Chapter 1

The Meaning of Perfection

Michelangelo’s work in the Sistine Chapel is today revered as an icon of the Renaissance but provoked controversy at the time.

On March 6, 1475, Michelangelo Buonarroti was born to poor aristocrats in Caprese, near Florence. Barely thirty years later, he was hailed throughout Italy and much of Europe as one of the greatest artists of all time, a judgment of which he was keenly aware and that he would bemoan yet try to preserve throughout his life.

Michelangelo’s artistic contributions redefined Rome as the self-proclaimed “capital of the world.” In turn, the world celebrated the artist for his redefinition of beauty and expression, reclaiming the word “genius”—a term resurrected from the Latin—to describe this singular artist’s talents. Michelangelo’s contemporaries struggled to describe the phenomenal talents of a man whose work surpassed all superlatives. According to one of Michelangelo’s friends and biographers, Giorgio Vasari, God sent “to earth a spirit who, working alone, was able to demonstrate in every art and every profession the meaning of perfection.” Although many artists fade from popularity as styles and tastes change, Michelangelo’s golden reputation has never tarnished. More than five hundred years since his death, visitors still flock to see the frescoes, sculptures, and architecture with which Michelangelo adorned Rome.

A New Italy

The world into which Michelangelo was born was in the midst of a cultural and intellectual revolution, a revolution that Michelangelo’s contemporaries called the rinascita and that we know as the Renaissance. Today, the Renaissance—which swept Europe from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries—is probably best known for its innovations in art. But the artistic leaps of the Renaissance did not happen in a vacuum. They arose within a maelstrom of enormously potent political, economic, and social change. In Italy, the winds of change transformed a collection of warring principalities and city-states into the continent’s mercantile and cultural powerhouse.

The seeds of the Renaissance germinated in the grimmest of soils: the Black Death. The pandemic of bubonic plague that Italian merchants unwittingly brought to Europe from Asia in 1348 quickly swept over the Italian peninsula and then the rest of Europe, leaving millions dead and opening the door to poverty and war. In the wake of the Black Death, the city-states and kingdoms of Florence, Pisa, Milan, Naples, and Venice battled one another for dominance, while Rome, once indomitable, fell from contention. The papacy, the single wealthiest and most powerful force on the peninsula, was riven by division and moved from Rome to France.

The Black Death of the mid-1300s killed 20–30 million people in Europe, between one-third and one-half of the entire population.

But by the mid-1400s, despite the continued clashes between city-states, the environment on the peninsula had changed markedly. The papacy had returned to Rome, bringing with it a moneyed, cultured, and educated population. Venice had emerged as the center of the shipping and shipbuilding industries and become a gateway for the vigorous flow of money and goods in and out of Italy. Italy had established itself as Europe’s door to the Middle East and Asia.

The known world was expanding as European explorers discovered new lands. Christopher Columbus landed on the coast of North America. Vasco da Gama navigated around the Cape of Good Hope. Cortéz accomplished his bloody conquest of Mexico, and the Spanish conquered Brazil. The Portuguese acquainted themselves with Japan. Intellectually, horizons were being expanded as well: in 1513, Machiavelli, an exiled Florentine, wrote The Prince, a treatise on how to acquire and retain political power that achieved widespread fame because of a new technology—the printing press, which allowed all sorts of ideas, including the notion of religious rebellion, to race across Europe.

As trade flourished and navigation improved, geographic and political boundaries between East and West blurred, and the rich, spicy world of the Middle East infused Italian culture. Europe exported bulky goods like wool, timber, and semiprecious metals. In exchange, ships packed with luxuries returned, profoundly changing the Renaissance diet, wardrobe, and decoration. Spices and fabrics, plants and pigments, precious metals and jewels came to Italy from around the Mediterranean: Muslim Spain, Egypt, Turkey, and Persia. Soaps, sandalwood, and opium became popular. Dried fruits, salts, cloves, nutmeg, black pepper, and cinnamon found their way into rich dishes and baked goods served on tables laden with gilded glassware and precious porcelain. Ostentation and opulence became commonplace.

Renaissance Artists

Italians recognized the extraordinary circumstances under which they thrived. In the sixteenth century, they used the term rinascita to refer to the revival of classical culture. The word “renaissance,” from the French word meaning “rebirth,” was not used until the nineteenth century.

Art historians still follow the classifications invented by Giorgio Vasari, who identified three periods of Renaissance art. Looking at the art that surrounded him, Vasari saw the beginning of the cultural rebirth with i primi lumi (the first lights) that appeared in the fourteenth century. Known today as the “Pre-Renaissance,” this period is best known for the rediscovery of the principle of forced perspective in painting as well as a return to realism. Vasari points to Giotto and Cimabue as the finest artists of this period.

Art from the Early Renaissance (roughly, the fifteenth century), epitomized by Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence, shows a technical mastery and use of color that creates even more realism. Additionally, Early Renaissance artists were keenly aware of and influenced by ancient Rome and Greece. Donatello created the first nude sculpture since antiquity. Ghiberti and Masaccio created masterpieces that would profoundly influence those who came after them—the artists of the High Renaissance.

Michelangelo, da Vinci, and Raphael are the archetypical artists of the High Renaissance. In the sixteenth century, they perfected the use of color, perspective, and proportion and applied these tools to human and humanist subjects. The influence of the ancients was strong among the artists of the High Renaissance, but no principle was more important than Protagoras’s idea that “man is the measure of all things.” Anatomy, proportion, symmetry, and perspective permeated architecture, painting, sculpture, poetry, and music.

Ciambue’s Santa Trinita Madonna (c. 1280).

Italy in the sixteenth century.

A New Appreciation for Antiquity

The flow of goods created a thriving merchant class across the peninsula. Flush with disposable income, these merchants and their families hungered for prestige and came to believe that the path to social advancement was paved with social grace. So they spent much of the leisure time their wealth afforded them on self-improvement, especially on reading the writings of ancient Greek and Roman poets, historians, and philosophers. The concept of the “magnificent man,” as originally formulated by one of those philosophers, Aristotle, came back into vogue:

Inspired by Aristotle, Italians embraced the notion of l’uomo universale, the complete man (or, as we would put it today, the Renaissance man). L’uomo universale appreciated the arts and could speak knowledgeably about music, painting, architecture, and sculpture. He had refined tastes and manners, and was masculine and athletic. He was educated in the teachings of writers such as Dante, Boccaccio, and Aquinas as well as history and the texts of antiquity. In addition, l’uomo universale enjoyed decorating his home and his person with fine, rare, and expensive things, for the world of the wealthy was one of lush refinement. The Italian nouveau riche—and even the aristocrats they so envied—strove to behave like the “magnificent man.”

As antique sculptures were discovered in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the

papacy would take them and place them in the Vatican for contemporary artists to

study. The Belvedere Torso inspired many Renaissance artists.

This detail of a fresco created in 1441–2 by Domenico di Bartolo captures the Renaissance

zeal for both perspective and luxuriant colors and materials.

New smells, textures, colors, and tastes saturated the senses, and l’uomo universale found art in all aspects of life. Gradually, artistic beauty was demanded in everything from home décor to tailoring, furniture to frescoes. A fascination with antiquity emerged, resurrecting the power of ancient texts, ideas, sculpture, and architecture and transforming the entire Italian peninsula, especially two cities: Florence and Rome.

As artists in Renaissance Italy rediscovered the skills of the ancients, they awakened a fervor for the arts that catapulted their profession into the public eye. The public did not adopt the ancients’ attitudes toward artists themselves, however. The ancients had seen painting and sculpture as mere crafts performed by laborers; vestiges of this idea persisted through the Middle Ages. During the Renaissance, the affluent and the powerful in Italy engaged in bidding wars for the services of Italy’s greatest artists—among whom Michelangelo would soon be counted.

Like the ancient Romans, Renaissance artists tended to work in workshops, pooling resources under a strict master-apprentice system. In 1478, when Michelangelo was just three years old, Florence had a population of sixty thousand people. That population supported fifty-four workshops of sculptors, forty-four of goldsmiths, and forty of painters, according to guild records. Work was plentiful, and even peasants with talent were able to find sponsors.

As the wealthy competed for the services of the best artists, the artists competed among themselves for the most-renowned masters, the fattest commissions, and the loudest acclaim. They became faster, more prolific, and better at their craft, imitating and innovating at every turn.

A New Way of Seeing

Michelangelo embarked upon his artistic career at the height of this frenzy. As the sixteenth century dawned and he came into manhood, wealth and opportunity swirled about him. Treasure hunters actively combed Roman ruins for masterpieces of Greco-Roman sculpture. The long-abandoned ruins of the Empire became classrooms for budding and blossomed artists alike. For painters, not only were there greater opportunities to paint, but the color palette also expanded with the importation of lapis lazuli, vermilion, and cinnabar, creating velvety rich colors for frescoists.

In 1490, an ancient Greek sculpture of Apollo was discovered in an Italian villa; the Belvedere Torso, as it soon became known, was instantly revered as a specimen of unparalleled aesthetic majesty. Artists looked to ancient buildings—better preserved than they are today—and studied the classical orders of architecture and other ancient principles of construction. They admired the unity of classical designs and emulated the fine craftsmanship that allowed the structures to withstand a millennium or more of neglect.

Bella Figura

Roman women today are known for dressing with ease and grace. Men, too, spend time and money on their toilette and their clothing. Romans would never, for example, wear running shoes except when going running.

The Italian concept of dressing well, of presenting a bella figura, reaches back to the Renaissance and a time when the body was used to display wealth and exotic goods—much as it is today. The houses of Fendi and Ferragamo, Valentino and Armani all owe their roots to the grandiosity and extravagance of the Renaissance.

The achievements of Renaissance artists were many: the mastery of landscape, the use of vivid colors, the rediscovery of the nude, the portrait as an art form. But the use of perspective and its mathematical principles sets the art of the period apart. It allowed artists to achieve a greater level of realism than had been seen in Europe since ancient times.

Good Manners

In an effort to correct his fellow Romans’ manners, Giovanni della Casa (1503–56) wrote an influential treatise in 1555 called Il Galateo. In it he prescribed good manners and proper deportment—not just in royal or courtly circumstances, but also in everyday situations. The work of this Miss Manners of Renaissance Rome survives in the Italian phrase sapere il galateo. Translated as “to know the Galateo,” it describes someone with impeccable manners.

Although Renaissance artists imitated their predecessors, they also brought a new depth to art that eluded the anonymous artists of the ancient world. It is said that the ancients conveyed life in their art, but Michelangelo and his contemporaries brought souls to their figures. As they pushed to differentiate their works from those of their competitors, the Renaissance artists broke new emotional ground, depicting the solitude, tension, suffering, and strife of the human condition in vivid and unprecedented ways. Art, too, became an expression of social and religious ideas, inspiring the faithful but also stirring up controversy.

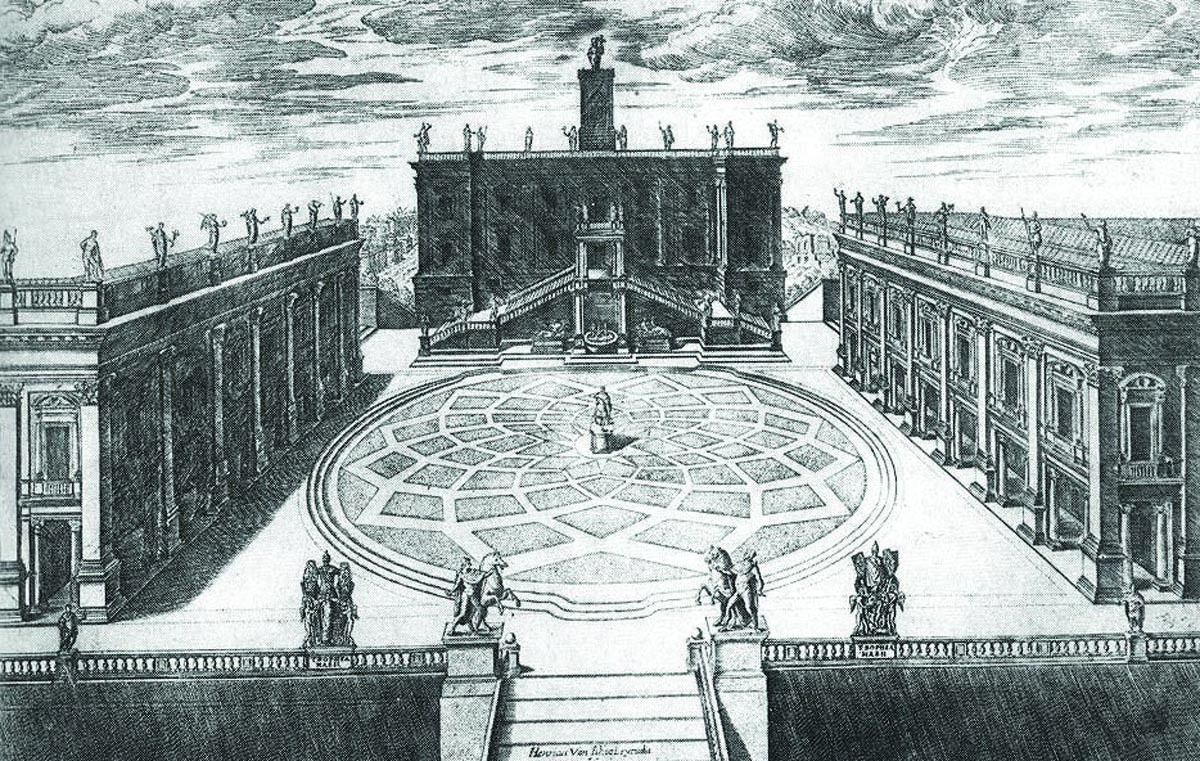

This engraving of Michelangelo’s design for the Campidoglio in Rome was made by Étienne Dupérac in 1568.

A Tale of Two Cities

Michelangelo spent almost all of his life in two very different cities. Walking the streets of Rome and Florence today, a visitor immediately sees the differences between the Eternal City and her northern cousin. Rome is a mosaic of ancient ruins, Renaissance splendors, Fascist monuments, and postmodern buildings. The streets reflect centuries of tumult, wealth, poverty, growth, contraction, and instability. In contrast, Florence looks much as she did five centuries ago. Her streets, narrow and cobbled, are lined with neat and tidy shops and apartments and illustrate the sensibilities of a city where beauty and order reigned. Florence thrived from the early days of the Renaissance, while Rome languished until the return of the pope in 1420. And whereas Florence fashioned herself as the seat of civilized gentility, Rome was a city of turmoil, greed, power, and money. In his medieval allegory, The Decameron, Boccaccio (1313–75) describes Romans as “avaricious and grasping after money” and says that “for money they bought and sold human, and even Christian, blood, and also every sort of divine thing.”

Michelangelo appears to have shared Boccaccio’s opinion—certainly, the experience of living in Rome made him long for Florence. Yet, he spent more of his life in Rome, it was in Rome that he formed his most intimate friendships, and it was in Rome that he created the lion’s share of his masterpieces.

A Journey into Michelangelo’s Rome

Because Florence rightfully claims Michelangelo as her native son, this book begins there, charting his birth and background, his artistic training and first commissions, and his relationships with a colorful family and a powerful patron. Yet, like Michelangelo, this book soon switches location and moves to Rome. Most chapters focus on a major work Michelangelo undertook while in that city of papal wealth and grand commissions. From the acclaim that greeted the unveiling of his Pietà in 1499 to the moral condemnation that was heaped in 1541 upon his frescoes for the Sistine Chapel, from the protracted controversy surrounding the design and construction of St. Peter’s Basilica to the artist’s equally lengthy but almost secretive efforts to complete the tomb of Pope Julius II, A Journey into Michelangelo’s Rome tells a story of intrigue, passion, perseverance, and a developing faith. It is a story, too, that allows the reader to traverse the city, stopping at the Forum and the Colosseum, witnessing weddings at the Campidoglio, visiting bustling markets in the Piazza Navona, and enjoying the quiet of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, before turning up Via della Conciliazione to admire the majestic dome of St. Peter’s.

Ascanio Condivi described Michelangelo as “well built; his body tends more to nerves and bones

than to flesh and fat, healthy above all.”

St. Peter’s Basilica from Ponte Sant’ Angelo.

This book presents a portrait of the artist not just as a public figure but also as a private man. Most educated Westerners identify the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel with their creator. The image of God and Adam, arms outstretched and nearly touching, has come to represent the genius of an artist and the wealth of talent that once populated Rome. The perception of Michelangelo as a suffering and temperamental artist dates back to his own time. In this myth, retold and embellished, the artist has become a figure larger than life and barely recognizable.

But just as the Sistine Chapel’s frescoes are ultimately two-dimensional representations of an idea, so too is the image of the suffering genius a simplistic view of a complicated man. Michelangelo may have relished the power his reputation afforded, and he was certainly proud of his accomplishments, quick to take offense, and often slow to forgive, but he was a very sensitive and affectionate man, devoted to his family, protective of his servants, and loyal to his friends.

As he worked on his masterpieces, Michelangelo gathered his friends together, including his confidantes, Vittoria Colonna and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, and his faithful assistant, Urbino. Through his friendships, he explored the shadows and doubts of his deepening faith. Surrounded by the trappings of papal power, Michelangelo wrestled with the questions posed by the Reformation. His theological struggles were reflected in his sculpture, the unambiguous emotional power of his Pietà giving way to increasingly pensive works, both public and private.

Although he considered himself first and foremost a sculptor, Michelangelo was forced to take on the roles of frescoist and architect as well. Political and financial considerations dictated that this intensely private man had to produce enormous public works. He reshaped the Capitoline Hill, the seat of Roman power and history. He redefined the Sistine Chapel, the seat of papal politics and continuity. And he sculpted the dome of St. Peter’s, transforming the Roman skyline and fusing the grace of the ancients with the might of the Vatican.

In his private life, Michelangelo wrote. Littered among the half-finished marbles, chisels, and stones in his workshop were scraps of paper on which he composed poetry as well as grocery lists. He wrote to others about the frustration of dealing with capricious popes who often proved reluctant to pay for what they had commissioned. He regularly corresponded with friends, acquaintances, and family members, generating a record of his feuds, joys, and griefs. A Journey into Michelangelo’s Rome draws upon this trove of writings, as well as upon the better-known artistic record, to tell the story of how, amid the ruins of the Roman Empire and the largesse of the Vatican, Michelangelo the Florentine found ancient inspiration, created ageless beauty, and earned the enduring love and respect of Romans.

In 1564, when Michelangelo died, Rome grieved deeply. From then to now, he has been honored and celebrated by a city with a long memory and a rich past. Romans consider themselves experts on their adopted son. They name their streets, their hotels, their restaurants, and even their children for the man who shaped their city half a millennium ago. A Journey into Michelangelo’s Rome explores this city, this man, and the world that shaped them both.