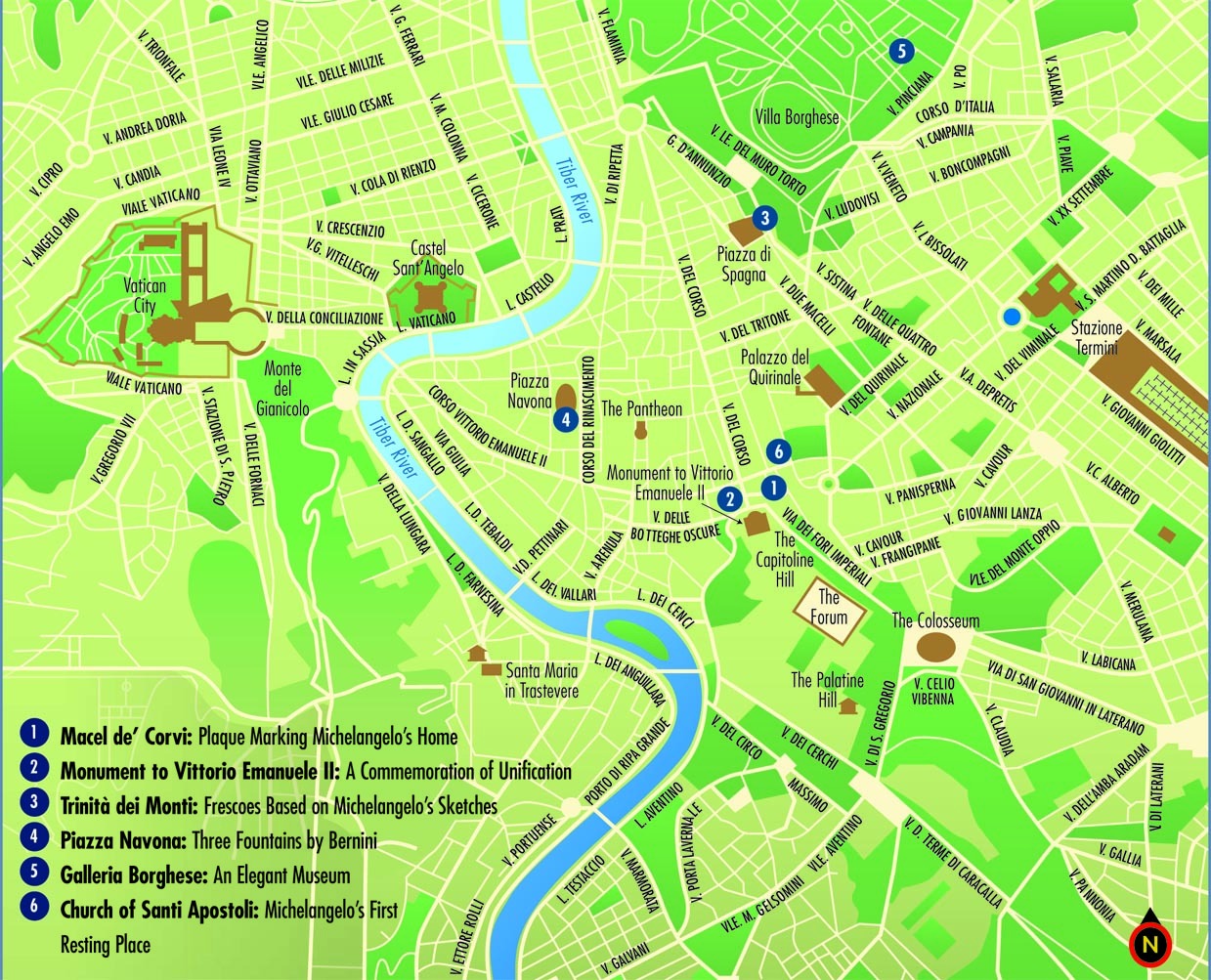

Chapter 9

At the Twenty-Fourth Hour

Michelangelo’s influence is

evident in this statue of Neptune

in the Piazza Navona by Bernini,

whom many critics consider to be

Michelangelo’s stylistic heir.

Michelangelo’s relationship with Rome, like so many of his other relationships, was complicated and layered. The city provided him with a living, fame, and fortune. In return, he helped to beautify it, bringing back to life an ancient treasure while infusing it with a new elegance and energy. For his contributions, Romans cherished Michelangelo—an appreciation that was enhanced by the myths that grew up around him even while he was still alive.

Ever the politician, Michelangelo helped to craft the stories his first biographers told about him. Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi wove tales of a solitary genius, self-reliant and independent. This image was true only to a degree, but it tallied with the humanist ideal to which the artist held himself. Michelangelo did not want to be seen as a humble laborer. He cultivated the image of a gracious artist with connections to the Medici and the popes, and in Vasari and Condivi he found willing accomplices. Yet, though the two writers held Michelangelo in great esteem, they did not shy away from portraying him as decidedly human.

Vasari published his biography in 1550. It included the life story not just of Michelangelo but of many other noted artists of his age. Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects more or less invented the genre of art history. With a focus on the artists of Florence, Lives shaped perceptions of good and great art for centuries, and Vasari held Michelangelo up as the supreme artist in his pantheon.

Michelangelo was not entirely pleased with Vasari’s Lives, however. Vasari relied on others to recount Michelangelo’s life rather than conversing directly with Michelangelo, and his first edition presented false or flimsy accounts of important events in Michelangelo’s life. For example, Vasari summarized Michelangelo’s forty-year struggle with Julius II’s tomb in one sentence. Michelangelo was offended and sent him a sonnet in response:

Although the poem appears to be complimentary, it is actually a cutting critique. Michelangelo, who thought Vasari lacked artistic talent, points out that Vasari is a better writer than painter. Moreover, as a humanist, Michelangelo believed that no one could replicate the natural world accurately. So the fame that he seems to write about at the end is actually infamy: Vasari would live on in shame. But Michelangelo’s harshest criticism of Vasari came in another form: he commissioned a biography by Ascanio Condivi.

Condivi’s The Life of Michelangelo appeared in 1553. Whereas Vasari’s volume is impersonal and inaccurate, Condivi’s is warm and authoritative. Condivi had the confidence of Michelangelo and spent much time interviewing him. As a consequence, Condivi’s account is more reliable than Vasari’s—which explains why, when Vasari revised Lives, he did so with a copy of Condivi’s book in hand.

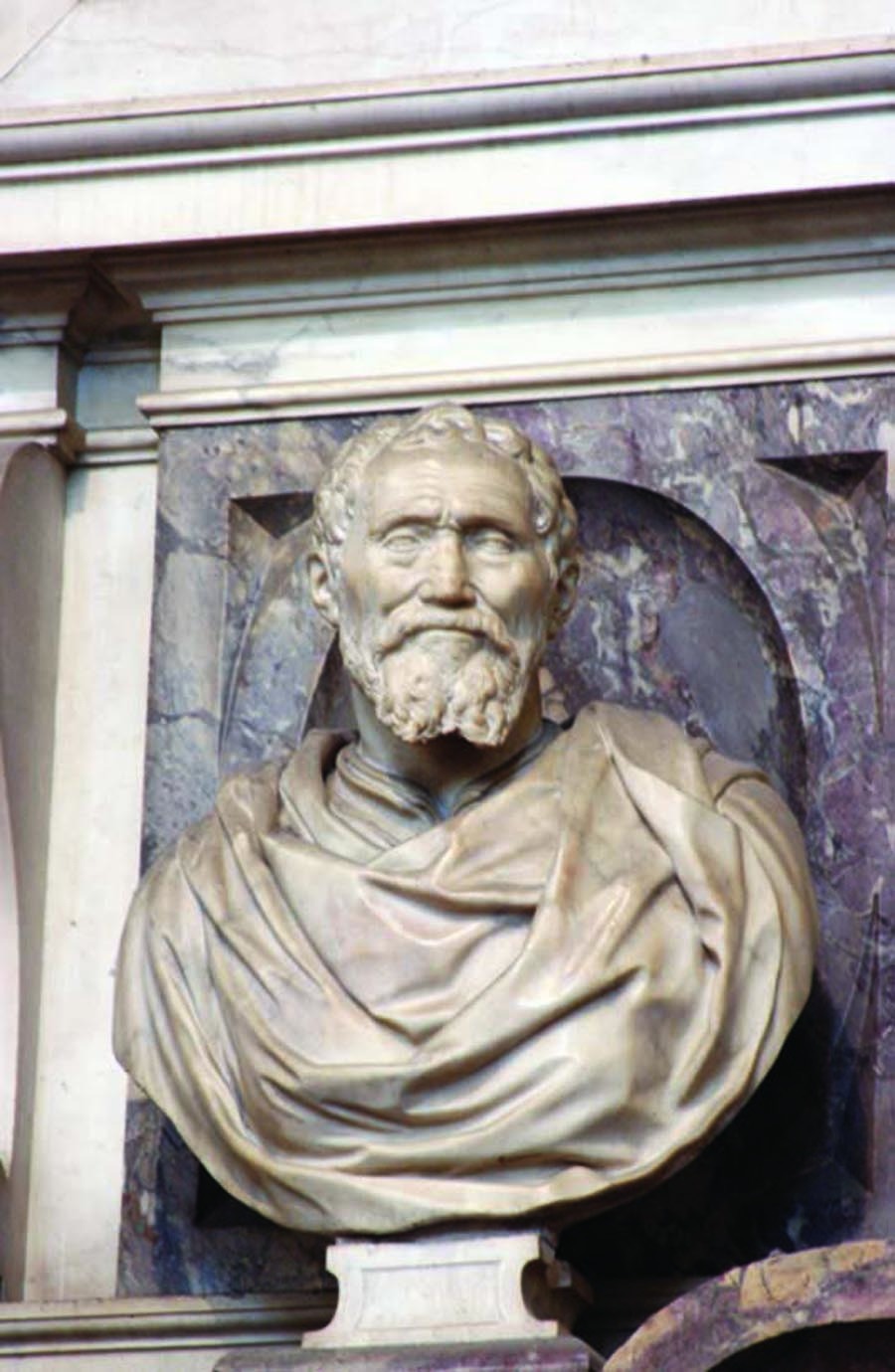

This bust of Michelangelo by Vasari is part of Michelangelo’s tomb in

Florence.

Curiously, Condivi disappeared from Michelangelo’s circle of friends after the publication of his work, whereas Michelangelo and Vasari maintained a relationship until Michelangelo’s death. Despite the criticism Michelangelo levied against him, Vasari was eager to please Michelangelo, revising Lives to portray Michelangelo’s life in a more realistic light.

Family and Friends

Despite his advancing years, Michelangelo maintained close ties with his family in Florence, especially his favorite brother, Buonarroto. The artist often wrote Buonarroto with complaints about his life in Rome. Buonarroto once replied: “You must value your person more than a column, the whole quarry, the pope, and all the world ... come home by all means and let everything else go to hell.” When Buonarroto died in 1528, he left a daughter, Francesca, and a son, Lionardo, who became Michelangelo’s only heir.

The Grieving Son

Upon the death of his father, Michelangelo penned a series of poems bemoaning his loss. Among them was this:

Lionardo sent Michelangelo gifts of sausages and linen shirts, beans, cloth, and wine. In return, from his comfortable home in the unfashionable neighborhood of Macel de’ Corvi, Michelangelo sent Lionardo and his other surviving relatives a stream of letters, not a few of which complained of their lack of respect for him and his work, their financial indiscretions, and their demands for help of one kind or another. Yet, though he might chide and admonish, he clearly treasured his family and supported his father, his brothers, and his nephew financially throughout his life.

Michelangelo felt the loss of his father keenly. Lodovico died in 1531, while Michelangelo was still living in Florence. Although father and son had fought over money and family, there was no doubting the depth of their mutual affection. The father’s death inspired the son to compose a series of poems.

Although he longed for Florence, Michelangelo found his best friendships in Rome. But his friends, like his family, were not getting any younger. In the fall of 1546, Luigi del Riccio, who had nursed Michelangelo through a severe illness, died. The next year, a month after Michelangelo was named architect of St. Peter’s, Vittoria Colonna died. Beset by a deep, penetrating grief, Michelangelo again turned to writing poetry, reflecting on Colonna’s life as a blessing in his own:

Not surprisingly, with his friends dying and his own health precarious, Michelangelo turned to thoughts of his mortality. Years earlier, people had marveled that Michelangelo could still work with remarkable vigor and accuracy. As a contemporary reported:

By the time of Colonna’s death, the sculptor, seventy-two, felt his age. “I am an old man,” he wrote that year, “and death has robbed me of the dreams of my youth.” Immersed in thoughts of mortality, he began work on what would become known as the Florentine Pietà, a piece that he intended to be placed on his own tomb. The project, eventually abandoned by Michelangelo, depicts Nicodemus, Mary, and Mary Magdalene supporting the dead body of Jesus. Nicodemus’s face is a self-portrait.

The Florentine Pietà never made it

on to Michelangelo’s tomb; it is now

housed in the Museo dell’Opera del

Duomo in Florence.

Michelangelo worked on the Florentine Pietà in solitude. One night Pope Julius III sent Vasari to the artist’s home, where he found Michelangelo at work on the Pietà by candlelight. When Vasari came into the room, Michelangelo “let the lantern drop from his hand leaving them in the dark.” “I am so old,” the artist said, “that death often tugs me by the cape to go along with him, and one day, just like this lantern, my body will fall and the light of life will be extinguished.”

In 1548, Michelangelo’s brother Giovansimone died. But probably a greater blow was inflicted in 1555, when Pietro Urbino, Michelangelo’s servant and assistant for more than twenty-five years, became gravely ill. The two men had developed a familial relationship over the years, and Michelangelo nursed his friend to the end. Urbino left behind a widow and two sons. Michelangelo was godfather to one of the boys, and he took responsibility for the entire family when Urbino died. He provided for them, invested money for them, and continued to look after them even after Cornelia, Urbino’s wife, remarried.

A Sonnet from 1554

After Urbino’s death, Michelangelo wrote to his nephew of his “intense grief, leaving me so stricken and troubled that it would have been easier to have died with him.” That grief, powerful and personal, may have inspired Michelangelo to begin his last sculpture, the Rondanini Pietà, which is in the Castello Slovzesco in Milan. Like the Florentine Pietà, this too is unfinished, yet beautiful and intimate. Unlike the Rome Pietà, which portrays Mary grieving over the body of her son in repose, the Rondanini Pietà is a composition of tension and balance. Mary stands on a rock struggling to hold the limp body of Jesus. There is tension in her precariousness, yet, like the Rome Pietà, the mother struggles to keep the body of her beloved son from the floor. Michelangelo, who lost his mother when he was six, returned again and again to sculpt and paint mothers holding and loving their children.

The elderly sculptor had the means to return to Florence at any time, but Rome kept him captive to the end. Yet, he was a willing captive. Michelangelo suffered from kidney stones and colic in his old age—both of which gave him an excuse to stay in Rome, where he could supervise the construction of St. Peter’s.

In 1555, he wrote: “I am at the twenty-fourth hour, and not a thought arises in me that doesn’t have death carved in it.” Yet he would live nine more years, until the age of eighty-nine—extraordinary in a society where fifty was considered elderly. In 1560, Vasari reported to Duke Cosimo de’ Medici, the ruler of Florence, “He now goes about very little, and has become so old that he gets little rest, and has declined so much that I believe he will only be with us for a short while, if he is not kept alive by God’s goodness for the sake of the works at St. Peter’s which certainly need him.”

Michelangelo lived in his home at 1 Macel de’ Corvi until the end, surrounded by friends and occasionally visited by his nephew, who stood to inherit a sizable fortune from his childless uncle. The artist, who continued working, retained one or two assistants, a male secretary, a cook, and a housemaid. They all lived in his home and provided company as well as their services. Pope Pius IV and Duke Cosimo visited him regularly, and their minions watched over him as well. Pierluigi Gaeta, Michelangelo’s friend and aide, brought regular reports from St. Peter’s.

Rome’s Wedding Cake

Macel de’ Corvi, the “Slaughterhouse of the Crows,” was in Michelangelo’s time an undistinguished neighborhood filled with homes, shops, and churches. The landscape changed in the late nineteenth century, however, when work began on an enormous civic project, the 2 Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II.

The monument, which was completed in 1911, emulates the architecture of the Renaissance and honors Vittorio Emanuele II, who ruled a unified kingdom of Italy from 1861 to 1868. His reign was far less pristine and harmonious than the monument, but the building expresses many of the ideals of humanism, honoring Italian history with a commemoration of civic service and a nod to ancient Roman design. In World War II, American soldiers in Rome nicknamed the it 2 “the wedding cake,” and the name stuck.

Today the Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II is the dominant feature

in what was Michelangelo’s neighborhood, Macel de’ Corvi.

Despite the danger that his celebrity and frailty might make him an easy target for thieves and fraudsters, Michelangelo was fully confident that those helping him were competent and trustworthy. In August 1563, he wrote to Lionardo, reassuring his anxious heir that no one was taking advantage of him.

Farewell

By January 1564, Michelangelo was dictating his letters because “my hand no longer serves me.” Yet he was still sculpting. He willed his soul to God, his body to the earth, and his possessions to his relatives in a last testament of just three sentences. On February 12, while working on the Rondanini Pietà, he became feverish. He spent hours burning piles of sketches and drawings. Even in his final days, Michelangelo was conscious of his reputation and did not want to leave behind anything he did not deem perfect or worthy.

Daniele da Volterra

One of Michelangelo’s students and a loyal friend, Daniele da Volterra executed many of his paintings based on sketches by Michelangelo. 3 Trinità dei Monti, the church at the top of the Spanish Steps and just steps away from the Villa Medici, holds two of Volterra’s works, Deposition and The Assumption, both of which show the influence of Michelangelo’s teaching. The Assumption includes a portrait of Michelangelo.

Bernini’s father designed the

fountain at the foot of the

Spanish Steps, which are so

called because the Spanish

embassy is on the piazza.

On February 15, he sent for Lionardo. His friends gathered. Daniele da Volterra and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri were among the loyal attendants who read to Michelangelo and retold, at his request, the story of Christ’s crucifixion over and over again. Michelangelo lay by the fire, and eventually moved to his bed. He turned to Volterra at one point and pleaded, “O Daniele, I am done for; I am in your keeping. Do not abandon me.” Not only did Volterra stay by Michelangelo’s side to the end, but he assumed his friend’s mantle after his passing, taking on the responsibility of painting clothes and drapes on many of the nudes in The Last Judgment.

Bernini: Michelangelo’s Heir

Born after Michelangelo’s death, sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) is widely considered the finest Roman artist of the seventeenth century. He designed the Piazza San Pietro and the baldacchino in St. Peter’s, and his gifts as a sculptor rivaled those of Michelangelo.

The son of an artist, Bernini grew up in an environment that celebrated sculpture. Bernini went on to design the enormous fountains in the 4 Piazza Navona. Once an ancient racetrack, the piazza holds three fountains that testify to the Roman reverence for water. Bernini’s figures also pay homage to Michelangelo’s—twisting, powerful, and muscular.

The Villa Borghese, once a private estate, now has several fine museums located in a vast park area. The 5 Galleria Borghese holds several of Bernini’s finest sculptures. David, a self-portrait, takes yet another look at the ideas of strength, valor, and honor that Michelangelo explored in his own David. With the Rape of Persephone and Apollo and Daphne, Bernini executes two tales from mythology with the same kind of reverence and passion and the same ability to capture in stone a sense of movement and moment that Michelangelo captures in Moses. Just as Moses is about to rise, so Daphne is in the midst of transformation and Persephone is captured in the moment of terrified realization. The museum also features the collection of one of Rome’s great art aficionados, Scipione Caffarelli Borghese (1576–1633). The favorite nephew of Pope Paul V, Borghese collected fine examples of ancient art as well as works by contemporary geniuses, including Bernini, Caravaggio, and Rubens.

The Galleria Borghese.

On February 18, 1564, Michelangelo’s doctor wrote to Duke Cosimo in Florence, saying, “This afternoon that most excellent and true miracle of nature, Messer Michelangelo Buonarroti passed from this to a better life.”

The church of Santi Apostoli, where

Michelangelo’s body lay in state, is

part of the Palazzo Colonna complex in

Rome, just blocks from Michelangelo’s

home in Macel de’ Corvi.

“Father and Master of Everyone”

Rome grieved deeply when Michelangelo died. His body was moved to the 6 church of Santi Apostoli, adjacent to Palazzo Colonna and a few blocks from his home. The very public funeral was “attended by the entire artistic profession, as well as all his friends.” Vasari recounts that “Michelangelo was buried in a tomb in the church of the Santi Apostoli in the presence of all of Rome, while His Holiness planned to erect a special memorial and a tomb in Saint Peter’s itself.” Michelangelo had expressed his desire to be buried in Florence, however, not in Rome. His friends knew, though, that the Romans would not let him go easily. So, unlike the public fanfare accompanying his interment in the church of Santi Apostoli, his body was moved to Florence two weeks later in secrecy, “shipped like merchandise in a bale ... so that in Rome there would be no chance of creating an uproar.” Florence welcomed her native son, and again Michelangelo’s life was celebrated in elaborate style, this time in the church of Santa Croce. The Florentine Fine Arts Academicians posthumously elected Michelangelo “prime academic”—“head, father and master of everyone.”

Giorgio Vasari, who played such a role in immortalizing Michelangelo on paper, designed his tomb and prepared the decorations for his memorial service. Romans may have felt betrayed. The promised memorial and tomb for Michelangelo at St. Peter’s was never built, but a small memorial was installed in the courtyard of the monastery next door to Santi Apostoli.

In the days that followed Michelangelo’s death, an inventory was taken of his home. His friends and relatives understood the value of his works, and they wanted to make sure nothing disappeared. The inventory records that Michelangelo was at work on three large marbles: one of St. Peter, one of Christ with a cross, and the Rondanini Pietà. It also reveals some intimate details of Michelangelo’s home life. In the room where he slept were a straw bed, a canopy of white cloth, “a long fur coat of wolf skin, old; a rough woolen lion-colored blanket, heavily used; another fur coat, half length, of wolf, with a cover of black cloth; a mantle of fine black Florentine material, with sections of black lining inside, almost new ... a rose undershirt with a rose silk border, heavily used ... a pale-colored undershirt with a border of the same material, heavily used.”

Giorgio Vasari designed

Michelangelo’s tomb in

Florence’s Santa Croce.

The inventory makes no mention of any books, paintings, sculptures, or drawings that were not religious in nature. Perhaps the influence of Savonarola lingered on, and Michelangelo’s burning of papers before his death amounted to his own bonfire of the vanities. The sculptor did not burn everything, however. Of the correspondence that survived, 480 letters in Michelangelo’s own hand provide a testament to his life and his friendships. Hundreds more from friends, relatives, popes, and kings bear witness to his influence and personal connections across social and political strata as well as geographical boundaries. Additionally, contracts, legal statements, poems, and notebooks, together with the testimony of his friends and biographers, create a portrait of an artist who was well loved and profoundly respected. Although he was cautious during his life about committing his political allegiances to paper, his surviving correspondence attests to his tremendous loyalty to the people whom he cherished—and venom for those he did not respect.

For his family, Michelangelo invested well. He had lived a simple but comfortable life and left enough to allow his family to do the same. Lionardo was his sole heir, and Lionardo’s descendents kept the Buonarroti family line alive until the nineteenth century. In 1858, Cosimo Buonarroti, one of the last of the line, donated Michelangelo’s Florence house (one that he owned but never occupied) and its contents to the city of Florence. Casa Buonarroti is now a museum and archive open to the public.

Michelangelo’s greatest legacy, however, is in the marble and plaster he transformed. This bequest of beauty and grace has shaped not only the appearance of Rome but also the experience of Rome for the countless millions who have lived in and visited the city since that “true miracle of nature” departed from it.

After Michelangelo’s body was

removed from Santi Apostoli in

Rome, a small memorial was

erected. It has subsequently

been enclosed in the courtyard

of the church’s monastery next

door, but a polite inquiry about

Michelangelo will generally gain

admission.