Chapter 2

Florence

Finished in 1434, the dome

over Santa Maria del Fiore

dominates the skyline of

Florence. Having grown up

in its shadow, Michelangelo

drew on it as a precedent

for his dome over St. Peter’s

Basilica in Rome.

The Medici coat of arms.

Michelangelo was born in 1475 to parents living in genteel poverty. The family lived in Caprese near Florence, where Michelangelo’s father, Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, had a minor government appointment. His mother, Francesca Neri di Miniato del Sera, fell from a horse during her pregnancy; happily, the fall did not seem to affect the child she was carrying.

Lodovico had married Francesca a few years before, in 1472, when she was about seventeen and he was twenty-seven. The proud father wrote of his son’s birth:

As was typical for a child from his social class, Michelangelo was sent to live with a wet nurse for his first few years. The nurse was the daughter and the wife of stonemasons, leading Michelangelo to jokingly declare, “If I have any intelligence at all, it has come ... because I took the hammer and chisels with which I carve my figures from my wet-nurse’s milk.”

Michelangelo had four siblings: one older brother, Leonardo, and three younger ones, Buonarroto, Giovansimone, and Gismondo. Their mother died in 1481, the year Gismondo was born. Michelangelo’s sensitive images of women with their children—from the Rome Pieta to the mothers on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel—reflect the longing of a boy who was motherless from the age of six.

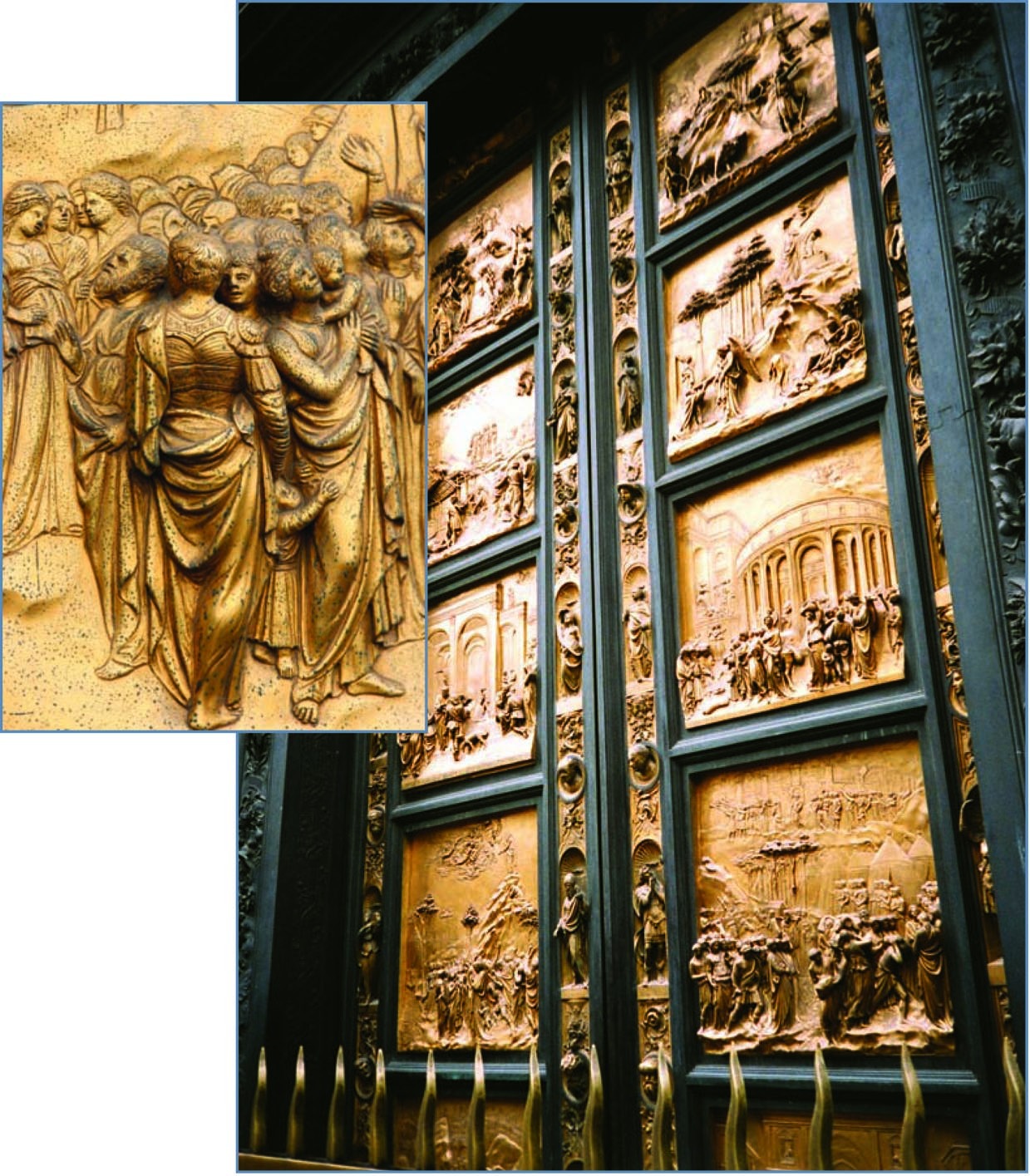

Michelangelo’s portrayals of women were also shaped by the rich beauty of his hometown; Florence in the fifteenth century was a city of prosperity, elegance, and artistry. From Ghiberti’s bronze doors on the baptistry of Santa Maria del Fiore depicting detailed friezes of Biblical stories, which Michelangelo would call “the Gates of Paradise,” to Brunelleschi’s dome and della Robbia’s medallions on the Ospedale degli Innocenti, the city through which young Michelangelo wandered was filled with art on public display. After all, the Medici family had planned it that way.

The Medici Family

For all intents and purposes, the Medici family ruled Florence during the fifteenth century. Officially, the city-state was a republican oligarchy ruled by the Signoria. This council comprising nine citizens chosen by lots every two months was composed of the gonfaloniere of justice, a man chosen as the standard bearer for the Republic, and eight priori. However, the Medici family wielded its power to rig drawings in its favor, buying the loyalties of any eligible man they could. And the public, by and large, did not object. In fact, most Florentines were content to have the Medici in charge.

The Medici fortunes came from the banking industry. The Florentine gold florin had established itself during the Middle Ages as one of Europe’s major currencies. Whereas Venice’s economy flourished because of sea trade, Florence’s grew due to her industry—wool and cloth production—and an intricate international commercial network developed during the Middle Ages. The funds flowing in and out of the city required bankers, and the Medici family became the most prominent banking family in Europe. Cosimo the Elder (1389–1464) and Lorenzo (1449–92), both brilliant statesmen and brutal strategists, wielded their power firmly but fairly and fostered a culture of loyalty and economic stability that allowed them to rule Florence for nearly a century.

The Medici were not the only family of prominence in fifteenth-century Florence, however. The Strozzi, Pitti, Pazzi, and Capponi families also had large fortunes and were active political players. They too funded great art projects, and with so many fortunes devoted to public beautification, Florence became a city of visual drama and the seat of good taste.

Florence’s pantheon of celebrated artists includes talents from many genres and media. In designing and raising the dome over Santa Maria del Fiore—or, as it is known, Il Duomo—Brunelleschi built the largest dome since antiquity, a marvel completed in 1434 (just forty-one years before Michelangelo’s birth). Giotto, a celebrated frescoist, designed the bell tower at the same church, and Ghiberti designed the bronze doors for the church’s baptistry. The city’s churches, public spaces, and private homes were adorned by sculptor Donatello; by painters Cimabue, Fra Angelico, Botticelli, and Masaccio; and, by the ultimate in versatility, Leonardo da Vinci, who wrote books, painted canvases, and designed a helicopter, among hundreds of other inventions.

Santa Maria del Fiore’s dome impresses with its scale, but a stunning, smaller masterpiece adorns the east entrance to the baptistry. Ghiberti’s doors, created between 1425 and 1452, feature

ten small panels. Each

panel vividly illustrates

an Old Testament story.

The doors on display

today are reproductions

of the originals, which

were moved inside to the

Museo dell’Opera del

Duomo (just to the east

of Il Duomo) so that they

would be protected from

the elements.

Not only did the Florentine atmosphere cultivate visual artists, it also fostered writers who followed in the footsteps of Dante, fourteenth-century creator of the Divine Comedy. Poets Petrarch and Boccaccio joined the political philosopher Machiavelli and art historian Vasari on the list of Florence’s greatest sons. Their works became enormously popular in large part because of a technological revolution—the printing press—and an intellectual movement—humanism.

The Printing Press

The Vatican Library, now considered one of the finest and most exclusive collections in the world, consisted in 1420 of just three hundred volumes. Soon thereafter, fifteenth-century Italy was consumed by a manuscript-collecting craze. Manuscripts, chiefly texts by Greek and Roman philosophers, were copied by hand in monasteries across Europe and became highly prized. The wealthy and learned competed to acquire the most beautiful manuscripts as pieces of art as well as symbols of knowledge. Pope Nicholas V (1447–55), an avid collector of manuscripts, ransacked monastic libraries in search of ancient Greek and Latin texts.

In 1450, an invention in a small town in Germany would redirect this bibliophilic fervor and prove to be the most influential invention of the Renaissance: the printing press. The first printing press arrived in Rome by 1465; soon thereafter, the ancient texts so treasured in Italy were being printed cheaply and efficiently in Italy itself.

To illustrate the dramatic impact of the printing press, consider this: forty-five scribes could, under ideal conditions, produce a maximum of one hundred manuscripts in a one-year period. The first printing press in Rome, run by two Germans, Sweynheym and Pannartz, printed twelve thousand books in its first five years of production. By the 1480s, there were more than one hundred presses in Italy.

By 1500, fifteen million books had been printed in Europe—more than the sum total of all manuscripts produced in the preceding millennium. In the sixteenth century, more than 150 million books were published in England alone, a country with a population of only four million people. Suddenly, a library of three hundred volumes looked a bit small.

A sixteenth-century image of a printing office

showing the compositor, the printers, and the

proofreader at work.

The first printed books were religious in nature: Bibles, sermons, and catechisms. Before long, the presses were printing secular books, including editions by classical authors such as Aristotle, Socrates, and Cato. In 1530, a printed pamphlet cost the same as a loaf of bread. A copy of the New Testament cost the equivalent of a laborer’s daily wage. A literary—and a literate—culture emerged.

Religious books were initially published in Latin or Greek, the languages of the church, but texts soon appeared in the vernacular languages of the day—languages for which standardized forms of spelling, grammar, and punctuation did not exist. Over time, the language of the people became as standardized and codified as the language of the clergy. Trade, politics, and business had all once been conducted in Latin or Greek, but eventually vernacular languages were used in these exchanges, too.

The dissemination of ideas through printed text shaped the Renaissance. Part of a gentleman’s training in Renaissance Italy was an education in the works of antiquity. Now educators were able to market new ways of learning and study to an eager public. Politicians and theologians sought to sway opinion with a torrent of tracts, treatises, and pamphlets.

A Humanist Education

Around the time of his mother’s death, Michelangelo started school, but he was a reluctant student. He was tutored by a humanist scholar, Francesco Galatea of Urbino. Humanism, an intellectual movement that grew out of an increasing demand for intellectuals in the changing Italian economy, spawned hundreds of small private schools devoted to educating the merchant class and the children of the working nobility. Rooted in the studies of ancient Greek and Roman texts, humanism flourished as the printing press made texts widely available.

A humanist education offered two things. First, so the humanists claimed, those who read and understood the classics were more moral and made wiser decisions. Second, students could learn the skills needed to become lawyers, politicians, or priests. Harkening back to the ideals of ancient Rome, the humanists regarded service as the perfect employment for an educated and thoughtful populace.

At school, Michelangelo studied the classic texts. Students first would read a text in the original Latin or Greek. Then they would translate the text into Italian—a task that measured true comprehension. Students also learned letter writing and public speaking, making them employable in a range of fields.

Michelangelo described himself as a poor student who scribbled and drew rather than mastering the Latin grammar before him. “Although he profited somewhat from the study of letters,” remarked Michelangelo’s biographer and contemporary Ascanio Condivi, “at the same time nature and the heavens, which are so difficult to withstand, were drawing him toward painting; so that he could not resist running off here and there to draw whenever he could steal some time and seeking the company of painters.”

Michelangelo’s father, Lodovico, was old-fashioned; he didn’t want his son to become a painter, which he considered beneath his family’s social position. But Lodovico also took great pride in being a distant relation of Lorenzo de’ Medici, and Lorenzo, a tremendous patron of the arts, did not consider painting to be a lowly trade. But the fact remained: no Buonarroti had ever been an artist. Both Michelangelo’s father and his uncle Francesco beat the young Michelangelo in an effort to change his inclination.

An Apprenticeship

After many battles, Michelangelo’s father was finally forced to acknowledge his son’s driving passion. Lodovico then approached Lorenzo de’ Medici, hoping to secure an apprenticeship for his son. Lorenzo arranged for the young man to apprentice with Domenico Ghirlandaio, a Florentine master frescoist, under a contract that paid Michelangelo substantially more than a normal apprentice.

By the age of thirteen, Michelangelo was working in Ghirlandaio’s workshop. According to legend, he was so bored by the drudgery of preparing paints and caring for brushes that he set out to better his master rather than imitate him. At one point, he copied a portrait painted by Ghirlandaio and then switched the copy with the original, a trick the master did not detect.

Michelangelo displayed an intense curiosity and work ethic early on. As a young pupil, a biographer noted, he would “go off to the fish market, where he observed the shape and coloring of the fins of the fish, the color of the eyes and every other part, and he would render them in his painting.”

During Michelangelo’s apprenticeship, Ghirlandaio worked on the Tornabuoni Chapel in Santa Maria Novella. As Ghirlandaio’s apprentice,

Michelangelo spent most of his time performing routine tasks such as preparing colors. But Michelangelo was also able to work on sketches

and to study Ghirlandaio’s techniques for dividing space and telling stories through his lifelike figures, such as in The Nativity of the Virgin.

The relationship between master and apprentice eventually soured, however; in his later years, Michelangelo claimed to have learned nothing

from Ghirlandaio.

Like many young, brilliant men, Michelangelo was cocky. One day, Pietro Torrigiano, a fellow apprentice, had had enough. “Buonarroti had the habit of making fun of anyone else who was drawing there, and one day he provoked me so much that I lost my temper more than usual, and, clenching my fist, gave him such a punch on the nose that I felt the bone and cartilage crush like a biscuit. So that fellow will carry my signature till he dies.” Indeed, in portraits of him as a grown man, Michelangelo’s nose appears somewhat misshapen and flattened.

Michelangelo’s apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio did not last the three years intended. He soon captured the attention of Lorenzo de’ Medici—with a forgery. Michelangelo carved a small faun, imitating an antiquity, which caught Lorenzo’s eye. Jokingly, Lorenzo told the young man, “Oh, you have made this faun old and left him all his teeth. Don’t you know that old men of that age are always missing a few?” When Lorenzo left the room for a few minutes, Michelangelo quickly removed one of the faun’s teeth. When Lorenzo returned, he told Michelangelo that he wished to speak with his father and invited Michelangelo to work for him at the Medici Gardens.

Michelangelo and Il Magnifico

Florence was one of the most powerful city-states in Italy due in large part to the presence of the Medici family, “God’s bankers,” who helped the papacy deploy its wealth across the continent.

Forgery

That Michelangelo was involved in forging antiquities was not remarkable. The fever for antiquities among the art-loving public created a market for forgeries, and most Renaissance sculptors committed forgery to pay the bills, at least until they established their own reputations. Because artists learned to create through imitation, they were well-equipped to create fakes.

One of Michelangelo’s projects, a sleeping cupid (now lost), caught the eye of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, a cousin of the great Lorenzo. Medici suggested that Michelangelo age the sculpture and try to pass it off as an antiquity. He said, “If you buried it, I am convinced it would pass as an ancient work, and if you sent it to Rome treated so that it appeared old, you would earn much more than by selling it here.”

Michelangelo agreed to the deception. Accounts are foggy as to what happened next. The sculpture, it seems, was sold to a cardinal in Rome, but Michelangelo was cheated out of his money by his intermediary.

The cardinal discovered that he had been tricked into buying a forgery and demanded his money back. Vasari, Michelangelo’s contemporary and his most famous biographer, claims that the cardinal’s reputation was damaged because he “did not recognize the value of the work, which consists in its perfection, for modern works are just as good as ancient ones when they are excellent.” But Vasari wrote with the benefit of hindsight; in the early days of Michelangelo’s career, ancient works were more valued than those of contemporary artists.

In recent years, some scholars have suggested that Michelangelo may have pulled off the greatest forgery of all: the celebrated Laocoön. In 1506, Pope Julius II asked Michelangelo and his friend, Giuliano da Sangallo, among others, to identify and authenticate a sculpture that had been discovered in a vineyard near Santa Maria Maggiore. The sculpture was identified as a work described in Pliny’s Roman histories from the first century A.D. and lost for more than a millennium; the pope purchased it for an enormous sum. One theory is that Michelangelo, schooled in the art of forgery, carved Laocoön during his first trip to Rome and buried it to be “discovered” at a later date.

Lorenzo de’ Medici considered the city of Florence his own personal beautification project. Whether he was securing patrons for artists, arranging marriages, striking financial deals, or sponsoring pageants and carnivals, he aspired to bring beauty to the city. He also saw his civic works as a means to justify the money he made from banking, traditionally regarded as a sinful occupation.

Lorenzo de’ Medici, known widely as Il Magnifico, headed the family empire with a keen skill for diplomacy. Taking a page from the Roman emperors’ book, Il Magnifico helped to ensure peace and harmony in Florence by keeping the public entertained. He commissioned large-scale art projects and sponsored festivals and pageantry. In doing so, he also funded a flourishing arts community and helped to foster an intensely creative and intellectual environment. Lorenzo loved Dante and wrote sheaves of poetry—both sacred and scandalously sensual. As a poet, he used the Tuscan vernacular, setting a precedent for many Tuscans who put pen to paper, including Michelangelo.

Michelangelo’s decision to leave Ghirlandaio’s workshop for the Medici Gardens could not have pleased his father, who saw his son leaving one questionable profession for another even more pedestrian. Sculpting was dirty, physical, and exhausting work. Most sculptors were employed in creating decorative elements and architectural embellishments, a trade for commoners.

To Michelangelo, however, nothing was more prestigious than to have Il Magnifico as a patron. The Medici Gardens was not a school with a curriculum or instructors. Rather, it was an informal gathering place for sculptors, philosophers, and poets dedicated to the study of antiquities and classical texts. When Michelangelo arrived at the Medici Gardens, he entered a world of intense intellectual pursuit and political savvy, which he had to navigate with skill. And he found himself riding the coattails of one of the most powerful men in the world.

The Palazzo Vecchio overlooks the Piazza della Signoria, where the religous zealot Savonarola and his

followers burned “sinful luxuries.” Today, a copy of Michelangelo’s David resides near the same spot

where Savonarola himself was burned in 1498.

The Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1489–92).

Michelangelo lived in the Medici house for nearly two years, and he worked on his first two surviving sculptures there. Both The Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1491) and The Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1489–92) show the imagination and skill of a young man who had impeccable classical models to study. As with his academic studies, Michelangelo’s artistic instruction consisted largely of imitation. Whether with the brush, the chisel, or the pencil, imitation of works by masters was considered the finest form of instruction. So an apprentice copied the works of his master over and over until he was deemed skillful enough to procure his own work. Michelangelo proved an exemplary mimic.

In 1492, Michelangelo’s patron died. The power vacuum created with Lorenzo’s death changed Florence irrevocably and set the seventeen-year-old Michelangelo on a course toward Rome. For two generations, the Medici family had ensured peace in Florence by pleasing the public and influencing the city’s ruling body, the Signoria. The success of this strategy depended on it being executed with both political cunning and diplomatic activity. Lorenzo’s son, Piero, had neither talent.

The Bonfires of the Vanities

Michelangelo cultivated an image of perfection and genius, learning from an early age to destroy pieces he did not deem worthy. Very few sketches remain from his enormous volume of work, and nothing is left from his days as a student. This contributes to the mythical fog shrouding his reputation and bolsters the perception that he was a genius, born not trained.

Michelangelo’s proclivity for burning his materials may have stemmed from the influence of Florence’s fieriest preacher, Girolamo Savonarola (1452–98). The passionate orator thrived on discontent and disaster, heating up the political climate of the city with his graphic and violent prophecies. When Lorenzo de’ Medici died in 1492, Savonarola seized power in the city. Michelangelo, who from a young age had shown intense religious devotion, identified with Savonarola’s gloomy vision for mankind and his apocalyptic view. But Michelangelo’s admiration for Savonarola was tested by the latter’s rejection of the Renaissance, Plato, the value of art, and the influence of the ancients. Savonarola’s army of “angels”—children and young men dressed in white robes—roamed the city, informing on their families and neighbors and seizing works of art, lavish clothes, and other items that Savonarola frowned upon.

In the Piazza della Signoria at the center of Florence, Savonarola and his angels built enormous fires—”Bonfires of the Vanities”—into which they threw wigs, perfumes, soaps, playing cards, chessboards, manuscripts, and other luxuries that Savonarola deemed sinful. Such an environment was extraordinarily uncomfortable for the artists of Florence, who fled to Rome and Venice to escape the same fate as their works.

Savonarola’s fervor infected Michelangelo, causing him to ponder theological questions long after the bonfires were extinguished. Vasari wrote, “As the admirable Christian he was, Michelangelo took great pleasure from the Holy Scriptures, and he held in great veneration the works written by Fra Girolamo Savonarola, whom he had heard preaching in the pulpit.”

In adulthood, Michelangelo’s proclivity for destroying his work antagonized his followers, who realized that the work of a celebrity would be valuable someday. It was a habit he maintained to his last days, however. Any doodles, poems, sketches, and letters that betrayed weakness all met a fiery end.

With Lorenzo’s death, potent powers in the city-state sensed weakness and pounced. Savonarola, a Dominican priest who had been advocating change and piety from the pulpit, unleashed a torrent of political fury and apocalyptic prophecy. Preaching Old Testament vengeance and disaster, he damned Florence for its decadence and passion for beauty. Ultimately, he would turn on the papacy and the Medici family.

Amid the turmoil, Michelangelo spent the next few years flitting between Florence and her neighbor seventy miles to the north, Bologna, as the fortunes of his patrons rose and fell. Fiercely independent, unlike many of his contemporaries, he refused to join a workshop. But as the artists of Florence fled to Rome and Venice, Michelangelo found himself increasingly alone. He decided it was time to make a change. Il Magnifico’s cousin Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici wrote some letters of introduction for the young sculptor. Armed with the letters and ready to prove his abilities in a more hospitable environment, Michelangelo set off for Rome.