In 2009, the Burke Museum in Seattle decided it would do an exhibit based on our Cruisin’ the Fossil Freeway book. That brought both Ray and me to Seattle several times to meet with the museum staff who were planning the exhibit. At the time, my dad still lived in my childhood home in Beaux Arts Village on the shores of Lake Washington, and using the home as our base, we were in a perfect spot to launch a series of short trips to explore the fossils and rocks of my home state and to revisit some of my favorite spots.

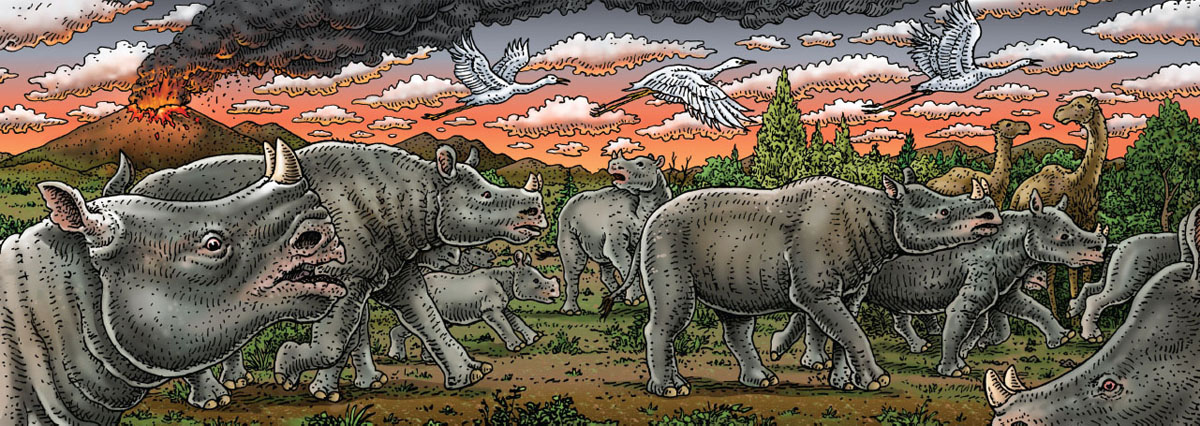

Fifteen million years ago things went from bad to worse for one particular rhinoceros.

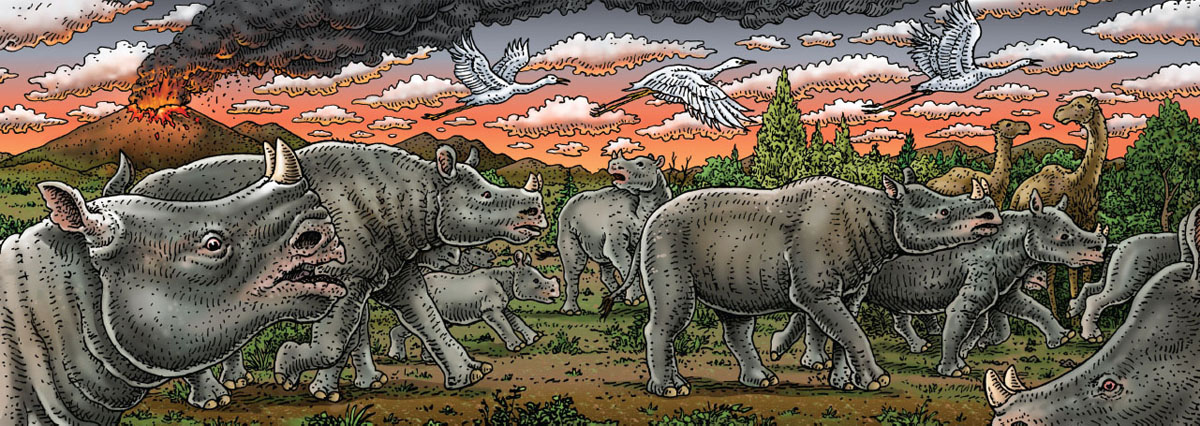

Thirty-two years earlier, I had been a high school junior with a freshly printed driver’s license and access to my mom’s bright orange Audi. That car allowed my artist friend and mentor, Wes Wehr, and me to move freely about the state in search of fossils and adventures. Wes and I met on June 12, 1974. I was thirteen and he was forty-five. I know the exact date because I recently found a note that my mother had written about the visit. I was a fossil-obsessed teenager, and my mom had heard about an artist who liked fossils and who was working at the Burke Museum at the University of Washington. At her urging, I called him, and at his invitation, mom and I visited him. Mom’s note read, “Interesting day for Kirk. He and I visited an artist (but more importantly for Kirk) paleobiologist Wesley Wehr.” The meeting went well. In an odd coincidence, my mom and Wes had been born on the same day in the same year. Both were artists. One had a fossil-obsessed son and one was a fossil-obsessed artist. It was the beginning of a very long friendship.

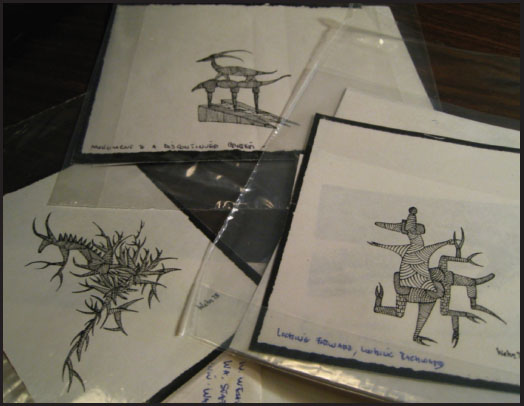

Wes did not do what most people did. He did not have a job, he was not married, he did not have a driver’s license, he had never driven anything, he did not have a house, and he did not have any visible means of support. What he did have was a persistent curiosity about art, fossils, and interesting people. He was a relentless correspondent who spent hours of each day drinking coffee, smoking cigarettes, and writing letters. His many friends included artists, musicians, poets, actors, writers, philosophers, and scientists. Somehow he had convinced the Burke Museum to take him on as the unpaid curator of paleobotany, an assignment that arose from his love for the beauty of the fossil wood of eastern Washington. His own art was remarkably precise and markedly finite. He used to tell me that he could carry an entire show in his leather satchel. His paintings were tiny austere landscapes, rarely larger than a 3-by-5-inch index card. His drawings, done in India ink with a Montblanc pen, depicted tiny beings that were part kachina and part entomology. We became close friends, and I added correspondence and drawing to my tool kit.

Artist, paleobotanist, and mentor Wesley Wehr.

“Monster drawings” by Wesley Wehr.

Wes introduced me to the magical world of scientific literature. For the last 300 years, science has moved forward and aggregated knowledge through the published papers of scholars. Up until I met Wes, I had been trapped in the popular literature of guidebooks and rock-hounding magazines. He turned me on to the Journal of Paleontology and the various publications of the US Geological Survey. With scientific literature in my reach, I was now armed and dangerous. I could learn what the experts knew. Between 1977 and 1989, Wes and I explored Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, visiting old fossil sites and discovering new ones. We met other fossil enthusiasts, and our finds ended up in the Burke Museum collections. Wes played a huge role in my life, launching both may career in paleontology and my impulse to collaborate with artists.

Wes died in 2004, but his memory is strong. He had instilled a lifelong love of art, science, and road trips in me so it was fitting that, five years after his death, Ray and I were back in Washington State and looking at it with fresh eyes.

We grabbed Burke Museum exhibit designer Andrew Whiteman and set off to inspect eastern Washington in order to gather video footage to support the Burke show and to make the exhibit more about Washington State. It was a glorious sunny June day as we drove east out of Bellevue toward the Cascades on I-90. Just a few miles into the trip we drove along the southern shore of Lake Sammamish, and just before entering Issaquah we drove past the remains of a roadcut full of childhood memories.

When I was twelve and had learned how to use a library, I began to research fossil sites that were close enough to my home that I could get there and back in less than two hours. That mattered because I could convince my mom to drive me places if it didn’t destroy her whole day. Sadly, the guidebooks were pretty blank when it came to local sites, so it came down to trial and error. Then one day, Mom and I stopped at a roadcut on a frontage road above I-90 that was only fifteen minutes from our house. She gave me thirty minutes to check it out.

Most of my previous efforts had come up dry, but much to my amazement and joy, the crumbly cliff was full of fossil clamshells. The rock was soft and wet, and it was easy to pull apart with my bare hands. The clams themselves were so delicate that when I pried them loose, the shells would crumble into fragments, leaving a mud cast of their interiors. The thirty minutes passed in a flash, and pretty soon Mom was honking the horn to let me know that she was done and so was I. We headed home, but I was elated because I now had a fossil place that I could easily access. Mom never minded giving me an hour here and there, and thus was born the one-hour fossil trip. Over the next few years, we went there with some regularity, and each time I learned a little more about the cliff.

I found that if I was very careful, I could get the fossils home unbroken, and, when they dried, they hardened up a bit and became more stable. I discovered that although there were mainly clams, I could find other things if I was persistent. And I was persistent.

One day, I discovered a 2-inch-long shell that looked like a miniature hollow elephant tusk. That night at home when I consulted my books, I was able to identify my first Dentalium and learn that is was the shell of a marine animal known as a scaphopod. Not surprisingly, its common name is “tusk shell.” This was a curious thing to me because I had never seen one of these shells while beachcombing or in an aquarium. Here was a creature that first presented itself to me as a fossil. This was to become a pattern.

A six-year-old Kirk shares his wagonload of rocks with a friend.

After I had met Wes, I would visit him at the museum where he told me about paleontologists and how they specialized in very particular things. There were people who worked only on fossil wood, or only on fossil leaves. There were even a couple of people who worked only on fossil nuts and seeds. He had figured out who some of these scientists were and had learned that they were happy to receive letters from people who found examples of what they studied.

Mom kept driving me to the roadcut, and my persistence continued to pay off. One day I found a fossil pinecone. Another time I found a fossil nut. This time, Wes and I packaged up the nut and shipped it off to Steve Manchester, the Camp Hancock alum who specialized in fossil nuts. He wrote back and said that it was an extinct relative of the walnut and that he would like to describe it in an upcoming publication on the evolution of the walnut family. I was starting to get the hang of this paleontology thing.

Then one day, I found a bone. I wondered what kind of outcrop would produce clams, nuts, and bones. I gingerly collected the 5-inch fossil and took it home, where I scraped away the soft matrix to expose a bone that looked quite distinctive. I had no idea what it was so I took it to the Burke where Wes introduced me to Bev Witte, a small stooped lady who worked as the museum’s preparator. Bev was wonderfully welcoming and immediately identified my bone as one half of a dolphin vertebra. That completely surprised me, and then she asked if I would donate the fossil to the museum because no one had ever found a dolphin bone in that place before. She made the point that my find would be of more use to science if it was in a museum than if it remained in my bedroom. It was my first find of any significance and the start of my life of collecting for museums.

As Ray, Andrew, and I drove past the outcrop, I pointed it out and told the story of the tusk shell, the dolphin, and the walnut. It was amazing to think that thirty-five years had elapsed since I had made those finds. Now I was a geologist and I knew a lot more about the outcrop. I knew that it was the Blakely Formation, a marine unit of Oligocene age, and that my fossils were about 30 million years old. The other thing I knew was that the outcrop lay just to the south of an east–west feature known as the Seattle Fault.

Seattle has earthquakes, and I can even remember feeling one in 1965 when I was a kid. But the size and danger of Seattle’s earthquakes has only come to be known in the last thirty years. It turns out that Seattle has a variety of different kinds of earthquakes, and some of them are pretty significant. The Seattle Fault was first recognized as a potential problem in 1992 when scientists literally connected the dots and showed that the Seattle Fault stretches from Bainbridge Island to Alki Point (the spot where Seattle was founded in 1851) to Mercer Island and across Lake Sammamish. The scientists showed that the fault had ruptured 1,100 years ago in a huge earthquake that uplifted several areas, caused tsunamis in Puget Sound, and sent huge patches of forest sliding into Lake Washington (you can still find these submerged standing forests on the bottom of the lake). In the time that elapsed between my childhood fossil forays, the geology of Washington has become impressively dangerous. Actually, the geology hasn’t changed at all. What has changed is how much we know about it.

We continued up into the foothills of the Cascades and finally crested them at Snoqualmie Pass. At a mere 3,015 feet above sea level, this pass is home to Seattle’s most accessible ski area, but its low elevation means that you are often skiing in the rain. It was this fact that cured me of skiing at an early age.

We stopped at a pancake house for breakfast, and because Andrew wanted to make a small film about pancakes. For years, I have searched for good metaphors to describe geology to people who don’t know or care about it. Again and again, I find that food metaphors work the best. Andrew wanted something for the exhibit that would help visitors understand how sediments became rocks, and corpses became fossils. Pancakes make good analogies for geologic formations both because they are flat and have a certain thickness and a certain lateral dimension and because stacks of pancakes make a good analogy for stacked layers of rocks that form the geologic record.

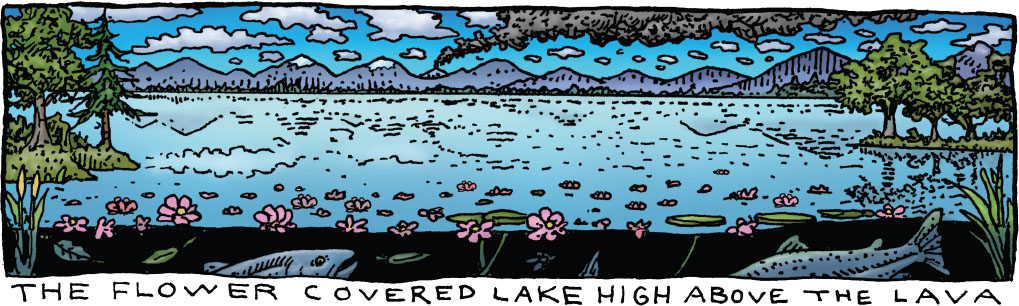

Think for a moment about pouring pancake batter on the flat griddle. As the liquid batter heats and cooks, it stops flowing and solidifies into a pancake. It turns out that eastern Washington is underlain by a whole lot of rock that started its life something like pancake batter. The entire Columbia Plateau of the southern half of eastern Washington is made of stacks of layers of volcanic rock known as basalt that erupted in a series of lava flows between 17 and 14 million years ago. These lava fields extend into eastern Oregon and westernmost Idaho, and in places their total thickness is nearly 6,000 feet. Individual lava layers range in thickness from a few tens of feet to a few hundred feet, and this means that the original lava flows were this depth as they flowed out of cracks and along the surface, sometimes traveling at speeds of up to 20 miles an hour. The temperature of liquid lava is around 1,000°F, which means that huge, incandescent rivers of molten rock were a common and deadly sight in eastern Washington. This could not have been a pleasant thing for the plants and animals that had the bad luck to be in the path of the molten rock rivers.

The view down Interstate 90 of the Columbia River and its canyon cut into Miocene basalt layers.

As we rolled off the eastern slopes of the Cascades, we began to see roadcuts composed of the black volcanic rock known as basalt. This rock often forms distinctive vertical five-sided pillars that look like giant black crystals. The pillars (or columns as they are more commonly called) formed as the liquid lava started to cool. As it cooled, the volume of the lava decreased, creating stress in the hardening rock that resulted in cracks. The intersecting cracks form the pillars.

A few miles past Ellensburg, we started the long, gentle decline down to the Columbia River. The mighty Columbia is the largest and longest river that flows into the Pacific Ocean from North America. Its headwaters are in British Columbia more than 1,200 miles from the ocean, and it winds a very long path before entering the northeastern corner of Washington and flowing across the state, then along the Washington–Oregon border, and finally out to the Pacific at Astoria.

The Columbia was once home to the largest salmon run in the world, but that ended with the exploitation of the river for hydroelectric power that began in the 1930s. I can still remember my first grade teacher regaling us with tales of how he worked on the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam. Now, fourteen different dams block the river, creating a series of long, flat lakes instead of a rushing wild waterway. The dams generate incredible amounts of electricity, but they block the salmon from spawning in the upper thousand miles of the river.

A petrified log entombed in basalt was once a log buried in molten lava.

By the 1940s, the banks of the Columbia near Hanford became the site of a secret nuclear facility that eventually produced the plutonium used in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When I was sixteen, I was selected as part of a group of high school students to tour the Hanford site and learn about the future safe uses of nuclear power. I remember that they gave me a marble that had been radiated as evidence that nuclear power was okay and that we would soon be seeing more nuclear power plants than hydroelectric dams in Washington. A few years later, that idea went away in a spectacular bankruptcy, and we were back to hydroelectricity.

But it wasn’t salmon, dams, electricity, or atomic bombs that drew Ray, Andrew, and me to the valley of the Columbia. As we drove the last few miles down the long hill toward the river, I pointed out tubular holes in the basalt outcrops as we whizzed past. Ray wasn’t really sure what I was pointing at and missed the first few. Finally, I pulled over and stopped next to one of the bluffs. There along the base of the cliff we could clearly see several of the curious tubular tunnels. We got out and walked over to the cliff and peered into one of them. About 3 feet back from the face of the cliff was the clear cross section of a perfectly petrified log. A petrified log in a basalt cliff could mean only one thing: a long time ago, a tree had been entrained in a lava flow.

The fossil logs in the Columbia basalts were first noticed by highway workers in 1927. In 1931, George Beck, a music professor at the Central Washington College of Education, learned about the fossil wood and began to study it. The logs were so well preserved that every detail of the cells were visible, and it was possible to slice thin sections of the logs and identify the type of tree they came from. Beck involved students in the effort, and they began to scour the hills in search of logs weathering out. He was amazed to find that the logs represented many different species of conifers and broadleaf trees, none of which live on the barren slopes today. In 1932, Beck discovered a petrified log that had the distinctive cellular structure of Ginkgo, the maidenhair tree. Ginkgo is a tree that today lives only in China, Japan, and Korea, where it is widely planted near monasteries and temples. Beck realized that the site was significant and approached the state government and petitioned for the site to be protected. In 1935, the Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park was established.

This Washington state park is named after a Miocene fossil tree.

Wes Wehr had started to correspond with Beck in the 1950s and eventually started coming east to search for fossil wood himself. Beck told him stories about the local competition to find petrified logs. The logs were embedded in the basalt, but as the ground weathered, distinctive fossil wood chips at the surface could be an indication of a log in the weathered basalt below. Basalt is a hard rock and digging for logs in the basalt was tremendously tough work.

Beck found himself in competition with a man named Frank Bobo who was in the habit of sprinkling chips of petrified wood in random places in hopes of causing competitors to dig in the wrong places and not rustle his logs. The prize for all this hard work was some of the most beautiful petrified wood in the world. We had entered the weird world of the paleo-lumberjack.

We exited the interstate in the tiny town of Vantage, which is located on the west bank of the Columbia above the Wanapum Dam. What had been a beautiful canyon was now a large lake that had formed in 1959 after the dam was built. The state park is a single building with a few exhibits about the story of the fossil wood and some nearby petroglyphs. Near the entrance to the park there was a big sign for the Ginkgo Gem Shop.

Bill Rose shows off his massive rock saw.

Bill Rose and his wife, Dee, have operated the shop for more than thirty years, and Bill is a man completely focused on petrified wood. I’ve made a point of stopping by his shop for the last three decades, and he hasn’t seemed to age at all. The Ginkgo Gem Shop is a classic example of the western rock shop. Back in the 1960s, just about all western towns had rock shops, but they are now an endangered species. Bill’s joint is unique because of his focus on the local product: Miocene fossil logs. He mines them out of the loose basalt rubble, then slices off round slabs with diamond-bladed rock saws. He then uses finer and finer polishing grits and powders to bring the face of the slab to a high luster. The result is an extraordinary view into the lost forests of the Columbia Plateau.

I had warned Bill that we would be stopping by, and he and his wife and two kids were waiting when we pulled into the lot. Bill had bought out an Arizona rock shop, so the lot was filled with giant concrete dinosaurs and huge red petrified logs from the Triassic rocks on private land near Petrified Forest National Monument by Flagstaff, Arizona. Apparently, Bill was selling so much wood that he needed to start importing it from other states. The Arizona logs were nearly 3 feet in diameter, and Bill had used them as an excuse to buy the biggest rock saw I had ever seen. The circular blade was 6 feet in diameter, and with it, Bill could saw through any petrified log he had.

A petrified log.

Bill Rose with a perfect slab cut from an agatized Miocene log.

He took us into a series of workshops and storerooms, each full of old rock saws and cut slabs of wood. Every space was coated in rock dust; the whole place looked like a volcano had erupted and belched volcanic ash all over his inventory. Time after time, he would wipe away the dust to expose a glassy polished slice of fossil wood. He knew his fossil wood well and announced the species of tree with every slab: honey locust, Douglas fir, oak, maple, hickory, elm, sour gum, sequoia, ash, pine, cherry, apple, sweetgum, and yes, Ginkgo. The forest that had once grown here was a diverse temperate broadleaf forest with a few conifers thrown in for good measure. More than forty species have been found here. Like the forests of eastern Oregon of the same age, this forest was more similar to the deciduous forests of New England and northern China than it was to what grows in Washington today.

While these forests left their logs in the lava, there are sites between the lava layers that also preserve their leaves. One such site at a place called Clarkia in western Idaho exhibits an extraordinary feature. The wet, dense clay at Clarkia has excluded oxygen since the Miocene, and when you split open a block of Clarkia clay, it is actually possible to see a green leaf. Within moments though, the leaf reacts with the modern atmosphere and turns black.

The tree rings are so well preserved that we know how old the trees were when they were buried in lava 15 million years ago.

We bought a few slices of fossil wood and headed across the river. The road climbed steeply out of the canyon and we drove past cliff after cliff of basalt. Ray’s eyes were now trained on the roadside, looking for the round holes that signified fossil logs. He had no luck, and we crested the hill near the town of George and headed north to Ephrata and Soap Lake.

At Soap Lake, we dropped back into a big canyon and headed north toward the Grand Coulee Dam. Unlike the canyon at Vantage that had a huge river in it, the canyon between Soap Lake and Grand Coulee had no river. Instead, the floor of the canyon had a series of small lakes. To a geologist’s eye, a canyon without a river is an odd thing indeed, since it is rivers that make canyons.

Blue Lake.

I was by no means the first geologist to take note of this odd situation. In 1905, a young man named J. Harlen Bretz graduated from college and moved to Seattle to become a biology teacher. The geologic grandeur of the area gripped him, and his interests quickly turned to geology. The concept that the northern half of North America had recently been covered by a 2-mile sheet of ice was an idea that had taken root on the East Coast in the 1870s, and it was pretty clear that Puget Sound had been formed by the southern extension of this massive ice sheet. Bretz decided to go back to school and become a geologist, and he enrolled in the University of Chicago and continued to study Puget Sound. He became a professor at the University of Washington in 1913 and published a detailed report entitled Glaciation of the Puget Sound Region. In it he demonstrated an acute eye for landscape and an intense love of fieldwork. He was a tough critic and bluntly described the work of one of his predecessors as “based on too little fieldwork, and much of it is in error.”

In 1922, Bretz found himself in Soap Lake trying to understand the enigma of the canyon that had no river. North of Soap Lake the canyon broadens, and a huge cliff cuts across the middle of it, creating a feature called the Dry Falls. To the north of that stretches the Grand Coulee, a long canyon that intersected the Columbia River near the site of the Grand Coulee Dam. Elsewhere to the east, the surface of the lava flows are disrupted by huge, erosive divots. Initially, it seemed like the Grand Coulee might just have been an abandoned canyon of the Columbia, and the Dry Falls once Washington State’s version of Niagara. But Bretz looked past the obvious and saw the extraordinary. Armed with his understanding of glacial geology and his willingness to undertake extensive fieldwork, he came to the conclusion that eastern Washington had been inundated by huge floods of glacial meltwater that had eroded the landscape with unprecedented fury. He published his idea of the “Spokane Floods” in 1925 and was immediately attacked by colleagues who would not see what Bretz had seen. It took him forty years to win his argument, but win it he did.

Ray rows across Blue Lake.

The event that triggered the floods was the advance of a lobe of ice from Canada down to what is now Lake Pend Oreille in northern Idaho. The lake bed itself and the surrounding cliffs were gouged out by earlier glaciers. As the south-flowing glacier filled the lake, it blocked a west-flowing river (now known as the Clarks Fork) and created a lake that backed up more than 100 miles and all the way to the present site of Missoula, Montana. Eventually, the lake grew to be more than 2,000 feet deep and contained more than 600 cubic miles of water. The depth and pressure of the water eventually floated, and then shattered, the ice dam, releasing a wall of water that was nearly one-half mile high.

This massive flood roared across eastern Washington at speeds of up to 45 miles an hour and literally resurfaced the state as it went. Eventually, the flood washed into the valley of the Columbia and roared out to Astoria before carving a now submerged canyon at the edge of the continental shelf and spending itself in the Pacific Ocean.

With the pressure released, the glacier pushed back into the lake and created a new dam. The river built up behind the new dam, and after about fifty years, another massive dam rupture created yet another massive flood and started the process all over again. It is now widely accepted that this extraordinary event happened at least forty times between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago.

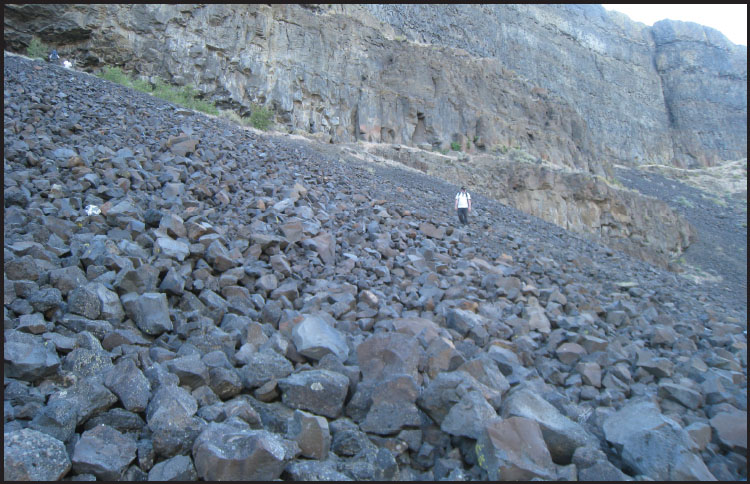

Ray ascends the talus slope.

Most people don’t think of vast flows of molten lava, dense temperate forests, or gargantuan floods as they drive across the broad barren expanses of eastern Washington, but that is this place’s reality.

I had one more trick up my sleeve as we drove north from Soap Lake. I had recently gotten a tip about how to find one of the oddest fossils in North America. We drove past Soap Lake, Little Soap Lake, Lenore Lake, and Alkali Lake and finally pulled over at the north end of Blue Lake and followed the signs into Laurent’s Sun Village Resort where Ray and I plunked down $9 to rent a rowboat. Andrew had his own kayak, and my friend Cathy Lou Brown had driven down to meet us. It was a hot afternoon and the lake looked more green than blue as we set out in our two boats to cross it. We were going to make a serious effort to find the legendary Blue Lake Rhino.

This story started in 1935 when two couples, the Frieles and the Peabodys, from Seattle were poking around the lava cliffs above Blue Lake in search of petrified wood. They were likely using the same search image that had worked for us in roadcuts: look for round holes in the cliffs. On this particular day, they found a particularly large hole. Mr. Friele crawled into the hole, expecting to find fossil wood. Instead, he found several fragments of fossil bone and part of a fossil jaw with parts of six teeth. Mrs. Peabody took these bones to the University of Washington, who sent them to George Beck, who visited the site later that year. Beck found some more bones and shipped them to Chester Stock at Cal Tech, who identified the jaw as belonging to a Miocene rhinoceros called Diceratherium. In 1948, a crew from the University of California–Berkeley Department of Paleontology visited the site and made a plaster mold of the inside of the cavity. When assembled, the mold had the very distinctive shape of a large and somewhat bloated four-legged rhinoceros lying on its back. The rock that formed the walls of the cavity is known as pillow basalt, a type of rock that forms when lava erupts or flows into water. The obvious conclusion was that a rhino (and we’ll never know if it was alive or dead at the critical moment) was in a shallow pool or stream when it was overrun, entombed, and no doubt baked in flowing lava.

Eventually, the lava cooled to stone and was buried by many other similar layers. Then 15 million years passed, and the Spokane Floods eroded canyons and gullies and miraculously eroded open a hole at the tail end of the beast. Then 13,000 years elapsed and the Frieles and the Peabodys arrived at the cliff and found the hole. Now seventy-four years later, we had arrived at the base of the cliff and were surveying it in an attempt to find a hole on the cliff face. No such hole was apparent, but we could see an inviting ledge about 200 feet up the cliff. Someone had painted a white letter “R” just above the ledge, and we took this as a very good sign that we were on the right track. We began to scramble up the steep talus slope composed of jagged basalt boulders. It was hot, but we were in the shade and the day was calm. I was really excited.

At the top of the talus slope we encountered the base of the cliff and were confronted with a little zone of treacherous verticality. Andrew and Cathy worked their way up the cliff and disappeared above us. I followed and was making my way up when I heard the smallest of whimpers. I glanced below me to see Ray completely prostrate on the cliff and utterly unable to move. The Troll had frozen.

I worked my way back down to where he was to assess the situation. It was not good. Ray was unable to go up or to go down. This presented a problem for our little expedition. I had not been aware that Ray had a fear of heights and neither, apparently, had he until it struck him. I maneuvered myself into a position immediately below him and used my rock hammer to dig a flat bench where he could find a stable footing. Now that I had stabilized the Troll, I began to soothe him with the thought of the discovery that awaited us above. After fifteen minutes, his equilibrium returned and we gingerly made our way up to a ledge that was the width of a narrow sidewalk and ran for about a hundred yards along the cliff face. The drop-off below the ledge was not insignificant, and we all walked cautiously as we searched for the legendary hole.

We found several small holes that must have once contained petrified logs, but the large rhino hole was nowhere to be found. Then we found the letter “R,” but there were no holes near it. We had come so far and we were so close, but we were truly stumped. After about fifteen minutes of searching we were about to give up, when Cathy noticed a plastic ammo box crammed in a small cavity at the base of the back wall of the ledge. She pulled it out and opened it up. It was a geocache with a series of notes. Several notes celebrated the success of their authors in finding the rhino. Several others expressed exasperation and frustration at having come so far and having not found the rhino. Then we found a note that said:

COOL TREASURE BUT CAN’T FIND THE RHINO … KNOW IT’S CLOSE BUT. RICK VOGEL BELLINGHAM WA NOW IN GREENVILLE SC. P.S. WOULD BE NICE IF SOMEONE WOULD DRAW MAP TO THE RHINO’S LOCATION. FOUND IT! STRAIGHT ABOVE THIS CACHE. COOL.

Cathy Lou Brown peers out through an opening that was once the back end of a rhinoceros.

We looked straight up about 9 feet above our heads and there was the hole. We were elated, and I was just a bit terrified. As much as I wanted to crawl into the rhino, a 9-foot climb above a narrow ledge above a very long drop did not appeal to me. This was not even an option for Ray. I paused, and in that moment Cathy scrambled up the cliff and disappeared into the hole. A moment later, she reappeared, her impish face grinning from the rhino’s butt.

Cathy luxuriated in the rhino for about fifteen minutes, allowing me time to screw on my courage. I had not come this far not to crawl into the rhino’s rump. So up I went and in I went. Mission accomplished. For a man who loves fossils like a kid, this was a real moment for me. Ray chose not to test his vertigo, instead staying on the ledge below and beginning to compose a song about the sad fate of the baked rhino. With our mission accomplished, we worked our way down the cliff and rowed back across the lake. Nine dollars well spent.

The next day we crossed the Columbia at the Grand Coulee Dam and entered the remote part of Washington known as the Okanogan. We entered the Colville Indian Reservation and drove north along the forested floor of the deep and exquisite San Poil River canyon. We drove north for an hour and entered the little gold-mining town of Republic. It was in this town in the summer of 1977 that I kicked a rock that changed my life.

I got my driver’s license in the fall of 1976, and my friend Wes and I immediately began planning a road trip for the following summer. My mom was delighted to be relieved of the task of driving us and happily gave me the keys to her car. The idea was a big clockwise loop that would take us north from Seattle to the Skagit Valley, east to the Okanogan highlands, and south to the John Day Country of eastern Oregon before stopping in Portland on the way back to Seattle. Wes had been reading the research papers of a USGS paleobotanist by the name of Roland Brown who had passed through eastern Washington in the 1920s. Our goal was to visit some of his fossil sites and see if we could find new ones. It was my first time as the responsible party on a long road trip.

I drove and Wes smoked. He was a slight and very quiet man. He spoke a lot, but he spoke in a whisper. To hear him I had to lean across the stick shift. We departed Seattle and crossed the North Cascades Highway, an amazing mountain road that had only been completed five years earlier. In the town of Winthrop, we found a roadcut that had 120-million-year-old Cretaceous fossil ferns, conifers, and broadleaves. Twenty years later, Ian Miller, a Winthrop kid, would complete a PhD at Yale University and demonstrate that these fossils from the Winthrop Sandstone had grown at the latitude of Mexico, and their fossils had been shifted north on a block of exotic terrane only to be emplaced in northern Washington as stunning evidence for what has come to be known as the Baja–BC hypothesis.

Wes and I continued east through Twisp and Omak and into the Okanogan, arriving in Republic just after noon. Republic was a quiet town located a few miles south of an operating underground gold mine. There was an obvious roadcut at the south end of town, and we spent a few hours turning over rocks and finding nothing. We stopped at the library and asked if anyone knew about fossils. No one did. Wes had received a letter from a Republic woman saying that she had found a perfect fossil flower, but that seemed preposterous, and, in any case, we could not find her.

We stopped at the café and ordered milkshakes and pondered our next move. Since Republic seemed like a bust, we figured that the best bet would be to head straight south into Oregon and see if we could get to the John Day Fossil Beds. My orange Audi was parked on the side of Main Street at the south edge of town. Wes wanted to smoke a final cigarette before we left. I walked around the car to check the tires and noticed that the dirt at the side of the road had pieces of very fine-grained tan shale. I kicked one. It was about 2 inches by 2 inches and it popped open like a little book. And there on both facing surfaces was the most exquisite fossil conifer sprig. In truth, it looked like one of Wes’s little drawings. It was an amazing fossil and it had been lying in the dirt 6 inches from the asphalt of the road.

A view of the town of Republic from the Boot Hill fossil site.

I looked at Wes, he looked at me, and we wordlessly began to unpack our tools. Within minutes, it was quite clear that the drainage ditch was full of treasures. The small flat pieces of shale were sturdy, but they split easily and they were full of gorgeous fossils. This kind of rock is called paper shale, and opening the slabs was like turning the pages of a book. We quickly began to accumulate conifer shoots, alder cones, pine needles, alder leaves, and insects, and then – a perfect five-parted flower. The woman had been right.

Paper shale.

A perfect fossil of the flower Florissantia quilchenensis.

We dug in the ditch until the sun went down and then camped in the city park. In the morning we were back at it, this time on the other side of the road where some actual bedrock was exposed and we could pull out larger slabs. We could not believe our luck. We had stumbled on an amazing fossil site in the most unlikely of places. We stayed for another day and then headed south to Oregon. The rest of the trip was great, but the discovery at Republic changed the future for me, Wes, and the town.

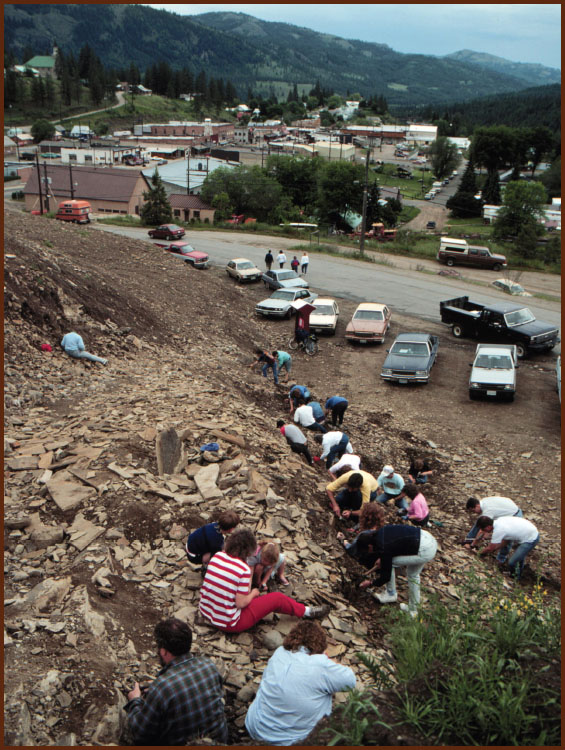

When we got back to Seattle and unpacked our treasures, Wes found that he could easily photocopy them (they were on paper shale after all), and we sent a stack of copies to Jack Wolfe, a paleobotanist (and former Tom Bones protégé) who lived in Menlo Park, California, and was Roland Brown’s successor at the US Geological Survey. Jack wrote back quickly to tell us that our fossils were about 50 million years old and represented the high-elevation vegetation of the Eocene epoch. They were rare, important, and of extremely high quality. Over the next several years, Wes and I returned to Republic many times and mined the corner lot, filling cabinets at the Burke Museum and shipping boxes of fossils to Menlo Park. As the Republic collection grew, so did the diversity of its fossil flora. In 1987, Jack Wolfe published a USGS Bulletin about the site, naming several new species of fossil plant and establishing the Republic site in the scientific literature. In 1989, the town of Republic opened a small museum named the Stonerose Interpretive Center and began offering people the opportunity to dig fossils with the stipulation that any of significance would be retained by the museum for scientific study. Tourists began to visit Republic to see its fossils, and by the mid-1990s, the little museum was seeing more than 10,000 visitors a year. Wes became the resident expert and liaison between the town of Republic and the Burke Museum. Other scientists heard about the site and came to see its gorgeous fossils.

As Ray, Andrew, and I drove into town, the Stonerose Interpretive Center was getting ready to celebrate its twentieth anniversary. Cathy Brown, who had joined us at the Blue Lake Rhino, was the manager of the Stonerose Center, and she had organized a barbecue for our arrival. Stonerose had discovered a second and larger fossil deposit just on the north side of town, and dozens of kids were swarming the slope with screwdrivers, hammers, and juice boxes. There were whoops of joy as real kids found real fossils in a real town. It felt really good to be home.

The dawn redwood, Metasequoia occidentalis.

Fossil leaves of elm (Ulmus) and the Japanese scholar tree (Cercidiphyllum).

A fossil pinecone (Pinus).

That night Ray and I inspected the collections of fossils that the museum had high-graded from the kids. Here was a world-class collection of 50-million-year-old fossil plants, insects, and fish that represented an ancient high-elevation world. One of the fish from this site is Eosalmo driftwoodensis, the earliest known member of the salmon family. Republic is only 40 miles west of Kettle Falls, a spot along the Columbia River where Native Americans used to net Chinook salmon that were headed north into British Columbia to spawn. Those falls are now submerged under the lake formed by the Grand Coulee Dam, but both Republic and Kettle Falls are places that demonstrate the long history of salmon in the Pacific Northwest.

The full suite of plant species from Republic now numbers well over 200, making it one of the most diverse fossil floras known in the world. There were incredibly beautiful fossils and even some slabs with as many as eight fossil flowers – a literal fossil bouquet. The site contains the remains of a number of plants that still live in the northwest like alder, fir, cedar, birch, and pine. It also includes fossils of the rose family, which includes cherry and apple trees as well as blackberries and currants. Today, Washington State produces nearly half of the world’s apple crop and more than half of its cherries. It did not take Wes long to make the connection between the fruit orchards of eastern Washington and the ancient orchards of Republic.

The fossil plants of Republic also carried a surprising twist. Many of them are extinct in North America but have living relatives in China, Japan, and Korea. These included not only Ginkgo, or the maidenhair tree; but also Cercidiphyllum, the Japanese scholar tree; Koelreuteria, the golden rain tree; Pseudolarix, the golden larch; and many others. The appearance of Asian trees as North American fossils is strong evidence that there used to be a continuous forest from Washington to Alaska and across into Asia. Our trip was carrying us north, and we would see much more evidence for this as we carried on.

The Stonerose fossil site is open for digging, so we checked out hammers, gloves, and work glasses from the museum and joined the horde of happy kids who were banging away on the hillside. Fossils are common enough that no one went away without having had the satisfaction of finding an Eocene treasure, and even Ray and Andrew found fossil flowers.

Our trip to eastern Washington had been brief and we left a lot of fossil sites unvisited, but the western half of the state beckoned, and the next day we headed back to Seattle and Puget Sound.