CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 2

Learning to Scavenge

The power given to the vulture by nature of discerning the approaching death of a wounded animal is truly remarkable. They will watch each movement of any individual thus assailed by misfortune and follow it with keen perseverance until the loss of life has rendered it their prey.

—John James Audubon, from Philosophical Journal, as quoted in

American Ornithology, edited by Alexander Wilson et al.

For a vulture investor there are, so to speak, many ways to skin a carcass. Over the years, I’ve tried a number of different approaches—some more successful than others—and enterprising vultures come up with new twists all the time. But a few fundamentals continue to apply.

Vulture investing is all about leverage. In today’s financial markets, the term leverage has come to mean the multiplication of risk by borrowing much more money than you put down in order to make an investment or buy a company. The idea is to increase your returns exponentially if the deal pays off. But, as the financial crisis of 2008–2009 has shown, that sort of leverage often leads to default and bankruptcy when things don’t go according to plan. So in that sense, leverage is a vulture’s meat and drink.

Leverage has another, more common, meaning, though: using a tool to gain power over people and events. Every lever has a fulcrum, the point or support on which it balances, and which enables it to move large objects with a relatively small force. To become a successful vulture, the most important talent you must develop is for swooping in on what we call the fulcrum security of any failing company in which you are considering an investment.

Technically, the fulcrum security is the one most likely to receive equity in the reorganized company after it goes through a Chapter 11 bankruptcy or another type of reorganization. This fulcrum can be a bond or a loan—it all depends on where the company is in the bankruptcy process when you invest, and how it has structured its capital and borrowings.

The more debt a distressed company has, the more likely it is that its reorganization will wipe out more-junior securities, such as stock, preferred stock, and subordinated bonds. The first security in the “waterfall,” the one that gets the largest portion of the newly issued equity, is the fulcrum.

But canny vultures won’t limit themselves to any one type of security. Before a company actually files for bankruptcy, the best opportunity can often be in shorting the stock. Of course, this is not as easy as it sounds. First you have to find companies on the skids, and find them early enough that the market hasn’t caught on yet. Then you must be able to trade enough shares to make the deal worthwhile. You also must master the technicalities: to short, you must find a counter party willing to lend you the shares at a reasonable rate.

When the wider market gets wind of a company’s troubles, the stock price will fall, giving you a substantial return when you buy it back much more cheaply, if you choose to do so. Other short-sellers may also pile in, however, pushing up costs for borrowing the stock, or making the stock so difficult to borrow that you can be caught in a squeeze.

Nonetheless, this strategy can often result in a 100 percent return if you short at the right time and have the stomach to wait until the stock is cancelled outright. What puzzles me is how many people refuse to believe that a company will fail, even after the signs of distress are very clear. For some investors, emotions take over; they won’t let go and realize their losses in the hope that somehow the company will muddle through and the stock price will eventually appreciate again. When that happens, it makes for a great shorting opportunity.

Over the years, I have shorted the stocks—or the deeply subordinated bonds—of many companies on their way into bankruptcy, including Lehman Brothers, General Motors (GM), Globalstar, Armstrong World Industries, Kmart, Pacific Ethanol, Northwest Airlines, US Air, United Airlines, Bear Stearns, Dynegy, Calpine, New Century Financial, and many others.

My short transactions in Globalstar Telecommunications were not only profitable, but also quite instructive, since they showed that it might take many quarters before the market finally realizes that a business is doomed to fail. The sole purpose of the publicly traded satellite communications company was to serve as the general partner for the operating company, Globalstar LP, a spin-off from Loral Space & Communications Inc., which retained a 39 percent ownership stake.

In spinning off Globalstar as a new business during 1999, Loral’s strategy was similar to that of Motorola, which did the same during the 1990s with Iridium, another satellite company that—like Globalstar—subsequently failed. Both Globalstar and Iridium aimed to launch global satellite networks that would provide the infrastructure for a new means of communication around the world. Although the plan was interesting in theory, the rapid growth of cellular phone service worldwide looked to make such a network redundant.

Even worse, both companies took on huge amounts of debt to start operations—in Globalstar’s case, more than $3 billion in junk bonds—instead of getting their funding from equity venture capital, as most startups do. Since the debt underwriting market at the time was white hot, it was perhaps easier for the parent companies, Motorola and Loral, to use debt financing for their spin-offs, but by doing so, they also ensured that they could sell billions of dollars in satellites to these companies without taking too much market risk themselves.

Globalstar intended to begin commercial services in September 1999. Unfortunately, getting off the ground (as it were) took longer than originally planned. Exhibit 2.1 shows Globalstar’s capital structure as of September 30, 2000. Note how debt, including funds payable to affiliates, amounts to over $3.2 billion, almost 1,000 times the paltry $3.7 million in revenues the company generated for the entire fiscal year.

EXHIBIT 2.1 Globalstar’s Capital Structure

| Capital as of September 2000 | Amount outstanding |

| ($ millions) | |

| Debt and other liabilities | |

| Bank term loans | $500.0 |

| Unsecured notes payable | $250.0 |

| Senior notes 11.375%, due 2004 | $500.0 |

| Senior notes 11.25%, due 2004 | $325.0 |

| Senior notes 10.75%, due 2004 | $325.0 |

| Senior notes 11.50%, due 2005 | $300.0 |

| Vendor financing liability | $304.0 |

| Qualcomm vendor financing | $515.5 |

| Other vendor financing | ($54.5) |

| Payable to affiliates | $231.7 |

| Trade claims | $11.5 |

| TOTAL DEBT | $3,208.1 |

| Equity | |

| Preferred | |

| Series A 8%, due 2011 | $220.0 |

| Liquidation preference $220m | |

| Shares (GTL) 4.4m | |

| Series B 9% | $150.0 |

| Liquidation preference $150m | |

| Shares 3m | |

| Ordinary partnership interest | $539.0 |

| Shares 61.922m | |

| Public equity | $0.0 |

| GTL, 35% | |

| Loral, 45% | |

| TOTAL EQUITY | $909.0 |

| Source: Company reports and Schultze Asset Management estimates | |

At that rate, Globalstar had no hope of covering its more than $300 million in interest expense, including accruals and required cash payments, for the same period. Bond investors were, in effect, gambling that Globalstar would be able to expand its revenues—by hundreds of millions of dollars—quickly enough to repay its borrowings. However, since most new businesses do not grow exactly as anticipated, financing them with huge amounts of leverage usually doesn’t work too well.

By the end of 2000, Globalstar was floundering, with an annual interest expense almost 100 times its revenues. In mid-January 2001, the company announced that it would indefinitely suspend interest and principal payments on its debts.

Although it was obvious from the outset that the business was unlikely to succeed, shorting Globalstar stock was not as easy as you would expect. After an initial offering in the low $20s, the company’s stock appreciated into the mid-$40 range before finally crashing back to earth when the company went out of business. At one point, despite its terrible prospects, the company—incredibly—announced that it had hired Bear Stearns to help it manage a secondary equity offering, prompting a more than $10-per-share jump in the existing stock.

Bear, which vanished in the 2008 credit crisis due to its own excessive leverage, clearly managed to find ways to pump up demand for this soon-to-be worthless secondary stock offering. These (perhaps questionable) tactics delayed the inevitable for a few months longer than we expected, but we still earned a nearly 100 percent return shorting Globalstar stock. In addition, we did well shorting Globalstar’s unsecured bonds after the company filed for bankruptcy.

Iridium’s story is much the same: Exhibit 2.2 shows the company’s capital position in October 1999, two months after it filed for bankruptcy. Like Globalstar, Iridium had a huge amount of debt and other liabilities (almost $4 billion) while its revenues were tiny.

EXHIBIT 2.2 Iridium’s Capital Structure

| Capital as of October 1999 | Amount Outstanding |

| ($ millions) | |

| Debt and other liabilities | |

| Secured bank facility | $800.0 |

| Post-petition amounts owed to Motorola | $118.2 |

| Motorola-guaranteed bank facility | $740.0 |

| Senior notes, series A (13%, due 7/15/05) | $300.0 |

| Senior notes, series B (14%, due 7/15/05) | $500.0 |

| Senior notes, series C (11.25%, due 7/15/05) | $300.0 |

| Senior notes, series D (10.875%, due 7/15/05) | $350.0 |

| Debt to members (14.5% senior subordinated notes, due 2006) | $568.9 |

| NASA claims | $60.0 |

| Interest payable (pre-petition, bonds, and bank) | $106.8 |

| Pre-petition accrued liabilities | $3.5 |

| Capitalized leases | $43.3 |

| Trade claims | $12.8 |

| TOTAL | $3,903.5 |

| Equity | |

| Preferred stock | |

| Liquidation preference | $46.0 |

| Shares 0.048m | |

| Common stock (Iridium LLC) | ($952.70) |

| Shares 150m | |

| 19.7m publicly held | |

| 130.3m non-tradable interests (Motorola, other strategic investors) | |

| TOTAL (book value) | ($906.7) |

| Source: Company reports and Schultze Asset Management estimates | |

For the 12 months ending March 31, 1999, Iridium had generated only $1.7 million in revenues, while interest expense for the same period amounted to $181.3 million.

More recently, our short on Dynegy Inc. stock has proved an interesting opportunity for us as well. Dynegy, one of the largest independent power producers in the United States, owns and operates natural gas-fired and coal-fired power plants and sells electric energy and capacity as a wholesaler.

Dynegy’s subsidiary, Dynegy Holdings, became one of the highest profile bankruptcy cases of 2011. At the time of writing, it remains in Chapter 11, and although the parent company avoided filing for several months through some crafty (and I believe, possibly illegal) dealings, in July 2012, it joined its subsidiary in Chapter 11.

Dynegy’s saga has been long and eventful. Already struggling by late 2010, as its market conditions in the power production industry deteriorated, Dynegy hoped to solve its problems through a buyout. But shareholders rejected offers from the Blackstone Group, and later from activist investor Carl Icahn, who nonetheless became one of its largest stockholders. I had worked with the Icahn team over the years, usually on the same side, so I was surprised and dismayed by subsequent developments.

Icahn’s first move was to put his right-hand man, Vincent Intrieri, a senior managing director at Icahn Enterprises, on the board. During the Tropicana Casinos bankruptcy in 2009, I’d gotten to know the shrewd but volatile Intrieri, whose profane outbursts during tension-filled negotiations became legendary. Shortly after Intrieri joined the board, it appointed a financing and restructuring committee and made Intrieri its chair.

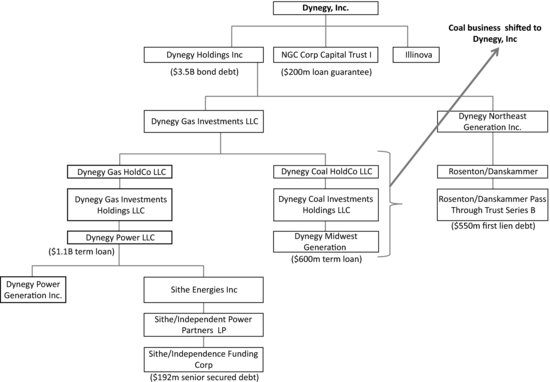

At that time, the public company, Dynegy Inc., owned the operating company, Dynegy Holdings. The restructuring committee quickly reshuffled the management team and created two so-called “silo” subsidiaries beneath Dynegy Holdings: one producing coal and one producing natural gas.

To avoid an imminent default, it refinanced the company’s $918 million in senior secured loans, tacking on an additional $650 million to those loans. At that point, Dynegy Holdings also had $3.3 billion in unsecured debt and $200 million of subordinated debt outstanding, plus $550 million in guarantees on its existing leases.

Intrieri’s restructuring committee then orchestrated a complex transaction that essentially shifted the coal company, Dynegy Holdings’ best-performing asset, into the direct possession of Dynegy Inc., the public company in which Icahn held stock. In this deal, the public company bought the coal subsidiary from Dynegy Holdings in exchange for an unusual and illiquid instrument it called an “undertaking,” to which the board assigned a value of $1.25 billion. Exhibit 2.3 shows an organization chart for Dynegy before this transaction.

EXHIBIT 2.3 Dynegy Organization Chart

This instrument had no covenants to protect the holders from any later company actions that might affect this supposed value. I considered the whole transaction highly questionable, and I wasn’t the only one.

Since the natural gas company wasn’t doing very well, Dynegy Holdings no longer had the earnings to support its debt, and subsequently filed for Chapter 11, leaving Dynegy Inc. with a fairly profitable coal company and a bankrupt subsidiary. The Dynegy Holdings filing proposed a plan of reorganization that seemed designed chiefly to give Dynegy Inc. some breathing room to overcome its financial and operating challenges.

But the proposed plan did little to help Dynegy Holdings itself, leaving the reorganized company still too highly leveraged, with a net debt of more than eight times its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization; that is, 8.0×net debt/EBITDA. (Comparable companies average 4.0×net debt/EBITDA.) Moreover, the plan included provisions that would have given 97 percent of the equity to creditors if the company didn’t pay off $2.1 billion in preferred stock by 2015. Although this didn’t really present a major problem, these provisions made it all too clear that that the overleveraged company was really being set up to fail again.

After subordinated bondholders raised objections to both the plan’s structure and to its intent, the bankruptcy court appointed an independent examiner to review everything Dynegy had done during the months leading up to the filing. I was pleased at this development, particularly since I had worked with the examiner, Susheel Kirpalani, some years previously on the Levitz Furniture bankruptcy.

Kirpalani, a partner at a New York law firm, Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP, released a 50-page report on March 9, 2012, concluding that the questionable transaction was, in fact, a “fraudulent transfer” and that the reorganization plan was unfeasible.

The report boosted prospects for short investors in Dynegy Inc. stock especially after the court subsequently rejected both the transfer and the plan. My firm took a short position early on, selling at nearly $6.00 per share in April 2011. The stock drifted steadily downwards over the next year, but when the report came out, Dynegy’s share price dropped 50 percent in one day.

Exhibit 2.4 shows Dynegy’s precipitous stock price fall over a nine-month period, from over $6.00 per share to less than 50 cents shortly after the examiner’s report was released. I began shorting the unsecured bonds as well, and currently expect to see a good profit on that position as well.

Probably my most profitable short trade was in the common stock of Northwest Airlines, which I put on after the company had already filed for bankruptcy in September 2005. I made a lot on this bet in absolute terms, partly because of its size; professionals at my firm’s prime broker (UBS Prime Brokerage) told me that our position in Northwest Airlines stock was the largest short on its books at the time.

As with most airlines during the last several years, Northwest Airlines became hopelessly insolvent as too much debt, legacy liabilities, volatile fuel costs, and intense competition overwhelmed it. The growth of the Internet compounded Northwest’s problems by giving customers more bargaining power. I got a great return from shorting Northwest stock because it was so high before it collapsed to nothing.

Exhibit 2.5 shows the Northwest Airlines capital structure as of October 31, 2006—about a year after its September 2005 bankruptcy filing—with liabilities of more than $10 billion. For the 12 months ending September 30, 2006, Northwest had generated $606 million in EBITDA (after deducting capital expenditures), which barely covered the company’s more than $500 million in interest expense. Considering that it had debt amortization payments coming due shortly, its position was clearly unsustainable.

EXHIBIT 2.5 Northwest Airlines’ capital structure

| Capital as of October 2006 | Amount Outstanding |

| ($ millions) | |

| Debt and other liabilities | |

| Debt not subject to compromise: | |

| DIP Facility | $1,294.0 |

| EETCs due through 2012, 9.8% average interest | $182.0 |

| Secured loans due through 2025, 7.5% avg int | $671.0 |

| Other secured debt through 2031, 4.5% avg int | $1,027.0 |

| Professional fees due | $12.1 |

| Secured pre-petition claims: | |

| EETCs due through 20’22, 6% int | $1,987.0 |

| Secured loans due through 2023, 3.6% int | $2,156.0 |

| Capital leases | $238.0 |

| Unsecured pre-petition claims: | |

| Unsecured notes due 2004-2039, 8.7% int | $1,313.0 |

| Other | ($239.0) |

| Convertible unsecured notes due 2010, 6.625% int | $375.0 |

| Accounts payable | $1,888.0 |

| Pension and employee benefits | $4,066.0 |

| Aircraft accruals and deferrals | $2,863.0 |

| TOTAL | $17,833.1 |

| Equity | |

| Preferred: | |

| 9.5% due 8/15/2039 | $278.0 |

| Shares 5.7m | |

| Common stock | ($7,958.0) |

| Shares 87.3m | |

| TOTAL | ($7,680.0) |

| Source: Company reports and Schultze Asset Management estimates | |

Bizarrely, Northwest stock began to appreciate sharply after the company’s creditors had voted on its plan of reorganization, which specified that equity holders would get nothing. The company’s 10-K and 10-Q filings confirmed that the stock would almost certainly be cancelled altogether.

Nonetheless, a short squeeze, (short supply and excess demand) temporarily pushed the stock price up dramatically, from less than $2 per share to over $6. During this time, there was also speculation and hope that another airline might acquire Northwest, thereby saving the stock. This line of thinking made no sense, since a buyer wouldn’t have to pay anything to Northwest stockholders (as is true for nearly every bankrupt company) because creditors obviously owned the fulcrum security.

This was a great development for me, creating an even better short opportunity by allowing me to substantially add to our firm’s position in Northwest common shares at nosebleed levels. A few months later, the common stock finally fell below 25 cents per share before it was cancelled entirely, resulting in a 100 percent profit.

Normally, once a company has begun to fail, shorting the stock may no longer be your best bet. If it has already gone down substantially, potential remaining profits from shorting diminish—you might even take a loss just from the continued cost of borrowing the stock for the uncovered short. At that point, you should be looking at the troubled company’s debt for your fulcrum.

Companies issue debt in many forms: short-term commercial paper, medium-term notes, secured and unsecured long-term bonds, asset-backed securities, and bank loans. Generally, the fulcrum security is the most senior, since its holders will be paid first if the company’s remaining assets are sold during bankruptcy reorganization, or they will get the most stock if the result is a debt-to-equity conversion.

When you buy a company’s debt, sometimes your aim is to get it at a significant discount to its full face value (par), which in some cases can be pennies on the dollar. You may then reap a good return when the bankrupt company pays off its creditors, preferably at par—or at least at a smaller discount than you got in the open market.

You could also sell the debt for a quick profit if the value increases in anticipation of a bankruptcy, especially if the market believes the company has some worthwhile assets to realize. In other instances, you may want to convert that debt into equity in the post-bankruptcy, reorganized company.

In the past, the fulcrum was most likely to be a company’s senior secured bonds, which were at or near the top of its capital structure. But things changed when a liquid secondary market in syndicated bank loans, particularly in leveraged loans, developed in the early 2000s. Leveraged loans are the equivalent of junk bonds—higher interest, riskier lending to less-creditworthy companies. Since this new secondary market created an easy way to sell these loans, banks and investment banks began making more of them, often on better terms than companies could get in the public bond markets.

As often happens on Wall Street, investment bankers started looking for more ways to generate fee income from the new market, chiefly by creating investment vehicles to buy the paper they themselves issued. Lehman Brothers, Goldman Sachs, Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Bank of America, and Citigroup all created so-called structured credit funds to invest in leveraged loans.

The leveraged loan market’s development paralleled that for securitized mortgages, which turned the housing sector into a casino—before its spectacular blowup. In 2007 and 2008, leveraged loans crashed along with other forms of risky debt, leaving investors in structured credit funds with terrible losses, and contributing to the spread of the global credit crisis.

Nonetheless, the massive supply of new senior secured bank loan paper is more often than not the fulcrum security these days. This is because it often gets the biggest payout in a bankruptcy, whether in cash, new debt, or new equity. The rise of the loan market, however, has also increased the power that banks wield in bankruptcy proceedings.

As the most senior lenders with the highest priority, banks have the most security and generally band together in a committee to further their interests during the bankruptcy. Since their business is lending to companies, not owning them, banks mostly want cash, not stock.

In fact, it isn’t legal for U.S. banks to have more than a small percentage of their balance sheets tied up in equities.1 Moreover, new banking guidelines have further reduced the permitted equity percentage of a bank’s balance sheet. These regulations include the international Basel III agreement (nearly all of which the United States agreed to implement in December 2011), as well as the U.S. Volcker Rule, a part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act signed into law in July 2010.

For a vulture, getting a higher cash payout is great, but the real money is in the post-bankruptcy equity. Why, you may ask, would anyone want to own stock in a bankrupt company? The shares are unlikely to be worth much, and they may not trade on one of the major exchanges, at least at first, or even have a market maker for over-the-counter trading.

Wall Street analysts probably won’t cover the stock either, partly because of the bad blood that a bankruptcy often leaves in its wake. Analysts who had recommended the stock before the company’s fall from grace may feel stupid and burned. Some may even have lost their jobs because they maintained their “buy” ratings on the stock even as it fell to zero, wiping out investors.

But vultures see tremendous upside potential in post-reorganization stocks. After Chapter 11 reorganization, the company has most likely walked away with little or no outstanding debt, and sometimes may pay no corporate income tax for many years, if it has been able to preserve “carry forward” tax deductions for its pre-bankruptcy net operating losses (NOLs).2

Moreover, partly because banks usually are forced to sell equity they get in bankruptcy, these stocks often trade initially at a huge discount to fair value. While industry peers trade at more than six times annual cash flow, for example, the post-bankruptcy shares might cost as little as one or two times cash flow.

Some vulture investors, even if they didn’t get equity in the bankruptcy, will buy shares in the newly reorganized company at this point. Vultures willing to roll up their sleeves and do their own analysis can pick up great bargains in the post-bankruptcy bin. Either way, patience is likely to pay off handsomely if you can find opportunities while banks and other owners who need to offload the stock are still holding down the price. Once these forced sellers have finished divesting and some time has passed, these stocks often find their way back to more normal valuations.

Eventually, people begin to figure out that the company is worth something: sell-side analyst coverage resumes and the valuation gap starts to narrow. Or perhaps an acquirer, either strategic or financial, comes along and pays a premium for the shares. The current management might even make a bid to buy out the company. Of course, not every opportunity works out well, so maintaining portfolio risk controls and diversification is critical for success.

My investments in Algoma Steel, a Canadian steel producer (now Essar Steel Algoma), and Washington Group, a U.S. engineering and construction company, are two good examples of how buying the fulcrum security at the right time can work for a vulture. With Algoma, I bought the fulcrum security shortly after it emerged from reorganization and then employed an activist approach to help create value. With Washington Group, I got involved earlier, investing in the fulcrum security both during and after the company’s reorganization.

In the early 2000s, most steel companies in North America had several bad years as prices fell on the world market and the dollar’s exchange rate rose to exceptional heights—along with costs for input commodities like coal and electricity. This perfect storm wreaked destruction throughout the steel sector, but highly leveraged companies and those with extensive legacy liabilities (like underfunded pensions or healthcare obligations) were the first to go.

Steel companies that took on too much debt during the boom were forced into bankruptcy. This long list included LTV Steel, Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel, Algoma Steel, Keystone Consolidated, Republic Engineered Products, WCI Steel, Weirton Steel, Bayou Steel, Birmingham Steel, National Steel, Sheffield Steel, Metals USA, Bethlehem Steel, Freedom Forge Corporation, Republic Technologies, Trico Steel, Geneva Steel, and Acme Metals, among others.

Algoma Steel, a company with more than 100 years of operating history, was then North America’s third-largest integrated steel manufacturer, accounting for 14 percent of Canadian steel production. In February 2002, the company emerged from its second round of restructuring under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA), the Canadian equivalent of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Under its CCAA plan, Algoma management had reduced debt so much that, by the time we started looking at the company in 2004 and 2005, it was starting to distribute capital back to shareholders.

In a successful reorganization, the new company that emerges from restructuring generally has little or no remaining debt outstanding and the former senior creditors as its major shareholders. But many of these former creditors must sell their shares, regardless of the business fundamentals. In addition to banks, likely forced sellers include retail bond mutual funds, which generally have portfolio constraints precluding them from holding the new stock.

Predictably, most of Algoma’s old creditors rushed to liquidate their post-reorganization stockholdings, despite the potential upside. Through the 12 months ending May 2005, the company’s public stock ranged from a low of C$3.70 per share to as high as C$29.60.

Even at that price, however, the stock was trading at a low multiple of its cash flow. Its total enterprise value (TEV) of C$748 million was only 1.06 times its trailing 12-month EBITDA of C$695 million. (I calculated the TEV by adding the company’s $1.2 billion in equity market capitalization to its C$151 million in 11 percent senior secured notes, then subtracting the C$602 million in cash on its balance sheet.)

When I began buying Algoma’s post-reorganization equity in November 2004, I found myself competing with another vulture investor, John Paulson. Since Algoma’s board had paid down all of the company’s remaining debt during its reorganization, its healthy earnings had enabled it to accumulate several hundred million dollars in excess cash.

That financial flexibility had allowed the board to take steps to raise its stock price, distributing a special dividend to shareholders of C$6.00 per share in August 2005 and buying back stock. It had also announced an extensive strategic review and considered a number of alternatives for the company, including making acquisitions, distributing more cash to shareholders, and the sale of the entire company.

In March 2006, after negotiations with Algoma’s management, Paulson got the company to agree to distribute C$200 million to shareholders while continuing to explore strategic alternatives to maximize shareholder value. But a few months later Paulson had become fed up with the slow pace and sold his shares—most likely, right after the company declared the special dividends.

I decided to stick with the stock. Algoma’s next move was a new substantial issuer bid, an offer to buy back up to 3.2 million shares (representing 10 percent of the company’s share float) over the following 12 months.

Even after those measures, by the end of 2006, Algoma’s valuation was still unreasonably low. The company’s balance sheet as of September 30, 2006, included no debt at all and more than C$200 million in cash. Net of this cash, the company’s market capitalization amounted to C$830.4 million by January 3, 2007, which was only 1.9 times its trailing (September 30) EBITDA of C$435 million. By contrast, the average multiple for other publicly traded steel companies was 5.50.

Moreover, during a November 2006 teleconference, Algoma management suggested that its EBITDA was likely to increase, detailing a plan to reduce costs by C$130 million over the following three years. For me, the company was simply too cheap to ignore.

During a visit to Algoma’s management and its facility in Canada, I discovered that its direct strip production complex, which was running at 100 percent capacity, was the lowest cost producer in North America. I also found out that Algoma owned a 10 percent royalty interest in a Canadian diamond mine, as well as thousands of acres of real estate surrounding its main operating plant.

Since management had been unsuccessful at boosting shareholder value by conventional means, I concluded that the best way for Schultze Asset Management to realize gains from our investment was to bid to buy the business. I reckoned that if Algoma’s board agreed to the buyout, we could use debt financing to get the company for nothing. If the board refused, the move would nonetheless put Algoma into play, giving us a good return when another buyer paid a premium for the shares we already owned.

As expected, Algoma’s board rejected our bid out of hand, but it did agree to negotiate with us. These negotiations went on for several months as we ratcheted up our offer. Eventually, our backup strategy succeeded as other bidders started to surface, including India’s Essar Steel. A string of legal cases (most notably, Ron Perelman’s suit against Revlon, which gave him control) has established that once a U.S. company is clearly on the block, corporate directors have a fiduciary duty to explore fully all legitimate buyout bids to achieve the best value for shareholders.

We lost the bidding war to Essar, but we profited handsomely from its acquisition of Algoma for C$56 in cash per share. Even though that price represented a nice premium to my average purchase price for the stock (less than C$20), I was sad to see Algoma go for a relatively low valuation. Essar got the company for 4.02× its trailing EBITDA, which, although nearly three times its prior trading price, was still below the average industry multiple.

Washington Group International (WGI) is another interesting example of a successful fulcrum security investment, but in two different fulcrums—one I bought into during the reorganization, and one afterward. I started looking at the company in earnest in 2001, as it approached bankruptcy. WGI was an enormous company that offered design, construction, and engineering services for projects such as highways, roads, bridges, power plants, manufacturing facilities, and even railroads. One of its best-known projects was the massive Hoover Dam.

In a previous incarnation as Morrison Knudsen Corporation, the company had also gone through a period of distress, including a 1996 bankruptcy, during which industrialist Dennis Washington’s Washington Construction Group bought it for $221 million. So, when WGI filed for Chapter 11 in May 2001, it was a second round—a “Chapter 22” filing, one might call it. In both cases, the main culprit was too much borrowing.

When it went into bankruptcy, WGI owed $300 million on an 11 percent senior bond issue, about $572 million in loans outstanding on its $1 billion credit facility, and about $540 million in other liabilities, which included trade payables, accrued salaries and wages, taxes payable, postretirement benefits, accrued workers’ compensation benefits, and environmental liabilities. By the end of 2001, it had added a $200 million debtor-in-possession (DIP) loan—a special facility that lenders extend to companies in Chapter 11—bringing its total liabilities to about $1.4 billion.

Unfortunately, as its liabilities grew, WGI’s cash flow shrank. Although WGI generated $3.2 billion in revenues during 2000, its EBITDA for that year was only $2.9 million, while it paid $38.4 million in interest expense. Like many companies that get into trouble, WGI’s troubles began with an unwise acquisition, financed by massive debt. In July 2000, it paid $53 million in cash and assumed an estimated $450 million in debt to purchase Raytheon’s engineering and construction (RE&C) unit. Credit Suisse, which had just finalized WGI’s $300 million bond offering in June, extended a $1 billion senior loan facility to WGI to finance the purchase.

Under the purchase arrangement, Raytheon executives were required to submit audited balance sheets to WGI within 60 days of closing, at which time the final acquisition price would be adjusted. But Raytheon never produced these audited statements, and it became clear after closing that it never would, since Raytheon executives had apparently fudged the numbers.

According to WGI, RE&C’s actual liabilities totaled over $700 million, a figure far greater than Raytheon had claimed in the deal disclosure statements. RE&C’s true profits were much lower, and its costs much higher for the infrastructure project contracts that WGI had assumed in the deal.

When WGI realized the true state of affairs, it halted all work on two major contracts it had inherited from Raytheon in the RE&C acquisition. Under the purchase agreement between the two companies, this action required Raytheon to finish the work at a cost of $325 million. Naturally, they wound up in court, with each side claiming the other owed it hundreds of millions of dollars.

WGI sued Raytheon, charging it with fraud and seeking a $400 million refund from the purchase transaction. In the meantime, Raytheon denied any impropriety, arguing that WGI had carefully scrutinized RE&C and its books for many months before finalizing the deal. Regardless of who was to blame, WGI had racked up far too much debt to fund the acquisition, and didn’t have nearly enough cash flow to support it. In May 2001, WGI missed its scheduled bond interest payment and declared bankruptcy.

At that juncture, Dennis Washington still owned 38.7 percent of WGI shares. Since the company largely depended on Washington’s industry contacts to attract new infrastructure contracts, his threat to leave persuaded WGI’s lenders to give him favorable terms under the proposed reorganization plan. This initial plan allowed Washington to purchase 15 to 40 percent of the new company’s shares.

But a committee of unsecured creditors challenged the plan—which gave them little or nothing—maintaining that it was too generous to Washington and other insiders. After many tumultuous negotiation sessions, all the parties, including Dennis Washington, reached a compromise, settling the Raytheon dispute in the process. At this point, I determined it made good sense to get into WGI securities and bought some of the company’s senior secured loans. WGI emerged from the reorganization proceedings on January 5, 2002 under a revised plan.

From my point of view, the reorganization was a success, since it left WGI with practically no debt. Moreover, the settlement forced Raytheon to take back several hundred million dollars in construction and environmental liabilities—a highly favorable outcome for WGI, even though no cash changed hands.

Unsecured creditors got 20 percent of WGI’s newly issued stock, plus warrants for future stock purchases. The senior lenders in my class proved to have the real fulcrum security, getting 80 percent of the new stock (subject to dilution from management incentive shares and the unsecured creditor warrants) plus $20 million in cash.

The unsecured creditor warrants, issued in three tranches, ended up as a better deal than they first appeared. Each tranche gave the holders the right to buy 10 percent of the stock when WGI reached a specified TEV: the first at $725 million, the second at $825 million, and the third at $888 million. Since the company’s TEV was around $360 million when these warrants were first issued, they were too far “out of the money” to have much cash value, but they eventually became worth much more.

Despite the company’s improved position, WGI’s stock price remained in the mid-teens, and more than a year later, in early May 2003, it had only risen to $19.50 per share—a $487.5 million capitalization based on 25 million fully diluted shares outstanding.

Since WGI was debt-free and had about $127 million in cash on its latest balance sheet, this price translated into a TEV of just 2.3 times its trailing 12-month EBITDA of $154 million, less than a quarter of its $1.8 billion total capitalization before the bankruptcy. This multiple was ludicrously cheap compared with its peer-group average of around six times EBITDA.

However, investors remained largely uninterested in the WGI story. The original lenders, chiefly banks unable to hold the stock long-term, had naturally sold out early on. Other pre-petition lenders suffered from deal fatigue after their substantial losses and all the litigation uncertainty. Meanwhile, since the stock market was still suffering the aftereffects of the 2000 Internet bust, no one wanted to take any risk, particularly with an infrastructure development business that had failed twice before.

Despite this lack of overall market interest, I couldn’t stop thinking about WGI—and apparently, neither could some of our competitors. David Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital eventually amassed a 10 percent stake, Jeffrey Gendell, a hedge fund manager, bought around 7 percent of the stock, and my old shop, M.D. Sass, ended up with 5 percent. My stake was a bit under 2 percent.

By December 2005, I was still an investor in WGI stock, but I had become frustrated with the investment’s lack of progress and sensed that other investors were frustrated too. The stock was still in the dumps, even though the company was firing on all cylinders; WGI was now listed on Nasdaq, and it had 150 major projects underway, plus a 400-project backlog worth almost $5 billion, including highly lucrative contracts in Iraq.

Although the stock had risen to $51.75, management’s projected full-year results for 2005 put WGI’s TEV/EBITDA at 5.30×, less than half its average peer-group valuation multiple of 12.49. WGI still had no debt outstanding, plus about $300 million in cash on its balance sheet. In addition, WGI had carried forward a $169 million net operating loss (NOL) for tax purposes, which meant that it would avoid paying out cash in taxes for several years to come. The company was therefore in a much better position than most of its rivals.

I decided I needed to mount an activist campaign, so I hired a bulldog law firm to help me. I first took on the company over the warrants for stock purchases issued to unsecured creditors, which were about to expire. WGI was trying to buy these warrants back, at just a fraction of their fair value, from the creditor trust that held WGI stock and warrants to be distributed once the final claims pool was settled.

If I had remained passive, management’s plan would have ultimately hurt my interests, since by that time I owned WGI unsecured bonds with a face amount of more than $300 million. These bonds were among the largest beneficial owners of the creditor trust.3

My firm decided to help level the playing field by suing WGI over this unfair treatment to creditors and by outbidding the company for the warrants in Nevada’s bankruptcy court. Other creditors, including M.D. Sass, Third Point Management, Dalton Investments, and Whitebox Advisors, all joined our campaign. Although we ultimately lost the auction, we did succeed in getting WGI to bump up its bid to buy the warrants by many millions of dollars. As a result, the trust beneficiaries, including bondholders, saw a substantial victory.

While my campaign over the stock warrants in the creditor trust only tangentially addressed WGI’s languishing stock price, my next move tackled it directly. In July 2006, we sent a letter and presentation to WGI’s management and board making a convincing case that the company’s stock was undervalued by nearly $50 per share. We also outlined a series of practical steps, including over $740 million in stock repurchases, which the company could take to increase shareholder value.

Since our firm owned less than 2 percent of the stock, I admit I was a little surprised at how seriously management and the board took our proposal. But it later became apparent that WGI’s management and board had long shared my frustration. To boost shareholder value, the board had already started a $100 million stock buyback and had even hired an investment bank to help it explore strategic initiatives.

Within a few weeks, the CEO came to visit our offices in Purchase, New York, to talk about our plan, and the board engaged Goldman Sachs to review the merits of our proposal. I was invited to the company’s next shareholder meeting to present our plan, which management had added to the company’s annual shareholder proxy.

I showed up for the meeting and pontificated for a while about increasing shareholder value more quickly. I didn’t know, however, that the board was already negotiating to sell the company. In May 2007, WGI announced a merger with URS Corporation, an engineering, design, and construction firm, which agreed to buy all the outstanding equity for more than $$100 per share in cash and stock. Since we had begun buying the fulcrum securities just a few years before, when prices were in the teens, this was an extremely satisfying result.

As all these examples show, it’s no easy task to find the perfect balancing point to maximize your power while you minimize your investment. You need to buy the right security at the right time for the right price—and then stick with it as long as necessary.

A vulture might go a long way on instinct alone, but thorough research, constant monitoring, and real persistence are much more important. You can’t fall asleep on your perch—you must be up in the air, scanning your territory with a keen eye for prey.

1The U.S. Bank Holding Company Act contains these limits.

2Net operating loss carry forwards are referred to by tax practitioners as NOLs and are generally covered by Section 386 of the Internal Revenue Code, which governs the transferability of NOLs and sets annual limits on their usage.

3Under WGI’s Plan of Reorganization, a creditor trust was established to hold WGI stock and warrants that belonged to unsecured creditors. Due to the complexity of the WGI case, it took the trust attorneys several years to sort out duplicate or inaccurate claims, which included many that Raytheon had assumed. The court finally allowed under $1 billion in claims, although unsecured creditors initially had filed for over $4 billion.