Chapter 8

St. Peter’s and Beyond

St. Peter’s Basilica

welcomes millions

of visitors each year.

Michelangelo resisted getting involved with the St. Peter’s Basilica project as long as possible, despite pressure from several popes and fellow artists. Enormous and expensive, construction of a new St. Peter’s Basilica had been the obsession of every pope since 1506, when Julius II decided to replace the old St. Peter’s so that his tomb, a monument designed by Michelangelo, would fit inside.

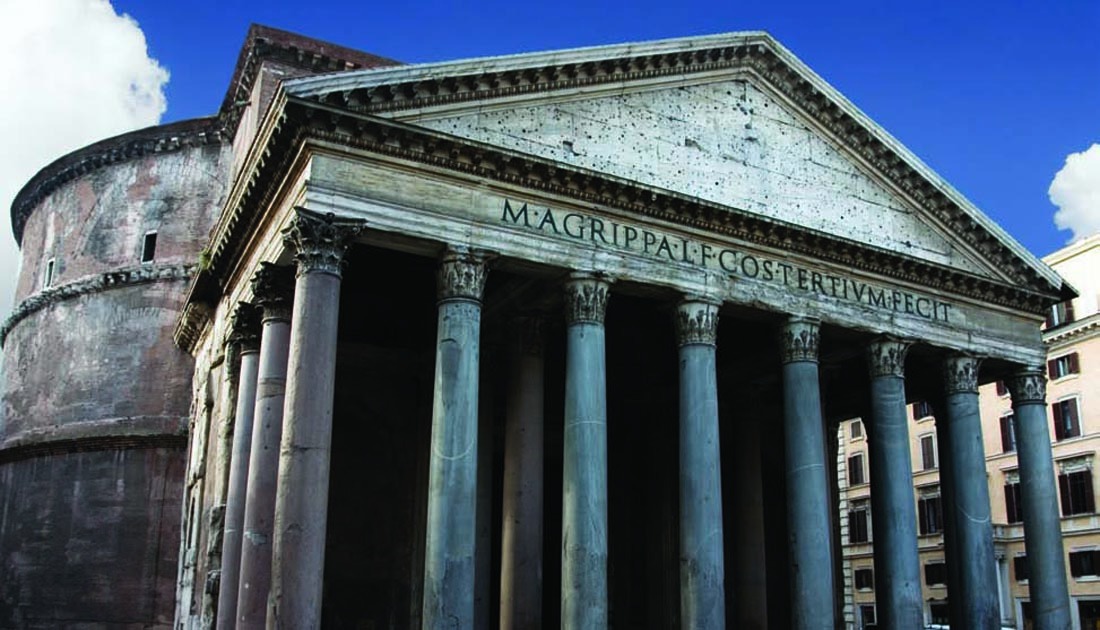

The original St. Peter’s, a building Michelangelo liked and admired, sat on marshy ground in the Vatican—a spot chosen by Emperor Constantine. Julius II dreamed of replacing the fourth-century basilica with a building that would symbolize the very considerable power, wealth, and authority of the Renaissance church, knowing that he would not live to see its completion.

The new St. Peter’s would forever change the scale and tone of ecclesiastical architecture. Yet the costs of building such an enormous structure would also contribute to the division of Western Christianity and an enduring reduction in papal power.

Ecclesiastical Architecture

Roman parish churches—today there are more than six hundred—played a variety of roles during the Renaissance. They offered a venue for the most important rituals of life: birth, first communion, marriage, and death. According to Catholic doctrine, the church in all its guises (e.g., clerics, buildings, and ceremonies) functioned as the “earthly manifestation of Christ’s incarnation” and mediated between God and the people; without the church, people could have no contact with God.

In an uneducated and illiterate society, parish churches also offered entertainment. With holy water and the Eucharist, saints and their relics, paintings and sculptures, and a calendar full of colorful festivals, churches provided congregants with the pomp, ceremony, and spectacle their daily lives usually lacked.

While living in the neighborhood of Macel de’ Corvi, Michelangelo probably worshipped at the parish church of 1 Santa Maria di Loreto, which adjoined the small courtyard his house faced. Small but impressive, the church was built in the early sixteenth century by Antonio da Sangallo the elder. The dome was added later, in 1573, by Jacopo del Duca, a devotee of Michelangelo.

The daily experience at mass in the 1500s was not necessarily one of pious reverence. Most of the service was conducted in Latin, a language spoken only by the educated elite, so most members of the congregation were left to their own devices. During sermons, which could stretch for hours, congregants behaved much as they would on the street: knitting, begging, spitting, joking, heckling, swearing, sleeping—even firing guns.

Physically, churches stood in the middle of their communities. Most neighborhood churches opened up onto a piazza. During festivals and pageants to celebrate saints and martyrs, politicians campaigned, merchants hawked their wares, and vendors sold all kinds of food. In Renaissance Italy, the sacred life could not be separated from the secular.

This was true in part because Christian architecture had grown from secular roots. Until the fourth century, Christians had been forced to gather in private, sometimes secret, places to worship. When Constantine announced his conversion to Christianity, he began to build sacred spaces and constructed three impressive churches in Rome: San Giovanni in Laterano, San Pietro in Vaticano (St. Peter’s), and San Paolo fuori le Mura. But the larger Christian community did not have the kind of money that Constantine did to build churches. Thus, they continued the Roman tradition of reusing materials when creating their sacred spaces. They recycled something else, too: the architecture of Roman basilicas.

Santa Maria di Loreto was just steps away from Michelangelo’s home. The church’s

dome was inspired by the dome that Michelangelo designed for St. Peter’s.

The basilica, constructed in the center of a city as a place to conduct business transactions, anchored the ancient Roman economy. All basilicas have the same basic proportions, being twice as long as they are wide. They also adhere to roughly the same internal design, with rows of columns forming aisles and delineating smaller areas to each side. The Christian church adopted this basic floor plan—sometimes even turning ancient basilicas into churches. Shops in ancient structures became side chapels and altars in Christian buildings. Thus, the construction techniques of ancient Rome became the standard for Christian construction, and the basilica became the foundation of Christian architecture. There are now thirty-one basilican churches in Rome alone.

Christian Relics

During the Roman Empire, Christians often established communities of faith—and later built churches—in locations where saints and martyrs had died or were buried. The remains of these venerated figures came to represent a conduit between the living and God and served as a reminder of the believer’s task in life. Churches competed ardently for relics, either homegrown or imported, because crowds were drawn to relics. And crowds of pilgrims and locals conferred fame and status on a church as well as on its clergy.

Roman churches boast a wide range of relics. Although many of the most cherished are held at the Vatican—according to tradition, the remains of St. Peter himself rest underneath the altar in St. Peter’s Basilica—other churches also possess significant relics. 2 San Silvestro in Capite, with an altar designed by Michelangelo, houses what is claimed to be the head of St. John the Baptist as well as the face of Christ on a veil. Santa Maria degli Angeli contains a chapel of relics where the remains of martyrs associated with the Baths of Diocletian are housed. Santa Maria Maggiore has the crib of the Christ Child, and San Paolo alle Tre Fontane sits on three springs that, according to tradition, emerged when Paul was beheaded at the site.

The Pantheon

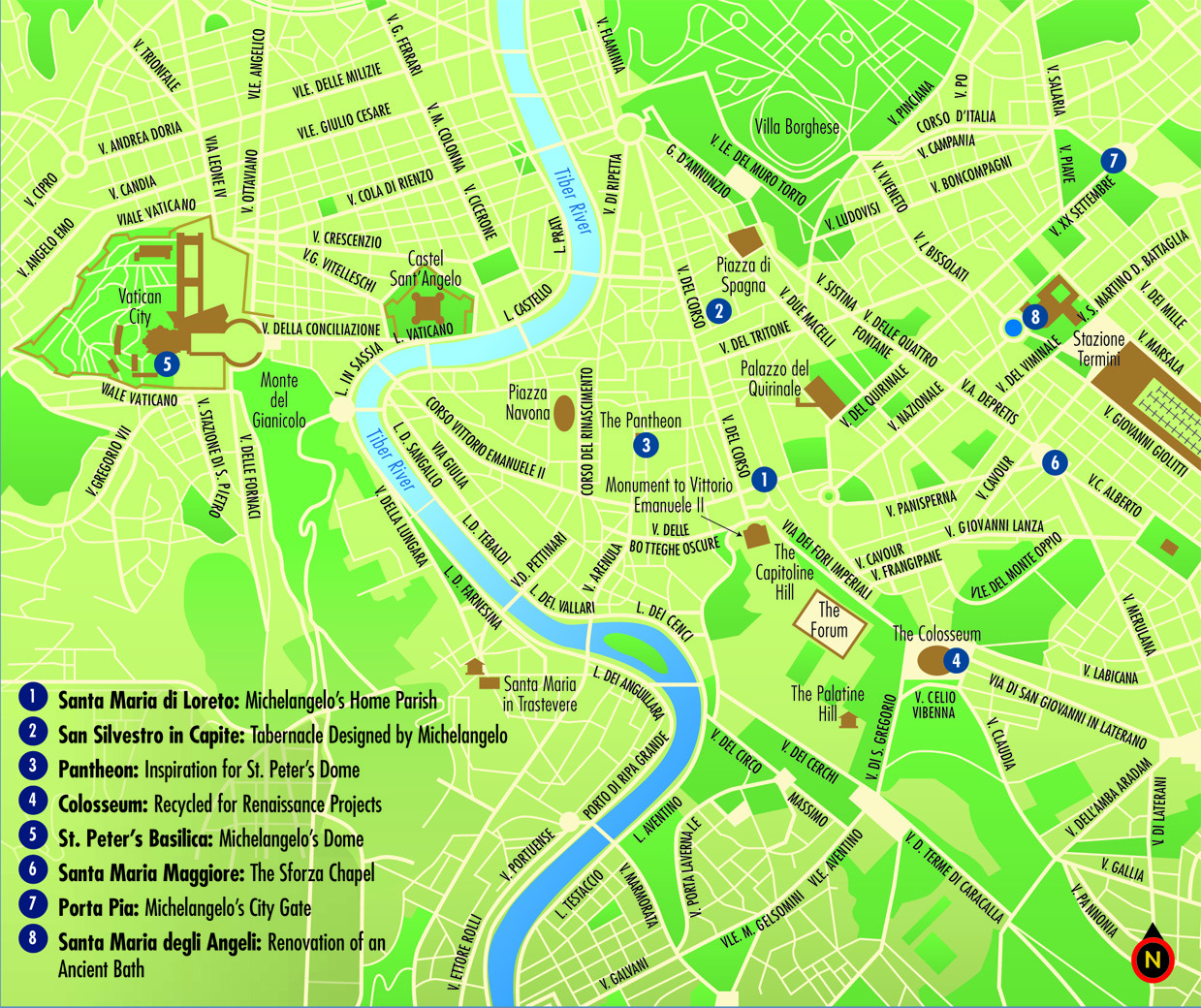

Michelangelo based his designs for St. Peter’s dome on two sources of inspiration. One was a church in which he had played and studied as a boy: Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Florence’s Duomo was the first dome built after the fall of the Roman Empire; designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, the dome was completed in 1436. Michelangelo’s other inspiration was in Rome and was considerably older: the 3 Pantheon.

Although not a basilica, the single most aesthetically powerful building of ancient Rome was the Pantheon. Michelangelo, an ardent admirer of the Pantheon, attributed its power to disegno angelico e non umano (angelic and not human design). It was consecrated in the seventh century as a Christian church, Santa Maria Rotunda, but the building remains better known the world over by its pagan name.

Since 25B.C., and perhaps before, the site on which the Pantheon stands has been sacred. Agrippa, a statesman and general in the first century B.C., erected a rectangular pantheon (literally, a place of worship honoring all gods) on the site. However, Agrippa’s structure burned down—twice.

Emperor Hadrian erected a replacement that was dedicated in 126A.D. He inspired centuries of confusion by putting this inscription on his new building: M•Agrippa•L•F•Cos•Tertium•Fecit. Translated, it reads, “Marcus Agrippa, the son of Lucius, three times consul, built this.” (Hadrian, in a rather un-emperor-like fashion, often neglected to put his own name on buildings he constructed.) Thus, for centuries the Pantheon was thought by many to be two hundred years older than it actually is. The bricks used in the building’s construction, however, reveal the truth. They bear stamps dated to Hadrian’s reign.

In 609, Pope Boniface IV consecrated the Pantheon as a Christian church “after the pagan filth was removed.” That “pagan filth” included sculptures of Mars, Venus, and a deified Julius Caesar as well as caryatids—draped female figures that functioned as columns and bronze figures on the pediment over the porch.

Even after the building’s consecration, Romans did not hesitate to alter their greatest relic. In 663, Emperor Constans II melted down the gilded bronze roof tiles, which had reflected the sun’s radiance. Pope Pius IV restored the bronze pilasters at the entrance but had the original doors gold plated. Despite all the plundering, the Pantheon was ultimately saved thanks to its consecration. Of all the ancient structures in Rome, it is the best preserved.

The Pantheon has been in continuous use—as a temple, a church, and a tomb—since its construction nearly two thousand years ago.

The Pantheon has remained a symbol of the beauty and accomplishments not just of Rome but of Italy as a whole. When Raphael died in 1520, he was buried in the rotunda, in the building he admired most. Vittorio Emanuele II, the first king of a united Italy, was also buried in the Pantheon, his internment signifying the sacred, historical, and political continuity of the country.

An Impressive Inspiration

The two most distinctive elements of the Pantheon are its dome and its oculus. For the ancient Roman worshipper, the oculus (a circular hole in the roof) connected the world of the gods with the human world. The sun, the eye of Zeus, peered through the oculus, tracking light across the floor and marking the days and the passing of the year. The gods, Roman cosmology, and the emperor were all intimately linked, and the Pantheon embodied that link.

The sun shines through the

oculus of the Pantheon.

But it is the Pantheon’s dome that has always most impressed visitors. A symbol of permanence and divinity, the dome has been associated with sacred architecture since its construction. The dome uses a compression system of buttresses to carry the weight of five thousand tons of concrete. The concrete itself was delicately engineered to be progressively lighter as the poured panels came closer and closer to the oculus.

As Renaissance artists and architects looked to the ruins of ancient Rome for instruction and inspiration, they tried to divine—and then to copy—the mathematical formulas that their predecessors had employed to construct such marvels. But even many of the simplest techniques known to the ancients had been lost in the intervening centuries and remained hidden from view. The recipe for concrete, for example, had been lost, and Brunelleschi was left to construct his dome in Florence out of bricks and mortar.

Unlike many of his colleagues, Michelangelo did not seek a mathematical solution to architecture, and instead adopted a more anthropomorphic approach. In studying buildings like the Pantheon, he looked at the interactions between the buildings and the people who occupied them. “It is certain,” Michelangelo wrote, “that architectural members depend on the same rules as those governing the limbs of men.” He attributed the design of the Pantheon to “angelic” design not because it followed particular rules, but because it inspired a particular emotion and exemplified a relationship between the human figure and the building itself—a relationship he would try to recreate in his design for St. Peter’s Basilica.

The Colosseum

The 4 Colosseum dominated Rome—until the new St. Peter’s began to soar across the river. Emperor Titus inaugurated the Colosseum as a place of public entertainment in 80A.D. Built to hold fifty thousand spectators, the Colosseum was intended as a place of public entertainment and gathering. It enjoyed nearly four centuries of use, beginning with one hundred days of games held at its opening.

On the first day of games in the Colosseum, five thousand animals were slaughtered in a riot of brutality and bloodlust. Although stories of Christians being fed to the lions in the Colosseum are fiction (those kinds of events happened at the Circus Maximus and elsewhere), the Colosseum did regularly host bloody gladiatorial battles. The floor of the arena was covered in sand to absorb blood, and underneath the floor a network of tunnels and rooms hid animals and people waiting to appear. The floor could even be flooded with water for mock marine battles. While the games were being played, spectators sat in relative comfort. Seats were assigned, and spectators ate and drank as they watched the events on the arena floor. A system of canvas shades at the top of the building kept the sun at bay.

Eventually, however, the Colosseum was abandoned. It was stripped of its metal fittings, and much of its stone ornamentation and decoration was reused in other building projects, including the Barberini and Canalleria palaces, the Ponte Sisto, and St. Peter’s Basilica.

The best seats in the Colosseum were reserved for the emperor, his

guests, and the Vestal Virgins, but tickets were inexpensive—and

sometimes free—so that everyone could enjoy the entertainment.

Note the now-exposed passages that were under the arena floor.

A Skillful Architect

When Donato Bramante (1444–1514) moved to Rome in 1499, he was already a well-established architect in other parts of Italy. Born near Urbino, Bramante had trained as a painter and, like most other artists of the Renaissance, had been educated in various media, including architecture. His work in Rome would transform and define the architectural styles of an entire generation.

After Michelangelo suggested to Julius II that the roof of St. Peter’s would need to be raised to encompass the pope’s tomb, Julius decided that a new church might be a better idea. He held a design contest to choose the architect, and Bramante won. In 1506, while Michelangelo was in Carrara choosing marble for the pope’s tomb, the foundation was laid for the new St. Peter’s Basilica.

From the start, the construction project was enormously expensive and time-consuming. Initially, there was some confusion as to whether the old church was to be remodeled or demolished. In 1512, Julius II issued a papal bull promising the completion of the new St. Peter’s, and the remnants of the old church were destroyed.

Although the old St. Peter’s Basilica was not a

monumental structure—in fact, it was not even the

largest church in Rome—it resembled a village

with living quarters, military outposts, a piazza,

and homes surrounding the church. In many ways,

Vatican City is much the same today.

While Michelangelo was at work in the Sistine Chapel, the destruction he saw across the way disturbed him greatly. He approached the pope, expressing his disapproval of Bramante’s ruinous tendencies. Where Michelangelo would have carefully saved columns and capitals, Bramante (nicknamed “Maestro Ruinate”) had simply and violently pulled them down. After Bramante’s death, a satire was written that depicted him in heaven: the architect wanted to demolish everything there and build a new and better one—with access roads.

When Bramante began construction on the basilica, he started at the center of the building—the altar—and worked outward in concentric circles. Given that construction would take centuries, this approach would ensure that the building would grow uniformly from the core out. Beginning with four central piers and four buttressing arms, Bramante slowly began to raise a new building.

In 1514, at the age of seventy, Bramante died—just as the project was starting construction. Raphael, who had worked under Bramante’s tutelage, was the logical replacement. But Raphael died just six years later, and in his wake came a succession of architects—each a little more removed from Bramante and his vision. Michelangelo watched from afar as the building took shape, never wishing to be involved with such a mammoth task.

Michelangelo and St. Peter’s

Construction on the new 5 St. Peter’s continued for decades while Michelangelo worked on other commissions in Florence and then again in Rome. When Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, the latest in a succession of architects of St. Peter’s, died in 1546, Pope Paul III chose Michelangelo to replace Sangallo.

Michelangelo accepted the job reluctantly. He knew he could do it—and do a better job than Sangallo. But ultimately he accepted the commission because he saw it as another opportunity to use his gifts to glorify God.

Michelangelo knew that wresting authority away from Sangallo’s followers would be a battle, as it was proving with the Palazzo Farnese, another of Sangallo’s projects. In order to defuse some of the opposition to his appointment—and to preserve a measure of independence from the papacy—he refused the usual compensation. This arrangement also allowed him to continue to work on the Palazzo Farnese, the Campidoglio, and other projects as they came up. He did acquire a contract, however, giving him all of the ferry tolls taken on the river at Piacenza.”

The Church That Provoked a Revolution

In March 1517, Pope Leo X issued an order to sell indulgences in order to finance the continued construction of St. Peter’s. An indulgence excused a sinner from doing penance for sins committed. Because the church needed money, Leo X allowed the sale of indulgences in advance. In other words, people could pay for sins they had not yet committed.

Martin Luther, who had been shocked by Rome’s poverty and immorality when he visited in 1510, was so outraged by Leo X’s decision that he publicly protested, nailing a litany of complaints about the Catholic Church and a program of reforms to the door of his parish church in Wittenberg, Germany. One of Luther’s primary concerns was the construction of St. Peter’s. “Why does not the pope whose wealth is today greater than the riches of the richest build just this one church of St. Peter with his own money, rather than with the money of poor believers?”

The Reformation had begun.

“Upon This Rock I Will Build My Church

Scholars and theologians have contemplated the question of St. Peter’s final resting place for centuries. The Gospels never refer to Peter’s martyrdom or his presence in Rome. Rome has claimed to house St. Peter’s remains since the first century A.D., however, and the Catholic Church has always regarded him as the first pope, for Jesus proclaimed of him, “Upon this rock I will build my church.” The inscription around the drum of Michelangelo’s dome recites these words in six-foot-tall letters.

Peter is generally believed to have died at the hands of Nero in a massacre of Christians, who were treated as scapegoats for the fire that destroyed much of Rome in 64A.D. On the site later occupied by the Vatican stood a circus (a track for chariot races and other amusements) where Nero tortured and killed his prey.

According to tradition, Peter was buried in a nearby necropolis. When Constantine built the first St. Peter’s, he filled in the necropolis to create a solid foundation for his new basilica. That church, in turn, was demolished to make way for the new St. Peter’s.

The hill on which the Vatican stands has long been a sacred place. The Etruscans celebrated rituals there between 700 and 500B.C. The ancient Romans built myriad temples on the hill, named for the “vates,” or holy seers, who interpreted the moans and groans of the gassy, snake-infested swamp. When the old St. Peter’s was destroyed, workers whispered about the “curse of St. Peter” and were terrified to unearth ancient, pagan relics during the laying of the new foundation. The terrorized workers thought the pagan relics were cursed.

In the mid-twentieth century, Pope Pius XII (1939–58) secretly authorized excavations underneath the altar in St. Peter’s in hopes that Peter’s remains might be identified. For ten years archaeologists labored covertly; they announced their findings in 1951. They had found St. Peter’s tomb. Decades of bitter academic controversy ensued, with scholars ridiculing the archaeologists’ methods and discoveries, while the archaeologists fought among themselves publicly.

Do the altar of St. Peter’s and Michelangelo’s dome sit atop the remains of St. Peter? During the papacy of John Paul II (1978–2005), tours of the scavi (excavations) made no mention of St. Peter. However, under Pope Benedict XVI, archaeologists claiming to have unearthed the saint’s remains have found a more sympathetic ear.

So, although to most people it looked like he was not being paid for his work at St. Peter’s, he was in fact making money.

Michelangelo had been partial to the old St. Peter’s, but he recognized the value and beauty in Bramante’s plan. About Sangallo’s design, he wrote:

Michelangelo contended that if Sangallo’s design were to be implemented, the Pauline and Sistine chapels—among other buildings—would need to be destroyed. He had just completed frescoes in both chapels, so he had a considerable stake in seeing them preserved. Neither Michelangelo nor Sangallo’s disciples would back down until finally the pope intervened, giving Michelangelo complete control over both the design and the people working on the project.

A Change in Plans

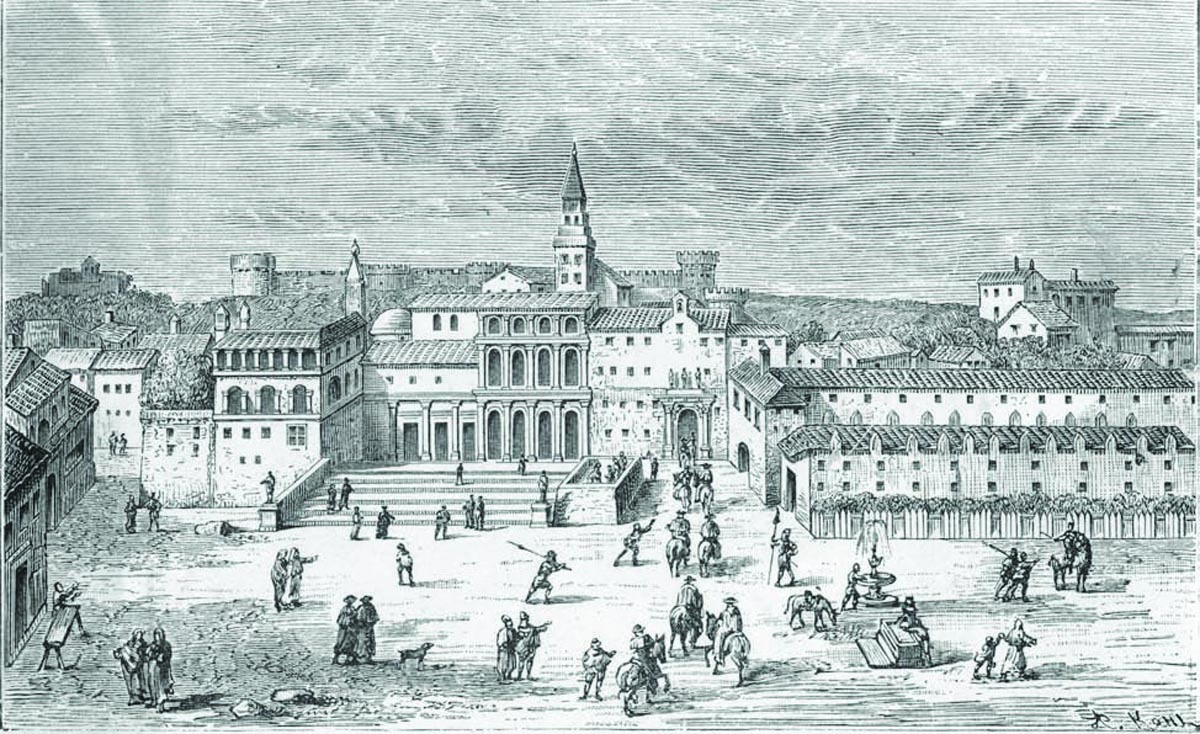

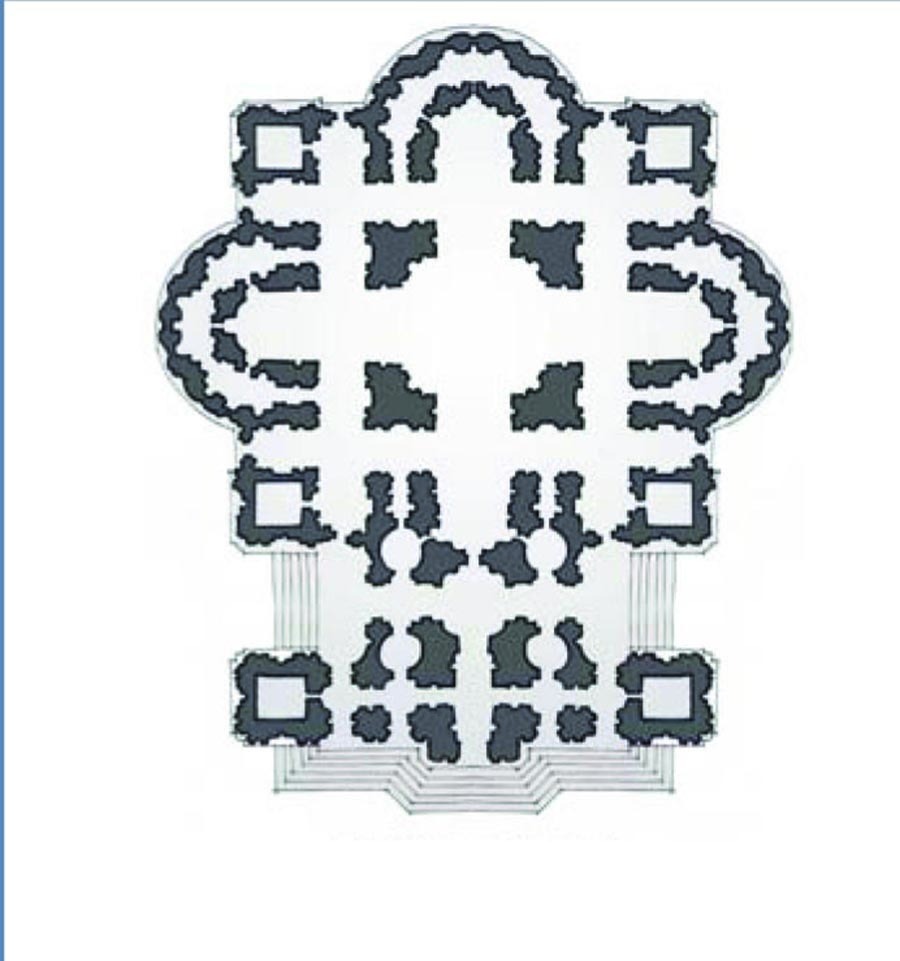

Bramante’s design, a cross inscribed in a square with a dome like that over the Pantheon, reflected the Renaissance architect’s interest in fundamental shapes and proportions. But his original design was diluted by subsequent architects. Sangallo in particular added fussy and uninspired designs to the building, completely losing Bramante’s sense of style. By the time Michelangelo came to the project, he faced a partially constructed building lacking cohesion. Michelangelo returned to Bramante’s original design. He wanted to keep the inner ring where Bramante had begun construction, but he peeled back the layers Sangallo had added. As with the Palazzo Farnese, Michelangelo unified the plan. He stripped the structure down to the original cross-and-square design, then set about installing the dome.

Bramante had designed a dome much like that of the Pantheon: a hemisphere inscribed into the cube of the building. Michelangelo recognized the engineering impossibility in the design: Bramante’s dome was simply too flat to be self-supporting using the construction techniques of the day. In 1547, Michelangelo sent a letter to his nephew Lionardo requesting the measurements for the dome Brunelleschi had constructed in 1436 on the Duomo in Florence.

Family Pressures

By the time he started work on St. Peter’s, Michelangelo was in his seventies and suffering from kidney stones. His age and illness did not prevent him from continuing a lifelong occupation, however: corresponding with his family.

Among those to whom he wrote was his nephew Lionardo, a flighty young man who lived in Florence and stood to inherit much of the childless Michelangelo’s fortune. In 1550, Michelangelo sent a letter to Lionardo acknowledging a gift of wine the young man had sent and asking that he send along some papers from Florence. “On the matter of [your] getting married,” Michelangelo wrote, “there is no more talk, and everyone tells me I should give you a wife, as if I had a thousand in a sack. I have no way to give thought to it, because I have no knowledge of the citizens. I should be very glad if you were to find one, and you must, but I can do nothing more.”

Michelangelo patiently explained to his family, time and again, that he was too busy in Rome to return to Florence. Yet his family continued to lure him home with gifts of pears, cheeses, and other Florentine goods that Michelangelo missed.

Working with clay models, Michelangelo changed his design as the building rose. He worked with the space in the same way that he worked with stone, shaping the interior space of the church rather than prescribing the container around it. In his mind, the building was a container for a space rather than an end in itself. He changed the type of stone he planned to use and the size of architectural elements as he saw the space grow.

Although Michelangelo produced models for various elements of St. Peter’s, he kept the overall plan for St. Peter’s a secret, even from his friends. But his advocates realized that the architect would not live forever, and in the interest of preserving his vision, they begged him to produce a full model. Michelangelo resisted for several reasons. To do so would be, in part, to acknowledge his own mortality. In addition, it would also commit him to a design that could not easily be changed.

Finally, in 1548, he relented. He knew that the construction of St. Peter’s would take centuries. He wanted to accomplish enough within his lifetime that his vision for the building could not be changed—setting the construction down a path that could not be reversed. The model, which began with clay studies, took three years to construct.

In 1549, when Michelangelo was eighty-four, Giovan Francesco Lottini, a papal insider, wrote, “Michelangelo Buonarroti is in fact so old that even if he wished he could not move more than a few miles, and for some time now goes little or rarely to St. Peter’s. Other than which, the model will need many months to complete it, and he is under the obligation, and the desire, to finish it."

Scholars argue over the degree of Michelangelo’s influence on St. Peter’s as it exists today, but no one can dispute that his design gave a solid center to a building process that was floundering and that those who came after him respected his work. The dome that soars over Rome today is largely as the artist envisioned it. However, the portico he designed for the front—resembling the Pantheon—was never constructed. Instead, Carlo Maderno (1556–1629) lengthened the nave to form a Latin cross and added the façade. The interior reflects the contributions of seventeenth-century architects and a shift from the classical designs of the High Renaissance to the Baroque. After all, the nave was constructed a century after its foundation was laid—which allowed plenty of time for an evolution in taste.

Changing Plans

Each architect who worked on St. Peter’s modified the plans. Bramante’s original Greek cross was relatively simple and open, though very large. As construction began, his plans evolved to include more structural support as he anticipated the weight of a dome overhead. Sangallo’s design for an elaborate Latin cross created many small, isolated spaces within the large church. When Michelangelo took over the project, he destroyed much of the construction done under Sangallo. His design, the simplest of all, created large, open spaces for worship surrounded by massive piers and walls to support the enormous dome overhead.

Donato Bramante

1506

Donato Bramante – Baldassari Peruzzi

Before 1513

Antonio da Sangallo

1539

Michelangelo Buonarroti

1546 – 1564

Bernini’s Baldacchino

In 1623, as work on St. Peter’s neared completion, Pope Urban VIII commissioned a baldacchino, a canopy for the altar. Bernini’s design was the only one submitted that was appropriate for the scale of Michelangelo’s dome, under which it was to sit. Completed in 1633, the gilded baldacchino rises nearly one hundred feet in the air and is constructed of a thousand tons of bronze—decorations from the Pantheon melted down.

With a 100-foot-tall baldacchino, 450-foot-tall dome, seven-foot-tall cherubs, six-foot-tall letters, and figures of saints that are

almost twenty feet

tall, everything in

St. Peter’s is on a

large scale.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), a Baroque-era sculptor, architect, and painter, shaped the exterior of St. Peter’s, defining the piazza in front. A double colonnade of 284 columns delineates Piazza San Pietro and welcomes visitors to the Vatican. In the words of the nineteenth-century English poet Robert Browning, “Columns in the colonnade/With arms wide open to embrace/The entry of the human race.”

Michelangelo’s Last Patron

When Pius IV was elected in 1559, Michelangelo was eighty-five and still supervising the construction of the Campidoglio and St. Peter’s from his home at Macel de’ Corvi. He would send notes up to the Vatican with a variety of instructions and comments. One note, for instance, complained, “You are aware I told Balduccio that he should not send his lime if it wasn’t good. Now having sent poor stuff, which must be taken back without any question, one may believe that he had made an agreement with whoever accepted it.”

Under Pius IV, the aging architect took on three more projects: a chapel at Santa Maria Maggiore, the Porta Pia, and the design of Santa Maria degli Angeli.

The church at 6 Santa Maria Maggiore dates to the fifth century, though the building has changed much over the years. In 1560, Michelangelo designed a small, oval-shaped chapel for the Sforza family; it was constructed after his death. It is now used for midday worship services and offers a simple, light space for meditation in the midst of an enormous structure bustling with tourists and pilgrims.

Piazza San Pietro features two large fountains as well as an ancient Egyptian obelisk brought to the city when the Romans conquered Egypt.

Visitors can take an elevator to the roof level of St. Peter’s and then climb 320 steps inside the shell of the dome to reach the top—and the best

view of Rome in the city.

In March 1561, Pius IV asked Michelangelo to design a new gate for the city. Michelangelo presented him with three separate designs, and the pope chose the least expensive. The 7 Porta Pia was not part of the city’s defenses: it faced into the city rather than away, standing as a purely ornamental reminder to those departing that they were leaving the sanctity and protection of Rome.

Snow in Summer

According to legend, the Virgin Mary appeared to Pope Liberius in a dream on August 4, 352, telling him to build a church on the Esquiline Hill. She said he would awake to snow on the hill outlining the design. The first church on the site of the Santa Maria Maggiore was called Santa Maria della Neve (“of the snow”). Each year on August 5, the church brings out snowmaking machines to celebrate the miraculous snowfall, attracting children from all over the city in the heat of the summer.

Constructed between 1561 and 1565, the gate was left unfinished after Pius IV’s death. In the nineteenth century, it was damaged by lightning and reconstructed. The top story, designed by Virginio Vespignani, was added in 1853 during reconstruction. Today, the Porta Pia houses the Museo Storico dei Bersaglieri, a museum of military history.

The Porta Pia.

Pius IV also wanted a large, impressive church along Via Pia, near Michelangelo’s Porta Pia. He approached Michelangelo about designing one. In an unusual move, the artist ended up transforming a room in the Baths of Diocletian, an ancient public bathing complex that had fallen into ruins, into a church.

As a humanist, Michelangelo respected the ancient ruins that dotted Rome. He was practical, though, and wanted to save money, for the pope’s coffers were not as full as they once had been. Today, 8 Santa Maria degli Angeli hardly resembles Michelangelo’s original design. In the eighteenth century, architect Luigi Vanvitelli remodeled the church, moving the altar and adorning the walls with elaborate decorative elements. But the simplicity that Michelangelo desired exists—especially on the building’s exterior, which maintains the look of a Roman ruin.

Working on architectural projects using advisors in the field to supervise the progress gave Michelangelo welcome reason to spend most of his time at home; but, though he was in failing health and reluctant to travel, his commitment to his art did not diminish. As he told Lionardo in a letter in 1557, “As for how I am, I am ill in body, with all the ills that the old usually have ... for if I left the comforts for my troubles that I have here, I wouldn’t have three days to live, and yet I do not ... nor would I want to fail the construction of St. Peter’s here, nor fail myself.”

The Baths of Diocletian

Between 298 and 306A.D., Emperor Diocletian built the largest baths in ancient Rome. Covering more than thirty acres, the baths were a place not only for bathing and gossiping but also for sporting activities and public lectures. A trip to the thermae was an important part of daily life for the ancient Roman, and access to the baths was generally inexpensive or free.

Roman bathing complexes consisted of a variety of rooms, most named for the temperature of the water provided there. The calidarium offered patrons a hot bath; the tepidarium was a warm room for lounging; and the frigidarium gave visitors the chance to cool down. The piscine contained a swimming pool. Attendants and slaves staffed each room, pampering guests with oils, massages, shaves, and personal attention. Roman baths typically featured an elegant array of public artworks: frescoes, statues, fountains, and mosaics.

During the Renaissance, artists visited the disused Baths of Diocletian to study the decorative schemes on the walls, while treasure hunters came to unearth statuary and cart it off to private collections. Today, much of the Diocletian bathing complex lies in ruin or has disappeared entirely. Some pieces have been preserved, however, albeit in adapted form. Michelangelo transformed the frigidarium into Santa Maria degli Angeli, for example. What remains of the baths, beyond the church, today houses a museum.

Santa Maria degli Angeli has changed greatly since Michelangelo designed it, but it does retain the look of a Roman ruin, which was

his intention.