For most of my life, I have collected and studied fossil leaves. As a result, I pay close attention to leaves and can recognize hundreds of different plant species just by looking at their leaves. Paleobotanists, the scientists who do this sort of thing, will often name new species of fossil plant based on their leaves and will publish journal articles illustrating the leaves. When you find a new fossil site and try to identify what you have found, you end up consulting these articles. This has been going on in earnest for more than a hundred years, and my office is full of books and articles about fossil leaves that date back to the 1880s and before. In 1994, I excavated a very unusual fossil leaf site in the town of Castle Rock, Colorado. The site looked like it was a fossil tropical rain forest, and it had more than 100 different types of leaves, many of which I had never seen before. I dug into the books to see if anyone had ever seen any of them before. After some months of searching, I came across a report written in 1936 by US Geological Survey paleobotanist Arthur Hollick that had several matches. His fossils came from Kupreanof Island in Alaska and were collected in 1907. I thought it would be interesting to return to that spot and see if the site also looked like a tropical rain forest. It didn’t seem too likely since the site was in Alaska, but you never know.

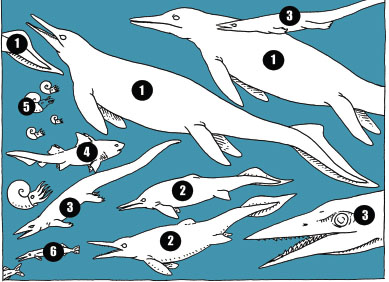

Looking out the window of the Nakwasina dreaming of a Triassic sea full of thalattosaurs, giant ichthyosaurs, and ammonites.

I mentioned this to Ray and asked if he knew anyone who had a boat and would be willing to take us on an Alaskan leaf hunt. A couple of weeks later he called me back and said that he had a friend in Sitka who was always up for an adventure, and that if we helped cover expenses, he would take us where we wanted to go.

Ray and I landed in Sitka on a brisk and beautiful May day and were met at the airport by Barth Hamberg, a fit fifty-year-old landscape architect who designs trails and structures for the Forest Service. His boat was an elegant 37-foot cruiser called the Nakwasina.

Sitka is situated in an amazingly beautiful spot. Located on Baranof Island, it faces out to the open Pacific through an archipelago of small islands and is backed by high peaks to the east. Mount Edgecumbe, a massive snowcapped volcano, sits just 16 miles to the northwest and dominates the scenery. Sitka is the heart of Russian Alaska, and it wears its history proudly. Ray had been working on a painting of the Battle of Sitka and we went to visit the Sitka National Historical Park to look at the site of the 1802 fight between the local Kiks.ádi Tlingit and the Russians. This battle was an incredible example of the clash of cultures that unfolded in Alaska in the nineteenth century. The Russians had moved into Alaska because of the fur trade. When they came to Sitka, they brought Alutiiq hunters who traveled in kayaks called baidarkas. The local Tlingits were initially willing to coexist with the visitors, but eventually hostilities broke out and the Tlingits attacked the Russian fortress in 1802. After initially being repelled, the Russians returned in 1804, with a larger force that included a fleet of more than 400 baidarkas, and they besieged a wooden fort that the Tlingits had constructed. Ray’s painting depicts one of the Tlingit counterattacks where the warriors are wearing wooden armor and helmets that are carved in the shape of sea creatures and scary men. These helmets still exist today in various museums, and Ray’s image captures them in their moment.

Eventually, the besieged Tlingit, realizing they did not have enough ammunition to carry on the fight, slipped away at night and escaped by walking over the mountains to a place called Nakwasina Cove.

But that story is not the reason that Barth’s boat is named Nakwasina. His boat is named after a famous canoe. The story of the Nakwasina canoe was told in the July 1933 issue of National Geographic. For their honeymoon in 1931, Jack Calvin (a friend of Ed Ricketts) and his bride, Sasha Kashevaroff, paddled the Nakwasina from Tacoma, Washington, to Juneau, Alaska, a distance of nearly 1,100 miles. They took their puppy, Kayo, and paddled about 20 miles a day from June 25 to August 16, arriving fifty-three days after they started. Even by today’s extreme sports standards, this was a heroic feat.

The Battle of Old Sitka, 1802.

After their paddle, Jack and Sasha bought a small cruising boat they named the Grampus. In 1932, they met up with Ed Ricketts and Joe Campbell in Tacoma, and together they took the Grampus up to Alaska. This time the Nakwasina was strapped to the roof of the Grampus. Their voyage took them up Puget Sound and through the San Juan Islands, then through the entire inside passage and all the way to Sitka and finally Juneau. As usual, Ricketts collected marine invertebrates, deep conversations abounded, and, by all accounts, the group had a splendid time. Campbell was interested in mythology and religion, and Ricketts was growing more interested in the relationship of science to religion. And they all liked to party. The trip lasted two months, and for Campbell it was “epochal”; for Ricketts, it framed his ambitions to understand the ecology of the entire West Coast.

Ricketts and Jack Calvin published Between Pacific Tides: An Account of the Habits and Habitats of Some Five Hundred of the Common, Conspicuous Seashore Invertebrates of the Pacific Coast Between Sitka, Alaska, and Northern Mexico, which was finally published in 1939. Campbell published The Hero with a Thousand Faces in 1949. In 2015, Sitkans Jan and John Straley and Ed Ricketts’s daughter, Nancy, connected these dots in their book, Ed Ricketts: From Cannery Row to Sitka, Alaska.

Jack and Sasha settled in Sitka in the mid-1930s, and, years later, Barth’s Nakwasina was owned by Jack and Sasha’s daughter, who named it after her parents’ canoe. All of this meant that Ray and I would accidentally be traveling in a boat that was directly connected to Ed Ricketts and seeing the same waters that he saw 80 years later.

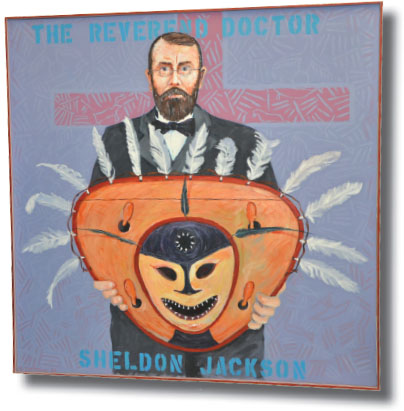

We spent a few days in Sitka, stocking up for our trip and seeing the local sites. I was eager to visit the Sheldon Jackson Museum. Jackson was an aggressively proselytizing Presbyterian minister who arrived in Alaska in 1877 and traveled widely in his search for souls. He founded many churches in remote Native villages and lobbied for the suppression of Native languages in favor of a Bible-inspired English. During his travels, he accumulated a remarkable collection of Native art and utilitarian objects, and, in 1888, he opened his museum in Sitka. The building and the collection are intact today and serve as a time capsule for the Alaska of 130 years ago. We stopped in to see Nadia Jackinsky and Jackie Hamberg, the curators of the collection, and they surprised us with a portrait of the Reverend Jackson that had been painted by Ray’s brother, Tim Troll.

A portrait of the Reverend Sheldon Jackson painted by Ray’s brother Tim.

Tim had served as the city manager for the Yupik village of St. Mary’s in the 1980s and had been very active in connecting local communities with objects made by their relatives and ancestors that are now in museums around the world. He organized the first exhibit of Yupik carved masks in Yupik communities. His portrait of the reverend is interesting because of the tension it expresses between who the reverend was and what he preserved by collecting. This small concrete building in Alaska is a microcosm of the relationship between Native communities and museums worldwide.

The collection itself was one of the best I have ever seen. The diversity of objects made from stone, wood, ivory, shell, skins, intestines, feathers, and metal attested to the human response to life in Alaska. This crossroads between two oceans and two continents has been a hotbed for creativity for literally thousands of years.

We also stopped in at the Sitka Sound Science Center, which houses a small aquarium with a strong research arm and an active program monitoring the humpback whales that migrate into Sitka Sound each year. Out on the sound, marine archaeologists were searching for the remains of Russian ships that had sunk after the battle of Sitka. In town, Tlingit artisans and Norwegian fishermen continue to make this tiny town of 9,000 one of the more interesting places on the West Coast.

The next morning, we packed the Nakwasina, slipped out of the harbor, and headed up Olga Strait along the west coast of Baranof Island. The Nakwasina moved at a stately 6 knots (or about 7 mph), so we were not headed anywhere fast and had time to scan the sea for whales and the shorelines for bears. After a few hours, we entered Peril Strait, a narrow and dangerous passage between Baranof and Chichagof Islands. One particular spot named Sergius Narrows had Barth quite focused. In this little pinch point, the wrong tide could spell a very bad outcome. Barth told us stories of flipped tugboats and crashed rescue helicopters, but he had also calculated our timing so that we were able to pass through at slack water.

At 10 a.m. we passed a channel called Deadman’s Reach and glimpsed a little embayment called Poison Cove. It was at this spot that 150 of Baranof’s Aleuts were hunting for otter when they stopped for a meal of clams or mussels. A red tide had contaminated the shellfish with a poisonous dinoflagellate, and the entire hunting party had died on the spot. Ray knew this story well because he had collaborated with a Ketchikan coffee roaster to make a brand of coffee called Deadman’s Reach (Served in Bed, Raises the Dead).

By the afternoon, we had emerged from Peril Strait into Chatham Strait and could look across the 10-mile-wide channel and see Admiralty Island. We were directly across from the Tlingit village of Angoon, and I knew this name well. Paleobotanist Jack Wolfe had visited the Kootznahoo Inlet just south of Angoon in the 1960s and had found fossil plants that were 20 to 30 million years old. Barth had a different story about Angoon. In 1882, some of the local Tlingit were working for the Northwest Trading Company hunting whales.

Barth Hamberg and his boat the Nakwasina.

An important Tlingit was killed in a whaling accident, and the tribe demanded reparations. The company appealed to the US Navy in Sitka, who responded by shelling one of the Native villages. I had never really thought about the naval engagements of the Indian wars. When I became the director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, I was visited by an amazing group of Tlingit dancers from Angoon who were happy to hear that I had seen their village and were startled to hear about its fossil plants.

If you look at Chatham Strait on a map of Alaska, you will see that it is as straight as a ruler, a sure sign that the strait lies above a geologic fault. It is, in fact, one of the largest faults in Alaska. It trends north from Angoon before arching around to the north side of Mt. Denali and then continuing back to the southwest and out to the Bering Sea. Like the famous San Andreas Fault, the western side is moving north relative to the eastern side. The means that Baranof Island is moving north relative to Admiralty Island in the same way that Los Angeles is moving north relative to San Francisco.

We headed south down the channel and soon began to see humpback whales, Dall’s porpoises, harbor seals, and otters. We spent the next day exploring the east side of Baranof and ended up anchoring late in the evening at the head of Red Bluff Bay. After dinner, Barth and I decided to go take walk and motored the inflatable dingy toward shore. As we approached the beach we spotted a brown bear in the distance. We entered the mouth of a small creek that was emptying into the bay and spotted two more bears. We landed the dinghy and climbed up onto the beach, taking care to keep an eye on the three bears. As we panned the shore with our binoculars, we spotted a mother bear with three cubs. With a total of seven bears in full view, we decided that it might not make sense to take that walk after all.

The next morning, we headed out across Admiralty Sound toward Kupreanof Island. This huge open body of water is famous for its feeding humpback whales who work as a group to trap fish in a net of bubbles. To do this, several whales dive straight down in a corkscrew pattern and exhale as they dive. This creates a rising cylinder of air bubbles that surrounds and traps schools of fish. At the bottom of the dive, the whales turn upward and, as a group, swim up the center of the bubble cylinder with their mouths agape. It is a remarkable thing to see half a dozen 50-foot-long whales erupting from the calm surface of the sea. We were hoping to see this as we crossed the sound, but all we saw was the occasional whale spouting or fluking up before diving.

A precarious rock formation on the shore of Admiralty Sound.

Humpback whales feed by trapping their prey in nets made of bubbles.

Toward afternoon, we approached a small group of islands off the north side of Kuiu Island. We decided to go ashore and check out reports of fossiliferous marine limestone. Barth nosed the Nakwasina into a narrow channel, and we found a safe place to drop the anchor. The tide was low, and about 9 feet of normally submerged shoreline was exposed. We rowed to shore and clambered onto the slippery rocks and starting looking for interesting marine life. The intertidal zone was extraordinarily rich and completely covered by a huge variety of kelp and seaweed. Technically, seaweed is marine algae, and it comes in a multitude of types and colors, including brown, green, and red. The rock walls that were exposed by the falling tides showed a remarkable zoning of different colors. In addition to the red, brown, and green algae, there were black, white, and orange lichens, and the whole shoreline looked like a stack of Neapolitan ice cream. Fortunately, Barth had a copy of Mandy Lindeberg and Sandra Lindstrom’s A Field Guide to the Seaweeds of Alaska on board. We could see what had drawn Ricketts north and wished that he had lived to explore more of Alaska. Under the seaweed we found crabs, worms, snails, chitons, clams, and amphipods, and the place seemed completely untouched by pollution or people.

We hiked into the woods and walked on a forest floor that was like a thick sponge. Lichens, mosses, herbaceous plants, and ferns covered the ground so thickly that it wasn’t possible to see the soil. Barth had taken us to see some really huge trees and eventually we made our way to a grove of immense Sitka spruce. These remarkable trees made me start to wonder about the geologic history of the Tongass Temperate Rainforest. When did it form? How was it affected by the ice ages? The answers to those questions were closer than I imagined.

We emerged out of the woods onto a rocky shoreline and realized that the only surface that was not completely covered with life was a narrow strip just above the high tide line. Here neither the marine nor the terrestrial life-forms flourished and it was actually possible to see the rocks. And the rocks were full of fossils. We crawled around and found crinoid stems and brachiopod shells. These rocks were Paleozoic, at least 300 million years old. Like the rocks at Kasaan and Glacier Bay, these fossils had formed not only a long time ago but also a long ways away. The emerging realization that drifting microcontinents carry with them their own fossil history is one of the many things that makes the interpretation of Alaskan geology so difficult and so exciting.

We reunited with the Nakwasina and motored over to the Tlingit town of Kake to refuel. Kake is home to a 128-foot totem pole, the tallest in all of Alaska. Like Angoon, Kake had been shelled by the US government, but this time it was the army in 1869, the same year that Seward had purchased Alaska from Russia. The Tlingit were not amused by the sale since it was their land to begin with and no one had bothered to ask them. Tensions brewed, fights broke out, people were killed, and cannons were fired.

After fueling up, we motored south along the coast. A few weeks earlier, we had planned a rendezvous with Jim Baichtal, and we radioed him while we were under way. He was camping on a nearby island with a small field crew. We pulled into a small cove and dropped our anchor. A few minutes later, Baichtal and two of his team came roaring into the cove in what can only be described as the perfect maritime fossil-collecting vehicle. It was an aluminum sled boat with a landing craft door for a bow and a deck full of tools. It was like an amphibious pickup truck. Baichtal had wryly named it the USS Suspect Terrane. Barth pulled out filets of white king salmon and began to grill them. Baichtal produced some steaks cut from a musk oxen that he had shot with a flintlock musket and began to regale us with tales of Alaskan geology.

Jim Baichtal’s landing craft, the aptly named USS Suspect Terrane, made for easy access to the beach.

It takes a while to get used to Jim because you initially think he’s telling tall tales. But the longer you listen, the more you realize that his stories check out, and that he is an amazing guy who has direct access to the incredible geology of a large and remote place. It had been Ray’s idea to include Jim on our expedition, and it was a very good idea indeed.

Jim had recently discovered a submerged volcano 10 miles offshore of Cape Addington on Noyes Island, about 100 miles south of where we had anchored. They found and mapped the volcano using sonar but had camera footage from submersibles that showed pahoehoe lava at a depth of 350 feet below the surface of the sea. This kind of lava only flows at the surface, so the volcano must have been at the surface when it was erupting about 15,000 years ago. This sounds crazy, but it makes sense in a world where the sea level was rising and the land was sinking. Jim had used geology to prove that the coastline was much wider when the first humans made their way into North America from Asia. He also showed how rapidly the world can change.

Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia occidentalis) fossils on the shore of Kuiu Island.

It was cloudy when we woke up, and for some reason we had chili for breakfast. Jim and his crew returned from their camp, and we all hopped into Jim’s sled to go off in search of a fossil site that had last been visited in 1907. Both Jim and I had read the original reports, and they were pretty vague as to where we might find the fossil leaves. Even if we found them, there was no guarantee that I would find the ones I was looking for.

The good thing about geology is that there is a certain level of predictability. We had increased our odds by timing our arrival with a very low tide so we could see all of the rocks that the guys back in 1907 had seen. As we motored along the coast, we noticed that the falling tide had exposed a flat terrace of bedrock. That was a good sign, but the other thing we noticed was that there were large wheelbarrow-sized granite boulders lying on the terrace. These were obviously glacial erratics (boulders that were transported into an area by a glacier or ice sheet and were left lying on the landscape after the ice melted), but it meant that boating was going to be quite hazardous unless we moved very slowly.

Jim nosed the boat onto the beach, and we ran off and started cracking rocks to see if there were fossils. The bedrock exposed on the beach was sandstone, shale, and conglomerate, which was a good sign because it meant fossil leaves were possible. A few of us found some carbonized fossil logs, which was even better news since it meant there were plants here. After an hour of not finding any fossil leaves, we got back on the boat and moved down the beach and tried again. By now it was raining, but we were in Alaska so it didn’t matter. We tried another spot with no luck and kept going.

Then Jim spotted a mink on a log up at the top a beach and thought that seemed like a good sign. We pulled ashore again and scattered across the wide beach. Up by where the mink had been, I found some shale that had some poor leaf impressions. A good sign, but not what we were looking for.

Jim and Barth were working down near the water’s edge, and Jim was using a big hammer to move and break a lot of rock. It started raining harder. Then Jim yelled, “Is this what you are looking for?” Music to my ears, and I rushed down to the shore where he had split a flat rock the size of a dinner tray. The exposed surface of the rock was covered in Metasequoia leaves – the very same kind of conifer that I had found in Republic, Washington, in 1977.

Now it was pouring, but I was really excited and we started pulling up slab after slab and the leaves started coming. I split a big slab and there, right in the middle of it, was a 10-inch-long complete leaf of the same species that I had found in the Castle Rock, Colorado, site and that had also appeared in Hollick’s 1936 report. We had found the right spot.

We kept splitting rocks and finding more fossils. I had been hoping to find fossil cycads, and we found them as well. I could not believe my luck. By now, the tide was flooding and time was running out, so we packed up our fossils in milk crates and loaded them onto the USS Suspect Terrane. We departed with me knowing full well that I would return to this place.

We spent the next few days prospecting the areas for new sites. While we found several, none were as nice as the site by the mink on the log. We saw black bears, porcupines, Sitka black-tailed deer, and an incredible number of sea otters. We counted more than 200 rafts of otter before we stopped bothering. Jim called them sea weasels and noted that their arrival in this bay had meant the end of the Dungeness crabs. Otters are a keystone species, and their presence usually has a dramatic positive effect on the ecology of the kelp forests because they eat the sea urchins that eat kelp. But since people like to eat Dungeness crabs, the sudden growth of a local sea otter population is sometimes not welcome.

Landing on Hound Island.

At the end of the second day, we motored over to Hound Island, a small tree-covered island where Jim and his crew had been camping. They were prospecting for Triassic marine fossils in a dark-gray shale that was exposed in the intertidal zone. Ray and Jim had been here before, and Jim had found enough individual bones to lure scientists from Dallas, Seattle, and Fairbanks to this small, remote island. They had recovered parts of a Shonisaurus, a whale-sized marine reptile, and on his last trip, one of his team had found the back end of a small 10-inch-long marine reptile. He sawed out the slab of rock that he hoped would contain the skull and shipped it to Fairbanks. The guys in Fairbanks hired fossil preparator J. P. Cavigelli from Casper, Wyoming, to fly to Alaska to use needles to see if he could find the skull. I looked at the slab in Fairbanks and deemed the task hopeless. But I was wrong. J. P. teased out a perfect skull with a needle-nosed snout. With the complete skeleton exposed, it was clear that the skeleton was a new and unknown species of a group of animals known as thalattosaurs.

After four days of digging in the rain, we headed back toward Sitka and Jim took off to his home in Thorne Bay. Before he left, he gave me the coordinates of a fossil site we could check out on the way back. Barth steered the Nakwasina back out into Frederick Sound and around the north end of Kuiu Island. The sun had finally come out and it was a splendid afternoon. I was feeling really good about finding the fossils near the mink log.

As we cruised slowly along the forested shoreline, I scanned the cliff face for possible fossils. The three of us were up on the top deck enjoying the sun and enjoying life. We could see for miles, and there was not another boat around.

As I glanced at the cliff, I caught a glimpse of something that didn’t look quite right. I trained my binoculars on it and to my amazement, I was looking at a red ochre face. It was a Tlingit pictograph of a face surrounded by jagged rays high on the limestone wall. Neither Ray, Barth, nor I had ever seen anything like it. It did not look too welcoming.

Barth idled the engine, and we sat floating about 40 yards from shore and thinking about our luck. Just then, a humpback whale surfaced between us and the shore. It had come up from behind us and was intent on feeding right up against the cliff. As we watched, it would dive again and again, always surfacing within 20 feet of the rock wall. Barth slipped the engine into gear, and, being mindful to keep our distance, we kept pace with the lazily feeding whale. For the next forty minutes we shared the afternoon with the whale. Finally we pulled away and headed toward the small embayment that Jim had pointed me toward. As we entered the bay, I scanned the shore for the feature Jim had described. Just then, a small black bear sprinted across the beach and up into the woods.

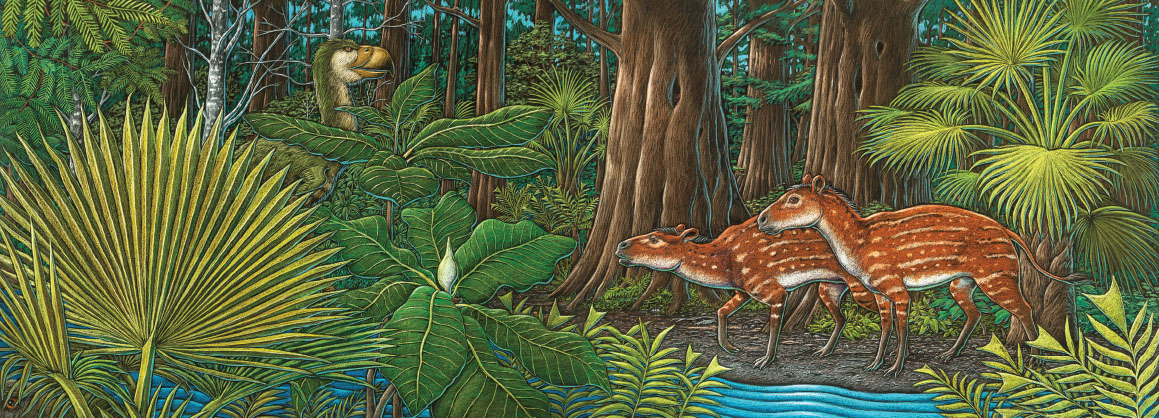

The Tongass palm forest of the Paleocene.

Mississippian-aged fossil coral covered with modern barnacles.

Barth dropped the hook and we rowed ashore. The entire beach was a 350-million-year-old coral reef composed of a variety of corals, including the solitary horn corals and larger masses of colonial coral. We walked around in the lengthening evening light, amazed by this ancient reef and the odd circumstances that had placed it on a modern shoreline where it was encrusted with barnacles, mussels, and seaweed. It seemed so odd that a 350-million-year-old shoreline would once again be a shoreline. That’s when it really hit me about the antiquity of the West Coast, the eternal coastline.

It was a really nice way to end the day and the trip. The next day we motored all the way back to Sitka. At the Sitka airport, everyone carried the classic Alaskan fish boxes full of salmon and halibut. I had fish boxes too, but mine were full of fossil leaves.

Jim Baichtal using a diamond saw to loosen up the bedrock of the beach.

Jim Baichtal, Kirk, and Ray celebrate the discovery of the Kupreanof palm frond.

Twenty months later, Ray, Jim, Barth and I returned to Kupreanof, and this time I brought a film crew from London. We were filming “Making North America,” a three-hour NOVA special that was a biography of the North American continent. The crew and I had just been filming on top of the Juneau Icefield and had flown to Kake. Barth, Ray, and Jim arrived by boat. We came to film fossils in order to make the point that the West Coast of North America was, in part, composed of suspect terranes from elsewhere in the world.

We returned to the mink log site at low tide and started cracking rocks and finding fossils. It was a sunny day, and the film crew was getting decent footage, but the fossil leaves weren’t showing up that well on the camera and the director was getting a bit frustrated. Then I noticed something. It was a little piece of palm leaf about 4 inches long. If there was a little piece of palm, then it was possible we could find a whole palm leaf. Knowing that you can’t find a big leaf on a little rock, I urged the guys to pry up larger slabs. They worked hard and we split a lot of big slabs, but we were coming up with “big nothing.” With the tide coming up, we worked harder. Ray and Jim were prying away at an outcrop that was only a few feet from the advancing tide. I looked at it closely and realized that they had the edge of a palm frond. We all got together and drove chisels into the rock. Finally, we slipped a crowbar into the crack and, on the count of three, we heaved and pried the heavy slab up.

Much to all of our utter amazement, the slab contained the central portion of a huge palm frond. We found it, on camera, and minutes before the tide flooded the outcrop. Again, I could not believe my luck. We quickly carried the slab up the beach and then pulled out two adjacent pieces of equal size. When all was said and done, we had found a palm frond that was 7 feet wide!

Ray and I both thought about the palms of Chuckanut Drive near Bellingham and this palm on Kupreanof Island and started to wonder about the climate implications. I cannot imagine a better way to describe global climate change than by uttering these two words: “Alaskan palm.”

We boated away from the site and headed south toward Prince of Wales Island. Well out into open water between two islands and about 2 miles from shore, we passed a couple of seals. But something about those seals seemed wrong to me. I didn’t recall that seals had big ears. I yelled to Jim to turn the boat around and have another look. When we got close, we realized that they weren’t seals at all, but a pair of swimming wolves. Embarrassed, the wolves rapidly swam to the nearest island and disappeared into the forest.

We continued south so that Jim could show us the karst caves full of bear skeletons, and all I could think about were submerged volcanoes, Alaskan palms, and marine wolves.