Eden Gebre Egziabher

MAKINA CAFE

25

ERITREA AND ETHIOPIA

Eden was born and raised in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, until age fourteen. She spoke Amharic at school and in public, but with her Eritrean family and neighbors, she spoke Tigrinya. Her mother was an entrepreneur who founded private schools, her father an engineer for Shell Oil Company, and both parents traveled frequently for work.

Eden had lots of friends, both Ethiopian and Eritrean, and her home was often full of guests and relatives visiting from Eritrea. She loved when her cousins would stay with them, sometimes for months on end. They would make all sorts of traditional foods together, sometimes even lasagnas and pastas, a culinary heritage of the Italian colonists of Eritrea. “Aside from the Italian influence on Eritrean cuisine, Eritreans and Ethiopians have a very similar culture and cuisine—the main differences are in language, hairstyles, clothes.”

When the Ethiopian-Eritrean war broke out in 1998, Eritreans residing in Ethiopia, including Eden’s family, were given two weeks to sell everything and leave the country.

Eden’s parents had long been active in the Christian church and had hosted an older American missionary couple in their home in Addis back in the 1970s. So when Eden’s mother got stuck in the US, Eden’s dad called up their old American friends and asked for help. They immediately returned the favor, inviting Eden’s family to come stay with them in Charlotte, North Carolina, where they sponsored them and helped them settle into a new American life.

“We ended up in America as refugees, and many people in the community came together to help our family get on our feet. Seeing people that didn’t know us, who were willing to help us, created something in me. I told myself, One day when I am in the position, I want to be able to give back the same way others did. This journey took over a decade.”

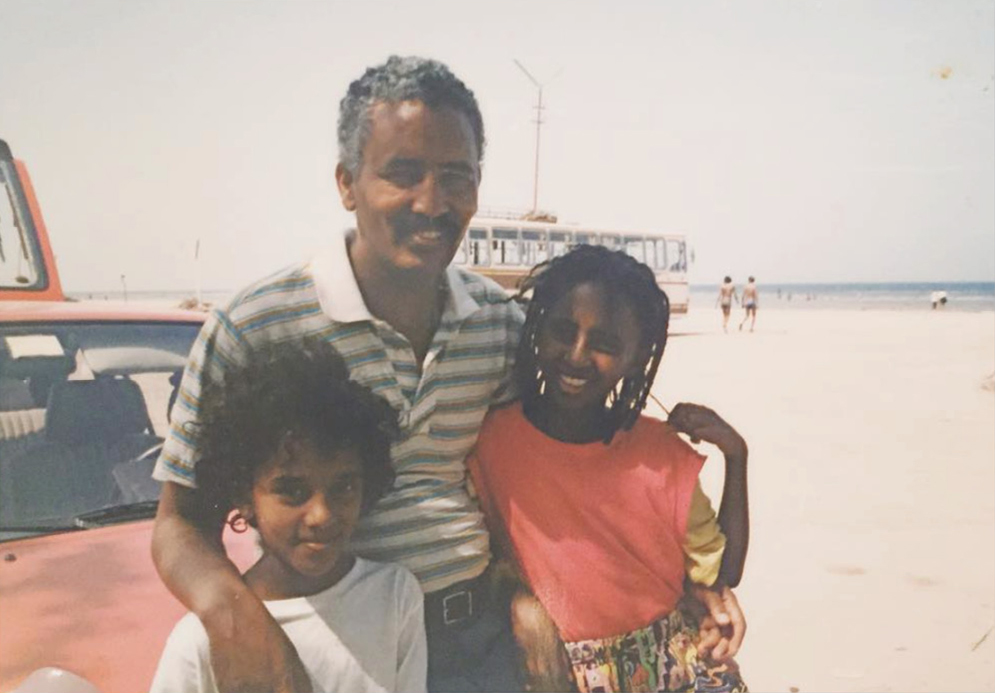

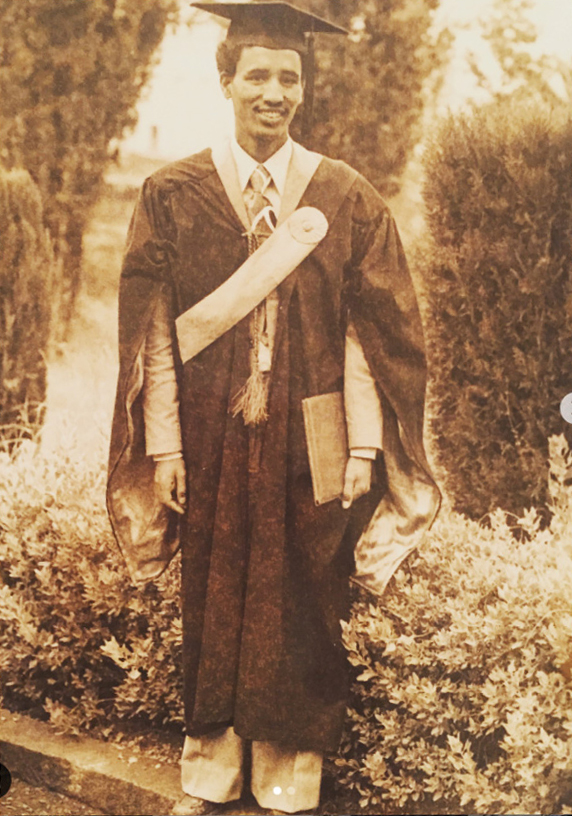

Eden; her father, Gebremeskel; and her sister Emnet vacationing by the Red Sea in Massawa, Eritrea (above); Eden’s father graduating from Addis Ababa University (right)

Going straight into high school in Charlotte was tough for Eden: There were only five non-Americans in her entire school, and she barely spoke English when she arrived. But when her new school took her on a class trip to New York, she saw people “of all colors, from all over the world” and loved it. She decided to someday make it her home, imagining herself working at the UN, fostering international peace, learning from other immigrants and refugees. In the meantime, she worked hard on assimilating into her new environment and mastered English within a year.

“I WANT TO BRING ETHIOPIANS AND ERITREANS IN THE US TOGETHER OVER FOOD TO CELEBRATE THEIR JOINT CULINARY HERITAGE AND APPRECIATE THEIR DIFFERENCES, TOO, LEAVING POLITICS ASIDE.”

In 2016, with an MBA under her belt and a social mission in her heart, she decided to go into the food truck business, with a mission of fostering Ethiopian-Eritrean peace through food. “I want to bring Ethiopians and Eritreans in the US together over food to celebrate their joint culinary heritage and appreciate their differences, too, leaving politics aside.” She also wants to educate Americans, many of whom may not even know that Eritrea exists, let alone that their cuisine is similar to Ethiopian cuisine, with the addition of some Italian influences.

Eden named her food business “Makina” because it sounds like the word for “car” or “truck” (as in “food truck”) in Ethiopian Amharic, in Eritrean Tigrinya, and in Italian. After a few stints at the Queens Night Market, Makina is now a go-to food truck in midtown and downtown Manhattan, and Eden hopes it will grow into a brick-and-mortar restaurant before long, one that will specifically seek to give back and pay forward to Eden’s community, as well as to her new hometown of New York City.

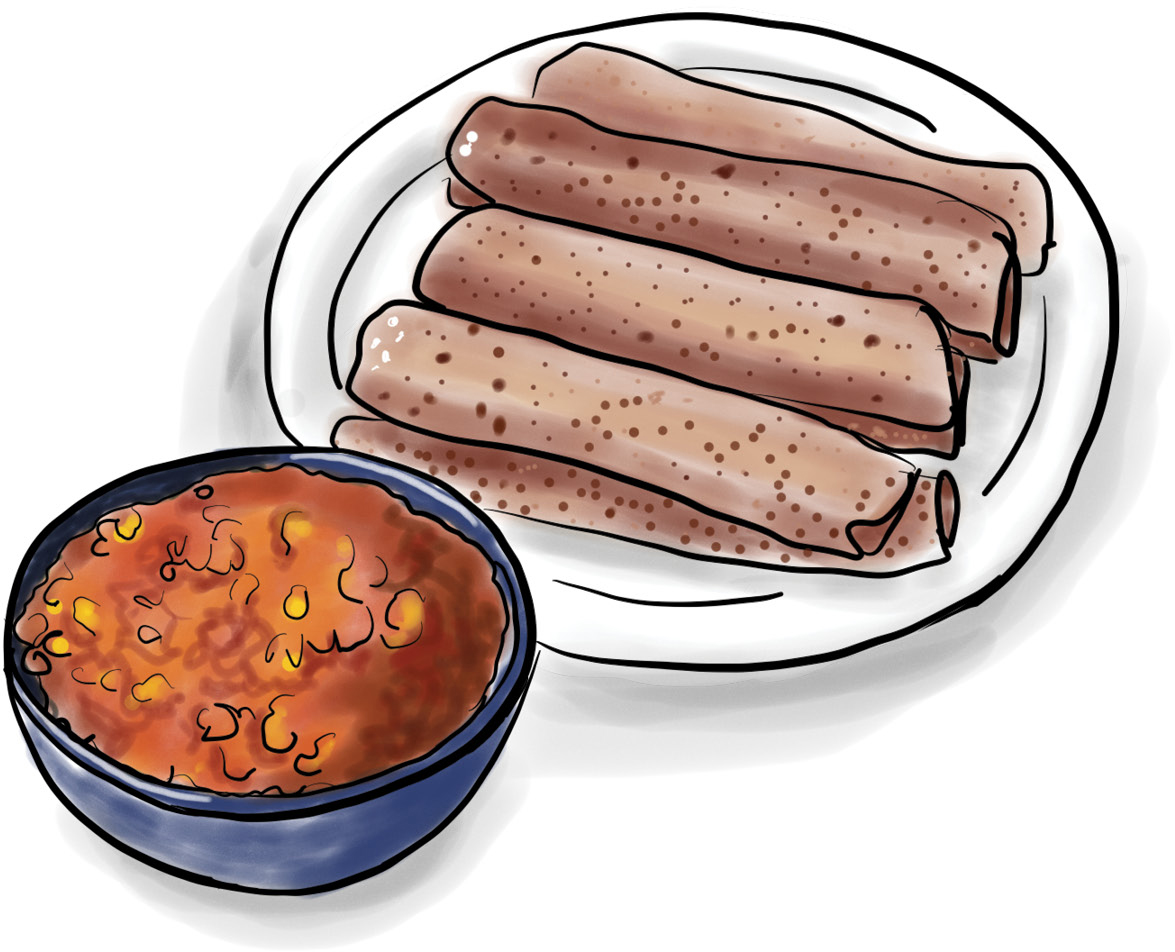

INJERA

WITH SPICY RED LENTILS

Eden says that “injera is our version of rice, so we eat it pretty much with everything.” The moist, fluffy, spongy, versatile flatbread is eaten with hands and used to grab or sop up stir-fries, stews, and other tasty morsels. As a kid, Eden would be allowed to test her hand at making the last batch of injera batter, but it wasn’t until she started Makina Cafe that she really understood all the factors that go into making injera, including temperature, humidity, and amount of water. Spicy red lentils (misir wot) are the quintessential Eritrean vegetarian dish, but you should consider making an array of dishes to go with injera.

Makes 6 servings

INJERA

3 cups (495 g) teff flour

¼ teaspoon active dry yeast

¼ cup (60 g) plain whole-milk yogurt

1 cup (125 g) self-rising flour

MISIR WOT

3 or 4 medium red onions, puréed

1¼ cups (300 ml) vegetable oil

2 tablespoons garlic purée or 6 garlic cloves, peeled and puréed

2 tablespoons ginger purée or one 5-inch (13 cm) piece peeled fresh ginger, puréed

1 tablespoon ground turmeric

¼ cup (65 g) tomato paste

⅔ cup (80 g) berbere

1½ tablespoons salt

1 tablespoon ground black pepper

2 cups (385 g) dried red lentils

3 tablespoons ground cardamom

1. To make the injera, combine 1 cup (165 g) of the teff flour with the yeast and yogurt in a bowl, cover with a light towel or paper towel, and let rest at room temperature for 3 or 4 days, until it rises and the yeast bubbles. (This starter is the most crucial part of making injera. If the yeast is not active, the injera will not come out right.)

2. Combine the self-rising flour with 1 cup (200 g) of the starter and the remaining 2 cups (330 g) teff flour. Add some water, up to 4 cups (960 ml), and mix well until the desired consistency is reached: If you like thick injera, add less water; if you like thin injera, add more. Cover with a paper towel and let rest at room temperature for 12 hours, or until it begins to bubble.

3. Heat a skillet (with a lid) over medium heat, to about 320°F (160°C). The size of the injera will depend on the size of the skillet. Pour some batter into the skillet as you would for a pancake. Cover and cook for 2 or 3 minutes, until the edges start to lift up off the pan surface. Remove and let cool. The cooked injera should have many holes or air pockets and taste like sourdough; if it does not, stop cooking and let the batter sit for longer before trying again.

4. Continue cooking, stacking the injera on top of each other, and let cool. If using immediately, serve when cool enough to handle. If storing them, wrap in plastic wrap to prevent drying out and keep in the refrigerator or freezer. Put them in the microwave or oven to reheat.

5. To make the misir wot, heat the puréed onion in a medium pot over medium-low heat. Let the onion sweat out all the water until the onions are golden, 20 to 30 minutes.

6. Pour in the oil and garlic and cook for 5 to 10 minutes, allowing the garlic to cook. Add the ginger, turmeric, and tomato paste and mix well. Add a splash of water so the bottom doesn’t burn. Cook until the flavors have married, about 10 minutes.

7. Add the berbere, salt, pepper, and a splash of water to prevent the berbere from sticking to the pan, and cook for about 5 minutes while stirring to mix. Be careful not to burn the berbere. Add 7½ cups (1.8 L) water to the pot, cover, and bring to a boil.

8. Meanwhile, rinse the lentils with cold water to remove any dirt.

9. Once the stew is boiling, add the cardamom to the pot and mix well. Add the lentils and cook until softened, about 7 minutes. Turn off the heat, cover the pot, and let rest for at least 20 minutes, allowing the residual heat and steam to finish cooking the lentils.

10. Plate the injera and spoon the lentils over it to serve.