Your lips and your breasts are a honeycomb of anguish

And your mature belly is a cluster of grapes hung

from the colossal arbor of death… Like a yellow dog,

autumns follow you and, wrapped in fluvial and astronomic

gods, you are eternity in a drop of horror.

Pablo de Rokha, Cosmogony

Like all Chileans, Crabby spoke in a singsong way, her voice vibrating in her nose. She laughed at everything, even celebrity deaths, and made cruel jokes. She drank red wine until she collapsed in snores, only to wake up barefoot because someone had stolen her shoes. She ate empanadas and sea urchin tongues in green sauce seasoned with fresh, extra-hot chili. Whenever the cops beat a “political agitator” to death, she turned a blind eye, pretending not to notice. Actually, she wasn’t Chilean but Lithuanian.

She landed in Valparaíso when she was two, pulled along by her mother, a fat redhead who spoke only Yiddish, and her father a tall (almost seven-foot), skinny fellow as light on his feet as a bird. His profession was the most pedestrian imaginable: callus remover. Using prayer, he made the calluses on people’s feet fall off. Since his name was Abraham and his wife’s name was Sarah, he dreamed—for too many years—of having a son he could name Isaac, which in Hebrew means “he laughs.” After anguished efforts, ten months of gestation, anemia, forceps, a cesarean, a strangling umbilical chord, Sarah finally gave birth to a daughter. Abraham stubbornly insisted on naming her Isaac, but very early in life, even before she began to walk, the girl would burst into an angry fit of wailing the instant she heard that persistent “Isaac.” Only a teaspoon of honey would calm her down.

Intelligent, she could read by the age of four. She rejected the Ladino translation of the Torah, so her first book was Paul Féval’s The Hunchback. She so adored the character Henri de Lagardère that she began to walk hunched over, her legs spread, the tips of her shoes pointing in opposite directions, and her arms bent at right angles. No one bothered to correct her posture. The only thing they did manage to do was nickname her “Crabby.” She tossed out “Isaac,” which would have destined her to suffering the world’s laughter, and instead identified with her nickname, accepting the idea of being an aggressive crab separated from others by a hard shell.

By the time she was eleven, she’d broken a dozen classmates’ noses, so no school would accept her. Between his murderous chanting away of calluses and his davening in the synagogue, Abraham had no time to worry over his daughter’s education. Crabby’s school was the street. She learned a series of professions, among others: re-selling cheap watches for three times their original price under the pretext that they were stolen, painting the hooves of the horses used by funeral parlors black, washing and combing the dogs of high-class prostitutes, and manufacturing “smuggled whiskey” out of tea, crude sugar, and drugstore alcohol. When she was thirteen, she lost her father and menstruated for the first time. She mounted his unvarnished wood coffin as if it were a horse and rode along, staining it red. Sarah, seconded by her instantaneous new husband, kicked her out of the house.

Crabby, her face transformed into a bitter mask, set out on a tour of Chile, a country as long, thin, and foreign as her father. She ended up in the north, in Iquique, a bone-dry port, where the workers in the nitrate and copper mines would come down from the mountains to spend their weekly salary without noticing the rotten dog stench that poured out of the fishmeal plants and infected the streets. Crabby began to work as a maid in the Spanish Club, an “Arabian-style” building designed by an architect whose only knowledge of Islam came from the illustrations in the expurgated nineteenth-century French translation of The Thousand and One Nights. Since her hunchback gait upset the members’ stomachs, the management dispatched her to the lavatories. After a year, she began to sprout a beard. Unwilling to obey the requests of the Aragonese manager, she refused to shave. When the requests were accompanied by grimaces of disgust and insults, Crabby presented her resignation in the form of a punch that sent the brash Aragonese rolling down the stairs. She also beat up two waiters who had the misguided idea of avenging the manager, who lay on the Churrigueresque tile floor howling in pain from some broken ribs. While working in the lavatory, she had made and saved money selling the honorable members cocaine cut with talcum powder. She used her capital to set up a shop for buying and selling gold. She also became the local dentist. After the drunken miners had spent all they’d earned in six months on a weekend orgy, they would line up outside her little shop insisting on selling her the gold crowns that adorned their teeth so that they could go on drinking.

Two years went by, two years of drought. Then, suddenly, the mountains awakened wearing clouds for hats. The sky turned black, thunder roared, lightning flashed, and a deluge commenced with raindrops the size of pigeon eggs. The tempest went on for three days without stopping. No one could go out because the drops were so forceful they punched holes in umbrellas. Locked away in her shop, in the semidarkness, with no more beer to drink, Crabby suddenly, and for the first time in her life, realized she was alone.

The skeleton of her solitude appeared before her: impersonal, heavy, and cold. And then she saw flesh gather around those bones, forming a body for which she felt not the slightest tenderness. It reacted to her disdain by tightening itself around her from her stomach to her throat to deliver her a dull, constant pain. It was like having her soul pierced by a nail, in the depths of a world transformed into jelly, where she was sentenced to drown for all eternity. “Who am I? Can someone tell me? How could they, since no one has ever seen me? It hurts, it hurts! I am a wound awaiting the gaze of another in order to heal. A frog who will never turn into a princess. A freak, who when she wants to give, only gives the gift of disgust. The world’s indifference is my punishment!” She clung to the wall, sliding left and right, absorbing the darkness of the place through every pore until she felt she was black, a shadow that wanted to cry like a dog in the absence of a body to master it.

The drops exploded noisily on the tin roof. Nevertheless, a scream, so high-pitched that it became a long needle, pierced the rain’s atrocious drumming. Only a completely feminine throat could howl like that. Crabby, not knowing why, felt herself the mother of that female under threat of death and, waving the iron bar she used to frighten off hostile drunks, ran out onto the street.

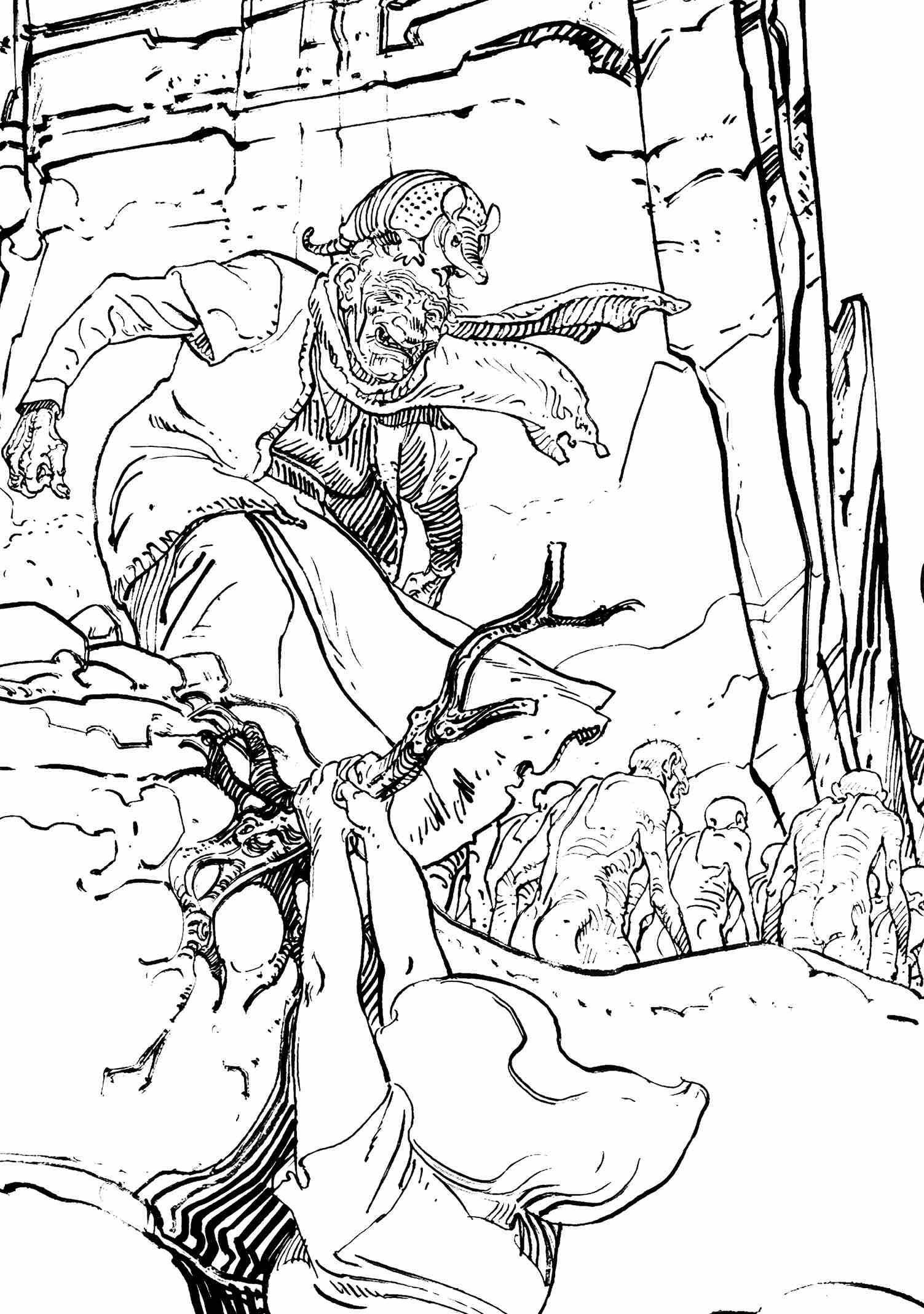

A mantle of gray mist hid the sky, forming thick folds. In the distance, a pale phantom began to take shape. It came toward her, running, a woman with extremely white skin, as white as flour, salt, marble, a shroud, or milk. It passed through the wall of water and fell into Crabby’s arms, shaking like a wounded albatross. It was as tall as her father, with powerful legs and buttocks and enormous breasts; she was very young, but her mad blinking revealed, beneath white eyelids, the pink irises of an old woman. The howling wind tangled her long white hair, baring a shoulder that had received a deep bite. Sniffing excitedly, foaming at the mouth, growling, three Asiatic monks wearing saffron robes ran toward them. The white woman hid behind Crabby’s back, using her as a shield.

Crabby whirled the iron bar. “Hold it right there, you fucking Chinamen! One more step, and I’ll smash your skulls.” The monks stopped for an instant, never taking their eyes off the marmoreal flesh the skinny body of her defender could not hide. Then they revealed the hands they’d been hiding in their sleeves. Thirty long fingernails, as sharp as knives, whistled menacingly. Crabby, unable to stop the attack, smacked her bar on the street: “May the devil swallow them!” With a colossal roar, the earth obeyed. A crack opened, and the mad creatures fell howling into the abyss. The enormous maw, now satisfied, closed. The rain stopped, the sun came out, ready to reign for another couple of years, and to celebrate the return of light, thousands of small parrots, forming a multicolored cloud, chorusing syllables Crabby interpreted as “Albina, Albina, Albina…”

The enormous woman, expressing her gratitude in infantile sobs, gave no sign of leaving. There seemed to be no other place in the world for her but Crabby’s arms and bosom. Crabby led her into the shop, sat her down in the armchair, and, with a tenderness never before seen in her, began to clean out the bite.

Albina (that’s what Crabby named her, obeying the parrots’ message) had lost her memory. Quite often she’d utter sentences in a strange language that sounded like “Om badzra puspe ah hum svaha or Byhams dan sñin rje btan.” At the beginning, Crabby had to bathe her, feed her, teach her to walk and use the bathroom. She learned quickly, and by the end of six months, she could speak Spanish and take care of her needs properly. Nevertheless, there was still an innocent look in her pink eyes that suggested she was seeing everything, absolutely everything, for the first time.

Crabby asked around, but no one recalled having seen any Asian ships docked in the port. Was it possible one could have entered the port at the start of the deluge, while the workers took refuge, and left just when the rain was letting up? Who knows? Crabby was destined never to unravel the mystery. The only trace of the past on her protégée was a tattoo emblazoned at the beginning of the deep crevice separating her buttocks: an asp held in place on the letter T by three nails.

During work hours, Crabby dressed her pearly friend as a nurse. By waving two silver paper fans, she could waft a breeze onto the sweaty miners. Stunned, their eyes fixed on the mountains bulging from the linen uniform, they allowed not only their gold crowns to be pulled but also their teeth along with them. A woman as pale as Albina had never been seen before in those regions where the sun turned even the toughest skin into leather in a few hours. At the end of the afternoon, Crabby would emit her mandrill shrieks and wave her iron bar around to expel the drunken gluttons who wanted to go on in the ecstasy produced by Albina’s protuberances. She would close the shop, scatter lice powder, and sit down in her awful armchair making an embittered face but half-shutting her eyelids so that no one could see the joy that flooded her eyes.

Then Albina would take off her uniform and, naked, prepare tasty dishes: meat, greens cut into the shape of flowers, treats in which the spicy, sour, bitter, and salty all mixed together without excluding the sweet. After stuffing herself, Crabby would belch, say she was very sleepy, and unroll the mattress. Meanwhile, the huge woman would go off to the tiny bathroom to pour out a long and thick stream that was probably as white as she was. “She pees milk, I’m sure!” Crabby would stretch out on her back, completely dressed to hide her ugliness, and with her arms spread would pretend to sleep. Albina, walking on tiptoe, would then stretch out next to her. Resting her head on Crabby’s almost flat chest, she would fall asleep instantly. Crabby would open her eyes and for hours listen to Albina’s snores, which were like long notes blasting from a trombone. When sleep finally overcame Crabby, she would open her mouth wide and give out hoarse wheezes that made the floor, walls, and roof shake. Albina would awaken, go down to the beach, and swim among the phosphorescent waves like a glowworm, then return to the dumpy shop, prepare breakfast, and awaken Crabby by kissing her feet. Crabby, red with pleasure, would open her eyes and shout, in feigned disgust, “Shit, another day!”

Months went by with the charm of a babbling brook. Crabby, lacking a God she could thank for her huge gift, hung a stuffed parrot over the lintel and placed seven candles at its claws. “Holy old bird, if everything that begins ends, make the end come as slowly as possible!” It may be that Crabby either chose the wrong God or that the parrot was deaf, but either way, almost immediately four policemen appeared proudly waving an arrest order. “Citizen, the director of the Spanish Club accuses you of armed aggression and of trafficking in cocaine. You must come with us, either peacefully or by force!”

“Three years have gone by since he fell down the stairs and broke his ribs! That Aragonese faggot wants to get his revenge at a distance. Albina, what will become of you? You can’t pull teeth. And my detainment may be long; with these cops, justice turns into a tortoise.”

“Don’t worry, Crabby,” said Albina. “I may not know how to use the pliers, but I do know how to use the scissors.” Then she asked the suffering miners, “Who’d like me to cut his hair?” Every one of them spit out the cotton swelling their cheeks to shout “Me!” in one voice.

Crabby’s detention lasted forty days. But, since no member of the Spanish Club would diminish his own glory by testifying—that is, admitting he’d used cocaine—and since the bones of the man from Aragón had healed long ago, they released Crabby, much to the relief of the police, who couldn’t stand seeing that fierce spider squatting, huffing, and puffing in the corner of her cell. Now it was Crabby’s turn to rub her eyes. Was this her gold exchange shop? The once somber facade was now painted a violent purple. The splintered wooden screen had been replaced by a curtain with metallic fringes, and a red lamp blinked in the window. A bolero rang out from a gramophone playing at full volume. Crabby, half-closing her eyes as if she were about to see a corpse, pushed the curtain aside. The place was packed with silent, unmoving men in a trance staring at a corner of the room. There, standing on top of a wooden barrel, was Albina, wearing only a G-string, exhibiting her enormous breasts, and shaking her hips to the rhythm of the song. From time to time, a miner would stand up and, moving like a sleepwalker, place a banknote in her elastic waistband. The only light in the room came from the parrot’s seven candles; Albina’s whiteness devoured the darkness.

Crabby prepared to let out some mandrill shrieks that would frighten even the lice out of the place, but one glance from Albina, whose pink pupils were shining intensely, stopped her dead. The giant stepped down from the barrel and walked through the crowd, which parted at her approach as if her white flesh were red-hot iron. When she reached Crabby, she fell to her knees and kissed her toenails. “The boss is back!” Everyone applauded. Crabby tried to smile and twisted her mouth into a bizarre grimace. “Friends, the show is over!” she said. “It will begin again the day after tomorrow, when we’ve organized things a bit better!” Without moving, the miners turned their questioning eyes toward Albina, who said, “Yes, move along now!” And they all obeyed without raising even the slightest disturbance.

The two women calculated that in their thirteen-by-twenty-foot space, more than a hundred men could fit if well packed in and standing. They would only be admitted if they agreed to move only their arms to drink glasses of the reddish mistela Crabby knew how to prepare so well. To make the drink, she would boil water with cinnamon and sugar until it was the color of bark, then toss in some grain alcohol. They also decided to sell skewers with pieces of roast meat, udders, hearts, kidney, snout, ears, and sausage. Crabby proudly painted a sign reading CLUB IDEAL and nailed it to the purple facade. They replaced the barrel with a triangular platform that fit into the corner better. To top off the new arrangement, they covered the G-string with silver spangles.

Their clients, crude miners with inexpressive eyes and stony faces, filled the place and stood stock-still, hypnotized by the white goddess. Crabby’s mistela was strong, and after a dozen glasses their knees gave out. They fell prostrate, sometimes foaming at the mouth, propped up by the legs of those who could still stand. Late at night, Crabby stopped distributing drinks and skewers, turned off the gramophone, and covered Albina with a black mantle as if she were a plaster saint. The miners left the establishment walking backward, bowing, and making the sign of the cross. The two partners, after fumigating the place, counted their money and hid it behind the parrot.

The days began to slip along with the delicacy of fine silk. The men really worshipped Albina. Not a one of them, no matter how drunk, ever showed any disrespect for their living Virgin. Understanding the deep ecstasy of the workers, whose sexual desire transformed into mystical adoration, Crabby began to serve them dressed as a priest. The two women worked from eight at night until six in the morning. They got up late, and then went out to stroll along the beach for hours so Albina could pick up agate stones. Sometimes, looking for red pebbles, they would wander among the rocks that took the place of forests on the arid hills. Crabby’s joy was immense, because even though she found nothing of interest in nature, she did see one thing in life: its incessant death. Albina, for whom any detail was a miracle, saw, through her clean gaze, a revelation of the world. Thanks to that innocent admiration, to that pleasure in living the instant as if it were the most beautiful of jewels, she felt for the first time the benevolence of the stars, admired the funereal beauty of toads, listened to the albacores proclaiming their love for the ocean in song, understood that the shadows of the flies formed letters in a sacred alphabet, and recognized that every stone gave off a different perfume. The fact is that Albina, with her little girl’s naiveté, saw the world backward as if she were hung upside-down. Listening to the chirping of a bird, she said, “In order of importance, first comes the song, then the bird. Because in reality the song was created so that the bird would exist and not the other way around.” Crabby, moved, answered her: “I’m going to give you a notebook where you will write down everything you think.” Then, using a twig to draw in the sand, she began to teach Albina to write.

In turn, Albina taught Crabby to kiss.

“Try to imagine I’m a man,” she said, making her voice hoarse.

“I can’t! You’re the least manly person I’ve ever known!”

“Make an effort, Crabby! Imagine I’m so strong that I can hold the whole world up in my arms, then let yourself fall, give in, stop giving, receive and receive and receive. Imagine that your mouth is death and that my mouth is life, and swallow without stopping.”

As Albina kissed her, Crabby locked herself away in her crab position, becoming a tense ball; she had goosebumps all over. She contracted even more until suddenly, with a cracking of bones, she completely relaxed, turning to water in Albina’s arms. Before kissing Crabby, Albina had drawn a beard and mustache on her face with mud. Crabby’s mind was dissolving. She was a piece of cork floating in a limitless ocean. When her friend released her, she collapsed onto the parched earth and remained there, stretched out staring at the cloudless sky, sensing it as not outside but inside her head. Then she felt ridiculous, returned to her crab position, and ran clumsily among the rocks. If she found a cactus, she would embrace it, knowing that no thorn could pierce her.

This happiness lasted until Drumfoot turned up. He was a city inspector specializing in taxes and fines. His nose ran constantly, and the sweat stain on the back of his khaki shirt took the shape of a cockroach. His left foot was twice as large as his right; it was a spongy mass that fit into no shoe, so he wore a sandal that contrasted strangely with the patent leather boot on his other foot. In his voice there was no room for sentiment, only pisco vapor: “Look here, my little friends, you’ve committed multiple infractions: you have no license, no sanitary facilities, no fire exit, you’ve violated the city’s moral code. You keep no books, have no fire insurance, pay no taxes, and do your business totally underground. I swear by my swollen foot that if you don’t make a deal with me, I’ll turn you in. The cops will close you down until we get the order to sink you forever!”

“And what’s the deal, Mister Inspector?” Crabby asked, her mouth bitter. If this degenerate informed the police they were lesbians, they would be put with the homosexuals that General Ibáñez ordered chained up, their feet weighed down, and tossed from a plane into the sea. Drumfoot smiled and put on the expression of a cynical child, stared at Albina’s breasts, and said, “I’ll come by every other day two hours before you open up so that Miss Whiteass here can deliver me her charms! I’m sure that after a while, she’ll thank me for my visits, because aside from my personal qualities, I’m blessed with a quantity in a certain area that makes it unnecessary to envy a donkey. Of course, the young lady will have to put some effort into these encounters because the visits will last until I tire of her. Then jail and ignominy will have a turn. My law may be sticky, but it is the law!”

“Look here, Mister Inspector, my friend is having her period. Today is Monday. If you come by on Friday, she will take care of you in the manner you deserve.” Drumfoot grinned, perking up his mustache tips, and jumped onto Albina, sticking his tongue into her mouth for a long time. Then he dried his lips on Crabby’s priestly soutane, made a half turn, and walked off humming a military song.

On Friday, Crabby received him, opening the door halfway. The mattress was unrolled in the center of the room. The gramophone played softly, and, on the triangular platform, Albina, naked, followed the music’s rhythm by shaking her pubis, covered by a dense thicket of white hairs.

Drumfoot, his face contorted with desire, began to undress. Before he could take off his trousers, Crabby handed him a glass of her hot mistela. The man swallowed it in one gulp. “Fun and games are over, Missus Ugly, and get the hell out of here before I kick you out with my fat foot! And you, milky ass, come down here, open that mouth wide so you can take it all in, come swallow your master!”

As that, he began to unbutton his fly. Without even getting to the third button he fell deeply asleep. Crabby approached him and pricked his normal foot with a pin. No reaction, he went on snoring. Suddenly, Albina knelt down next to the sleeping man, bit his shoulder with a strange squeal, swallowed the piece of meat she’d pulled off, then began blinking, as if she’d just awakened from a long nap. Crabby instantly erased that incident from her memory. “The pharmacist didn’t lie; five of his sleeping pills can make an elephant fall asleep! Get dressed, Albina, while I finish undressing this guy.”

They took the money they hid behind the parrot, burned the inspector’s clothing, locked the door, and left on a bicycle built for two. They headed north, along the narrow coastal road.

“Albina, there must be a place that isn’t infected by the smell of rot, a place where the miraculous can flourish. A clean town with a soul that corresponds to you, with no Drumfeet around to sully you! We’ll travel until we find it!”

Crabby pedaled in the forward seat. Albina, behind, moving her enormous legs automatically without holding onto the handlebars, was writing in her notebook: “I don’t know where I’m going, but I do know with whom I’m going. I don’t know where I am, but I do know that I’m here. I don’t know what I am, but I do know how I feel. I don’t know what I’m worth, but I do know not to compare myself to anyone else. I don’t know how to dodge punches, but I do know how to withstand them. I don’t know how to win, but I do know how to escape. I don’t know what the world is, but I do know that it’s mine. I don’t know what I want, but I do know that what I want wants me.”

In that manner, they reached the outskirts of Iquique. The fishmeal factories appeared, covered by a thick layer of café-con-leche-colored dust and vomiting thick smoke that slithered up through the chimneys and down to the ground, where they threw down roots and stuck. Rotten meat, acrid excrement, fermented guts—the stench passed through their pores, infected their blood, and tried to infect their souls. Crabby made Albina sit up front and pedaled behind her, sinking her nose into Albina’s wide back. The pestilence was like the mass of demons born from Crabby’s intestines, and the fragrance that emanated from Albina’s white skin, the redemption of the world. Barely breathing, they covered twelve more miles.

After a steep hill, the ocean appeared, sending its salty aroma toward the flank of the mountain, which, under that extended caress, responded with a thousand perfumes from its ocher earth. “Let’s stop to enjoy the pure air and to eat a bit. Just look, Albina, all I have to do is stroll among the rocks on the shore for the crabs to come to me.” Which was exactly the case; hundreds of crustaceans came out of the cracks and began to follow Crabby. It was easy to catch a couple, open them up, roast them on a red-hot stone, and devour them. All the while crabs never stopped rubbing against the legs of the woman they considered their Universal Mother.

A ray of lunar light passed through the keyhole and hit Drumfoot’s forehead. He awakened without realizing he was naked, and lifted the leg with his normal foot to scratch himself behind the ear. Then he went into the kitchen and lapped up the water in the washbasin. Since the door resisted his shoves, he pulled up some of the floorboards and used his hands to dig into the clayish soil and make a hole to get out. He howled at the waning moon and set out, bent over, sniffing the road. “Mmm… they stopped here and placed their feet right on this spot… mmm!… they peed here and… mmm!” He rolled around in Albina’s excrement, panting with pleasure.

Some soldiers on coastal patrol found him that way, naked and carrying out that fetid act. After giving him a good thrashing, paying no attention to his heartrending barks, they dragged him off to the police station. After two days, he got his mind back. The bite on his shoulder had healed, leaving a violet, half-moon-shaped scar. “Those witches will get what they deserve!” Drumfoot spent hours sharpening his knife.

The narrow road built by the Incas along the ridge seemed to float over the abyss. Far below, the waves, transformed into gigantic foamy lips, called to them, insidiously sucking. Luckily, the landscape flattened out little by little, and the path was swallowed up by the dunes on a beach. Albina stripped, ran over the hot sand, and plunged into the glacial water. Crabby followed her, fully dressed. They swam, frolicked, ate clams, and drank the little water they had left, knowing that if they didn’t find a town soon, thirst would swell their tongues.

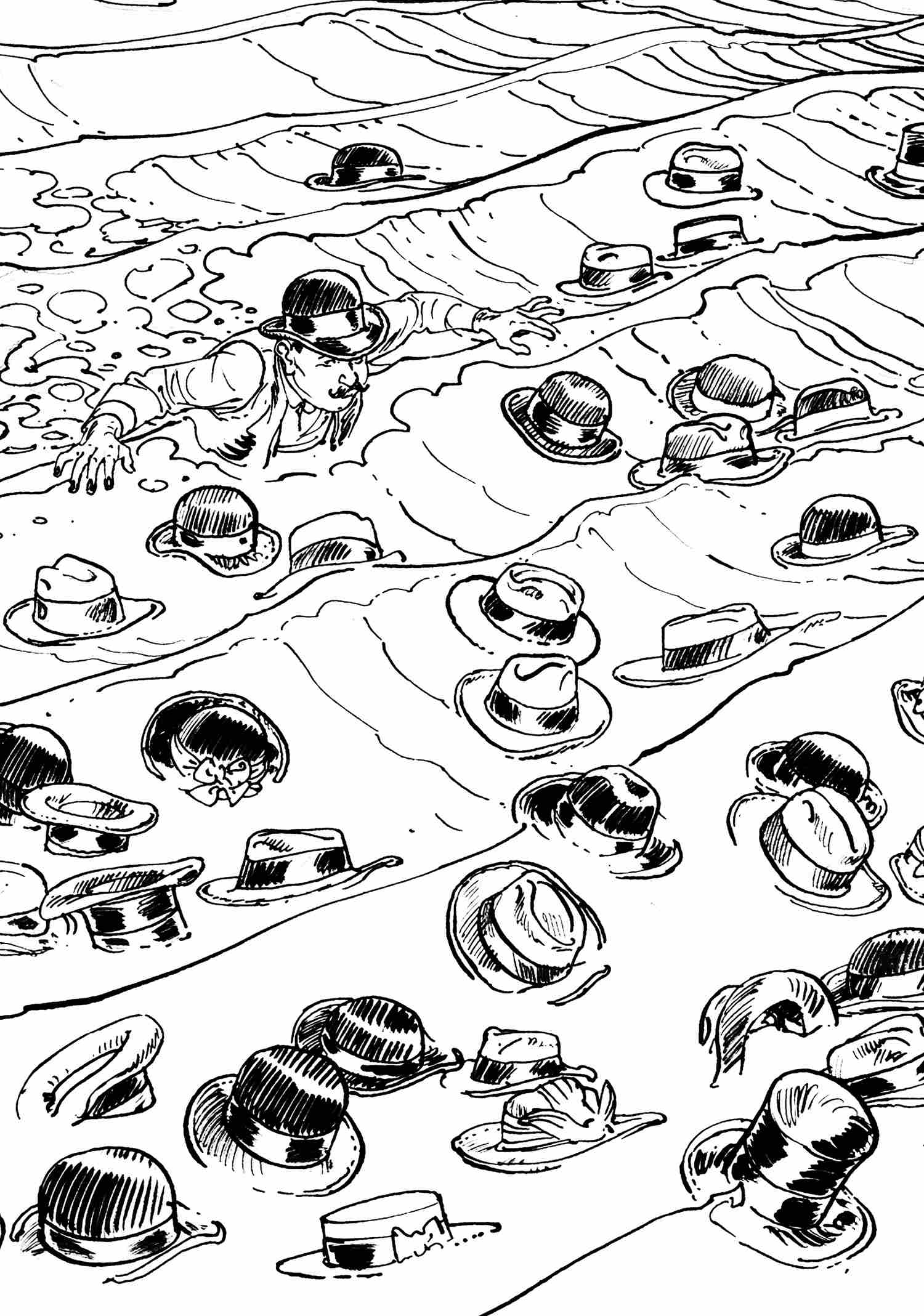

Twelve bowlers floated out of a creek followed by top hats, pith helmets, military caps, pork pie hats, Panama hats, and a huge variety of hats with upturned brims. The tide was carrying them to the shore like an armada of fragile little boats. The intrigued women climbed the rocky wall. On a narrow beach, a small man—he had no visible deformity, so he couldn’t be called a dwarf—surrounded by empty hatboxes was staring out to sea. As they watched he burst into high-pitched laughter, ran toward the high waves, and let himself be carried away, beginning to drown in those convulsing waters.

Albina dove in. Swimming vigorously, she reached the desperate man, knocked him cold with a punch to the jaw, and floated him to the beach. Crabby shouted in a rage, “Why did you bother to risk your life? You should have let him carry out his destiny! He may be small, but he is a man, and one less man in the world is a good thing!” The drowned man opened his eyes, and with an amiable smile said to Crabby, “Madam, perhaps my destiny was to be saved by your friend here, or, even better, perhaps I’m here so that your destiny can be carried out. The plans of mystery contain multiple paths. But I see you have eaten clams! Allow me to translate what these scattered shells mean.” And the little man examined the remains.

“The white lady, who has fled from a temple—I don’t know if she transmits a blessing or a curse. She’s something less or something more than human. With regard to you, Madam Anger, it seems you hate men because you see them as identical to your father, a thin, tall, dead man who was a callus remover by profession. Since I am the opposite of him, a pudgy, living, short man, a hatmaker by profession, you may accept me as a partner without a second thought.”

“As a partner? You’re raving mad!”

“Wait a second, let me go on interrogating my clams. A dangerous enemy is chasing you. One of you dances, and the other manages her. You’re looking for a tranquil place to set yourselves up. Now I appear. About a mile from here, in a ravine near the Camarones River—not much of a river, true, but more than welcome in these sandy territories—is my town, Camiña. A little-known place because the highway is far away from it and you can only get there on foot or by mule. About forty years ago, miners loaded with silver from the Chanabaya mine came to town. My father sold them all kinds of hats, because they wanted to look elegant for the prostitutes working in the saloons. But the silver veins gave out, the miners went off to other regions, and the whores followed them. I inherited an enormous shop filled with bowlers, wide-brimmed, narrow-brimmed, and pork-pie hats opening their felt jaws hungry for heads. Those mute complaints drove me to despair. With no other profession than this useless hat-making business and forced by my stature to have no wife, sick with boredom, I decided to bury myself in the sea along with my little felt brothers. But as you two may see, I have a different destiny. Come with me, I’ll give you everything I have, a magnificent shop in the center of town! There you can set up, as the clam shells tell me, the café-temple you want!”

Hiding a smile under her severe face, Crabby looked over at Albina, certain she’d burst into a crystalline laugh of approval. The little man was offering them exactly what they had been seeking but had no hope of ever finding, convinced they could only locate it in an unreachable future. But perhaps because the day ended so brusquely, devoured in one bite by the full moon, Albina tensed her muscles to the point that her white skin turned garnet red, showed her teeth, as if all of them were canines, and stuck out a hard, black tongue. Leaping like a wild beast, she snatched the hatmaker, wrapped him in a rib-smashing embrace, pulled off his clothes, rubbed her body with his as if the poor man were a sponge, and bit him on the left shoulder, pulling off a piece of flesh she swallowed with delight. Squealing with a sensual pleasure that filled her stomach with waves, she sat down, foaming at the mouth, and recited for hours incomprehensible words: “Bhavan abhavan iti yah prajanate… sa sarvabhavesu na jatu sañjate.…” Crabby, always wearing her severe mask, swallowing her astonishment (she considered that with regard to Albina’s unsoundable mysteries it was just better to let them pass, perhaps like divine serpents), picked up the hatmaker’s torn clothing, took needle and thread out of her pocket, and with the precision of a sailor sewed everything back together. The hatmaker, almost stiff, sometimes emitted small barks or wiggled his backside as if wagging an invisible tail. Soon the sun came up. No sooner did the first ray of light caress her face than Albina, even though she hadn’t slept, seemed to awaken from a deep sleep. Pale once again, she made a small cry of sympathy and went to the hatmaker, who was still in a faint, and licked his shoulder. The wound closed in a few seconds and became a violet half-moon.

While Albina recovered from her attack by breathing in the sea air and waving her arms like a giant albatross, Crabby dressed their new friend. When she put on his trousers, she surprised herself examining with pleasure that short, large-headed pink penis arising humbly from a clenched scrotum grooved with wrinkles ordered like an ancient labyrinth. It enraged her to admire that sublime and grotesque appendage. She smacked him on the back, and barely had he blinked when she said incisively, “Seeing is believing, John Doe. If your worship says we three are knotted into the same destiny, let’s not make a habit of rejection, and let’s accept that Camiña awaits us. But before we take the first step along that fatal path, please be so kind as to tell us your name—that is, if you have one. I for one don’t go beyond my nickname. Crabby, at your service. My friend, in accord with her pigmentation, is named Albina.”

“Madam Crabby, Miss Albina, for many years now I’ve been called Hat Maker. Even so, I must confess—overwhelmed by shame, since it is a ridiculous injustice—that I was baptized Amado, because my last name, perhaps of Italian origin, is Dellarosa. So I am ‘beloved by the woman who is a rose!’ How’s that for a lie?” And the little man began to weep. Crabby spit violently toward the parched hills so that she wouldn’t feel the knot in her throat.

In that dried-out valley, where the earth was a hard shell covered by a pattern of angular cracks, Amado Dellarosa guided them for hours along a steep path that went forward, backward, twisted left, then after a very long curve, went right, straightened out and again went forward, repeating the same movements again and again, hundreds of times. Crabby shook her head trying to banish an impertinent thought: this capricious path was a labyrinth that resembled in every detail the wrinkles on the little man’s scrotum. Albina, perhaps affected by rays of the sun drilling into her skull, began to repeat obsessively a single sentence: “Seek in the root the future flower.” Finally they entered a grand plateau surrounded by mountains: Camiña.

The town consisted of an extensive circle of wooden houses built around a plaza where grew four enormous cypresses whose trunks were studded with woody eyes, making them look like a nest of ghosts. No living person or animal was visible. No breeze shook the spiny branches, no curtain waved, no fly buzzed. Everything looked clean, dry, immobile, and silent.

“Dear friends, don’t think my town is a cemetery. After twelve o’clock noon it’s so hot that all inhabitants, along with their pets, retreat to the penumbra of home and take a seven-hour siesta. For their part, the wild animals dig tunnels under the desert plain so they can let the heat pass while in narrow but cool grottoes. Believe me, King Sol hits so hard in these parts that the mosquitoes die in midair. Later in the afternoon, when the temperature becomes agreeable, the businesses still functioning—barbershop, billiard hall, grocery store, herb shop—open their doors while the townspeople stroll the ring-street, men in one direction and women in the other, doing nothing else but staring at one another and saying hello. Nothing extraordinary ever happens here. When the Chanabaya mine closed down and the miners left, the Lady, along with her whores, went off after them. By some miracle, she forgot us. For a long time now, no one has died in Camiña. Old folks, when they’re informed they have to give up and yield their spot to someone new, go to live in the abandoned mine tunnels, a charnel house that goes on for miles toward the very entrails of the earth. We know they’re still alive because from time to time they form a chorus and sing old love songs. It seems—though no one has proven it, as we’re all scared to death of even going near the mine—that they eat the red clay that covers the walls. As for us, we’ve learned to survive by keeping bees from the pampa. It’s a rare species, peaceful up to a point. If you approach them on tiptoe, fine, but if someone approaches planting his entire foot on the ground, they sting him without pity and he falls into a coma, transformed into a mass of rashes. For lack of flowers, these worker bees suck the juice of sea algae and make a delicious, salty honey. As you can see, the roofs of all the houses are covered with hives. Pinco, the deaf-mute, transports our product to Arica on burros. The tourists just love it, and the money we get from sales allows us to survive. We are bored, yes, but in a certain way we secretly enjoy the fact that we have at our disposal an apparently infinite amount of time. You must understand that lacking any end changes your mentality. The urgency to do things disappears; idleness, once a sin, has become a virtue. The present moment stops causing trouble and offers us its unconcerned calm. Hope, because it’s unnecessary, is expelled from our souls along with fear. Since we all have the security of living, the only thing we long for is to sleep and find the opium that is pleasant dreams. Solitary pleasure is preferred rather than bothersome coitus. Seduction, lacking a mortal anguish to exacerbate it, becomes an obstacle. A long robe, wide and black, accompanied by a handkerchief worn on the head, makes all women identical. It makes no difference whether you marry this one or that one, and that’s only done when a pregnancy is needed to fill the vacancy left by an old person. Do you see why I tossed my hats into the sea and wanted to make the waves my grave? Living without death is not living. But here I am going on and on, while the hat shop awaits us.”

No one peered out to see them arrive, despite the fact that their footsteps, no matter how hard they worked to make them weightless, resounded on the whitish asphalt, turning it into a drum. Suddenly, a voluminous bee, its body a brilliant scarlet, flew over to trace a halo around Crabby’s head. The hatmaker whispered, “Make not the slightest gesture. It’s a warrior-spy. It can sting without losing its stinger, and its poison is deadly.” Crabby, stiff despite the heat, thought she would sweat ten thousand gallons of cold water. And her terror increased when the animal slowly flew toward Albina. Smiling, Albina shook her hips, opened her mouth, and stuck out her tongue. The bee landed on that moist appendage and began to drink her saliva. Gorged, it used its stinger to draw a tiny cross on Albina’s white throat and then drew another on Crabby’s forehead. Then it flew off like a flame to its hive. From all the roofs arose a general buzzing, rather like rain falling from the earth to the sky. “Well,” said the little man, “both of you were accepted! Hallelujah! I don’t have to tell you how many smugglers and bandits have been killed by those guardians! Without their permission, no outsider enters our town.”

Crabby swallowed her rage. Without warning her, this squirt had dared—a second time—to place the life of her friend at risk. Her own mattered nothing to her, but Albina’s? Shit! To say man is to say calamity! Nevertheless, the bitter saliva in her mouth became sweet syrup when the miserable pygmy raised the metal gate and, with the face of an angel, the eyes of a dove, and the gestures of a gift-giver, showed them the spacious place, where more than two hundred idiots could be packed in. “Thank you, Don Amado!” The now-likable little man stood before her on tiptoe and offered her his forehead. Crabby wrinkled her nose in disgust for an instant, and then, suddenly, as if a stretched elastic band had broken within her heart, she smiled for the first time at a man. Enveloped in a cloud of tenderness, she bent over, and planted a kiss between his eyebrows. Bursting into diaphanous laughter, Albina took off her clothes, and with her marmoreal skin shining like a star in the half-light, began to dance in order to bless the new café-temple.

On a khaki motorcycle, Drumfoot traced the road that rose toward the north. A blood infused with hatred accumulated in his erect penis. In his right fist vibrated a knife, also infused with hatred. The two extremes were guiding him; one wanted pleasure, the other death. While the mountain wind had swept away all tracks from that dirt path, a third extreme, his nose, with its abnormally developed sense of smell, picked up traces of the effluvia emanating from the white woman. It was a vaginal scent, unctuous, biting, bittersweet, greenish, as fragrant as the ivy flowers that open at dawn. Mmm! Suddenly an intolerable stench expelled him from his olfactory paradise. Blood poured from his nostrils. Barking his complaints, he passed by the fishmeal factories. He began to cough, lost control, and, making a leap, twisting like a beast, he fell on all fours, clinging to the edge of the pavement while his motorcycle smashed to pieces on the rocks a hundred yards below.

He left behind the sticky smoke infecting those territories and reached the beach. Vomiting, he ran to dive into the frigid ocean. When the salt water had extirpated even the tiniest particle of stench, he shook his body vigorously, surrounding it for a few seconds with a cloud of golden drops. He growled with satisfaction; there, abandoned at the outset of a narrow path, stood the bicycle built for two! He sniffed it over from end to end, from the handlebars to the tires. He licked the seat that had sunk itself between Albina’s buttocks, and then, overwhelmed by an enraptured hatred, his lower jaw tremulously revealing his canines, he ran along the path, his knees bent, using his hands as feet by leaning on his fists. Soon, so many curves, advances, twists, and switchbacks exasperated him. He located a point in the north, his goal, and left the path to get to it in a straight line. When it was already nightfall, after many hours of trotting, he realized with angry shock that he’d reached his starting point. There was the bicycle, now covered by a sheet of crabs.

It only took three or four hours for them to finish setting up their hall. All they had to do was empty it. They eliminated chairs, counters, hat blocks, irons, shapers, a fitter, pieces of felt, teatina straw, palm fibers, and sacks filled with hat liners. They stored all that in the basement and dragged up a barrel that had once held wine. This they placed in the center of the empty hall as a pedestal for Albina. As Crabby always said, “Less is more.” In that temple, any object, no matter how small, would dull the splendor of the white priestess. Amado grinned at her like a fool and agreed: “That is certainly the case, miss. A single, tiny cloud in the midday blue can darken the entire sky.” In the back room, they set up the electric cooker to heat Crabby’s mistela and laid out a huge bottle of grain alcohol, clay pots, clumps of cinnamon bark, a box of sugar—and that was that. They added a large mattress for the two women and a small one for their partner. He turned out to be an excellent sign painter, and they hung up a crafty poster reading DANCE OF CREATION. With no more advertising, they got ready to open the doors of the café-temple as soon as the sun set.

In that monotonous town, the slightest change resounded like a bomb exploding. Once siesta was over, the townspeople began their afternoon stroll on the sidewalk ring, the men signing to one another with glances to take notice of the poster while the women pretended to notice nothing.

Amado lent them an old gramophone, which had only one record—Gregorian chants. The flutelike, slow, monastic voices, escaping the testicles to echo in the head, could not inspire lascivious movements in Albina’s exuberant body. Even so, she clambered up onto the barrel and waited for the chanting to filter through the pores of her skin. No use. Those castrato throats could never submerge her in a sensual trance. Exasperated, she gave a whistle, long and shrill. In response came the rattling of hundreds of wings from the mountains. Soon a flock of parrots as small as sparrows invaded the hall. The hoarse tone of their chatter suggested they were all male. They clung to the ceiling, covering it with a green carpet, and began to imitate the Gregorian chant. Their voices, fused with those of the pious monks, caused the enormous woman’s flesh an intense chill that plunged her into the most dense and mysterious zones of her soul.

Seeing her move, the little man began to shake. He pushed down an erection with both hands and fell on his knees, red, tense, swollen, boiling, ashamed. Before he fainted, he managed to exclaim, “Forgive me, Madame Crabby!” Hearing herself “madamed” like that, Crabby also blushed. No man had ever treated her with such respect. She shook her head, sucked at her mustache, tossed a glass of water into his face, and gave him a friendly kick. “Come on, man, wake up! Our customers will be arriving soon.” Shocked, Amado muttered, “This is impossible! This woman can’t appear naked! She’ll cause heart attacks!” Albina, still dancing, stuck half her body out of the window facing the patio, squeezed her lips together, and sucked in air to make a grinding noise. A swarm of red bees came and covered her from head to foot. The deadly guardians!

When the sun dipped below the sea like a sinking ship, when the shadow of the mountains had barely painted the flatland black, a mob of silent men headed for the new establishment. It was the start of a rite that would be repeated week after week. These followers entered and packed themselves in around the barrel, getting closer and closer to one another, reducing edges and movements in order to take up a minimum of space. Finally they formed a compact mass of more than six hundred bodies. Not even a needle could thread its way through them. Crabby had to sell her mistela right at the entrance, pouring half a liter directly into each of their mouths. The sudden effect of the alcohol together with the hum of the parrots harmonizing with the Benedictine chant, to say nothing of the vestal’s body undulating under the buzzing mantle of killer insects, was enough to project them into another dimension, a place alien to space and time. There the individual became nothing in the magma of collective flesh and the lofty woman, a magnetic summit, everything.

Little by little, after detaching themselves one at a time, the bees began to fly around her. Thus appeared her hair, her white forehead, her nose all atremble, her mouth with its obscene lips, her neck, which smelled of incense. In the moment when the bees revealed her breasts, a cavernous sigh arose from the drunken mass, a mixture of satisfied visual desire and the pain of frustrated tactile desire. When her navel appeared, everything seemed to stop, as if the bees wanted to prolong the wait. Suddenly, in a buzzing explosion, the insects hiding the rest of her body also took flight in order to spin around with the deafening swarm.

Very slowly, as if it weighed a ton, the living sculpture raised her right heel until she touched it to her forehead. There appeared a great mouth, covered with dew and as red as the guardian bees. A dense saliva fell from the virile lips. Albina allowed her gluttonous winged servants to suck up the nectar from her sex and then, satiated, return to their hives. The knees of many oglers gave way, but held in place by the tightly packed mass they did not fall; they floated in the lake of flesh, showing only the whites of their eyes, like unconscious pelicans. At first light, the parrots stopped imitating the chanting and fell asleep. Amado stopped winding the gramophone, and with dictatorial gestures Crabby expelled the stupefied customers onto the curved sidewalk, where the women, wrapped in their black costumes, awaited them. The men, shot through with happiness, fell into their arms, weeping bitterly. The women had to carry them home like infants. Swallowing the couples, the doors of the houses, one after another, closed with tremendous bangs; shortly after they could not contain the frenetic squeaking of all the beds.

The two women, the beauty naked and the hunchback dressed, slept in each other’s arms from dawn to dusk, finally at peace. Crabby thought she could hope for nothing better; they’d found the impossible clean town where miracles could come to life, without thuggish and pestilential Drum Feet, with reverent men and discreet women. (After all was said and done, it was they who enjoyed the involuntary increases Albina aroused in their consorts’ private regions.) Also, the hatmaker had turned out to be a man of exquisite delicacy. When Albina slowly writhed like a serpent, giving off waves of angelic perfume and bestial heat that paralyzed the spectators, Amado had made a superhuman effort to overcome the stiffness that also invaded him and turned his head toward Crabby in order to gaze at her with a kind fool’s great big eyes and whisper, “I don’t want it to be for her; I want it to be for you, my lady!” Crabby didn’t understand very well, or rather didn’t want to understand what he meant to say to her. Nevertheless, she got goose bumps, and her mouth twisted into a smile that was not a grimace. She noted, with a sweet emotion she did not consider her own, that under the impact of the little man’s gaze the whiskers of her mustache were beginning to fall out.

The absence of death made everyone sleep a deep siesta. Muscles relaxed, hoping without hope to forestall the anguishing final cut. The lucky organism, full of confidence, allowed itself to be carried along by the current of sleep and entered a dense void. From Albina’s every pore flowed trickles of different perfumes, transforming her into a bulb in an aromatic forest. Crabby, herself all nose, became intoxicated from being up against that prodigious skin. From time to time, an outside tremor awakened her for a few seconds. Gradually, she realized that the hatmaker, purring like a cat, was sleeping pressed against her back. To herself she said, “Beat it, you impudent dwarf! What are you doing here, embedded between my shoulder blades like a tumor, when you know that the frontiers of our mattress are forbidden territory to you? An infraction worthy of punishment!” Even so, instead of inflicting the well-deserved kicks that would have returned the invader to his proper place, she curved her back and jammed her buttocks against the hatmaker’s belly. To ignore her own gesture, Crabby quickly went back to sleep.

One Tuesday, a free day, when in the suffocating orange afternoon sky the disk of the full moon was already visible, Crabby was awakened by desperate whining. Two surprises awaited her: first, Albina was not in the bed, and second the naked Amado looked more like a dog than a man, covered with fur, his mouth transformed into a muzzle filled with sharp teeth. Shaken by chills, as if two contradictory tasks were engaged within his in a bloody battle, he tried to speak, mixing words and spittle with his long, harsh tongue.

“Aouu! Oooo! My… mistress… heart… good wound… more than horizon… more than ocean… more than sky… the pain of a thousand daggers… heartbeats are your name… mother of my breath… Love!… Bloove!… Deathlove!… Barklove!… Aouu! Oooo!… Flower in my brains!… Gaze that burns us!… I breathe you in, I pant you, what pleasure, you on earth, you in the air, aroma, urine, sweaty hair, sweet mouth, lick your shadow, black shroud, roll around, die at your feet, whole, yours, yours, yours!… But the other one… Aouu! Oooh! The other one! Ay!… Pack of dogs, radiant, bite, violet moon, slave, fragrance, scalpel, ass, delight, voracious lasso, turbid whirlwind, absorb, demand, shock, corrodes, phallus, testicles, arrows, red-hot, gallop, fly, sink between your legs, lick and lick, silver vulva… Aouu! Ooooh!… Pack… Dog against dog… insatiable tunnel… fornicate… fornicate… Messenger of the bad moon… A thousand red lips!… I’m leaving! I don’t want to!… Tie me up, mistress!”

Drumfoot furiously shook his dirt-covered fur. He sniffed the bicycle’s seats, bent over the one that smelled of Albina, and with rapid movements of his narrow hips, his tail wagging like an insane metronome, he rubbed his red appendage until he flooded the leather with his acidic semen. He then licked up the sticky matter to quench his thirst. He tried to think. Despite trotting in a straight line, he’d returned innumerable times to his point of departure. So? What he had to do was to follow the twisty road without ever leaving it. Son of a bitch! To calm his rage and accept the order imposed on him, he carried on, urinating as much as he could. He had to possess her, to sever her jugular vein, to sink his muzzle into her anus and devour her body, beginning with her guts!

Crabby chained up the hatmaker-dog. When night became dense, the eyes of the half-animal glowed like hot coals. From his muzzle, green foam began to drip. His penis swelled at its base, looking like an electric bulb. It became harder and harder for him to speak; each word was followed by a bark.

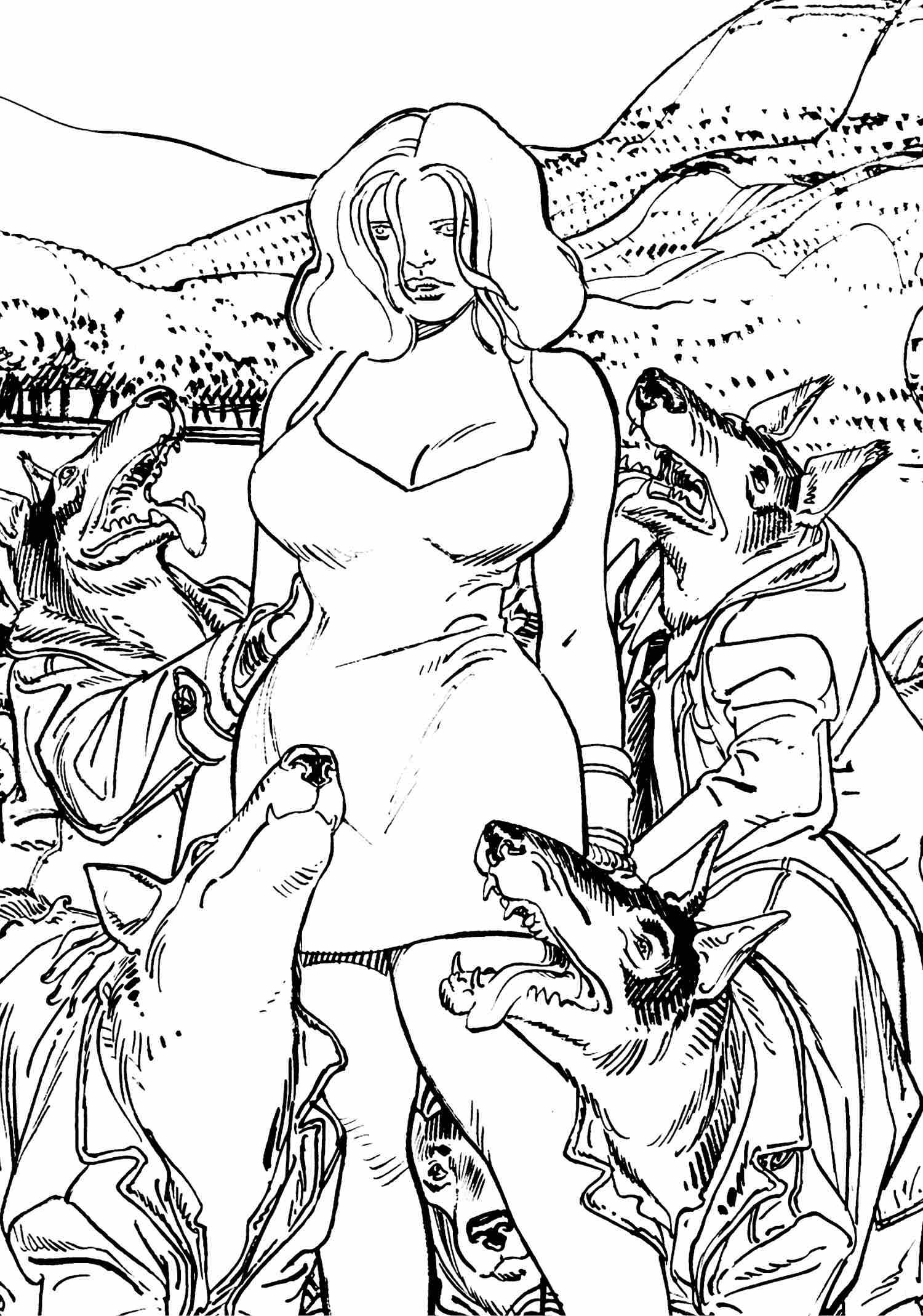

Madame Crabby had observed that Albina, despite her startling form, ate practically nothing, only a few grains of rice per day. In truth, she fed on the flesh she tore off her fascinated spectators. Every night, she bit at least seven—on the shoulder, at the base of the neck, or on the soft part of the arm. Barely any blood flowed from the wounds, and they healed quickly, turning into violet half-moons. The priestess’s teeth injected a canine virus that remained dormant for most of the month, waiting to come alive on the nights of the full moon, when it would invade arteries and veins. She and her enchanted victims were in two places at once. As humans, they seemed to attend the ceremony of the dance, hypnotized by Albina’s lascivious movements, the buzz of the bees, the hybrid chanting of the monks and the parrots, but they were nothing more than a tangle of empty forms, a mirage. Outside, in the hills, transformed into quadrupeds, they chased after a white bitch that from time to time howled in heat, and stopped to allow herself to be penetrated. Twenty, forty, a hundred males possessed her while they stretched their muzzles skyward trying to lick the moon. Insatiable, she extracted their semen again and again, until she saw them fall around her like sacks filled with soft bones. Now, on Tuesday, the day off, no one needed to be in two places at once. For that reason, Albina was not in the bed. The vixen was swallowing phalluses out in the mountains. Aouu! Oooo!

Amado pulled his chain taut with a snap. He held in a snort, hid his fangs, and muttered, “Can’t stand it… any more! Entire body… full semen! Sorry… mistress! Must… go! Please… follow me! You try… calm the hetaera!”

After climbing a rocky hillside, the zigzag path entered a high, hard plain. A hostile, sterile zone, home to snakes and playful spiders. For lack of flies they ate one another, producing with their triturating apparatuses a crackling sound like high-pitched giggles. It was there, far off, that the pack ran. Crabby huddled against a rock in order to spy without being seen. The granite, which still retained the intense heat of the day, covered her skin with blisters, but she withstood it all without moving. The white bitch stopped, raised her hind parts, lifted her tail, and offered herself to her pursuers. Pushing one another aside frenetically, they lustfully licked both holes. Then they possessed her amid a chorus of howls. Crabby poked her head out. That insatiable beast could not be her modest Albina! And yet, the chubby animal next to her proved that a human being could transform into a dog.

Crabby’s eyes filled with tears. The being who had once been her admirer running like an unfettered stallion to bite open a path through the ardent group and sank himself, giving nervous shakes, into the bitch’s posterior, and she felt as if a steel hand had torn her heart apart. Holding back her sobs, her sorrow, her jealousy, and her rage, she began to move forward, making huge leaps, overcoming the gravitational force of the plain. But as she freed herself from weight, time slowed down. With each step she rose thirty feet but at such a slow speed that it took her hours to reach the orgy. She was passed as rapidly as a spark by a filthy, stinking monstrosity bent low to the ground, leaving behind a plume of dust. One of its paws was swollen, and its back hair matted into the shape of a cockroach. Giving intense growls that advanced along the ground like a burning powder trail, it threw itself on the mass of dogs. The general stupor allowed it to reach the prey it so greedily desired, and it sank its fangs into her white back. She shook her body, making her aggressor fly back and forth like a fetid fan, but he would not open his jaws, intent on breaking her spine. The other dogs, insane now, began to cover him with bites. Howling with pain, he had to release his grip, but so powerful was his fury that he could fight all the others alone. Snapping implacably, he made the group scatter. The terrified canine mass fled, leaving behind a bloody trail the arid soil fruitfully absorbed. At the head of the pack ran the white bitch, with the flesh on her back open like a rose. Crabby made herself a shadow of the rock. There was no doubting it now: the butchering monster was Drumfoot. She regretted not having her iron bar to smash his skull. The danger was imminent, and while she could try to save her own skin by blending in with the ugliness of the landscape, which was not difficult given her own vile being, she could only pray. But to whom should she pray? To the old, bearded God who was hardly useful, even for removing ordinary calluses? She implored the only thing that, aside from Albina, had kept her alive: beer. “Oh, divine drink, just as you shooed sadness away from me, make that demon disappear. First save my girlfriend, then save my dwarf, and then, if you’ve got a gram of pity left, save me!” But beer seemed stone-deaf.

Three dogs, the most broken-down of the pack, were running with difficulty. Drumfoot caught up to them exactly where the plain ended and the foothills began sinking toward the plateau of Camiña. There he tore open their necks. Their corpses went rolling down the hillside and smashed against the first houses. For the other dogs, stiff with terror, the zigzag path turned to glue. Their aggressor, confident he would eliminate them and get the female, dashed after them with every bit of speed his three healthy paws and the fourth swollen one could provide. But he had to stop in his tracks and run for the hills, because a swarm of red bees suddenly blocked the way. Giving a snort of relief, the chubby dog left his neighbors, who with their tails between their legs were entering their houses. Surrounded by a halo of the guardians, he sought out Crabby so that they could return to town protected. On the peak of the highest mountain, the rapacious enemy howled at the moon, but a sole black cloud, pushed by a current of mountain air, came to hide her. Drumfoot trotted toward the desert, his head hanging, intent on waiting there, eating spiders, until the silver orb, full once again, offered him the damn bitch. Below, before Crabby’s sad eyes, Amado Dellarosa recovered his human form. Three men lay nearby, their necks spewing blood.

“The Lady has returned,” whispered the little man. “All the barking attracted her attention and she remembered us. How could we have stopped it? There she is now, the same as before, weaving her cloth among the four cypresses.”

Crabby could see, in the center of the plaza, under the thick foliage of the conifers, a dark shape that well might have been an old lady covered with capes and veils or an enormous black spider. Like a seagull hunting sardines, the day fell out of the sky to devour every shadow, except those of the cypresses, which became the dark heart of the light.

Crabby and Amado found Albina stretched out on her mattress, moaning as if emerging from a nightmare. The sheets were stained with blood, and at the center of her back was a deep cleft with jagged edges that revealed the bones of her spinal column. Crabby filled a clay pot with alcohol, ready to empty it into the wound, but as her friend wiped her eyes and gave a sensual stretch, the wound closed up like a suspicious oyster.

“Poor girl, does the bite hurt?”

“Bite? What bite?” answered Albina, smiling naively.

“The one that made you stain the sheets with blood!” grumbled Crabby.

“Blood? What blood?”

In the bed, the red had vanished. No sign of the bite remained. Crabby and Amado swallowed hard. Had it all been a dream? They ran to the door and sighed, first with relief and then with horror. There, among the four cypresses, was the Lady, weaving her cloth, and led by firemen carrying burning torches and the town band playing a solemn funeral march, a cortege passed by carrying on burros decorated with black plumes the three whose throats had been cut. Behind them, a group of bandaged-up men marched with difficulty.

Amado, huddled in a corner, biting his nails, observed the two women. Crabby, spellbound as usual, but with a sigh of concern, watched her naked friend charmingly sweep away the excrement of the parrots, who had made a home of the ceiling. Carefree and whistling a merry tune, Albina seemed not to remember her nocturnal escapade. In the face of such a false calm, the little man scrambled to the top of the barrel and began to screech, “Enough! Let’s stop playing the fool! The problem is serious! You, Albina, must know that you turn into a lusty bitch and that you infect the men of the town with your bites! You, Lady Crabby, must stop this! If you don’t, with every full moon the Lady will fill her belly with murdered dog-men! It will enhance her appetite, and she’ll end up devouring everyone!”

When Crabby told her, in full detail, what she’d seen the previous night out on the plain, Albina burst into tears. “Dear friend, dear heart of mine, I owe you my life. I know you’d never slander me, but understand that you may trick yourself and lie without intending to. Our reason is like a solid boat sailing on the infinite ocean of dreams and madness. Don’t believe your dark part, look at me as you used to look at me. I am a woman and not a lusty bitch. I do not eat human flesh, and no man can turn into a quadruped. You love me, you cannot invent such horrors. It’s this hypocritical dwarf who’s got you hypnotized. He wants to separate us, so pay no attention. Let’s get on our bicycle built for two and get out of here. There has to be a place where there are no men!”

Amado became desperate as he watched Crabby weaken in the face of her friend’s tears and whisper warm “forgive me’s” as she rocked her in her arms like a gigantic sobbing baby. Without realizing or desiring it, Albina was one being at night and another by day. And now, Amado had to present irrefutable proof to keep all the men in town from being infected. No words could convince Crabby; he would need material evidence. But where would he find it during the daylight hours? “I hope this works!” he shouted, and shut doors and windows and blocked all the cracks light peeked through. Amid the protests of the parrots, he hung a round mirror from the ceiling and focused a flashlight on it. Once he’d achieved the lunar effect, he used all the power of his will to unleash the virus; it worked. His mouth turned into a muzzle, fur covered his skin, and his arms turned into dog legs. In a mix of barks and human words, he said, with difficulty, “Do you see, Albina? A human being can turn into a dog. You and the moon are the cause.”

Crabby turned off the flashlight with a kick and ran to open doors and windows. The light enabled Amado to recover his human form. Convinced, Albina became depressed. “I thought I was what I am, but in reality I’m still what I was. And that which I was, well, I don’t know what it is. Perhaps some day I will know. Then I’ll be what I shall be, but I’ll stop being what I am now. And ceasing to be what I am now horrifies and terrifies me. Help me, please, you two!”

Crabby hugged her friend, covering her huge breasts with tears and snot. “I don’t want you to change! We were fine just the way we were! Now that we know everything, we can tie you up, with your permission, on nights of full moon. We’ll chain you, gag you, blindfold you, seal your ears with balls of wax, and close down the hall! And every one of those he-men in heat who come around to sniff and bark, well, we’ll run them off with my iron bar! You do not have to know what you were or be ashamed of it! Your past is of no importance! The cat is not his tail!”

Amado cleared his throat politely, interrupting the embrace. “Ahem, well then, ladies. A tail wandering around is certainly not a cat, but if it’s attached to the animal’s backside and you step on it, you’ll see that the tail is very much the cat. Since this problem falls under my area of expertise, allow me to give you some advice. If we consider that the transformation from lady to dog is not a curse but an illness, we can try to cure it. In nature, every venom is born alongside its antidote. Lady Coughard, the witch doctor, can help us. It’s true that at the age of a hundred and forty-three she lives with the other old folks in the abandoned mine, but she’s not above peeking out when people bring her pink smelts. Since she eats clay all the time, that little treat drives her wild.”

Fearing that they’d be attacked by Drumfoot, they let Pinco, the deaf-mute mule driver, feel up Albina’s body for an hour as payment for hiding them among his mules and bringing them to the beach. Tucked away next to the coastal rocks, they spent several hours trying to hook half a dozen fish. The regular silvery smelts, with their tapered bodies and complete lack of intelligence, came in schools to devour the bits of bread at the bottom of the creel-trap, and the fishermen dumped them back into the sea like shiny vomit. The pink ones on the other hand were very scarce. They always swam alone, so nervous that they could eat the bait and flee before the door of the trap closed.

Amado, Crabby, and Pinco—who was helping them, not because he was an obliging soul but so that he could lay his greedy hands on Albina’s buttocks, using the jolt of the waves as a pretext—all lost hope, got out of the water soaked to the skin, and moved into the sun. Albina, sighing compassionately, began to dive. A pink smelt, with its lynx eyes, swam to look at her, or rather to adore her. She opened her mouth wide, and the little fish swam in, curling up on her tongue as if it were a nest. Just like that, in under an hour, she caught the six needed to seduce Lady Coughard.

Opposite a precipice on the steep hill, the abandoned mine opened like the mouth of a gigantic mummy; instead of a shriek, a cloud of orange dust floated out from it. The wasteland’s heat caused whirlwinds swirling around the feathers of dead seagulls, as sharp as razors. Carrying the smelts, still alive in a flask filled with salt water, they stood shouting for a good while outside the dark maw but got no response. The whining chant of a hundred or so old folks made the tongues of dust tremble. Finally, opening her way through the copper-colored columns, came the witch doctor, followed by an armadillo. Seeing the appetizing offering, she spit out a ball of clay, which the animal began to lick greedily. She seized the flask with her claw-like fingers and, possessed by spasms, swallowed the fish whole along with the salt water. She fell seated on the burning soil, but her parchment-like skin suffered not at all. She patted her swollen belly, belched, and began to laugh as if she were drunk.

“Many, many thanks, little girls and even littler boy! Those pink smelts restore my taste for life after so many years of eating dirt. Before I was an empty thing, I didn’t exist, but now at least I have a full stomach digesting with pleasure. Soon I’m going to put out a good, soft shit and not expel gravel, so that it cancels my sterility and makes me create. Create what? A fetid nest for larvae. Hallelujah, shitters of the world! We have a purpose; we are the mothers of worms! Do you need something from me?”

Crabby, disgusted by the old crone, put her protective arm around Albina and whispered into her ear, “Don’t despair, darling. We’ll never age like that. Luckily, just opposite our café-temple, we have the Lady. When our flesh begins to sag, the two of us we will tangle ourselves up in her web.” Amado explained the problem of Albina and the dog-men to the witch, which caused her to have an immodest orgasm. Then she answered, in sentences so broken that they sounded like a rooster crowing.

“Stop worrying. Problems are only disguised solutions. A long time ago, before the Incas, there lived in these wastelands the Paracas. Among the many divinities they worshipped was a bitch-goddess—an animal with twelve teats who gave white and black milk at the same time. No one knew when they sucked which teat would give food and which would give poison. Her followers immunized themselves against the dark liquid by eating a flower called shigrapishcu, the solitary product of a cactus that only blossomed once every hundred years. Sometimes the remedy was worse than the sickness. For every two people who ate the shigrapishcu, one would die! Do you see what you’re exposing yourself to, milky girl? To be cured you have to want to be cured, then know you can be cured, and finally accept the changes that health brings. Don’t fool yourself. If you manage to find the flower and eat it without dying, you will never be the same. And by changing yourself, the others and the world will change. Your new eyes might make enemies or victims of friends. Everything is possible. On the other hand, if you decide to do nothing, you will end up raped and beheaded like all the other dogs. What do you say? I see you dithering. You’ll never be able to make a decision! It would be better if you killed yourself by jumping off a mountain right now!”

The armadillo climbed up the old woman’s body as if it were a dead tree and arranged itself on her bald head like a hat. The two women and the little man stood still, waiting for the image to dissolve like a bad dream. The old woman’s hoarse breathing turned into a toothless guffaw, and a parade of naked nightmare figures all covered with clay began to emerge from the mine. Some dragged themselves along, others limped, most danced with grotesque gestures, all marching down toward Camiña. Lady Coughard stood up, took hold of the armadillo and ordered it, “Roll up, Quirquincho!” The animal wrapped itself up in its shell of bony plates and turned into a ball. With great skill, the witch tossed it at Albina, hitting her right in the forehead. Caught off guard, Albina stepped back, her face covered in blood, and almost fell into the precipice, managing to hang onto a dried-out bush at the cliff’s edge. “Don’t help her, assholes!” thundered the witch, paralyzing Crabby and Amado with a strange gesture. Then she crawled to the edge of the abyss and said to Albina, “Big coward! Dreamer! When are you going to stop clinging onto what you aren’t? Eternity without change is a poisoned gift! The Holy Lady has recovered her memory and is now calling us! Obey her as we do! Let go of this world!” Grabbing the armadillo by the tail, she used it as a hammer to beat Albina’s fingers. “Take that and that! I told you to let go, you freak!” Roaring with rage, Albina swung her body, kicked her legs, and did a flip to land on her feet in front of the witch. Lady Coughard looked at her mockingly.

“Now do you see you aren’t a coward, girl? And you aren’t a sheep either. Don’t let yourself be beaten; you know how to fight and to win. You deserve my help!” With another wave of her hand, she lifted the paralysis freezing Crabby and Amado. “Listen to me, all of you. Thanks to the mining companies whose slag has turned these lands into a hostile desert, there is only one sacred cactus left alive. According to my calculations, it will flower in four days. You only have that short amount of time to find it, because when the shigrapishcu opens, it only lives for ten seconds. Then it disintegrates in a luminous explosion, giving off a perfume that is so penetrating it makes anyone who breathes it insane. If you don’t get there on time, you’ll have to wait a century for another. The plant is small, no more than four inches tall, but because it’s lived for thousands of years, its roots stretch under the dry crust hundreds of miles in diameter. The only way to reach it is to find one of those long roots, uncover it and follow it like an electric line. I’ll give you Quirquincho. If you walk in a spiral pattern, he will find one using his powerful sense of smell.”

The long, reddish conga line made up of the old people moved off down the mountain, zigzagging along the narrow path. “Neither the brain, nor the heart—your skin will tell you the way!” shouted the witch doctor, and ran limping toward the clay-covered mass of bodies and let herself be swallowed up by it. Albina, filled with a strange power, furrowed her brow: “I understand. I must not seek the cure thinking only about myself. I have to think about the others. If the evil comes from within me, when I eliminate it within my soul, they will stop being dogs. And I will become what I must become. I’ll seek the shigrapishcu! Come on, Quirquincho!”

“And what about me?” thought Crabby. “Does she think I’m going to let her go by herself? Her fate is mine, and that’s that!” Four days to find the solitary cactus in that immense, blazing hot wasteland that unfolded like the skin of a dead iguana, a hell into which even the red bees would refuse to accompany them, depriving themselves of the sweet, aromatic sweat of the woman who’d dominated them. The repugnant Drumfoot also awaited them there, intent on tearing them to pieces. Finding the cactus seemed an impossible task, suicidal. Nevertheless, Crabby, without her usual snorts of indignation, trotted after Albina. When they reached the plain, Crabby took the lead and walked forward with her arms spread, her chest thrust forward, and her chin out, as if with that stance she could protect her friend from monsters and demons. Feeling abandoned, the hatmaker started to return to town, but after a few steps he made a half-turn and shouted to his partners, “Hey, ladies, wait a minute. Let me get some barrels of water and three burros to carry them!”

Albina, entering the desert, didn’t even turn her head. But Crabby stopped. She dried the perspiration on her face with a clumsy gesture to hide her intense blush. Her heart began to beat more rapidly when Amado announced his decision to follow them. “Wait, Albina, our partner is right. Without water we’ll die in a single day in this oven. Here, in the shade of a rock, we’ll wait until he gets back with the water.” As soon as her friend sat down next to her, she shouted in a rude tone that hid an intense sweetness: “Hurry up, Mister Dellarosa, and don’t waste any time! We’ll give you half an hour to get back with the water and the burros. But we won’t wait a second longer! And while you’re at it, please bring along my iron bar.” Shouting his fervent obedience, Amado started running toward Camiña, trailing an angular tail of dust.

All things come along following my footsteps, barking desperately…

and I am a walking dead man.

Pablo de Rokha, “Winter Steel”

With all the speed his short legs could muster, Amado passed through Camiña’s western entrance. He was winded by his efforts, but his shortness of breath became even shorter when he saw old men and women tossed all over the street like clay dolls. The maddened bees flew from one O-shaped mouth to another, drinking saliva that stank of swamp. The townsfolk added their nervousness to that of the bees; the spectacle of all those cadavers—their grandparents of mythical immortality—made them feel like towers obliterated by a lightning bolt. Those dried-out bones, a parched ocean, transformed the circular town into a ship manned by a crew sentenced to death. And it would be impossible to rent burros from Pinco! Loaded with three or four corpses each, the animals paraded in single file toward a bonfire blazing in the cemetery. The stringy flesh and sun-cured skin of the dead sent toward the sky a thick black smoke that seemed to dissolve into flocks of buzzards. The birds swooped down to dig among the ashes, only to fly up again carrying in their claws porous bones that exploded like firecrackers.

The café-temple, left empty, with its doors and windows shut, was invaded by beams of light. In fleeing from their prison, the parrots had pecked through the roof. Perhaps as a kind of protest, they had emptied their bowels before flying away, and a carpet of coppery-green scarabs enjoyed the sinister banquet left for them. Amado, his nostrils sealed with thumb and index finger, filled a big bottle with water, grabbed Crabby’s iron bar along with three gold nuggets his father had left him as an inheritance, and, thus loaded, went back out to the street, thinking he’d never return. A group of women chased after him, throwing shoes: “You brought those women here, you damned dwarf, and they brought in death. It’s all your fault! Just look at what you’ve made of our husbands!” As he fled, Amado saw individuals growling in dark corners, squatting down, leaning on their knuckles, using their arms as forelegs. Their naked torsos had patches of fur, and their jawbones, grown huge, stretched out their lips. The hatmaker realized that he, too, was experiencing the same mutation—mouth turning into muzzle, skin sprouting fur, ears going pointy. He felt a tail jutting out of the base of his spine. The malady no longer needed the discretion of night to manifest itself; it now dared reveal itself by day. Soon those men would be dogs through and through.

With difficulty, since the iron bar weighed as much as the water, he climbed the steep path. The women, barefoot now and afraid to walk on a desert floor covered with sharp stones, stopped following him. But almost immediately, a pack of men galloped after him, their shouts turning to barks. He tried to speed up, but when he reached the plain, the pack was upon him. Thinking they were going to eat him, the little man tried to wave the iron bar around, but he lacked the strength even to lift it high. Fleetingly, he thought of Crabby with fervent admiration; she waved that heavy weapon around as if it were as light as a feather. Paying him no attention, the monsters ran into the disappearing horizon, jets of excited foam flying from their mouths. Near the vanishing point, tiny now, they began to dig holes with their paw-hands where they could bury themselves to escape the heat, waiting for the cool wind of night.