Chapter 3

Rome

The Roman Forum was the heart of the

ancient city and the center of both its political

and its religious life. By the time Michelangelo

wandered through the ruins, sheep and cattle

grazed among the toppled columns and

sculptures. As Rome was rebuilt, however, the

Forum became a popular place to find building

materials. Doors, columns, sculptures, and tons

of marble were spirited away from the ruins

and recycled in Renaissance buildings all over

Rome. Today, it is both a public space for all to

enjoy and an active archaeological site.

Civic and religious authority have always mingled in Rome. Since the days when emperors were worshipped as gods, the line between spiritual and earthly powers in Rome has been fuzzy. Indeed, the principles of the empire’s organization influenced the organization of the Christian church, with bishops governing dioceses just as Roman governors ruled provinces.

At its peak, the Roman Empire dominated the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Europe. The vast size of the empire, however, overstretched Rome’s ability to administer and protect it, and with rampant corruption sapping the empire’s political vitality, the Barbarian tribes from northern and central Europe eventually overran imperial defenses. In 410A.D., Rome was sacked by the Visigoths; the empire dissolved completely in 476, when a Germanic Barbarian king deposed the last Roman emperor. Had it not acquired land and begun to establish political control over what would become known as the Papal States, the church might also have fragmented more than it did and eventually disappeared. Instead, successive popes during the Dark and Middle Ages seized territory, waged war, negotiated treaties, and generally behaved much like the kings and princes who carved up Europe in general and Italy in particular. As the cities in Italy fortified themselves during the Middle Ages, so too did the Papal States.

The city of Rome lay within the borders of the Papal States and was governed by the pope. Thus, as the pope’s fortunes rose and fell, so did those of the city. During the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, while the papacy was preoccupied with the Crusades—a series of military campaigns launched to recapture parts of Europe and the Holy Land from Muslim control—the city of Rome actually shrank. At the peak of the Roman Empire, Rome had boasted a population of 1.5 million people. Now a smaller and smaller population huddled in the shadows of the imperial ruins and clung to themily. filthy shores of the Tiber, contending with frequent floods and outbreaks of the plague. By the twelfth century, Rome was little more than a large village, with just 17,000 inhabitants.

Piazzas, like Piazza Navona, have for centuries been an integral part of the

Italian way of life, serving as living rooms, yards, markets, and parks.

Gone were the efficient sewage systems and functioning aqueducts of the Roman Empire. Drinking water was drawn primarily from the Tiber, the same river where waste was dumped—that is, if waste made it farther than the street outside the home. Most Romans lived in what today we might call tenements and row houses. Medieval Romans built relatively little compared to the Romans of the empire. Most of what they did build was constructed around piazzas, which, then as now, were noisy, social places lined with shops and markets and, in many cases, boasting fountains and public taps for the neighborhood.

A Church Divided

The pope, the spiritual and political leader of the Catholic Church, is elected from and by the College of Cardinals, a group of advisors, each of whom represents a different part of the Catholic world. By 1300, the appointment of cardinals had become a highly political process often involving the exchange of large sums of money, political favors, and even murder. The cardinals and archbishops closest to Rome wielded the most power. Influential families and foreign governments jockeyed to install their favored candidates as cardinals, in the process creating a continually shifting network of power, corruption, and greed that dominated Rome’s political life. Within the city, feudal families such as the Ferrara, the Este, the Rimini, the Colonna, and the Orsini vied with one another for supremacy in struggles that often turned bloody.

After much political maneuvering, the French wrested control of the College of Cardinals and succeeded in electing a French pope, who in 1305 whisked the papacy to Avignon, fearing for his life. The Italians refer to this period as the “Babylonian captivity,” and bitterness about this event helps explains why very few non-Italian popes were elected. (After the death in 1523 of Adrian VI, a Dutchman, the church did not have another non-Italian pope for 455 years.) As the papacy went to Avignon, so too did money, the educated classes, and political power. Pope Gregory XI returned to Rome in 1377, but within a year the papacy again fell apart, descending into four decades of strife known as the Great Schism, during which two—and sometimes even three—popes claimed legitimacy at the same time. Without a leader, Romans were left to the mercy of brutal condottieri (mercenary leaders) and foreign kings who pillaged and plundered the city.

Romulus and Remus

Why is a she-wolf with two boys at her teats a symbol of Rome? According to legend, twin brothers Romulus and Remus were the sons of Mars, the god of war, and Rhea Silvia, a priestess. Rhea Silvia’s father and uncle were locked in a bloody power struggle for their kingdom. Her uncle, Amulius, wanted his brother’s bloodline to run dry, so he kidnapped the twin boys and set them adrift on a raft on the Tiber River. He never imagined the infants would survive.

The gods were watching, however, and they protected the boys, bringing their raft to shore far from Amulius’s reach. There, a she-wolf found them. She suckled the boys and raised them until the three were discovered by a shepherd. He took the boys home, and they grew up in his care.

As young men, Romulus and Remus regained control of the kingdom their father had lost to his brother. But the younger brothers quarreled over where to establish their new city. Romulus killed Remus and then established Rome on the Palatine Hill, the place where the she-wolf had found them.

The Capitoline She-Wolf, with twins Romulus and Remus suckling at

her teats, is a ubiquitous symbol of ancient Rome. The statue was

donated in 1471 by Pope Sixtus IV to the people of Rome and

became one of the first items in the collection of the Musei

Capitolini. The figure of the wolf dates to the fifth century B.C.; the

twins were added some time in the sixteenth century. A replica of

the famous bronze resides in the Campidoglio.

Why Did Rome Become the Seat of Western

The events of Jesus’s life as presented in the New Testament all occurred in the Middle East, and Christianity began as a reformation movement within the Jewish community in ancient Israel. In the first century A.D., the Middle East was part of the Roman Empire. After Jesus’s death, his disciples and missionaries spread across the empire and beyond. According to tradition, Jesus’s disciples Peter and Paul both came to Rome.

Christian communities in Rome date to 40A.D. and were tolerated, more or less. By 313, Christianity was a recognized religion in the empire. Emperor Constantine initiated an effort to codify and organize the religion in earnest. Constantine’s efforts were not purely spiritual in nature, however. Doctrinal conflicts were occurring within Christian communities spread across the empire, threatening its stability. By imposing doctrinal conformity, Constantine was also imposing political unity in the far-flung empire.

Before his death, Jesus had said to Peter, “And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” The papacy bases its earthly and spiritual authority on this passage. St. Peter, often depicted by painters and sculptors as holding two keys, is acknowledged as the first pope by Christians, though the title was bestowed posthumously.

As later Christians organized the church leadership, they looked to the Roman Empire for inspiration and divided the church geographically into dioceses, appointing bishops to oversee them. The bishop of Rome, who oversaw the most powerful diocese, became primus inter pares (“the first among equals”), and successive popes developed an elaborate administrative and canonical system to consolidate and wield their power. The system evolved as a patriarchy, with only men holding leadership positions. (The word “pope” comes from the Latin word papa and the Greek word pappas, both meaning “father.”) Traditionally, all archbishops (administrators who oversee multiple dioceses) were assigned to a church in Rome regardless of where their dioceses were. This created strong ties to the city, even for far-flung archbishops.

For centuries, San Giovanni in Laterano—not the Vatican—has been the seat of the papacy in Rome. The first church on the site now occupied by San Giovanni in Laterano was a basilica built in the fourth century by Constantine. When the papacy moved to Avignon in the 1300s, the church and the papal palaces crumbled from neglect. After the pope’s return to Rome, he moved across the river to San Pietro in Vaticano. The Vatican remains the papal residence, but San Giovanni in Laterano is still the official seat of the bishop of Rome and the City’s Cathedral.

St. Peter is often portrayed with two keys in his hands. One represents the key to heaven, or his spiritual power; the other represents the key to earth, or temporal power. This statue is by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the last architect to work on St. Peter’s. Bernini designed the colonnade in Piazza San Pietro. Along the top of the colonnade sit 164 statues created by the sculptors in Bernini’s workshop. All told, the figures took more than a century to complete.

Order returned with the Council of Constance in 1417, which ended the dual papacies with the election of Martin V. When he came to Rome in 1420, Pope Martin “found it so dilapidated and deserted that it hardly bore any resemblance to a city.” He recognized that the shabby city needed a physical manifestation of the papacy’s claim to power. In other words, he needed to build.

Martin V, a gifted administrator, began to reassert the control the popes had once exercised over all corners of the Papal States. In Rome itself, he not only began a program of restoration and new building but also ended a century of lawlessness. One man could not undo a hundred years’ damage, however, and by the time of Martin’s death in 1431, Rome was still far from being a synonym for grandeur.

In this painting from the fourteenth century, the Catholic Church is surrounded by heretics

and unbelievers and defended by bishops, monks, and the pope. This depiction of a united

church contrasts sharply with the bloody feuds and protracted schisms that characterized the

papacy during the Middle Ages.

The New Caesars, a New Rome

During the fifteenth century, commemorative medals were cast bearing the moniker Roma caput mundi—“Rome, the world’s ruler.” This claim was hardly accurate, but the men guiding the church and the city believed it to be destiny, and they saw a revival of Rome as a city of beauty and power as crucial to this goal.

The Colosseum dominated Rome until the new St. Peter’s was built in the sixteenth century.

The pontiffs of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries also shared an ambition to recast the role of the papacy. Modeling themselves on the Caesars of the Roman Empire, the popes sought to present themselves as indomitable, magnificent rulers, their earthly grandeur reflecting their divine associations. Even in their personal lives, popes acted like kings and emperors, fathering illegitimate children, wrangling over money, feuding bitterly and bloodily, and enjoying lurid sexual adventures—all of which was fodder for delicious gossip, not for impassioned outrage, among the Roman public.

To impress their fellow Romans and visiting pilgrims with their imperial majesty, the popes embarked on a vast program of construction. Deteriorating churches bespoke papal weakness and decline, so all over Rome the churches of old were revisited and renovated as showcases of papal power. Meanwhile, in emulation of the Roman emperors who had built baths and civic parks to strengthen their support within the community, the popes began large civic building projects.

All these projects required building materials. Fortunately for papal ambitions, a ready supply was to be had right there in the heart of Rome: the ruins of the ancient empire.

The Renaissance popes did not intend to preserve the ruins. Indeed, they stripped them and destroyed many entirely. But in the process, they inadvertently saved some ancient buildings by consecrating them as churches, and they preserved many fragments of other imperial architecture by reusing them in new structures. And they achieved their main goal: to make Rome spectacular.

Over the course of a century, the popes transformed Rome from a medieval village into a Renaissance jewel. They widened streets and constructed hospitals. They transformed entire neighborhoods, such as the Piazza Navona, which once had been a thriving marketplace. The papacy claimed the area for churches and palaces.

Although the popes took the lead in restoring Rome, they were not alone. Wealthy families from across Italy returned to Rome; by the early 1500s, the city boasted a population of more than 50,000 people. These families poured their fortunes into the city, competing among themselves to build ever larger and more opulent houses. Once its home was built, a family would often then devote its riches and energies to building and decorating churches, whose beauty advertised not only the glory of God but also the family’s wealth and prestige.

Naturally enough in such an environment, artists found themselves in great demand—by the pope, by the cardinals, and by the upper classes. The demand was especially high as the fifteenth century drew to a close, because Pope Alexander VI had decided to name 1500 a year of jubilee and had called for pilgrims to come to Rome. The church recognized that the pilgrims coming to Rome en masse would expect pageantry and grandeur—and if they found what they were looking for, they would spend money, a lot of money. The potential to fill the papal coffers was great, and Alexander VI was keen to maximize that potential by putting on a good show.

Thus, when, on June 25, 1496, at the age of twenty-one, Michelangelo arrived in Rome, he found himself in exactly the right place at exactly the right time.

A New Home

Lorenzo de’ Medici once called Rome “the receptacle of all the evils imaginable, with no shortage of inciters and corrupters.” The city that greeted Michelangelo may have been in the process of beautification, but its political life was as ugly as ever. Cesare Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI (1492–1503), employed thugs and murderers to keep the city under his control. Prisons were full. Spies and assassins filled the streets. And Borgia extorted property from any aristocrat who dared to oppose him.

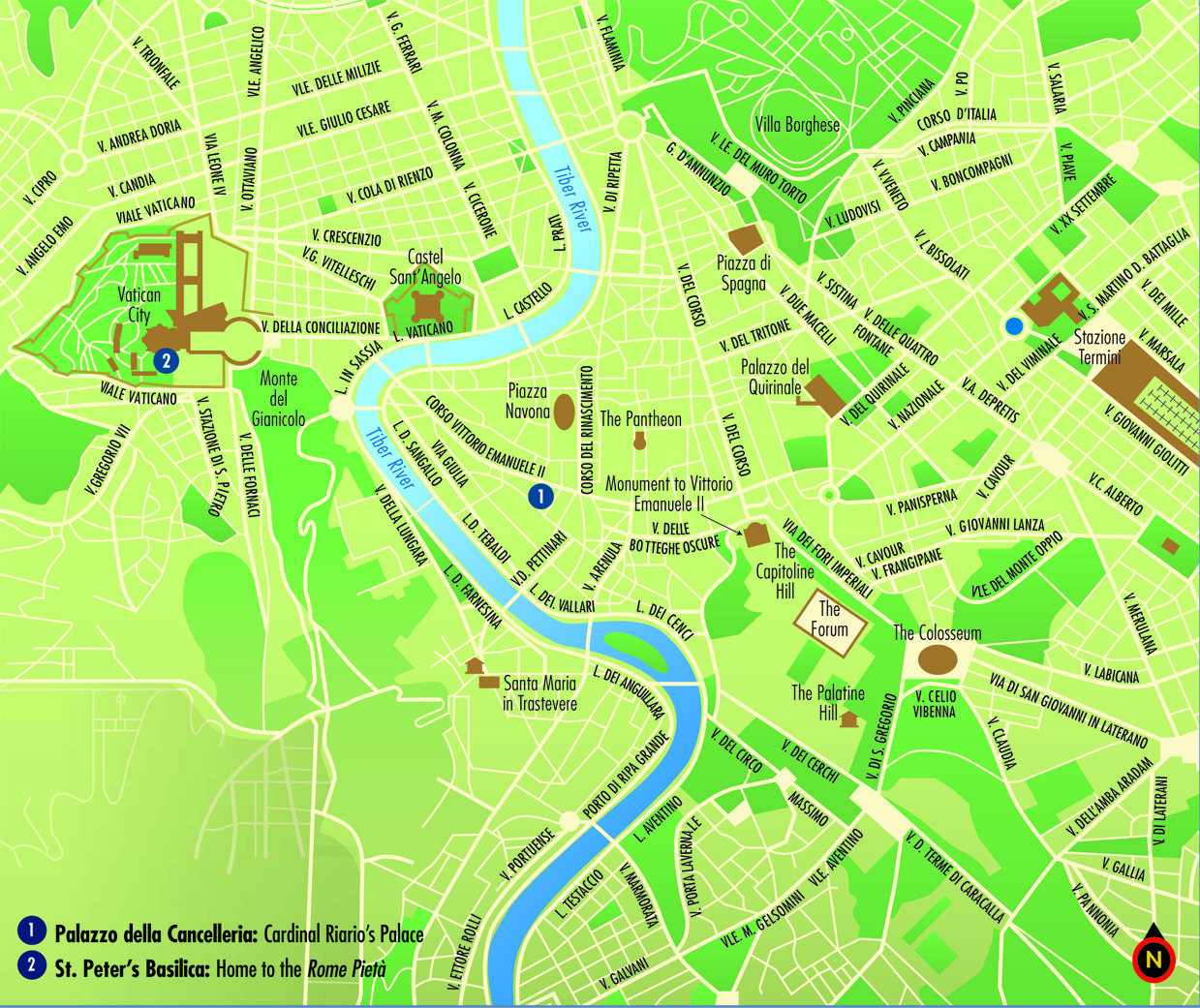

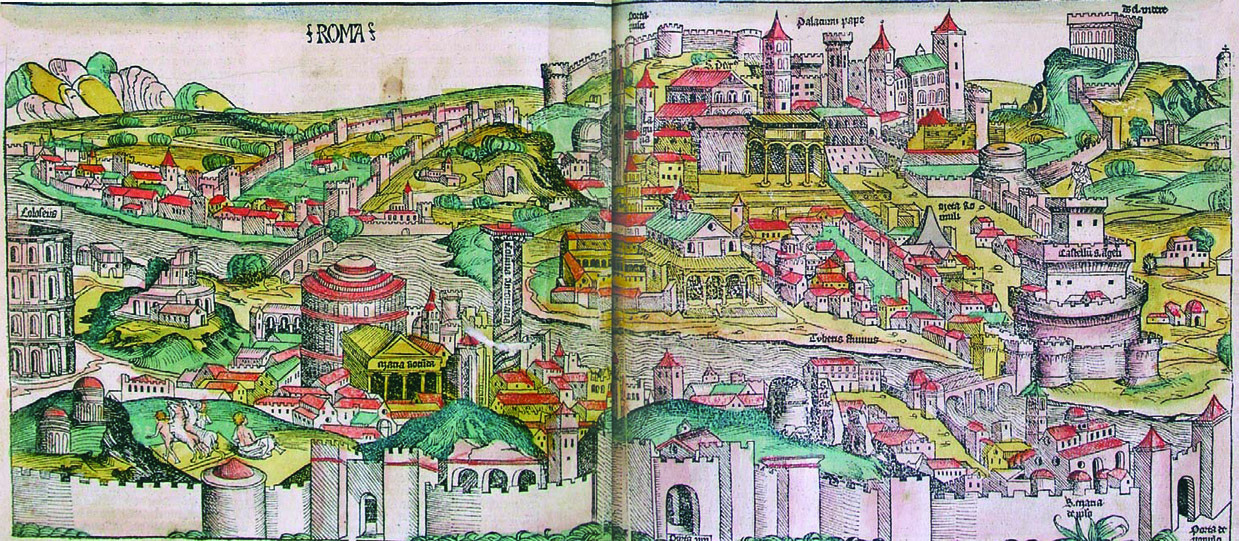

This map from 1493 shows a panoramic view of Rome from the Colosseum to

Castle Sant’ Angelo.

Having successfully navigated the misfortunes of the Medici, Michelangelo had learned to play the political games that would be necessary to win papal favor. He devoted himself to establishing his reputation during his first stay in Rome, which was to last nearly five years. This task would prove easier to accomplish than in Florence. In Rome, Michelangelo was out from under the shadow of the Florentine masters and closer to the heart of the Vatican—which had even more power and money than the Medici and the Borgia. In Florence, he had created half a dozen small sculptures, none of which had done much to bring him renown. In Rome, he set out to make a name for himself.

Michelangelo arrived bearing letters of introduction from Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici that paved the way for him to present himself to Cardinal Raffaele Riario, the richest and most powerful cardinal in Rome. The cardinal offered Michelangelo a place to stay within his household. With 250 people in his retinue, the cardinal had the means to take on the young man. He was also a great collector of antiquities.

This engraving of the Palazzo della Cancelleria was made by Giuseppe Vasi in the mid-1700s. In addition to being Michelangelo’s first home in

Rome, for centuries the palazzo housed the papal government that ran the city.

Cardinal Riario, the cardinal of St. George, was in the middle of building a new palace, now known as the 1 Palazzo della Cancelleria. Despite the ongoing construction, Michelangelo moved in. Sited in the middle of the Centro Storico—the historical center of the city—the Cancelleria gave Michelangelo easy access to the Pantheon, numerous churches, and the palazzi of the wealthiest Romans.

A week after he arrived, Michelangelo wrote to Lorenzo:

Popes during Michelangelo’s Lifetime

1471–84: Sixtus IV (Family: della Rovere) rebuilt the Sistine Chapel as a fortress and decorated it with frescoes he received as a gift from Lorenzo de’ Medici.

1484–92: Innocent VIII (Family: Cibò) played politics well. With strong ties to the Medici family, he built the Palazzo Belvedere at the Vatican. Originally a summer estate in the midst of meadows, the Palazzo Belvedere became the favored quarters for the popes and was eventually surrounded by the papal complex. It now houses some private rooms for the pope as well as part of the Vatican Museums.

1492–1503: Alexander VI (Family: Borgia), a ruthless pope, allowed his son, Cesare Borgia, to rule Rome with terror and cruelty.

1503: Pius III (Family: Piccolomini), may have been murdered to make way for his rival, Giuliano della Rovere.

1503–13: Julius II (Family: della Rovere) was Michelangelo’s first papal patron. He commissioned his own tomb and began construction on the new St. Peter’s Basilica. He also hired Michelangelo to fresco the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel..

1513–21: Leo X (Family: Medici) commissioned Michelangelo to create the façade of a small chapel inside Castel Sant’Angelo. He then sent Michelangelo back to Florence to work on the façade of San Lorenzo, the church where the Medici family worshipped.

1522–3: Adrian VI (Family: Boeyens) was the last non-Italian pope elected until Pope John Paul II in the twentieth century.

1523–34: Clement VII (Family: Medici) commissioned the Laurentian Library in Florence. Having escaped the Sack of Rome as a refugee, he eventually waded through a political morass and crowned Charles V, his one-time enemy, Holy Roman Emperor.

1534–9: Paul III (Family: Farnese) commissioned The Last Judgment as well as the Pauline Chapel and the Campidoglio. He also persuaded Michelangelo to take over the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica and to finish the Palazzo Farnese.

1550–5: Julius III (Family: del Monte) and Michelangelo developed a close relationship and Julius III insisted that Michelangelo continue as architect of St. Peter’s.

1555: Marcellus II (Family: Spannochi) was embarrassed by Michelangelo in front of Paul III when Marcellus was just a priest; the artist feared that as pope, Marcellus II would exact revenge. However, after only three weeks as pontiff, Marcellus II had a stroke and died.

1555–9: Paul IV (Family: Caraffa) considered destroying the Sistine Chapel and other “immodest” works of art.

1559–65: Pius IV (Family: Medici—the less-affluent Medici family in Milan) was Michelangelo’s last patron. He commissioned the Sforza Chapel, the Porta Pia, and Santa Maria degli Angeli in an effort to leave his mark on Rome.

Surrounded by the “very fine things” of Rome, Michelangelo immediately set to work on his first large-scale piece.

Bacchus

Renaissance artists believed that works of art should be imitations of nature. Nature itself was regarded as both a creative phenomenon and something that could be observed and documented scientifically. Making a work of art required the same blend of creativity and science. Some artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, the German engraver who was a contemporary of Michelangelo, even tried to distill art down to mathematical proportions and formulas.

Bacchus (1497).

Anatomically Correct

Michelangelo approached the study of anatomy as a means of achieving greater beauty in his figures. He had studied dissection at Santo Spirito in Florence from 1492 to 1494. “He was very intimate with the prior, from whom he received much kindness and who provided him both with a room and with corpses for the study of anatomy, than which nothing could have given him greater pleasure.” In his later years, though, Michelangelo had to give up dissection. Much to his chagrin, the stench of a decaying corpse made him ill.

The God of Wine

Bacchus, Michelangelo’s first work created in Rome, depicts the Roman god of wine. Bacchus (known to the Greeks as Dionysus) taught humankind how to cultivate grapes and make wine, and was—appropriately enough—the god of merriment and revelry. The great dramas of the ancient world were performed in honor of Bacchus.

During the Renaissance, Romans drank wine at every meal. Like ale and beer in Europe’s northern climes, wine in the south provided a safe, sterile drink that was far preferable to dirty river water. For a Roman, each day began with a small glass of wine, watered down slightly, and a piece of bread. People drank wine throughout the day as their primary beverage. Wine at breakfast may be out of fashion today, but pane e vino remains the foundation of the Roman diet.

Creating a lifelike image from flat plaster or solid marble certainly does require a solid understanding of mathematics, geometry, physics, and mechanics. In the quest for perfection, Renaissance artists fused art with science, seeking exact and accurate anatomy, proportions, scale, and perspective. Michelangelo mastered these rules and then learned to break them, taking sculpture beyond the achievements of the ancients. The artists of ancient Rome created lifelike forms from stone, but Michelangelo’s fusion of precision and spirituality helped him to create figures that seem almost to breathe.

With Bacchus (which today can be found in Florence’s Museo Nazionale del Bargello), Michelangelo learned to use the drill—a tool ancient Romans employed with great skill to create illusions that cannot be produced with chisels. While he tried out new techniques, Michelangelo also played with composition. Bacchus, as his blank gaze, unsteady posture, and precarious goblet of wine all attest, is drunk. The English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley later remarked that the figure “looks drunken, brutal, and narrow-minded, and has an expression of dissoluteness the most revolting.”

Dirty Work

Marble comes from limestone and is of medium hardness. It is often chosen for sculpture because it can be polished to a high shine and because, through it, a sculptor can achieve remarkable levels of detail. But it is difficult to work with, as Leonardo da Vinci made clear:

The contract between a patron and a sculptor usually stipulated the type of material to be used in a commissioned piece, the source of the material, the finish to be used, and the deadline for completion. A sculptor had to know his materials well when investing time and money in a block of stone. He had to consider the workability of the stone, its color, its durability, the size of the block needed, and how to transport it to his workshop, which was typically hundreds of miles from where the rock was quarried.

Sacred Sculpture

Sculpture as an art form went out of fashion with the rise of the early Christian church. The church founders considered the sculptures of the ancient Romans to be idols and demons, and the sculpting of freestanding forms eventually became taboo. Yet, human and animal figures persisted in church and domestic decoration in the form of relief and architectural elements. When, around 1440, the Florentine sculptor Donatello unveiled his David, a new artistic era began.

Donatello’s bronze was not only the first freestanding figure of the Renaissance but also a nude. Emboldened by his example, sculptors began to imitate classical figures that could still be found throughout Italy.

For Michelangelo, the ideal sculpture emerged from a single block of marble, which meant he had to be especially careful in choosing his stone. Like many sculptors, he often visited the quarries in Pietrasanta and Carrara in Tuscany, where marble has been quarried since the first century A.D. To make sure he could get the finest stone, Michelangelo cultivated close relationships with quarry workers, compensating them generously. In return, they labored loyally and diligently on his behalf in a perilous line of work. The sculptor himself was nearly killed one day in a quarry when a ring supporting the ropes around a large block of marble snapped, sending the rock hurtling downhill toward him.

To quarry marble, Renaissance workers inserted a series of wooden wedges into cracks in the stone. When they poured water over the wedges, the wedges swelled. The process was repeated over and over again until the block split away from the mountain. The stones were then given a “rough dressing”—shaped into usable blocks—before being shipped away.

The tools of a sculptor have hardly changed since Michelangelo’s day.

A Sonnet by Michelangelo (undated)

Once stone arrived in his workshop, Michelangelo used large chisels and drills to remove the bulk of the stone, gradually transitioning to finer chisels for the detailed work. He used both small and full-sized models based on his sketches to guide his work. Made from clay, the models were supported by a wooden armature. If the figure was to be clothed, the model could be draped in cloth dipped in clay to give it beautiful, flowing, but permanent folds of voluminous cloth.

Michelangelo worked on full-scale figures in the same way that he did relief: from the front to the back. He would make a wax model of the figure and lay it in a pan of water. Then, as he worked back through the marble, he raised more and more of it from the water, revealing the figure a bit at a time.

He did not “finish” every inch of his pieces; rather, he left parts of each sculpture in rough rock, a testament to their origins and to his love of stone in its raw form. The proportions of the original marble block can be gauged from the size of the base of each piece. The finishing process—and the sculpting process itself—was dirty and dangerous, much like quarrying. As he hammered against his chisels, metal on metal against stone, chips flew. He did not wear safety glasses. The hammers and chisels and stones were heavy and bulky and sharp. Sculpting was bruising, sweaty work—but it was also inspiring for Michelangelo, who not only wrote poems about sculpting but also while sculpting.

To light his workshop, Michelangelo spent money on expensive candles made of pure goat’s tallow. He often worked into the night, carving and polishing in the candles’ golden glow. He constructed a “helmet made of pasteboard holding a burning candle over the middle of his head which shed light where he was working without tying up his hands,” a biographer noted. Michelangelo used light—both natural and candlelight—to guide him as he created different textures: cloth, skin, hair, wood—each with its own sheen and depth. He often worked on several pieces at once. He carved constantly, taking pleasure and solace in his work.

The Rome Pietà

Cardinal Riario may have invited Michelangelo to join his entourage, but he did not like what Michelangelo produced from that first block of marble. So the young man found another buyer for Bacchus, Jacopo Galli, a wealthy collector of antiquities. Galli then worked on Michelangelo’s behalf to help him find his next commission. It came from a powerful French cardinal, Jean Bilhères, who wanted Michelangelo to create a grave marker for himself to be placed in St. Peter’s Basilica. The contract, signed by GalliO and Michelangelo, read: “I Jacopo Galli promise the Reverend Monsignor that the said Michelangelo will do the said work in a year and it will be the most beautiful marble which can be seen in Rome today, and that no other master could make it better today.”

The Rome Pietà (1499). A pietà is a traditional Christian composition featuring Mary mourning over the

crucified body of her son. Michelangelo carved three pietàs during his lifetime. His first is known as the

Rome Pietà because of its location. The other two are the Rondanini Pietà, which can be found in Milan’s

Castello Sforzesco, and the Florentine Pietà, which is in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence.

Michelangelo’s David (1504) is known by Florentines as Il Gigante, the

giant. Moving it from his workshop to its first public location in the

Piazza della Signoria took several days. In its original spot, David stood

guarding the entrance to the seat of Florence’s government as a symbol

of civic pride and virtue. In 1874, the sculpture was moved to the Galleria

dell’Accademia; a replica remains in the Piazza della Signoria.

Michelangelo traveled to Carrara to choose a large piece of high-quality marble for the work. The contract called for a sculpture of Mary holding the crucified Jesus. The composition Michelangelo created involved carving two full-sized figures from one block of marble—a difficult task. Michelangelo bent the rules of proportion to his own purposes: Mary is much larger than Jesus to support the weight of a life-sized figure in her lap, but their heads are the same size, making the difference in size hard to detect. Mary’s size serves a structural purpose, but it also allows the grieving mother to hold her son on her lap, creating a tableau that is both powerful and tender.

The Rome Pietà—as it is now known—was installed in St. Peter’s and was immediately acclaimed as a work of supreme beauty and skill. But as he stood in the basilica one day, Michelangelo overheard someone attribute the piece to Gobbo, a sculptor from Milan. Michelangelo grabbed his tools and returned to add one final touch to the piece: his signature on the sash across Mary’s chest. It was the only piece he ever signed.

Today the Rome Pietà occupies a side chapel in 2 St. Peter’s Basilica, separated from viewers by thick panes of bulletproof glass installed after a vandal attacked the piece with a hammer in 1972. Before St. Peter’s was rebuilt, the sculpture sat on the floor above a tomb. Today it is displayed on a pedestal in a secluded chapel, which prevents it from being seen at its best angle. Some experts believe that if it were moved to a dark church, the lighting would shift the focus away from Mary and on to Christ.

Michelangelo’s Rome Pietà was recognized as extraordinary for its emotional depth, as well as for its technical mastery, and the artist’s reputation rapidly grew. He had achieved his goal: in his five years in Rome, he had established himself as a sculptor in demand.

When reports of Michelangelo’s success reached Florence, his father was both pleased and upset: pleased because his son was evidently on the threshold of a lucrative career, upset because as long as his son remained in Rome, he, the father, would have a difficult time grabbing a slice of his son’s wealth. He wrote to Michelangelo, pressing him for money and urging him to return to Florence. Answering his father’s call, Michelangelo left Rome—but only for a short time.

Return to Florence

Politically, Florence was calmer than when Michelangelo had left. Savonarola had met his fate: hanged publicly, his corpse was burned like so many of the artworks he had destroyed. The French controlled the city, having been allowed to enter by Piero de’ Medici in 1494, but relative peace had returned, allowing the inhabitants to get back to work and the wealthy to hire artists again.

Michelangelo returned to Florence a successful artist, and soon received well-paid commissions from a range of patrons, some quite powerful, in his native city. One commission would further enhance and forever cement his reputation as a great sculptor: David. The block of marble from which David was carved had been quarried nearly half a century before. Two other artists had attempted to work with it but had found it too huge and flawed. The block had lain abandoned for years.

SPQR

The empire may have dissolved after Rome was sacked by the Visigoths in 410A.D., but the spirit of the empire never died. Modern Rome bears the stamp of ancient Rome in places both pedestrian and noble. Everywhere, from lampposts and trashcans to pope’s tombs and T-shirts, the letters SPQR invoke the spirit in which the city was founded: Senatus Populusque Romanus, meaning “the Senate and the people of Rome.”

Nearly seventeen feet tall, Michelangelo’s sculpture portrays the biblical King David as a powerful, muscular young man gazing intently at his unseen target, Goliath, just before loading his slingshot. His physique and stance suggest an ancient Apollo—godlike and idealized. Completed and installed in 1504, the piece made Michelangelo famous throughout Italy.

The achievement brought him to the attention of the new pope, Julius II, who had been elected by the cardinals in 1503. Julius wanted an elaborate tomb for himself, and he decided to entrust the task to Italy’s new star. Michelangelo eagerly accepted the commission and promptly returned to Rome to start work. However, Julius’s tomb would take far longer to complete than anyone could have imagined.