Sometime late in October of 1961, the November issue of National Geographic landed in our mailbox in Seattle. I don’t remember that moment because I was only thirteen months old at the time, but that event was to have a significant impact on my life. Fortunately for me, my parents, and everyone we knew, held on to their National Geographic magazines, filing them in stacks and shelves because they were different from other magazines. Sometime around four years later, I began to mine the yellow trove, flipping the pages and gawking at the pictures. I don’t remember how old I was when I first dug into the October 1961 issue, but I can sure remember doing it. On pages 718–719, there were three pictures that burned holes in my brain. The first one showed a kid … who looked like me … peering across a rock … watching a guy named Douglas Emlong … who looked like James Dean chipping away at a fossil scallop shell with a rock hammer and a center punch at a place called Moolack Beach in Oregon. The second image was the toothy snout of a fossil sea lion smiling at me out of a rock. The third thing was something beautiful that I had never seen or imagined before. It was labeled as the tooth of a sea cow, but I now know that it was a Desmostylus tooth. I wanted to be that guy. I wanted to find those fossils. And I really wanted that Desmostylus tooth.

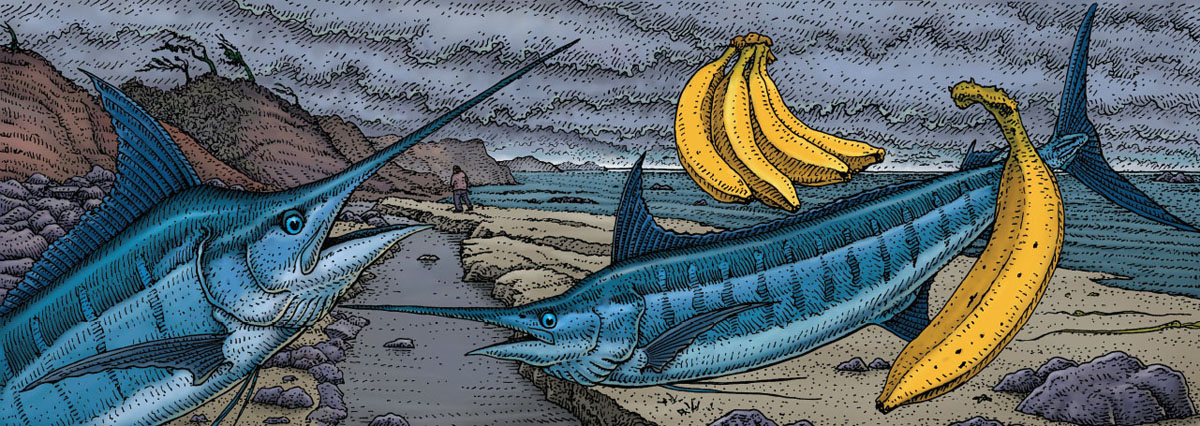

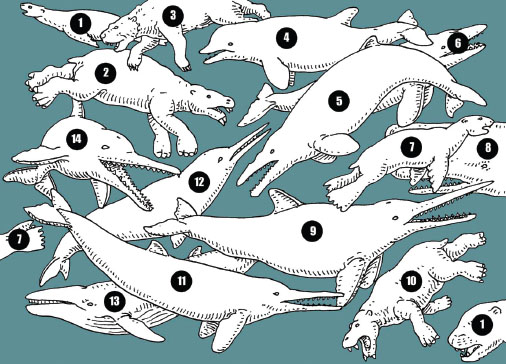

A pair of 20-million-year-old marlin and a bunch of bananas frame a lone fossil hunter on the stormy Oregon coast.

The article was a travel piece about the Oregon coast, and I remembered being very annoyed that the whole article wasn’t about the fossils of the Oregon coast. Fortunately for me, we lived in Seattle and my grandparents lived in California, and my parents liked driving between the two places along the coastal route. So, it wasn’t long after I read the article that we were driving through Lincoln City, Oregon, headed south. I had done my homework and knew that we were approaching Moolack Beach. It was a sunny day, and it was easy to convince my mom to give me a thirty-minute fossil break. She pulled over to the side of the road and turned me loose. She and my sister stayed in the car.

I scrambled down a short, steep, muddy trail to the beach. The sandy beach was backed by a series of small crumbling headlands, and I wandered into a field of engine-sized freshly fallen boulders. Fossils were everywhere. Each boulder was speckled with the cross sections of clams, and in many places, the clams themselves stuck out of the rock, just like ripe apricots waiting to be picked. I could not believe how easy it was. I quickly filled a bag with choice specimens, then dumped it out and started again. You hear about the kid in a candy store, but how often do you see the kid behind the counter at a candy store?

A young Paul Zahl watching Doug Emlong chip a fossil scallop shell from the rock in a picture from the November 1961 issue of National Geographic.

Image courtesy of National Geographic

It was funny, but the euphoric feeling faded quickly because I was not finding any fossil sea lions or Desmostylus. I was no Doug Emlong. I climbed back up the bank and we carried on toward California.

A few years later, when I was a junior member of the Bellevue Rock Club, I met a woman named Jane Cushing who said that she had found some skulls on the Oregon coast. I kept bugging her to show them to me, and she finally agreed to bring them over to my house. Jane was in her late fifties, and my memory of her today makes me think of Bart Simpson’s blue-haired aunts. She pulled her 1968 Chrysler into my driveway, and I ran out to meet her. She lit up a cigarette and opened her trunk.

There, lying on a blanket, were six round rocks, each the size of a large, slightly flattened grapefruit. At first, I thought that Jane was crazy and that she had mistaken round rocks for fossil skulls. People do that more often than you might expect. As I looked more closely, I realized that she had something truly amazing. Each rock was, in fact, a skull.

Imagine that a marine mammal dies and sinks to the bottom of the sea. Crabs, amphipods, and microbes quickly consume the skin and flesh, and eventually the skull is buried in seafloor mud. Over time, the mud hardens to bedrock, and something about the chemistry of the rotting skull causes the mud that infills it to become even harder than the surrounding mudstone. Then the bedrock is uplifted into the surf zone where waves attack it and break it into blocks that tumble in the surf and become round beach boulders. The boulders that are cored by skulls are tougher, and they last longer in the smashing surf. Eventually, the skull begins to peek out of the boulder. The snout, eye sockets, and skull crest come into view. Waves exhume the long dead of the Pacific, cast them on the shoreline, and literally buff them into the here and now where anyone can come along and find them if they have a well-tuned search image.

Kent Gibson doing what he does every morning, scanning the beach for freshly exposed fossils.

That was the last time that I ever saw Jane, and I’ve often pondered what happened to those skulls and what it was that inclined a chain-smoking, middle-aged woman to take the time to share her fossil finds with an eleven-year-old kid. And now I think I know. Fossils are a window into a magical world that just happens to be real.

Portland has never had a natural history museum, but the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) has supported paleontology in a variety of ways, the most important one being that they have run a paleontology field camp at Camp Hancock in central Oregon since 1951. In fact, I know of a surprising number of professional paleontologists who experienced their first wild-caught fossil at Camp Hancock. The camp is named for Alonzo “Lon” Hancock, a Portland mailman who became obsessed with the fossils of central Oregon in 1931 and led both professionals and kids to his various discoveries. He built an impressive home museum that delighted neighborhood kids and visiting professionals. When he passed away in 1961, he left more than 10,000 specimens to OMSI, and they named the camp for him.

Forty years later, in February of 2012, I landed at the Portland airport to meet Ray and begin our tour of Oregon. As I walked off the plane, there was a guy with long blond hair, a well-trimmed beard, and a biblical robe who looked exactly like a 1950s Jesus playing an amplified violin in the concourse and flooding out the loudspeakers with insanely loud new age music. A lone woman was sitting cross-legged and meditating in front of him. There was a card table full of CDs for sale. I tweeted, “Just landed in Portlandia” and received the immediate response, “Put a bird on it.”

This city at the mouth of the Willamette River has ever been the kid sister to Seattle but now is awash in hipsters and is pushing out its own vibe. Oregon, on the other hand, is a largely rural state with huge expanses of sparely inhabited mountains, deserts, and a fantastically accessible coastline. Highway 101 runs faithfully along the Pacific Coast for its entire 300-mile shoreline.

Ray had rented a car for the curiously low price of $7 a day, and we headed off to our destination, the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology in Otis, Oregon (more about this in a moment). This seemed like the perfect place from which to base our excursions. It was pouring rain and the traffic was awful as we slowly crept through Tigard (home of MacKenzie Smith, the middle schooler who led the successful campaign to designate Metasequoia as the Oregon State Fossil) and McMinnville (home of the McMinnville Mammoth site and the Yamhill River Pleistocene Project) before the traffic let up, and we were able to cross the Coast Range on Highway 18 and arrive in Otis, a tiny four-building town just north of Lincoln City, where we had a dinner appointment with Frank and Jane Boyden, the founders of the Sitka Center. Both their home and the Center are located in the valley of the Salmon River just upstream from where it flows along the southern edge of Cascade Head and into the Pacific.

Sea stacks on the Oregon Coast

The Oregon coast is characterized by layers of durable volcanic rock that weather to form prominent rocky hills called headlands. Sometimes these hills are isolated from the mainland by coastal erosion and become sea stacks – some of the most famous sea stacks are found near Cannon Beach to the north. The land between the headlands is usually underlain by softer sedimentary rocks that weather much more rapidly, so a drive along the Oregon coast involves a lot of ups and downs. The view of the coast from the ocean is one of massive headlands separated by long, sandy beaches.

Most of the volcanic rock erupted sometime in the last 40 million years or so, and that gives a decent sense of the age of the interbedded sedimentary rocks as well. When liquid rock, called magma, erupts, it often releases gases that get trapped as bubbles within the magma. When the magma cools to rock, the bubbles are preserved as little round holes called vesicles. Sometimes the vesicles fill with mineral-laden water that precipitates silica in the holes, and, when translucent, this silica is commonly called agate. As the waves wash away the headlands, they also release the agates, which get tumbled and polished in the surf where they are eagerly sought by rock hounds. Because of its long history of volcanoes, Oregon is the most agate-rich state in the nation.

In addition to the agates, beachcombers also search for round glass fishing floats that have washed across the Pacific from Japan, cool pieces of driftwood, and whatever interesting flotsam or jetsam might wash ashore.

Every once in a while, a big dead whale will wash ashore and amuse the local residents until they realize that the smell will persist and grow infinitely worse. In November of 1970, the Oregon Highway Division tried to get rid of a whale that had washed ashore in Florence by blowing it up with dynamite. But, they used too much dynamite, and the resulting blast blew large chunks of blubber through the air. Mattress-sized chunks of blubber rained down on a nearby parking lot where several cars, including those of the guys who placed the explosives, were partially crushed by falling pieces of rotten whale.

Lewis and Clark overwintered on the Oregon coast in 1805–1806 and were so starved for food that they harvested parts of stranded whale for food. Whales and other marine mammals have been washing ashore or simply dying and sinking to the seafloor for as long as there have been marine mammals, and some of these animals have become fossils that are now weathering out of the modern-day shoreline.

We were finally nearing the spot where Doug Emlong had grown up and beckoned to me from the sunny pages of National Geographic, and I now had the opportunity to bring my childhood Desmostylus dreams to life. When Ray and I were in Los Angeles, we had quizzed Larry Barnes about Emlong. He had known him well, and his recollections painted a different image from the one I had constructed from my childhood memories.

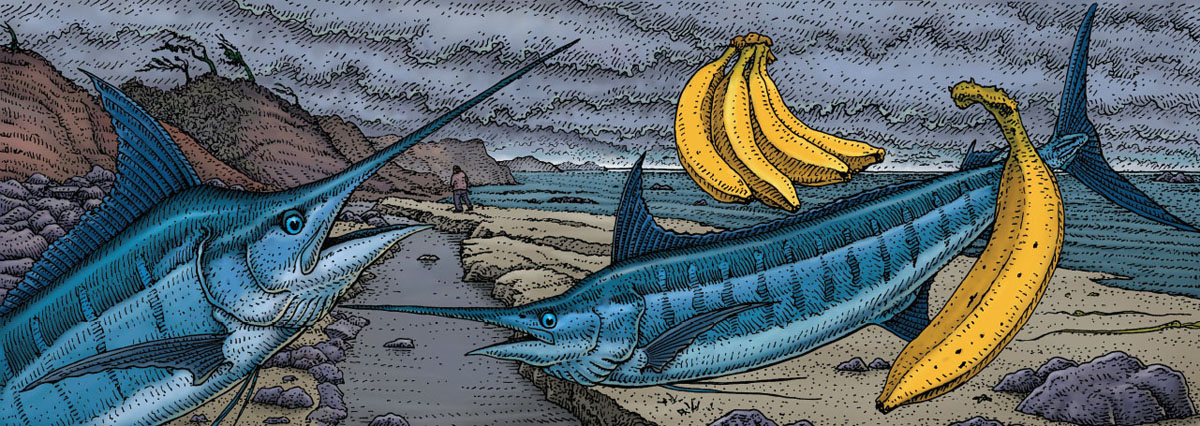

Doug Emlong was born in 1942 and grew to be a curious and artistic kid in Lincoln City, where he learned early how to find agates, glass floats, and fossils on the nearby beaches. By the time he was in high school, he was finding significant marine mammal fossils. He was only twenty when he was featured in the 1961 National Geographic. From 1961 to 1967, he ran a small rock shop/art gallery/fossil museum called the Graveyard of the Pacific in Gleneden Beach where he sold agates, fossils, and his original paintings.

In 1968, Emlong started corresponding with Clayton Ray, the curator of fossil marine mammals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and the two formed a friendship. Eventually, Clayton Ray started helping Emlong pursue the science of his discoveries and began scraping money together to support his efforts.

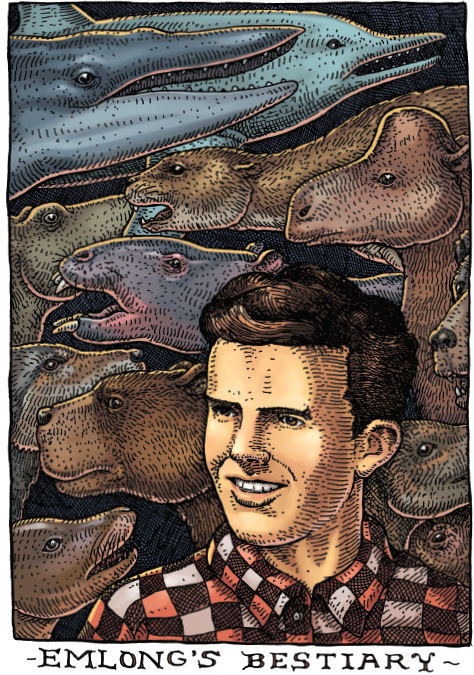

As a collector, Emlong was relentless, scouring the Oregon coast in the worst weather for new discoveries. Eventually he traveled to Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, and California in search of fossils. With whales, pinnipeds, walrus, sea birds, desmostylians and many other marine organisms, the Emlong Collection at the Smithsonian is truly magnificent and is still being studied today. In 2007, Daryl Domning wrote, “Douglas Emlong’s Promethean prowess in discovery of unprecedented vertebrate fossils, alike in beds where many, few, or no collectors preceded him, is well known to specialists having personal knowledge of his activities.” In 1980, at the age of thirty-eight, Emlong fell off of a sea cliff at Otter Crest Loop and died. The police report of the incident suggested that it was not an accident. This much I knew from reading the newspaper clippings and perusing the archives at the Smithsonian.

Barnes described Emlong as a troubled loner who had few friends and who wore magnets in his clothing to help him find fossils. Larry showed us one of Emlong’s most curious discoveries, a complete and nearly perfect skull of Kolponomos newportensis, the oyster bear. This beast lived 20 million years ago, and Emlong had found its fossils in both Oregon and Washington. Larry described the long-fingered bear as a “beach groveler.” The evolutionary history of sea lions is still being written, and one of the closest living groups to the sea lions are the bears. There is still some debate about whether Emlong’s oyster bear is actually a bear.

Frank Boyden happily displaying his spiral coprolite.

We hoped to meet people who had known Emlong so they could help us piece together the story of his short but amazing life; Ray was hoping that we could locate some of his artwork. We arrived at Frank and Jane’s just in time for a perfect meal of local wild mushrooms, lightly smoked black cod from Gold Beach, and fresh king salmon from the Salmon River. Frank served it up slowly over three hours, and we oriented ourselves to our new base where we would spend the next few weeks, venturing out in all directions to sleuth out Oregon’s coastal fossils. The Boydens founded the Sitka Center in 1970 as a place for scientists and artists to come together in the natural beauty of the Salmon River Valley. So here Ray and I were, coming together. Frank had met Emlong once and found him to be a bit odd and very shy with a propensity to mumble.

The next morning, we went to the Otis Café for breakfast. This snug wallet of a place only has four booths, six counter seats, and one table, but the food is amazing. They have homemade pies and black bread, either of which could kill you if you didn’t have the discipline to stop eating. I nearly perished on a couple of occasions over the next few weeks. Ray struck up a conversation with the waitress and rapidly got around to asking her if she had ever met a guy named Doug Emlong. Amazingly, she had a friend who had dated him. Her memory was that he was a science nerd who was picked on in school. When the National Geographic article came out, he became famous – at least locally.

Frank had suggested that if Ray and I were to give a public talk about our book project, we might draw some old rock hounds out of hiding. The Sitka Center staff had found a big room at the Surftides hotel in Lincoln City and posted signs around town for a few weeks before our arrival. Interestingly, Doug Emlong’s mom had once worked at the hotel’s gift shop. On the appointed day, we arrived around noon and were stunned to find the room packed with more than 200 people who were eager to hear us talk about fossils. Bobby Boessenecker and his wife, Sarah, had driven up from Foster City. There was also a group of fossil collectors from an Oregon-based group called NARG (short for the perhaps too ambitious name of North American Research Group) that was founded in 2004 to support Oregon paleontology. They had recently collected a large fossil whale and were chipping it out of the matrix in one of their garages. They called it Wally the Garage Whale. The room was full of fossil-loving people, beach combers, and Ray’s loyal following of T-shirt fans.

By this time, we were three years into our travels, and we were able to show lots of photos and Ray’s art that illustrated what we had been finding up and down the coast. After the talk, a lot of people stuck around to ask questions and to show us fossils. We even met a woman who had graduated from high school with Emlong.

A pair of desmostylid molars.

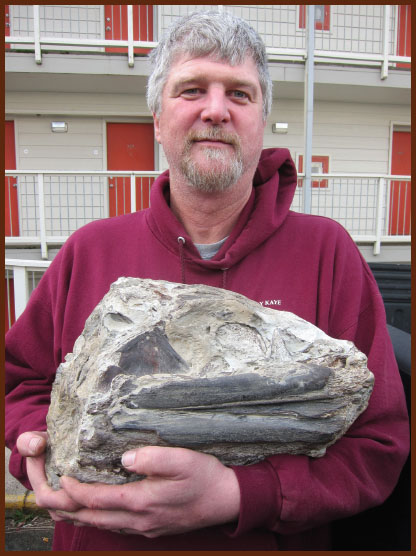

Kent Gibson and his fossil marlin skull.

Eocene crab Pulalius vulgaris from the Gary Eichorn collection.

As the crowd started to thin, a tall, tough-looking taciturn guy in a fisherman’s hoody and rubber boots named Kent Gibson invited us out to his truck to look at a few rocks. He opened up the back door on his club cab and reached for some plastic buckets full of rocks. The first thing he handed me was a concretion with a very perfect skull of a sea lion–like mammal. Hello, Jane Cushing! The next rock had the back half of a whale skull. The third rock was a very beautiful juvenile Desmostylus skull. Hello, Doug Emlong! This was too good to be true and almost too easy. Then he said, “Wait until you see this,” and dropped his tailgate to expose a rock the size of watermelon that probably weighed 45 pounds. “What do you think this is?” In a glance, I could tell that it was a skull, but it was no marine mammal. It was clearly a fish skull, and a big one at that. After some closer inspection, we convinced ourselves that it was a fossil marlin.

We invited Kent, the Boesseneckers, and the NARG guys to a nearby brewpub so we could talk fossils. I was seated across the table from a guy named Bruce Thiel, and, after the first beer, he pulled three amazing fossils out of his pocket. Each was a nearly perfect crab, complete with every single leg and claw, and each was in a small concretion just barely larger than the crab. I had seen fossil crabs before, but I had never seen them this well prepared. Bruce collected the nodules in the creek beds of northwestern Oregon and then painstakingly exposed each crab with a tiny air scribe, a tool that is essentially a jackhammer the size of a ballpoint pen. It is extremely exacting work, and Bruce had raised it to an art form. When I stopped by his home in Portland later in the year, Bruce showed me some of the most amazing fossil crabs I had ever seen. The NARG folks were a diverse bunch, but they all shared our love of fossils and it was like a happy high school reunion.

Portland-based crab-cleaning virtuoso Bruce Thiel and an exquisite Pulalius vulgaris.

A fine trio of crab concretions.

After the NARG guys headed back toward Portland, the rest of us decided that we would try to find the spot where Doug Emlong ended his life. We were joined by Alex Krupkin, a NOAA guy who had been at the talk and who was pretty sure that he knew the spot. He brought a bottle of gin. It was around 4 p.m. in February and blustery. A brilliant sun was setting over a rough and stormy Pacific as we slowly drove up the Otter Rock Loop Road. I had seen the police report from 1980, so I knew what I was looking for and we quickly found the spot. We toasted this sad and brilliant man who had done so much in such a short time to help all of us understand the evolution of marine mammals on the Pacific Coast. Emlong left a significant legacy in all the fossils he had found and sent to the National Museum of Natural History. Living in Lincoln City, he had ready access to the entire coast, and he spent a huge amount of time exploring sea cliffs, beaches, roadcuts, and river cuts looking for fossils. He really had an amazing eye, tireless persistence, and an uncanny sense of where to look.

The next day, we drove south along the coast and made the obligatory stop at the Oregon Coast Aquarium at Newport. My family and I had visited the aquarium in 1997 to see the traveling exhibition that the California Academy of Sciences had built based on Ray’s 1994 book with author Brad Matsen called Planet Ocean. The exhibition was fantastic and further convinced me that I really needed to work with Ray. Back then, Keiko the Orca, star of the Free Willy movie, was being held in a huge tank while waiting to be transferred to Iceland to be released back into the wild. I remember watching this magnificent beast watch me. It scared me. It also completely convinced me that whales of any size should never be in captivity.

Bill Orr ponders a desmostylian snout.

On this visit, and because Ray is fish royalty, we got to see the back of the house, where we were grappled by an octopus and kissed by a sea lion. I noticed the beautiful cast bronze sculptures that graced the entry to the aquarium, and Ray reminded me that they were the work of Frank Boyden.

We also stopped by the Hatfield Marine Science Center, an educational facility named for Oregon senator Mark Hatfield that has been open since 1965. Every February, the Center holds a one-day Fossil Festival where local collectors display their finds and a variety of experts give lectures. I had visited a few times and had the pleasure of meeting Bill Orr who, with his wife, Elizabeth, has written a steady stream of books about the geology and paleontology of Oregon. For a state with no big natural history museum, Bill Orr has served as a one-man reference for the state’s fossils.

Next, we headed south to visit a series of Doug Emlong’s fossil sites. We stopped at Seal Rock State Park where he had exploited the sand-stripping power of winter storms to discover several important fossils representing four different extinct marine mammal species. He found fossils of two kinds of desmostylians: the first was the jaw of Behemotops emlongi, a primitive species that was named in his honor, and the second, Cornwallius sookensis was represented by two exquisitely complete skulls. He also found the bones of a very primitive sea lion, Enaliarctos. But the big find at the site was a complete skull of a whale that was very near the evolutionary split between toothed whales and baleen whales. Emlong himself wrote the first scientific description of this animal, naming it Aetiocetus cotylalveus.

The tide was going out when we got to Seal Rock, and the beach was covered with people walking the edge of the retreating surf in search of agates. The weather was fine, but there had been a huge storm the previous week and the beach was strewn with the carcasses of sea birds that had not survived. We found four cormorants, six rhinoceros auklets, and two tufted puffins, all reminders that life in the ocean is not easy and that any living thing is a potential fossil. That having been said, we did not find a single fossil. Emlong really was good at finding things where everyone else could not.

We didn’t find any agates either, which says another thing about the Oregon coast. A lot of people are walking these beaches and picking them over pretty thoroughly. The old-timers talk about bringing back buckets of agates. Today, you have to wake early and get out there after a big storm to find agates, and the same thing is true for fossils.

South of Florence, we stopped in at the world famous Sea Lion Caves, one of the most genuine tourist spots on the West Coast. Privately owned since 1932, this cave system in a volcanic headland is an underground sea lion rookery. It was raining pretty hard when we arrived, and we entered through the gift shop and walked down a wet concrete ramp to an elevator that took us 200 feet down through the basalt headland and into the Earth. We emerged in a wet rock tunnel and walked to the underground viewpoint.

One of the incredible things about the Oregon coast is the direct adjacency of living marine mammals and their fossil ancestors. The lava that made this cavern cooled about 25 million years ago, and the first true pinnipeds evolved around 26 million years ago. Geology and biology have been dancing with each other since shortly after the formation of Planet Earth. Outcrops and fossils are the memory of that long and ever-changing party.

I remember this place well from my childhood as it was a mandatory stop on our way to California. The cave is large, more than 120 feet tall and quite extensive. It is open to the ocean and waves crash in with a vengeance. And the place is stuffed with sea lions, mainly the large Steller sea lion but occasionally also the smaller California sea lion. The cavern echoes with the braying barks of the 350-pound bulls. It is a mysterious and magical place.

At Coos Bay, we passed the enticingly named Fossil Point where, in 1907, Smithsonian paleontologist Frederick True discovered a partial skull of a truly massive walrus that he named Pontolis magnus. Emlong worked this area hard, collecting remains of a large baleen whale and four different kinds of giant extinct walrus, at least two of them still unnamed. We said our good-byes to the Boesseneckers as they headed south the California. We turned around headed back up the coast.

That night, we reunited with Kent Gibson at his home for dinner, where we met his wife, Lucy, and daughter, McKenzie. They lived up a narrow valley behind a water treatment plant and only a few miles from Moolack Beach. After breaking his back in a fall on a king crab boat in the Bering Sea in 1985, Kent decided to take a less “deadly-catch” job and started working for the Port of Newport.

Some years back, Kent bought a black Lab and named him Bart. Bart was one of those crazy black Labs that preferred to retrieve rocks rather than balls. In 1996, Kent and Bart were walking on Ona Beach, with Kent looking for agates and throwing rocks for Bart. Bart found a rock he liked and Kent kept chucking it for him. When they got back to the truck, Kent threw the rock away. Bart went and got it. Kent threw it again. Bart got it again. This went on for a while and the dog refused to get in the truck. Finally, Kent gave up and put the rock in a bucket in the bed of his truck. Satisfied, Bart hopped in the truck. When they got home, Kent took a closer look at the rock and realized that it was a fossil bone of some kind. Now he was hooked. His interest shifted from agates to fossils, and he began to be sucked into the Emlong vortex.

Kent and Lucy Gibson proudly pose with Kent’s marlin skull and Ray’s chalk drawing.

This was all too familiar to Lucy, whose laundry room had been invaded by concretions and fossils of all sizes and shapes. Kent is obsessed and relentless. He hits the beach first thing, every day. His proximity to the beach gives him a killer advantage over all other fossil finders. I have noticed this phenomenon in other coastal fossil sites, like the famous sea cliffs along England’s Jurassic Coast. Coastal paleontology is a competitive sport.

We pored over his finds and saw a really good cross section of the types of fossils that come from Moolack Beach. There were clams, scallops, snails, and slipper shells, and the bones of fish, whales, dolphins, desmostylians, and pinnipeds. We took the big marlin skull out to the concrete patio, and Ray used colored chalk to flesh out the size of the whole fish. It would have been a whopper, probably in the 200- to 300-pound range. I had never seen anything like this, and I hoped that Kent would consider donating it to the Smithsonian, where it would become a scientific resource.

Kirk and Nick Pyenson with two fossil marlin skulls from the same beach.

A few weeks later when I was back in Washington, D.C., I wandered down to the first floor of the Smithsonian’s East Wing, the floor where we store many of the fossils that Clayton Ray acquired from Doug Emlong. I was looking for the Behemotops jaw that Doug had found at Otter Rock. As I wandered down the hall, my eye caught a familiar shape on the top shelf. I couldn’t quite believe what I saw. It was a marlin skull, slightly smaller but almost identical to the one that Kent had found. I got a ladder and pulled it down. A collector named Melvin Baldwin had discovered the skull on Moolack Beach in 1964 and had given it to Doug who had given it to the Smithsonian. Two guys, two marlin skulls, and the same spot, fifty years later. I photographed Smithsonian fossil marine mammal curator Nick Pyenson holding a picture of Kent’s marlin next to Doug’s marlin and sent it on to Kent. This coincidence shows the importance of museums. Extremely rare finds, even ones that happen only once every fifty years, can be preserved and shared for the future. I invited Kent to come to Washington, D.C., to inspect the Emlong collection and to begin to understand how his hobby might play a larger role in the scientific understanding of the evolution of marine mammals and the history of the West Coast. Eventually, he did donate the marlin skull and the other skulls he had showed us at the Surftides.

Emlong had visited Clayton Ray in Washington, D.C., only once. He had come to see the collections and to understand what it meant that his fossils would forever be part of the National Collection. While he was there, he slipped away one day and went fossil hunting on one of the inlets of Chesapeake Bay. Being Doug Emlong, he found a fossil whale that day.

I wanted Kent to see the famous fossil site known as Calvert Cliffs located on the Chesapeake near Solomon’s Island about 50 miles from D.C., so I arranged for a friend to take him there while I was in a day of meetings. That night, Kent returned to town, and I asked him if he had found a fossil whale. He just smiled and pulled out a big perfect Carcharocles megalodon shark tooth out of his pocket. I can’t say that I wasn’t jealous.

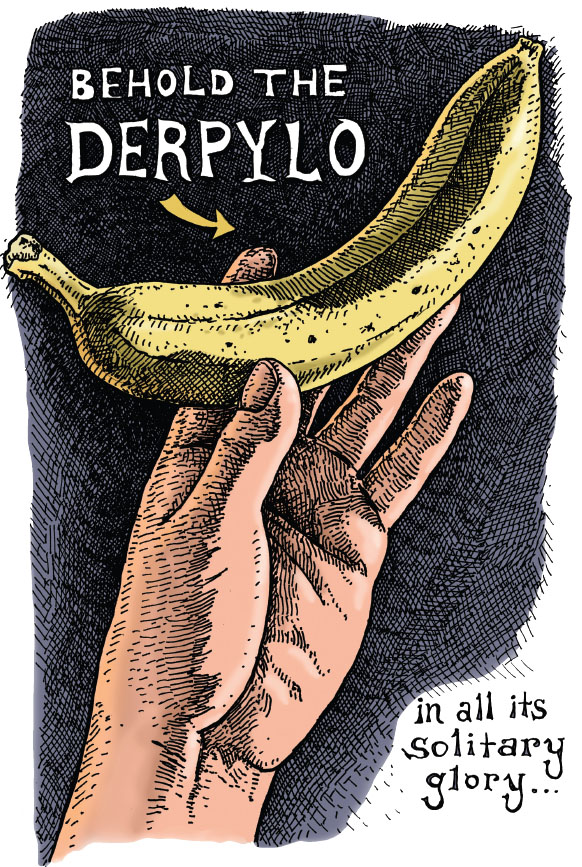

Back with the Gibsons, Kent’s daughter, McKenzie, told us during dinner that she had invented a word. Ray asked if this was something that she did often, and I asked what word she had invented. She answered, “Derpylo.” We demanded to know the definition, and she told us that a derpylo is the lone banana in the grocery store. It is the one that is not part of the bunch. It’s the one that is out there on its own.

Doug Emlong was a derpylo. It turns out that the sea lion Emlong displayed in the 1961 National Geographic wasn’t a sea lion after all. When it was finally removed from its concretion, studied, and analyzed in 1995, it was given the name of Proneotherium repenningi (another fossil named for Chuck Repenning) and was recognized as one of the earliest members of the walrus family tree. The story of the West Coast can only be told because of all the lone derpylos who have devoted their lives to their own obsessions.

A few days later, Ray and I took a break from fossiling to go steelheading. The coastal rivers of Oregon are known for more than their fossils. Frank Boyden had become friends with a tough young fishing guide named Silas Stardance. The child of hippies, Silas was finding his way through fish. We took his drift boat up the Siletz River to a spot where it was only 40 feet wide and launched into the swiftly moving green water. Being February, it was cold and damp. In a boat with two artists, one paleontologist, and a guide, we found ourselves watching the banks as much as the pools and riffles. A few times we stopped to inspect outcrops or fallen blocks of rock. We had Emlong on our mind.

The Siletz was the river that Ken Kesey wrote about in his novel Sometimes a Great Notion. When I first read that book as a teenager, I was struck by the harsh realities of being a logger in a coastal rain forest. If you’ve read the book, you’ll recall that it doesn’t end well, either for the forests or for the loggers. Frank remembered when Paul Newman came to the Siletz to make the 1970 film and how the town of Lincoln City was starstruck.

Just before noon, I hooked into a sea-bright steelhead and eventually fought it into the boat. There is no fish more beautiful than the steelhead trout. Like their salmon cousins, the steelhead spend their adult lives in the Pacific Ocean as full players of the open ocean ecosystem. When the time comes for them to reproduce, they swim from the ocean into coastal rivers, switching from saltwater to fresh water to spawn. The evolution of steelhead and salmon was one of Ray’s many obsessions, and we were happy to be on a river in steelhead country.

That fish turned out to be a derpylo. After six hours of drifting, we were all getting cold and tired. Silas rowed the boat to shore so Frank could relieve himself. I sat in the boat, scanning the cliff banks for signs of fossils. You can’t find them if you don’t look for them, and the funny thing about looking for them is that you often forget that you are looking, and you are surprised when you make a find. My lazy scan caught a glimpse of white. I paused and then recognized an unmistakable pattern of an occipital condyle, the base of a skull sticking out of the rock of the riverbank. I couldn’t believe it. Here we were, floating down Paul Newman’s river with a steel-head in the boat and there was a fossil skull.

I yelled and jumped out of the boat and ran to the bank surging with anticipation. Just before I got to the fossil, I froze and turned back toward Frank. His huge eyebrows could not conceal his twinkle, and I realized that I had been had. I bent down and pulled the skull out of the bank. It was a beautiful complete skull. But it was made of porcelain and engraved with the telltale marks of a certain coastal ceramicist named Frank Boyden.

Frank Boyden’s porcelain prank.