Chapter 6

Courting Controversy

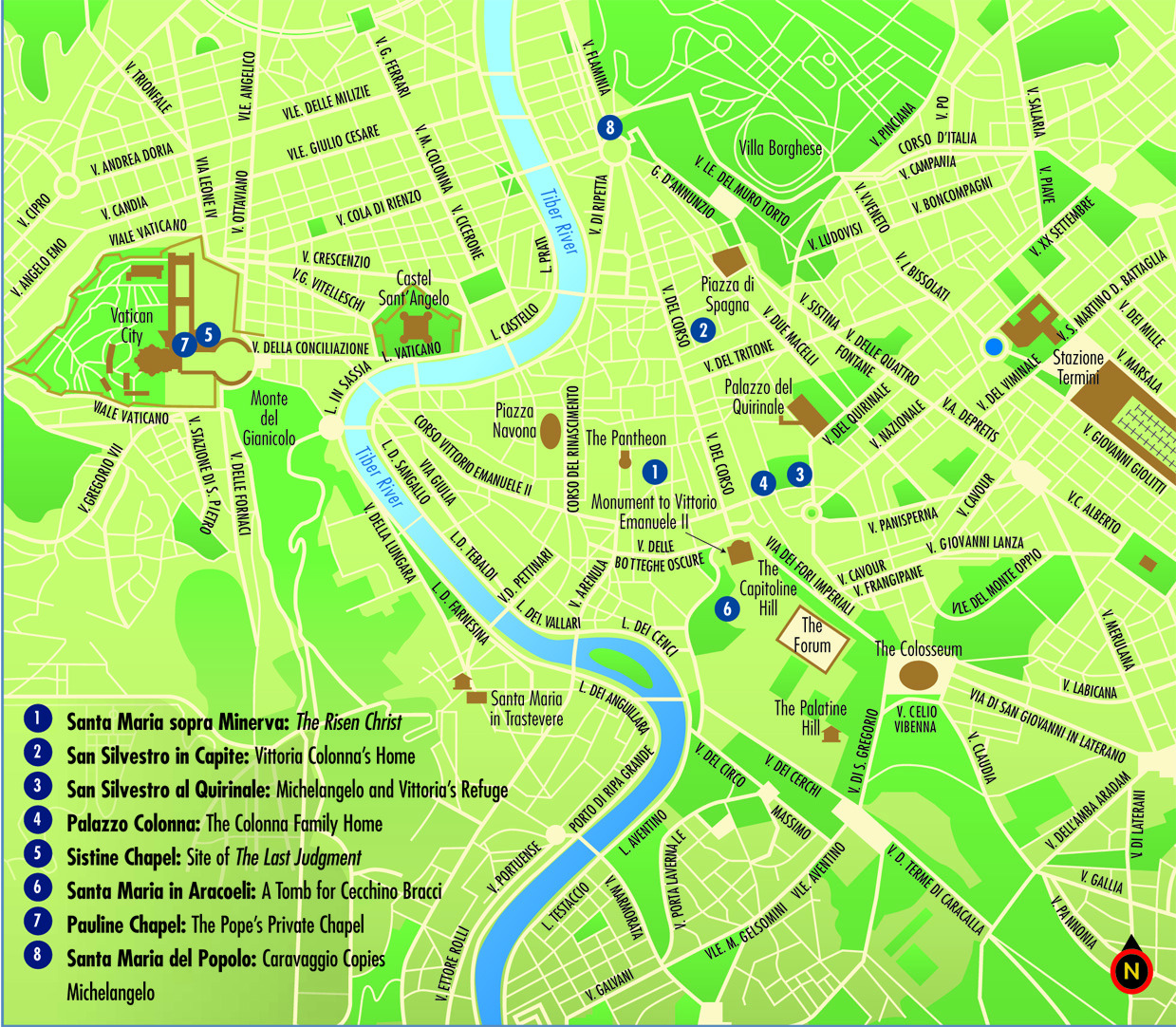

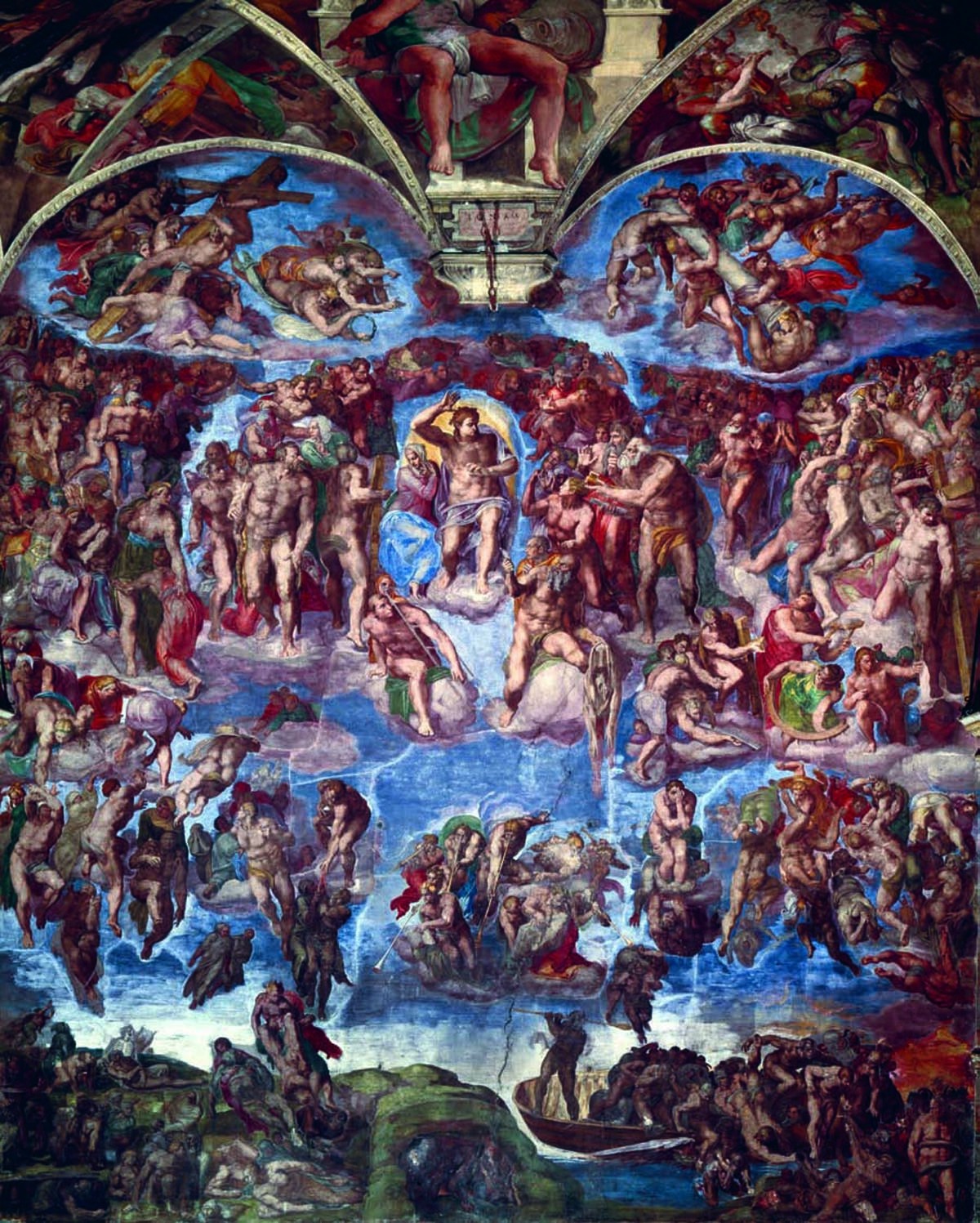

Michelanglo used the face of his friend Tommaso de’ Cavalieri for St. Sebastian (center right, holding arrows) in The Last Judgment

(1541).

Following the phenomenal success of the Sistine Chapel commission, Michelangelo found himself in great demand. The next commission he accepted, however, was a small one for a patron named Metello Vari: The Risen Christ, to be installed in the 1 church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Michelangelo signed the contract for the commission in June 1514 and began the work almost immediately. Unfortunately, he chose a flawed block of marble and had to abandon the first attempt.

After the death of Pope Julius II, the papal conclave chose a Medici pope, Leo X, who loved art and grandeur. Leo X set Michelangelo to work on the Chapel of Pope Leo X in Castel Sant’Angelo and the façade of the church of San Lorenzo in Florence. Both papal commissions interfered with Michelangelo’s progress on The Risen Christ, but in 1518, while juggling other projects, he selected a second block of marble and began the work again. The sculpture took three years to complete and was installed in March 1521.

The contract for the piece called for “a marble Christ, large as life, nude.” The concept of Jesus in the nude shows the powerful influence of ancient art: indeed, Christ looks like classical images of Apollo. Squeamish clergy later added a gilded loincloth to the figure, which remains today.

As with Moses and David, Michelangelo manipulated the figure’s proportions to his own purposes, but this manipulation has raised criticism because the intentions of the distortion are not immediately obvious. The figure appears to be disproportional from several angles, with a large torso and skinny legs; from behind, it looks misshapen. But when viewed from the left, the sculpture comes into focus. Jesus’s stance forces the cross to the forefront, and his body disappears behind it. Unfinished patches on the back of the sculpture indicate that Michelangelo did not intend for the viewer to see Christ’s back.

Michelangelo showed keen awareness of lighting and placement as a sculptor and as an architect. The natural lighting in Santa Maria sopra Minerva is dim and angled, coming from high windows. Critics argue that Michelangelo planned The Risen Christ using his understanding of light effects. Contemporary sketches show that The Risen Christ was originally placed in a niche in the wall to be seen from one viewpoint. The niche, representing the tomb, allows the sculpture to emerge from “the shadow of death” and directs the viewer to the most proportional view of the piece.

By depicting Jesus in Rome in The Risen Christ (1518–21), Michelangelo

emphasized the connection between the political and the

spiritual center of the church—reaffirming the mandate of the popes.

Michelangelo’s contemporaries adored the work. The painter Sebastiano del Piombo wrote that “the knees of that figure are worth all of Rome.” Indeed, the sculpture became an object venerated and adored by the faithful. Jesus’s foot, stroked and kissed for centuries, has at times been covered by a brass slipper to keep it from wearing away. Michelangelo’s patron Metello Vari was so pleased with the final product that he presented the artist with a horse. Yet, in the position it now occupies, The Risen Christ is easily overlooked among the other pieces in the sanctuary.

Santa Maria sopra Minerva, just a block from the Pantheon, sits on a site where a temple to Minerva

once stood. Sculptures, frescoes, oil paintings, and tombs (including those of Popes Leo X and Clement

VII) are crowded into small chapels lining the nave.

Back to Florence

Florentine Leo X wanted to leave his mark on his hometown, so he commissioned Michelangelo to return there. Commissions and then politics kept Michelangelo in Florence for nearly two decades. He completed The Risen Christ in Florence, sending it with his assistant, Pietro Urbino, to be installed in Rome. Many blame Urbino for “ruining” the work because he was charged with finishing the details and installing the sculpture.

While Michelangelo was living in Florence, Rome suffered a period of political turmoil and violence that left the city battered and bruised. Attempting to stifle the growing power of the Reformation, inspired by Martin Luther in Germany, Leo X aligned himself with Charles V, who was both king of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor. At that time, the Holy Roman Empire consisted of not just the Netherlands and much of Germany but also much of southern Italy, including Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia. Charles V was a bitter foe of the Reformation, which was finding allies among German princes eager to assert their independence from the Holy Roman Empire. He was also locked in a fight with France for domination of Europe, and he viewed Italy as the key to winning that struggle. But the French had allies in much of northern Italy, and in 1524, Pope Clement VII switched sides and joined the French, hoping to check Charles V’s grab for power.

In response, Charles V sent an army to Rome. When his troops arrived on May 6, 1527, they had not been paid in months; their leader, the Constable of Bourbon, was killed at the city gates. Desperate, furious, and leaderless, the troops abandoned the rules of warfare and ravaged the city. The streets were filled with the bodies of civilians as soldiers advanced through the city, neighborhood by neighborhood. By nightfall, Spanish troops had taken Piazza Navona and Germans held Campo dei Fiori.

The invading troops, many of whom were Lutheran, searched for cardinals and religious booty; they also committed terrible atrocities. Women and children were raped. Food stores and homes were burned. Rotting bodies littered the streets while terrified families barricaded themselves in their homes for weeks. Others fled to the countryside. To the troops, works of art represented the arrogance and excess of the papacy; as they rampaged through the city, they destroyed an untold number of priceless pieces. The stained glass from France that Bramante had designed for the new St. Peter’s Basilica was among the casualties.

Many of Rome’s artists joined the exodus from the city. Some, however, were not so lucky as to escape. In the midst of the siege, Francesco Mazzola, known as Parmigianino, was at work painting an image of Saint Jerome. German troops stormed in, threatening to kill him. The artist persuaded them to take his pens and drawings as a ransom for his life. Vincenzo da San Gimignano, another painter, became violently depressed. Visions of the horrors he witnessed rendered him unable to work, and he eventually took his own life.

Fortunately for Michelangelo, he had secured a plum commission in Florence: the Laurentian Library at San Lorenzo. He was at work on this commission when Charles V sacked Rome. For the next seven years he would work steadily on civic projects in Florence. His grandest commissions came at the hands of the papacy and the Medici family, and Michelangelo often found himself perched precariously as the papacy changed hands between families. When the Medici were in control, Michelangelo had more work than he could manage. But when their fortunes and funds ran low, he had to position himself carefully to secure other commissions. Because Michelangelo was a republican, Florence became an unfriendly place for him in the mid-1530s. After Alessandro de’ Medici assumed the role of tyrant and expelled the last of the old republican government, Michelangelo joined the ranks of Florentine expatriates. In 1534, he left Florence, never to return.

Charles V’s army plunders Rome in 1527.

A Cadre of Friends

Michelangelo has sometimes been painted as a stingy, friendless genius, too busy with work to maintain relationships. In 1509, while painting the Sistine Chapel, he wrote to his brother Buonarroto, “I live here in great toil and great weariness of body, and have no friends of any kind and don’t want any, and haven’t the time to eat what I need.

Michelangelo focused most of his energies on his art. A friend once remarked, “It’s a pity you haven’t taken a wife, for you would have had many children and bequeathed to them many honorable works.” Michelangelo replied, “I have too much of a wife in this art that has always afflicted me, and the works I shall leave behind will be my children, and even if they are nothing, they will live for a long while.”

In addition, over the years, Michelangelo developed a reputation for having a temper—his terribilità. Some acquaintances considered him arrogant; others found him eccentric, even bizarre. Yet he was fiercely loyal to those who won his respect. His relationships crossed socioeconomic, gender, and age boundaries to include members of the nobility and the privileged clergy, writers and fellow artists, men and women, and those older and those younger than himself. Many of Michelangelo’s friendships spanned decades.

His relationships with his employees were also longlasting. Michelangelo kept careful records of their names, wages, and the projects on which they worked. Many stayed with him for years. He paid them well, provided them with housing, and was involved in all aspects of their lives. His generosity helped ensure their loyalty and afforded him a stable workforce, committed to the quality he valued and familiar with his working style. He provided the basic tools they needed: benches, rulers, stools, and a smith to sharpen their tools. They, in turn, carried out his work and upheld his exacting standards. Many of his employees earned nicknames revealing their personalities or physiques and their employer’s affections for them: the She-Cat, Knobby, Fats, the Anti-Christ, and Little Liar.

When Michelangelo met the young artist Tommaso de’ Cavalieri (c. 1518–87), a handsome Roman gentleman with good breeding and a good education, he found a kindred spirit. Although Michelangelo was fifty-seven years old when they met, he presented the younger man with poetry and drawings. He wrote a letter from Florence, touchingly awed that Cavalieri had responded to his tokens: “If it is really true that you feel within as you write me outwardly, as to your judging my works, if it should happen that one of them as I wish should please you, I shall much sooner call it lucky than good.”

Sonnet to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri (1533)

Cavalieri, a charming man, assumed the role of younger companion. He wrote, “I promise you, indeed, that from me you will receive an equal, and maybe a greater exchange, who never cared for any man more than for you, nor ever wanted any friendship more than yours; and if in nothing else, at least in this I have very good judgment.” The relationship between the two men sparked new bursts of creativity in both as they exchanged letters, poems, and drawings.

Much has been made of Michelangelo’s relationship with Cavalieri; some biographers have cast them as lovers. Perhaps they were. His verses written for Cavalieri do not differ much from those written for other friends—men and women—but they show an intense devotion and love. Given Michelangelo’s spirituality and his increasing devotion to a pious life, he may have spent his energies in chaste adoration—whatever his sexual preferences were. Michelangelo’s poetry for Cavalieri hints at desire but also reflects the ideas of Platonic love, which he embraced as he aged.

Cavalieri remained friends with Michelangelo until Michelangelo died, and Michelangelo left some of his projects in Cavalieri’s hands, including the completion of his redesign of the Campidoglio.

Vittoria Colonna: A Friend in Faith

In 1536, Michelangelo met another kindred spirit: Vittoria Colonna, the Marchese of Pescara, who had married at nineteen and was widowed by thirty-five. She mourned the death of her husband intensely and wrote scores of poems expressing her sorrow. Rather than marrying again, as her brothers wished, Colonna devoted her life to works of charity and intellectual pursuits, which brought her to Rome, where she made Michelangelo’s acquaintance.

When Vittoria Colonna died in 1547, Michelangelo grieved deeply.

Condivi wrote, “She often traveled to Rome from Viterbo and other

places where she had gone for recreation and to spend the summer,

prompted by no other reason than to see Michelangelo; and he in

return bore her so much love that I remember hearing him say that his

only regret was that, when he went to see her as she was departing

from this life, he did not kiss her forehead or her face as he kissed her

hand. On account of her death he remained a long time in despair and

as if out of his mind.”

Colonna made her home in Rome at 2 San Silvestro in Capite, occupying a room in the adjoining convent. She had the ear of Rome’s most powerful men, and she was not afraid to wield her influence. Her relationship with Michelangelo flowered, and soon Michelangelo, Colonna, and Cavalieri were enjoying each other’s company regularly.

Michelangelo and Colonna exchanged poems and met on Sundays at 3 San Silvestro al Qui r inale, just down the road from the Piazza del Quirinale, for afternoon talks on the terrace. Their conversations often revolved around theological and philosophical questions; both the artist and the widow struggled with questions raised by the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation.

San Silvestro in Capite, on Piazza San Silvestro.

A Personal Theology

Michelangelo’s devotion to the nude and the human body drew criticism and allegations of immorality. Like Plato, Michelangelo saw the contemplation of the human body and human beauty as a means to contemplation of divine beauty—the ultimate form hidden by flesh. Condivi wrote,

Spirituality was as much a part of Michelangelo’s creative life as it was part of his intellectual and social life. He felt that his creative process was a result of what Plato called furor divinus, or divine madness—Michelangelo called it a “seizure of the soul”—in which God takes hold of the body and allows the soul to experience divinity.

An artist, Michelangelo wrote, “must maintain a good life, and if possible be holy, so that his intellect can be inspired by the Holy Spirit.” When a friend asserted that God wanted Michelangelo to be an artist, he replied that he was nothing but “a poor man and of little value, a man who goes along laboring in that art which God has given me for as long as I possibly can.”

Michelangelo believed that God revealed himself in glimpses and that the intention of all work should be the glorification of God through the use of one’s talents in an effort to attain greater communion with God.

Madrigal to Vittoria Colonna

A man, a god rather, inside a woman,

Through her mouth has his speech,

And this has made me such

I’ll never again be mine after I listen.

Ever since she has stolen

Me from myself, I’m sure,

Outside myself I’ll give myself my pity.

Her beautiful features summon

Upward from false desire,

So that I see death in all other beauty.

You who bring souls, O Lady,

Through fire and water to felicity,

See to it I do not return to me.

This Christian application of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and other theories gained popularity during the Renaissance, and Michelangelo’s circle of friends would often debate these ideas.

Michelangelo designed the tabernacle behind the altar at San

Silvestro in Capite; it holds the relics of St. John the Baptist as well

as the vera-imago, a cloth with the image of Christ’s face. Vittoria

Colonna arranged for Michelangelo to view the cloth while he was

painting The Last Judgment.

Michelangelo studied the Old and New Testaments and developed a deep familiarity with the Scriptures. He also read the works of great theologians. Images and stories from antiquity infused his perspective on religion; the Virgin and the sibyl, the putto and the infant Jesus, Christ and Apollo took interchangeable forms. A devout Catholic, Michelangelo believed in the power of personal prayer and asked that others pray for him. He and Colonna both also believed in the power of good works and charity—ideas that in their day smacked of Lutheranism.

The Reformation

In December 1510 two Germans from an Augustinian monastery entered Rome. One was a twenty-seven-year-old monk from Erfurt named Martin Luther. When Luther arrived at Porta del Popolo, he prostrated himself, declaring, “Blessed be Thou, holy Rome!

Much of Luther’s time in Rome is the subject of legend. Did he hear the voice of God as he climbed the steps of the Scala Santa in the Lateran Palace? Perhaps. But the seeds of what would become the Reformation were definitely sown on that trip. Luther was appalled by the casual—and sometimes irreverent—attitudes Rome’s clerics displayed, and later accused priests of celebrating mass in a “slapdash fashion.” While the casual bearing of the clergy offended him, the fact that some were homosexual and many had syphilis infuriated him. He was also angered by Rome’s rampant poverty, prostitution, and pollution. He was taken ill while there, and blamed his sickness on the dirty air of the filthy city.

While in Rome, Martin Luther observed the construction of the new St. Peter’s Basilica. Seven years later he would post his “Ninety-Five Theses”—objections, in part, to the fundraising tactics employed by the Vatican to pay for the enormous building project—and launch what we now know as the Reformation. Begun as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church, the Reformation would end with the division of Western Christianity into the Catholic and Protestant churches.

As a priest, Luther longed for a less political and more transparent institution. He wrote prolifically about his ideas for change; thanks to the printing press, his words traveled quickly throughout Europe. But he was viewed in Rome not as a reformer but as a heretic. He was tried and eventually excommunicated for railing against the church. Yet, some German princes liked Luther’s teachings. Eager to be out from under the pope’s thumb, they became Protestant principalities, offering Luther safe haven and providing a fertile ground in which the Reformation could develop and grow.

Martin Luther.

As a testament to their intellectual pairing, the artist celebrated Colonna in many poems as a woman with whom he could match wits and explore ideas.

Michelangelo made several drawings for his friend, including a pietà and a crucifixion. Of the crucifixion, Colonna requested the addition of a few angels à la Raphael, to which Michelangelo objected, but he sketched them in anyway. The note accompanying the drawing of the crucifixion vowed, “I have wished to do more for you than for any man I ever knew in the world; but the great business in which I have been and am has not allowed me to let your ladyship know this.” He designed a tabernacle at the Basilica di San Silvestro in Capite—her residence—perhaps in her honor or at her request.

Galleria Colonna

Vittoria Colonna’s extended family owned seven palazzi in Rome in the sixteenth century. The most famous sits at the intersection of Via Quattro Novembre and Via della Pilotta: the 4 Palazzo Colonna.

Little mention was made of Colonna in the family home; she never actually lived there. But in a corner of the Sala della Colonna Bellica (Room of the Battle Column) is a portrait of a beautiful woman in a green gown. The painting, by Bartolomeo Cancellieri, is thought to be of Colonna.

The room may look familiar to film buffs, for this is where Audrey Hepburn held court in the final scenes of Roman Holiday as she expressed her love for Rome and for her host, played by Gregory Peck.

The Last Judgment

Pope Paul III had long admired Michelangelo’s talent, so when he was elected to the papacy in 1534, the pope immediately called the artist to the Vatican. He wanted Michelangelo to return to the 5 Sistine Chapel, this time to paint The Last Judgment on the wall above the altar. Michelangelo tried to decline, citing his continued involvement with Julius II’s tomb, but the pope would not hear it. “I have had this desire for thirty years, and now that I am Pope, am I not to satisfy it? I will tear up this contract, and, in any case, I intend to have you serve me!”

While awaiting Michelangelo’s arrival in Rome, Michelangelo’s friend Sebastiano del Piombo prepared the wall for the project, but he prepped it for an oil painting, not a fresco, and did not consult with Michelangelo. When Michelangelo found out, he flew into a rage, declaring that only women and lazy people painted in oils. He installed a new wall at an angle that allowed for ventilation, preventing an accumulation of dust on the fresco. In May 1536, Michelangelo began work—twenty-three years after completing his first venture in the same room.

The addition of The Last Judgment changed the focus of the Sistine Chapel significantly, directing attention to the altar wall. To install his commission, Michelangelo had to destroy two frescoes in the Moses and Jesus cycles: The Finding of Moses and The Adoration of the Shepherds, both by Perugino. In addition, two of Michelangelo’s own lunettes were destroyed, along with images of several popes and the altarpiece, also designed by Perugino.

Unlike the other frescoes in the chapel, The Last Judgment lacks a frame and a fixed viewpoint. The wall looks as if the chapel is open to the sky, essentially creating an enormous “window” through which the scene is seen. Michelangelo’s Christ, an Apollo-like figure set off in a golden haze, moves actively, saving souls. He looks downward, wounded hand raised as if ready to swoop up a person to bring to his side. Mary, already saved, looks about her at the company of saved souls.

Michelangelo studied the works of Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), a Florentine poet. Dante’s influence is especially powerful in Michelangelo’s vision of Hell. Like Dante, Michelangelo blends the stories of Greek mythology, including characters such as Charon and Minos, with Christian concepts of salvation and damnation.

In most paintings of the last judgment by Renaissance artists, characters headed to Heaven wear expressions of pleasure and piety—as if they deserve to be saved. The figures of the saved in Michelangelo’s version are strikingly different. Michelangelo presents the miracle of salvation according to Catholicism: no one deserves to be saved because all are sinners, yet the faithful are saved. Some of the saved wear expressions of fear and confusion, and the faces of the damned bear the surprise and sorrow of their fate. But Michelangelo’s most important theological statement appears at the top of the composition: figures bearing the symbols of the Passion (the cross, the crown of thorns). The moment depicted reminds the viewer not just of the promise of being saved but of the means (Christ’s crucifixion) by which Catholics believe that salvation is possible. Michelangelo’s composition becomes not a warning against sin and damnation but a treatise on grace and salvation.

Michelangelo filled his depiction with nudes, something that would bring criticism for the remainder of his life. Time and again, Michelangelo maintained that physical beauty reflects spiritual and moral beauty. Yet he also distinguished between artificial and physical beauty. No clothes—no matter how grand—could disguise a sinful soul.

Known to be a shabby dresser, Michelangelo put little stock in outward frills. For example, a priest Michelangelo knew arrived one day “dressed in buckles and silk.” Michelangelo wryly commented, “Oh, you do look fine! If you were as fine on the inside as I see you are on the outside, it would be good for your soul.” He filled his Heaven with gorgeous, muscular bodies, largely unfettered by the human constraints of clothing; meanwhile, the bodies of the damned writhe and wrinkle in ugly decay. Their bodies, not their clothes, reflect the condition of their souls.

When he erected the scaffolding in the Sistine Chapel for the first time, Michelangelo had been a young man. But much had changed since 1508. As he worked on The Last Judgment, he was keenly aware of his own aging body and the toll his work had taken on it. At sixty-five, when he had almost completed the fresco, Michelangelo fell from the scaffolding and hurt his leg. He hid away in his home in intense pain. After a few days a physician friend, Baccio Rontini, broke in and found him “in desperate shape.” Rontini cared for his friend until he healed and could return to work.

Michelangelo rewarded some of his loyal friends and enemies with immortality. The Last Judgment is filled with likenesses of those familiar to him, some flattering and some less so. St. Sebastian, a beautiful heroic figure holding a brace of arrows, may be Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. Urbino, Michelangelo’s faithful assistant, appears as St. James. St. Peter, according to some, bears the features of Pope Paul III, an appropriate homage.

The Restoration of the Sistine Chapel

The frescoes of the Sistine Chapel received a thorough cleaning and restoration between 1979 and 1999. The cleaning process removed centuries of smoke residue and varnish, which had obscured and darkened Michelangelo’s work. Although some art historians argued that the darker patina was historically correct, the cleaning process revealed the same brilliant and bold use of color that Michelangelo’s contemporaries had applauded.

In Greek mythology, Minos is the judge of the underworld. In The Last Judgment, he has

the face of Cesena, who disagreed with Michelangelo’s portrayals of nudes.

Two portraits in particular stand out. One is of Biagio da Cesena, the chamberlain of the Sistine Chapel. Cesena came with Paul III to see the painting in progress. When the pope asked what he thought of the work, Cesena said that he disapproved of nudes in holy places. In response to this remark, Michelangelo painted Cesena’s face with donkey ears to represent Minos in Hell. Positioned prominently above a doorway, a snake wraps around Minos’s body and swallows his penis. When Cesena complained to the pope about the depiction, Paul III reportedly replied that he could have helped, had Michelangelo put him in Purgatory, but he could do nothing for those in Hell.

The other striking portrait is of Pietro Aretino, whose features are given to St. Bartholomew. Aretino was an art critic, and the portrait may have intended to assuage Aretino’s anger with Michelangelo. Aretino had written Michelangelo in 1537 requesting drawings and making suggestions for The Last Judgment. Michelangelo paid little attention to Aretino, which infuriated the critic, for Aretino wanted to be made a cardinal and he hoped to use a close association with the artist to win the respect of the other cardinals.

When the painting was unveiled, Aretino—like many other Romans—was scandalized that Michelangelo had filled an altar wall with nudes. “Is it possible,” he asked Michelangelo in a letter of November 1545, “that you, who as a divine being do not condescend to the society of men, should have done such a thing in the foremost temple of God? Above the main altar of Jesus?” He continued, “I, in lascivious and immodest subject matter, not only use restrained and polite words, but tell my story in pure and blameless language. But you, in a subject matter of such exalted history, show angels and saints, the former without any of the decency proper to this world, and the latter lacking any of the loveliness of Heaven.” The Last Judgment “would be appropriate in a voluptuous whorehouse, not in a supreme choir.” Aretino concluded with veiled threats of exposing “Tomai”—perhaps an effort at blackmailing Michelangelo, for he still wanted drawings from him.

Even after penning such a strident letter, Aretino had the gall to write again, requesting Michelangelo to let him have “some of the drawings with which you are prodigal to the flames but so miserly to me.

Reactions

According to Giorgio Vasari, Julius II had intended for the artist to paint The Last Judgment—complete with nudes—over the altar of the Sistine Chapel and the Fall of the Rebel Angels on the back wall. In the days of Julius II, the classical nude exemplified perfection in art. But attitudes about art had changed since Julius’s death. The Reformation—and the equally fierce Counter-Reformation, with which the papacy and its allies fought back against Protestantism—unleashed a tide of puritanism. No longer was the classical and antique revered; nudity, once considered beautiful, was now deemed indecent.

St. Bartholomew, who was skinned alive, is usually portrayed carrying his

own skin. In The Last Judgment, the face on the skin is that of Michelangelo.

Michelangelo anticipated that his art might suffer in such a censorious climate:

The fact that Michelangelo did not make a physical distinction between the saved and the fallen also opened him up for criticism. Halos and wings had become the fashion of the day—such signs of salvation helped to emphasize the hierarchy some clung to as the salvation of a troubled church.

Luigi del Riccio

One of Michelangelo’s closest friends, Luigi del Riccio, cared for him in 1544 and 1545 when Michelangelo fell ill. Michelangelo wrote to a nephew, “I have not found a better man than him to do my business, or more faithful.”

Del Riccio had adopted a young relative named Cecchino Bracci, who, in 1544, died at the age of sixteen. Michelangelo soothed his grieving friend with poems and further honored his friend’s grief by designing a tomb for Bracci, installed in 6 Santa Maria in Aracoeli, a church just off the Piazza del Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill. One of Rome’s most ancient basilicas, Santa Maria in Aracoeli sparkles with the light of many crystal chandeliers, invoking the vision of the heavens for which it is named.

Michelangelo wrote forty-eight epitaphs, a sonnet, and a madrigal about the death of young Cecchino Bracci, as well as designing this tomb for the teenager. His assistant Urbino made and installed it.

On October 31, 1541, Paul III unveiled The Last Judgment—twenty-nine years to the day from the first revelation of Michelangelo’s work in the chapel. Whereas people had marveled at Michelangelo’s work on the ceiling (the nude figure of Adam had been acclaimed as a triumph), The Last Judgment garnered mixed reviews primarily because most of the figures in it were nude.

Michelangelo was not the only one who remembered and revered the power of the nude, and his fresco provided a powerful example for those who strove for anatomical accuracy. Thanks to printing presses, copies of The Last Judgment were available far and wide in a relatively short time. Soon the work was held up as a “school for artists”—a textbook of sorts, offering artists a wide range of figures to study and to copy. When Michelangelo saw painters copying his work, he mourned, “Oh, how many men this work of mine wishes to destroy!”

Although artists sought to imitate the work, most critics tried to excoriate it. Michelangelo was even attacked by those he considered his friends. Many within Vittoria Colonna’s circle of intellectuals and theologians accused Michelangelo of heresy.

Paul III did not forcefully defend Michelangelo, but he did not condemn the painting either. His successors, however, were more vocal. Paul IV (1555–59) even considered destroying the Sistine Chapel and other “immodest” works of art as a means to improve public morals.

Calls to censor or destroy the Sistine Chapel’s nudes would plague Michelangelo for the remainder of his life. He remained steadfast in defense of his work, however. When asked to amend the fresco, he replied defiantly, “Tell the pope that this is a small matter and can easily be amended; let him amend the world and pictures will soon amend themselves.”

With the election of Pius IV (1559–65), the calls for censorship found a sympathetic pontifical ear. In 1563, twenty-two years after The Last Judgment was unveiled, the Council of Trent took up a discussion of art, specifically Michelangelo’s frescoes. On January 21, 1564, the council ordered that the frescoes be changed.

But Michelangelo had loyal friends in the Curia (the Vatican’s political administration). The eighty-nine-year-old artist was dying, so they chose Michelangelo’s student, Daniele da Volterra, to make the changes, and allowed him to wait until after the artist’s death.

First Volterra made alterations—painting drapery over key figures and clothes on others. Then, rather than clothing St. Catherine and St. Blaise, Volterra destroyed them and painted new, clothed figures. He sought to preserve the intention and spirit of his master’s work while pleasing the squeamish clergy. For his pains, Volterra was known forever after as “the breeches maker.” Volterra was not the last painter to alter The Last Judgment. Several popes over the centuries appointed painters to make changes, though over time the fresco suffered more from smoke damage and neglect.

The Private Chapel

Despite the controversy over The Last Judgment, Michelangelo continued to receive papal commissions. Paul III wanted a new private chapel. The 7 Pauline Chapel is buried within the Vatican complex and is hardly known to the public—or even to scholars. For the pope, however, it is a private place of worship and is used regularly. The art Michelangelo created for Paul III’s commission turned out to be his last frescoes: The Crucifixion of Saint Peter and The Conversion of Saul.

In scale, the project cannot compare to The Last Judgment or the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo began work in November 1542. His progress was delayed by illness in the summer of 1544, but he completed the Conversion in 1545—the same year he finished installing the tomb of Julius II. His progress in the Pauline Chapel was further slowed by his appointment as architect for both St. Peter’s Basilica and the Palazzo Farnese, but he finally finished the frescoes in 1550, at the age of seventy-five.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1546–50).

In 1549, as he worked in the Pauline Chapel, Michelangelo wrote, “Painting is to be considered the better the more it approaches relief, and relief is to be considered the worse the more it approaches painting; and therefore I used to feel that sculpture was the lantern of painting and that there was the difference between them that there is between the sun and moon.” His frescoes attempt to bring painting closer to sculpture. They focus on dramatic events with little in the background to ground the figures. Like the Rome Pietà, the frescoes tell the story of moments.

In The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1546–50) Michelangelo chooses the moment of agony as the cross is being raised and Peter lays suspended across the space in twisted pain, his face contorted and pleading. In The Conversion of Saul, the Holy Spirit suddenly grips Saul, traveling along a road, and his name and his path in life change forever. The Conversion also emphasizes the emotion of a moment—the moment when Saul converts. He is struck by fear and is overpowered by God.

At the height of the Reformation, Michelangelo chose subjects that affirmed the legitimacy of the papacy and its ties to Rome: Peter and Paul, the spiritual guardians of Rome, both of whom were martyred in the Eternal City.

Perhaps because Michelangelo presented such bare compositions, the Pauline Chapel frescoes stirred neither controversy nor adulation. After Michelangelo’s death, drapes were added to some of the nudes, but the frescoes were largely ignored as the work of an elderly, doddering artist. Because of its location deep in the private areas of the papal complex, the Pauline Chapel is rarely open to the public. In 2004, the Vatican announced that Michelangelo’s frescoes were being cleaned and restored using the same techniques that proved successful in the Sistine Chapel.

Caravaggio’s Crucifixion and Conversion

Relatively little is known about Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610). Working in Rome, Caravaggio created dramatic and intimate scenes, drawing on the pieces that surrounded him. In the 8 church of Santa Maria del Popolo (off the Piazza del Popolo, north of the Spanish Steps), Caravaggio created the same pairing of subjects that Michelangelo did for the Pauline Chapel. Unlike the Pauline Chapel, Santa Maria del Popolo is relatively easy to visit.

Caravaggio’s Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1600–01) draws deeply from Michelangelo’s work—the two Peters take the same position and have strikingly similar features. The compositions are similar, but Caravaggio takes a much darker view of the scene. His Conversion on the Way to Damascus (1601), however, differs markedly from Michelangelo’s. Saul (who later became St. Paul), a Pharisee, was traveling on the road when he was suddenly converted to Christianity. Where Michelangelo illustrates a crowded scene with Christ in the sky performing the conversion, Caravaggio depicts Saul struck from his horse and bathed in light. In both Crucifixion and Conversion, Caravaggio makes significant use of chiaroscuro (using light and dark to achieve depth in painting). Although Michelangelo and other Renaissance artists understood chiaroscuro, painters of the seventeeth and eighteenth centuries, such as Caravaggio and Rembrandt, perfected and exploited the technique.