Chapter 4

San Pietro in Vincoli

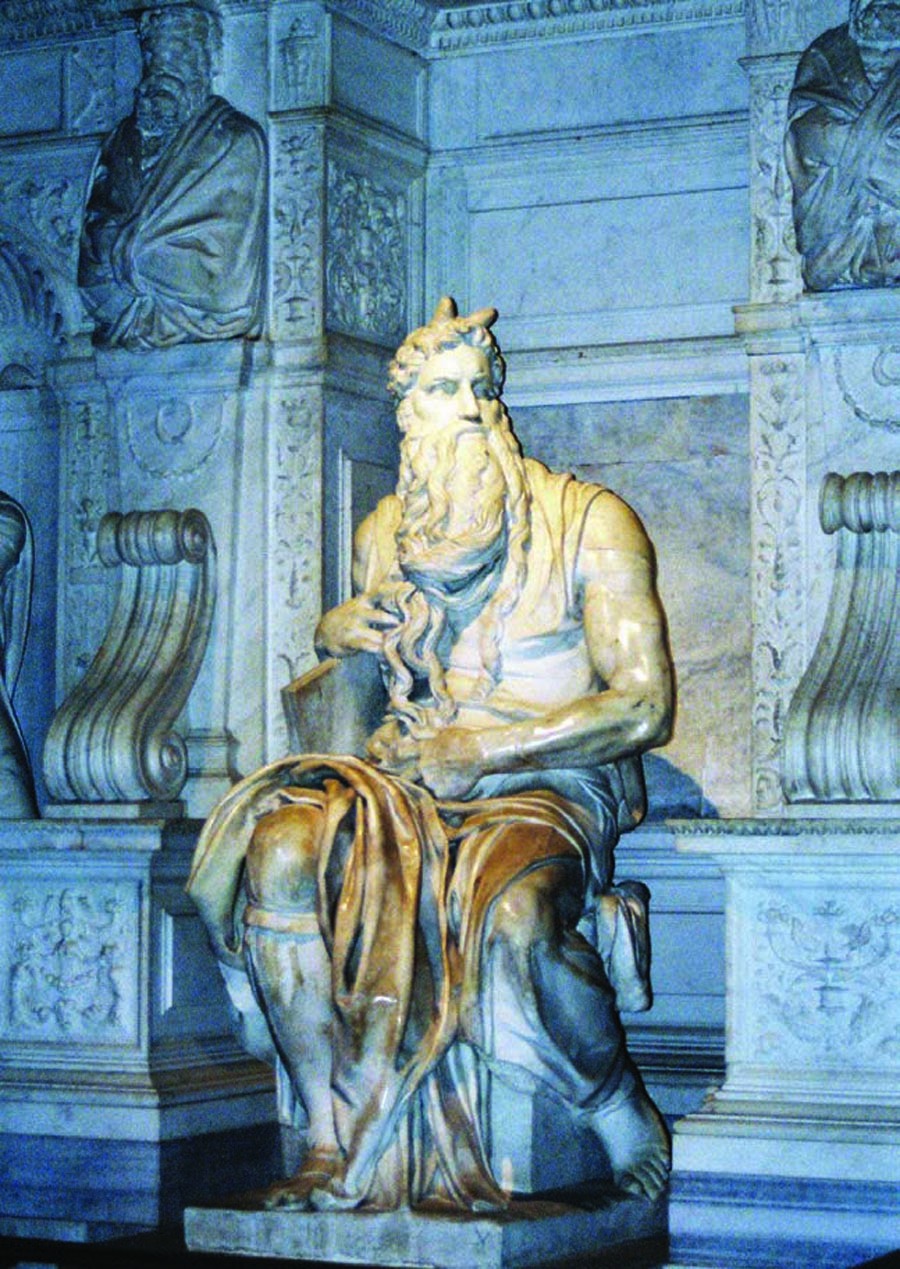

Pope Julius II’s tomb took years to complete,

but Michelangelo considered Moses (center)

to be his most significant accomplishment.

With the papal summons to Rome, young Michelangelo was officially being celebrated across the peninsula as a genius. The Rome Pietà had cemented his reputation in Rome. David had established him as a great artist in Florence. And now the pope wanted his services. Michelangelo had finally arrived: he had secured a patron with power, influence, and deep pockets.

An impatient man, Michelangelo was frustrated that the pope did not summon him for an audience as soon as he arrived in Rome. But Julius II was carefully considering how to use the artist. Michelangelo waited many months in Rome before the pope decided on his commission. In April 1505, Michelangelo and the pope signed a contract for 10,000 ducats in exchange for a monumental tomb for the pope.

Julius II’s tomb was to be enormous, enough work for a lifetime. The tomb reflected the ambition and arrogance of both the pope and the sculptor—traits that bonded the two but that also set them at odds.

The tomb was originally to be installed in San Pietro in Vincoli, the church where Julius II had served before becoming pope. But as the plans expanded, the pope had a better idea for the tomb’s placement: St. Peter’s Basilica. When Michelangelo surveyed St. Peter’s, though, he determined that the tomb that he had designed would not fit. Rather than scale back his ambitions, he suggested that the church be expanded. Julius II agreed and ordered designs for a renovated St. Peter’s to be prepared. Michelangelo was given an advance of one hundred gold florins, the equivalent of a year’s pay, and the pope’s blessing to travel to Carrara to choose the marble for the tomb. Michelangelo left almost immediately, spending eight months selecting stone with which to begin the project.

Feared, Hated, and Respected

In Julius II, pope from 1503 to 1513, Michelangelo found an influential friend and a frustrating adversary. The most powerful of the Renaissance popes, Julius II came from the wealthy della Rovere family. In 1503, he was a youthful sixty-year-old man with energy, ideas, and enthusiasm. He hated the French, loved war, and wanted to establish the papacy as a powerful force independent of the Roman families who tried to interfere in papal politics. Some feared him, others hated him, and all respected him.

Michelangelo and Julius II in a painting by Anastagio Fontebuori.

By the time he summoned Michelangelo, the ambitious pope had lived in the Eternal City since 1471 and despaired over its state of decay. Cows grazed in the buildings and temples of the Forum. Peasants tended their vineyards on the Palatine Hill, wandering through palatial remains. The Circus Maximus hosted gardeners tending their plots rather than drawing crowds for chariot races. Raw sewage stank in the streets, and the Tiber reeked with refuse. The city known as the world’s capital looked and smelled like the remains of an ancient festival long forgotten.

With full coffers and political savvy, Julius II aimed to continue Pope Martin V’s work in turning the dirty, run-down city into a beacon of Christianity, but he had larger diplomatic goals, too. He wanted to regain the church’s autonomy and to get out from under the influence of foreign kings and emperors. His war cry became, “Out with the barbarians!” He recognized Rome’s importance as the center of a faded empire and its potential to become a gleaming symbol of a reinvigorated Catholic Church—a capital to rival London or Paris.

Lined with shops and restaurants, fashionable Via Giulia lies in the center of the bustling

city. To build it, Julius II demolished existing homes and shops, hoping to create a city of

straight, wide boulevards.

Julius decided to begin with the papal palace and the behemoth St. Peter’s, but his program of improvement grew during his ten years as pope to include bridges, villas, piazzas, and, ultimately, a historic redesign of the city complete with boulevards and civic monuments. To get a feel for Julius II’s vision of Rome, a visitor might walk Via Giulia, the straightest street in the city. Julius II demolished countless buildings to make way for a wide, straight path from the Ponte Principe Amedeo along the river. Here, charming buildings line a street largely unchanged since the sixteenth century. Among those buildings is the 1 church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, which sports a dome designed by Carlo Maderno, who was influenced by Michelangelo’s dome for St. Peter’s Basilica. Pets are welcome at the church, and well-behaved cats and dogs often attend services.

Monumental Influences

Great cities celebrate their great leaders, and as the self-appointed director of Rome’s rebirth, Julius II wanted to celebrate himself. Born Giuliano della Rovere, he chose as his papal name the name of one of Rome’s great emperors, and he wanted to be memorialized in the grandest Roman style. Thus, he chose the finest sculptor in Italy to construct what was to be the largest tomb in Rome since the days of the Empire.

Gregory the Great renamed Hadrian’s Mausoleum Castel Sant’Angelo in the sixth century. Rome was suffering from the plague, and Pope

Gregory had a vision of St. Michael on the mausoleum, which he interpreted to mean that the plague was over. Eventually, the Vatican converted

Castel Sant’Angelo from a mausoleum into a fortress, and then into a castle connected to the papal quarters via a fortified passageway.

Roman emperors, like the popes after them, often began building their tombs as soon as they came to power. The tombs represented power, greatness, and eternity. They dot the city of Rome today—some still standing as tombs, others requisitioned for different purposes. As Julius II looked to the past for a precedent, he had only to look out his window: 2 Castel Sant’Angelo began as Hadrian’s Mausoleum.

Built during the second century A.D., Hadrian’s Mausoleum was used as the emperors’ burial place for almost a century. The structure was originally covered in marble and travertine, topped with a mound of earth planted with trees, surrounded by statues, and crowned with a statue of Hadrian and a four-horse chariot.

In the Middle Ages, the mausoleum was transformed into a fortress and altered significantly to become the Vatican’s stronghold, prison, and, for a time, treasury. The statue of Hadrian, removed long ago, was replaced by an angel, hence the name Castel Sant’Angelo. Now a museum, Castel Sant’Angelo offers a delightful view of the city as well as a café at the top of the structure.

To access the mausoleum from the city center, Hadrian built the Aelian Bridge, now known as the Ponte Sant’Angelo, across the Tiber. Today the Ponte Sant’Angelo features figures of angels designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680).

A Leonine Façade

Pope Leo X (pope from 1513 to 1521), the successor to Pope Julius II and a Medici, was eager to put Michelangelo to work for him as well, but he allowed the artist to return to Florence to work for the Medici there. Before he left Rome in 1515, though, Michelangelo designed the façade for a small chapel in the Castel Sant’Angelo. The façade anchors a wall with a graceful and elegant simplicity, beautifying an otherwise unremarkable courtyard. The lion heads are a play on Leo’s name; his symbols—a ring and feathers—cap the composition, incorporating the papal signature. The marble for the project probably came from the stores procured for Julius II’s tomb.

Below the chapel lie dungeons, reminders that Castel Sant’Angelo served as Rome’s prison during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Like other grandiose

mausoleums in ancient Rome,

the Mausoleum of Augustus

was not only a monument to

the dead but a gathering

place for the living. Today,

only parts of the original

building remain. Augustus (27

B.C.–14A.D.) and his family

were buried here; over the

centuries, it was used for a

variety of purposes including

as a fortress.

Hadrian was not the first to build a monumental burial ground. Up the river from Hadrian’s Mausoleum lies the 3 Mausoleum of Augustus. Augustus began his mausoleum in 29B.C. after seeing Alexander the Great’s tomb in Alexandria, Egypt. Although it has now been stripped of much of its grandeur, it was an imposing monument in its time. It, too, was topped with trees and two levels of garden areas. Two obelisks flanked the doors; both were removed during the building craze of the Renaissance. Romans have used the Mausoleum of Augustus in a variety of ways, including as a venue for public gatherings and shows. During Mussolini’s reign, excavations cleared away additions made over the centuries to reveal what remains of the original structure.

The original design for Julius II’s tomb incorporated ideas from not only the imperial mausoleums but also the triumphal arches of imperial Rome. The ancient Romans marked events of historic significance—often victory in battle—by erecting imposing arches. Public monuments extolling virtue and valor, the arches celebrated the might of the Roman Empire.

Julius II and Michelangelo probably looked to the 4 Arch of Constantine as a model. Erected as part of a celebration of the tenth year of the emperor’s reign (315A.D.), the arch commemorates Constantine’s military and civic accomplishments. Its creators poached reliefs from other Roman edifices to complete it quickly.

When Michelangelo walked to the Arch of Constantine, however, he wouldn’t have been able to see it in its entirety. The city had engulfed the monument, burying more than half of it under dirt and debris and surrounding it with homes and businesses. The arch, like Augustus’s Mausoleum, was not completely excavated until the twentieth century.

The Arch of Constantine.

Both the pope and the sculptor almost certainly devoted a lot of attention to the 5 Arch of Janus, which in size and scale closely resembles the monument Julius planned for himself. Located steps away from the church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin and its famous marble disk called the Mouth of Truth (an ancient drain cover that, according to legend, bites the hand of a liar), the Arch of Janus was erected in 357A.D. to celebrate the Roman god of beginnings and endings.

Although the original design for Julius II’s tomb does not survive, documents from the time indicate that the freestanding structure was to measure twenty-three feet long by thirty-six feet wide and was to be as high as it was long: roughly the size of the Arch of Janus. It was to be dominated by four main figures and topped with a larger-than-life-size sculpture of Julius II himself.

The tomb was intended to portray Julius II as a patron of learning and the liberal arts. More than forty carved figures were to anthropomorphize the fine arts, including grammar, rhetoric, arithmetic, logic, music, astronomy, geometry, painting, sculpture, and architecture. In addition, angels were to flit about the structure, and bronze reliefs were to illustrate scenes from Julius II’s life.

The Arch of Janus.

Conflict

Michelangelo returned to Rome from Carrara in the winter of 1506. Before he left the city the previous spring, he secured a studio where he could live and work. His house stood on Piazza Rusticucci, a humble, quiet piazza with a simple little church, Santa Caterina delle Cavallerotte. The studio, the piazza, and the church are no longer there; tourist shops and Vatican offices now dominate the area, which lies between Piazza San Pietro and Via della Conciliazione.

Michelangelo, who had stopped to visit his family in Florence on his way home, found when he arrived in Rome that the marble had preceded him and was waiting at the port. He had the blocks transported to the 6 Piazza San Pietro. The Italian piazza, like the town square in the United States or the place in France, is where society gathers. To place marble in the piazza, then, was to invite inspection, conversation, and admiration.

In the meantime, the pope had decided he needed better access to Michelangelo’s studio; fortunately, he found an easy solution. Centuries earlier, a fortified passageway had been built between the Vatican and Castel Sant’Angelo to enable popes to be whisked away when in danger. From the 7 Passetto (which means “corridor”), Julius II built a drawbridge to Michelangelo’s studio. This way he could secretly visit Michelangelo without having to walk across the public piazza. Among its other advantages, such a discreet route meant that other artists, such as Bramante, would not be aware—and thus would not be jealous—of the time and attention Julius II lavished on the sculptor.

Purchasing the mountain of marble—more than ninety wagonloads—from Carrara and moving it to Rome cost a great sum. Michelangelo paid for the expenses from his own coffers. Julius II had insisted that Michelangelo come to him personally in matters of finance, so a few days after settling into his house on Piazza Rusticucci, Michelangelo walked the short distance to the papal palace to collect on his expenses.

Michelangelo explained in a letter to his friend Giuliano da Sangallo what happened next:

Christian Burials in Ancient Rome

During the first and second centuries A.D., the bodies of Roman emperors and common citizens were typically cremated. The law forbade cremation and burials within city walls, so crematoriums were built outside the city. Some Romans, however, buried their dead. Wealthy families often owned mausoleums where they buried their ancestors in sarcophagi or placed their ashes in urns. On holidays and during certain celebrations, families ventured out to their mausoleums to make offerings of wine, olive oil, and bread to their ancestors.

Christians were especially likely to opt for burial—and for a very practical reason: they believed in an imminent resurrection, for which they would need their bodies. Bodies of those not wealthy enough to have a mausoleum were buried in catacombs. The soil in many places in Rome is such that when exposed to air, it hardens into stone, which is perfect for carving out tunnels lined with burial chambers. Families were required to purchase clay seals for each tomb—signed and dated indications that the burial taxes had been paid.

Modern misconceptions hold that Christians chose the catacombs as places to bury their dead out of fear of persecution. Although persecution was certainly a reality, the catacombs were sanctioned—indeed, taxable—places for burial. Christian churches and gathering places did, however, crop up around the catacombs, because the burial grounds held the remains of saints.

When he returned on Saturday, the doorman refused him entry:

Barred from Julius II’s presence and denied the money he was owed, Michelangelo replied, “And you may tell the pope that from now on, if he wants me, he can look for me elsewhere.” Michelangelo returned to his studio. His pride injured, and tired of papal politics, he and his servants sold all his furniture, packed their belongings, and set out for Florence in April 1506.

This undated sketch by Michelangelo shows part of an early design for Julius II’s tomb. It is interesting to note

that the actions and poses of the angels and cherubs in this sketch are mirrored in the nudes in the Sistine

Chapel ceiling.

Despite his reluctance to pay Michelangelo, Julius II did not want to stall progress on his tomb. He sent five couriers to follow Michelangelo and his retinue; they caught up to the travelers outside of Rome. The letter the couriers bore commanded Michelangelo to return Rome at once. Michelangelo replied that “he would never go back; that in return for his good and faithful service he did not deserve to be driven from the pope’s presence like a villain; and that, since His Holiness no longer wished to pursue the tomb, he was freed from his obligation and did not wish to commit himself to anything else.”

Sending the couriers on their way, Michelangelo hurried to Florence. The couriers knew that they faced the wrath of the pope if they returned without Michelangelo. The sculptor had offered to lie to the pope, saying they had found him in Florence, beyond papal jurisdiction.

Julius II’s refusal to pay Michelangelo reflected a change in papal finances and priorities. While Michelangelo had been in Carrara, Julius II’s focus had shifted. As Michelangelo had recommended, the pope had commissioned designs to rebuild St. Peter’s to accommodate his tomb, and a design by Bramante had been chosen. But the new plan called for an enormous building that would require commensurate funding. Julius II saw this as an opportunity to build not just a monumental tomb but also a monumental church as part of his legacy in Rome—but he needed funds to make his vision a reality. The Papal States were an obvious source of funding for projects through taxes and trade, but papal control over those territories had weakened during the previous century. Thus, the pope set off with an army of mercenaries to bring the Papal States back in line and refill the depleted coffers.

Macel de’ Corvi

Michelangelo’s house at 8 Macel de’ Corvi sat across from the church of Santa Maria di Loreto. The artist lived here on and off after Julius II’s death in 1513. The house proved to be a point of contention in the forty-year struggle between Michelangelo and Julius II’s heirs to complete the tomb. A simple but ample dwelling, it boasted high ceilings, a garden, and a grand staircase. Over the staircase, Michelangelo painted a skeleton with a coffin—perhaps an example of his dark sense of humor.

After his death, the house remained standing until 1875, when it was demolished along with many other buildings in the area to make way for the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II (1820–78), the last king of Piedmont-Sardinia and the first king of the united Italy. The façade was saved, however, and in 1941 it was moved to the 9 Janiculum Hi ll and installed on the front of a building housing a water reservoir.

Macel de’ Corvi was part of Michelangelo’s compensation for Julius II’s tomb. Macel

de’ Corvi, or Slaughterhouse of the Crows, is actually the name of the neighborhood

where the original house stood. The façade of Michelangleo’s house is now on the

Janiculum Hill.

While the pope was off making war, however, he did not forget about Michelangelo, who had settled down in Florence. Letters from Julius II demanding Michelangelo’s presence in Rome arrived regularly. Piero Soderini, the gonfaloniere of Florence, finally intervened. Fearing that Julius II would bring his military campaign to Florence in pursuit of the artist, Soderini sent Michelangelo to Bologna, where Julius II had just declared victory.

“No sooner had [Michelangelo] pulled off his boots,” recorded Vasari,

San Pietro in Vincoli, home to Julius II’s tomb, is an unimposing but charming basilica that is rarely crowded

even though it is home to what Michelangelo considered his greatest sculpture.

A bishop in attendance tried to help Michelangelo’s cause, “declaring to His Holiness that such men were ignorant and worthless in anything outside of their art.” Julius II flew into a rage, beating the bishop with his mace and screaming, “You are the ignorant one, speaking insults We would never utter!”

With that, Michelangelo and Julius II settled into a peaceful patronage. The pope commissioned a bronze statue of himself to be placed above the door of San Petronio in Bologna. Michelangelo set to work on the statue. In preliminary models, he depicted Julius holding a book in his hand. The pope scoffed, “I know nothing about literature!” Michelangelo put a sword in his hand instead. A few years later, the bronze of Julius was melted down by the people of Bologna in an act of defiant revenge. Not even a sketch of it survives.

Changing Times

exist to keep the dead alive in the memories of the living. When Julius II died in 1513, the plans for his tomb were immediately scaled back. The original plan would have consumed a sizable fortune, with which his heirs were not willing to part. And the election of Leo X after Julius II’s death ensured that the tomb project would not continue according to the original plan, for Leo X hailed from the Medici family and would not allow a della Rovere pope’s tomb to dominate the St. Peter’s structure now under his control.

For more than thirty years, Julius II’s tomb haunted Michelangelo. It became a political pawn for powerful families and a personal crusade for the artist, who at times found his reputation impugned by the other players in the drama. In 1542, Michelangelo wrote to a member of the College of Cardinals, “I say and affirm that either for damages or interest five thousand ducats is due me from the heirs of Pope Julius; and in the meantime those who have taken all youth and honor and property from me call me a thief!” That same year, Michelangelo entered into the last contract for the tomb. This final contract stipulated not only a much less ambitious design but also a less prominent location—not in St. Peter’s but in 10 San Pietro in Vincoli. This modest basilica north of the Colosseum had been Julius II’s cardinal seat. Called “St. Peter in Chains,” the church houses two sets of chains. Reputedly, these chains held Peter while he was in jail in Jerusalem and when he was imprisoned in Rome. The two are said to have fused together miraculously; they can now be seen in the confessional beneath the high altar.

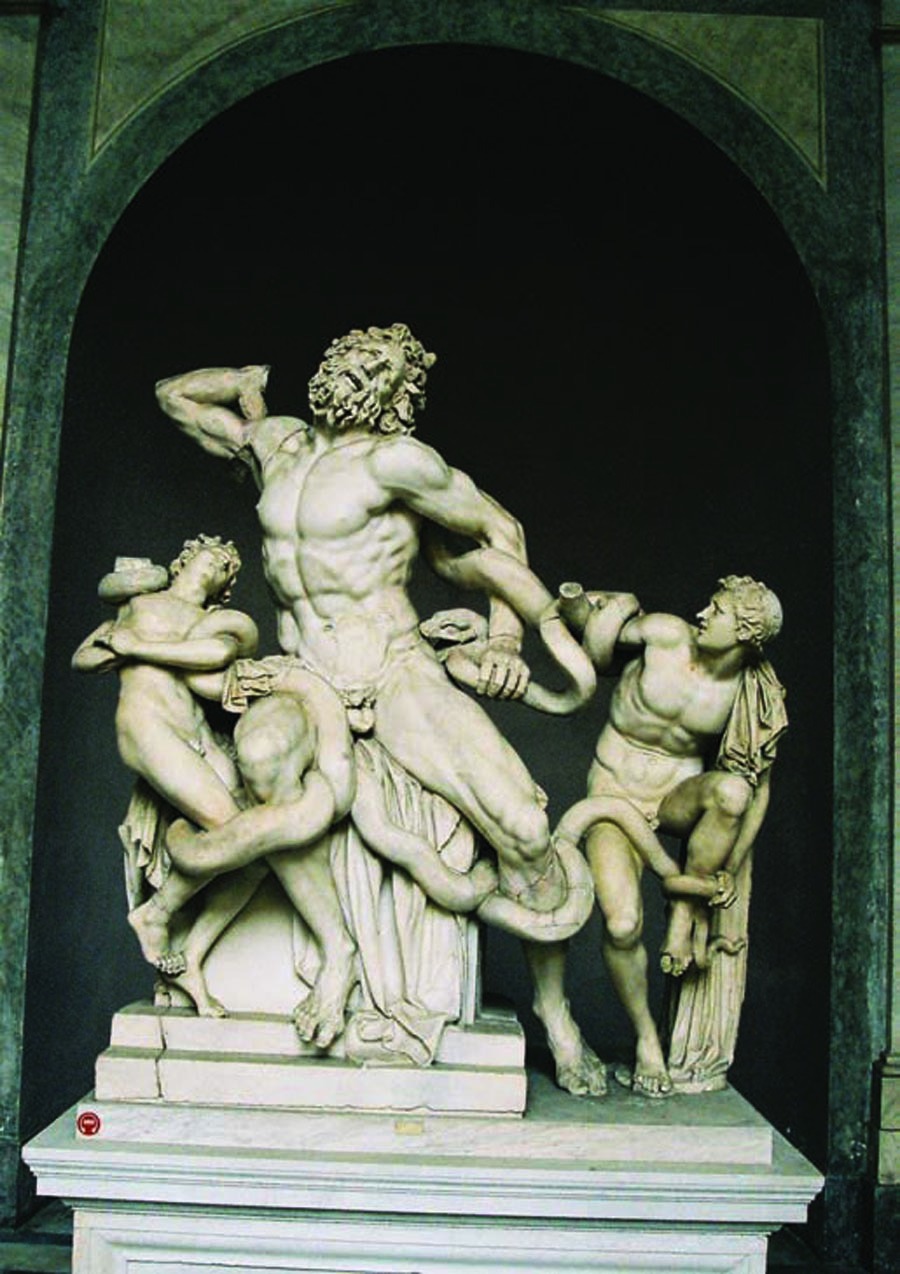

Laocoön

In January 1506, word spread of a tremendous sculpture discovered in a vineyard near Santa Maria Maggiore. Julius II sent a servant and Michelangelo to see what was happening, and so it was that Michelangelo witnessed the excavation of the most famous discovery of his day: Laocoön, exhumed from the Sette Sale of the Domus Aurea.

According to legend, Laocoön, a priest, angered the gods. During the Trojan war, he warned his fellow Trojans of the danger in accepting the wooden horse from the Greeks, but to no avail. At the behest of the gods, snakes came from the sea, snatched Laocoön and his sons, and dragged them to a watery death.

Depicting Laocoön and his two sons in mortal struggle with writhing serpents, Laocoön had been buried for centuries. Julius II bought the sculpture and placed it in the Belvedere Courtyard for artists to study and admire. As Michelangelo planned Pope Julius II’s tomb, he undoubtedly drew inspiration from the muscled angst of the ancient sculpture. Laocoön now resides in the 11 Vatican Museums.

Laocoön.

In Bondage to This Tomb

Although Julius II’s tomb is remarkable, Michelangelo described the finished work as “the tragedy of the tomb”: “I find I have lost all my youth bound to this tomb,” he wrote.

According to legend, Michelangelo found Moses to be so lifelike that he once struck the

sculpture’s knee and called out, “Speak, damn you!”

For decades, Michelangelo had worked on figures for Julius II’s tomb, often in secret so that his other patrons would not know of his divided attention. The figure he completed first was Moses. A cardinal who had come to Michelangelo’s studio to see another project said upon seeing Moses, “This statue alone is sufficient to do honor to the tomb of Pope Julius.”

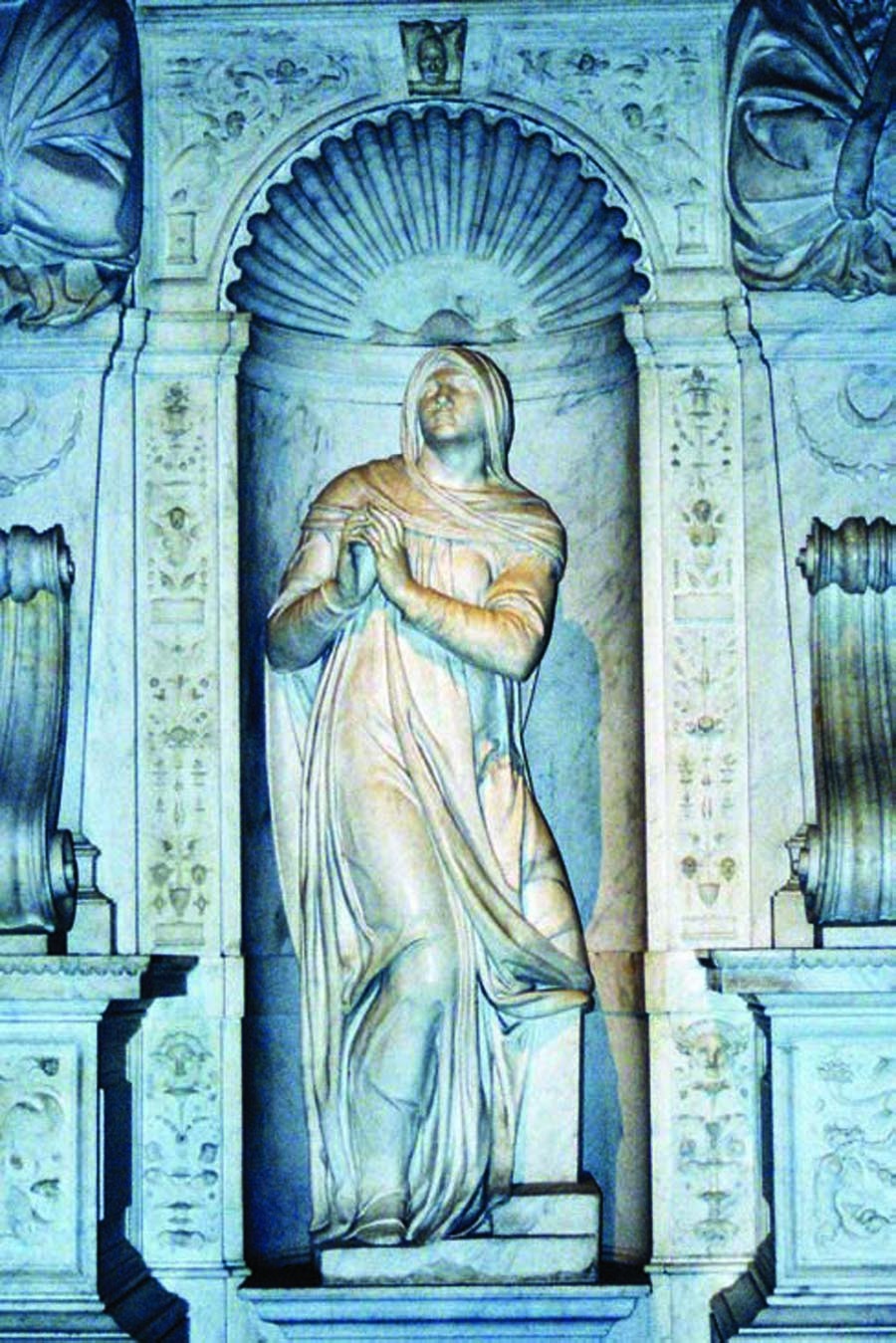

Leah.

Moses illustrates Michelangelo’s brilliance as a sculptor. At the moment depicted, Moses has just descended from Mount Sinai, having seen God and been given the law on the stone tablets under his arm. The Old. Testament describes him as glowing in the “radiance of the Lord,” but a medieval translator mistakenly rendered the phrase as having horns, so Michelangelo presents Moses with satyr’s horns protruding from his forehead. The figure’s torso is disproportionately long (he would be ten feet tall if he stood up) to give him power and presence; this trick is concealed from the viewer by Moses’s muscular arms and flowing beard.

Slaves

Originally destined for Julius II’s tomb, six slave figures, two of which were made in Rome and four in Florence, show Michelangelo’s mastery of expressive form and vividly display his carving techniques. Their contrasting poses offer an impressive range of expression, from the languid Dying Slave to the taut Block-Head Slave.

Some scholars contend that the slaves (or “captives,” as they are also known) are unfinished works, with much of the stone still rough and unpolished or shaped. Whether Michelangelo would have agreed with these scholars is questionable. The fragments and ruins of imperial Rome fueled his imagination precisely because they were incomplete. In Michelangelo’s mind, the unfinished conveyed the essence of and the idea behind a piece. His goal was not an exact replica; rather, he aimed to create a moment, an idea, releasing the figure “hidden” inside the stone. As he wrote in a sonnet addressed to his friend Vittoria Colonna:

No block of marble but it does not hide

the concept living in the artists’ mind_

pursuing it inside that form, he’ll guide

his hand to shape what reason had defined.

Moses dominates the tomb, but it is flanked by two other figures, Leah and Rachel, which represent, respectively, the active and the contemplative life and introduce theological ideas hotly debated during the Reformation. Rachel represents faith, whereas her sister Leah embodies charity. In these two figures, Michelangelo refers to the debate raging over salvation through faith as opposed to salvation through works—a topic he often discussed with friends in his later years.

In depicting Moses, Leah, and Rachel on Julius II’s tomb, Michelangelo is comparing the pope to the man who released the Israelites from captivity and talked with God. The illustration would have been even more complete with the inclusion of the slave figures Michelangelo had been working on, but these figures were cast aside at some point in the decades of redesign.

In the end, only one face of the original four-faced design was installed, and it too was scaled back. Michelangelo’s assistants built the structure and sculpted the other figures, including the reclining figure of Julius II, Mary holding baby Jesus, the sibyl, the prophet, and four men in relief. The marble, quarried at different times and from different sources, does not all match. And Julius II’s remains were never removed from his “temporary” grave in St. Peter’s.

Julius II left the papacy stronger, wealthier, and larger. His personality and charisma allowed him great liberties and generated both respect and fear. Michelangelo found Julius II to be a kindred spirit, but theirs was a tumultuous relationship, one of battles and tantrums. The sculptor wrote of the pope, “One who knows how to handle him and who has given him trust, always will find him the best disposed person in the world.”

Rachel.

Julius II had wanted Michelangelo to build him a tomb that would impress history with its opulence and majesty. In the end, however, the pope’s tomb, for all the sculptor’s skill, is underwhelming. Yet, Julius can hardly be considered a minor figure in Michelangelo’s story. Not only was he one of Michelangelo’s greatest patrons, friends, and enemies, but he also set Michelangelo to work on what would become the artist’s most famous project: the Sistine Chapel.