BENJAMIN SPOCK’S cheerful suggestions on baby and child care encouraged many young parents to believe they could somehow meet the challenges of rearing multiple children. But in school district offices across the country, the surging birthrate was prompting a crisis atmosphere that would dominate educational policies for almost two decades. Unlike parents, obstetricians, and pediatricians, most school officials and teachers did not have to deal with the impact of the Baby Boom from the time of its inception in January 1946. It would be early in the next decade before the first cohort of Boomers reached school. On a series of bright, late-summer days in 1952, however, the Boomers and the American school system were introduced to each other in the educational equivalent of the Normandy invasion.

A year earlier, school personnel had received a preview of coming attractions when a mixture of the youngest war babies and the oldest Boomers had crowded schools designed largely for low prewar birthrates. Now, in 1952, the first class made up entirely of Boomers, the future high school class of 1964 and the college class of 1968, pushed public school attendance over the 34 million mark amid projections that even this staggering number would increase by an additional 50 percent by the end of the fifties. (In 1940 school attendance had been 25.4 million.) Unlike an enemy sneak attack or a natural disaster, the initial surge of children into first grade occurred with plenty of advance warning. But the heroic responses of a nation at war had perhaps worn thin in peacetime as half-measures, wishful thinking, and competing educational demands produced an educational crisis that at times threatened to spin out of control. For example, in the early 1950s the percentage of teenagers remaining in high school until graduation was soaring just as the Boomers hit the lower grades, forcing superintendents to create stopgap measures at opposite ends of the educational ladder. Semi-rural areas that had made do with a single consolidated school were now burgeoning suburbs requiring six new elementary schools at the same time. Low prewar birthrates had produced a meager pool of new teachers—just as the need for their services exploded.

As late summer 1952 turned to autumn, a nation concerned with Soviet spy rings, a new addition to Lucy and Ricky’s television family, and the stretch drive of the baseball season would find it difficult to miss the media attention to the emerging crisis of overcrowding in the schools. Magazines, newspapers, and television news began running pictures of cute young children doubling up two to a desk, sharing textbooks, and jamming lunchrooms. Harried superintendents and principals showed visitors classrooms bulging with forty or fifty pupils, and predicted even higher numbers to come. Extensive parochial school systems in Northeastern and Midwestern cities dispatched nuns from retirement homes and shortened training periods for young novice sisters to cover gaps in schools that often exceeded sixty students per classroom.

While parents and school officials fretted over this classroom overcrowding, more than a few Boomer children saw the experience as a memorable adventure. Teachers might see row upon row of cherubic faces that created multiple opportunities for calling a pupil by the wrong name, but the children took the situation in stride. A girl alternately called Joan, Jean, or Jane, or a boy addressed as John, Joseph, or Jerry, realized that adult teachers were not all-knowing and teased one another with their “alternate” names, which brought laughter all around. Some Boomers adopted a sort of perverse pride in the size of their class enrollments, especially when the youngest students eyed the much smaller class sizes in the upper grades. The older kids might be bigger and stronger, but the Boomers had sheer numbers on their side. Some level of unique group identity may have been developing well before most of this generation had any idea what the term meant.

Despite children’s lack of concern, adults saw these school problems as a major issue for the nation’s future. An extensive editorial essay in the October 1952 Life magazine focused on overcrowding in one New York City school. Max Francke, the principal of a school with 2,011 students in a building with a capacity of 1,470, was engaged in an endless game of musical chairs with his Boomer kindergarten and first-grade pupils. “My teachers are tired, the crowding is getting them down, there are so many five and six year olds, and they will move up through the higher grades next year.”

All students at the school were required to wear paper name and address tags while mothers were given a printed timetable to let them know when the teachers would bring their children to the school door. Francke noted that the enrollment of 245 in the second grade was dwarfed by the 430 first-graders who overwhelmed school capacity. “Over 500 children are getting five hours less class work than the law requires, and they confuse parents by entering and leaving at odd hours” in the first stage of a split-shift configuration. One mother who had two children in different shifts complained, “For years I’ve been looking forward to getting both kids from under my feet at the same time. Now that isn’t happening.”

As traditional school buildings were engulfed by the surging enrollment, officials opened classrooms in town halls, firehouses, and church basements. A few desperate districts turned school buses into classrooms between their pickups and deliveries. The Linda Mar housing estate, fifteen miles east of San Francisco, rented eleven of its homes as schools for $850 a month. A Long Island developer demonstrated his civic spirit by paying construction crews to work overtime and weekends to prepare ten houses as classrooms in time for the post–Labor Day surge of new pupils. As classes met, tractors were still smoothing dirt in front yards. Partitions were temporarily left out of construction in order to provide classrooms with enough space to hold the swelling student population. The pastor of a suburban Philadelphia Catholic parish purchased a house across the street from the school, placed the first-graders in the building, and received township provision for an all-day crossing guard to shepherd six-year-olds across the street to use the main building’s lavatories.

The national shortage of classrooms, which reached 370,000 by 1953, was matched by a burgeoning teacher deficit which one educational writer attributed to “matrimony, maternity and more money elsewhere.” During the ensuing decade, nearly 200,000 teaching appointments would be left unfilled at the close of each academic year, yet the most sensible solution to attract new people to the profession—substantial pay raises—always seemed to be the last resort. West Hartford, Connecticut, which counted 109 unfilled teaching positions in a staff of 400, encouraged new applicants with a community square dance, help in finding housing, a Rotary Club welcome luncheon, and gifts to anyone who signed a contract. The PTA pooled its resources to locate families willing to take in teachers as temporary boarders at little or no rent. On a national level, magazine advertisements and television public service programs portrayed teachers as key personnel in the expansion of the American economy and the defense of liberty. Placed among color photos of new refrigerators and ranges, the Norge Corporation announced that “American elementary schools are now short 120,700 teachers—this means overcrowded classes, half days, and other shortcomings. Write for practical information that you can do as a concerned citizen.”

Journals specializing in educational affairs devoted entire issues to the Boomer tidal wave. In “Our Children Are Still Being Cheated” in its October 1953 issue, the Elementary School Journal warned that worse problems were on the way as “the number of children will increase another 1.6 million this year, and by 1960, there will be 10 million more students than today.” School districts were building an additional 97,000 classrooms, but even that campaign would leave 60 percent of all classes overcrowded, with 20 percent of schools unable to meet even minimal fire safety requirements.

The Journal pointed out that mere stabilization of class sizes at current overcrowded levels would require 425,000 new classrooms by the end of the 1950s while university teacher training programs had produced only 46,000 new elementary teachers for the 118,000 additional positions that school districts had created. These equations meant that the best-case scenario for the immediate future was an average class size of 45 children, with even larger classes if the teacher gap continued to worsen.

The surge of new students consigned large numbers of children to a learning environment of dilapidated classrooms manned by overtaxed teachers. Yet two compensating factors emerged to make the school experience of the 1950s and 1960s much less grim than initially feared. First, a massive school construction effort, even if plagued by shortfalls, offered the opportunity for a relatively large number of Boomers to attend schools that were much more modern and cheerful than those from their parents’ childhoods. Burgeoning suburban communities constructed gleaming, airy, attractive schools with glass walls, offering a vista of pleasant grounds. Banks of new fluorescent lights brightly illuminated classrooms on the most dismal winter days, and movable desks replaced the regimented rows bolted to the floor. New schools often featured a single-floor format where classrooms were interspersed with spacious arcades and growing numbers of special-activity rooms. School architects found themselves free to experiment with dramatic innovations that spelled the end of the last vestiges of the “little red schoolhouse.”

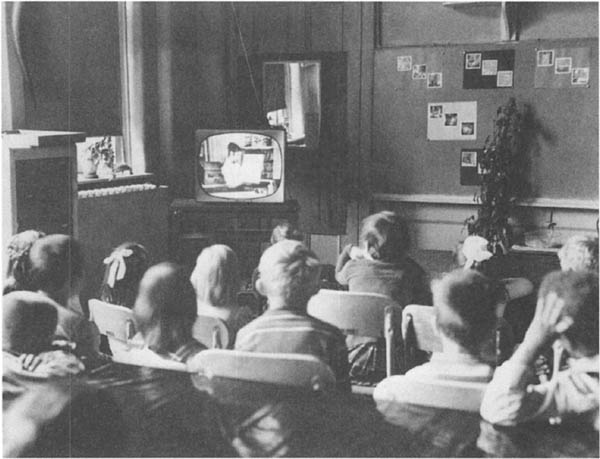

A second potential benefit of the Boomer surge was a greater receptiveness toward the use of new technology to at least partially counteract the ongoing teacher shortage. Tape recorders, portable record players, transistor radios, and enhanced filmstrips offered significant opportunities to create new learning environments. The most frequently discussed new educational technology was the emergence of television as an increasingly dominant medium. As families flocked to buy televisions that would penetrate the majority of American households by 1954, a national debate erupted over the role of the instrument in the learning process.

One national news weekly provoked substantial public response to an article titled “The 21-inch Classroom,” which suggested that “If it lives up to its promise, television will revolutionize teaching as nothing else since the American public school was established. Television may alleviate the critical teacher shortage, as television in both closed-circuit and over-the-air educational and commercial stations emerge. Despite the possible dangers in television, the results are so encouraging that the number of schools using it is doubling every year, and the time they allot to TV instruction is rising rapidly.” One example cited was the Hagerstown, Maryland, school district, which developed a closed-circuit system. By 1957 it was providing all children from first to twelfth grades with televised lessons from a central studio in which a teacher could reach seventeen hundred students at once.

Much of the funding for experiments in instructional television was provided by major Ford Foundation grants. Some parents believed their children were already getting too much television at home, and more than a few suspected that the new medium might someday replace conventional teachers altogether. Yet in an environment where the teacher shortage was projected to reach 500,000 by 1965, televised instruction gained increasing legitimacy.

As a growing number of educators envisioned a not too distant future when “a special device will enable pupils to interact with the televised teacher hundreds of miles away,” most 1950s children spent their school day learning from textbooks that were not greatly different from the lessons their parents had received. The centerpiece of instruction at the elementary level was still literacy teaching, and in many cases this meant an encounter with a “typical American family” featuring Dick and Jane, their toddler sister Sally, Spot the dog, Puff the cat, a pipe-smoking father, and a pretty, well-organized mother. Short repetitive sentences, such as, “See Spot. See Spot run. Run Spot Run,” interspersed with colorful pictures of family activities and interaction, began the great adventure of reading in an era when the printed word had far less competition for attention that it would in the twenty-first century.

While many parents’ groups and child psychologists warned of the dire consequences of television’s effects on Boomer children, much of the educational establishment welcomed the video revolution as a means to broaden pupil horizons and help overstretched teachers and administrators. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

The repetition pervasive in reading instruction was rivaled by mathematical activities. In an era when personal calculators were still decades in the future, a passerby could have heard children shouting in unison a numerical litany based on “times tables” (four times six is twenty-four, five times six is thirty, etc.), suggesting that with enough repetition a child could become a human calculator with an array of correct answers readily on call.

If the typical fifties elementary school curriculum concentrated on reading and mathematical skills, the school day was peppered with a variety of other activities. The recently ended world war and the ongoing cold war with the Soviet Union, China, and assorted client states encouraged attention to history, geography, and basic government structure (often called “civics”). American history was presented in the traditional heroic model of triumph over British tyranny, struggle for existence on the frontier, and the rise of cities and industrialization, but two major themes differed substantially from the experience of the Boomers’ parents. First, of course, was the enormous impact of World War II, which seemed to straddle a position between history and current events. Since students were often encouraged to use parents as resources for war-related projects, and virtually all teachers had experienced the conflict on some personal level, the period could often occupy a significant portion of the history curriculum in the upper grades of elementary school.

The second change, just beginning to emerge in the 1950s, was a consideration of individuals and groups that had been underrepresented in earlier generations of history teaching. The exploits and accomplishments of Native Americans, African Americans, and women were now beginning to be interwoven into the tapestry of the American experience, even if the process was often tentative and occupied a relatively small portion of the narrative.

A category increasingly identified as social studies was heavily influenced by the nation’s sudden emergence as a superpower and the reality of its competition with the Communist bloc. Civics courses often presented American democratic government in sharp contrast to the tyranny of communism while geography texts sometimes contrasted the experience of a typical American family with the far harsher existence to be found on a Soviet commune. Geography textbooks with titles such as Our Latin American Neighbors emphasized the strategic products of these nations; textbooks on European geography frequently displayed bold lines of demarcation dividing Western Europe from the nations behind the Iron Curtain.

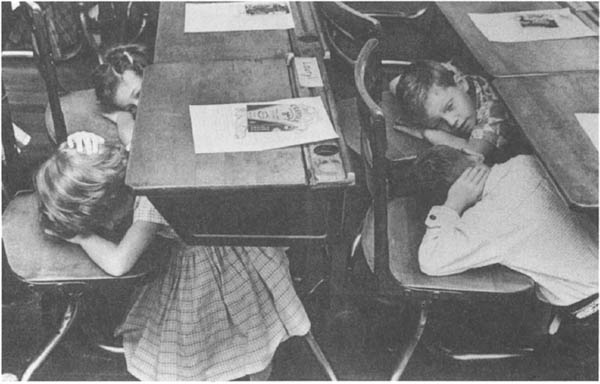

Probably the most disturbing element of the 1950s social studies curriculum was an experience that was never tested or graded. This was the grim preparation for a possible nuclear attack launched from the Soviet Union. One of the most commonly shared experiences of almost all early Boomers was the shrill wail of sirens attached to the ritual known as “duck and cover.” World War II—era pupils had been the first American children exposed to the possibility of enemy air bombardment of their schools and homes, but after the initial panic following Pearl Harbor, the threat of a serious Axis bombing of the mainland United States receded to the point that air raid drills became little more than a welcome relief from a scheduled spelling test.

It would be the Baby Boomers, the first cold-war kids, who would see animated and live “educational” films that graphically demonstrated what an atomic bomb could do to a largely defenseless public. Some classrooms featured posters that displayed an aerial map of the nearest major city with concentric rings showing the level of destruction to be expected if a nuclear weapon were dropped in the center of the city. Teachers affecting a matter-of-fact detachment sometimes helped pupils calculate the severity of damage to their school or neighborhood, depending on its distance from ground zero. Children went from week to week without knowing when the eerie whine of sirens would announce reality, signaling the end of the world they knew.

Most schoolchildren of the cold-war period became experienced veterans of duck-and-cover activities. Even the animated advice of Bert the Turtle and the suggestion that part of the exercise was in preparation for a natural disaster could not conceal the grim possibility of nuclear war. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union never deteriorated to the point where the protection of school desks against atomic attack was tested. Yet, just as the oldest Boomer children settled into their sixth-grade routine, a real threat from the skies rocked the American school system to its core. On Friday, October 4, 1957, the Soviet space agency successfully launched the first man-made object to achieve orbit around the Earth. A Soviet R-7 rocket lifted from the ground with a thunderous roar as five engines supplied over a million pounds of thrust. Speeding at more than 17,000 miles an hour, the rocket reached an altitude of 142 miles and released a 184-pound sphere studded with four antennae. Seconds later, radio signals beamed toward Earth with a distinct beeping sound. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev soon announced to the world that the age of space exploration had begun with a “demonstration of the advantage of socialism in actual practice.”

The launch of Sputnik was a fantastic propaganda triumph for the Soviet Union. Every ninety-six minutes a vehicle bearing a hammer-and-sickle insignia passed over the planet in an orbit that allowed Americans from New York City to Kansas an opportunity to glimpse mankind’s first tentative baby steps into the cosmos. American newspapers and commentators gave a grudging compliment to their ideological rivals: “Orbiting with an eerie intermittent croak that sounds like a cricket with a cold, picked up by radio receivers around the world, Sputnik passes through the stratosphere on an epochal journey.”

When American children returned to school the following Monday, the repercussions of this achievement were already creeping into the classroom. During much of the preceding decade a significant portion of American educational thought had argued that American children were exposed to a curriculum that sacrificed essential academic skills in favor of socialization, peer acceptance, and marginally beneficial school activities. Now books such as Why Johnny Can’t Read, lamenting the shortcomings of American schools, were joined by What Ivan Knows That Johnny Doesn’t and The Little Red Schoolhouse, which promised to divulge what Soviet schools did right. Life magazine spent much of the 1957–1958 school year publishing cover stories on “The Crisis in Education,” filled with comparison photos of Russian and American school activities. One pair of images showed a group of serious-minded Soviet children huddled over an imposing array of scientific equipment, contrasted with an American classroom where carefree students were learning the newest popular dance. An educational journal noted that “up to Sputnik, Little Ivan, just like little Johnny, went to school period, no story, no comment, and no one gave a hoot about the fact that Ivan was learning not quite the same thing in school as Johnny. Now we have the ‘Cold War Classroom’ with press lines almost to the point of hysteria, as average Americans cannot believe that the educational effort of ‘backward Russia with savage Communist masters’ could be so significant and important.”

Events over the next few months merely added to the growing sense of alarm. On the eve of the anniversary of the Russian Revolution in early November, Sputnik II was launched, and the thousand-pound sphere carried the first space passenger, a female terrier named Laika, who was placed in a pressurized cabin equipped with food dispensers and water. Laika did not survive a partial power failure, but the sound of a dog barking inside the massive craft scored another impressive Soviet propaganda triumph.

A December 1957 American launch attempt produced a stark contrast in space technology when the Vanguard rocket exploded into thousands of pieces, barely fifty feet above the Cape Canaveral launch pad. On the last day of January 1958 the United States salvaged a measure of pride when an army Jupiter rocket carried an 80-inch-long cylinder named Explorer I into successful orbit. America had entered the space race, and Explorer achieved an orbit an impressive 1,563 miles above Earth. Yet its 30-pound, six-inch-diameter size seemed puny, and the launch did little to convince many Americans that Soviet schools were not outperforming American institutions. While many proposals for educational reform were focused on colleges and high schools, millions of Boomer elementary school children would be affected by Sputnik.

Salt Lake City became one of the first school districts to add Russian to its elementary school curriculum. Children at Bonneville Elementary School were profiled studying the rather exotic language by using Soviet textbooks, since no Russian texts were currently printed in the United States. Because Soviet texts were filled with pro-Communist propaganda, questionable paragraphs were cut out with razor blades. One cheerful pupil insisted, “This will help me get a good job with the government.” In Oklahoma City, TV station KBTA gave Russian courses for grade-school children three days a week while Portland, Oregon, elementary school kids peered through a telescope set up in a teacher’s garden as every morning at 6 A.M. they watched for Sputnik to pass over.

The Sputnik launch produced a barrage of calls for more toughness and rigor in American elementary schools. Substantial increases in foreign language, physical education, and science, down to the first-grade level, could be accomplished by cutting back on art and music instruction. Homework assignments could be substantially increased. The school year could be lengthened, and calls for that bane of childhood, year-round school, floated from one community to another. Yet most of these urgings proved to be less intrusive than children feared or educators hoped. Much of the new science education in elementary schools tended to be more fun than drudgery. For example, a Riverside, California, elementary school quickly developed a science fair based on space exploration. A photo image shows a crowd of children, faces half hidden under cardboard space helmets, constructing a thirteen-foot-high cardboard rocket, control panel, and launching pad designed for a mock trip to the moon, while their delighted teacher insists that such activities will encourage students to “think mathematically.” Many young children were now determined to become astronauts, and new heroes were the handsome rocket scientist Wernher von Braun (a German refugee) and soon the astronauts Alan Shepard and John Glenn. Year-round schools, shorter vacations, and lengthened school days sounded frightening to an average ten-year-old Boomer child; but, in a mix of wishful thinking and almost adult perspective, these same ten-year-olds reasoned that their teachers too would not welcome year-round school and longer school days. Recreational and amusement interests would challenge the loss of revenue, and parents could never take a family vacation if holiday periods were staggered among different grades. In this case the kids were more on target about the real world than many educational theorists. While some school districts tinkered with their schedules, most Boomer children would retain their long summer vacations and mid-afternoon dismissals. On weekday afternoons and evenings, weekends, holiday breaks, and summer vacations, these postwar children would enter a world far removed from school. Their play and recreation would be nostalgically remembered a half-century later.