PANIC, reprisals, and intense legislative scrutiny of free Negroes followed the discovery of Denmark Vesey’s conspiracy. But as nightmares of slave insurrection faded, South Carolina gradually settled down. Whites found it difficult to sustain eternal vigilance when the specter of Vesey failed to materialize in the daily behavior of free people of color. Rigorous enforcement of the laws regulating the lives of the state’s free Negro population interfered with ordinary, necessary activity. As white anxieties relaxed, the laws lapsed into dormancy. They remained on the books, however, ready to be invoked any time white fears mounted. After 1822, spasmodic enforcement punctuated long stretches of neglect. Even at the height of the fear in 1822, whites did not deny South Carolina’s free Negroes the legal right to property. Had whites formally crushed the economic aspirations of free Afro-Americans, they would have risked driving all free Negroes down Vesey’s path into an alliance with slaves. The possibility of economic progress within existing society gave free Negroes a stake in maintaining the distinction between themselves and slaves, even though for most free people of color the stake was more an opportunity than a reality.

William Ellison made the most of the opportunity. Having earned freedom in 1816, he set out to give it an economic foundation. By 1822, at the age of thirty-two, he had already achieved more than most white Southerners attained in their entire lifetimes. His early success served as a springboard to extraordinary advancement in the next two decades. His gin business flourished; his family matured; his reputation among whites grew; and he became a planter. Between 1822 and the mid-1840s he gradually built a small empire, modest by Stateburg standards, but by most other measures in the antebellum South, magnificent. Ellison was a living refutation of the dominant white assumption that to be free and Negro inevitably meant to live as a useless, poverty-stricken parasite.

Property rights in the Old South included the right to human property, and exercising that right was the surest means of gaining wealth. As Ellison climbed up from slavery, he acquired slaves in increasing numbers. Owning slaves also provided him a kind of insurance. As a master, he effectively demonstrated to skeptical whites that race did not define his loyalties. Whites could never entirely overcome their suspicion that free Negroes were unsound on the issue of slavery. In Denmark Vesey, they had seen racial loyalty outweigh the law, economic self-interest, and the certainty of ruthless punishment. By owning slaves, Ellison broadcast his orthodoxy on fundamental matters and confirmed that he was motivated by safe, mundane, and thoroughly acceptable acquisitive instincts. Whites could see that William Ellison’s primary loyalty was not to the black masses with whom he shared racial ancestry but, like themselves (with whom he also happened to share racial ancestry), to self-advancement within the existing social order.

The magnet of economic self-interest—even of greedy accumulation—probably attracted William Ellison as much as most people. But as a free man of color in a slave society, Ellison had a compelling reason to respond to the attraction. While poverty could snare anyone, white or black, slavery was reserved only for those who were not white. Above all else, Ellison sought to defend his family’s freedom, and the primary means available to him was economic advancement. For Ellison, his wife Matilda, and his daughter Eliza Ann, slavery was no vague abstraction. For them and the other members of their family, freedom had no guarantee. Ellison was aware of just how fragile and vulnerable his family’s freedom was. He attempted to use his wealth to construct a sanctuary that could provide security and safety. Ultimately, no free Negro was immune to white power, but Ellison did all he could—including becoming the master of others—to buttress his family’s position as free people.

Success followed success, but not automatically. Thousands of whites who managed to climb into the master class later fell from it. Perhaps because Ellison was a free man of color and understood that the stakes for him were higher than for most others, his way of approaching business, his way of looking at the world, was profoundly conservative. In any undertaking, he seems to have anticipated all that could go wrong. He moved cautiously, deliberately, measuring each step. Hindsight reveals a pattern in his accumulation, suggesting that from the beginning he adopted a disciplined economic strategy. As an artisan manufacturing the single most important machine in the antebellum South and later as a producer of the South’s most important crop, Ellison worked in the mainstream of the region’s cotton economy. Seeking success within the dominant economy tied him to white standards, values, and institutions. For more than four decades he blazed an uncharted path in a risky world made all the riskier because, to most whites, he was black.

The trajectory of William Ellison’s career inclined upward, not in a series of quick jumps but in a steady, gradual climb. So far as we can tell, his economic ascent was unblemished by even one careless investment or imprudent business decision; few of the wealthy whites he served as ginwright could have claimed as much. Year after year he patiently followed the course he believed offered the most for himself, his children, and their children. On the eve of the Civil War Ellison could stand at his home in the High Hills and look out on a vast panorama of South Carolina geography, and a good fraction of what he could see was his.

“WILLIAM ELLISON, GIN MAKER,” reads more than one document.1 Most white people with whom Ellison did business considered their names sufficient to identify themselves. But Ellison identified himself with his work. It was an accurate label. From his boyhood in William McCreight’s shop through his forty-five years in Stateburg, Ellison made his living building cotton gins. Gin making was the foundation of his economic success and the craft he passed on to his three sons and his first grandson. Linking his name to his craft indicated how he wanted to present himself to white society. He did not want his white neighbors to forget the service he provided the community. Gin making gave him and his family much of the security they enjoyed in the slave society of the High Hills. Even after the gin business no longer generated the major part of his family’s income, Ellison continued to identify himself as a gin maker.

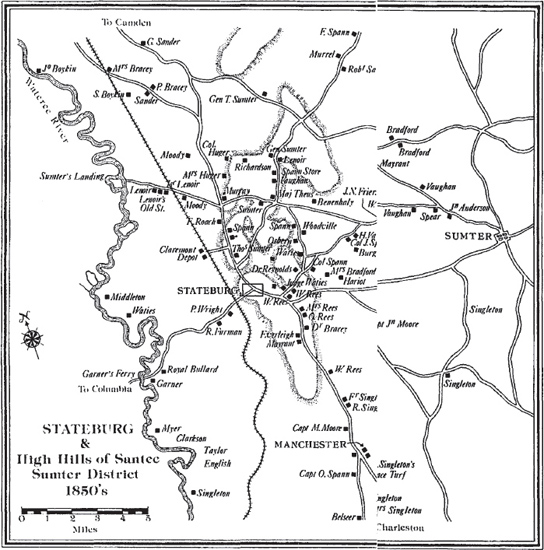

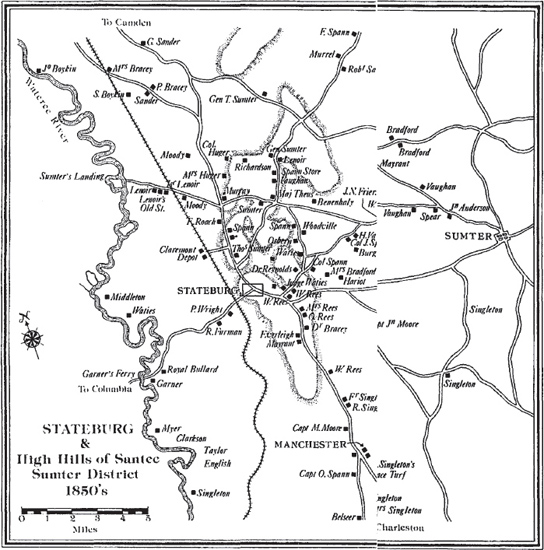

Ellison’s trade tied his economic fate to cotton. In 1816 when he arrived in Stateburg, South Carolina was the leading producer of cotton in the South.2 In less than a decade, however, contemporaries claimed that the state was finished as a major cotton producer. During the 1820s and 1830s the opening of fresh, fertile cotton lands in the west and heedless agricultural practices at home caused the Palmetto State to tumble from its preeminence in cotton production.3 Tens of thousands of South Carolinians joined the “cotton rush” to the west. In December 1835, a newspaper in Camden reported that the “tide of emigration still flows westward. During the week … no less than eight hundred persons passed through this place for the far west[;] of course we include white and colored.”4 One Sumter District resident remembered that the roads were “daily thronged with a continual stream of vehicles of every conceivable class and description, laden with women, children and household stuff, and accompanied by their owners on horseback or foot, with their negroes, dogs, and sometimes cattle, all bound for the new lands in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi.”5

South Carolina stubbornly proved the prophets wrong. Despite the warnings and the emigrants, Ellison had not hitched his wagon to a falling star. The state lost its lead in cotton production and may even have suffered a slight decline in its crop in the 1830s and early 1840s, but cotton continued to dominate the economy. Statewide, production more than tripled, from 50,000,000 pounds in 1821 to 168,000,000 by 1859. The middle districts, the principal market for Ellison’s gins, showed even greater gains in the last two antebellum decades, advancing from 19,000,000 pounds in 1839 to 79,000,000 in 1859, more than a fourfold increase.6 Since slaves supplied most of the labor for these bumper crops, the slave population continued to grow, increasing by 144,000 between 1820 and 1860, pushing the state’s black majority up to 58 percent.7 The west’s staggering crops did succeed in depressing cotton prices, but that concerned white planters more than William Ellison, ginwright. Production—not profitability—determined the number of gins planters needed. Of course had planters been unable to afford his gins, Ellison would have been in deep trouble. But the price of cotton never sunk so low that it was unprofitable to grow in South Carolina, just less profitable than on the more fertile soils in the west.

Skidding cotton prices may have depressed what Ellison charged for his gins. In 1817 his earliest advertisement offered gins at $3 per saw, and that is the price Mrs. Rebecca Singleton paid Ellison in 1825 for a fifty-saw machine.8 As early as 1847 and thereafter until the Civil War, Ellison’s advertised price was only $2 per saw.9 The decline in price may have reflected the slump in cotton prices, as well as lower costs of certain materials, small efficiencies in production, and rising competition. Since his gin shop ledgers have not survived, it is impossible to tell. In any case, Ellison at least occasionally sold his gins for more than his advertised price. In 1836, for example, Ellison built a gin for John Singleton’s Deer Pond plantation and charged $2.75 per saw, but this elevated price may have reflected the gin’s special features, which included “steel saws” and “steel plated ribs.”10 Whether Ellison’s gins sold for $3, $2, or some price in between, they continued to return a generous profit.

Expansion to the west put South Carolina’s planters at a disadvantage in the cotton market, but it gave William Ellison fresh opportunities. Emigrants from the High Hills were not necessarily lost to Ellison. When his former customers reestablished themselves on new plantations in the west, they sometimes remembered the quality of the Ellison gin. “I have engaged W. Ellison to make me a gin to be sent hiar erly in the spring,” Caleb Rembert, a former resident of Sumter District now living in Marengo County, Alabama, wrote to a friend in March 1836. “If you should se him reqest him to hurry with it or our river may becum so low as to prevent the boats from runing, and if that should be the case it will be a disappointment to me as I depend on him intirely.”11 In September, just in time for the ginning season, Rembert announced, “I have got it in my Gin House.”12 For his gin, and crating, hauling, draying, storing it in Charleston, and shipping it by sea, Rembert paid Ellison $184.13.13 In the same year, H. Vaughan, another former resident of Sumter District who had settled in Benton, Mississippi, informed a Sumterville friend that “Ellison promises to send me another gin.” He added proudly, “My crop was 356 bales of about 430 lbs each—220 bales have been sold at an average of about 16½ c.,” an announcement likely to warm Ellison’s heart and bring tears of envy to the eyes of all but the richest Sumter planters.14

How many machines Ellison shipped out of South Carolina is unknown, but only a superior gin could have commanded such loyalty and been worth the extra trouble and expense of shipping and handling. One white resident of Sumter District claimed many years later that Ellison’s was “the best cotton gin” made before the Civil War.15 Another declared that for more than fifty years the Ellisons “manufactured here the standard cotton gin of the south, the Ellison Cotton Gin.”16 Whether or not they were the best, Ellison’s gins were good enough to allow him to retain his local market, which in the long run was growing, and to capture a slice of the new market in the west that expanded at a phenomenal rate. Between 1820 and 1860 the South’s cotton production multiplied by a factor of ten, and Ellison netted his share of the profits from both the Southeast and the Southwest.17

While Ellison sold gins as far away as Mississippi, he probably did most of his business within a thirty- or forty-mile radius of Stateburg. The first Ellison gin for which there is a record traveled only a few miles south from his shop to Mrs. Rebecca Singleton’s plantation, an easy wagon trip down the old King’s Highway.18 Mrs. Singleton purchased the new gin in 1825, three years after Ellison bought his shop lot from General Sumter. Exactly when Ellison built his first gin in Stateburg is unknown, but his 1817 advertisement suggests he had the necessary equipment within a year after he became free. Having a shop must have made it easier to use his tools and lay in a store of the necessary iron, lumber, leather, bristles, and other materials. But the new shop did not cause Ellison to neglect his repair business. Between 1822 and 1825, for example, he completed more than $100 worth of repair work for John and Richard Singleton.19

Ellison’s pursuit of new business included advertising his gins and services in local newspapers. Beginning in February 1817, with his notice in the Camden Gazette, he probably advertised continuously until the Civil War. However, because of breaks in the files of extant newspapers, the next surviving advertisement appeared in June 1832 in the Sumter Southern Whig. There he announced that he “manufactures, and has consistently on hand, Cotton Saw Gins of the most approved construction,” and he emphasized his particular model, with its hand-forged saws and hand-filed teeth. Should a planter not want one of the ready-made gins available in his shop, Ellison promised to “make to order, upon short notice, any description that may be required.” Ellison also accommodated cash-strapped planters, declaring that he sold gins “for cash or approved credit, upon very liberal terms.”20 He was eager for business, would do custom work quickly, and was ready to extend credit. None of his advertisements, including notices in the Sumter Gazette, Sumter Banner, Black River Watchman, and other papers, ever mentioned that he was a man of color.21 He was just a gin maker by the name of William Ellison, silently exploiting the colorless name “William.”

Although not as rare as abolitionists, ginwrights were scarce in antebellum South Carolina. According to the 1860 census, there were only twenty-one gin makers in the entire state.22 Five of them worked in William Ellison’s shop, all members of his family. Still, Ellison never lacked local competition. When he first arrived in Stateburg, Camden had two businesses listed as “gin making, carpentry,” and a decade later it still had one.23 In the late 1840s R. C. McCreight, a Camden ginwright who probably was a relative of Ellison’s white mentor, advertised in Sumter newspapers, but by the 1850s his advertisements disappeared.24 Closer to home, Sumterville twelve miles to the east also housed competitors. In the 1840s Hudson and Brother advertised gins “not surpassed by any made in the State.” Their gins, they claimed, “possessed refinements” such as “the Falling Breast and Sliding Ribs, which save a great deal in the way of repairs.”25 Hudson and Brother continued throughout the 1840s, but late in the decade they advertised their skills as cabinetmakers, indicating perhaps that their gin business had slumped.26 Another challenger, James S. Boatwright, had a shop in Columbia twenty-five miles to the west. Boatwright competed with Ellison in the field, not just in the newspapers. Between 1845 and 1852 he serviced the gins of Richard Singleton, a valuable account that had previously belonged to Ellison. For Singleton’s repairs Boatwright received $338.27

Spurred perhaps by Boatwright and other rivals, Ellison began to run a different advertisement in the late 1840s. His gins, he announced, were constructed on “the most improved and approved plan, of the most simple construction, of the finest finish, and of the best materials.” He noted particularly that his gins had “Steel Saw[s] and Steel plated Ribs, case hardened.” He also advertised the reasonable price of $2 per saw for his new gins. In addition, he actively bid for repairs, noting that he “repairs old Gins and puts them in complete order, at the shortest notice.” And he promised, “All orders for Gins will be promptly and punctually attended to.”28 Ellison ran this notice throughout the 1850s. The only modification was his claim that cotton ginned on one of his gins “of the late improvement” was “worth at least a quarter of a cent more than the cotton ginned on an ordinary gin.”29 That was a substantial boast, for Ellison was saying that a planter who purchased a fifty-saw gin from him for $100 could expect the gin to pay for itself by ginning only 100 bales of cotton, about 40,000 pounds, less than a single year’s crop for many Sumter planters.

Although Ellison competed successfully, he never achieved a monopoly of the local market. By 1860 three new gin makers advertised in the Sumterville newspapers. John H. Husband of Florence in Darlington District offered gins at $2.50 per saw, while J. N. Elliot of Winnsboro promised gins at Ellison’s price of $2.30 As early as 1853 a gin maker in distant Columbus, Georgia, also sought business in Ellison’s back yard.31 Sumter planters always had these and other alternatives to Ellison’s services. Gins were indispensable, but the free colored gin maker was not. To survive as a ginwright Ellison had to offer the best possible product, which meant constant attention to maintaining and improving the quality of his machines. Tradition has it that Ellison received a patent for some feature of his gin, but existing patent records do not confirm that rumor.32 Certainly by the 1830s Ellison replaced the standard iron saws and wooden ribs in some of his gins with the steel saws and steel-plated ribs that he later incorporated in all his machines.33 Only a few years earlier James Boatwright had to turn down orders because his gins did not include steel saws.34 In addition to gins of the highest quality, Ellison had to offer his customers reliable, speedy service and easy credit. He had to give planters no reason whatever to reject his gins because they were made by a free person of color. Ellison’s record makes clear that he succeeded on all counts.

To prosper, he may have had to be more accommodating to planters than his white competitors. Ellison evidently did most of his work on credit. When he died, many of the leading planters in Sumter District had unpaid accounts, and more than a few had personal notes out to him.35 As a free man of color he probably could not press the planters very hard, and he certainly could not insist they pay promptly. Judging from the accounts of his estate, he kept careful records and simply persisted in his attempts to collect from his customers. He reminded them of their accounts, but he usually waited until they decided to settle up. Sooner or later most of them did, when they had ready cash and were prompted by their sense of fair play, their knowledge of the law, or their desire to maintain access to Ellison’s services. In good years, planters paid Ellison for the year’s work soon after their cotton crop sold. On January 24, 1824, for example, the executors of the estate of John Singleton paid Ellison $70 cash for work he did the previous September.36 But some planters paid with promissory notes, not cash. Early in 1848 R. R. Spann gave Ellison his note for $72.61 for work Ellison completed in 1847.37 Ellison signed Spann’s note and turned it over to Dr. W. W. Anderson in partial payment of his medical bill.38 Dr. Anderson often paid his bills for Ellison’s gin services by providing medical care in exchange.39

Ellison sometimes found it difficult to collect, whether in cash, notes, or services. It is impossible to determine if he had more trouble collecting than white tradesmen, for planters were notoriously slow to pay creditors, regardless of their color.40 John W. Buckner, Ellison’s grandson who worked as a gin maker, often traveled the neighborhood with a fistful of unpaid bills. At least once he returned without collecting a dime. “John went over the river yesterday,” William Ellison wrote his eldest son in March 1857. “He saw Mr. Ledinham. He said that he had not sold but half of his crop of cotton and had not the money but when he got the money and was working on this side of the river that he would send his son with it and take up his account.” That same day Buckner had no more success on the eastern side of the Wateree. He “also saw Mr. Van Buren and he was ready to pay but before he did so he wished his overseer to certify it. But John could not find him and, as it became late, he had to leave for home….”41

Some planters refused to pay at all. To collect from them Ellison turned to the courts. He did not appear in court often, but he made the twenty-four-mile round trip to Sumterville when necessary. In 1834 the judge of the Court of Common Pleas returned a judgment against William H. Killingsworth for $112.50, a debt he had owed Ellison for a year.42 Nine years later Ellison secured a judgment against Oran D. Lee for $110, plus interest, for a forty-saw gin Lee had ordered more than two years earlier.43 Clearly Ellison’s work was not over when he built and delivered a gin. Collecting his debts also took time, energy, and, perhaps even more, finesse.

An eyewitness account of Ellison’s gin operation was left by Thomas S. Sumter, General Thomas Sumter’s great-grandson, who grew up in Stateburg before the Civil War. Sumter remembered that the “frame of the gin, that is the wood work, was made in their work shop by hand, mostly out of white oak, hickory and pine grown on their own lands.” The Ellisons “turned and grooved it by hand,” he recalled. The “saws that cut the cotton from the seed were made and tempered at their blacksmith shop, and the teeth on them made with a file by hand.” Sumter declared that while William Ellison trained his slaves to do the tedious work of filing the saw teeth, the Ellisons did the “delicate work with their own hands.”44 But the slaves must have done some of the delicate work too, for in the 1820s Ellison claimed that a slave gin maker he owned was worth $2,000, far more than the price of a rough carpenter or blacksmith.45 At rimes there was apparently more delicate work than even the Ellisons and their skilled slaves could perform, for Ellison employed at least one free Negro gin maker in 1850, an A. Miller who lived with Ellison’s son Reuben.46 Another free man of color, Hale Johnson, a cabinetmaker, may have also worked in Ellison’s shop in 1850, since he lived adjacent to the Ellisons.47 By 1860, however, both these free men of color were gone, suggesting that by then Ellison’s family and growing slave force could handle all the work themselves.

Ellison’s gin shop also did general blacksmithing and carpentry. No more free from pesky competition in this line of work than he was in gin making, Ellison still enjoyed a brisk local trade. Work done for the Moody family, a large and sometimes rowdy clan of white planters and overseers who lived just north of Stateburg, illustrates something of the diversity of Ellison’s operation. Between 1833 and the Civil War, blacksmiths in the Ellison shop made the Moodys’ horseshoes, hinges, bolts, nails, hooks, rivets, hoops for tubs, and trace chains. Carpenters built coffins (two for Moody women and several for their slaves), repaired chairs, and finished a fine mahogany table. Blacksmiths and carpenters worked together to make the Moodys a wagon, skimmer and shovel plows, axes, hammers, pitchforks, well buckets, and wagon wheels. Bills for the work ranged from as little as $4.10 one year to $136 in another. The bills were prepared meticulously by either William or Henry Ellison.48 Unfortunately for Ellison, the Moodys were not nearly so careful in paying them. At least twice Ellison took the Moodys to court, winning judgments of $136 in 1834 and $22.50 in 1860.49 The settlements evidently left no hard feelings, since the Moodys continued to trade with Ellison.

So important were general blacksmithing and carpentry that in 1850 Ellison estimated they brought in one-half of his shop’s income, about $1,500 of an annual revenue of $3,000. The remaining $1,500 came from the gin business, about $1,000 from the manufacture of approximately fifteen gins during the year and the other $500 from repairs.50 Except for these rough estimates in the 1850 census, there are no records with which to calculate the volume of business done at Ellison’s shop or the income he received from it. Most likely his business grew gradually as his reputation attracted more and more customers and as his expanding labor force allowed him to accept more orders.

FROM the 1820s until the Civil War, Ellison’s gin shop anchored his economic life. It produced a steady, predictable source of income from which he extracted continuous profits by employing his family members and exploiting his slaves. Without slaves, Ellison could have aspired only to the income of a tradesman, at best a modest existence that promised little security for his family. With slaves, he soared into strata occupied by no other free Afro-American in South Carolina and by only a few whites. Each acquisition of a slave man brought Ellison immediate financial rewards by permitting him to build and repair more gins, to increase his profit margin, and to squeeze the surplus from one more worker. Profits from his gin business allowed him to become a landowner and eventually a planter. William Ellison’s fortune derived from his own hard work and that of his family members, but most of all it came from his slaves.

The growth of Ellison’s slave force cannot be charted through legal documents as it can for most whites. White planters routinely recorded the purchase or sale of slaves with the court as insurance against later claims, commonly made, that the transaction was somehow imperfect or incomplete. Ellison evidently never registered any of his slave purchases. If he had followed the conventional practice and insisted on registering a purchase, he might have offended the white seller, calling into question the individual’s honesty and integrity. The absence of court records of Ellison’s slave purchases is an index to Ellison’s dependence on the good will of local whites. Ellison did not simply overlook recording his purchases. He understood how to use the courts, he had access to good white lawyers whom he retained when necessary, and—when it was essential, as it was with land—he saw to it that his transaction was thoroughly documented in official records.

Without bills of sale, evidence for the growth of Ellison’s slave population must be gleaned from the federal census. The census contains only meager information about Ellison’s slaves—their sex, age, and color—and that only at ten-year intervals.51 Changes that inevitably occurred between visits of the census marshall may be invisible. If a slave died or was sold, and if Ellison replaced him or her with a slave of the same sex and approximately the same age, the census will not reveal it. Because the census often obscures the churning that took place among Ellison’s slaves, our estimates of the number of purchases he made are conservative, the smallest number that can account for the total in the census from decade to decade. Despite its limitations, the scanty evidence in the census suggests Ellison’s strategy in building his slave force.

In 1820 Ellison owned two adult men, both between the ages of twenty-six and forty-five.52 Except for those moments when Ellison was arranging business with planters or gathering his supplies, he could have been found working shoulder to shoulder with his bondsmen. Business was good during the 1820s, and not even three men could keep up with it. Since Ellison could not hire white men to work under him, he augmented his labor force with apprentices who, like his slaves, worked for the right price—nothing. A master who wanted a young slave trained as a blacksmith or carpenter sent him to Ellison. In 1822 Ellison paid a Sumterville lawyer $5 for drawing up papers for an unknown number of apprentices.53 Four years later Ellison paid Dr. W. W. Anderson $2.50 for treating Judge Thomas Waties’s “boy,” indicating that the slave was temporarily in Ellison’s charge, probably as his apprentice.54 When business was particularly brisk Ellison also hired slaves, as he had before he owned any of his own. In 1825, for example, he gave Dr. Anderson a dollar a day for each of two slaves he employed for fifteen days.55

Ellison resorted to apprentices and hired labor because the growth of his business outstripped his limited supply of labor. But apprentices and hired hands meant he depended on transient helpers of varying levels of skill and little training or experience as gin makers. Ideally he would have owned enough slaves to run his shop, slaves he could train methodically and control permanently. Accumulating the capital to buy slaves in the 1820s was difficult, however. He had a wife and four small children to support, and none of them could be of much help in the gin shop. Nevertheless, during his first decade of freedom, Ellison purchased his expensive acre from General Sumter, built and equipped his shop, and somehow managed to buy two more slaves, one man between the ages of ten and twenty-three and another twenty-four years old or over.56 Presumably Ellison wasted no time putting these men to work in his business, which continued to expand during the 1820s.

Ellison began the 1830s with four slave men, all working in his gin business. Early in the decade he tapped a new source of labor, his sons. Henry turned fourteen in 1831, William Jr. in 1833, and Reuben in 1835. Having three sons was a stroke of luck for the ambitious ginwright, and he saw to it that they learned the trade helping him in the shop, just as he had spent his early years in McCreight’s shop. By 1836 Henry, 19, began to assume some special duties, like preparing the shop bills.57 While valuable, the labor of his sons did not meet Ellison’s needs, and he continued to take on apprentices. In 1832, for example, he paid the medical bills of two slaves who belonged to white men.58 The labor of his sons and apprentices could not compare, however, with that of his slaves. By the end of the decade Ellison owned thirty slaves, twenty-six more than he had in 1830, a spectacular increase of 750 percent.59 During the 1830s he kept his gin shop in good order, established a solid reputation as a master craftsman, and the work poured in. His profits skyrocketed. Like his planter customers, Ellison invested his income in labor, gambling that it would multiply his future earnings.

During the 1830s Ellison dramatically changed his strategy for acquiring slaves. Previously he had only purchased slave men, who paid immediate dividends in his gin business. When he was just getting started and was short on capital, he wanted quick returns on every investment. But by 1840 he owned nine female slaves. Judging from their ages, Ellison probably bought six women, all but one or perhaps two of them in their fertile years. As a result, Ellison owned slave children for the first time, three girls and five boys under ten years of age. By 1840 he also owned sixteen other male slaves, indicating that he had purchased at least six more men between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-six and four more between the ages of thirty-six and fifty-four. By 1840 he had sixteen male slaves ten or older, old enough to work.60

Ellison’s decision to buy females was a sharp departure from his previous pattern, but it probably did not represent a change in his primary objective—to acquire labor for his gin business. Although slave women did not work as mechanics, they could and did produce slave children, and the boys at least could become artisans in Ellison’s shop. Like white planters, Ellison evidently understood that natural reproduction was a less expensive way to increase one’s slave holdings than buying in the marketplace. By acquiring slave women, Ellison adopted the traditional economic strategy of antebellum planters, and, judging by the eight slave children he owned in 1840, it worked. Ellison’s decision to sacrifice short-term gain for bigger dividends in the long run reflected his confidence that he had found his place in Stateburg and his intention to sink roots that would nourish his family for generations.

If Ellison’s slave women did not work in his gin business, what did they do between births? During the 1830s Ellison began to buy land, most of it fields that provided work for his slave women. In 1835 he initiated the purchase of a home and 54½ acres that belonged to Stephen D. Miller, a Stateburg lawyer and former governor of the state who had decided to move his family to Mississippi. For the sum of $1,120 “paid me by William Ellison, gin maker,” Governor Miller sold his home that stood about 150 yards south of Ellison’s shop and his land that lay just across the Columbia-Sumterville Road to the west. Ellison bought the Miller property on credit, completing the transaction in November 1838.61

He also purchased two larger tracts of land during the 1830s. Both came from the Sumter family, from whom he had bought his original acre. Throughout much of the antebellum period, severe financial distress forced the Sumters to sell off large portions of their vast land holdings. In a transaction he began in January 1833 and completed in July 1838, Ellison paid $581.50 for 65½ acres.62 The price of about $9 an acre was typical of good farm land in the area. At the end of the decade Ellison bought “Davis Hill,” paying the Sumters the huge sum of $5,000 for a parcel of 216 acres.63 There may have been a dwelling on the property, which could help explain the price of more than $20 an acre.64 Both tracts—which were just north and east of his shop at the crossroads—abutted his other property.

By 1840 Ellison owned a home, a gin shop, thirty slaves, and more than 330 prime Sumter District acres. No longer just a tradesman in business for white planters, he was becoming a planter himself. Diversifying into agriculture no doubt created headaches for Ellison, but his farming complemented his manufacturing. Owning land as well as a gin business meant that Ellison had productive work for all his slaves, regardless of sex. In general, the men worked in the shop, the women in the fields. In 1840 eleven members of the Ellison household, mostly female slaves, worked in agriculture.65 In the same year twelve members of the household, more than half of them slave men, worked in “manufacturing and trades,” making Ellison’s shop the second largest manufacturing concern in Sumter District.66 Male slaves produced a substantial income for Ellison in the shop. Female slaves grew provision crops that allowed Ellison to feed from his own fields the more than three dozen persons dependent on him. His slave women also grew cotton, which in time became a major source of income.

A dual career in agriculture and manufacturing gave Ellison flexibility in the use of his slaves. He could assign to his gin shop only those men who showed a talent for mechanical work. The rest he could send to the fields. Certainly a few of the eleven individuals he employed in agriculture in 1840 were slave men. Ellison also was in the enviable position of being able to shift his slave men between agriculture and the gin business according to the seasonal demands of the crops and the pace of business in the shop. Slaves in the shop did not lack for work just because planters temporarily had no need for new gins or repairs. Shop mechanics built gins ahead of demand and had them ready for eager customers.67 Unlike the gin trade, the blacksmith and carpentry work was fairly steady month to month. Even if there was little work of any kind in the shop and it was lay-by time in the fields, Ellison still had an option. From time to time he hired out his slave men to local planters who needed skilled labor. In 1845, for example, one of the Moody clan hired Carlos, and although the bill did not specify the nature or duration of his work, Ellison received a payment of $5.12½.68

In the 1830s Ellison’s economic operations achieved a pattern that remained unaltered for the rest of his life. Agriculture and manufacturing meshed effectively, and the combination permitted him maximum exploitation of his labor. With three arenas for productive work—his gin shop, his fields, and neighboring plantations—Ellison’s slaves, particularly the men, probably enjoyed even less leisure than most slaves, who enjoyed precious little. The efficiency of the entire operation was greatly increased by Ellison’s cautious expansion. He bought no more land than he could use and never before he had sufficient labor to take full advantage of it. Unlike many white planters, Ellison was no land speculator. He benefited in fact from the reverses of one of the area’s largest speculators, General Thomas Sumter. Most of Ellison’s land came from the general’s heirs, who were forced to sell off in their effort to brake their downward economic spiral. Ellison acquired his land over a period of three decades, and once he purchased a tract he never sold an inch. He chose each parcel carefully, buying property only in proximity to the crossroads. Unlike Richard Singleton and other white grandees, Ellison did not have to leave home and ride for days to supervise a sprawling estate. Conservative expansion, along with efficient integration, tight concentration, and direct supervision, increased the probability that Ellison earned the highest return on every dollar he invested.

WILLIAM ELLISON, gin maker, slaveholder, shop owner, and planter, had a private life as husband, father, and family man. His foremost concern was the preservation and extension of his family’s freedom. The same unremitting attention, deliberate planning, and steely discipline he displayed in his economic life he also applied to familial matters. Unlike the families of slaves, his family had a legal reality. Unlike the families of the white planters he served, his family’s freedom was not guaranteed. Ellison did all he could to assure that whatever respect and acceptance his economic activities could wrest from white society would accrue to his family.

All families are guardians of human survival, but for William and Matilda Ellison the role of guardianship took on special meaning. In addition to the traditional duties of procreation, nurturing, training, and care, these parents had to prepare their children for life in a society in which color and caste predominated.69 In the antebellum South, race was no fuzzy theory they could push aside and ignore. It impinged on every facet of their lives, including family relationships. For all Southerners, historian Bertram Wyatt-Brown has observed, the “inner life of the family was inseparable from its public appearance.”70 This was particularly true for free Afro-American families who aspired to prosperity and respectability. In the Ellison household, private details of family life were dictated by the need to protect family members from an intrusive, potentially dangerous white society.

Patriarchy structured families throughout the nation in the antebellum years. Southern planters idealized patriarchy as the basis of their authority over their slaves and within their white families.71 William Ellison had more reason than white planters to act the patriarch. All Southerners were required to take into account community standards of conduct. White communities expected free Negroes in particular to hew to the straight and narrow, and they permitted swift correction of those who strayed. Communities judged entire families by wayward individuals. A single important misstep by an Ellison could undermine the whole family’s respectability. As long as family members remained within the orbit of his power, William Ellison compelled them to behave according to his perceptions of the requirements of the white community.

Compared to most Afro-Americans, the Ellisons had privileged lives. But being an Ellison also had its cost. Precisely because so much was at stake, family members forfeited their autonomy and individualism to William Ellison’s authority and control. Ellison’s economic achievement was so conspicuous that family members could not avoid white scrutiny. Each day, traps and snares awaited a slip by one of the Ellisons. To skirt them successfully—in the shop and fields, at church, on neighboring plantations, in factors’ and merchants’ stores in Charleston, in the courthouse in Sumterville, and on the roads and trains—the Ellisons had to be surefooted and nimble. The social terrain in the High Hills shifted from decade to decade. By monitoring his family’s behavior as closely as the quality of his gins, William Ellison succeeded in creating a haven in Stateburg. His most important legacy to his family was not the gin business or his slaves, for in time they disappeared. It was not his land, enduring as it was. His most valuable legacy was his good name, the respect he earned in his four and a half decades in Stateburg. His good name outlived him, and long after he was gone it continued to sustain and protect his family in an increasingly harsh and dangerous South.

Eliza Ann, the first of April and Matilda’s children, was born in 1811 and lived in bondage until 1816 (or shortly thereafter). Little is known about Eliza Ann’s childhood and youth, but it is certain that her early years bore little resemblance to the lives of the young daughters of the planters for whom her father worked. Life in the Ellison household in the 1820s must have been a pinchpenny existence, while the aspiring tradesman scrimped and saved to buy his slaves and land, to build and equip his shop, and to provide a home for his growing family. The luxuries common at “Deer Pond,” “The Ruins,” “Borough House,” and “San Souci” did not exist at the Ellisons’.

Whether Eliza Ann received any formal schooling is unknown. She could read and write, and as an adult she kept up with the Charleston newspapers.72 There were schools for free people of color in Charleston, but it is doubtful that in the 1820s her father felt he could afford them, even if he accepted the wisdom of investing scarce capital in female education. Most likely, Eliza Ann learned what she knew of reading and writing at home. Whether her mother could have taught her is unclear, for no record by Matilda’s hand has survived, and it is not certain she was literate. If William Ellison chose to do so, he could have taken spare moments in the evening or on Sundays to teach his daughter.

White girls in the homes of the local gentry had the advantage of formal education. Increasingly concerned about preparing their daughters for suitable matches, planters either sent them away to school or employed governesses to teach them at home. In 1835 Stephen D. Miller, whose Stateburg home William Ellison bought, sent his daughter Mary Boykin to Madame Ann Marsan Talvande’s boarding school in Charleston.73 But some white families concluded mat “schools in Charleston at this time are in low estimation,” and made the often painful decision to send their daughters farther from home.74 A particular favorite of High Hills aristocrats was Mrs. Aurora Greland’s fashionable school in Philadelphia. There the girls’ training consisted more of learning to be ladies than scholars. When a breath of scandal touched the school in 1830, Mrs. Rebecca Singleton, whose daughters Marion and Angelica were enrolled, quickly announced that “Father and myself request Mrs Greland to trust you as little as possible from under her eye.” To soften the blow she included for each daughter $30 for jewelry and $20 “pocket money.”75 Years later, when Marion married and had children of her own, she chose to educate them in her High Hills home. In 1844 Gabriella Huger congratulated her on her decision to hire a governess, adding, “What a comfort it must be to you to have your children educated under your own eyes, and to have them with you always, instead of sending them off to school.”76 Eliza Ann Ellison probably stayed home too, but she did not receive her instruction from a governess.

Eliza Ann’s other youthful activities no more resembled those of her white contemporaries than did her education. She doubtless spent most of her time working alongside her mother, cooking, cleaning, doing laundry, tending the garden, raising poultry, caring for her three brothers (who were six, eight, and ten years younger), and performing the tasks that fell to antebellum women without domestic servants. By contrast, a young white girl stuck in an upcountry village because her father decided not to winter in Charleston, as was his habit, complained of nothing to do. There were “gentlemen” in the village, she admitted, but “no beaux.” The two ladies she visited were married, and thus she expected only to become “versed in the management of chickens and children….” She devoted her mornings to reading, sewing, and a little practice on the guitar, her afternoons to walking, riding, or bowling, and “visiting and talking scandal of course occupy most of our evenings.” While it was a “very delightful village,” she yearned for promenades on Charleston’s Battery.77 Whether Eliza Ann visited in the homes of neighboring free Negroes or found time to gossip and make trips to the coast is doubtful. Unlike her white neighbors, Eliza Ann spent her youth preparing for her future responsibilities as wife and mother.78

About all Eliza Ann had in common with local white girls her age was Sunday morning services at Holy Cross Episcopal Church. Each Sabbath, William and Matilda probably made sure that their adolescent daughter was well scrubbed, her dress pressed, and her deportment equally presentable so nothing would give the white parishioners who undoubtedly stole occasional glances over their shoulders any reason to question the wisdom of permitting the colored family to worship on the main floor. The services evidently moved Eliza Ann, for she remained an active, devout Christian throughout her life. Although she did not mingle with the white girls after the service, her behavior was probably as modest, reserved, polite, and ladylike as theirs.

On May 13, 1830, when Eliza Ann was nineteen, she married Willis Buckner in a service in the Holy Cross Church.79 Her church wedding, conducted by the resident pastor, Augustus L. Converse, suggests that the Ellisons had come far in their quest for respectability, that Eliza Ann had performed her part well and had not been found wanting in the eyes of Stateburg’s best people. No evidence exists of the couple’s courtship, but Eliza Ann certainly could never have boasted as Marion Singleton did in 1839 that “so far we have had a houseful of agreeable company—and at one time I could muster 9 beaux all staying in the house at the same time.”80 Virtually nothing is known of Eliza Ann’s husband. There is no doubt that Willis Buckner was a free man of color. However, the censuses of 1820 and 1830 list no free people of color named Buckner in South Carolina, North Carolina, or Georgia.81 Whether William Ellison considered Willis a “good choice,” as Mrs. Greland of Philadelphia described Brazilia Sumter’s new husband, is unknown.82

On January 23, 1831, exactly thirty-six weeks after their wedding, Eliza Ann and Willis Buckner had a son, John Wilson Buckner.83 The new parents probably lived in the Ellison household, but within the year Willis Buckner died.84 A widowed mother at the age of twenty, Eliza Ann returned to the familiar routines of her youth. Living as she always had, she apparently helped her mother with the housework and the rearing of her brothers and her own infant son. Reuben, her youngest brother, was almost ten when his nephew was born. John Wilson remained the only small child in his grandfather’s house for the first fourteen years of his life. Until the mid-1840s, moreover, Eliza Ann and Matilda were the only free women in the Ellison household. Circumscribed by their race and by a masculine world, they were probably even more confined to the family circle than white women. Visiting, parties, sewing circles, associations, Sunday School—all the occasions that helped white women break out of their domestic isolation—were unavailable because the Ellisons were Negroes.85 In addition, there were no relatives in the neighborhood during the 1830s, no sisters, aunts, nieces, or cousins to include in a female circle. The relationship between Eliza Ann and her mother was probably strengthened by their living arrangements, common domestic tasks, and isolation. Eliza Ann continued to attend church with her parents, and in 1840 she and her mother stepped forward together to be confirmed in Holy Cross, attesting to the bonds between them.86

Unlike their sister, Henry, William Jr., and Reuben Ellison were born free.87 Their father may have greeted their births as one upcountry gentleman did the arrival of a male child in the home of a Sumterville friend. “I am very glad to hear that the stranger is a son,” he declared in 1825. “Boys can take care of themselves; girls are too helpless.”88 Eliza Ann was no invalid, but she could never grow up to work in her father’s gin shop. Master of just four slaves in 1830, Ellison no doubt looked forward to the labor of his three young sons, and he demanded it when they were of age. Like their father, the Ellison boys grew up around a gin shop, learning the intricate skills of gin making. Through the business, which entailed trips to various plantations, they became acquainted with the physical geography of Sumter and adjacent districts. They also learned to traverse the area’s somewhat trickier social terrain. William Ellison instructed his sons in the behavior, habits, and demeanor whites demanded of free Negro artisans.

The early years of the Ellison boys, like those of their sister, did not look much like the childhood of local white boys. Scions of planter families often enjoyed leisurely, extended adolescenses, filled supposedly with reading, traveling, and general cultivation of the higher faculties, all designed to ingrain the manners, bearing, and polish they would need when they eventually assumed their proper stations. To the consternation of their fathers, however, maturing sons often drifted into lazy, dissolute habits, spending their time racing horses, hunting game, fighting gamecocks, playing cards, and drinking wine.89 While the sons of white planters played, the Ellison boys worked. Rather than enforced idleness, Henry, William Jr., and Reuben learned discipline, industry, and responsibility. Ellison knew his sons’ future did not depend on inherited status or gentlemanly airs but on their ability to wield a file, set pig bristles in gin brushes, and hammer out snug-fitting horseshoes. Practical, on-the-job training would teach them skill in the shop and diplomacy in the community. There were no pampered, soft-handed Ellisons, neither men nor women.

High Hills planters regularly provided their sons with extensive formal education. As with their daughters, Louisa Penelope Preston observed in 1835, “Most of our Stateburg & Camden gentry have a proclivity to the North.”90 In the 1830s, James Chesnut Jr. and a number of other local boys attended Princeton University.91 Even when considering preparatory schools, aristocrats tended to look north. Richard Singleton, for example, after being disappointed in his efforts to persuade a certain Virginia family that reputedly was “fashionable, as well as moral and literary,” to send a son to his plantation “to take charge of my two sons and prepare them for College,” bundled young John and Matthew off to a school in New Jersey.92 Both Singleton boys eventually entered the University of Virginia, a Southern institution that attracted several Sumterians, including Richard I. Manning, who lived a few miles south of Stateburg.93 Many young aristocrats treated universities as new places to sow their wild oats. Most Southern colleges and universities annually dismissed a fair number of students for one or another form of “indecency” that came naturally to the headstrong young planters-in-the-making.94

According to local tradition, William Ellison shared the gentry’s proclivity to the North and sent his sons to school in Canada.95 Available evidence neither confirms nor contradicts the story. Ellison’s finances were less cramped in the 1830s than in the 1820s when Eliza Ann was young. He could afford expensive educations, and he was probably more willing to invest in schooling for his sons than for his daughter. All three boys were literate, and it is almost certain they attended school. Henry, the eldest, had an excellent command of written English as an adult.96 William Jr., the middle son, was less accomplished, suggesting that Ellison may have favored his eldest son with a better formal education.97 The boys may have gone to school in Canada, but far more likely they went a hundred miles south to Charleston, where private schools for free people of color were taught by leading free mulattoes like Thomas S. Bonneau and Daniel Payne. Even after South Carolina outlawed schools for free Negroes in 1834, several continued to operate, quietly teaching the children of the free colored elite.98 If the boys did go away to school, it was not for an extended period, making Canada less likely than Charleston. All three were in Stateburg in 1830 and 1840 when the census marshall called, and the medical records of Dr. W. W. Anderson indicate that between 1832 and 1840 none of the boys went more than two years without a visit from the doctor.99

Regardless of their formal training, the three Ellison boys had their most useful teacher at home. Free Afro-American parents, like slave parents, instructed their children in the arts of survival. William Ellison knew that superior mechanical skills meant little without social dexterity. Ellison’s instruction may have resembled the lessons taught by the wealthy white planter James Henry Hammond, in his way another outsider in the upper reaches of South Carolina society. In 1840 Hammond declared that his younger brother could make something of himself if only he displayed “energy, enterprize, and determination.”100 Five years later, he told another younger brother that grit and hard work were not enough. Hammond said he had encountered a raft of problems in rising to “a position to which I had not been bred” and surrounded by “people who looked down on me.” To succeed, he developed certain social habits that he outlined for the edification of his brother. “Unless you fawn & flatter, every one you meet in every grade, you are damned,” he said. “This can be done without degradation. Every man’s vanity & self-love can be touched without any loss of character & dignity.” In Southern society, “Sensible men study to do it handsomely.” The key, Hammond concluded, was to be “conciliating” and to display “politeness & aminity.”101

This litany of advice came from a white man who, through marriage and hard-driving management, had become one of South Carolina’s richest planters and, just before delivering this homily, had concluded a term as governor of the state.102 Viewed from William Ellison’s social stratum, James Henry Hammond was a silver-spooned, blue-blooded aristocrat. Ellison knew at least as well as Hammond that “sensible men” study humankind, especially the aristocratic species native to the High Hills. As much as Hammond, Ellison ordered his life according to a self-conscious design, and he was not backward in demanding that his sons adhere to it. Fathers in the antebellum South regularly bombarded their sons with advice, but whether Ellison lectured pompously like Hammond or taught silently by example is not known. However he taught, he demanded that his sons acquire the habits of deference, tact, and circumspection they needed to elicit the respect and patronage of white planters. By every measure, Ellison proved a more effective teacher than Hammond. The master of “Redcliffe” constantly found fault with his sons’ lackluster performances. Ellison’s sons learned their lessons.

Just as the sons were creatures of their father’s drive and ambition, the father’s success was in some measure the creation of his sons. During the 1830s all three sons began to pull their weight in Ellison’s business. Henry turned eighteen in 1835, William in 1837, and Reuben in 1839. Ellison integrated each of them into the family economy as gin makers. The 1830s were years of enormous expansion in Ellison’s business, and his three sons made important contributions keeping up with the work in the shop, supervising slaves, making repairs in the field, procuring raw materials, tallying accounts, and chasing down customers who had not paid their bills.

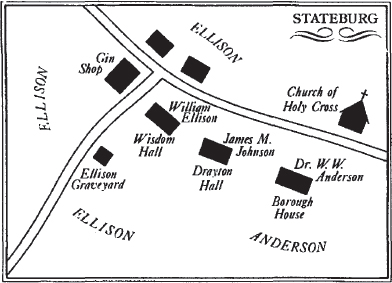

Each day Henry, William Jr., and Reuben worked under their father’s direction, and each night they slept under his roof. Before 1835 the Ellison home was probably a cabin attached to the gin shop on the solitary acre at the crossroads Ellison bought in 1822. Sometime between 1835, when Ellison contracted to buy 54½ acres from Stephen D. Miller, and 1838, when he recorded the deed, the Ellisons moved into a fine house.103 The Miller land included Miller’s home, which stood just south of Ellison’s shop and a few hundred yards north of the Anderson’s magnificent Borough House. What made the acquisition remarkable was not just that it was the home of a white man but that it was the home of one of South Carolina’s most illustrious citizens. Miller had served in the South Carolina legislature and the United States House of Representatives and Senate and, while a resident of Stateburg, had been inaugurated governor of the state. In 1823 Miller and his wife Mary Boykin had a daughter, Mary Boykin Miller, born a few miles north of Stateburg at the home of her mother’s parents.104 Mary Boykin Miller ultimately married James Chesnut Jr. and became the South’s most famous diarist of the Civil War.105 She evidently spent several years of her girlhood in her father’s Stateburg home, while the Ellison boys were growing up nearby. Mary’s playmate was Dr. W. W. Anderson’s son Richard, who won fame during the Civil War as “Fighting Dick” Anderson. Mary Chesnut later remembered that her mother’s personal servant married an Anderson slave, a match eased because the “Anderson house was next door.”106

Stephen D. Miller’s decision to sell his Stateburg land and home to Ellison must have been based on his estimation of Ellison’s ability to pay and on his knowledge of the artisan’s good standing in the community.107 Ellison’s decision to buy rested on similar economic and social considerations. The price of $1,120 was steep, but by the mid-1830s Ellison could afford it. Still, without confidence that the white people of Stateburg would approve, neither Miller nor Ellison would have entered the agreement. Ellison would never have risked the purchase if Stateburg whites considered it arrogant or presumptuous. Both Miller’s decision to sell and Ellison’s to buy confirmed the ginwright’s economic and social achievement in two decades in the High Hills.

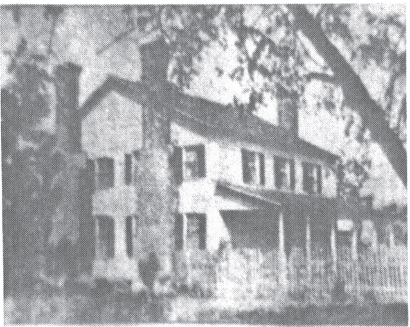

Set back from the southwest corner of the intersection of the Columbia-Sumter and Camden-Charleston highways, the house was clearly visible to all who passed. Travelers may have paused and taken notice of the celebrity of its former owner or the color of its new residents but not its architectural elegance. The large two-story frame structure was not ostentatious. Soaring white pillars would have strained Ellison’s pocketbook and white Stateburg’s tolerance. One local historian claimed the house was built before 1760, but another, noting its “Hand wrought hinges, hand made nails, wainscoting of side single boards, small window panes and a narrow central hall,” ventured an origin later in the eighteenth century.108 A broad-roofed porch extended across the entire front of the house, and three evenly-spaced windows opened above it onto the second floor. Four exposed brick chimneys, two at each end of the house, jutted above the roof line and provided a fireplace for each of the eight rooms. When the Ellisons arrived, there were probably four bedrooms upstairs and a parlor, dining room, living room, and perhaps another bedroom downstairs.109 Detached behind the house were a kitchen and several outbuildings. Spacious and comfortable, it was appropriate for a wealthy tradesman and his respectable family.

Within months of recording the deed to the Miller property, William Ellison returned to the Sumterville courthouse to record a second document, one even more important to him than the deed on his property. On July 12, 1838, with Dr. W. W. Anderson certifying that his statements were true, Ellison registered the birthdates of all his children and his grandson.110 The purpose of this seemingly unnecessary act was to establish beyond any doubt that they were all free persons. By recording Eliza Ann’s birthdate and her free status, Ellison documented that she was free before the 1820 ban on emancipation. Her freedom meant that John Buckner, Ellison’s grandson, was born to a free woman and was thus himself free. By recording evidence that his sons were born after their mother’s manumission, Ellison established their free status. The timing of the registrations suggests they were prompted by Ellison’s major land purchases. Taking tide to large tracts of real estate may have impressed Ellison with the need to establish conclusively that his children and grandson were legally free and thus capable of owning and inheriting property. Whatever his motivation, Ellison went out of his way to create a public, legal record that proved his family’s freedom.

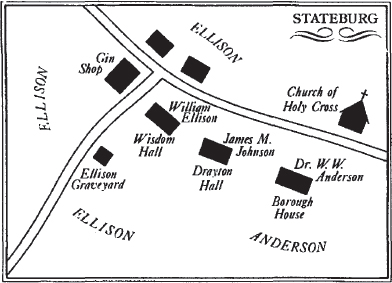

“Wisdom Hall,” the Ellison family home. From The State, October 4, 1931.

THE village of Stateburg and the old cotton country in the surrounding hills tended to cling to the planter families who had been successful in the early years of the cotton boom. Even in the 1830s and 1840s when the High Hills and the rest of the upcountry experienced an exodus to richer lands, individuals left, rarely entire families. The same aristocratic family names that Robert Mills sprinkled over the High Hills in his famous 1827 map of South Carolina persisted decade after decade. The codes, customs, and values that regulated community life were primarily those of the gentry who from generation to generation dominated the political economy of the area. Unified by race, class, religion, economic interests, and over time by blood, planters were the arbiters of community standards and judges of community behavior.

The Ellison family was as rooted as the white gentry. Race set the Ellisons apart from the white community, but they were never insulated from community judgment. Just as individuals were compelled to act within the framework of family obligations, families operated within the web of community control.111 When a white person failed to conform to the will of the community, the miscreant usually tarnished the family reputation and brought its social standing down a peg or two. More was at stake for the Ellisons than admission to the sitting rooms of the leading white families. Community disapproval could destroy all the Ellisons had built. Without patronage the Ellisons could not work in Stateburg. Withdrawal of their welcome also meant loss of protection from those willing to light the firebrand and knot the lynch rope. Ostracism was tantamount to banishment, and neither was a mere hypothetical threat. In 1860 the Ellisons received a letter from a free man of color named Jack Thomas, who had left Stateburg seventeen years earlier for Central America. “It seems as there has been a curse upon us ever since we left home,” he declared. “I wish I was back home,” he wrote. “Would to God I was there now.”112 The reason Thomas was forced to leave the village is not clear, but some serious infraction drove him from the community. One member of the Ellison family recalled that just before he departed Thomas “awakened with the prospect of an abundant final siesta.”113

Even a hawk-eyed observer like William Ellison could not always be sure of community norms. They were not formulated into rules. White men had to guess and improvise, and sometimes they misjudged.114 Ellison’s social assignment was murkier. Some of the standards that applied to whites—moral uprightness, piety, and honesty—also applied to him. But some traits accounted virtues in whites—manliness and the various assertive manifestations of freedom—were dangerous in a Negro. Moreover, Negroes were held to additional standards, such as humility and deference. White men had difficulty staying on the path to honor and status, but at least others had gone before them and trampled down the grass. Every day William Ellison explored new territory. He was a Negro who worked in a white man’s trade, a former slave who owned more slaves than most white Southerners, an artisan whose wealth dwarfed that of most whites, a man born in the slave quarters who now lived in the home of a former governor.

The Ellisons’ color, status, and eye-catching achievement made them unavoidably conspicuous. Because of the location of their new home, they lived in a fishbowl. The crossroads site was wonderful for business, but it meant that daily life in the shop and fields and on the porch could be observed by peering travelers. Directly across the old King’s Highway from the Ellison home stood a tavern. “It was here the tobacco wagoners, cattle dealers, and travelers from the upcountry on their way to Charleston would meet and rest,” one Stateburg resident remembered, “and all the surrounding country would gather to fight chickens, run race horses, play cards, trade and drink corn whiskey from North Carolina and Virginia, and also fine wines….”115 Public and private life overlapped for everyone in the antebellum South, but the Ellisons were on display constantly, even at home. Self-scrutiny and self-regulation had to become habitual.

In small, stable rural communities like Stateburg, everyone literally knew everyone else. Prying, judgmental neighbors with long memories and short tempers presented free families of color with real dangers. But the human familiarity that permitted community standards to be defined and enforced also protected those who conformed. Historian David M. Potter termed Southern society a “folk culture” characterized by “personalism,” a dense network of human relations, person to person, face to face.116 Direct, personal knowledge of one’s neighbors probably intensified both hatreds and allegiances, but it also accustomed people to take the measure of a man or woman, white or Negro, and trust it more than any abstraction about men or women, whites or Negroes. For free Afro-Americans, this amounted to an opportunity to be judged as human beings, and they seized it. Free Afro-Americans knew white communities could be brutal to those who failed to live up to expectations, while they supported, defended, and rewarded those they found worthy.

Each day William Ellison cultivated personal relations with powerful white men. As long as the Ellisons stayed in Stateburg among people who knew them personally, who valued them and their work, they had all the security the antebellum South offered to free people of color. As he established his reputation in the High Hills, Ellison had advantages few other free people of color could exploit. When he arrived in 1816, he bore the family name of a respected white planter in Fairfield District, and local white people, knowing about such things, probably silently assumed shared blood. When April Ellison took his former owner’s first name four years later, he strengthened that suspicion. The fact that Ellison was a mulatto proved a continuing asset. Most whites were biased in favor of light-skinned Negroes.117 If they had to deal at all with Negroes who were not slaves, they preferred them light. In the long run, however, the bedrock of Ellison’s acceptance was his trade. Any white man who needed a shoe for his horse, a new bucket for his well, or a hinge for a sagging door appreciated the convenience of having Ellison around. The quality of his work and the steady reliability of his service were crucial to the unspoken white decision that he deserved to stay. Every gin saw he forged fastened another link to High Hills planters. Each planter’s promissory note embedded him in the complex system of credit that entangled white men.118 Few colored men could claim as many business relationships with white planters as William Ellison.

Ellison made certain that the white men who came to the gin shop encountered free people of color who measured up. The Ellisons had to master the subtle rituals of racial etiquette in the midst of serious business negotiations. Each Ellison had to be deferential but not obsequious, sensitive to planters’ wishes but not sycophantic, attentive to planters’ demands but not slavishly obedient, ingratiating but not groveling. Aggressive independence and haughty self-assertion would jeopardize planters’ patronage, while bootlicking and kowtowing would destroy planters’ confidence and respect. As black businessmen rather than slaves, correct behavior for the Ellisons lay somewhere in between. Just where, however, must have been difficult to determine. The shop’s prosperity confirms the Ellisons’ ability to find the tightrope and walk it.

Because wealth was generally esteemed and often assumed to be the mark of merit, Ellison’s economic success helped win the respect of the white community. However, in the antebellum South prosperity was reserved almost exclusively for fortunate whites. Each advance by Ellison nudged him farther from most other free Afro-Americans and closer to the white elite, heightening the disjunction between the social connotations of his color and the visible reality of his success. Lesser whites in particular may have viewed his ascent with resentment and jealousy. A former slave on Richard Singleton’s plantation remembered that the overseer there considered slave artisans a personal affront. “Ye think because ye have a trade ye are as good as ye master,” he would scream before whipping them, “but I will show ye that ye are nothing but a nigger.”119 In Mississippi, a dispute over property led a white man to murder William Johnson, the free Negro barber and diarist of Natchez.120 Prosperity had its risks, but it was better than poverty. Poor free Negroes found it more difficult to attach themselves to powerful whites. Ellison’s wealth made it easier for wealthy whites to respect him, despite his color.

The 1822 law requiring each free man of color to have a white guardian formalized the personal relationships between the races. Legislators wanted every free Negro man in South Carolina beholden to some upstanding white man. On January 7, 1828, five years after the law became effective, William Ellison appeared before the clerk of court in Sumterville with Dr. W. W. Anderson. Anderson swore that he had “known William Ellison a free man of colour for several years and believe him to be of good character and correct habits.” Declaring himself a “free holder” in Sumter, as required by the law, Anderson formally accepted the guardianship of the mulatto ginwright.121 Anderson probably knew Ellison as well, or better, than any white man in the High Hills. Since 1822 Ellison’s gin shop had stood within a few hundred yards of Anderson’s “Borough House.” By doing business with each other, the two men developed mutual respect that the guardianship formalized.122

Why William Ellison waited five years to secure a white guardian is unclear. It is unlikely that he was ignorant of the 1822 law. He never lacked sound legal advice on essential matters. His delay probably came from his instinctive caution about entering a binding agreement with a white man that could—if it were with the wrong white man—compromise his newly won freedom. Only six years after he had slipped free from his white master, the law told him to find a white guardian. His caution about making the decision was probably buttressed by a growing confidence that things were working out in Stateburg, a feeling that he could afford to take his time to look over white men just as they were looking him over. By choosing Dr. Anderson, Ellison selected the white man who came to his house frequently on medical calls, who knew his family, who did business with him, and who worshiped in his company each Sunday at Holy Cross.

Whether Ellison ever called upon Dr. Anderson to do anything in his capacity as guardian is unknown. A former slave of John Frierson, whose plantation “Pudden Swamp” was in the eastern part of Sumter District, remembered that his master, a “kind-hearted man,” was “chosen by some of these free colored people as their guardian,” and he “never failed to respond to the call of distress.” All free Negroes, he recalled, “had to have some white man to be their guardian. That is, some white man to look after their interest to see that they got their rights, and to protect them, if necessary.”123 Although the legislature passed the guardianship law to force each free Negro man to find his own personal policeman, free men of color did what they could to twist the law in their favor. They hoped their guardians would instead safeguard them and their interests.

Other Stateburg whites also accorded Ellison the recognition and respect he sought. In an article on the “Governor Miller home” in 1931, the Columbia State reported that “There are many people now living who remembered these [Ellison] gins when in use in every part of this and other states,” and that the gin maker William Ellison “is said to have been a mechanical genius…. ”124 Two decades later, Thomas S. Sumter, a descendant of the founding father of the district, recalled that William Ellison “was well respected by all, and he and his sons patronized for their gins.” He even claimed to remember that every person buried in the Ellison family graveyard had been laid to rest by white “friends” who acted as attendants and pallbearers.125

Contemporary evidence from the nineteenth century confirms these twentieth-century reminiscences. When Dr. Anderson drew up his early accounts for the Ellison family, he sometimes headed them “William Ellison—colored man.” Over the years, he dropped all references to race, and he treated William Ellison and “Mrs Ellison,” an unorthodox appellation for a free Negro woman in the antebellum South.126 In 1838, a Mr. C. Cross presented William Ellison with an expensive three-volume Life of Napoleon Bonaparte, published in 1827 in Philadelphia.127 Although it has proved impossible to identify Mr. Cross, he obviously believed Ellison deserved such a gift and would appreciate good history.

One of the most revealing illustrations of how Ellison operated in the white community comes from the diary of Natalie Delage Sumter. No white family other than the Andersons had a more enduring relationship with Ellison than the Sumters. In 1802 Thomas Sumter, Jr., the general’s son, married Natalie Delage while he was in France on a diplomatic mission. After a tour of duty in Brazil, the Sumters returned to Stateburg to live at “Home House,” the plantation the general gave his son. “Home House” was located two miles from Ellison’s shop, and the ginwright did good business with its owner.128 When Thomas Sumter, Jr., died in 1840, Natalie Delage Sumter took over the management of the plantation. To help order her chaotic life, she began to keep a diary. On July 14, 1840, she made the following entry: “Ellison est venu[;] j’ai arrange mes affairs avec lui. he is a very honest man for he came to tell me about 144d [$1.44?]—that no one knew but him[;] he is to get me 3 locks. I gave him 75 cts.”129 Like a brown Abraham Lincoln, Ellison made a four-mile trip to return a small sum he discovered he had inadvertently overcharged Mrs. Sumter. This particular customer—hassled by unruly slaves and gouged by opportunistic tradesmen—could not have been more appreciative. The story of Ellison’s utter honesty almost certainly made the rounds, for “Home House” was a hub of High Hills society, and Mrs. Sumter was a regular visitor in the parlors of leading citizens.130 Her story probably sparked other ladies and gentlemen to recount their experiences with the remarkable colored man who lived in the Miller house in Stateburg.

ONE important feature of Ellison’s life never entered those cozy conversations among the Stateburg aristocracy. Like so many other free persons of color, Ellison remained tied to slavery by a family member. He had a fifth child, a daughter named Maria Ann, who remained a slave all his life.

On November 17, 1830, Ellison purchased Maria from her owner, Dr. David J. Means of Winnsboro, “in consideration of the love and affection which I have for my natural daughter Maria a woman of colour … with a view to procure & affect her emancipation.”131 Since manumission had been outlawed ten years earlier, Ellison resorted to the legal technique of vesting her ownership in trust to another person. The day after he purchased Maria from Means, he sold her for one cent to Col. William McCreight in Winnsboro, the white man he had served as an apprentice fifteen years earlier. The trust bound McCreight to hold Maria under carefully prescribed conditions: she was to be “allowed to live with William Ellison or whomever he directs”; Ellison retained “the right at any time to emancipate” her in South Carolina or any other state; if Ellison died, then McCreight was to “secure her emancipation as soon as possible here or in another state”; all expenses for these arrangements were to be paid by Ellison’s estate, and his executors were prohibited from contesting this provision and from themselves holding Maria “in bondage”; and finally, McCreight and his family had “no right to the services of Maria during or after the life of William Ellison,” and this was to extend to any children she might have. The trust, in short, allowed Maria to live as a free woman of color, although legally she remained McCreight’s slave.