SOON AFTER Labor Day 1963, the promises and challenges of the great postwar birth surge coalesced in a major milestone. As beaches, campgrounds, and amusement parks became noticeably quiet, the children returning to school from kindergarten to the twelfth grade were, for the first time, all Boomers. Predictions from the forties and fifties that the surge in births would eventually affect every aspect of the public school system had now become reality, and there was no hint that the situation would change in the foreseeable future. One small consolation in this ongoing demographic crisis was that the United States now had a school population that completed the entire sequence of grades up to high school graduation in overwhelming numbers. Thus projections for future enrollments would be accurate enough to plan for faculty and facilities expansion if teachers could be found and funds raised.

Yet in the fall of 1963 the educational establishment, the Boomers, and their parents were about to enter uncharted territory: students had a legal right to education through high school, but they had no such right to higher education. Each public and private institution was relatively free to expand as little or much as it chose, regardless of the needs of the Boomers who were about to seek admission to its campus. As Boomer seniors settled into their twelfth-grade rituals and routines, many faced not only the opportunities and challenges of their final year of traditional public education but also a complex national game of academic musical chairs where the number of college applicants exceeded the seats that could accommodate them. The teenagers who entered the college admissions sweepstakes of the 1960s faced an anxiety level that would never fully be appreciated or duplicated by their descendants in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The number of applicants was growing faster than colleges were expanding to accommodate them, while the whole process of acceptance and rejection was played against the backdrop of military conscription and the Vietnam War.

For most postwar children the transition from high school to college began as they moved from tenth to eleventh grade. Junior year of high school was the time for the first formal prom, the training course that would lead to a coveted driver’s license, and the first career workshops offered by the school guidance staff. Eleventh grade also included one-on-one meetings with counselors who perused transcripts and often bluntly advised whether the child was indeed “college material.” Meanwhile “college nights” featured admissions personnel from a variety of schools who sometimes exhibited the smugness of individuals who knew their product was in greater demand than the supply could possibly accommodate.

As the juniors negotiated their way through a curriculum and grading system that had been made much more demanding in the wake of Sputnik, these early Boomers had their first encounter with the imposing bureaucracy of the CEEB, the College Entrance Examination Board. Sometime during the fall of their junior year, millions of teenagers took the PSAT, the Pre-Scholastic Aptitude Test that was a type of preview of the SAT, which was such a crucial factor in the college admissions process. Although counselors assured students that the PSAT did not “count” in any permanent sense, students and parents anxiously awaited the results and did the calculations that would turn the raw score into a rough preview of what might be expected in the “real thing” a few months later.

The closing months of the junior year usually brought the first encounter with the full-fledged “College Boards,” including the standard verbal and math examination and the aptitude tests that paralleled course subjects. These scores would usually arrive on a hot summer afternoon in the middle of school vacation, and the results—somewhere between the minimum of 200 and the maximum of 800—might prompt a family conference to help determine where, or if, an early Boomer would rise to the next level of education. On a group level the Boomers of the high school class of 1964 entered the testing season with enormous success. This class achieved the highest SAT scores of any group before or after, and would become the gold standard as scores gradually declined in future decades. Yet individually these children entered their final year of high school competing for college acceptance in a system that was simply not ready for them. Unlike their children, who would be asked by adults, “Where are you going to college?” the first Boomers would be asked, “Did any college accept you?” Senior year placed these teens in two worlds, a universe of the culminating activities and events of the high school experience, and another world of tense anticipation in which alternate plans were serious possibilities in case the response from every college was the dreaded thin envelope that contained the single sheet of paper signifying rejection.

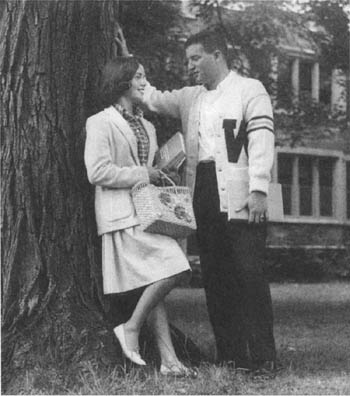

High school yearbooks of 1964 contain many features that would not look out of place in comparable annuals more than four decades later. Photos and commentary describe a breezy social whirl of homecoming dances, proms, and school plays. Successful athletic teams are held up as beacons of pride while even losing teams “played their hearts out” or gained “moral victories” in close losses. Candid classroom photos show popular teachers and eager students engaged in a more exciting learning process than most students remembered on most class days. A Who’s Who section pairs a boy and girl as “Best Dressed,” “Most Musical,” “Best Looking,” “Class Clowns,” “Most Popular,” or “Most Likely to Succeed.” Photos of social events hint at the ever-changing dating universe, where the couples at the fall homecoming dance may or may not be with the same partners at the senior prom.

The centerpiece of a high school yearbook, whether in the 1960s or the twenty-first century, is the section displaying all the graduating seniors, more formally dressed than on most ordinary school days. A litany of activities—Chorus 1, 2, 3, Football 3, 4, or Class President 4—hints at continuing and changing interests and the most popular or least active graduates. Beyond the changing fashion statements and the notes on activities, a difference in yearbooks several decades apart may be seen in the “future plans” under senior photos. A relatively typical twenty-first-century high school yearbook would list nearly three of four seniors intending to continue in school in a wide spectrum of institutions, from community colleges to world-class universities. But for about half the members of the first class of Boomer high school graduates, future plans would include specific jobs, marriage plans, military service, or vague assurances that a particular graduate “will be successful in anything he attempts” or have a “rewarding career in her chosen profession.” Many of these Boomers were in their last year of formal education, and more than a few would become parents in the very near future. Many of the cute couples in those yearbook photos were already pricing engagement rings.

The large number of Boomers for whom senior year in high school was probably their last school experience viewed twelfth grade from a different perspective. Many of these teens had found schoolwork a daunting combination of boring and difficult, and were tired of regimentation and bell schedules. They hoped their post-school careers would be more exciting and knew that work was more financially rewarding than school. Boys dreamed of buying their own car, girls thought about dramatically enhanced fashion choices, less encumbered by dress codes. For these students, the last game, the last dance, and the last prom carried greater nostalgia than the last class and the last exam.

The roughly equal number of Boomers who aspired to college viewed their senior year as a different transition. “College preparatory” courses in high school were already demanding, yet counselors, teachers, films, and books suggested that college would be even more daunting, with professors more stern and unyielding than high school teachers. College did offer the prospect of more choice of courses, less adult supervision, and a social life where fraternities, sororities, and related social activities were still a major and well-publicized part of the collegiate lifestyle. But senior year produced a number of decisions and complications. In the early sixties a boy was nearly twice as likely to attend college as a girl, and many high school couples wondered what would happen to their relationship if one went away to college while the other remained at home. Was the school close enough that the person staying home could visit on weekends? Would the student come home relatively often? Should either person be free to explore other relationships? Would an extended engagement be viable?

Boys contemplating college also had to include the prospect of compulsory military service in their plans. Should they enlist and enter college at a more mature age, enter a college ROTC program, seek a major that might secure a draft deferment, or take their chances on being drafted after graduation? Some of these options would be affected by the fact that while draft boards granted draft deferments for full-time students, anyone slipping below a C average for even a semester would be thrown into the draft eligibility pool. As the Vietnam War expanded and casualties rose, these decisions took on still greater importance.

In early June 1964 the oldest Boomers encountered their last round of high school examinations and attended commencement services that offered a bittersweet theme: a nation with seemingly unlimited economic potential, and the traumatic experience of John Kennedy’s death partway through the academic year. The New Frontier and Lyndon Johnson’s now emerging Great Society had produced generous pay raises, low rates of unemployment, and excellent job prospects for both high school and college graduates. Unlike their parents, this first cohort of Boomers boasted a near 90 percent graduation rate. During that summer at least some teens waiting to enter college must have experienced a twinge of envy for their peers who had already entered the workforce and were showing off their new cars, new clothes, and other short-term advantages over college.

The summer of 1964 emerged as a transitional period not only for the first Boomers but for American society as a whole. While many recent graduates inhabited that limbo between high school and college, the larger nation experienced urban riots, the murder of civil rights workers in the Deep South, a contentious Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, and an escalation of the simmering Vietnam conflict after the Gulf of Tonkin resolution in Congress. At a few schools, such as the University of California at Berkeley, a confrontational mood spilled over into the first full-fledged campus protest of the sixties, the Free Speech Movement led by Mario Savio. Yet in September new students arrived on the campuses of a nation that was generally upbeat about its future.

A lead feature in an early-autumn edition of one national magazine marveled at the prospects for American society. “An astonishing, unprecedented prosperity pervades the country. The GNP has risen $112 billion in three years. There aren’t enough pots to hold the chickens or enough garages to go around. Just as astonishing as the prospect is the way Americans take it for granted.”

As anxious and excited Boomers made tearful farewells to parents and siblings, an entire nation seemed vicariously to follow the exploits of the Spock babies who had now reached late adolescence. In some respects their college rituals would seem strikingly familiar to students inhabiting twenty-first-century universities. The endless trek with boxes and parcels from the spacious family car to a less than spacious dorm room; the initial exchanges between roommates who would now become major figures in one another’s lives; the alternately serious and silly rituals of freshman orientation; and the experience of sitting in a college lecture hall dominated by an erudite yet intimidating professor are hallmarks of both eras.

Beyond these commonalities, the collegiate world of 1964 would seem positively quaint nearly a half-century later. While the freshman world of 1964 would be seen as relatively casual compared to other generations of collegians, blazers and ties for men, skirts and dresses for women were still essential parts of a campus wardrobe. Students wearing flip-flops, shorts, and hooded sweatshirts would probably receive an invitation from the instructor to leave the classroom.

Residence life, that part of the “college experience” that now seems so important that counselors and parents encourage dormitory life for students who have a family home five miles from campus, was both less pervasive and yet far more regulated when the Boomers entered college. On the one hand, many urban institutions of the early sixties saw their mission as augmenting classroom space rather than dormitory space to meet the Boomer surge; in turn, many parents of college students who themselves had not attended college saw residence life as slightly absurd if their sons or daughters could easily take a subway, bus, or car to class and live free at home. Major urban universities, such as City College of New York, UCLA, the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, Villanova, and Loyola of Chicago, were typical city schools that concentrated on the instruction of large numbers of commuters, with dormitory space limited to students attending from long distances.

One of the realities of college life in 1964 that made commuters less inclined to envy their dormitory counterparts was that in many cases residence life was both more spartan and stricter than accommodations at home. American colleges had never been known for providing sumptuous housing, and since most sixties institutions were overcrowded, comfortable residence halls were often at a premium. Dormitories might include old structures beyond their prime, semi-permanent buildings slapped together to handle the G.I. Bill surge of veterans, and new facilities designed to hold maximum numbers of students. The combination of outdated or subpar electrical outlets and a general desire to discourage students from wasting time encouraged many colleges to forbid private television sets or telephones in rooms. Television viewing often became a communal experience as students sprawled around dormitory lounges where either the majority or the most vocal students determined choice of programs. Telephone use was often another form of communal enterprise as students queued to make calls as other residents hovered impatiently for their turn. Incoming calls largely depended on someone in the hall bothering to answer the phone or convey the message to the intended party.

If dormitories provided few choices for entertainment, dining halls offered equally few selections. A society in which few children were asked their preference for dinner at home was consistent in its attitude toward students “away at college.” Most meals offered one main course, though substitutions might be permitted. College dining services were also split between schools that allowed students to take multiple helpings and those that limited diners to one serving, forcing many students to rely on dorm snack machines for extra calories.

Communal phones and limited meal selections tended to be secondary concerns in the greater conflict between the individual and the university over the right of decisionmaking and autonomy. The first Boomers entered college at a time when the recent domination of university life by the “Silent Generation” of the 1950s had lulled administrators into a belief that the major crisis of the new decade would be swelling numbers, not serious student rebellion. In loco parentis was still taken quite seriously in the colleges of 1964 as student curfews and gender separation in residence facilities sometimes offered a student less freedom than he or she experienced at home. The relatively arbitrary rules and sanctions that permeated the college experience for the arriving postwar generation were particularly frustrating when they were linked to the daunting academic grind of the mid-sixties.

The demographic backdrop to the arrival of the Boomers was the stark reality that the 2.7 million college students of 1950 were now the 4.8 million of 1964, and that number was soaring with a baby boom that had not yet ended. A Yale freshman complained to an interviewer, “I feel like a mail-order bride as the work is poured on much faster than I expected and my teachers calmly refer to ‘those who stay in this course’; many of us are putting in 18-hour days to compete for a ‘C’ average.” Many very good high school students experienced their first taste of failure as reality came crashing down on them. More than a few teachers were encouraged by their superiors to grade on a strict curve, which guaranteed a substantial number of Ds and Fs. Some instructors graded more harshly, which could produce a class in which more than half of the enrolled students failed. This process produced a steady, barely subdued feeling of panic as students put in all the hours they could and still received grades that placed them on the brink of dismissal. Students agonized over the embarrassment of devolving from the high school “brain” to a dismissed college freshman returning home in disgrace. Even students with passable grades complained that on good nights they were able to sleep fewer than six hours while on some nights there was no sleep at all.

While Boomer college students of the mid-sixties began to challenge some traditions and rules, many aspects of the college experience were relatively slow to change. (Getty Images)

A Yale dean admitted that the high school class of 1964 faced “shattering pressure as their academic world tumbles down on them. They only accept it because they know everybody else is in the same boat.” Students frequently admitted to guilt feelings when they took even one night off from studying, and by the end of the fall term more than 20 percent required psychological counseling, even if they had escaped the dreaded letter of dismissal. Boomer students were thrust into a far more demanding environment than earlier collegians as colleges reluctantly accepted more students than they could possibly house or instruct and then employed a draconian grading policy to shrink the class to more manageable levels.

One of the results of this intellectual component to cold-war competition was a sense of uncertainty, anxiety, and fear of failure, from freshman student to college president. Media narratives and photographs of the period are filled with poignant images of dismissed students packing their books and saying goodbye to roommates while hurrying out of the dorm before the tears came. In other images, shocked and disbelieving parents usher their child toward the family station wagon, no doubt wondering how to tell friends and neighbors that their high school star has become a collegiate academic failure.

On a higher level, many of the Boomers’ professors found themselves caught between a rapidly escalating emphasis on publishing and a rapidly expanding pool of students who wanted instruction and advice. Even in an environment where colleges were hiring five new instructors for every faculty member who retired, professors still greatly feared a downward career spiral, in which failure to publish sufficiently might result in a move to a lesser school in “academic Siberia,” and poor student feedback might bring the same fate.

Finally, college presidents agonized over the approval of desperately needed expansion projects before financing had been completed, and raided other schools for faculty while attempting to foil raids against their own institutions. College executives who only a few years earlier had worried about smaller enrollments than expected now spent most of their waking hours dealing with the needs of a new generation whose numbers could barely be accommodated.

Even before Boomers were exposed to the social ferment of the campus of the late sixties, these students could see an era of change coming that would make their collegiate experience different from that of their older siblings. Yet the face of this change varied substantially across the range of the higher-education spectrum.

One of the most significant instructional developments in the period was directly related to the surge in student numbers. As colleges searched for new instructors to meet the growing need, graduate students were increasingly pressed into service as teaching fellows and teaching assistants. While many of them were young and energetic, they were also still students who had to manage their own assignments and examinations. Thus they often viewed their teaching duties as an imposition on their time. Also, a growing number of assistants and fellows in the sciences and mathematics were arriving in the United States from foreign nations with excellent minds but poor English-language skills, which made for torturous instruction in classes where concepts and facts were difficult to understand in perfect English. As class sizes grew and senior faculty avoided undergraduate classes in favor of research and doctoral seminars, more than a few students experienced the depersonalized atmosphere of huge lecture halls in which classes were taught by distracted, distant professors, with examinations graded by mechanical devices.

The gender makeup of classes was just beginning to change in a number of universities and colleges. Unlike early-twenty-first-century students who enter a higher education system where only 1 percent of institutions are open to a single gender, the Boomers entered college when nearly half of private schools were single-sex institutions and coeducation was still spotty and erratic at numerous public institutions. In 1964, for example, six of the eight Ivy League schools accepted only male undergraduates. The University of Pennsylvania featured coeducational classes with separately administered colleges for men and women, and only Cornell University accepted women with no restrictions. Outstanding female students who desired an Ivy education outside of Penn or Cornell could opt for “coordinate” women’s colleges such as Radcliffe (Harvard), Pembroke (Brown), or Barnard (Columbia), or attend other “Seven Sister” schools such as Mount Holyoke, Bryn Mawr, and Vassar. Prominent Catholic universities, such as Notre Dame, Georgetown, and Villanova, were either exclusively male or allowed women into only a handful of majors. Villanova enrolled five thousand men in its Arts, Sciences, Business, and Engineering colleges while two hundred women enrolled in the School of Nursing were allowed to enroll in English, history, and science courses limited to their gender. Even some state universities separated men and women whenever possible. While the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was open primarily to undergraduate males, females were expected to attend the Greensboro campus, which was essentially a women’s college. The state of Florida was in the process of making both the University of Florida, formerly a men’s school, and Florida State University, a women’s school, into coeducational institutions, with emphasis on the budding sports rivalry just beginning to develop at the two schools.

Students attending the majority of colleges that were coeducational by the mid-sixties discovered that differences in career goals continued to create classes that were dominated by one gender. Pennsylvania’s flagship state school, Penn State, featured extensive programs in agriculture, mining, engineering, and business, which produced a campus where males outnumbered females by more than two to one. On the other hand, the commonwealth’s fourteen “state teachers’ colleges” focused on elementary education, library science, and home economics, which guaranteed a heavily female student population. While girls were already beginning to dominate high school honor societies and honor rolls, they were entering college at a time when selecting a major outside traditional fields such as nursing, education, or home economics was still something of an adventure. Yet by 1964 the career “rules” were no longer etched in stone, and walls of gender separation were just beginning to crumble in school and workplace.

As gender roles changed, so did social relationships, even if that trend was not fully noticeable early in the Boomer college experience. Unlike the somewhat amorphous and shifting social patterns of twenty-first-century universities, where “hanging out” and “hooking up” carry different meanings for different situations, the first Boomers entered a college environment where most students were actively seeking opposite-sex partners and at least tacitly auditioning candidates for marriage and family formation.

Coeducational colleges offered numerous opportunities to form dating relationships through common classes, university or club social events, and joint social functions sponsored by men’s and women’s dormitories. At many schools fraternities and sororities were quite active. The 1970s film Animal House, which is set in 1962, offers a reasonable if exaggerated approximation of the fraternity system in place when the Boomers arrived at college.

While Greek organizations could be welcoming for students who successfully navigated the rush system, and provided a ready pool of potential boyfriends or girlfriends, there were generally not enough openings to accommodate all the students interested in auditioning for membership. Thus students on some campuses were forced into a potentially demeaning “independent” status, which forced them to craft a social life largely as outsiders, since the all-welcoming Delta House in the film was generally not an option on the real campus of the time.

The large minority of students attending single-sex colleges faced a more daunting task: attempting to meet appealing partners during a finite number of social encounters. Virtually every single-sex college sponsored “mixers,” in which bands, refreshments, and dancing attracted members of the opposite sex to come to the school for the evening. Even most rural colleges had a counterpart institution of the other gender within a reasonable distance, and, when necessary, buses could be dispatched to transport guests. One relatively remote New Jersey women’s college offered students from men’s schools free hors d’oeuvres, dinner in the college’s baronial dining hall, and a free admission to the dance to compensate visitors for the distance traveled. Men’s colleges in urban areas sponsored mixers that attracted not only female college students but similarly aged “working girls” who had entered careers after high school and often found the prospect of meeting a “college man” an exciting idea.

The mixer scene produced large numbers of budding relationships, but the somewhat forced, formal nature of the process could be less rewarding than the more informal relationships developed by lab partners or study group members in a coed school. And couples enrolled at two different schools could experience long periods without physical companionship and frequent phone calls on erratic dorm phone systems that offered little or no privacy. In some respects, Boomer students who attended single-sex schools in rural areas found their social lives lagging far behind those of high school classmates who had opted for the workaday world and were now developing relationships much more rapidly than their “luckier” college counterparts.

The Boomers who entered college and made the transition from secondary school to higher education without academic dismissal or major psychological trauma were now enrolled in institutions poised for massive change during their college careers. Since the end of Camelot in their senior year of high school, a new president, an expanding war in Vietnam, and new versions of social consciousness were pushing colleges and college students into an unexplored world of change and confrontation. Yet if this new Great Society produced unanticipated challenges, it also dramatically affected children’s lives in a wide range of ways, from enhanced educational opportunities to the exuberance of Beatlemania.