Four years later, Ray and I went to Port Townsend to see the Western Flyer, the old sardine fishing boat that Steinbeck and Ricketts had used to travel to the Sea of Cortez in 1940. After a strong literary start, the boat had gone back to the tough life of fishing. It fished ocean perch off of Oregon, then king crab out of Kodiak. It sank in Kodiak and was salvaged and sent to tender salmon in Ketchikan. It sank there and was taken to Anacortes where it sank a third time. The third time was not a charm, and it sank for the fourth time in La Conner. This time, someone who understood its history and meaning bought the boat. John Gregg is a mining technician and designer of remotely operated vehicles used in marine salvage and exploration. He loves fossils and history. He floated the boat and brought it to the shipyard in Port Townsend, where the restoration began. Given its history, the Western Flyer was in pretty good shape, a testimony to its builders and the solid wood they used. Gregg’s plan was to restore the boat and use it to teach science and marine ecology in small towns up and down the West Coast.

We had not met John, but Ray was with me in Washington, D.C., when his brother, Andy, dropped by the Smithsonian. Andy Gregg told us all about John’s plan for the boat and showed us a drawing of the remotely operated vehicle that he had designed to be used on the Western Flyer. To our amazement, the device was shaped like a large pink-striped ammonite. Ray had just finished designing the cover for this book and, as you can see, sitting on the stern of the Nakwasina is a giant pink-striped ammonite.

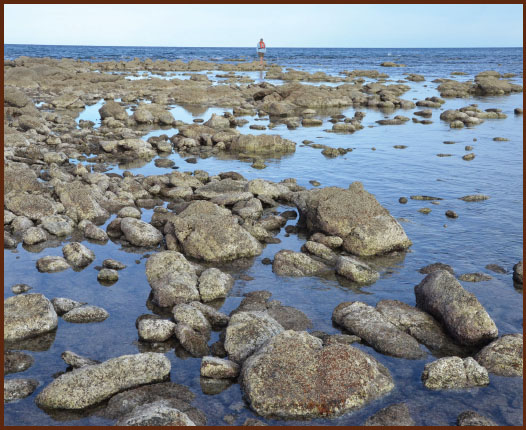

After visiting the Western Flyer, my wife, Chase, and I went on a cruise to the Sea of Cortez with the National Geographic Society’s Committee for Research and Exploration. We were joined on the ship by a variety of scientists. Jorge Velez-Juarbe had just taken over Larry Barnes’s job as the curator of fossil marine mammals at the NHM in Los Angeles, and he was excavating sites on the Baja peninsula that were producing early sea cows and desmostylians. Susan Shillinglaw, the head of the John Steinbeck Center in Salinas came along with her husband, a Ricketts historian and squid biologist, William Gilly. In 2004, Gilly had filled a boat full of scientists and retraced the path of the Western Flyer in the Sea of Cortez, so he knew the spots where Ricketts had made his collections. On the last evening of our cruise, we went to Punta Lobos and wandered around the same tide pools that Ricketts had collected from seventy-five years earlier.

We never do all the things that we want in life, but we try. We are products of where we come from, passions we gathered as children, and the impressive imprints of our mentors and heroes. The world has an amazing story that is emotional at its core. We chose to tell this story as a collaboration of art and science because, for us, the beauty of things is derived from their shape, history, and meaning.

At its heart, the The Log from the Sea of Cortez was a story about an unfinished exploration and an ongoing friendship. So it is with our story. Steinbeck humanized science through Ricketts at a time when science and art were seen as far apart. Our intent is to use art, narrative, humor, fossils, and museums to integrate the deep time history of the West Coast and open its incredible story to people who have previously only known or loved parts of the story.

The Western Flyer up on blocks in Port Townsend.

The tide pools at Punta Lobos on Isla Espíritu Santo in the Sea of Cortez.