time rubbing their stubby little bodies together, then staring meekly at one another, waiting for emotions to occur, mirroring each other’s expressions as best they could. The activation of their reproductive apparati was compulsively enriched by Mati’s onanistic research. While most of what went on could clearly be termed exploring (an adventurous euphemism for all activities related to physical development), the bulk of their efforts went into the process of working through the script that begins with Curiosity and proceeds into the singular experience of Romance. In fact these were two separate stages—one instinctive and animalistic, the other human and rational—and the natural thing was to progress from one to the other. Loving and being in love were also important, of course, almost as important as homework. Mati and Kamtchowsky generally got bored fairly quickly of all the thrusting and staring, put their clothes back on, and hooked up the Atari. Mati was rather chubby, with thick lips and bulging eyes that gave him the look of a stunned beetle; a few years later, during his growth spurt, his eyes would migrate toward the sides of his head, making him more of a tadpole, as if to indicate the potential that croaked softly within. That was also the period during which he discovered that he was ambidextrous in terms of jerking off and of drawing pictures with his pee in the urinals.

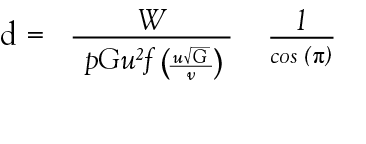

Kamtchowsky was strangely conscious of the fact that this relationship was no more than a test run for the future, and in general she let Mati have his way. She suspected that he acted as he did in order to seem cool, though he obviously couldn’t pull it off; she wanted to caress his little gel-stiffened quiff, to say that he could calm down, that they would learn soon enough. Then, much as her father had discovered how to calculate Fourier series functions at the tender age of ten, Kamtchowsky made her own unoriginal and thus trivial discovery: that fucking consisted of a set of procedures which could be serialized. Given the constant acceleration of repeated motion aligned vertically inside her (glans [G] = force vector), the mathematical operation in question would result in Kamtchowsky lying beaten to a pulp against the wall with her skull pierced along its horizontal axis (the abscissa) as follows:

When the sense of decency inherent in his self-awareness gave out, Mati dedicated himself to the art of hurting Kamtchowsky precisely where she was most vulnerable. He told her he’d figured out that she faked all of her orgasms, that she was cold as a fucking fish, that if she wanted to turn him on, she should come over here and suck him off, and if she was lucky, just maybe he’d stick a finger up her ass and cum on her tits. The two of them moaned their way through an emotional duty-free zone where erratic and relatively aggressive behaviors soon to include eating disorders, suicidal tendencies, substance abuse and stress were celebrated as rites of passage demonstrating a particular sensibility given a relatively orderly freedom to develop. Both Kamtchowsky and Mati had grown up in nurturing environments that encouraged displays of sensitivity, creativity, and originality, particularly on the raised stage that is sex, sphere par excellence of liberty and play. Kamtchowsky became furious. Something—feminine intuition?—told her that she was smarter than him, that she always had been, that she shouldn’t just let him win. She shot a glance at his crotch, let drop a particularly acidic bit of commentary, and walked out the door.

Generally speaking, successful theoretical models of standard adolescent behavior show a pattern of superficial benevolence; the empirical soil in which these models are grown, however, is swampy, demoralizing, and vulgar. Kamtchowsky’s classmates spent their post-pubescent years working through a catalog of personality vectors, each of which could be accessed by exaggerating personal details that they had come to understand, suddenly and at quite a young age, as belonging to them as individuals—which is to say, as authentic, as real. Identifying these details enabled them to draw up strategies they could use to call attention to themselves, thus giving them additional mechanisms for regulating their minimum caloric intake of personal self-esteem, in accordance with the formula whereby the audience/empathy binomial becomes an existential modality. In Bambi (1942), the fawn’s emergence in the forest initiates the hero’s apprenticeship in full view of the multitude. The creatures of the forest gather to watch him rise to his feet for the first time; his mother nudges him with her muzzle, and Bambi staggers, lurches back and forth, strains to stay upright, then tumbles to the ground. He’s charming. He’s also very young, and thus clumsy and weak, in need of attention, of care: it is by falling flat on his face that he gains the love of his woodland audience.

In order for initiational observations to be transformed into personal belief systems, the little subjects must be convinced to dive deep into their own pasts, believing wholeheartedly that within the timeline of their life there lies a key. The process of searching for ways to atone for one’s behavior naturally favors those with a predilection for dwelling on the most sordid, violent facts of one’s past—those moments when the little ones’ humanity is delineated with great quickness and clarity. Likewise, the process trains the little ones to accept as naturally as possible the camaraderie of older men and women who refuse to conform to proper models of adult behavior.

One day, however, Kamtchowsky grew up and said:

–Given the absence of any binding objective morality, we have no option but to entrust ourselves to the privacy of an ethics of mental processes. This is where a form of personal responsibility branches off. Such a system, of course, has nothing to do with any sort of Kantian obsession. At no point have I assumed the existence of any true “us” whatsoever.

Shortly after jotting down this affirmation, Kamtchowsky managed to land herself a boyfriend. His name was Pablo. He wore glasses, and paired every bodily movement with an expression of pained discomfort. They’d run into each other several times at the MALBA cinema, had watched each other from afar, but both of them thought themselves too horrible looking to be desirable even to someone who was equally repulsive. Moreover, each detected the repellent top note given off by the biographical elements they had in common. Both had quickly abandoned the simplistic comics of Anteojito for the ineffable Humi, the magazine for progressive primary schoolers; both had parents who’d never put much effort into hiding their copies of Sex Humor, giving the hormonal development of their children a completely unfounded air of natural ease; growing up, their loyal companions had been video cassette recorders, microwaves, and yogurt makers rather than some guilty-looking dog snuffling at the air and hoping for permission to defecate.

At about this time, Kamtchowsky decided to start wearing skirts: she was afraid that her backside would burst out and hurt someone if she kept trying to encage it. The eyeshadow she used was a particularly repellent shade of green, and she hid her double chin under scarves. She wore platform shoes, and socks with patterns involving microchips and circuitry. She sat near the front of the cinema to avoid the promiscuous laughter of others; there, she sprawled across her seat, sucking on chewable mints and pretending no one could see her.

Pablo had similar moviegoing habits, having cribbed them from her. Now he waited for the lights to dim, and sat down two seats away. She moved her backpack into the empty seat between them. He matched her peevishness by lowering his rucksack ever so slowly to the ground and staring at her for the rest of the film. Kamtchowsky sees everything, saw everything, but left her legs splayed wide open on the back of the seat in front of her.

The movie was Pabst’s Don Quixote (1933). Kamtchowsky ignored Pablo programmatically throughout the film. At the end he leaned over surreptitiously and whispered in her ear: “Smart-ass lil’ bitch.” Then he stood and walked away.

When Kamtchowsky came out after the credits had rolled, Pablo was waiting for her, holding a small bouquet of grass ripped out by the roots. “I’m sorry for insulting you,” he said, “but I didn’t want to come right out and say that I find you very attractive.” She made it clear that she understood perfectly, and taught him how to make her cum with a packet of Sweet Mints. And thus, though she hadn’t moved a muscle while Pablo (hereinafter known as Pabst) drilled a hole in her silhouette with his laser-like vector of ugliness, she had been reading in the most fundamental sense, had been sharing in the pertinent signs.