Chapter 7

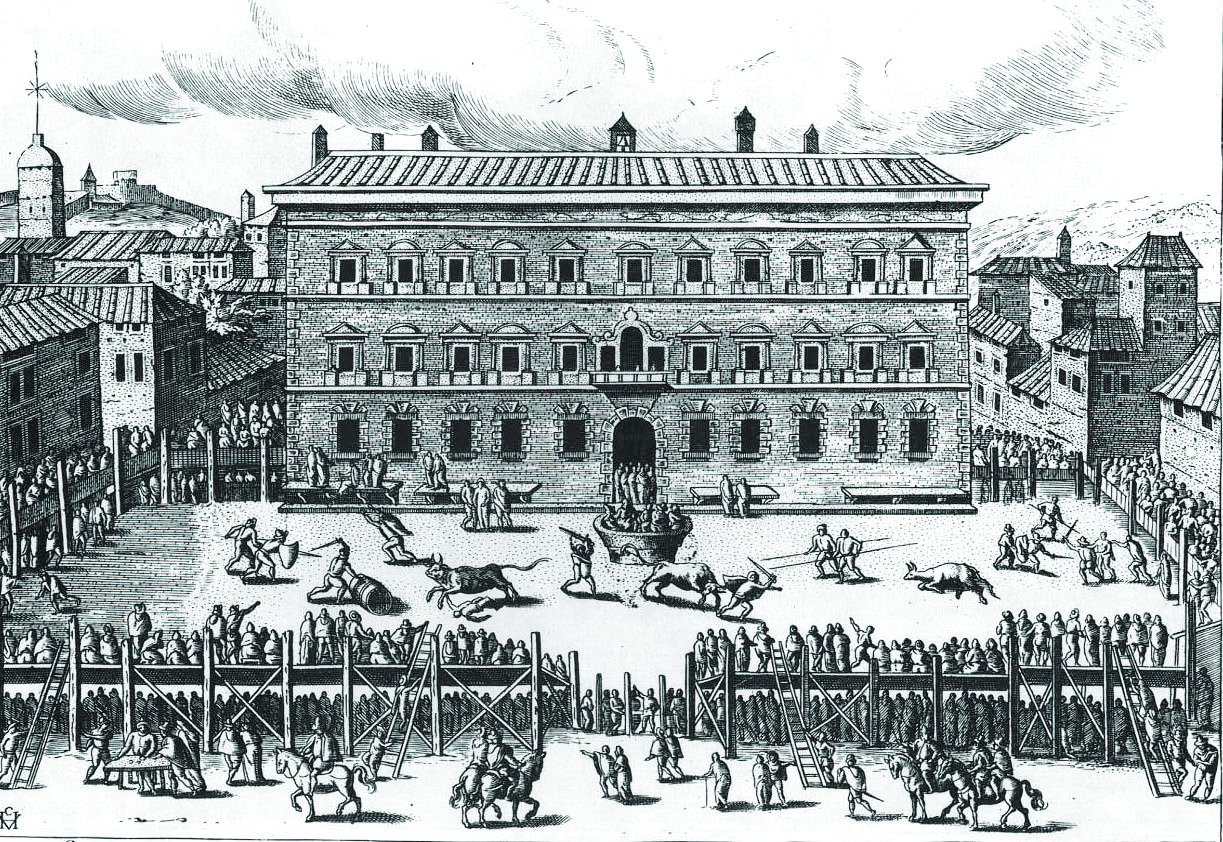

The Capitoline Hill

Michelangelo’s redesign of the Capitoline Hill centers on an ancient bronze of Marcus Aurelius.

On December 10, 1537, Michelangelo stood at the top of the Capitoline Hill, one of the seven hills of Rome, and was granted Roman citizenship in a ceremony full of pomp and grandeur. But the splendor could not disguise the grubbiness of the site. What had once been described as the “golden capitol” had degenerated over centuries into a muddy hilltop, difficult to climb and treacherous to descend. In 1538, Pope Paul III asked Michelangelo to redesign the Capitoline Hill, or Campidoglio, and make it glorious again.

When the papal conclave met in 1534 and elected Paul III, a Farnese pope with strong ties to Rome and big ideas for its renaissance, they chose a man who would become one of Michelangelo’s greatest patrons. Paul III was determined to change the mood of Rome, which had not rebounded from the destruction inflicted by Emperor Charles V’s troops seven years earlier. The coronation of Pope Paul III took on the flavor of a Roman emperor’s coronation, marked by games, tournaments, and pageants. In 1536, he revived carnivale—a celebration leading up to Ash Wednesday and the holy season of Lent. And when Charles V (an ally of the Farnese family and thus now an ally of the papacy) announced he would visit the city, Paul III ordered that the streets be widened and straightened to better handle the crowds expected to turn out to see the man who had previously terrorized those same streets.

Not only was the new pope determined to create a more attractive, safer, and healthier city, he was also convinced that Michelangelo was the man to help him achieve that vision. During the fifteen years of his papacy, Paul worked with Michelangelo to project papal power and live up to their shared humanist ideals through a series of civic projects. Paul’s predecessors had revived Rome as caput mundi, but the Sack of Rome had undermined that status. Paul set out to remind the world that Rome was still the center of civilization. He did so by bringing the city back to its roots.

In ancient Rome, all roads literally led to the Capitoline Hill. It stood at the center of the city, and thus of the empire. During the Middle Ages, the hilltop became the site of public executions; by the Renaissance, what had once crowned an empire was now abandoned and swampy. When Charles V visited Rome in 1536, he tried to ascend the Capitoline Hill, but it was so muddy that he could not get to the top.

When Paul III approached Michelangelo to transform this morass, he was asking the artist to take on both a symbolic and a literal restoration. The project involved defining a safe and accessible entrance to the hill from the city, converting a muddy plateau into a level, paved area, and restoring the once grand structures that sat atop the hill. All this had to be done while respecting the existing buildings, including the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli.

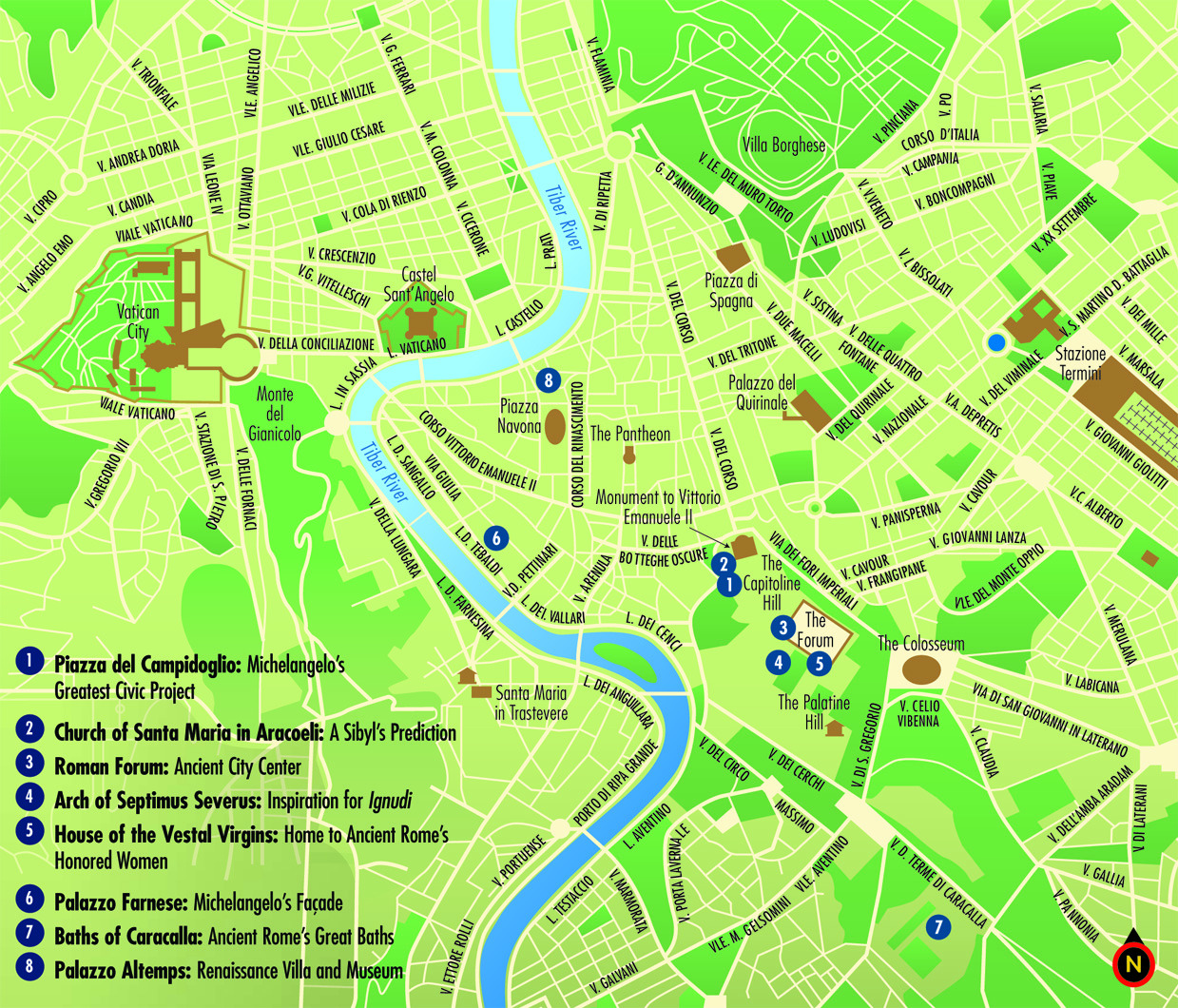

Michelangelo’s plan called for an impressive program of construction that would reinforce Rome’s position as a powerful city. Traditional Roman architects tamed large spaces by marking the center of the space and then designing in a radius around the center. For example, in the center of the Pantheon’s floor is a circle upon which stood a ceremonial brazier where sacrifices were burned. The rest of the building radiates out from that central ceremonial spot. In similar fashion, Michelangelo began by placing a striking object—a statue of Marcus Aurelius, the only equestiran bronze to have survived from the Roman Empire—at the center of the new piazza atop the Capitoline Hill and then designing outward along the piazza’s radii.

The original bronze sculpture of Marcus Aurelius was removed from the

piazza in 1981 because it was being corroded by the weather; it is now

housed yards away in the Musei Capitolini. A full-scale replica stands

on the base Michelangelo designed for the original.

Piazza del Campidoglio.

A Challenging Commission

In the 1 Piazza del Campidoglio, Michelangelo faced a major challenge: the existing buildings. Now, as then, the Palazzo Senatorio and the Palazzo dei Conservatori sit close to each other, but they sit at odd angles, and the ancient church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli looks nothing like the other buildings. Charged with preserving both palazzi and the church, Michelangelo had to devise a means of relating them to each other as well as to the site as a whole. He found the perfect solution in the use of an oval, which allowed him to create a space of symmetry and grandeur from several disparate elements. He pulled everything together with a design that married the old and the new.

The Palazzo dei Conservatori, the seat of the elected city magistrate, featured a campanile (bell tower) that was off-center in relationship to the building supporting it. Michelangelo moved the campanile to the center of the palazzo. He then unified the two palazzi and gave the whole courtyard a sense of balance and rhythm by constructing wide pilasters (rectangular supports that resemble flat columns) on both buildings. Rather than letting the eye focus on the many tiny windows and openings of the building, the pilasters draw the eye up and create a larger, less confusing pattern upon which to focus. To further balance the composition, Michelangelo designed a third building (the Palazzo Nuovo) to mimic the Palazzo dei Conservatori. Together, the three buildings now house the Musei Capitolini as well as Rome’s city hall.

The Piazza del Campidoglio feels like an outdoor room—a design element with which Renaissance Italians were intimately familiar. Much of Italian life takes place in outdoor rooms: the piazza is the center of the neighborhood; the courtyard is the center of a wealthy Italian’s home. The Piazza del Campidoglio became a place for outdoor ceremonies—a role that it still plays. Today the piazza is often filled with wedding parties; Rome’s city hall is one of only two places in the city (the other is at the Baths of Caracalla) where a civil ceremony can take place.

The Piazza del Campidoglio is often bustling with brides, grooms, and their

families. In Italy, unless a wedding ceremony is performed in a Catholic church,

the couple must also conduct a civil ceremony before their marriage is

considered legal.

Michelangelo died before construction on the Capitoline Hill was completed. His friend and protégé Tommaso de’ Cavalieri oversaw the construction and preserved Michelangelo’s vision. One element of the final design—Michelangelo’s oval, star-patterned pavement—was not installed until 1940, during the reign of Benito Mussolini. It is ironic that Michelangelo’s humanist vision of an elegant piazza was completed centuries later by a fascist dictator. Although Mussolini and Michelangelo shared a respect for Italian history and a taste for awe-inspiring architecture, Michelangelo was a committed republican (he designed fortifications for the defense of Florence) and his architecture, unlike Mussolini’s demeanor, was neither overbearing nor self-indulgent.

Humanism

The task of restoring a civic space infused with historic significance called for an architect knowledgeable about the arts as well as politics, science, and history. Michelangelo’s humanist education and philosophy made him the perfect man for the job.

Humanists prized an education in the art and literature of ancient Greece and Rome; they believed that those schooled in the classics would become successful, cultured, and civilized and would use their education to help create a society that would be wisely governed, industrious, prosperous, and pious. Humanism began as an intellectual current among the elite, but it gradually flowed down through the social strata until humanist principles permeated Italian society. Humanist thinking transformed political life, military theory, science, commerce, poetry, and art. Education became de rigueur for women in some social circles; even among women of the lower classes, literacy became more important. The educated woman, however, was stuck. Her knowledge was an end in itself rather than a means to an end, because society frowned upon the idea of a woman working outside of the home.

Musei Capitolini

Pope Sixtus IV effectively founded the Musei Capitolini, the oldest public collection of ancient art, in 1471. The pontiff donated four works to the people of Rome, establishing a tradition that continued through the Renaissance as popes donated treasures long hidden within churches and palaces to the people of the city.

The donated art originally sat in the piazza, open to the elements and on public display. However, as the collection grew and conservators also began to purchase pieces, the art was moved into the Palazzo dei Conservatori, where pieces were arranged in the courtyard and rooms. The museum complex grew and expanded into all three buildings on the piazza and now extends through a subterranean space beneath Michelangelo’s oval courtyard.

Men faced no such restrictions. The consummate humanist was Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519). Da Vinci the scientist analyzed human anatomy, designed flying machines, and invented a steam engine. Da Vinci the engineer prepared plans to build bridges, divert rivers, and besiege cities. Da Vinci the painter produced beautiful, precise canvases that are both distinctive and lyrical. Da Vinci the designer created costumes for theatrical productions and sets for elaborate court festivals.

The Roman Forum

In 1538, the view from the Capitoline Hill was expansive. Sixty-three-year-old Michelangelo could see his home at the foot of the hill and the sprawl of the city all around. But the view toward the Palatine Hill was shocking. Within Michelangelo’s lifetime, and primarily at the direction of his papal patrons, the buildings in the area called the 3 Roman Forum were largely disassembled and harvested for construction material and museum pieces, leaving the skeletal remains of an empire’s crossroads.

Santa Maria in Aracoeli

The 2 church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli was more than just an obstacle for Michelangelo’s construction project on the Capitoline Hill. It marked the spot where, according to legend, a Roman sibyl predicted the coming of Jesus Christ—a moment fusing Rome’s pagan and Christian histories. The Renaissance traveler, looking beyond Santa Maria in Aracoeli, would have seen the convent attached to the church as well as numerous other minor buildings scattered down the hill, spilling out in the direction of Macel de’ Corvi, where Michelangelo lived.

Ancient Rome was an enormous city, and the Roman Forum was its center—the heart of commerce, politics, and religion. As with the place of France and the piazza of later Italy, life in the city revolved around the Forum. Filled with temples, palaces, and civic buildings and surrounded by market areas, the Roman Forum hummed and pulsed.

As the Roman Empire declined, however, so too did the Roman Forum. Eventually, the Forum fell into ruin, becoming known as the Campo Vaccino (“cow pasture”), a popular spot for grazing both cattle and sheep. Olive trees sprouted among the debris, and the air smelled of sage, rosemary, and thyme.

Pope Julius II was one of many who pirated vast quantities of building materials from the Forum. In his zeal to rebuild Rome and exalt the papacy, Julius II ignored the protests of Michelangelo and the painter Raphael, among others, who were upset by the wholesale destruction of the ruins. Workers hauled away marble and metal at an amazing rate, dismantling entire buildings in the space of a month. Ancient marble slabs were ground down to limekiln dust, used to make cement.

Raphael, appointed superintendent of antiquities in 1515, submitted a report to Pope Leo X:

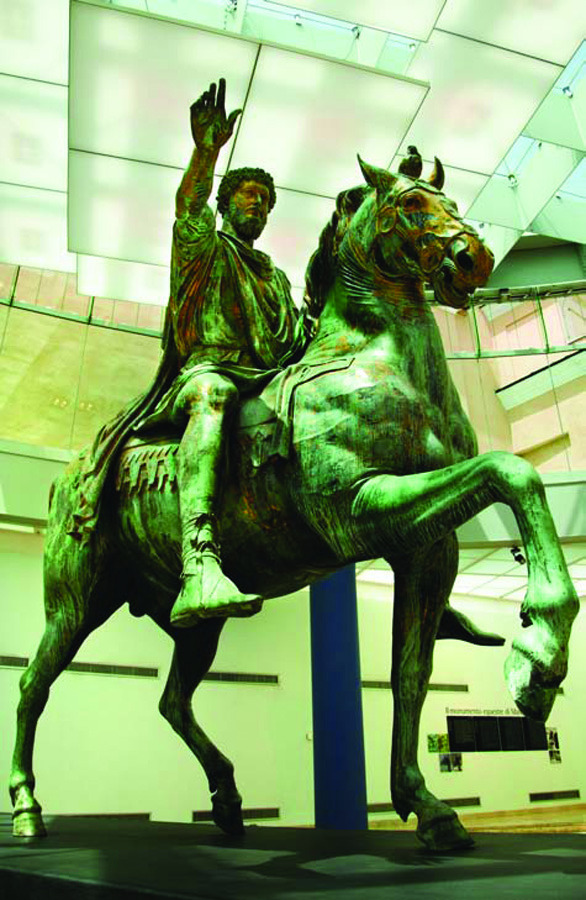

Most of what survived the pillaging survived thanks to one of two circumstances: consecration as a church or burial over time. Built in 203A.D., the 4 Arch of Septimus Severus commemorates the victories of Septimus Severus against the Parthians. The arch was partly buried during Michelangelo’s day, allowing him a close view of the figures at the top of the arch and deterring would-be plunderers. The east face of the arch bears figures that reappear as ignudi in the Sistine Chapel, and the arch itself served as a precedent for Julius II’s tomb.

The ruins of the Forum viewed from the Palatine Hill.

Museums and collectors spirited away most of the marble figures that once graced the Forum. A procession of female figures still lines the atrium of the 5 House of the Vestal Virgins, however, hinting at the kind of decoration that adorned the Forum before it was buried in the sage and thistle of the Campo Vaccino.

Dedicated to the service of Vesta, the goddess of home and hearth, the Vestal Virgins held an elevated religious and social position. Selected between the ages of six and ten from among the daughters of Rome’s patrician families, each of the six virgin priestesses served for thirty years. Thereafter, they could retire and marry, but few left their pampered, comfortable lives, in part because they considered it bad luck to do so.

The ruins of the virgins’ home give a sense of the women’s importance. Among Roman women, the virgins ranked second only to the empress and warranted deference from the entire empire. Their residence, located adjacent to the temple where they served, featured rose gardens, a pool, fountains, and a hall filled with memorials and honors bestowed upon them by thankful citizens. This complex in the crowded and expensive center of the Forum boasted fifty rooms on the ground floor alone, and there were probably two or three floors above. The virgins tended the sacred flame to Vesta, a symbol of the state, and enjoyed all kinds of preferential treatment, including special seats at the theater and the Colosseum. Their vows of chastity, however, were binding, and they faced a live burial in the “field of the wicked” (campus sceleratus) if they broke those vows.

The Vestal Virgins’ lifestyle and social importance declined with the growth of Christianity; by the Renaissance, they had become the subjects of myth.

The Arch of Septimus Severus was once topped by bronze sculptures of

a chariot drawn by six horses, but they have long since vanished.

Michelangelo on Titian

In 1545, Pope Paul III invited the Venetian artist Titian to Rome, where Michelangelo paid him a visit. As he entered Titian’s studio, Michelangelo saw that Titian was at work on Danaë, a painting of a female figure from Greek mythology commissioned by Ottavio Farnese. He liked Titian’s use of color but disliked his soft figures. Titian paid less attention than Michelangelo did to anatomy, and the Venetian’s figures tended to be plump and round rather than muscular and taut. Michelangelo commented, “If Titian ... had been assisted by art and design as greatly as he had been by Nature, especially in imitating live subjects, no artist could achieve more or paint better, for he possesses a splendid spirit and a most charming and lively style.”

Nevertheless, Michelangelo drew upon their example when he painted the quartet of sibyls—powerful, spiritual women—on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

A Palace for Paul III

Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had been orchestrating the construction of the 6 Palazzo Farnese for seventeen years when he was elected pope in 1534. As Pope Paul III, he engaged Antonio da Sangallo to complete the building, making him the third architect to be involved with the project. The least gifted of Donato Bramante’s students, Sangallo was the first Renaissance architect to be trained only in architecture and he devoted himself to his profession. He was the leading architect in Rome from 1520 to 1546. What he lacked as a designer, he made up for in his abilities as an engineer and builder; his designs lacked finesse (and his decorative schemes tended to be fussy, busy, and repetitive) but they have endured the wear and tear of centuries.

A palazzo such as the Farnese was designed primarily as an expression of power and strength, although it also functioned effectively as a comfortable residence. The business of running a large household took place on the ground floor, which contained offices and kitchens. Goods delivered to the palazzo courtyard could easily be unloaded and carried to the larders and storerooms that also occupied the ground floor.

What Italians refer to as the primo piano (the “first floor”)—what Americans would call the second floor—existed to impress, for it was here that wealthy Italians of the Renaissance would entertain. Featuring reception halls and large spaces for public ceremonies decorated with grandiose designs and luxurious furnishings, the first floor showcased the family’s wealth and standing. The primary family quarters also occupied this floor; lesser family members and retainers lived on the floor above. Servants slept in the mezzanines between the floors or in attics.

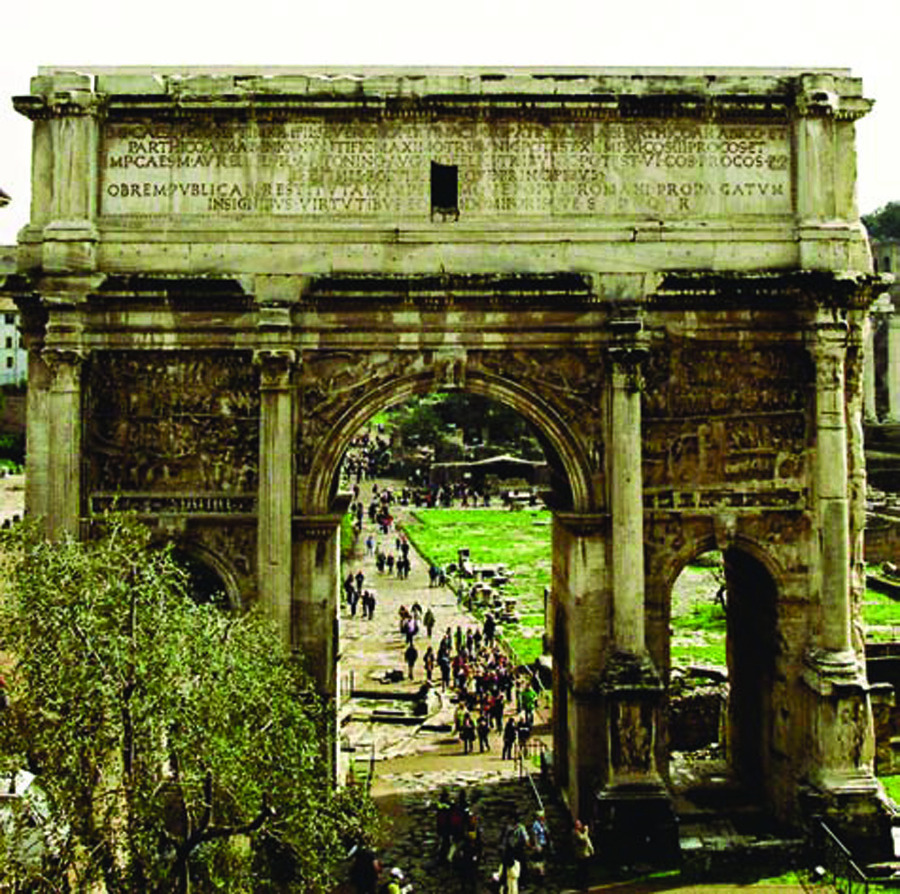

This drawing from the mid-1500s shows a bullfight in front of the Palazzo Farnese. Note the people in the tub; Michelangelo created fountains for

the front of the palazzo using tubs from the Baths of Caracalla.

The death of Sangallo in 1546 brought a halt to the Farnese project as well as to the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica, a project Sangallo had inherited in 1539. Eventually, Michelangelo assumed responsibility for both: he was commanded to take on the building of St. Peter’s, and he won the Palazzo Farnese project in a design contest. By that time, the palazzo’s façade was finished to the base of the third story. Following tradition, Sangallo’s designs called for the third floor to diminish in scale compared to the first and second floors. Michelangelo’s design did not follow suit. He raised the height of the third floor and submitted models for the heavy cornice that was later installed on that same floor. He also changed the central window design. These departures from classical dimensions raised eyebrows among Sangallo’s devotees, for the third floor would now dominate the building design, even though, as the living quarters for lower-status family members, the third floor of a building usually received the least aesthetic consideration. In the end, Michelangelo’s treatment of the third floor made the Palazzo Farnese the most distinctive and imposing building on the piazza.

Michelangelo’s passageway over Via Giulia.

Michelangelo’s dreams for the Farnese were grand. In 1546, a sculpture of Hercules with a bull was discovered in the 7 Baths of Caracalla. Inspired, the artist designed a fountain featuring the treasure for the front of the Farnese. He proposed extending the palace’s grounds all the way to the river and across, uniting the Palazzo Farnese with the Villa Farnesina on the other side and creating a grand family estate with lush gardens and antiquities dotted throughout the grounds. The grander vision was never executed, however, and all that remains of Michelangelo’s dream today is an arched walkway across Via Giulia.

In the piazza today sit two enormous fountains made from marble tubs. The tubs came from the Baths of Caracalla and sport fleurs-de-lis—the Farnese family symbol—spouting water. The Palazzo Farnese now houses the French Embassy and is closed to the public, but the Piazza Farnese hums with activity and hosts several charming cafes with excellent views of Michelangelo’s design. Just a block away, the bars and pizzerias of the Piazza di Campo dei Fiori are less dignified but make for a pleasant place to watch people shopping at the open-air flower market.

The Baths of Caracalla

Located not far from the Circus Maximus, the Baths of Caracalla were built by the Emperor Caracalla and dedicated in 216A.D. Among the smaller of Rome’s bathing complexes, the buildings could accommodate sixteen hundred bathers. The water ran from a specially constructed spur of the Aqua Marcia. They fell out of use after the Goths cut off the water supply in 537, but in their glory days, the baths were filled with fine statuary and mosaics, frescoed walls, a variety of bathing facilities, and a gymnasium. Baths functioned both as public meeting spaces and as places for entertainment. Emperors seeking to curry favor with the citizens of Rome often built baths—each complex outdoing the last—and many emperors opened the baths for free, though fees for bathing were never high, because bathing was highly regarded by the ancients.

During the sixteenth century, excavations of the Baths of Caracalla revealed numerous beautiful works of art, most of which ended up in the Farnese family collection. Today, the ruins attest to the scale of the Roman Empire’s passion for bathing.

The tubs used in the fountains in front of the Palazzo Farnese came from the

Baths of Caracalla.

Palazzo Altemps

The Palazzo Farnese is closed to the public, but the 8 Palazzo Altemps offers people the chance to visit a beautiful upper-class Renaissance residence. Frescoes grace the ceilings and walls of many of the rooms—especially in the public areas of the primo piano. The courtyard once provided a space for theatrical performances. Today, the Palazzo Altemps houses an impressive collection of ancient sculpture, including many pieces celebrated and imitated during the Renaissance.