There’s a funny thing about natural history museums on the West Coast. For a place with so much natural history and so many people, museums are few and far between. This is one of the reasons why the fossils of the West Coast are not so well known to residents. Ray and I knew that the way to tell our story was to find experts – both scientists and local collectors – who knew what we wanted to know and to interview them. That modus operandi directed us both to local universities and to the towns where the best fossils were.

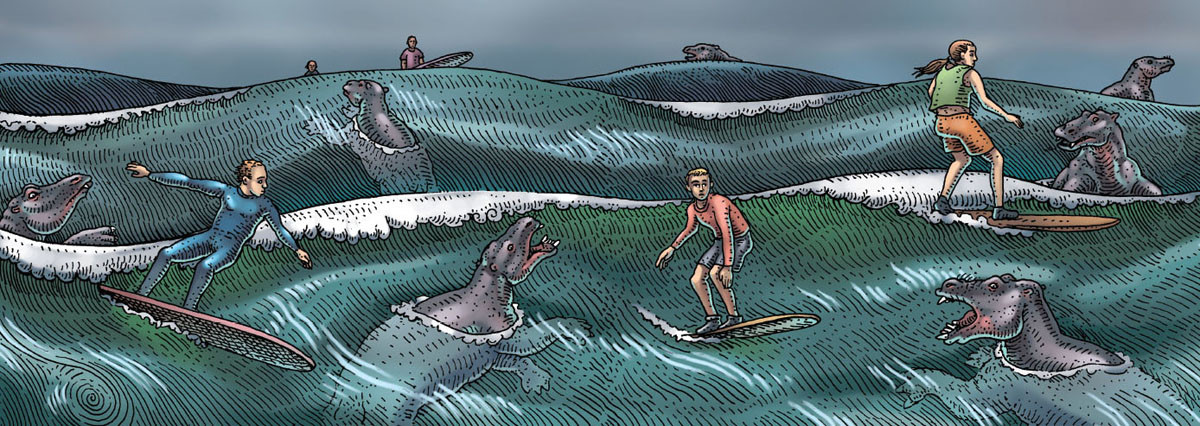

If the desmostylians of the North Pacific had survived to this day, one might have enjoyed a scene like this.

We knew that the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) in Berkeley would be a gold mine for our story and would consume several days of our visit. While most people think museums are places that only exhibit stuff, the reality is more complicated. They’re also places where our culture preserves its treasures and where those treasures are studied. UCMP in Berkeley is an especially interesting case because it has limited public displays – the museum exists primarily to support the students on campus. And Ray and I knew that a whole bunch of secrets were hidden behind those walls.

The history of paleontology at Berkeley is rich, and most West Coast paleontologists have spent time there, either as students, faculty, or visiting scientists. The state of California had an explosive beginning with the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in January of 1848 and the acquisition of California from Mexico in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo just over a week later. Within a year, the gold rush was on and prospectors, miners, and geologists were streaming into the port of San Francisco. By 1850, it was a state, and by 1860, the state had its own geological survey. By 1874, the fossils discovered by the survey were transferred to the young University of California in Berkeley. That same year, the geologist and paleontologist Joseph LeConte, a refugee from post–Civil War South Carolina, became the first professor of paleontology. LeConte was a devotee of Darwin and an ardent spokesman for the concept of evolution, and he became a close friend of John Muir. His 1878 textbook, The Elements of Geology, amply illustrated the fossil record, and he followed that with a popular text aimed at a high school audience in 1888. When I cleaned out my grandparents’ home in Fresno in 1978, I found a copy of that very text. It was clear that LeConte was not opposed to religion, but it was equally clear that he did not see any conflict between evolution and religion.

LeConte hired his student John C. Merriam in 1894, and Berkeley was well on its way to dominance of West Coast paleontology for the next century. Merriam did much of the early research on the La Brea fossils and also ventured north into Oregon to the John Day Fossil Beds (famous for its Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene fossils). Like LeConte, Merriam was a popularizer of ancient life, and in 1915 he published his History of Life on the West Coast.

Paleontology at Berkeley was both aided and impaired by a sugar heiress from Hawaii who had a passion for paleontology, and whose fortune would sustain the growth of the program for nearly half a century. Annie Montague Alexander showed up in Berkeley around 1910 and fell in love with fossils. She would join the paleontologists in the field and enjoyed digging. She was also very wealthy and used her funds to influence the workings of the university, often shaping the hiring and firing of faculty and the directors of departments. During that time, the science of geology and paleontology at Berkeley was fractious on the campus, but it was also vibrant, and the string of names of people who worked and studied there forms a big part of the “Who’s Who” of West Coast paleontology.

In 1926, during one of those chaotic periods, paleobotanist Ralph Chaney arrived on campus and began to research West Coast fossil plants and the origin of modern West Coast vegetation. California has unique and wonderful vegetation – from the bizarre Joshua trees of the Mojave Desert to the giant sequoias of Yosemite to the oak savannahs of Napa to the towering coastal redwoods of the north coast. Chaney wanted to know how that world had formed. He and his students worked their way across the state and up into Oregon, finding layers of fossil leaves, nuts and seeds, and petrified forests, and they began to unravel the history. Chaney learned that the coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) and the giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum) had a rich fossil record. He also found and described many of their extinct fossil relatives.

One of Ralph Chaney’s students, Erling Dorf, became a professor at Princeton, where he taught a student named Leo Hickey, who later became my professor at Yale. While my real great-grandfather was from Sweden, my academic great-grandfather was from Berkeley. In the obscure ways of science and paleontology, things that happened a century ago on college campuses still matter to this day.

By the beginning of the Second World War, Ralph Chaney was considered one of the nation’s premier paleobotanists. In 1941, botanists in central China discovered groves of a tree that looked like a coast redwood but wasn’t. In fact, it turned out to be a living example of one of Ralph’s fossils, and after the war he journeyed to China to see the trees for himself. Indeed, the living trees were identical to his fossil, and in 1948, he named a new species of conifer, Metasequoia glyptostroboides. The publication of his find came just a decade after the discovery of the presumed-extinct coelacanth fish living off the coast of Madagascar, so the world was primed to hear about fossil species being discovered alive in remote parts of the world. Chaney became about as famous as any paleobotanist could be, and he made several trips back to China, returning with seeds of his new “dawn redwood.” Many of these were planted on college campuses and arboreta around the country, and now, in their eighth decade, many of these trees are towering examples of the relationship between living and fossil plants.

Charles Camp, a vertebrate paleontologist interested in Triassic reptiles, arrived on the Berkeley campus in 1922 and became a favorite of Annie Alexander, whose actions got him appointed head of the museum, while Chaney remained the head of the department. Camp went on to excavate a fabulous Triassic ichthyosaur bone bed near Berlin, Nevada. In 1952, he wrote a book called Earth Song: A Prologue to History, in which he used the exquisite pencil drawings of William Gordon Huff – the same WPA artist we met in Chapter 3 – to illustrate the ancient world of the West Coast. Today, this rich history of paleontology continues, and a quick survey of the faculty and staff of the Berkeley museum turned up more than twenty paleontologists. And, importantly, Berkeley is also the home of the National Center for Science Education, a nonprofit group that fights to protect scientists from the attacks of creationists.

I have been corresponding with Berkeley paleobotanists since I was a teenager, and I knew the treasures we would find in Berkeley’s well-curated cabinets. By this time, Ray and I had honed our approach for interviewing paleontologists and extracting their tales. It was interesting for me as an active paleontologist to switch into the role of journalist and to interview my colleagues. There was one story that I especially wanted to hear, so we made an appointment to meet with Bill Clemens, the curator of fossil mammals.

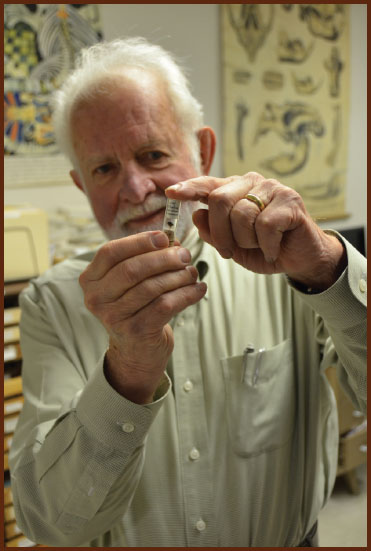

Bill is a warm, avuncular man with white hair and beard and a soothing voice. He made his career studying the tiny mammals that lived with the last dinosaurs and those that survived the extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period. He has mainly worked in the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation of eastern Montana, driving there every summer with teams of students. The fossils he studies are the teeth from animals that were the size of mice. Many of his fossils are as small as sand grains.

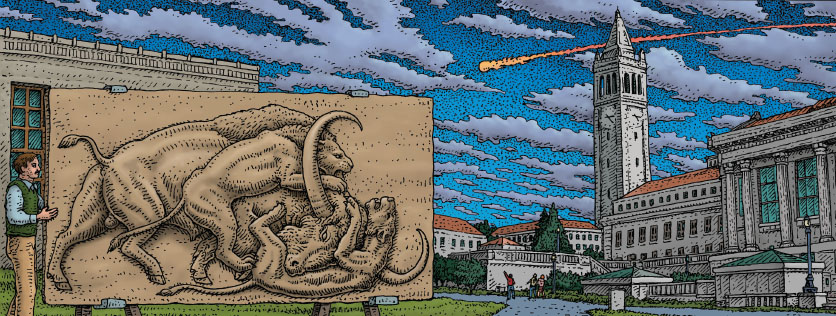

Bill was minding his own business in the late 1970s when a geologist, a physicist, and two chemists from across campus proposed the idea that an asteroid had caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. At the time, Bill probably knew more about the actual fossil record of land animals at the end of the Cretaceous than anyone in the world, and he was surprised to hear their theory. Based on what he knew, he opposed it, suggesting instead that the fossil record showed a gradual rather than catastrophic termination to the Cretaceous. When the team led by Walter Alvarez published their hypothesis in 1980, Bill Clemens rebutted it in print and it was game on.

I had a ringside seat for this fight, as my Yale professor, Leo Hickey, was Bill’s friend and colleague (he was also Walter Alvarez’s Princeton classmate). The conversation got personal when Nobel laureate and physicist Luis Alvarez, Walter’s father, insinuated that paleontologists were not real scientists but were instead little more than “stamp collectors.” The next decade was both exciting and painful, as the scientific and personal conflict waged on. Eventually, the existence of the asteroid impact became impossible to ignore and a general sense that it was the cause of the Cretaceous extinctions came to dominate the scientific community.

Bill Clemens ponders the tooth of a Cretaceous mammal.

By the time Ray and I walked into Bill’s office, thirty years had elapsed and I was really curious to hear how Bill felt about the whole thing now. He welcomed us warmly and graciously answered our questions about his childhood in California. He had gone to high school with William Huff’s daughter and arrived as a student at Berkeley in 1955, just in time to take Ralph Chaney’s last paleobotany class. His love of fossil mammals formed when he visited his grandfather’s ranch near Torrington in southeastern Wyoming and found fossil bones sticking out of the ground. As a student, he learned that it was possible to use a window screen to sort tiny fossil mammal teeth from loose sand, and soon he was on his way to studying the mammals that lived with the last dinosaurs. We discussed his long and productive career and wondered if he had finally warmed to the asteroid extinction theory. His responses suggested that thirty years had not been long enough to convince him and that he was still searching for an alternate explanation for the extinction that was more nuanced than a giant rock from outer space.

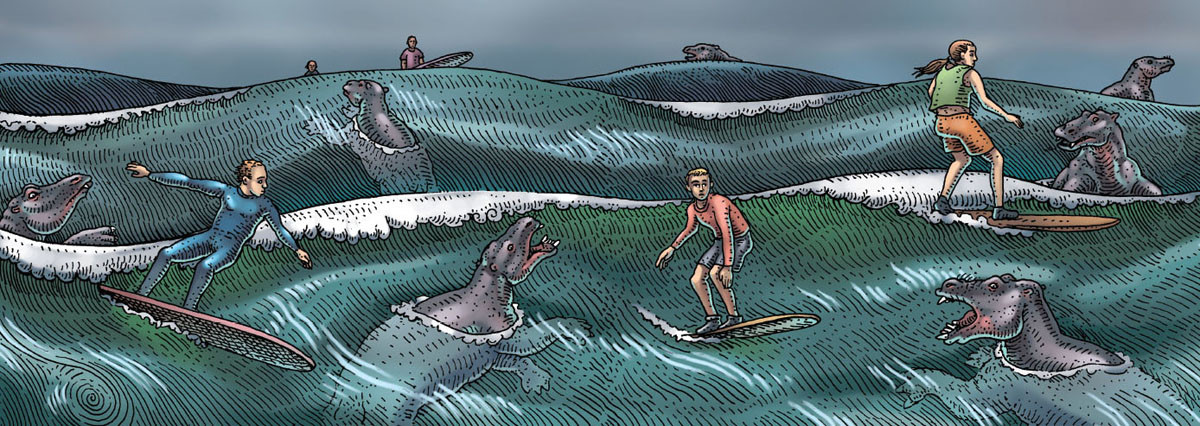

Ray considering his fate as the prey of Panthera atrox, the American lion.

In the summer of 2005, a truck mechanic named Roger Costillo was walking his dog, Jenna, through the middle of downtown San Jose when he – or the dog – spotted a bone sticking out of the bank of the Guadalupe River. It turned out to be a mammoth tusk. The Berkeley crew was called in to investigate, and they excavated a partial skull, a femur, part of the pelvis, pieces of ribs, and several toe bones. The San Jose Children’s Museum suddenly had a mascot mammoth named Lupe. Naturally, we stopped into the museum and visited the skeleton. Because it was a partial skeleton, the bones were displayed in glass cases, and the museum had contracted for a reconstructed skeleton to be mounted within a wire mesh screen to show the shape of the whole animal. One thing that jumped out at me was its incredibly long tail. Outside the museum, there was a complete fleshed-out mammoth, which, apparently, had arrived by helicopter. A dog finds a bone and a helicopter delivers a mammoth. Such is paleontology.

Pivoting away from this tender topic, I directed our line of questioning to the expeditions that Bill had led to the North Slope of Alaska in search of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs. Ray and I hoped to visit these sites ourselves, and we were full of questions about how we might pull it off. Ray is petrified of bears, and Bill didn’t do much to quell his fear. At the time, our Alaska expedition didn’t seem very feasible but, as you will see in Chapter 13, it happened.

We spent a few days in Berkeley, harassing scientists and pulling drawers in the endless collection. The more we looked, the more we realized that the Bay Area was loaded with obscure and little-known fossil sites.

The guys at Berkeley told us a quaint story about a gravel pit near the town of Hayward. In 1940, a few fossil bones were discovered in the pit, and a local high school teacher named Wesley Gordon organized a group of seven-to-thirteen-year-old boys to help him dig out the fossils. The boys got good at collecting the bones and they formed quite a team. Soon they were known as the “Hayward Boy Paleontologists,” and they found enough cool stuff that they were featured in Life Magazine in 1945. They continued working as a group into the 1950s and eventually collected more than 20,000 fossils that included plants, clams, and more than 50 species of animal, including fish, frogs, turtles, rodents, dire wolves, camels, horses, birds, seals, four-horned antelopes (Tetrameryx irvingtonensis), deer, mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, short-faced bears, and saber-toothed cats. In fact, Berkeley paleontologist Don Savage eventually named the Irvingtonian Land Mammal Age (the same age as the fossils from the Fairmead Landfill near Fresno) for the fossils found at this site. Eventually the site was buried under road construction, and today it lies beneath Interstate 680 near Route 238. If you visit the town of Fremont, you’ll find Sabercat Historical Park, created to celebrate this discovery.

Mammoths and mastodons were big animals, and when they died, they often left behind big bones – bones that are hard to miss and even harder to ignore. They pop out of construction sites and stick out of riverbanks and sea cliffs. If you doubt this, just Google “mammoth discovery” and many recent examples will pop up. Because of their size and obviousness, mammoth and mastodon fossils are relatively common discoveries, and if paleontologists are alerted, they can usually find additional bones from smaller and less obvious animals along with them.

We were now headed to Monterey to see a mural that Ray had designed for a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) building at Pacific Grove, and our route took us through Castroville. I have always known Castroville as the Artichoke Capital of the World. I’m a big fan of artichokes, and nostalgia will always bend my coastal drives through Castroville just to see the giant artichoke on Main Street. Had we been there in 1948, we could have seen Marilyn Monroe being crowned as the town’s first honorary Artichoke Queen.

This time, however, we had a different reason for visiting. An artichoke grower named Ryan Jefferson had been working his field when he came across a curious fossil. This next day, his cousin Martin Jefferson identified the fossil as a mammoth tooth. They called nearby Foothill Community College and made contact with an archaeologist named Tim King. The college responded and the web lit up with news about a mammoth in an artichoke field.

I had called ahead, and Tim was waiting for us when we pulled up at the agreed-upon mile marker. He had the excitement of a kid and was eager to show us the site. A team had been digging into the slope and were finding more than mammoth. They had parts of a Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersoni) as well as camel, horse, and mastodon. Tim had his archaeologist glasses on and was eagerly searching for evidence of humans or human activity with these Ice Age bones. I was looking through my geologist sunglasses, and we had a healthy debate about the nature of the site.

Tim King with an artichoke plant and fossil bone in the foreground and a mammoth excavation in the background.

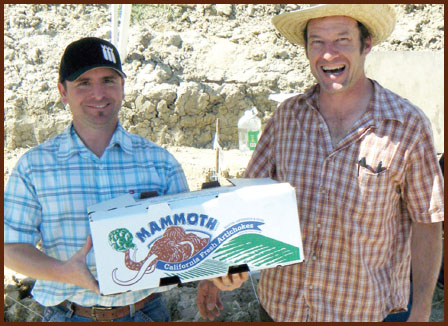

Martin Jefferson and Dan Cearley with a box of Mammoth artichokes.

Ryan Jefferson and a Mammoth Artichoke T-shirt.

The crowd that greeted us included archaeologists, farmers, and La Brea Tar Pit paleontology volunteers from Los Angeles. Martin Jefferson was operating the backhoe and he was seeing more than fossils. He was seeing dollars. He had already created a “Mammoth Artichoke” logo and was printing it on his artichoke crates. He and Ryan were happy to see us and gave us Mammoth Artichoke T-shirts.

It seemed that the dueling bands of Californian paleontologists from San Francisco and Los Angeles might be warring over who got to collect the fossils found in the land between the two cities. One of the guys from Los Angeles was an artist named Josh Ballze who was dressed in black leather with all sorts of fossil tools and cameras strapped to his arms and legs. Jurassic Park, meet Mad Max..

Frankly, by this time we were getting a little weary of mammoths, mastodons, and gomphotheres. It seemed like California was infested with various kinds of fossil elephants. It’s not the first thing that you think of when you think about the Golden State, but it certainly is a fact when you are on, or in, the ground.

We had some genuine West Texas barbecue in Castroville and drove on to Pacific Grove where Ray’s drawings were being displayed in the Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History. This museum opened in 1883, not long after California became a state. Even the Smithsonian, which had opened to the public in 1855, did not open the US National Museum until 1881, and many of the other great museums of the United States were founded in the thirty-year window between 1880 and 1910. It was the golden age of natural history and the peak of hobbyist interest in the natural world. In this time before the invention of cars and planes, everyone had the experience of traveling by horse and buggy (or wagon or stagecoach) and, as a result, knew the anatomy of a horse from firsthand observation. Now we talk about horsepower in reference to engines, forgetting that real horse power is how we used to get around. Back then, there were clubs that collected shells, butterflies, bird eggs, beetles, wildflowers, rocks, fossils, and all sorts of other natural curiosities. There was a deep and pervading belief that nature was worth serious contemplation.

John Muir, the Scottish naturalist, had made his way to California in the late 1860s and was living in Yosemite at the end of that decade. It was his writing and his persuasive promoting of the beautiful valley that eventually drove the US government to designate Yosemite as a state-managed park in 1890. Two years later, Muir worked with Berkeley paleontologist Joseph LeConte and Stanford ichthyologist and paleontologist David Starr Jordan to start the Sierra Club, one of the first environmental protection organizations in the world. Teddy Roosevelt, himself a naturalist and a collector, visited Muir in Yosemite in 1903 and because of this visit, named Yosemite as a National Park in 1906.

The Pacific Grove Museum of Natural History is a sweet little museum that takes you back to a simpler time when beauty and nature were more of a day-to-day avocation for people. Pacific Grove itself sits at the southern edge of Monterey Bay, and its quaint neighborhoods abut rocky headlands in a way that puts residents right next to tide pools. Around the corner, and just to the south, are the seaside village of Carmel, the rocky Point Lobos, and the endless cliffs of Big Sur.

This is holy ground for me. My parents honeymooned in Carmel, and we returned there many times throughout my life. We would walk the sandy beaches and play in the driftwood. The tide pools at Point Lobos are like candy for kids; each one has its own little aquarium world of anemones, crabs, and sculpin. When I was twelve and we were visiting Carmel, I found myself in an amazing rock shop staring at something I had never seen and could not imagine – a perfect foot-long fossil fish on a creamy slab of rock. I know now that the fossil was collected in a quarry in the Fossil Basin of southwestern Wyoming and that its name is Mioplosus. At the time, I could not believe that it was real. I really wanted that fossil badly, but it was quite expensive. I remember a price of $200, an incomprehensible sum. After a lengthy, and I imagine teary, negotiation, my mom actually purchased it for me. Forty-five years later, I still have that fossil, and it makes me think of tide pools, the California coast, and my mother.

For a kid – or anyone – who loves finding things, rough shorelines are an endless treasure trove. It turns out that the shore by the Pacific Grove Museum is no exception. To the south of the museum, along Big Sur, there is even a place called Jade Cove, where pieces of gem-quality jade occasionally wash ashore. While Ray and I were out on the museum’s patio enjoying the reception for his show, I noticed a rock that took my breath away. It was a seal-sized chunk of jade sitting on a pedestal. In that glance, my love of discovery, rocky shorelines, and museums was fused into a single glossy-green, gorgeous rock.

Ray’s show was great. He had drawn a series of images that told the story of Monterey Bay and its everlasting relationship with blue seas and green seas. The blue water is the warm equatorial water that brings tropical fish like tuna, marlin, mackerel, swordfish, moonfish, sharks, anchovies, and sunfish. The green water is the cooler water from the north that brings salmon, sardines, ling cod, rockfish, cabezon, auklets, and sea lions.

Monterey Bay is where the blue water meets the green water, and as a result it is one of the most interesting spots on the entire West Coast. The anchovies bring the whales – humpbacks and even blue whales. Meanwhile, the California gray whales cruise past on their annual migration from Baja California to the Bering Sea. Add to that the fact that the deep-sea Monterey Canyon nearly makes it to the shoreline near Moss Landing, and you have a place where the truly deep Pacific Ocean is remarkably close to the beach where people surf. North, south, green, blue, shallow, and very deep, Monterey is a place where the fish once supported a thriving commercial fishery. Today, however, the Monterey waterfront is dominated by tourists who come to see the Monterey Bay Aquarium – one of the best in the world.

Ray wanders past the tanks behind Ed Ricketts’ Lab in Monterey.

The aquarium first opened to the public in 1984, and it rapidly became one of the most innovative and effective places to understand the ecology of an amazing coastal ecosystem. The water intake pipes from the aquarium reach far out into the bay, and the water that comes into the many tanks is cold, clean, and completely saturated with marine life. Many of the tanks are populated by microscopic marine larvae that treat the aquarium as an extension of their ocean home. Everybody who works at the aquarium seems to be a trained marine biologist, and you can barely buy a T-shirt without learning about the biology of a squid.

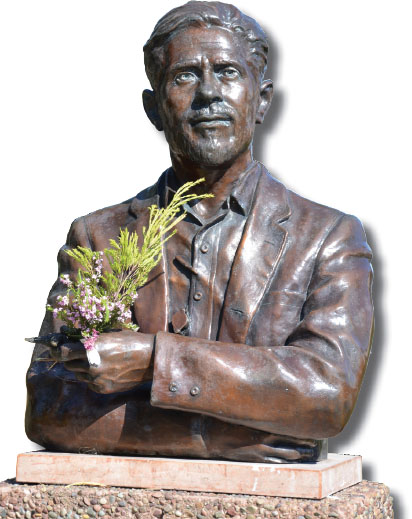

The bronze Ed Ricketts is rarely without fresh flowers.

Ray is a West Coast fish T-shirt guru, and he has had a long relationship with the scientists and aquarists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. His ability to render the denizens of the Pacific depths is matched by their ability to display the real thing to a massive and adoring audience. After leaving Pacific Grove, we wandered around the aquarium enjoying the sharks, herring, and jellyfish and watching the crowds experience the life of the Pacific.

The reason the Monterey Bay Aquarium is such a recent addition is that it is located on a street known as Cannery Row, right on the spot where Knut Hovden opened a sardine cannery in 1916. Monterey was a major fishing port. It was here, in 1970, that I lowered a chopped squid from a dock and caught my first fish. It was also here, in 1973, that the sardine fishery crashed because of overharvesting and ended more than a century of fishing.

The story of this particular fishing port was burned into the American psyche by author John Steinbeck who lived in Pacific Grove in the 1930s and ’40s, and who observed and fictionalized the bustling sardine fishery and the people that populated it. In his 1945 novel Cannery Row, he told the tale of a curious and charismatic marine biologist named Doc who lived on Cannery Row and who was the soul of the community. Doc, it turns out, was a real person and Steinbeck’s best friend, Ed Ricketts. Without formal scientific training, Ed was a different kind of scientist. He made his living by collecting coastal creatures from tide pools, mud flats, and rocky shorelines and selling them to schools and laboratories. His workshop, the Pacific Biological Laboratories, still stands today, at 800 Cannery Row, in the shadow of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Ricketts was one of the first scientists to think in terms of marine ecosystems rather than basic taxonomy, and he was well ahead of his time. In 1939, he and Jack Calvin published Between Pacific Tides: An Account of the Habits and Habitats of Some Five Hundred of the Common Conspicuous Seashore Invertebrates of the Pacific Coast Between Sitka, Alaska, and Northern Mexico. Still in print, and now in its fifth edition, the book is the bible for tide poolers and a testament to the fact that some of the best science comes from the edge of science.

Back in 1940, Ed Ricketts and Steinbeck rented an old sardine boat named the Western Flyer and took a six-week trip from Monterey down the California coast to the tip of the Baja Peninsula and up into the Sea of Cortez. Ostensibly, the goal was to collect specimens for Ricketts’s business, but the resulting book, Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research, coauthored by Steinbeck and Ricketts in 1941, told a much richer tale of friendship and philosophy. In 1932, Ricketts traveled to Sitka, Alaska, and in 1946 he explored the west coast of Vancouver Island and the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii). In 1948, Ricketts was killed when the car he was driving was struck by a train just a few blocks from his lab on Cannery Row. In 1951, Steinbeck published The Log from the Sea of Cortez, an updated story of the 1940 trip without Ricketts as an author and without his long lists of collected specimens. It did include a lengthy preface that was a loving dedication to, and memorial of, Ed Ricketts.

Bobby Boessenecker holding a sea cow bone amidst suburban trash at the site of Repenning’s rookery.

The Log from the Sea of Cortez was very much on our minds when Ray and I were exploring the American West in preparation for our 2007 book, Cruisin’ the Fossil Freeway: An Epoch Tale of a Scientist and an Artist on the Ultimate 5,000-Mile Paleo Road Trip. The idea of an artist and a scientist taking a long fossil-focused road trip was something that seemed right in line with the spirit of the The Log from the Sea of Cortez. And it was Ricketts’s unachieved ambition to visit the entire coast from Baja to Alaska that tossed down a marker that defined the 4,000-mile span of our West Coast fossil journey.

Fossil-studded boulders on the beach at Capitola.

It was with this background that we approached our visit to Monterey. I had contacted Jim Hekkers, the vice president of the Monterey Bay Aquarium and an old friend from Denver. Jim had one thing that we wanted very badly: the key to the Pacific Biological Laboratories. After Ricketts’s death, his lab had changed hands a few times, but its owners had never really scrubbed the place of his presence. It is now owned by the city of Monterey but is not open to the public. It just sits there on Cannery Row, a modest reminder of an amazing man and a different time.

Being in the lab was a moving and memorable experience. It was not just a lab, it was Ricketts’s home, and the trappings of his trade and his habits were still quite visible despite the sixty-two years that had passed since his death. Down the street, next to the railroad crossing that killed him, there is a small bronze bust of Ricketts. Look closely and you can see his bronze hand lens, the sure sign of a biologist or botanist. It is said that there are always fresh flowers in his hands, and it was true for the week we spent in Monterey. We drove out of town with a strong sense that our exploration of the West Coast was well worth pursuing.

I had been searching the internet for interesting individuals who were an active part of the West Coast fossil scene, and one day I came across a blog called The Coastal Paleontologist. Blogs are hit-or-miss operations, but this one was a jackpot. Written by a guy I had never heard of, it was full of facts and useful information, and it was clear that this guy knew what he was talking about. I emailed him and asked if he would mind if an artist and a scientist dropped by for a visit. He agreed, so Ray and I drove to Foster City south of San Francisco and arrived at the home of Bobby Boessenecker. Actually, it was his parents’ home.

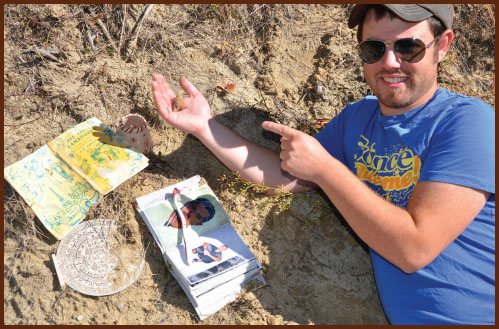

We pulled up to a typical suburban California home and immediately noticed concretions in the garden. Sticking out of the concretions were fossil bones. We were at the right place. Bobby answered the door and welcomed us into a typical living room with atypical contents. Bobby’s dad is a historian and his mom is a judge. Bobby had just spent the previous weekend in a kayak along the coast north of Point Reyes surveying a Pliocene rock layer known as the Purisima Formation. The Pliocene is only 3 to 5 million years old, so you would expect to find fossils of page_69]animals that are pretty similar to those alive today. Much to my delight and amazement, Bobby had found a block of rock with the back side of an imagotarine walrus skull sticking out of it. He told us about a thirteen-year-old kid named Forrest Sheperd who had found a near-perfect skull of this animal in Santa Cruz. Then he showed us a host of treasures that included dolphin skulls and fossil walrus tusks the size and shape of Smilodon sabers. Bobby was just finishing his master’s degree on the Purisima Formation, and he agreed to take us for a drive to see some outcrops and perhaps a fossil or two.

Fossil whale bones.

We took off and headed over to “the 280” (Californians refer to their highways by their numbers) on our way over the Santa Cruz Mountains. I had worked for the US Geological Survey in Menlo Park back in the early 1980s, and this was familiar ground. As we drove past Stanford, Bobby pointed out a gully that had yielded fossil whales and another that was full of fossil barnacles, and he reminded us that Stanford’s first president, David Starr Jordan (co-founder of the Sierra Club), had been an ichthyologist and a fossil shark guy who had worked at Sharktooth Hill back in the 1920s. Then we crossed over the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC), the longest, straightest structure in the world. Built in 1962, this is a 2-mile-long ongoing physics experiment and particle collider. I remembered a story about a skeleton that was discovered during the construction of the facility and called to inquire about visiting hours. They told me that they allowed the public in once a month, but this was not that day. Bobby had also heard about the skeleton but had never been able to see it himself.

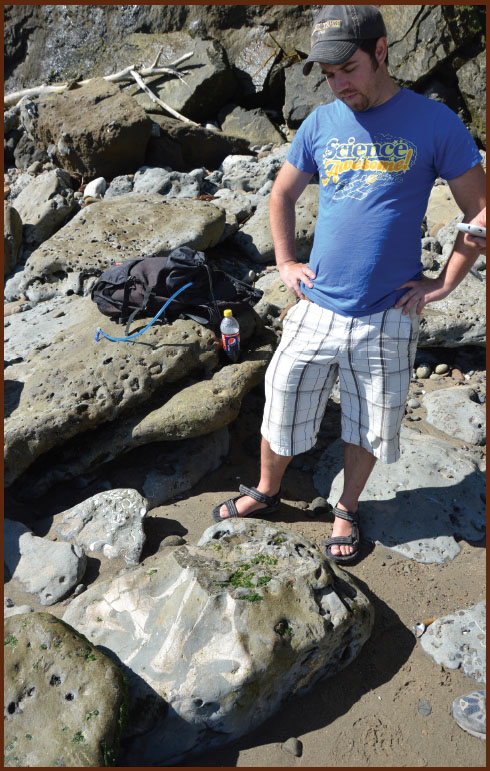

Bobby Boessenecker inspecting a fossil whale skull in a beach boulder.

The surfers oblivious to the fossils at Capitola.

Halfway over the Santa Cruz Mountains, we pulled off at Scott’s Valley and visited forested slopes that contained fossil sand dollars and shark teeth. Driving down a winding forested road, we pulled over to the side and looked at a spot where US Geological Survey paleontologist Charles “Chuck” Repenning had collected parts of several Miocene walruses (Imagotaria downsi). Bobby called it Repenning’s rookery. In a place called Laveage Park, he showed us a spot where Howard University’s fossil sea cow expert Daryl Domning had collected the two fossil sea cows Dusisiren jordani, a mother and a calf that are now on display at the Los Angeles County Museum.

Many of these places were spots where people had found and removed fossils, and there was nothing there for us to see but the sandy outcrop. But in one spot, Bobby showed us a sea cow skeleton still in the bank. It is amazing to realize that these poison oak- and pine-covered hills are actually uplifted Pliocene seafloor.

The next stop was Capitola, a quaint little seaside village just south of Santa Cruz. The main street dead-ended at the ocean, and the town was all bars, surfer shops, and taco shacks. The beach was made of big, flat boulders, and everybody was surfing. It was sunny and breezy and a perfect California day. But it was even more perfect than that. The beach was made of fossils. The boulders were studded with fossil clams so obvious that you would have to be blind to miss them. Bobby pointed out more subtle features like fossil crab claws, and once ours eyes adjusted to the color of the rock, we realized that the boulders also contained huge fossil bones. The waves had rounded the rocks, and because the bone itself was as hard as the rock, it was rounded right along with the rock. We had to look thoughtfully at the smooth surface of the boulders to recognize the embedded bones; these were whale fossils from big whales – baleen whales. The beach was made of fossil whales. And all around us, people were surfing.

Skeleton of the California gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus).

Next, we drove through downtown Santa Cruz, past spots that had yielded fossil walrus and sea cows. We stopped in the Santa Cruz Museum, and sure enough, the place was full of local fossils. Around the corner at the Long Marine Lab there were two mounted whale skeletons, a blue and a gray. Looking at those massive skeletons, it was hard to imagine the work it would take to chop a full fossil whale out of rock. It is said that vertebrate paleontology has two types of fools, those that work on the giant long-necked sauropod dinosaurs and those that work on fossil whales. I actually think the whales might be worse than the dinosaurs.

We bypassed the elephant seal rookeries at Año Nuevo State Park and stopped for dinner and artichoke soup at Duarte’s Tavern in Pescadero. Then we dropped Bobby back in Foster City and headed to Marin County. The next day, I dropped Ray at the San Francisco airport, and he headed back to Alaska. Then my dad picked me up and we headed north to Seattle.

Dad and I drove by way of Calistoga, California, where there is a truly remarkable petrified forest. I have vague memories of visiting this forest when I was a kid, but to see it as a trained paleontologist was something entirely different. Here is a forest that had been blown down and buried by a volcanic eruption about 3.4 million years ago. Entire trees are preserved, but what is truly amazing to me is that this is one of the very few places I have ever seen fossilized bark. Curiously, the fossil forest lies partially buried in a modern forest; huge fossil sequoia and Douglas fir trees lie petrified just below the floor of a living Douglas fir forest. It is one of those very rare places where a fossil site preserves an ancient landscape that is not very different from the landscape that exists today.

It turns out that my real family also has a history with the forest. My dad’s aunt Ethel had lived on a ridgetop in nearby St. Helena, California. She was a devout Seventh Day Adventist who had lived for a while in Hawaii and had a greenhouse full of the most exquisite orchids. By coincidence or design, St. Helena was also the home of Ellen G. White, one of the people who founded the Seventh Day Adventist religion in 1860. A prolific writer, White became the prophetess of the church and the arbiter of its moral framework. She moved to St. Helena in 1900 and died in 1915, so she would not have been there when the petrified forest was discovered, but she would have been aware of it. This was the time when the Seventh Day Adventists were becoming vividly aware of the significance of the fossil record and were struggling to reconcile it with their seven-day version of the Earth’s creation.

Despite the fact that I visited my great-aunt regularly and that she was aware of my burgeoning interest in fossils, she never mentioned the site to me, nor did she take me there. I didn’t think much of this until recently when my second cousin, John Drage, was visiting and recalled his visit to Ethel in the 1970s. He said he had been startled and scared when Ethel, normally a very cautious driver, closed her eyes and hit the accelerator while driving past the Petrified Forest. He realized that she would literally not let herself see evidence of a fossil world that contradicted the world of her Bible. She would not see what she did not believe.

The Calistoga Petrified Forest was discovered in 1870 by a Swedish homesteader who came to be known as “Petrified Charlie.” It was visited that year by O. C. Marsh, the famous Yale paleontologist, who was visiting the Bay Area, and the next year published a paper on the petrified forest. The noted author Robert Louis Stevenson also visited the site and wrote about it in his book The Silverado Squatters. Paleobotanist Ralph Chaney described the site in his research on the origin of redwoods and ended up assigning it to Erling Dorf (my academic grandfather), who wrote part of his PhD about it.

The same cousin related a story of my grandfather Elmer whom he visited in Fresno after hiking the Grand Canyon. John was talking about his hike and going on in some detail. Elmer fell asleep, and John continued talking to my grandmother. At the point in the story where John made it to the bottom of the canyon and saw outcrops of the 1.73-billion-year-old Vishnu Schist, Elmer jolted out of his slumber and roared, “Six Thousand Years!”

My dad had attended the SDA college in nearby Angwin, but he had never visited the fossil forest before. We had a delightful stroll in the fossil forest in the living forest and chatted about the curious coincidence of family history, scientific history, geology, botany and religious dogma.

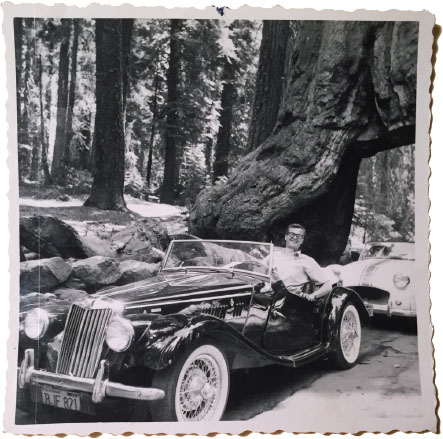

My dad drove his MG TF through a redwood tree in 1955 and we drove through it again in 2010.

Marine shale with the spot where I found my ammonite.

The ammonite in hand.

As we continued through the northern end of California’s Central Valley, I was reminded of the many outcrops of Cretaceous marine shale in the area – outcrops that hold one of the most interesting ammonite faunas in North America. Exposures of 80-million-year-old marine shale are found in central Baja, San Diego, northern California, southern Vancouver Island, and central Alaska. In each one of these places, extraordinarily beautiful ammonites are preserved in concretions that weather out of the shale. The string of sites speaks to the nature of the 80-million-year coastline and the challenges of reconstructing it. In northern California, the presence of booby-trapped marijuana plantations makes it both scary and dangerous to hunt ammonites.

All I could think of was ammonites. We stopped at a roadcut and found that it was made of ma- rine shale. I knew that there would be an ammonite if I looked hard enough, and after thirty minutes of close inspection I finally noticed the edge of sweet 4-inch ammonite poking out of the hill. I didn’t have tools with me so I used a sharp stick to pry the fossil out of the rock. With the ammonite mission accomplished, we continued our trek north.

A year later, I was back in Menlo Park. This time I had taken pains to contact the officials at the Stanford Linear Accelerator to make a better argument about why I should be allowed to visit their well-guarded visitor’s center. I was traveling with Jane Lubchenco, a marine biologist and the head of NOAA who was temporarily based at Stanford. This time, permission was granted, so Jane and I drove to SLAC. We were met by officials who welcomed us into a small building that had exhibits about the construction and scientific successes of the facility. And then, I saw what I had been waiting to see for so many years, the magnificent mounted skeleton of a Neoparadoxia repenningi, a giant extinct desmostylian. Until Larry Barnes had exhibited his Orange County specimen in the new mammal hall that opened at the Los Angeles County Museum in 2010, there was no other skeleton like this on exhibit on the West Coast. This one had been on display since 1998 but only behind a very serious restricted entry gate.

In 1961, Stanford University made a big play in particle physics by approving the construction of the world’s largest linear accelerator. They appointed the distinguished physicist Wolfgang Panofsky, or “Pief” as he was called by his students, as its first director; construction would take five years. In many ways, this was an odd place to build a very long, extremely straight, and perfectly flat building. You might think that the plains of Nebraska would be a better choice, but Stanford is not in Nebraska, it is near the San Andreas Fault and at the edge of the Los Altos Hills. For this reason, the first step of the construction was to dig a very long, very straight trench into the local bedrock. And when you dig into fossil-bearing bedrock, you find fossils. The workers had been encountering shark teeth, whale bones, and parts of porpoises and pinnipeds, but on October 2, 1964, a bulldozer sliced into something amazing: a complete skeleton of something that nobody could recognize. Chuck Repenning was called up the hill from his office in Menlo Park to inspect the site and, recognizing that it was likely some sort of desmostylian, he quickly obtained permission to excavate it. He entrained the aid of a few students and volunteers, including Adele Panofsky, the director’s wife.

In a 1998 article, Adele described the find: “The specimen had been buried lying on its back on the sand of the sea floor. The ribs had fallen to the sides before burial and at least two dozen isolated shark teeth were found in the skeleton or very near to it.” It took the crew six weeks to excavate the skeleton, and by the end of the dig, Adele had found her lifelong obsession.

Over the next twenty-four years, she devoted her free time to cleaning up the fossils, transferring them eventually to the collection at Berkeley, and then devising a way to reconstruct the skeleton and display it at SLAC. She visited museums around the world to interview the few scientists who knew anything about these animals. And she studied the techniques of mounting fossil skeletons. The bones were fragile so she worked with plaster casts rather than trying to mount the actual fossil. Eventually she succeeded, and in 1998, she finished the display, complete with a Miocene marine mural painted by her granddaughter Catherine.

The specimen came to be known as the “Stanford Paleoparadoxia,” and in 2007, Larry Barnes and Daryl Domning officially named it Paleoparadoxia repenningi, or “Repenning’s Old Paradox,” after Chuck Repenning, who had been tragically murdered in Denver in 2005.

I was overjoyed to finally see this hard-to-access fossil display. Jane and I engaged in an animated discussion about its unlikely home and its scientific significance. As the head of NOAA, Jane’s responsibilities included managing the National Marine Mammals Laboratory, and she was thus the highest-ranking marine mammal scientist in the country. And here was a fossil marine mammal from the only major group of marine mammals to have ever become extinct. The desmostylids first appeared around 30 million years ago and became extinct about 10 million years ago. For their 20-million-year turn on Planet Earth, they lived only in the North Pacific, with their range stretching from Baja California to Alaska to central Japan.

Adele Panofsky and her magnum opus, the Neoparadoxia repenningi skeleton mounted in the visitor’s center at the Stanford Linear Accelerator.

While we were engaged, an elderly woman in blue jeans wandered into the visitor’s center, and our hosts introduced us to Adele Panofsky. Never in 20 million years had I expected her to show up, but the SLAC staff had warned her of our arrival, and here she was. She is truly a desmostylid-obsessed woman, and she was so excited to tell us the story of discovery and resurrection. Her hands had grown quite arthritic, and she was proud to show us that her fingers were like those of her fossil. That visit happened in June of 2013, and three months later, Larry Barnes published another paper that compared Adele’s fossil to the Orange County one in Los Angeles and adjusted the name to Neoparadoxia repenningi, or “Repenning’s New Paradox.”

In the time since our visit, Adele’s Neoparadoxia has been dismantled, and there are plans to mount it in a new museum in San Mateo where it will be more accessible to the public. Slowly but surely, our beloved desmostylians are creeping into the public eye.