Chapter 5

The Sistine Chapel

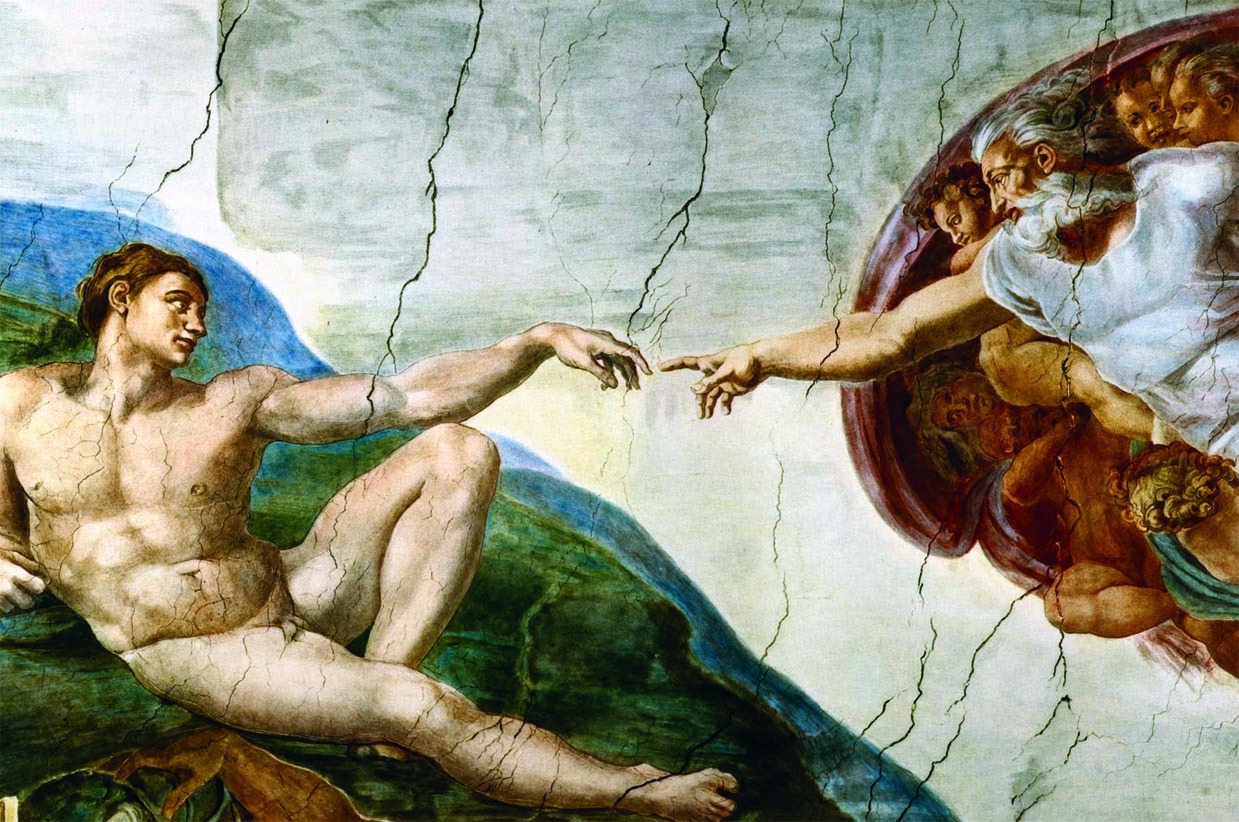

The Creation of Adam.

The Sistine Chapel was built in the late 1400s by Pope Sixtus IV as a replacement for the medieval Capella Magna, which was considered dark, damp, and gloomy. The chapel was built to host the Vatican’s papal conclave, during which the College of Cardinals elects the new pope in strict secrecy. Reusing the Capella’s foundation and materials, Baccio Pontelli and Giovannino de’ Dolci constructed a bastion of strength and security. It boasted slits for archers’ bows and secret openings from which boiling oil could be poured onto attackers. It also had windows near the ceiling, causing the Roman poet Brandolini to write, “Sixtus drove the darkness away and brought back the light of the sky, and to this place, that had been unaccustomed to it, he gave back the light of day.”

As befits its grand purpose, the chapel was decorated by the greatest masters of the day. Upon its completion in 1480, Lorenzo de’ Medici sent a group of Florentine artists to Rome to fresco the walls as a peace offering, marking the end of Florence’s war with the Vatican. The vaulted ceiling was frescoed by Piermatteo d’Amelia in a brilliant blue dotted with gold stars, representing the vast expanse of the heavens. The costly blue and gold colors made a dramatic impact.

After only a few decades, however, the chapel’s roof had begun to leak and structural repairs were needed. When Pope Julius II was elected, he was eager to fix the problems. He shored up the building and made it more sound. But the starry vault painted on the ceiling had sustained serious damage, and a crack patched with bricks and plaster ran through the sky. Julius II immediately considered enlisting Michelangelo to repaint the ceiling.

This drawing from Ernst Steinmann’s Die Sixtinische Kapelle depicts the Sistine Chapel before Michelangelo worked on it. Originally, the ceiling of

the chapel was frescoed in a deep (and expensive) blue with gold stars scattered across the sky. Italian frescoists often used ground stones to

achieve the deepest colors. The blue of the sky might have come from powdered lapis lazuli; the stars were real gold applied after the plaster dried.

One evening in the spring of 1506, a week or two after Michelangelo had fled to Florence, the pope and Bramante, the architect of the new St. Peter’s Basilica, were conversing over dinner. Also at the table was Piero Rosselli, a Florentine mason and friend of Michelangelo. Rosselli would later write to Michelangelo of the conversation.

White Smoke

Whenever a pope dies, the College of Cardinals meets in the Sistine Chapel to elect a new pope. The cardinals, the highest-level appointees within the church, are forbidden contact with the outside world during the conclave; the punishment for breaking the vow of secrecy that they take at the beginning of the meeting is excommunication.

Each cardinal receives a ballot for each round of voting, upon which he writes the name of his candidate. The ballots are then collected at the altar of the chapel in a chalice. They are tallied and burned after each vote. When there is no agreement, the ballots are mixed with straw to create black smoke; when a pope is elected, the smoke is white.

The pope informed Bramante that he would be sending the architect Giuliano da Sangallo to Florence to bring Michelangelo back to Rome. Bramante assured the pontiff that Michelangelo had no intention of taking on the project. He said Michelangelo had told him that he “did not wish to attend to anything but the tomb and not to painting.”

“Holy Father,” Bramante continued, “I do not think he has the courage to attempt the work, because he has small experience in painting figures, and these will be raised high above the line of vision, and in foreshortening. That is something different from painting on the ground.”

Bramante knew what he was talking about when it came to painting murals, but he was a poor judge of Michelangelo’s temperment and talent. It was true that Michelangelo had sold only one painting—the Doni Tondo, a circular picture (tondo means a round frame) of the Holy Family—since leaving Ghirlandaio’s workshop. But the Doni Tondo clearly attested to his skill. Bramante, or so Michelangelo suspected, had other motives for speaking ill of Michelangelo’s skills as a painter, namely to persuade the pope to give the commision to Bramante’s nephew, Raphael. Julius II was unswayed by Bramante’s protests, but put the idea aside for a year while he led his armies on the campaign to regain control of the Papal States.

Donato Bramante devoted himself to architecture in Rome and holds the distinction as the first architect of note in the Renaissance. His choices and tastes dictated architectural fashions for more than a century.

While Julius II waged war, Michelangelo was living simply yet comfortably in Florence. He bought a sizable farm outside of Florence that supplied him with wood, grain, olives, and grapes. He would continue to buy property throughout his life, and soon became the primary financial supporter of his entire family.

Michelangelo’s Florentine contentment was disturbed when Julius II returned to Rome emboldened by his conquests in the Papal States. He and Michelangelo had reconciled in Bologna in November 1506; in May 1508, the pope called the artist to Rome to take on the 1 Sistine Chapel ceiling. Reluctantly, Michelangelo agreed. The project would consume him over the next few years.

The Agony and the Ecstasy

The first task to be accomplished was the design and construction of the scaffolding that would enable the artist to reach the ceiling. Although Irving Stone’s novel The Agony and the Ecstasy presents a compelling image of Michelangelo lying on his back high above the chapel floor, the reality was probably much less dramatic.

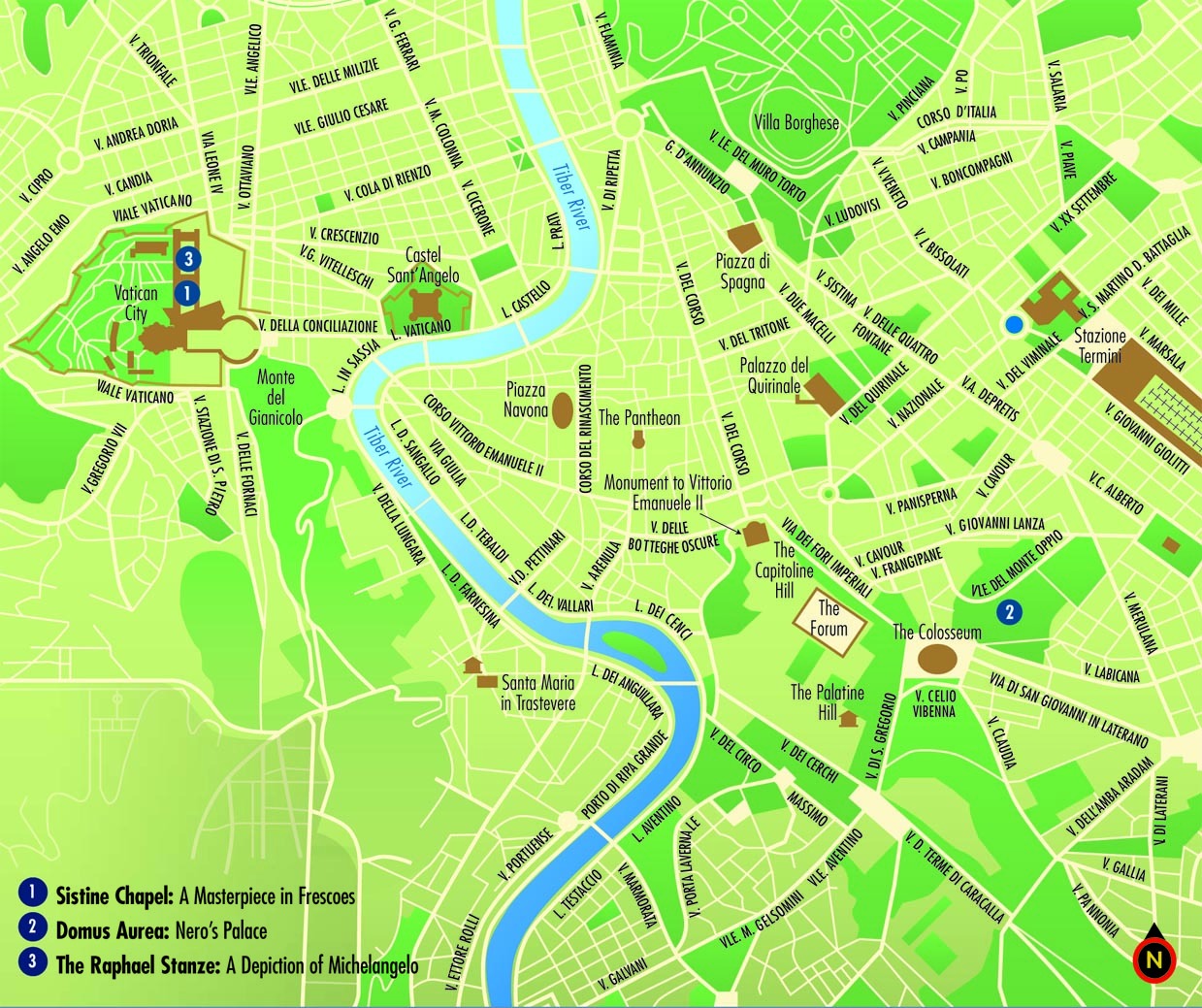

The Domus Aurea and the Sistine Chapel

In July 64A.D., an enormous fire raged through Rome for nine days, destroying much of the city. On the burnt land, the emperor Nero built one of the most opulent palatial complexes ever constructed, the 2 Domus Aurea, or Golden House. All its walls and ceilings were painted with fanciful scenes of animals, people, mythical beasts, and lush greenery. The long walls were embellished with faux architectural elements—moldings and doorways—that divided the enormous spaces into manageable sections and provided a structure to decorate. Fourteen hundred years later, this palace would inspire the Florentine frescoists commissioned to decorate the Sistine Chapel’s walls.

Over the centuries, the Domus Aurea was stripped of its gilding and jewels. Parts of it were filled in and became the foundation for other building projects. On other parts, gardens and vineyards began to grow, and cattle grazed over the site. In the mid-to late fifteenth century, the ceilings of the Domus Aurea weakened and holes opened in the hillsides. Unaware of what they had found, visitors began to frequent what they called “the grottoes,” lowering themselves in through the holes in the hills.

Standing at ceiling-level on top of piles of rubble, visitors rediscovered the frescoed grandeur of Nero’s palace, remarkably preserved for centuries. Artists, thrilled with the find, called the designs “grotesques” (because they thought they were in a grotto). When Lorenzo de’ Medici sent Florentine frescoists to work on the Sistine Chapel in 1480, they visited the grottoes. Pietro Perugino, Sandro Botticelli, Cosimo Roselli, Luca Signorelli, and Domenico Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s future teacher) drew inspiration from these works.

Like the painters of the Domus Aurea, the Florentine frescoists divided the long space of the Sistine Chapel’s walls with faux architecture, creating form and space from a flat wall. They employed fanciful and imaginative motifs from the Domus Aurea in their paintings, and set the stories they were telling among the ruins of Rome and in buildings resembling the rooms of the Domus Aurea.

The Domus Aurea stretched from the Palatine Hill to the Esquiline

Hill and included a lake and hunting grounds. When he moved into

his lavish palace, Nero is said to have exclaimed, “At last I can live

like a human being!”

Their scheme for the Sistine Chapel reflected the purpose of the room. Below Piermatteo d’Amelia’s blue sky was a tier of ancient popes, reminding the conclave of the historic and spiritual nature of their electoral task. Beneath the row of popes, in a band that extends all the way around the chapel, the painters depicted scenes from the lives of Moses and Jesus, the two most important figures in the Old and New Testaments. Each event from Moses’s life was paired with one from Jesus’s life, illustrating the parallels between their lives. The cycle continued around the chapel, with each panel facing the corresponding panel on the opposite wall. The scheme also drew connections between the Old and New Testaments, the old covenant symbolized by circumcision (The Circumcision of Zipporah) and the new by communion (The Last Supper).

Bramante suggested that the scaffolding be suspended from the ceiling. Rope and wood—both expensive commodities—were purchased to execute his design, but Michelangelo halted the work. How would the holes left by the suspended ropes be filled when the scaffolding was removed?

Michelangelo dismantled what had been built and designed his own scaffold. Because the materials were so expensive, he could work on only half of the chapel at once. But because his design was spare and efficient, the chapel could continue to be used while work went on. When the scaffolding was complete, the extra rope was sold and provided a dowry for Michelangelo’s carpenter’s two daughters. Later, Bramante applied Michelangelo’s technique when he needed scaffolding for St. Peter’s.

Building the scaffolding and preparing the ceiling to be frescoed took many months, during which Michelangelo worked out his design for the ceiling. He chose to depict the history of God and man working together, and produced a scheme consisting of several interrelated components. Down the center of the vault are scenes from Genesis, starting with Noah and working backward chronologically to Creation. Sitting on thrones set into the monumental trompe l’oeil architecture are the prophets and sibyls who predicted the coming of Christ. Above the windows in triangular frames are scenes of families: mothers, fathers, and children—the human family. Finally, the lunettes above the windows (where Michelangelo’s creations meet the popes) are filled with the ancestors of Jesus, establishing the lineage that runs from Moses to Christ. In each of the four corners of the room, spandrels tell stories of the victory of the Jewish people over peril. Between the primary figures, medallions, nudes, and dramatic architectural elements divide the space into regular geometric spans.

Once the design was worked out, Michelangelo prepared cartoons (full-size sketches) of the figures and architectural elements. He employed assistants, including Francesco Granacci and several other Florentine painters, to help prepare the plaster, transfer the cartoons, paint the smaller figures, and prepare his colors. Because the windows in the chapel are near the ceiling, the team had good lighting. The floor of the scaffolding hid the painting from viewers below and protected the floor of the chapel from falling debris, as well as preventing workers from falling to their deaths.

Italian Fresco Technique

Fresco painting relies on techniques that have remained the same since ancient times. Because water and moisture easily damage frescoes, the art form has thrived in dry climates. Preparation of the surface is labor intensive: The surface is dampened, and the workers lay on a layer of lime plaster called arriccio. Once the arriccio has dried, the artists start work. Pigments are mixed with limewater to form a bond with the wet plaster to which they are applied, creating a hard and durable surface. Painters work in small sections called giornata, or “a day’s work.”

Each giornata begins with a fresh layer of plaster called i ntonaco. While the plaster is still damp, the design is transferred to it, either from cartoons or freehand. The transfer can be accomplished in two ways: by using a stylus to trace the outlines into the damp plaster, or by using pinpricks to transfer finer details with a bit of charcoal dust.

Once the cartoons have been transferred, pigments—minerals ground to a very fine powder and mixed with limewater—are painted on using brushes. The brilliance of the colors and the textures created in the fresco can be manipulated by varying the amount of liquid mixed with the minerals. In some places in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo used almost no water, applying the pigment to the plaster with very little dilution, which created a brilliant finish.

Fresco a secco, dry fresco painting, can be used to touch up a painting once it is finished. The colors tend to flake off over time, however.

The Hall of Maps in the Vatican Museums offers a chance to take a close look at

frescoes from the late sixteenth century. As the dotted lines show, cartoons were

transferred using colored dust applied through perforations in paper to wet plaster.

Normally, the dots were then obscured with color; in this case, the plan changed but

the transfer marks remained.

Much of the organization and imagery of Michelangelo’s work recalls the Arch of Constantine and the Domus Aurea. The Arch of Constantine uses nude figures as decoration, much as Michelangelo uses small nude figures called putti as part of his design. The nudes, or ignudi, perform one of two functions: they hold up the ribbons “suspending” the medallions and they hold garlands of oak leaves and acorns, which are part of Julius II’s family crest.

Both the ignudi and the prophets illustrate Michelangelo’s adaptive qualities as an artist. The prophets he painted first—near the entrance wall—are classical and symmetrical. Moving across the ceiling, the figures become more and more athletic, taking on action at the end just as the ignudi do. Clothed and nude, floating without wings or halos, the figures illustrate his anatomical fascination.

Michelangelo applied the same techniques he used in sculpting to his painted figures. For example, he used crosshatching to create shadows, just as he did with a fine chisel on marble. For Michelangelo, his painting was most successful when he focused on the anatomy of his figures.

When the ceiling was cleaned during the late twentieth century, the giornate were mapped, revealing Michelangelo’s progress across the vaulted ceiling. The surface of the ceiling, it turns out, is not smooth. The plaster levels change from one giornata to the next.

As Michelangelo worked, he encountered problems. By the time he finished The Flood, for example, one of the nine scenes from Genesis, the work he had completed had begun to mildew. He saw this as an opportunity to walk away from the project and return to sculpting Julius II’s tomb. Julius II, however, sent Giuliano da Sangallo to advise Michelangelo. Sangallo “realized that Michelangelo had applied the plaster too wet, and consequently the dampness coming through produced that effect; and, when Michelangelo had been advised of this, he was forced to continue, and no excuse served.”

Michelangelo was also bothered by the fact that the chapel continued to be used while he worked. On June 10, 1508, the papal chamberlain recorded in his diary: “In the upper part of the chapel of the building work was being done with much dust, and the workmen did not stop as I ordered. For which the cardinals complained. Although several times I reproved the workmen, they did not stop; I went to the pope who was annoyed with me because I had not admonished them and the work continued without permission, even though the pope sent two successive chamberlains who ordered them to stop, which was done with difficulty.”

It wasn’t just chapel services that interrupted Michelangelo’s work. “While he was painting, Pope Julius often wanted to go and inspect the work; he would climb up by a ladder and Michelangelo would hold out a hand to help him up onto the scaffolding.” The spandrels in the four corners of the room illustrate scenes of salvation, but the head on Judith’s platter looks like that of Julius II.

The Sculptor in Rome

Michelangelo and his assistants worked for two years on the first half of the chapel, gaining speed and confidence as they proceeded. The painters completed The Creation of Eve in only four giornate, whereas The Flood, completed earlier, took twenty-nine giornate, not including a section that had to be redone because part of the fresco was destroyed and had to be reworked.

Upon descending from the scaffolding each day, Michelangelo headed home to his workshop and house at Piazza Rusticucci, where he read, worked on pieces destined for Julius II’s tomb, wrote poetry, and corresponded with his family—signing many of his letters “sculptor” despite the enormous painting project he was undertaking.

The Sibyls

Sibyls, or prophetesses, appear in Greek literature as far back as the fifth century B.C. Perhaps the most famous sibyl held court at Delphi, where her oracular visions became the stuff of legend. The Roman Empire imported the tradition, and sibyls could be found at Tivoli and Naples, among other places.

The sibyls Michelangelo depicts are those who predicted the coming of Jesus. Sibyls take on an important role in Renaissance art and are often depicted as women of strength and beauty. Michelangelo’s sibyls are not all beautiful, but they are all powerful.

The Libyan Sibyl.

Although now wealthy, Michelangelo lived a simple life, employing a modest staff of servants and cooks to maintain his household. He could have feasted sumptuously, but he enjoyed a diet much like that of the average Roman: pasta, tomatoes, bread, and wine. He probably began his day with a glass of wine and a piece of bread. Before midday he would stop to take the comestio, a light lunch consisting of bread with a little meat, perhaps some soup, and a salad. At the end of the day, for the prandium, he might have indulged in a little more meat, perhaps some macaroni, and certainly more bread and wine.

Romans in Michelangelo’s day frequented the small and generally inexpensive trattoria (neighborhood restaurant) for variety and convenience. With offerings such as pig’s liver, chicken, fritters, and stews, the smells emanating from local eateries drew people inside, where gentlemen mingled with laborers and conversation flowed with the wine.

Michelangelo’s personal routine was also simple. He worked late, went to church, and enjoyed his friends. His standards for hygiene were not very high, however—even for Renaissance Rome. “He constantly wore boots fashioned from dogs’ skins on his bare feet for months at a time, so that when he later wanted to remove them his skin would often peel off as well.”

His four brothers relied on him for financial support during much of their lives. One became a priest but was later defrocked. Two asked Michelangelo to set them up in the wool trade, which he did. His brothers also asked him to use his influence to secure positions for them in Rome.

Being away from his family was not easy for Michelangelo, but he likely savored the distance at times, for his family taxed his patience and temper. In June 1509, for instance, he chastised his brother Giovansimone: “To make it short, I can tell you for certain you haven’t a thing in the world, and your spending money and household necessities are what I give you and have given you for some time now, for the love of God and thinking you were my brother like the rest. Now I know for certain you are not my brother.”

For the most part, however, Michelangelo dispatched sweet words, not harsh ones, to his family. For instance, on September 15, 1509, while working on the first half of the ceiling, Michelangelo wrote his father:

On one occasion, Michelangelo requested permission to celebrate a feast day with his family in Florence, to which Julius II replied, “Well, what about this chapel? When will it be finished?”

“When I can, Holy Father,” replied Michelangelo.

Furious, the pope struck Michelangelo with a staff and roared, “‘When I can, when I can’t’; I’ll make you finish it myself.”

Michelangelo left in a huff and prepared, once again, to return to Florence. The pope’s chamberlain followed him home, bearing five hundred scudi and making excuses for the pope, “declaring that such acts were all signs of his favour and affection.”

Julius II continued to hound the painter, and Michelangelo complained that the pontiff’s impatience interfered with his progress. One day, when Julius II again asked when he would be done, Michelangelo replied, “When it satisfies me in its artistic details,” to which the pope replied, “We want you to satisfy us in our desire to see it done quickly.”

In September 1510, as work was nearing completion on the first half of the ceiling, Michelangelo’s brother Buonarroto became gravely ill. In a letter to his father, Michelangelo wrote that “if he were really bad, I would come up there by the post this next week, although it would damage me very much ... if Buonarroto is in danger, let me know, because I shall leave everything.”

Indeed, Michelangelo did “leave everything” and rush to Florence. His brother made a speedy recovery, but Michelangelo found that his father had withdrawn money from his accounts without permission. Explaining himself, his father wrote: “I said to myself, seeing your last letter, ‘Michelangelo won’t return for six or eight months from now and in that time I shall have returned from San Casciano.’ I will sell everything and will do everything to replace what I took.”

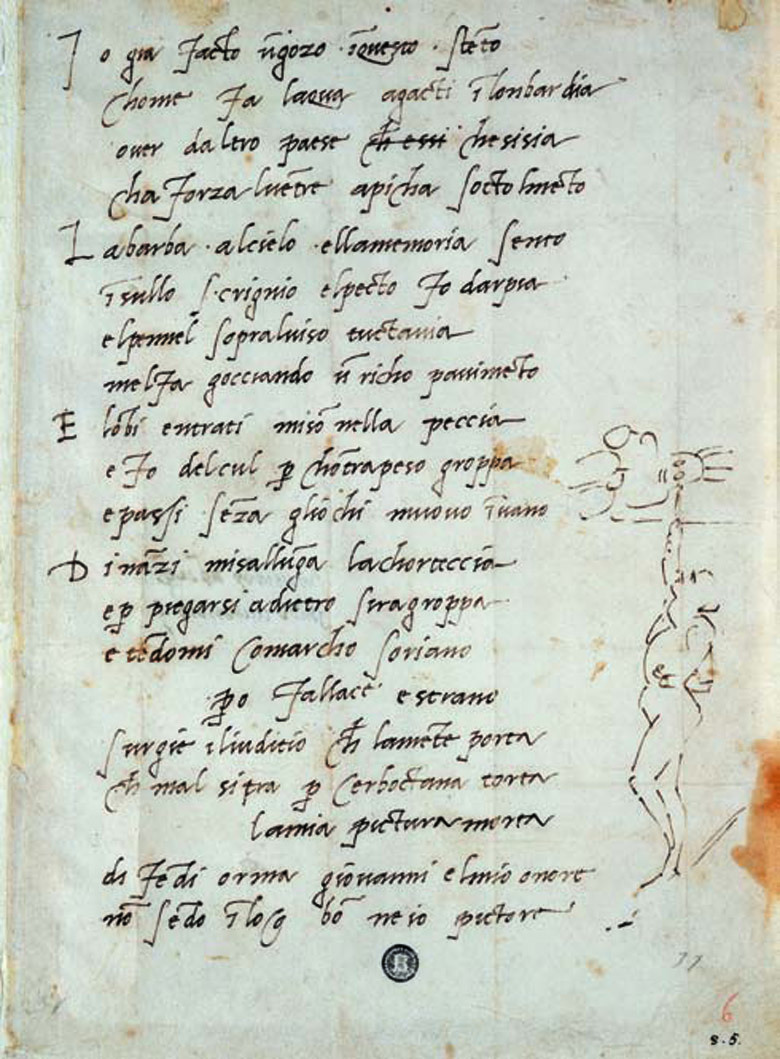

Sonnet to John of Pistoia on the Sistine Ceiling (1509–12)

In the corner of the page on which he penned a sonnet for a friend,

Michelangelo sketched himself on scaffolding, painting a figure above

his head.

The First Unveiling

While Michelangelo was in Florence, the pope had ventured to Bologna, where he fell ill and then proceeded to fight the French, who had advanced on the city. The first half of the ceiling was ready to be unveiled, but Julius II insisted that the scaffolding not be removed until he was in attendance. In the pope’s absence, work continued. Michelangelo shifted his attention to preparing drawings and cartoons for the second half of the ceiling. Although Michelangelo looked forward to the pope’s return because he wanted to be paid, the pope’s nine-month absence gave the artist and his team a much-needed respite. The work was taxing, and Michelangelo had developed severe eyestrain, which kept him from reading unless he tipped his head back.”

Raphael of Urbino (1483–1520)

Although Michelangelo seems to have been convinced that Bramante and Raphael conspired against him, it is unlikely the two colluded.

Raphael, the son of a painter as well as Bramante’s nephew and student, grew up in Urbino. When he arrived in Rome—too late in 1508 to vie for the Sistine Chapel commission—he was already well-known as a painter. He used Rome as a laboratory, immersing himself in the art surrounding him, including the surviving frescoes on the walls of the Domus Aurea. He also studied Michelangelo’s work whenever possible.

Raphael was soon commissioned by the pope to fresco three rooms in the Vatican used as an office and library. The 3 Raphael Stanze, as they are now known, were painted between 1508 and 1511. The most famous of the rooms, the Room of Segnatura, features figures of Theology, Philosophy, Justice, and Poetry hovering on the ceiling. Wall murals illustrate ideals important to humanists like Julius II: Parnassus (Poetry), The Cardinal and the Theological Virtues and the Law (Justice), The Disputation over the Most Holy Sacrament (Theology), and The School of Athens (Philosophy).

While Michelangelo was in Florence, Bramante, who had keys to the Sistine Chapel, snuck Raphael into the chapel and up onto the scaffolding to have a look at the work in progress. After seeing the first half of Michelangelo’s work in the Sistine Chapel, Raphael returned to The School of Athens. The fresco portrays the great thinkers of the ancient world debating and teaching. On the stairs, beneath the figures of Plato and Aristotle, Raphael chipped out the original image and applied fresh plaster, painting a morose, solitary figure slouching against a stone rail. The figure, known as the pensieroso (“the thinker”), wears leather boots and a cinched shirt—clothes more modern than those of any other figures—and his nose is flattened as if he had been punched long ago.

Three years after Michelangelo completed his work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Pope Leo X commissioned a series of tapestries from Raphael to run the circumference of the Sistine Chapel. For his labors, Raphael commanded a sum of 16,000 ducats—more than five times what Michelangelo had received for the chapel ceiling. The tapestries were stolen during the Sack of Rome in 1527 and were not restored until 1550. The Vatican Museums now display them under sensitive lighting to prevent fading or deterioration.

After seeing the Sistine Chapel, Raphael returned to his work The

School of Athens. He painted Michelangelo as Heraclitus, the

Greek philosopher, adding him to his pantheon of ancient scholars.

In June 1511, Julius II returned to Rome. Two months later, on August 15, 1511, the pope presided over morning mass in the Sistine Chapel. Pilgrims, dignitaries, and guests thronged the chapel, as eager as the pope to see the ceiling unveiled. According to Condivi, “The opinion and the expectation which everyone had of Michelangelo brought all of Rome to see this thing, and the pope also went there before the dust raised by the dismantling of the scaffold.”

The crowds were amazed by what they saw. The Rome Pietà had cemented Michelangelo’s place as a great sculptor; the Sistine Chapel ceiling established him as a tremendous painter.

Raphael may well have been among the crowd that morning. If so, he would not have been warmly embraced by Michelangelo, for Michelangelo suspected Raphael of asking Bramante if he, Raphael, could be allowed to finish the ceiling. “This greatly disturbed Michelangelo, and before Pope Julius he gravely protested the wrong which Bramante was doing him; and in Bramante’s presence he complained to the pope, unfolding to him all the persecutions he had received from Bramante.”

With the scaffold out of the way, Michelangelo could finally see the work from afar. Viewed from the floor, the figures in The Flood disappear into the crowded scenes and the ancestors of Christ bunch together, but the prophets are strikingly powerful. With this in mind, Michelangelo decided that the second half of the ceiling would feature fewer figures in each scene and that, like the prophets in the first half, those figures would be larger and the intensity of their actions more pronounced.

The first scene Michelangelo took on in the second half proved to be his most celebrated: The Creation of Adam. Accomplished in just two or three weeks, the scene features two suspended figures with very little scenery to anchor them.

Whereas the lunettes in the first half were painted in three or four days, the artists’ pace increased as they moved across the ceiling; the work labeled Roboam Abias was accomplished in a single giornata. Michelangelo was probably impatient to finish, especially because Julius II was not in good health. The death of the pope could mean financial headaches.

The images of God in the Sistine Chapel show Michelangelo’s transformation as he worked across the ceiling. In The Creation of Eve, God looks like a philosopher in Raphael’s The School of Athens. Dressed in robes and standing firmly on the ground, he assumes a human form. But the figure of God in The Creation of Adam soars through the air, loosely draped, with bare feet and powerful muscles. And the God who appears in The Separation of Light from Darkness takes on Zeus’s qualities, with a strong physique rippling under his loose garment.

The Desired End

In July 1512, Michelangelo complained to his brother Buonarroto: “I work harder than anyone who ever lived. I am not well, and worn out with this stupendous labour, and yet I am patient in order to achieve the desired end.” Julius II was not so patient and, despite battling ill health and the threat posed by French forces in the northern Papal States, he continued to harass the painter to finish.

Michelangelo painted

the scenes from

Genesis in reverse

chronological order.

As he gained

confidence and

observed his work

from the floor, he

created larger and

more dramatic

figures.

Finally, on October 31, 1512, the chapel’s doors were opened and Romans flocked to see the wonders therein. Michelangelo’s work created an immediate sensation in the city and beyond. In covering the enormous space with a program of panels and tremendous figures, Michelangelo had solved the problem of perspective that faces many muralists. The ceiling is impossible to see all at once, even though it soars sixty feet above the floor. No seat in the chapel has a better view than another—and all views are beautiful.

Julius II, pleased with Michelangelo’s work as well as with the hubbub it had created, showered the artist with gifts. However, Michelangelo never felt he was fairly compensated for his work, and he complained bitterly. For his part, Julius II, seeking to make his monument even grander, approached the artist about adding gold and ultramarine to the figures. He asked Michelangelo to reassemble the scaffolding and add sparkle because without it, he said, “It will look poor.” Michelangelo, reluctant to incur more expenses and to rebuild the scaffolding, replied, “Those who are depicted there, they were poor too.”

With Julius II’s death in 1513, Michelangelo could have been forgiven for thinking he would no longer be pestered by the pope about the Sistine Chapel. And, indeed, that was the case for no fewer than twenty-three years. But in 1536, he would be called back to the chapel again, this time to paint the altar wall for a very different kind of pope.