| 1 | JAFFA AND TEL AVIV |

Sunday, August 25, 1929

We will open with an account of what happened in Tel Aviv, Acre, and Jaffa in 1929 because these cities were on the margins of the disturbances. We will learn of the triangle of relations between Mizrahi Jews, Ashkenazi Jews, and Arabs and the way these relations were shaken, and we will meet, among others, Mustafa al-Dabbagh, Yosef Haim Brenner, Simha Hinkis, Nisim Elkayam, and Ahmad al-Shuqayri. One thing leads to another, and one person leads to another.

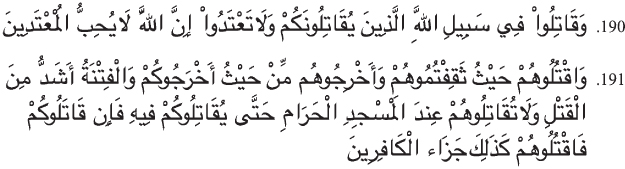

In the summer of 1929 the Jews provoked the Muslims: thousands of their young and old people gathered on the streets of Jerusalem with the Zionist flag, adorned with black ribbons, waving over their heads. They marched in an organized fashion to the Western Wall—al-Buraq—enthusiastically singing the Zionist anthem, “Hatikvah.” Their voices rang out: “The Western Wall is ours, beware all who sully our holy site.” It was this provocation that led to the clashes that spread through the country in August 1929.

In Jaffa Jews, led by a Jewish policeman in the government service, attacked the home of Sheikh ‘Abd al-Ghani ‘Awn, the imam of the Abu Kabir neighborhood mosque, next to Tel Aviv. They killed him and all six members of his family and defiled the bodies criminally. They slashed open the father’s belly and smashed the heads of his nephew and his wife and son, who was three years old at the time. (Dabbagh 2002, 4:265)

This description appears in the volume on Jaffa and its environs, of the ten-volume work titled Biladuna Filastin (Our land of Palestine) by Mustafa Murad al-Dabbagh (2002). It is not a work of history but rather a geographical encyclopedia, arranged by region. Neither does it offer in-depth analysis. Rather, it surveys all the cities and villages of Palestine, noting significant events that took place in each one. An important reference work, it is frequently consulted by readers of Arabic. Given its nature, it does not offer a comprehensive survey of the events of 1929. Yet it cites a significant event—unfamiliar to Israeli and foreign readers as well as to many Arabs—the murder of an Arab family and the mutilation of their bodies by Jews.

The picture is a harsh one. It is not easy to read about the smashing of children’s skulls, the mutilation of bodies, and the slitting open of bellies. Furthermore, what connection is there between the riots of 1929 and the slaying of an Arab family by Jews? After all, the theme of the events of 1929—at least as far as Jews are concerned—is Arab brutality. But this is what al-Dabbagh tells us about what happened in Jaffa and Tel Aviv in 1929. In short order we will examine the truth of the story, but in any case it is important to keep in mind that it was not the start of the 1929 riots.

Not the Start

The 1929 riots officially started not in Jaffa but in Jerusalem, two days earlier, on Friday, August 23. The climax came the following day, Saturday, when Arabs massacred Jews in Hebron (the events in those cities are recounted in the chapters that follow). Violence continued, in various forms, throughout the country in the days that followed. But the events of that Friday were not in fact the start. The disturbances of August 1929 grew out of the relations between Jews and Arabs in Palestine throughout the 1920s. And those relations were built on the foundation, and in cognizance, of hundreds of years of Jewish-Muslim and Jewish-Arab encounters preceding the advent of Zionism. These relations were not static; they varied over time and space. Competition and cooperation, animosity, discrimination, feelings of superiority and compassion and hatred, as well as a complex of other human emotions and behaviors, all played a role. The recent and distant past are parts of human consciousness, and they were part of the emotional and political substrate of what people experienced in 1929 and how they acted during the violence. The historical memory of the inhabitants of Tel Aviv and Jaffa included a previous round of riots in 1921, eight years previously; the Jews remembered the dozens of their compatriots who had been killed then. Among the victims was the seminal Hebrew writer Yosef Haim Brenner.

Yosef Haim Brenner

Brenner was a symbol, both in life and in death. An essayist and novelist, he arrived in Palestine as part of the Second Aliyah, that wave of Jewish Zionist immigration lasting from 1904 to 1914. Central among the newcomers were young Eastern European Jews of socialist ideology who believed in the importance of manual labor and the revival of the Hebrew language, and who established the first communal Zionist settlements. Brenner was a man of great contradictions. He despaired and offered hope. He loved but suffered because of it. A tough critic of other people’s work, but a nurturer of talents. One of the great figures in the revival of the Hebrew language. One of the Zionist labor movement’s most prominent intellectuals. He often behaved, looked, and dressed oddly—some said like a prophet. For some he was the best and purest man in the Yishuv. He was killed, along with five companions, by Arabs from Jaffa on May 2, 1921, on the second day of that year’s riots, not far from an isolated Jewish farmhouse where he had been living, a short way outside the city, near Abu Kabir. The story was that the other residents had urged him to leave for safety when the violence began, but he insisted on remaining with them.

Brenner was painfully aware of Arab hostility toward the Zionist enterprise; among Arabs he felt just like he had among the gentiles who inflicted pogroms against Jews in Eastern Europe. Unlike a number of his friends, he had a hard time believing that the Jews would be able to forge an alliance with Palestine’s Arabs or with the Arab working class. Deep down, the Orient terrified him. He was certain that he would be killed by Arabs. About a year before his murder he wrote words that later seemed prophetic:

Tomorrow, perhaps, the Jewish hand writing these words will be stabbed, some “sheikh” or “hajj” will stick his dagger in it in full sight of the English governor, as happened to the agronomist Shmuel Haramati, and it, this hand, will not be able to do a thing to the sheikh and the hajj, because it does not know how to wield a sword. Yet the remnants of the people of Israel will not be lost. The stock of Jesse [the Davidic line] will not be extinguished. He will tell of our enemies to his sons—it will be told to those who remain. It will be told that we are the victims of evil, victims of the malicious ambition to gain power and property, victims of imperialism. Not us. We had no imperialist aspirations. (Y. Brenner 1985, 4:1758)

And eulogizing Avraham Sher, who had been slain in the Upper Galilee in February 1920, Brenner wrote in the monthly journal Ha’adamah: “Our savage neighbors, as always, know not what they do, whom they murder: humanity’s best” (1985, 4:1479). Many Jews felt the same way when Brenner was killed.

The Savages Know Not

The “savages” did not know who Brenner was, not before and not after they murdered him. Palestinian writing on the events of 1921 hardly mentions Brenner. When it does, it makes no reference to his important place in the life of the Yishuv or to how beloved he was. But there is another side to this story. Brenner himself knew nothing about his neighbors. His worst nightmare was Jewish integration into the Orient. Every bone in his body sensed the weakness of Zionism, the difficulty of living in the Land of Israel, and the horrors of the never-ending pogroms of Eastern and Central Europe. With all that in mind, he could not understand by what right the Arabs of Palestine opposed something that seemed to him so simple and clear and just: the desire of Jews from Romania, Lithuania, Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and everywhere else to save their lives and honor and to rebuild themselves as whole human beings, as a nation in the land of their fathers. Thus, the Arabs could only be savages, fighting against everything human and decent.

Humanity

Brenner arrived in Palestine in 1909. Between 1904 and 1911, Ibrahim al-Dabbagh of Jaffa published in Cairo a periodical called al-Insaniyya (Humanity), which was distributed in Jaffa as well. Brenner never read it, nor could he have read it had he wanted to. It presumably never occurred to him that there might be a periodical with such a name available in the port city where he disembarked. Neither did he know the extent to which the Arab press of the time identified with the persecuted Jews, and how furiously it condemned the pogroms in Eastern Europe—as shown by Shaul Sehayek in his PhD dissertation “Demut haYehudi beRe’i ha‘Itonut ha‘Aravit bein haShanim 1858–1908” (The image of the Jew in the Arabic press 1858–1908; 1991). So great was Brenner’s terror of the Arabs and so potent his disappointment at the fact that in Palestine, too, the Jews were no more than a powerless minority that he could think of no solution other than insularity and isolation from the non-Jewish environment. Only in the last essay he wrote, just before he died, did he express a shred of regret for the path he had chosen. He related an encounter with an Arab youth who addressed him as he was walking along the edge of Jaffa: “He asked me something in a clear, somewhat strident voice, clearly accented and precisely pronounced. I am sorry to say that I did not know how to respond to him, because I never taught myself to speak the Arabic tongue . . . at that moment I castigated myself harshly for never having taught myself to speak the Arabic tongue” (Y. Brenner 1962, 212).

It is a rare confession on his part. His writing makes it clear how far he was from an understanding of Arab society or even from a desire to understand it. He saw his position clearly, but he was also willfully blind to its implications. The world, in his experience, was full of hatred of Jews, and to cope with it one had to fill oneself with hatred. So he wrote to his pacifist friend Rabbi Binyamin (the pen name of the journalist Yehoshua Radler-Feldmann): “What, R. Binyamin, we are supposed to talk about love for our neighbors, natives of this land, if we are sworn enemies, yes, enemies. . . . We must, then, be prepared here also for the results of hatred and to use all means available to our weak hands so that we can live here as well. Since becoming a nation we have been surrounded by hatred, and as a result are also full of hatred—and that is as it should be, cursed are the soft, the loving” (1985, 4:1038).

Unlike Jewish political leaders, Brenner saw no reason to conceal Jewish hatred of the gentiles, the joy of having the opportunity to kill and be killed for the Jewish homeland. He felt no compunctions about declaring that war and bloodshed could be salutary, inasmuch as they could help shape and forge the nation. Others also spoke of the joy of dying for one’s homeland and the benefits of war, but it is difficult to find such clear-cut praise for hatred of the Arabs and gentiles in the works of other Zionist thinkers.

Uri, His Son

Uri Brenner was seven years old when his father was murdered. When violence broke out in Palestine in 1921, he was living in Berlin with his mother, Chaya Broide. By 1929 they had moved back to Tel Aviv, and Uri was a fatherless boy of fifteen. His uncle, Yeshayahu (Isaiah) Broide, was then serving as vice-chairman of the Zionist Executive in Palestine. Just prior to the riots Uri was tapped to enlist in the Haganah, the Yishuv’s defense force, and he immediately agreed. Along with other teenagers, he served as a messenger between the organization’s headquarters and outposts on the dividing line between Jewish and Arab neighborhoods, not far from the place where his father had been murdered. And not far from the home of the ‘Awn family. Forty years later, Uri Brenner gave his testimony for the Haganah History Archives: “The subject of the Haganah is connected to my father, and his death in 1921 was a painful subject that was repressed, perhaps because it was not spoken of at home, and perhaps because of an urge for revenge. The offer [from a member of the Haganah to enlist] was for me a saving moment in a certain sense, because I was suspended between an aggressive, avenging spirit and a defensive one” (HHA, testimony 11/7).

Uri Brenner chose an aggressive defense. In 1937 he was one of the founders and defenders of Kibbutz Ma‘oz Hayyim in the Beit She’an Valley, and a year later he joined the Special Night Squads organized by a British officer Orde Wingate, who taught that the best defense was an offense. In HaKibbutz HaMe‘uchad baHaganah (The united kibbutz movement in the Haganah; 1980), Uri Brenner wrote of the squads’ cruel and vengeful streak. In 1943 he enlisted in the Palmach, the Yishuv’s elite strike force that was closely tied to the kibbutz movement, and in the 1948 war he served as its deputy commander. In a sense, he embodied what his father had written about: “Yet the remnants of the people of Israel will not be lost. The stock of Jesse will not be extinguished.” But if Uri bore hatred of non-Jews in his heart; if he reveled at the opportunity to spill blood, as his father had; if he shared the complexities of his father’s attitude to the Arabs and the culture of force, he did not say so in anything he wrote.

The riots of 1921 were just one memory in the minds of the people of Jaffa and Tel Aviv in 1929. That is, those involved in the riots—assailants, victims, horrified onlookers, provocateurs, journalists and readers, poultry merchants, thinkers, warriors, pacifists, Jews, Arabs, Britons, washers of hands, assumers of responsibility, criers for peace—all went into these disturbances with heavy historical baggage that played a role in how they understood and responded to events. In this respect, the genesis of the disturbances long preceded their actual beginning and even the births of their protagonists. The riots’ roots reach deep into oral traditions and myths, stories of famous people; tales of real and imagined enemies told by grandparents; and legends from the Old and New Testaments and Qur’an that the people involved heard as children, in arguments their parents had with friends before the protagonists’ bedtime, while they were trying to fall asleep in their homes in Eastern and Western Europe, in the Hebron highlands and the orange groves of Jaffa, in the glens of Scotland, in Baghdad, and everywhere else they came from—while they lay in beds in proper houses or slept on rags with their siblings in a hut. The events began in souls imprinted with stories and were shaped when children had their first encounters with strangers. Traditions and stories provided the templates, and experiences were the material that, melted together, was cast in these molds—except that sometimes what came out was not the shape imprinted there but its reverse, and at other times the figure that emerged was twice as sharp as the mold itself. But it did not end there—the templates themselves were melted down and recast at junctures in these people’s lives, when they were at school or under the instruction of an Eastern European melamed or a local sheikh, when they helped their parents in the fields or served as cheap hired labor. That was when their political and nationalist consciousness awakened—or did not.

It would be best, then, to start in all those places at once, but that is not possible. A writer has no choice but to choose a starting point and to move forward and backward in time, keeping in mind always the gap between what he knows and what people knew at the time.

Knowledge Gaps

The participants in and observers of the events of 1929 knew their times better than anyone who did not live through them. However, we have knowledge of what happened in their future, which they obviously lacked at the time. We know what happened in Hebron and Motza and Jaffa and Safed and Hulda and Jerusalem and Acre and Migdal ‘Eder and so on, while they, in real time, saw only what was happening before their eyes. We also know how events progressed after the riots, that animosity between Jews and Arabs did not end, and that there was a fateful war in 1948 in which the Arabs were defeated and during which the State of Israel was founded. We know that hundreds of thousands of Arabs became refugees and that the conflict continues. This knowledge makes it difficult for later generations to view events from the perspective of those who lived through them. Jews today have trouble really feeling the dread felt by Jews who lived as a persecuted minority (even if some observers believe that existential fear is the key to understanding Israel’s actions in the present). Palestinians today have trouble imagining Palestine as it was at the end of the 1920s, part of a spacious Arab land from which one could travel unimpeded to neighboring Arab countries and within which were scattered, here and there, Jews who were trying to gain a foothold in the country and to take control of it.

But all that is connected to how the events played out and turned out. We are still at the beginning, in Jaffa in 1929, seeking to understand what happened in this city and what we can learn from what happened there regarding the 1929 riots as a whole. Before we investigate what occurred in the ‘Awn family’s house, let’s take a look at the book in which their story appears: Biladuna Filastin (Our land of Palestine).

Our Land of Palestine

The first volume of the Biladuna Filastin encyclopedia was published in 1947. The set was completed in 1965. Al-Dabbagh relates in his introduction to the new complete edition: “When I issued the first volume of my book, I did not imagine that the Nakba would take place in the country within the year and disperse its inhabitants as a storm scatters the sand” (2002, 1:7). He goes on to describe how, at the height of the fighting, before Jaffa fell, his cousin arrived on a boat from Egypt and persuaded him to sail away, in so doing saving his life:

I did not take anything on the trip except for a small suitcase containing the manuscript of more than 6,000 pages of my book on the history and geography of Palestine, my only book, the product of more than a decade of collecting material and writing. I blessed God for the fact that, a few days earlier, I had sent my wife and children to relatives in Beirut, and boarded the ship with my cousin and his friends, uprooted as we were.

The sea was rough, the waves rolled and roared, a gale raged and a hard rain fell. Water began to enter the boat on all sides. The captain shouted that we should cast the cargo into the sea to lighten the boat, otherwise it would sink. I held my suitcase fast to my breast, but the arm of a tough sailor, aided by a wave that fell over the ship, separated the suitcase from me and hurled it into the sea. So the book was lost to me and with it the labors of many years. (2002, 1:7)

Al-Dabbagh spent another fifteen years reconstructing his manuscript, and later in his introduction to the complete edition he offers the principal conclusion of his research: “The book shows that the Jews’ claim of a historical right to the land is baseless. The claim is unsubstantiated in a manner without historical precedent, a bald fabrication. . . . The Jews have passed through our homeland, as have other nations that have vanished from the earth” (2002, 1:7).

Reading the Final Sentence Precisely

Three points in the last of al-Dabbagh’s sentences quoted above are worthy of note. First, he acknowledges that the Jews were once present in Palestine. That is not to be taken lightly. It contradicts a popular Palestinian claim then and now that the Jews of today are not descendants of the Israelites of old but are rather, for example, Khazars. The second important point is the claim that the Jews’ presence in the country in the past does not validate their claim to sovereignty in the present—they came to Palestine during their wanderings in the past, and now they are passing through once more. The third and central point is encompassed within the term “our homeland.” For the Arabs of Palestine, the country is their homeland from before the Hebrews or Jews first reached it, and they continue to be its natural inhabitants and heirs. This is a fundamental Palestinian concept. The fact that Palestinian society is composed of families and tribes—some of which have roots in Palestine and others of which arrived in waves of immigration over the years, prior to Islam and afterward—does not, in this view, diminish this claim, because by its nature Palestine is a land that serves as a melting pot for its inhabitants and melds them into a single Palestinian people.

This Palestinian perception, which frequently sees the Jews who lived in Palestine prior to the inception of Zionism as part of the Arab Palestinian people, is profoundly opposed to the common Zionist Jewish view. First, Palestinian nationalism is based on the principle of jus soli—right of land. That is, it is the land that creates the nation, and the inhabitants of a country possess the right to it, no matter what their origin. The rival Jewish perception is based on the principle of jus sanguinis—right of blood. In this view, blood descent is the central component of nationhood, and the right to the Holy Land derives from its association with the Jewish people. The practical implications are, then, that the Palestinians see the land as their homeland and the Jews as foreigners (who can, under certain conditions, merge with the Palestinian people), while the Jews see it as the homeland of the Jewish people, no matter where they may be. But let’s return to Jaffa in 1929 and search for further sources of that year’s killings.

More Sources on the Murder in Jaffa

Further information on the ‘Awn family’s murder can be found in contemporary newspapers. They did not report the crime when it occurred, but they did cover the trial of Simha Hinkis, a Jewish policeman arrested by the British as a suspect in the crime. A large amount of material on the case can be found in the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem and in the National Archives of the United Kingdom, and the incident is also mentioned in Sefer Toldot HaHaganah (The Haganah history book; Dinur 1973), a history of the Yishuv’s major military force, written in the 1950s.

The Haganah History Book

Sefer Toldot HaHaganah is considered a classic of the “old history”—that is, traditional Zionist historical writing—because it tells the story of the Yishuv and the Haganah from the point of view of the central current of Zionism at the time, the labor movement. The work was a collective undertaking, and the names of its authors make it tempting to view the book as having a manifestly political agenda. The principal writer was Yehuda Slutsky, a professional historian and writer; the editorial board’s members included Shaul Avigur (whose previous assignments included being chief of the Haganah’s intelligence service and one of the leaders of the illegal immigration operation that brought European Jews to Palestine in violation of British immigration restrictions), Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (a leader of the Second Aliyah, one of the founders of the Haganah, and later the second president of Israel), Elazar Galili (nicknamed Lasia, head of the Haganah’s Culture Department, founder of Ma’arakhot, the official journal of the Israel Defense Forces, and a member of Kibbutz Afikim), and Yisrael Galili (whose posts included chief of the Haganah’s national command in 1947–48, member of the Knesset, and member of the cabinet in 1966–77). The chief editor was Ben-Zion Dinur, a prolific historian of the Jewish people who served as Israel’s education minister from 1951 to 1955. But the work was not just a megaphone for the political ideas of its writers and editors. Its thick volumes contain a trove of information, including about the “Hinkis incident” (a euphemism for the murder of the ‘Awn family). The fact that the “incident” was included is just one of many examples that show that the authors and editors did not, as a general rule, seek to conceal problematic parts of the Zionist project in Palestine, but they present such incidents in soft focus. Here is what the work says about the murder: “A short time after this event [the killing of members of the Haganah in Abu Kabir], several Jews, among them the policeman Simha Hinkis, broke into one of the Arab homes in Abu Kabir that were adjacent to Tel Aviv. Four Arabs, among them a woman and a child, were killed. It was an act of retribution, the product of an emotional outburst, after news of the massacre in Hebron reached Tel Aviv and after the murder of Jews who had set out to save human lives” (Dinur 1973, 2:327).

Note that Sefer Toldot HaHaganah gives a different figure for the number of dead than does al-Dabbagh. Was it four or seven? The indictment and judgment in Hinkis’s trial will provide an answer.

And what about the event that, according to the Haganah history, preceded Hinkis’s raid on the house? Who were the Jews who were murdered in Jaffa? The answer can be found in Sefer Toldot HaHaganah: On Sunday around noon, a day after the massacre in Hebron, a Haganah patrol set out to rescue Jews who had been trapped in an ethanol factory outside Abu Kabir that was being besieged by Arabs. The British ordered the patrol to return to Tel Aviv and sent a British unit to disperse the Arabs and evacuate the besieged Jews. The Haganah patrol headed toward Tel Aviv, and, according to the book, “on its way back the group of defenders encountered an Arab mob that was, apparently, guarding the entrances to its neighborhood, and it attacked the [patrol’s] vehicle. Four Haganah men were killed” (Dinur 1973, 2:327).

Jaffa: A Historical-Literary Reader

The account in Sefer Toldot HaHaganah is pretty concise. A more comprehensive picture of the events can be found in Yafo: Mikra’ah Historit Sifrutit (Jaffa: a historical–literary reader), published in 1957 by the Education and Culture Department of the Tel Aviv–Jaffa municipality. The editor was Yosef Aricha, at the time an important and influential writer of Hebrew fiction. The book includes memoirs, poetry, and a history of the city from biblical times to Jaffa’s surrender to Zionist forces in 1948, written by dozens of writers. One of its chapters is devoted to the 1929 riots in and around the city. Here is the general background the book offers:

In Tel Aviv the riots began on Sunday, 19 Av 5689 [August 25, 1929], after an inflamed Arab mob emerged from the Hasan Beq Mosque south of Tel Aviv. The Arabs had long prepared for an attack on the city. The sheikhs and effendis incited the fellahs and poor people to stage a massacre of the Jewish Yishuv and promised them their wives and daughters. Each Arab who promised to take part in the attack was given a pack of cigarettes and a shilling. Thousands of inflamed Arabs, craving loot, gathered from the entire region and in the afternoon commenced their attack on Neveh Shalom and next to HaCarmel Street from the alleys across from Allenby Street. (Hinkis 1957, 229–30)

So Tel Aviv was also attacked in 1929. The street called HaCarmel then is today’s King George Street, in the heart of Tel Aviv’s downtown, and that is where the first act of the offensive took place. To be continued.

An Inflamed Mob?

The term “inflamed mob” connotes that the mob lacked any ideological motivation or judgment of its own. It is derisive of the people in the mob, as they have been inflamed by someone and are following his or her exhortations rather than thinking for themselves. Inflamed mobs have three attributes: first, they operate outside any organized framework; second, they are irrational; and third, they are not acting of their own volition. The attackers in Jaffa, Hebron, and other places in 1929 meet the first criterion, as they were not part of a professional force on a mission and had not been trained as fighters. Rather, they were a large group of people who were driven to act after learning (or hearing rumors about) what had happened in Jerusalem. The other two criteria are more complicated, as they have to do with the attackers’ logic and judgment and their motivation for acting. The author of the quoted part of Yafo maintains that their motive was a vile one—effendis (members of the new economic elite) and sheikhs (religious leaders) incited the masses and distributed measly gifts—and the masses, mostly poor people, went on the attack. They did not truly understand the significance of their actions and did not consider the moral implications. For them, human life was worth less than a pack of cigarettes.

Is that convincing? Were these Arabs really goaded into action by a pack of cigarettes and a shilling? By dreams of beautiful women—a motive frequently cited in Jewish accounts of the events in both Jaffa and Hebron? The explanation is attractive in its simplicity, but I am not certain that it is sufficiently comprehensive. The claim that the Arab masses of 1929 had no powers of judgment is unpersuasive for the simple reason that there were people who attacked and people who refrained from doing so. The explanation is also invalid for another reason—had these same people been offered a pack of cigarettes in exchange for murdering their own friends and families, would they have done so? If the answer is no—as presumably it would be—the only possible conclusion is that these attackers had stronger motives than just immediate gratification. We may also presume that the incitement encouraged an outbreak of already existing animosities, rather than creating new ones.

The concept of the “inflamed mob” has another flaw: implicit in the phrase, for many, is an assumption of the moral inferiority of the mob as opposed to organized forces. But this is not necessarily true. Just as organized forces can act with or without a moral compass, so can a seething (or “inflamed”—that is, responding to emotional appeals directed to it) mob. Jaffa’s own history provides an example.

Napoleon in Jaffa

A memorable event in Jaffa’s long history is its conquest by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1799. French forces had captured Egypt a year earlier, and at the beginning of 1799 they began moving overland toward Palestine, from El-Arish to Gaza and from there to Ramla. During the campaign the French took thousands of Ottoman prisoners, whom they took with them on their northward progress. On March 3, Napoleon’s army reached Jaffa and besieged it. The city resisted for four days before falling. French soldiers looted Jaffa’s homes and slaughtered many of its inhabitants. Two days later, the French led 3,000 prisoners southward on an organized march. Just outside the city limits, on the seashore, they were divided into small groups and shot dead by French soldiers. The executions lasted for hours. Those who were not killed by the bullets were stabbed to death with bayonets.

Napoleon and his men justified the massacre on the ground that they did not have enough troops both to guard the prisoners and defend their positions, adding that they also lacked food for the captives. They claimed too that the Ottomans had been the first to violate the customary laws of war—the Ottoman governor of Jaffa had had beheaded the messenger that Napoleon sent him. Even more critically, the Ottoman prisoners who had surrendered in the country’s south and were subsequently released violated their pledge to stay away from the battlefield, instead joining the forces defending Jaffa. Of course, logical, political, and moral justifications have been offered for almost every massacre from the dawn of history to the present day.

So Muslims are not the only ones who can commit atrocities—European Christians are fully capable of doing so as well. And not just any Europeans—this was the army of the French Revolution, spreading the gospel of liberté, egalité, and fraternité. In Napoleon: His Army and His Generals, Jean Charles Dominique de Lacretelle wrote that the piles of bodies in time turned into pyramids of bones. These monuments to the dawn of modern cultural interaction between the West and the Levant long stood on Jaffa’s beach (1854, 106).

The Modern Age

Napoleon’s eastern campaign—the conquest of Egypt and capture of Jaffa (commemorated in several classic paintings)—is often seen as the beginning of the modern age in the Middle East. But it did not exactly put Western-style modernity’s best foot forward. At a conference on religion and the state held at Bar-Ilan University in May 2011, the Indonesian historian Azyumardi Azra spoke of the far-reaching consequences of the event in another sense. He argued that Middle Eastern Islam developed in the direction of intolerance as a result of the siege mentality under which the Arab world lived after Napoleon’s attack. It was this, he claimed, that impelled the Arabs to avoid interaction with the West and to turn toward sectarianism (Mandel 2011).

From Napoleon’s Massacre to 1929

Napoleon’s slaughter of his prisoners is an inevitable association when the subject is massacres in Jaffa. But there is another reason why I mention it here: to correct a historical distortion—or, rather, to cleanse that distortion from the minds of those who maintain that only an inflamed crowd or only Muslims are capable of committing a mass murder of innocent people. That claim is manifestly without foundation, yet the more it is shown to be so, the more some people seem to assert it. After the horrors of World War II nobody really needs to be reminded that Europeans are capable of mass murder. Nor did Jews need such a reminder in 1929. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, pogroms were part of everyday life (and death) for Jewish communities in Eastern Europe (and less so in Central Europe), and by 1929 dark clouds were gathering over the entire continent.

We’ve cited Christian brutality and Muslim brutality. Now we need to examine the Jews and mass murder.

What about the Jews?

During the nineteenth century, in Palestine and throughout the world, Jewish involvement in massacres was very one-sided—they were always victims. One example is the Peasants’ Revolt of 1834, a seminal event in the history of Palestine. Some background: About thirty years after Napoleon’s campaign, a dispute broke out between the Ottoman sultanate and Muhammad ‘Ali, who ruled Egypt under nominal Ottoman suzerainty. The dispute was about the sphere of the Egyptian ruler’s influence and the extent of his powers. Muhammad ‘Ali took military action, sending forces northward that conquered large swaths of the Levant, up to the border of what is Turkey today. He controlled Palestine for about a decade (1831–40), during which time he instituted important changes in its administration, as well as in the social and legal sphere. Among other things, he introduced mandatory conscription and mandated legal equality for Jews and Christians, putting them on a par with Muslims. Keep in mind, however, that conferring equal rights on minorities is tantamount to depriving the majority of its privileges. That is one reason why majority communities throughout the world often oppose the concept of equal rights so vociferously and sometimes violently. The history of European Jewry during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries offers a notable instance of this. But there are even more recent examples.

In 1834 the Arabs of Palestine rose up against the Egyptian administration and its innovations. In Palestinians: The Making of a People (1993), Baruch Kimmerling and Joel Migdal present this revolt as marking the first glimmering of Arab nationalism in Palestine (many other scholars dispute this claim, for a variety of reasons). The rebels were led by the most powerful families in the region’s rural areas. The revolt encompassed all of Palestine, from Gaza in the south to Safed in the Galilee. At the end of May the rebels attacked Jerusalem, and with the help of the city’s Muslims they reached al-Haram al-Sharif, the Temple Mount. From there, masses of rebels and local Muslims marched toward Jaffa Gate, pushing back the Egyptian forces step by step. Muhammad ‘Ali’s troops retreated into a fortress near the gate, now known as David’s Citadel; the rest of the city fell to the rebel villagers. The conquerors began to plunder the city. Muslim homes and establishments were not touched; their owners may well have joined the looters. Christians fled for their lives into fortified monasteries.

The city’s Jews bore the brunt of the attack. In 1938 Asad Rustum of the American University of Beirut published Egyptian documents relating to the revolt. He cited this passage from a report on Jerusalem: “The homes of the Jews were demolished completely, leaving them without beds to sleep on. Many of them were slaughtered and their wives and daughters dishonored.” In Safed the rebels broke into the Jewish quarter, “looting and violating the accepted bounds of decency and honor” (1938, 60). Despite Muhammad ‘Ali’s ostensible liberalism toward minority groups, the Jews in Hebron found that they could not depend on his protection when his forces defeated the rebels. The commander of the Egyptian troops gave his men a free hand to rape and plunder, “and boldness entered into their limbs and murder into their bones. They killed some with torches and some they slashed with swords. Many women were tortured and sullied,” the members of the community wrote of the disaster after they rose from their period of mourning (Avisar 1970c, 56).

One Law for Jews, the Uncircumcised, and the Ishmaelites

Bloody events like these were not routine. While Jews did not enjoy equality under the Ottoman Empire, in Palestine and elsewhere, prior to the era of nationalism, it was one of the easiest places in the world for Jews to live. At the beginning of Igrot Eretz Yisra’el (Letters from the Land of Israel; 1943), Avraham Yaari quotes a number of letters penned at the beginning of the modern age that contain material relating to the condition of Palestine’s Jews under Mamluk and Ottoman rule. The writers of the letters, he notes, emphasize

that the regime does not discriminate against the Jews and that the Arab inhabitants harbor no special hatred of the Jews as Jews. The writers stress in particular that there was no contempt for the Jew and his faith, the kind of contempt that had become etched in their souls during their time living in Christian lands; they declare in astonishment that the Arabs honor Jewish holy sites and the tombs of Jewish saints.

Rabbi Yitzhak Latif writes in his letter from the last quarter of the fifteenth century: “The Arabs are at peace with us. They will never strike us and never pillage.” At about the same time, Rabbi Yosef da Montagna declared in his letter from Jerusalem: “On the way we were sometimes in the field among many Ishmaelites and I never heard a man open his mouth to speak evil.” A few years later, in 1488, Rabbi Ovadiah of Bartenura wrote in his first letter from Jerusalem: “The Jews feel no sense of repression at all from the Ishmaelites in this place; I have traveled the length and breadth of the country and no one opens his mouth or jeers.” A student of this same Rabbi Ovadiah of Barentura describes in a letter the punishments imposed by the authorities, remarking that “as a rule, there is a single law for the Jews and the uncircumcised [Christians] and the Ishmaelites, but they do not hate Jews and castigate and abuse them as in your country [Italy]. . . .” In the mid-eighteenth century, Rabbi Avraham Gershon of Kitov wrote from Hebron: “The gentiles here very much love the Jews. When there is a brit milah [circumcision ceremony] or any other celebration, their most important men come at night and rejoice with the Jews and clap hands and dance with the Jews, just like the Jews.” (Yaari 1943, 18–19)

The letters include additional accounts of close interaction and cooperation between Jews and Muslims, certainly much beyond what was customary in Europe. The attack on the Jews in Jerusalem, Hebron, and Safed during the uprising of 1834 was thus an exception that proved the rule of generally placid, if not equal, relations between the Muslim majority and the Jewish minority. But they also marked the beginning of a change for the worse for the Jews. Here it is important to be precise: the assaults on Jews during the revolt indicate that anti-Jewish sentiment did not begin to increase solely as a reaction to organized Zionist activity in Palestine. In 1834, that had not yet begun. Rather, it seems to have been a response to Western attempts to gain political and economic control over Palestine and the Middle East as a whole. The role that the Jews played in this process—their increased immigration to Palestine during these years, and the support they enjoyed from European governments—aroused resentment against them.

Pre-Zionist Anti-Zionism

It can be put this way: European penetration of the Middle East heightened awareness of the difference between the Muslim majority community on the one hand and the minority Christian and Jewish communities on the other. Christians and Jews appealed to the European powers with the goal of improving their legal and economic status and gaining full equality, and in doing so were often seen as promoters of foreign interests and non-Muslim rule. So political enmity began. The Jewish and Christian alignment with Christian powers also had religious significance; the choice Jews (and Christians) made to prefer the protection of foreign powers was interpreted, understandably, as an act of renouncing their traditional status as wards of the Muslim sovereign. For Muslims, this was a watershed in their relations with these communities. Legally and theologically, from that point onward Muslims viewed themselves as absolved of the obligation to protect the Jews and Christians of the Holy Land and elsewhere in the Middle East. Furthermore, if the Jews wished to turn Palestine into their own land, as rumors began to say they did, the Muslims were bound to fight them. Political contention between the Jews and Muslims thus commenced prior to the dawn of organized Zionist settlement, even before the arrival of the proto-Zionist settlers of the Bilu and Hovevei Zion movements in the nineteenth century’s latter decades.

Implications for Today

Arabs commonly viewed the Jews in Palestine as colonialists and emissaries of Western imperialism. This seems to have been the background against which many Arabs understood, and still understand, the Jewish-Arab conflict. The basis for the evolution of this view can be found in the 1830s. During that decade, under Muhammad ‘Ali’s rule, Jewish immigration to Palestine increased with the help of foreign powers, and this continued after the reassertion of Ottoman control over the country. The British consulate that opened in Jerusalem in 1839 took under its protection all Jews who were neither Ottoman citizens nor citizens of any other European power, and its staff was inspired in part by the belief that it was God’s will that the Jews return to Zion (Schölch 1993). Palestine’s Arabs were aware of the messianic Zionist outlook of many British officials, and this was a source of their perception (and inference) that the Jews and Europeans had concluded an anti-Islamic compact aimed at establishing a Jewish-Western territorial outpost in Palestine at the expense of its Arab inhabitants. While the Jews who came to Palestine at the time did not see themselves as agents of the European powers but rather as their wards, and their main goal was to live their lives free of the constant threats and discrimination they had endured in their countries of origin, the Arabs viewed their arrival as part of a deliberate project of dispossession. From the Arab perspective, all of the events of the decades that followed—the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the UN partition resolution of 1947, the Israeli, French, and British attack on Egypt in 1956, and European and American aid to Israel since its establishment—have confirmed their belief that Israel is a tool of the Western powers in the Middle East.

Back to Anticolonialism, Colonialism, and Murder

We can draw some interim conclusions from our comparative look at the conduct of Napoleon’s army in Jaffa in 1799 and that of the Arab rebels in Jerusalem and Safed and of Muhammad ‘Ali’s army in Hebron in 1834. Clearly, an unorganized mob, an organized army of conquest, and a rebel force are no different in this respect: in all three cases, national and religious rivalries, combined with superior force and a measure of frustration, can make the forbidden (looting, murder, or rape) permissible. Studies of mass psychology show that there are deeds that we do not permit ourselves to commit as individuals, but that we may well commit when we become part of a collective action. We also know that what is perceived to be out of bounds in everyday life can, at times, be seen as acceptable in a crisis.

But it is still important to keep in mind that there are different kinds of violent mass actions and that each of them presents different moral issues. There is action against the authority of an exploitative ruler (for example, the storming of the Bastille or certain incidents in the Algerian war of liberation), action against a vulnerable minority (Ukrainians against Jews or lynchings of blacks in the American South), and contention between equal groups in which both sides conduct pogroms (episodes in the interethnic war in the former Yugoslavia).

Where Does 1929 Stand on the Scale?

This is one of the principal questions under dispute. To answer it, we need to try to determine the facts that everyone can agree on. It is a fact that the Jews were at that time a numerical minority in Palestine. It is a fact that most of them aspired to achieve Jewish sovereignty, even if they did not always use those words explicitly. It is a fact that their actions were detrimental to the national aspirations that the country’s Arabs had begun to develop at the same time. It is a fact that a decisive majority of Jews had no intention of harming the country’s Arabs, at least not directly. It is a fact that they did in fact do them harm at various levels. It is a fact that on other levels the country’s Arabs benefited from the presence of the Jews. The upshot: The Arabs viewed the Jews as foreign usurpers. The Jews viewed themselves as members of a persecuted minority that returned to its homeland. Many Arabs perceived their struggle to be an anticolonialist one, even if, at the time, they used this terminology only sparingly. Many Jews viewed Zionism as a national liberation movement and the Arab uprisings as an extension of the pogroms they had experienced as a minority in Eastern Europe.

The question of whether the Arabs were conducting pogroms or fighting a war of liberation is, of course, linked to the question of whether Zionism has been a colonialist movement.

Has It Been Colonialism?

In addition to the British support for Zionist aspirations, the claim that Zionism is a colonialist movement is based on the following assertions: it is a movement that worked to transfer a European population to a region inhabited by a less technologically developed, and thus weaker, population (as in other colonialist movements); its members settled in that region without the consent of the local population (as with other colonialist movements); its members felt themselves to be fundamentally superior in culture to the native population (as in other colonialist movements).

Those who dispute the charge also offer serious arguments: the Zionist movement was not a great power; Zionist settlers did not have the support of a powerful country where they enjoyed full and equal citizenship, as most other European colonialists did; the Zionists did not intend to exploit the local population as cheap labor as other settler societies did; and the Zionists did not work to extract the resources of the land they settled and send those resources to another country, as colonialists generally do. Another argument is a historical one—the Jews were not in fact foreigners in the country but rather natives whose ancestors had been sent into exile generations previously. Thus Zionism, in the eyes of its adherents, is a national liberation movement that calls on Jews to return to their historic homeland. (Fundamentally, the debate over whether Zionism is colonialism is a political one; God is present only at its margins. There is a parallel polemic, a religious one, over the question of whom God gave the land to—which is the subject of the next chapter.)

This complex picture means that Zionism can be seen as a movement that combines nationalist and colonialist aspects. The Jews experience it primarily as a realization of their goal as a nation, while the Palestinian Arabs experience it as colonialist. That explains why Zionism did not view those fighting it as anticolonialists but rather as an inflamed and ignorant mob that did not appreciate the benefits that Jewish settlement brought to the country and opposed the progressive values that Zionism promoted.

Ironically

Colonialists everywhere have viewed local inhabitants who opposed them as an inflamed and ignorant mob opposed to progress.

An Example from 1929

Maurice Samuel, a Jew born in Romania in 1895, moved as a child to England with his family, where he attended high school and the University of Manchester (in Manchester he met and became fond of Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader). He then emigrated to the United States, where he was conscripted and served in the army in World War I. After his discharge he served as an interpreter at the Versailles peace conference and on the Morgenthau Commission investigating the pogroms in Eastern Europe. Subsequently he joined the staff of the World Zionist Organization’s New York office, and in the mid-1920s he published several books in which he wrestled with the question of the Jews’ role in Western history and their relations with non-Jews. Samuel was in Tel Aviv when the 1929 riots broke out, and he volunteered to serve in one of the contingents that the Haganah organized to defend the city. Shortly after the riots he published a widely read book about them. In one passage, he recalls his own thoughts and those of other guardsmen at a lookout point:

To complete the caricature, we could not help feeling that in this petty squabble (for such it was bound to appear to us) we did stand on the side of a principle. And the principle was symbolized for us there by the scene at our feet. On the one side lay Tel Aviv, a city which had sprung up in twenty years on empty and forbidding sands. A city that was modern in the least objectionable sense; peopled by men and women conscious of social and intellectual purposes. On the other side, Jaffa, a very ancient city, a city typical of the decayed East, with a few rich and many poor—and a poverty of that awful and indescribable type which can be found only in the East. . . . On the one side Tel Aviv with its poets and painters and thinkers. On the other, backward Jaffa, in which education is a fantastic luxury, and modern intellectuality—in a levantinized form at that—the possession of a handful. (1929, 75–76).

The author underscores, with an arsenal of literary techniques, the fact that he is rooted in Western culture, just like other Zionists, and in contrast with the backward Arab masses. He writes at length about the events of the day as a whole, but completely disregards a specific event that took place quite close to his guard post—the murder of the ‘Awn family.

Perhaps mentioning it would have weakened the thesis of his book. He mentions a Jewish wagon driver, Baruch Rozin, who was murdered nearby, and the killing of the Haganah troops who went out to rescue the Jews who had been trapped in the ethanol factory. Those deaths were compatible with the image he wanted to foster.

The Murder of Rozin the Wagoner

On Sunday, the day of the attack on Tel Aviv, Baruch Rozin the wagoner was moving out of his home in Neveh Shalom into a new apartment in the center of town. Not far from the Hasan Beq mosque, as he and his sons Aharon and Leib made their third haul of his belongings, they ran into an Arab mob advancing from Jaffa toward Tel Aviv. Aharon was driving the wagon while Leib and his father walked alongside. The mob approached and they heard voices calling out “Udrub [beat them]!” A wave of Arabs surged forward and attacked them with poles and sticks. Leib managed to get away, running toward Tel Aviv; Aharon, slightly wounded, evaded the mob, and also fled northward. He almost collapsed a short while later, and a passing car rushed him to a hospital. Their elderly father was beaten again and again until he died. An autopsy found a bullet entry wound. Apparently someone shot him at short range. Binyamin Plastovsky, a police officer, was on duty nearby. He later testified that he saw, from a distance, a mob attacking Jews, but he was deterred from getting any closer because he was alone. When the mob dispersed, he approached and found Baruch Rozin’s body (record of the trial of the attackers, October 10, 1929, CZA L59/58).

What Does Al-Dabbagh Say about That?

Al-Dabbagh does not mention the attack on the ethanol factory, the killing of the Haganah men in Jaffa, or the murder of the wagoner Baruch Rozin, all of which took place on the same day that the ‘Awn family was slaughtered. He also has a nationalist outlook he seeks to promote and a set of images he uses to that end.

A possible inference: both sides engage in similar techniques of denial, repression, and cherry-picking the events they write about. In other words, they use like methods of constructing a national narrative. In this regard, there is no difference between Western and Levantine intellectuals. Another inference: each writer mentions the victims that he cares for, those who are closest to him.

The Seething Mob: A British View

In normal times, some of the British in Palestine were attracted by the vibrancy of Jaffa. Some of them took a romantic, Orientalist view of it. Others were put off by the city. One account of the beginning of the troubles comes from a British officer, S. C. Atkins:

At about 1200 hours I received information that a mob was preparing to attack the Governorate. . . . [B]y this time some 2000 Moslems had collected in the Square and about 100 were already on the Governorate steps, although the mob was disorderly and excited, I do not think that there was any intention to attack the Governorate, furthermore any attempt would have been easily repulsed since I had a cordon of Police with batons at the entrance of the Governorate and an armed guard in reserve inside (out of sight). Seeing that this was the time for pacifying the mob, I cleared the Governorate steps using [as] little force as possible and then proceeded in amongst the crowd explaining what would happen if they did not clear, in a few minutes the square was clear. A little later, however, on the arrival of a wounded Moslem, a mob again began to collect shouting we want a “Turkish Government” (the Ringleader has since been arrested), the mob was dispersed in a manner similar to the former and the square was again clear. (Atkins 1929, 1)

Atkins’s temperate mob control method turned out not to be effective when more Arab casualties were reported. The mob gathered again, he reported, and at this point he had no choice but to fire shots in the air.

A Reminder

When attacked by natives, an officer with military experience, serving an imperial power, experiences the incident differently than do the members of a civilian community attacked in their home city, even when they are targets of the same attack. What is the significance of this difference? And to what extent are the attackers aware of it? Hard to say.

Isma‘il Tubasi, Incendiary No. 1

The term “inflamed mob” presupposes that someone has inflamed it. The British police in Jaffa identified two incendiaries prior to the outbreak of violence. In the district police log Officer Alfred Riggs (the policeman who repelled the attack on Tel Aviv and who arrested Hinkis) recorded what happened that morning. At 8:00 a.m., he wrote, a crowd gathered at the mosque. Orators spoke of the Western Wall, and Isma‘il Tubasi gave a fiery speech. Some of the older sheikhs tried to cut him off, without success. He got so emotional that he fainted and had to be revived and carried away. His talk, Riggs said, had a very bad effect on the audience.

In his testimony before the commission of inquiry, Riggs offered a more detailed account of what Tubasi said. Riggs placed the event at a slightly later hour, but the substance was the same: “[At] about 10.00 hours he [Sheikh al-Muzaffar] addressed the people. He asked them to refrain from demonstrating and told them to be quiet. Ismail Tubassa [sic] rose and said: ‘In the name of God, in the name of Mohammed and religion, we do not want protests; we are ten years protesting but without results. This protest will receive the same fate as the others, we must demonstrate, attack our enemies by ourselves, lose our lives for the country.’ He was excited and made the assembly very excited” (Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929 [hereafter Commission] 1930, 2:997–98).

Tubasi, as his name indicates, came to Jaffa from the town of Tubas in northeastern Samaria. He had been born in 1907 and was twenty-two years old in 1929, having just completed his studies at the Islamic College in Jerusalem. Following the riots he was sentenced to imprisonment for incitement. After his release he served for several years as a leader of the Arab Scouts in Palestine, working also as a teacher and journalist. In the war of 1948 he joined the forces defending Jaffa. After the city’s fall he returned to his hometown of Tubas, where he taught at the local high school. In 1979 he published in Amman a book titled Kifah al-Sha‘ab al-Filastini 1908–1965 (The struggle of the Palestinian people). His speech in Jaffa in 1929 was his first public appearance.

Stalin’s Man in Jaffa

A second activist involved in the events in Jaffa—a provocateur, according to the police—was Hamdi Hussayni. He personified a different social and political phenomenon than Tubasi did. Born in Gaza in 1899 to one of the city’s prominent Muslim families, he was sent to a church high school. At the end of World War I he went into journalism, eventually serving as editor of al-Karmil in Haifa, one of the most important Arabic periodicals in Palestine, and writing for other publications. At the beginning of the 1920s he served as a teacher in Ramla. About seventy years later, ‘Abd al-Rahman Kayyali, who had been a student of his, related how proud he and his fellow students were when Hussayni refused to stand up in respect during a visit by the British high commissioner to the town (Shina’a 1993).

In 1927, Hussayni assumed the editorship of the Jaffa newspaper Sawt al-Haqq (Voice of truth) and served as an active member of the anti-British Young Muslim Association, in the latter capacity helping promote a manual laborers’ union. As a result of this activity, the Palestinian Communist Party invited him to participate in an international conference of the League against Imperialism, organized by the Comintern in Germany in 1928. He seems to have made a very good impression on the participants (he was not just an analyst and organizer but also spoke several languages, among them Spanish, Italian, Hebrew, and Turkish). He was then invited to Moscow, where he met Joseph Stalin and other senior figures.

When Hussayni returned to Palestine, he was placed under surveillance by the British secret service. He was still being followed during the tense days of August 1929. British police officers who testified before the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929 (the Shaw Commission) referred to him as a professional troublemaker. He tried to stir up the crowd politically, they said, but quickly realized that religious appeals were an easier way of influencing the masses. He thus adopted the claim—commonly voiced by the mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Hussayni—that the Jews were trying to take over al-Aqsa.

Communist sources depict Hamdi Hussayni in a different light. Leon Zahavi, an Israeli Communist activist and the Israeli Communist Party’s representative in Moscow, refers to Hussayni as a “well-known nationalist revolutionary” and relates that Hussayni advocated directing the struggle against the British, not the Jews (Zahavi 2005, 155, 178), because the struggle should be anti-imperialist, not nationalist. The 1929 pogrom, Zahavi writes, occurred because the communists in Palestine did not succeed in taking charge of and organizing the struggle.

In any case, Hussayni received in his office in Jaffa a telegram from the Committee for the Defense of al-Buraq (the Western Wall) asking him to organize demonstrations in his city in response to the Jewish procession to the site. He does indeed seem to have been involved in organizing the demonstrations, but we do not know what he thought about the attack on Tel Aviv.

And One Who Did Not Incite

A third prominent figure in these events was Sheikh ‘Abd al-Qader al-Muzaffar, one of the leaders of the Palestinian national movement at the time and a man of great public influence. Al-Muzaffar was born in Jerusalem in 1892 to a family of ‘ulamaa (Islamic scholars). He pursued advanced studies at al-Azhar Institute in Cairo, graduating in 1918. Al-Muzaffar spent the period following World War I in Damascus, along with other nationalists who gathered in the city in the hope of taking part in the establishment of a large and united Arab kingdom encompassing the entire Arab east (the territory that later became Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel-Palestine) under the rule of Faisal ibn Hussayn of the Hashemite clan. While in Damascus, al-Muzaffar maintained friendly relations with another native of Jerusalem, Yosef Yoel Rivlin, then headmaster of the Hebrew school for girls in Damascus and later a translator of the Qur’an into Hebrew (and father of Israel’s President Reuven Rivlin). Yosef Rivlin referred to al-Muzaffar as a leader of “the extremist anti-Zionist clique in Damascus” (“Beit-Hashem beMa‘arbolet,” Hed haMizrah, March 17, 1950) But he also recalled that in the 1930s al-Muzaffar sent his nephew to study Qur’an exegesis under Rivlin at the Hebrew University, and that the sheikh, then living in Jaffa, took a great interest in the innovative interpretations that his nephew learned from Rivlin. In 1923, when the British announced elections for a legislative assembly in Palestine in which seats would be apportioned on a religious basis among Muslims, Christians, and Jews, al-Muzaffar was among the leaders of the campaign for a boycott of the elections. Only a few men declared their candidacies, and the voter turnout was extremely low. In the end the British decided not to establish the assembly. It was one of the most important of the (very few) successes of the Palestinian national movement during the Mandate period, but it had a negative impact in the long run.

Al-Muzaffar’s public career later had ups and downs, as did his relations with the mainstream of the Palestinian national movement. The peak of his popularity came at the time of the mass demonstrations against the Mandate regime in 1933, when many of the protest leaders were arrested. All agreed to post bail except for al-Muzaffar, whom the Palestinian national poet of the time, Ibrahim Tuqan, memorialized in verse:

Palestine in flames, roars in fury

Step aside—you are not my men

The captive [al-Muzaffar] is he who has gained honor

And those who pursue office are his atonement. (Tuqan 1966, 48–49)

Al-Muzaffar shared a prison cell with Abba Ahimeir, chief of Brit HaBiryonim, a cell of radical Jewish nationalists. “As a Zionist of the Nordau-Jabotinsky school, the author of these memoirs had no interest in meeting with Arabs,” Ahimeir wrote in an article he published at the time of al-Muzaffar’s death (Herut, July 1, 1949). But the struggle against the British, even if pursued by both men separately, led them to the same prison cell in downtown Jerusalem’s Russian Compound. “That time spent in the company of Muslim Arabs and Levantine Christians buttressed my negative view of the East,” Ahimeir wrote. He called al-Muzaffar the leader and founder of Islamic extremism in Palestine.

Ahimeir’s conduct in the period leading up to the 1929 riots will be examined below. But here we can see that Ahimeir’s characterization of al-Muzaffar as “extremist” had no foundation. That same Sunday, when the riots began in Jaffa, al-Muzaffar had called on the crowd at the Hasan Beq Mosque not to head to the Jewish neighborhoods. It was the second speech, by Isma‘il Tubasi, that ignited the crowd and persuaded it to take action. Perhaps Tubasi’s collapse during his speech made his appeal more powerful. When he came to his senses, Tubasi repeated his call to attack the Jewish neighborhoods and set out to do so himself. In other words, two opposing views about attacking the Jews were voiced at the same time at the same mosque in Jaffa. Perhaps at that very moment the first sparks of resistance to the mufti’s belligerent strategy appeared in al-Muzaffar’s mind. During World War II, he opposed the mufti’s alliance with Nazi Germany (H. Cohen 2008, 184–85).

Jaffa, Sunday, Early Afternoon

The crowd that had assembled at Hasan Beq set out after Tubasi. The first wave of the attack was repulsed by Officer Riggs and his men, who positioned a machine gun at the corner of HaCarmel Street and fired at the attackers. But they were not deterred, and the gunfire continued. The historical-literary reader put out by the Tel Aviv–Jaffa Municipality includes an account of the events written by a Jewish policeman who was positioned at the end of Herzl Street:

I made out two Arabs armed with rifles appearing from under the orange grove’s barbed-wire fence and aiming their rifles to the right, toward our position. When I saw this I instantly aimed my rifle. A single shot and then another one and I saw one Arab fall. The second had also been hit but still had the strength to drag his friend by the feet into the grove.

I gathered up a group of courageous men and we set out on a counterattack. I was the only one with an English rifle and the few rounds that remained. The others—with pistols. The shooting from the side of the orange grove gradually fell silent. The Arabs must have suffered losses from our counterattack. We were able to advance to Herzl Hill, and I again heard lots of shooting at the hill. I raised my head up and saw, at a distance of 200 meters from me, a car with a group of Haganah members who had returned by this route, stuck in the middle of the Abu Kabir neighborhood’s main road; a few of the passengers had jumped out and began running one by one in our direction. They were heading toward Tel Aviv, to Herzl Street. The first to arrive was Tula Gordon and he called for help. After him came the driver, Verobichek, badly wounded in the head. Not far from him was Feingold’s son, wounded. After them a few others. The last was Binyamin Goldberg. When he was two meters from me a bullet hit his head. His white pith helmet was knocked aside and he fell bleeding into my hands, badly wounded in the head. I fired furiously at the advancing Arabs. . . .

At the same time I noticed that a ladder stood next to a one-story Arab house and that a group of armed Arabs was going up and down it between the grove and the yard of the house. I informed some of my comrades and asked them if they agreed to go there with me. They consented. We broke through the door into the yard with our weapons ready for any surprise. When I went into one of the rooms I heard the voices of people talking. I gave a sign to the guys and we broke into the room. The seven Arabs who were there were armed with pistols and sticks and were lying there surprised. Our desire for vengeance burned within us like fire and was satisfied. I checked the rest of the rooms but they were empty. We closed the door and went out. (Hinkis 1957, 231–32)

The author of this article in the book Yafo is Simha Hinkis.

The house in question was that of the ‘Awn family.

His version of the event: there were seven victims, all of them armed.

When he wrote the piece, he was an official of Tel Aviv municipal government.

Binyamin Goldberg and His Companions

Binyamin Ze’ev Goldberg, who fell bleeding into Hinkis’s arms, was born in 1905. He was the youngest son of Yitzhak Leib Goldberg, a wealthy Zionist activist who had opposed Theodor Herzl’s proposal to establish a temporary Jewish home in East Africa (called the Uganda Plan) and who had been one of the first donors to the Zionist land purchase organization, Keren Kayemet LeYisrael (Jewish National Fund). The senior Goldberg financed the purchase of land throughout Palestine, including an expanse on Mount Scopus, just east of Jerusalem, that belonged to Sir John Gray Hill and on which the Hebrew University was built. He also purchased the land on which Hartuv, a farm village in the Judean Hills, was established; Hartuv was also attacked in 1929. Yitzhak Goldberg owned citrus groves in the area of Ramat Gan, just east of Tel Aviv, and was a cofounder of the daily newspaper Ha’aretz and the Carmel distillery. Hayim Nahman Bialik wrote a poem about him, beginning with the line “May my lot be with you, the humble of the earth, the silent souls” (Gershon Gera identified Goldberg as the subject of the poem in his biography of 1984, HaNadiv HaLo Noda’ [The unknown philanthropist]). Yitzhak’s brother was injured during the 1921 riots and died of his wounds; the brother’s grandson, Dan Tolkovsky, who was eight years old in 1929, later became commander of the Israeli Air Force. Binyamin was twenty-four when he was killed. He had graduated from Tel Aviv’s Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium high school eight years previously and been sent by his father to study mechanical engineering in England. When he returned to Palestine in 1927 he went to work at Haroshet HaEmek, an underground arms factory established by the Zionist Labor Brigade on the western side of the Jezreel Valley that was camouflaged as a repair shop for agricultural machinery. But the factory did not last long, so Binyamin returned to Tel Aviv and joined the Haganah.

On Friday, when the disturbances began, Binyamin Goldberg rode to Jerusalem on his motorcycle to take part in defending Talpiot, an isolated Jewish neighborhood to the south of the Old City that was under attack. On Sunday morning he returned to Tel Aviv and immediately set out to evacuate the Jews trapped in the ethanol factory next to Abu Kabir. It later turned out that this mission had been superfluous, because the British had taken responsibility for rescuing the people in the factory. The residents of Abu Kabir thought that the Haganah contingent had come to kill them, so they took the offensive and killed their presumed assailants. Three other members of the Haganah force who had volunteered for the mission were also killed: Yosef Berkowitz, a customs clerk for the Mandate administration; Moshe Harari-Bloomberg, an actor and musician; and Isaac-Yehoshua Feingold, a founder of the Ariel cigarette factory. According to the page about him on the Defense Ministry’s memorial website, Harari called out to the Arabs who were approaching them: “We mean no harm to you, let us pass.” Goldberg’s last words were: “But the Land of Israel will be ours no matter what” (Gera 1984, 218).

This is the Zionist story in miniature: The Jews arrive in Palestine to save their lives and those of their brethren. They speak to the Arabs in two voices: “We mean no harm to you, let us pass” and “But the Land of Israel will be ours no matter what.”

The next morning, on August 26, at 8:15 a.m., an account of the discovery of the bodies in the ‘Awn home was recorded in the log of the Lod District police headquarters (which was responsible for Tel Aviv and Jaffa as well). An Arab family consisting of three men, one woman, and one child were murdered by Jews and cut to pieces, the log entry states. Immediately afterward is another entry reporting that Be’er Tuvia had been attacked by 2,000 Arabs. The Jews had all taken refuge in a single house, and the entire village was on fire. Trucks needed to be sent to evacuate the inhabitants to Rehovot. Then comes another entry: all the Jewish families in Gaza have been brought to Tel Aviv.

Be’er Tuvia was burned down and later rebuilt. The Jewish community in Gaza was never reestablished. Several Jewish settlements were founded in the Gaza Strip after it was taken by Israel in 1967, but all were evacuated in 2005. That same year the fourth and perhaps fifth generation of Palestinian refugees who left Jaffa in 1948 was growing up, many of them in Gaza.

The members of the ‘Awn family were buried after a medical examination of their remains; the doctors filled out death certificates with details about their wounds. Photocopies of the certificates are on file in the Central Zionist Archives.

The Investigation

The police assumed that the Jews murdered the ‘Awn family. Haganah operatives in Tel Aviv reported the incident by telephone to their counterparts in Jerusalem: “It has not been proven that it was done by Jews. Arab robbers are on the loose and it could be that it was a provocative act by Arabs” (ISA P69776/2). That was the first response, and perhaps the hope, of the Haganah.

The police launched an investigation. Officers went to the site and collected bullet cartridges. Witnesses were questioned. They related that a Jewish policeman had arrived at the house at the head of a group of Jews. The investigation continued in an unambiguous direction. In an interview in the daily newspaper Ma‘ariv some thirty years later, Hinkis recalled:

The next morning the British officer Ricks [the journalist’s misspelling of Riggs] came to me and instructed me to take my rifle and go to the Jaffa police station. There the rifle was taken from me and I was dismissed. I sensed that something was wrong and that the rifle had been taken from me as a court exhibit. Two days later I learned that the Arabs had informed the British that a Jewish policeman had killed the seven [victims found in the house]. A Jew also had a hand in informing about that. In the end they arrested me. For a month and a half I had no respite. Interrogations day and night. I denied everything. In the meantime they organized all the incriminating material against me. . . . The trial was conducted in Jaffa. The Jewish Agency and National Committee provided me with defense counsel. The late Drs. Eliash and Dunkelblum, as well as Olshan, Henigman, and Frankel, may they have long lives. (Yamim VeLeilot supplement, November 12, 1965)

Investigating Magistrate

Rules of procedure established in the wake of the riots called for the suspects to be brought before an investigating magistrate. If the magistrate was persuaded that there was sufficient evidence implicating them in manslaughter or murder, he would send the case to a panel of three British judges. On November 6, 1929, the investigating magistrate decided to indict Hinkis on five counts of murder, the victims being Sheikh ‘Abd al-Gani ‘Awn (about fifty years of age), Ibrahim Khalil ‘Awn (forty), ‘Abd al-Gani ‘Ali Bahalul (fifty), Maryam (forty-five), and Halima (twenty-eight). Hinkis was also charged with the attempted murder of two other victims: a five-year-old boy and a two-month-old baby. They were wounded in the attack and taken to the hospital, where they recovered (the testimony heard by the investigating magistrate can be found in CZA L59/68, 61).

No Children Were Killed

Notwithstanding al-Dabbagh’s account, the initial police report, and Sefer Toldot HaHaganah, no children were killed in the incident. The five-year-old was wounded when a bullet penetrated his left arm and exited from his ankle, damaging his internal organs. He spent forty-three days convalescing in the hospital and was released. The two-month-old baby spent ten days in the hospital. According to the medical report, he had suffered a blow from a blunt instrument to the left side of his head—on his ear, temple, and cheek. In other words, he was apparently beaten or struck, but his skull was not shattered. A third child, nine-year-old ‘Ali, the sheikh’s son, was found unhurt, lying under his mother’s body.

Medical Reports

The public considers such reports to be extremely reliable. Courts generally view them that way as well. Why? Because it is both necessary and convenient to do so. After all, neither the readers of this book nor the judges were present at the site when the incident took place. No one knows for certain who did the killing. No one knows precisely what caused the victims’ wounds. Medical reports imbue with authority the general picture of events that a court must construct in order to reach a judicial decision. The expertise that writing such a report requires and the professional language in which it is couched add to its gravity. In fact, courts often receive contradictory medical reports, one from the defense and another from the prosecution. That did not happen in the case at hand. The reports on the victims of the attack in Jaffa were written by the director of the city’s government hospital, Fuad Dajjani.

Arab (and Jewish) Civil Servants

The fact that the medical reports were written by an Arab doctor does not in and of itself mean they were biased. Arab civil servants coped with conflicting pressures and reacted in different ways. During the riots, some Arab policemen took action against the Arab attackers and in some cases testified against them in police investigations. Other Arab policemen joined the attackers, as in Jaffa in 1921. In one well-known case from 1929, a British officer, Raymond Cafferata, shot an Arab policeman who was trying to rape a Jewish woman in Hebron. In general, the conduct of most Arab policemen can best be described as navigating between a rock and a hard place—they were not overly diligent in thwarting Arab attacks, choosing not to become the targets of ire from their own community, but they also sought to do their duty adequately enough to avoid reprimands from their superiors. The assumption here, which many Zionists disputed, was that the British administration sought to squelch the riots rather than encourage them.