BY his fiftieth birthday, in 1840, William Ellison had reached a plateau. In the first thirty years of his life, he climbed from slave to master, and in the next twenty years, from master to planter. The owner of thirty slaves, a half-section of High Hills land, a flourishing cotton gin business, and a handsome home, he had amassed an impressive fortune. No evidence directly reveals Ellison’s assessment of his achievement, but it is difficult to imagine that he felt disappointed. In a half-century his efforts had taken him from a starting point below all whites to the economic level of the white ruling class. The pace of his acquisitions during the next two decades leaves no doubt about his unquenched ambition. But as he grew older and his sons came of age, he had to channel more of his ambition through them. Since 1816, his ultimate ambition had been to secure and endow the freedom of his family. His legacy of land and slaves could underwrite the freedom of the second generation of Ellisons, but only the efforts of his children could pass his most cherished possession to subsequent generations.

Between 1844 and 1847, when they were in their mid- to late twenties, Henry, William Jr., and Reuben each chose a bride from a prominent family of color in Charleston. William Jr. probably married first. His new wife, Mary Thomson Mishaw, was nine years younger than he.1 She was the daughter of John Mishaw, a prosperous free mulatto shoemaker who belonged to the Brown Fellowship Society, Charleston’s most exclusive free mulatto benevolent society.2 Henry and Reuben married sisters. Henry’s wife, Mary Elizabeth Bonneau, and Reuben’s, Harriett Ann Bonneau, were daughters of Thomas S. Bonneau, the respected free mulatto schoolmaster and community leader, who was also a member of the Brown Fellowship Society.3 Mary Elizabeth was seven years younger than Henry, and Harriett was probably younger than Reuben, though her age is unknown.4 Through their marriages, the three brothers joined the Ellison family with the brown aristocracy of Charleston.

In the tradition their white neighbors had established a generation earlier, the Ellison brothers married upcountry wealth to tidewater society. As sons of one of the state’s wealthiest free men of color, the Ellisons did not need to restrict their choice of spouses to the few eligible free women of color in Sumter District. The field of choice in Charleston was not only larger, but more fashionable. Although the brothers stood to inherit their father’s estate, red clay probably showed in the stitches of their boots. They lacked the polish, refinement, and cosmopolitan associations an elite spouse from Charleston could bring them. By marrying into established free mulatto families in the city, the Ellison brothers broke out of the social isolation of Stateburg and gained kinfolk among the prosperous mulatto artisans and slaveholders who composed Charleston’s free colored aristocracy. That the brothers successfully courted daughters of the upper crust of Charleston’s Afro-American society suggests how well their father’s wealth traveled.

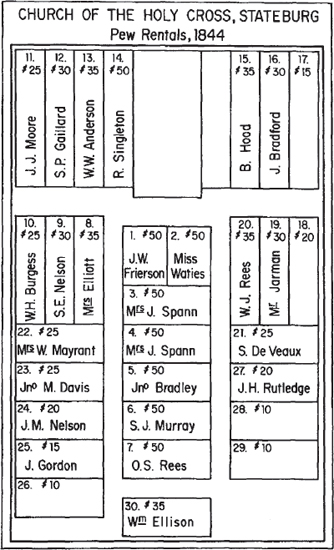

William Ellison presumably gave his blessing to these advantageous marriages, since in all other important matters the sons had to reckon with their father’s wishes. They may also have had to meet certain demands of their brides’ families. Thomas Bonneau and his wife Jeannette and John Mishaw and his wife Elizabeth were active parishioners in St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, a congregation elegant enough, for example, to witness the baptism in 1822 of Wade and Ann Hampton’s son Christopher Fitzsimons.5 When the Bonneaus baptized their own son Thomas Collins in 1814, one of the sponsors was William Pencil, the free Negro man who became an official hero of South Carolina for betraying the Vesey conspiracy.6 The respect accorded the Bonneaus’ piety is evident in their sponsorship of numerous baptisms of free mulatto children in St. Phillip’s. It may well be that the Ellison brothers’ prospective in-laws insisted that the suitors establish their religious credentials before they consented to their daughters’ marriages. In 1843, shortly before the Ellison brothers married, all three were baptised at Holy Cross in Stateburg.7 Two years later, after William Jr. had married Mary Thomson Mishaw, all three of the brothers, their father, and Mary were confirmed at Holy Cross, suggesting that maybe even old William Ellison had to knuckle under to the Bonneaus’ religiosity.8 For a quarter of a century he had faithfully attended services at Holy Cross without stepping forward for confirmation. He and Matilda were baptized together in 1836, and now, nine years later, he made the confirmation of his sons another family occasion.

How the Ellison brothers met the Bonneau sisters and Mary Mishaw is unknown. The brothers may have attended Thomas Bonneau’s school in Charleston and been introduced into free colored society by their teacher. But since Bonneau died in 1831, Reuben was almost certainly too young to have been one of his students. He and his two brothers may instead have gone to Daniel Payne’s school early in the 1830s and made contacts through Payne, who taught several of Bonneau’s daughters.9 Or the Ellisons may have become acquainted with Charleston’s free mulatto families when they came to the city on family business, picking up supplies, looking after the shipment of cotton gins bound for the Southwest, and making certain their father’s cotton was properly consigned to his factors. They may also have come to know the city’s free colored elite through their new brother-in-law, James Marsh Johnson.

On February 26, 1845, after nearly fourteen years as a widow, Eliza Ann (Ellison) Buckner married James M. Johnson, the son of another member of Charleston’s free mulatto elite, James Drayton Johnson, a respected tailor.10 Young Johnson, who was about nine years younger than Eliza Ann, had moved to Stateburg in 1842.11 An experienced, well-trained tailor, he may have learned of the market for hand-sewn fashions among the planters in Sumter from a long-standing friendship with the Ellison brothers that dated from school days in Charleston. It is also possible that William Ellison suggested the move, since the senior Ellison may have been a friend of Johnson’s father as early as the 1820s.12 If Johnson had no previous contact or knowledge of the Ellisons, he surely met them quickly after he arrived in Stateburg, since he was baptized in Holy Cross along with the three Ellison brothers in 1843 and received confirmation shortly thereafter, two years before Henry, William Jr., and Reuben.13 While her brothers evidently married in their wives’ home church in Charleston, Eliza Ann’s wedding took place in Holy Cross, with Reverend Converse officiating again.

Rather than losing a daughter and three sons, William and Matilda Ellison gained a son-in-law and three daughters-in-law. All four Ellison children brought their spouses home to live in their father’s household. They were more than Ellison’s eight-room house could comfortably accommodate. Sometime in the 1840s he and James D. Johnson purchased a frame house about seventy-five yards south of the main residence, possibly as a wedding present for Eliza Ann and James M. Johnson, although the two patriarchs retained ownership of it.14 The house was not a cozy honeymoon cottage, however. In 1850 it housed, in addition to Eliza Ann and James, Johnson’s stepson John Buckner, Reuben Ellison and his wife Harriett Ann, and Peter Turner, a seventeen-year-old free colored tailor who probably worked as Johnson’s apprentice.15 Residing in Ellison’s own house were he and his wife Matilda, Henry and his wife Mary Elizabeth and their three-year-old daughter Matilda, and William Jr. and Mary Thomson and their three children, William John, Henrietta Inglis, and Elizabeth Anna.16 Within the family, the Johnsons’ residence was referred to as “Drayton Hall,” evidently in honor of Eliza Ann’s father-in-law. William Ellison’s home was called “Wisdom Hall.”17

Just as their residences attested to the strength of family bonds, so did the names the Ellisons chose for their children. Between 1845 and 1852 William Jr. and Mary Thomson had five children. Their son William John was named for his grandfathers, William Ellison and John Mishaw. Elizabeth Anna bore her aunt’s name. Another daughter, Henrietta Inglis, was evidently named for Henry and the Inglis family, a free colored family in Sumter District who also attended Holy Cross.18 Their son Henry McKensie carried the names of his uncle Henry and another member of the Inglis family.19 Their youngest son, Robert Mishaw, was given Mary’s maiden name combined with the name of one of her uncles.20 Henry and Mary Elizabeth named their only child after Henry’s mother, Matilda. Reuben and Harriett Ann’s only child evidently died shortly after birth, before it was named, and Eliza Ann and James M. Johnson had no children of their own.21 In the entire family only one name—John Wilson Buckner—does not conform to the familiar pattern, possibly because his father, Willis Buckner, named him. The name of every other member of the third generation of free Ellisons commemorated the network of love, respect, and authority that knit the family.

WILLIAM ELLISON presided over his sprawling family compound that in 1850 contained sixteen family members spanning three generations. While Ellison’s three sons and his grandson John Buckner worked in his business, they were by no means equal partners. William Ellison never relaxed his grip on the economic empire his family helped build. The sons’ marriages did not fracture the unity of the family, nor did they alter their father’s patriarchal authority. By 1860, when William Ellison was seventy and his sons mature men in or near their forties, the sons shouldered much of the responsibility for the daily operation of the business, but Ellison steadfastly refused to share ownership or control. In 1860, when Ellison’s fortune was at its peak, only Henry owned any land, a measly thirty acres.22 The sons had become slaveowners, but William Jr. owned only one slave, Henry three, and Reuben five.23 They did not own the houses they lived in or the shop where they worked. One day they expected to inherit their father’s wealth, but until then they lived and worked almost entirely under their father’s direction.

The Ellison brothers first became slaveowners during the 1840s, but their slaves were house servants, not income-producing artisans. In 1850 William Jr. owned a sixteen-year-old black woman, and Reuben, a nineteen-year-old black woman. Henry owned a fourteen-year-old girl and a boy, eleven, both black.24 Their father probably gave them the slaves, who most likely did chores around the house and yard, looked after the young Ellison children, and served the children’s mothers. The Charleston brides were no strangers to house servants and may well have expected them as necessary parts of family life, especially in the country. By 1860 William Jr. still owned one slave woman, probably the same woman he had in 1850. Henry’s three slaves included a man, twenty-one, a woman, twenty, and an eight-month-old child. Reuben’s slaves had increased to five, the twenty-eight-year-old black woman Hannah whom he had owned previously, and her four small children five years old and younger.25

William Ellison’s land and slaveholdings multiplied during the 1850s, suggesting that most of the income generated by the family business funneled into his hands. Although Ellison dominated the family economy, he permitted his sons and grandson a small measure of economic independence. From his thirty acres of land, Henry collected the profits from thirteen bales of cotton in 1860.26 William Jr. also made some “cotton money,” evidently from farming a corner of his father’s estate. He also had his own bank account in Charleston. In 1857 he asked Henry, who was in Charleston on business, to withdraw “three hundred dollars that you will see in the W. J. Elison Saving Bank Book with the dividends and surplus dividends that it have drawn,” and leave it at the Ellison’s factors’ office, “subject to Father’s order.”27 His father repeated to Henry that he was to give the factors “the money I have borrowed from William.”28 The three Ellison sons and John Buckner probably took a number of small carpentry and blacksmith jobs on their own account, pocketing the money they earned. Without question Reuben did dozens of small jobs in the 1850s, the largest paying him $45.29 and most of them something between $5 and $20.29 Another scrap of evidence of a measure of financial independence comes from Dr. Anderson’s medical records. Until a few years after the brothers married, Anderson charged their bills to their father. By 1849 each son had a separate account with the doctor, which each presumably paid himself.30

However, these tokens of economic independence illustrate the Ellison brothers’ subordination to their father. He took the lion’s share of the income and reinvested in more land and slaves. He paid them wages, allowed them to grow a little cotton of their own, and permitted them to use the shop tools (and possibly slaves) for some sideline accounts of their own. But they had little opportunity to accumulate their own wealth. On the eve of the Civil War, for example, Reuben—who was forty years old—owned his family of slaves, furniture valued at less than $50, an old shotgun, some books, brushes, and three head of cattle.31 If Reuben and his brothers had relied solely on their own private incomes, their lives would have been nearly as barebones as those of other free people of color.

The one male member of the family who did not work for William Ellison was his son-in-law, the tailor James M. Johnson. Johnson probably did his sewing in his home, “Drayton Hall.” Planters interested in Ellison’s gins were men who appreciated handmade clothing and could afford it. On a visit to the gin shop, they could saunter over to Johnson’s house to be measured for a new outfit. The Moodys, who lived just north of the crossroads, were among Johnson’s regular customers. In 1853 one member of the family bought a plain drill frock coat and pants for $4.50. Two years earlier, he paid $7.00 for a black alpaca frock coat and gray cashmere pants and vest.32 Thanks to Johnson, some Stateburg house servants dressed as smartly as any in Charleston. In January 1851, Richard Singleton had Johnson make a broadcloth jacket, pants, and vest for his butler, William.33 To planters like Singleton, having a tailor from one of Charleston’s best shops just up the road in Stateburg was a delightful convenience. In 1859, when Johnson temporarily returned to Charleston, several Stateburg planters continued to patronize him.34 Another planter “regretted he did not know I was in Town so as he might have got his work done,” and, Johnson reported, the man tried to persuade him to accompany him back to his place in Summerton, a small town in Clarendon District, about twenty miles south of Sumter.35

Like his brothers-in-law, Johnson did not escape dependence on the family patriarch. In addition to tapping Ellison’s list of customers and working out of the family compound, Johnson farmed a few acres of Ellison’s land and grew a bit of cotton. Late in 1859, Johnson wrote Henry from Charleston that he had sold his cotton and thus “will be able to settle up with your Father for Bagging, Rope, &c.”36 A month later he decided to sell his cotton seed too, since he expected to reside in the city for the year and could not plant a crop.37 Johnson also teamed up with William Ellison in the “Ellison & Johnson” shoe business. Most likely, Ellison provided the shop, tools, an occasional slave, and supplies of leather—which he used extensively in his gins—while Johnson supplied the skills and probably much of the labor. Johnson made shoes for the same prominent white families he clothed. In 1854 he made a pair of “fine shoes” for $2.50 for one of the Moodys and four years later a pair of “negro shoes” for $1.12½ for one of the Moodys’ slaves. Johnson also repaired shoes, charging 75 cents for half-soles for “fine shoes,” for example.38 Although he worked as a tailor, cobbler, and farmer, Johnson remained another of William Ellison’s dependents.

THE crowded, bustling Ellison compound should have been ripe for intrafamily tension. Jealousy, envy, and competition for family rank were common in aristocratic white households, especially between brothers and brothers-in-law.39 When Johnson married Eliza Ann and moved into the Ellison compound, he might have become a prime target of hostility from the Ellison brothers. All the evidence points in the opposite direction, however. Johnson seems to have been on friendly terms with all the brothers, and he was especially close to Henry. Letters exchanged between the two when Johnson returned to Charleston in 1859 reveal a warm, affectionate friendship. The long, chatty letters contained gossip and jests as well as candid discussions of marriage, religious faith, and politics. They disclose two men who enjoyed each other’s company. When James ended a letter with “Give my Love to All at Wisdom Hall & accept for yourself the same,” the sentiment was more than perfunctory.40

Johnson’s presence in the Ellison family failed to engender the provocations that tore at other families. To begin with, Eliza Ann did not bring home a stranger. In fact, Johnson may have met Eliza Ann through his friendship with her brothers, documented in their collective baptism at Holy Cross in 1843. Perhaps more important in the long run, Johnson posed no economic threat to the brothers. Had he joined the gin business, the brothers might have had to settle for a smaller share of the proceeds. And, since James and Eliza Ann had no children, the brothers did not confront new heirs challenging their own children for places in the family enterprise and portions of their father’s estate. When Ellison made his will in 1851, he made it clear that Johnson would not obtain a share of his estate. Ellison decreed that his property would follow blood, not marriage. Eliza Ann would inherit her father’s half-interest in “Drayton Hall,” a certain slave, and one quarter of the property that remained after her brothers received certain specific bequests. At her death, her inheritance would pass to her children, and if no child of hers survived, it would return to her brothers, not to her husband.41 Johnson threatened no heir; instead he was a family asset. His crafts generated a cash income, and his acumen in the community buttressed the family’s standing with dominant whites. Johnson made the family compound a busier and more productive place.

Almost no evidence indicates conflict between the Ellison brothers and their father, which at first glance is curious. In aristocratic white families, the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of the patriarch often devastated father-son relationships. The father’s refusal to surrender power created resentment and frustration among those waiting for their turn at the reins.42 Since few white patriarchs were as miserly with property and authority as William Ellison, it would be understandable if the Ellison household had been ripped by generational strife. If the Ellison sons chafed at their father’s dominion, they did so secretly. The evidence indicates a family bound by mutual respect, love, and understanding. Why did the sons submit without taking offense?

William Ellison’s monopoly of productive wealth helped mold obedient, subservient sons. In his 1851 will, Ellison bequeathed to his sons, jointly, “Wisdom Hall,” the gin shop, and shop lot. After Eliza Ann had received her specified portion, each son received an equal share of the remaining property.43 At least by 1851 the sons knew that rebelliousness could lead to disinheritance and the loss of a fortune. Potent as such a threat may appear, similar threats did not always deter the sons of white planters from standing up to their fathers. It is unlikely that Ellison’s control over his property was sufficient to dictate the lifelong deference of his sons.

Unlike planters’ sons who sometimes had nothing to do, the Ellison sons were never idle. From the time they were boys, they turned their hands to every task in their father’s business. As participants rather than observers, they experienced work rather than enforced idleness. They escaped hostility bred by unwanted leisure and thwarted ambition. They received the satisfactions of craftsmanship, and their father allowed them enough work on their own account—in the fields and the shop—to soothe some of the sting of his economic mastery.

The sons of white planters sometimes complained that they could do better if they took over, but the Ellison sons could not fault their father’s performance. Working beside him each day, they could see him handle with equal skill the assembly of a cotton gin, the instruction of a slave, and the shade-tree conversations with white planters about nothing in particular that were crucial to business in the shop and acceptance in the community. An almost flawless leader, Ellison was evidently a humane father. Tough and demanding without apology, Ellison was not like James Henry Hammond, whose haughty arrogance withered his sons’ affections and damaged their lives.44 Ellison appears to have held his sons to standards no higher than those he met each day. As in his relations with the white community, he may have let his deeds do much of his talking. At least, his sons respected him, and instead of becoming passive, self-pitying, ineffectual individuals, they grew into energetic, mature, productive men. It is doubtful that they detected even a tinge of irony in the name “Wisdom Hall.”

Rather than break his sons to his will, William Ellison raised them in his own image. For that reason, they may have thought from time to time about leaving Stateburg and moving far enough away to set up a shop and become their own men. But if they learned nothing else from their father, they learned to calculate the odds against any plan. Anybody other than a reckless adventurer could see that outside Stateburg economic opportunity was constricted and personal safety questionable. To avoid competing with their father, they would have to move outside the High Hills, where they would be unknown free colored artisans competing head to head with white gin makers and blacksmiths. Their chances of duplicating their father’s achievement were slight. When April Ellison came to Stateburg, the cotton boom was in full force, and planters were on the lookout for a good gin maker, even if he was a Negro. A generation later, the cotton boom had moved half a continent to the west, and resentment of free Negro artisans had grown.

The economic balance sheet gave the Ellison sons little reason to take such a risk. Although they did not own much property, they lived comfortably. They did not have to leave the family compound to escape poverty. And while the sons of many planters looked forward to a reduced patrimony as static agricultural estates were subdivided among several heirs, the Ellison brothers anticipated an inheritance that continued to grow vigorously and showed no signs of faltering. Continued subjection to the mastery of their father was entirely consistent with their present and future economic welfare.

If the sons sought greater personal autonomy, abandoning “Wisdom Hall” offered bleak prospects of obtaining it. Free people of color could not hope to establish autonomy in the antebellum South. The freedom of Afro-Americans required white sponsors and protectors. Flight from William Ellison would have cut off the sons from the leading white planters of the High Hills who knew them and valued their work. Successful free men of color shortened rather than stretched the distance between themselves and powerful white friends. Only by assuming a dependent position in a patron-client relationship with whites could free people of color secure their freedom and seek to expand the limits of their circumscribed lives. Stateburg was the locus of the Ellison brothers’ security. Staying there meant remaining their father’s sons. Whatever the stresses of life at “Wisdom Hall,” they were never great enough to drive any of the sons away from home.

William Ellison was obsessed with preserving the freedom of his entire family, and his sons seemed to identify their welfare as individuals with that of the family as a whole. They seemed to share their father’s belief that the best way to confront the family’s vulnerability was solidarity. Unity meant a communal economic life and acceptance of William Ellison’s leadership. The corrosive reality of white society lay just beyond William Ellison’s front yard, and his sons knew it. The Ellison brothers understood the place of free Negroes in Southern society. That understanding shaped their response to their father’s rule. They chose to follow him and hoped eventually to succeed him.

LIFE in the Ellison household was almost too good to be true. Even the three young Charleston women evidently made a satisfactory adjustment to Stateburg. When John L. Manning married Sallie Clarke of Virginia in 1848 and brought her back to his family’s palatial “Millford,” just a few miles south of Stateburg, Sallie described the experience as an “ordeal,” the “severest to which a young girl can be subjected.” She received “the very greatest kindness & affection as a member of the family,” and she said “every effort has been made to make me feel as one of them.” Family members called her “daughter,” “Sister,” “Cousin,” and “Aunt,” but she still felt isolated in “a land of strangers.”45 For the young Ellison wives—accustomed to strolls along the Charleston waterfront, shopping in stores on King Street, and visiting in the parlors of dozens of free colored homes—the family compound in Stateburg made a small world. The upcountry was a trial for young white women from Charleston who fled there during the Civil War. One who settled near Camden grumbled about the lack of amenities and society. Few “seek us socially to walk or ride in the afternoons or come over to see us after tea,” she fussed. “If we go out to walk, we find a disagreeable sandy uneven road and scarcely ever meet an acquaintance to enliven the way….” She found the neighborhood all “dullness & monotony.”46 The Ellisons’ Charleston brides had even fewer resources in the surrounding community, but their growing families and the activities in the Ellison compound evidently kept them occupied, for they stayed.

Moving to Stateburg did not require the young women to sever their connections to family and friends in Charleston. The lives of the upcountry Ellisons intertwined with the Charleston Bonneaus, Mishaws, Johnsons, and their assorted friends and kinfolk. The hundred-mile trip to Charleston was a hard, dusty journey before the railroad pushed into the interior. By the 1840s, the South Carolina Railroad snaked along the eastern edge of the Wateree Swamp just below “Wisdom Hall.” Trains to and from Charleston stopped at the Claremont Depot, less than a three-mile buggy ride from the Stateburg crossroads. Ellison slaves carried family members to the station and fetched them when they returned.47 Just enough evidence survives to suggest that a trip to Charleston was a special occasion but one that the Ellisons indulged in freely, both for pleasure and business. In December 1859 Henry and Mary Elizabeth’s daughter Matilda went down to spend time with her grandmother, Mrs. Jeanette Bonneau.48 In previous years Mrs. Bonneau had come to Stateburg for a long visit, and a sister of Henry’s and Reuben’s wives announced her intention to “pay Stateburg a visit” and bring along her daughter Jany.49 Family traffic clearly went both ways.

Economic ties also stretched between Stateburg and Charleston. In 1848 John F. Weston, a free mulatto machinist who married another of Thomas S. Bonneau’s daughters, consulted with Henry and Reuben about the impending sale of their father-in-law’s estate. Six town lots, the buildings on them, and four slaves were scheduled for the auction block. Weston proposed that the heirs adopt some plan “to get the value or nearly” for the Bonneau property, which was being sold because of a lawsuit against the estate by Bonneau’s son, Thomas Collins Bonneau.50 Weston suggested that the family “procure a Bidder to run the property to what we consider to be a fair price.” He wanted Henry and Reuben to agree to the plan before he proceeded, since the scheme could backfire if the property were “knocked down to us.”51

The Ellisons also were in a position to lend a hand to needy relatives on occasion. In 1855 Jacob Weston, a free mulatto tailor who had married yet another Bonneau daughter, wrote Henry thanking him for the money he had sent for Mrs. Jeanette Bonneau. It had arrived, he said, “just in time.”52 In time for what is unknown. After her husband’s death and the disposal of his estate, Mrs. Bonneau lived in a modest house on Coming Street, paying taxes in 1860 on one slave and real estate worth $1,000.53 The aid she received from one of her Ellison sons-in-law, via another son-in-law who could give it to her personally and smooth her acceptance of it, is a tangible illustration of the emotions that laced Ellison kin.

The Ellisons traveled to Charleston often to deal with cotton factors, supply merchants, and bankers. For example, in 1857 Henry went to the city with instructions from his father to deposit money with E. L. Adams and E. H. Frost, white commission merchants and factors on Adger’s north wharf who had handled Ellison cotton for years. William Ellison also asked Henry to stop by Joseph Ellison Adger’s hardware store on East Bay and buy a half-dozen weeding hoes, two hand saws, and eight bags of guano.54 Adger’s middle name came from his mother, Sarah Elizabeth Ellison, the sister of white William Ellison, the Fairfield District planter who owned April until 1816.55 The marriage bonds within the white family may have had something to do with William Ellison of Stateburg taking his trade to Adger’s hardware store. While he was in the city, Henry had several other errands to do for his brother William. He had orders to withdraw money from William Jr.’s bank account and give it to Adams and Frost, to arrange to have a pair of trousers made for John Buckner, to buy a handkerchief and some boots for slaves, and to pick up a pound of starch and four pounds of bird shot.56

Family members were not the only ones who sent him traipsing from one shop to another in the city. When Henry was in town in 1858 he received a letter from a family friend among the Sumter Turks, passing on a request from Louisa Murrell, General Thomas Sumter’s elderly granddaughter who lived near the Ellisons in Stateburg.57 She “asks you to bring a paper of green glazed cabbage & one or two of Leek seed & she prefers them from Landreths seed store,” Henry was told by his friend. He added, “She will give me the money to hand you.”58 Whether Landreth’s seed store had previously been on Henry’s list of stops, he doubtless added it, even if it was a bother. The willing performance of small favors, especially those attentive to preferences, cemented personal relations with important white people and constituted a social obligation as well as a familial duty.

Trips to Charleston were not all business, however. We know virtually nothing about what the Ellisons did for fun, but they certainly took pleasure in visiting kinfolk and friends every time they came to the city. They evidently attended church with the Johnsons, and probably enjoyed renewing friendships with the city’s many free colored tradesmen, who brought the Ellisons up to date on the latest news from their distinctive perspective. And the Ellisons never neglected to stop and see Mrs. Bonneau. After the early 1850s, however, those visit must have been tempered by sadness.

BREEZES and a moderate climate gave the High Hills a reputation for health, but beginning in 1850 the Ellison family compound was touched repeatedly by death. On January 14, 1850, Matilda Ellison died. Fifty-six years old, the matriarch of the Ellison clan became seriously ill in October 1849. She received scores of visits from Dr. Anderson before she finally succumbed.59 Her husband made the arrangements for a funeral at Holy Cross and laid her to rest beneath towering oaks that grew a hundred yards north of “Wisdom Hall” at the bottom of a gentle slope. Matilda’s grave was the first in what became the family graveyard.

Two years later, on September 15, 1852, Henry’s twenty-eight-year-old wife died, after a debilitating illness. On her granite tombstone Henry had the stone cutter inscribe:

Thy Race though Short is done Mary

And thou art gone to rest

In Heaven that Bright and blissful land

Upon they Savior’s breast

No More shall torturing pain, Mary

Disturb or rack thy frame

No more shall tears of sorrow fall

Upon thy cheek Again

Rest Mary Rest for Christ Himself

Was Once the Dark Grave’s Quest

This Heavenly One the Prison changed

Into a place of Rest.60

Less than eight months later, Mary Elizabeth was followed by Mary Thomson, William Jr.’s twenty-four-year-old wife. The inscription cut on her tombstone reads, in part:

In the Prime of life and the

Vigor of Youth, she was Visited with

A painful and lingering disease

And as a Christian, she bore

With patience through faith

In her Redeemer, Until her

Spirit was called away unto

Him that gave it.61

The ordeal continued. Seven weeks after the death of his wife, William Jr. lost his infant son Henry McKensie.62 In December 1853 Reuben’s wife Harriett Ann died, evidently from complications of childbirth.63 The next May, William Jr.’s three-year-old son Robert Mishaw passed away.64 In less than four years the family suffered six deaths, five of them in only twenty months. Some may have been victims of a terrible epidemic that ravaged the South Carolina upcountry between 1852 and 1854. The pestilence was so deadly that in September 1853 the governor of the state set a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer to seek deliverance from the scourge.65

All six of the Ellisons received church burials. The services were held in Holy Cross’s beautiful new building, constructed in Gothic design from the unusual material of Stateburg earth tamped into thick, buff-colored walls. Light filtered into the cool, dark sanctuary through imported stained glass windows.66 Harriett Ann’s body was evidently returned to Charleston for interment. But after each of the other services, the Ellisons and their friends accompanied the deceased family member back across the road and down the hill to the family burying ground, where the coffin was lowered into the grave.

After 1853, Eliza Ann was the only free woman left in the family compound. To her duties as mother of John Buckner and wife of James M. Johnson were added all the obligations of her deceased mother and three sisters-in-law. She became the mistress of the household, supervising the household slaves, taking care of her bereaved brothers and father, and stepping in as surrogate mother for her young nieces and nephews. All the children may have moved into her house. At least they stayed with her when they were sick. In Henry’s account with Dr. Anderson, an entry for September 27, 1852, notes, “Visit for daughter at Johnsons.”67 William Jr.’s account includes an entry for May 9, 1854, reading, “Two visits for your child at Johnsons.”68 In 1857 a new free woman of color from Charleston joined the family circle. John Buckner married Jane Johnson, who was evidently the sister of his stepfather, James M. Johnson.69 The Buckners lived in “Drayton Hall” with the Johnsons, but in 1860 both Jane Buckner and her infant son died, leaving the couple’s two-year-old daughter Harriet Ann for the care of Eliza Ann.70 Again, Eliza Ann was the solitary mistress of both “Drayton Hall” and “Wisdom Hall.”

Eight deaths in one decade threatened the Ellison family with disintegration. But it did not disintegrate. Despite all the heartache of the 1850s, the family compound remained a refuge and a source of strength. An iron-willed patriarch could not stop death, but he could defy it. Under William Ellison’s direction, three generations continued to live and work together. Although William Ellison was in his seventh decade, he refused to relinquish mastery.

IN 1860 leading citizens of Stateburg considered William Ellison a gin maker. Ellison advertised that identity in local newspapers, and in both 1850 and 1860 censuses he reported that as his occupation. The report was accurate as far as it went, but it bespoke a studied modesty. Over the years, Ellison had expanded his economic activity far beyond the gin shop. Judged by the size of his slave force, his acreage, and his annual cotton crop, Ellison had become a large cotton planter as early as the 1840s. There is no reason to doubt Ellison’s pride in his status as a planter. But he did not parade it. Had he stopped working as a sweat-stained mechanic, had he sold off the gin shop and become a full-time planter, he would have suggested to the white community that he had forgotten his place, that he was pushing for equality. Whites may have decided that he needed to be taught he was not white. As a gin maker he provided a service to the white planters and stayed visibly tied to his origins and his place. Ellison’s white neighbors knew he had a cotton plantation and many slaves, but his gin shop depended on their business, served their needs, and convinced them that old William Ellison was their kind of colored man.

At first glance, the 1840s were far less bountiful for Ellison than the 1830s. After striding forward in seven-league boots in the thirties, he slowed the pace of his acquisitions of slaves and land. In 1850 as in 1840, the gin shop employed twelve adult men, presumably Ellison himself, his three sons, his grandson John Buckner, one or two free men of color, and five or six slaves, plus an uncounted swarm of slave boys.71 Clearly, the gin business was not infinitely expandable. Ellison’s territory in the High Hills could absorb just so many gins. The radius of his blacksmith and carpentry business was shorter still, attracting many small jobs from planters within easy travel distance and occasionally a major project from a planter who did not trust it to his slave artisans.

Records that would permit an estimation of the profitability of Ellison’s shop have not survived. The only evidence comes from Ellison’s report in the 1850 census, and it is misleading. Ellison told the census enumerator that his income from the gin shop was $3,000 a year and that his expenses included $240 a month for labor and $580 a year for raw materials.72 According to these figures, Ellison’s annual expenses exceeded his income by $460. Ellison’s estimates of his costs are probably fairly accurate, but the implication that he lost money is false without question. Ellison said he paid $280 for 2,000 pounds of iron and steel, which he probably purchased in Charleston. He estimated his lumber costs at $200. He cut a good deal of lumber from his own land, but he also bought additional lumber locally. In 1860, for example, he paid Dr. W. W. Anderson $117.08 for lumber from his sawmill on Rafting Creek.73 Ellison estimated his expenses for “other articles,” which would have included such things as leather belting and pig bristles, at $100. Ellison bought pig bristles, a lowly but crucial component of gin brushes, from local planters, who realized a little pocket money, or perhaps credit with Ellison, for this otherwise useless commodity.

Ellison’s largest expense by far was for labor, which amounted to $2,880 for the year. He did not pay his slaves a wage, and their subsistence costs were almost negligible because by 1850 he produced most of their food on his plantation. The wages Ellison paid were divided among the five or six free men of color who worked in his shop in 1850, all but one or two of whom were Ellisons. Assuming a wage of $40 a month, a reasonable rate for a gin maker, Ellison’s $240 monthly outlay for labor went into his pocket and that of his three sons, possibly his grandson, and maybe one or two other free Negro tradesmen. Depending upon whether a full month’s wages went to him and his grandson, he paid somewhere between $120 and $200 of his monthly wages to family members. Since all the Ellisons lived together in the family compound, the elder Ellison had access to his sons’ labor around the clock to aid him on his other income-producing activities, principally his plantation. By marking off to the gin business all the wages he paid his sons, he exaggerated his gin shop labor expenses to the extent that his sons helped him make money in other ways. For example, although Ellison had a large number of slaves, there is no evidence he ever employed an overseer. Presumably he and his sons shared that responsibility, saving him a sizable expense. No doubt such considerations did not enter the estimate he gave the census marshal. Yet it was precisely such considerations that made his family enterprise profitable. Furthermore, by paying his sons wages he presumably was allowing them to buy for themselves what he would have otherwise paid for and had in fact paid for until they established their own families in the middle 1840s.

By the 1850s and probably well before, Ellison’s plantation eclipsed the gin shop as a source of income. The shop kept busy and continued to turn a profit. But perhaps most valuable of all, it moored Ellison to his beginnings as a tradesman. Paradoxically, Ellison’s gin shop bound him to his slave origins and set him apart from white planters while its profits drew him into the planter class. Ellison’s prudent behavior throughout his life suggests that he understood mat his money could buy him a great deal, including trouble.

In 1847 Ellison boosted his land to a little over 350 acres. He paid the Sumter family $270 for a tract of 22 and one-half acres that lay just north of the gin shop.74 During the 1840s his slave force grew to thirty-six, six more than in 1840. His slaves were still predominantly males (twenty-six of thirty-six), and sixteen of them were over ten years of age. Ellison’s decision to buy females in the 1830s continued to pay off in slave children. In 1850 he owned eleven slaves under the age of ten. Although much of the change that occurred within his slave population may be hidden by the census reports, we can say with certainty that during the decade he acquired five new females in their twenties and lost four older women and one girl who was under ten when the decade began. Ellison’s male slaves increased by five, but most were boys, and he lost at least two older men and one in his middle years.75 The only extant record of Ellison adding to his slave force comes from February 1845, when he bought January for $545 at an auction of the personal property of Thomas Sumter, Jr. Thirty-three slaves changed hands that day, and, like the other buyers, Ellison put down a little cash—$41.85—and gave his bond for the rest.76

Despite only modest gains in land and slaves, Ellison experienced no economic difficulty in the 1840s. The marriage of his sons followed shortly by new grandchildren increased his expenses. However, the most important reason for the modest growth of his empire was his decision to divert income from the acquisition of property and slaves to the accumulation of capital. Ellison fattened his savings during the forties, preparing for his spectacular expansion during the 1850s.

By 1860 Ellison had increased his slave population by a stunning 75 percent, from thirty-six in 1850 to sixty-three in 1860. His twenty slaves under ten years of age indicate that he continued to profit from natural increase, but he was also active in the market. At a minimum, he purchased during the decade three females between the ages of ten and twenty-nine and seven males in their twenties.77

Except for his acquisition of January at Sumter’s auction in 1845, we do not know where Ellison acquired the slaves he purchased. As he did when he bought January, he may have ridden a few miles to some High Hills plantation where there was a sale, prompted by migration to the west, economic hard times, or the division of an estate following the death of the owner. When Colonel Richard Singleton died in the 1850s, for example, his creditors descended, forcing the sale of slaves from his huge slave community.78 When Thomas S. Bonneau’s estate was auctioned off in Charleston in 1848, Ellison evidently purchased one of Bonneau’s slaves, a young boy named Isaac.79 But Ellison did not need to travel all the way to Charleston to buy slaves. Slave sales occurred regularly in the neighboring towns of Columbia, Camden, and Sumterville. On December 22, 1853, Isaac Lenoir of Stateburg publicly announced that he would be at the Sumterville courthouse the following Monday to sell fifty slaves, nine mules, and a mare.80 Local planters also sold individual slaves whom they found redundant, or wanted married to a spouse on a neighboring place, or with whom they were displeased. Perhaps most often they sold slaves simply because they needed cash. Ellison could have arranged a private sale, as William Benbow did in March 1857, when he bought Jack for $1,112 from a Stateburg slaveholder.81 Although we cannot establish the manner or place of Ellison’s purchases, he had plenty of opportunities to strike a deal without venturing far from home.

As he had during the 1830s, Ellison matched his slave purchases with land. In 1852 the Sumter family sold him “Keith Hill” and “Hickory Hill,” together more than 540 acres. In a single transaction, the largest of his life, Ellison more than doubled his real estate. The land stretched out to the north and west of Ellison’s other property at the Stateburg crossroads. His mortgage stipulated a price of $9,560, to be paid in five annual payments. Ellison, however, paid off the entire amount after only one year.82

In 1860, for the fifth and final time, a federal census marshal visited William Ellison. Ellison told the marshal that his personal estate, comprised mainly of his slaves, had a value of $53,000, and that his real estate, which he said consisted of 800 acres, was worth $8,25o.83 In fact, Ellison understated his worth. Even if his personal wealth had been made up exclusively of his slaves, which it was not, his estimate of the average value of his slaves was $840. That was about right for a typical plantation where almost all adult slaves were field hands. But Ellison’s operation was not typical. Many of his twenty adult slave men were highly skilled craftsmen, and their value in the market could easily have been two or three times higher than average. Ellison also underrepresented the size and worth of his real estate. Instead of the 800 acres he declared, he owned nearly 900 acres. And his estimation of its value—$8,250—was less than half the amount he paid for it.84 High Hills real estate no longer appreciated rapidly, but neither did it depreciate.

Even judged by the questionable census figures, Ellison’s economic achievement was impressive. Compared to his free Negro neighbors in Sumter District, Ellison possessed princely wealth. Almost half (45 percent) of the free persons of color in Sumter were propertyless. The mean wealth of all free Afro-Americans in Sumter, excluding the Ellisons, was $205. The sum of the real estate owned by all the free persons of color in Sumter did not equal Ellison’s. His personal property exceeded the total personal estate of all 328 other free Negroes in the district by a factor of seven. Ellison’s real estate was worth 80 times more than the mean of free persons of color in Sumter; his personal estate was more than 500 times greater.85 Ellison’s wealth topped the total wealth of all the free persons of color in twenty-five of the state’s thirty districts.86

Ellison had also outdistanced 90 percent of his white neighbors in Sumter. In 1860 the mean wealth of the free families in Sumter was $21,100, higher than in any other district in the state.87 Twenty-six white planters owned 1,000 or more acres, and twenty-one held 100 or more slaves.88 Dr. Anderson, for example, owned real estate worth $30,000 and personal property valued at $100,000, including 149 slaves.89 George Cooper, another white planter in Sumter, possessed real estate worth $70,000, $350,000 in personal property, and 374 slaves.90 Although Ellison’s wealth did not rival the white aristocracy’s, he was among the top 10 percent of all Sumter slaveholders and landowners. In the entire state, only 5 percent of the population owned as much real estate as Ellison. Only 3 percent of the state’s slaveholders owned as many slaves. Compared to the mean wealth of white men in the entire South, Ellison’s was fifteen times greater.91 Ninety-nine percent of the South’s slaveholders owned fewer slaves than he did.92

However, Ellison was neither the richest free person of color in the South nor the largest slaveholder. Louisiana contained six free Negro planters who were wealthier and owned more slaves.93 The richest was Auguste Dubuclet, a sugar planter whose estate was valued at $264,000. The largest slaveholders were the widow C. Richard and her son P. C. Richard, also sugar planters, who together owned 152 slaves. Outside Louisiana, only one free Negro in 1860 is known to have reported greater wealth than Ellison. London Berry, a thirty-eight-year-old mulatto steward in St. Louis, owned real estate worth $67,000, a sum larger than the wealth Ellison reported in the census but not above the actual value of his property.94 No free person of color outside Louisiana is known to have owned more slaves than Ellison in 1860. Since the Louisiana planters tended to be second- and third-generation free people, it is likely that Ellison was the richest Afro-American in the South who began life as a slave.

OVER the decades, Ellison spent an enormous sum to acquire his real and personal property. Calculating the cost of his real estate is straightforward. Between 1822 and 1852, the dates of his first and last purchases, he paid $16,900 for land.95 Figuring his outlay for slaves is more speculative. From his first acquisition sometime before 1820 to his final purchase in the 1850s, Ellison bought an absolute minimum of thirty-five slaves, and he may have bought twice that number.96 If their average purchase price was $500, a conservative estimate considering that he usually bought young adult men and women, then he spent at least $17,500 and as much as $35,000 or possibly more for slaves.

Estimating the cost of Ellison’s investments is easier than figuring his income. Existing evidence permits only the roughest estimate, and then only toward the end of his career. By far the most important source of revenue over the years was Ellison’s shop, which he claimed in 1850 produced an annual income of about $3,000 before the costs of labor and raw materials were subtracted.97 Agriculture provided Ellison’s second major source of income. He produced cotton, his only important cash crop, beginning in the 1830s, but his largest crops came in the 1850s, after he had more than doubled his acreage and nearly doubled his slave force. In 1860 Ellison stated that his fields yielded eighty 400-pound bales of cotton, which at ten cents a pound had a value of about $3,2oo.98 After Adams and Frost, his factors in Charleston, had deducted the charges for transportation, storage, insurance, and their fees, Ellison would have ended up with somewhat less.99 His 500 acres of improved land also produced 2,000 bushels of corn, 1,000 bushels of sweet potatoes, 200 bushels of peas and beans, and forage for forty hogs, twenty-one sheep, and ten cattle, all of which made his plantation self-sufficient in provisions.100 Hiring out slaves and a few other minor enterprises also brought Ellison some income, but only in trivial amounts.

How did Ellison save enough of the income from his shop and fields to pay for the property he bought? The records of his purchases do not even hint that he received special favors, under-the-table gifts, or reduced prices. If anything, he paid a premium. No white benefactor lined Ellison’s pockets. That Ellison paid his own way is certain, but how is not. He invested something between $35,000 and $50,000 during his lifetime, and his peak annual income, that of 1860, was roughly $6,200 before expenses. His expenses were substantial, they underwent important changes during his career, and they are impossible to estimate with any confidence. Just maintaining his large extended family was a major expense. In addition he had to pay for the maintenance of his slaves, stock his plantation and shop with tools and supplies, cover court and legal fees, and foot the bill for expensive medical care, property taxes, factors’ charges, transportation, special taxes on free Negroes, pew rental at Holy Cross, and a hundred and one other items. Nevertheless, after making all these payments Ellison had enough left over to stash away money for more land and slaves. His income was not large enough to have made saving that much money easy, especially in the first two or three decades. Besides working hard and working his slaves hard, Ellison followed two other practices that seem to have been particularly important in allowing him to amass his capital.

The first simply was that, after paying the expenses of production, Ellison did not spend very much. He scrimped, saved, and squirreled away every dime he could. His standards of consumption were in fact limited by his race. Unlike white planters, he did not try to cut a fine figure, build and furnish a mansion, or underwrite tours of the continent. “Wisdom Hall” was not ostentatious. Ellison’s household furniture was serviceable but hardly grand; it was worth $230 altogether, little more than a white planter might pay for a piano. Although the Ellisons had house servants, they did not maintain a retinue of the dozen or more common in white households in Stateburg. Ellison owned both a carriage and a gig that carried him and his family to church and the train depot, but their combined value of $20 does not suggest ornate conveyances. The Ellison brothers took an interest in horse racing—the obsession of several High Hills grandees—but the family owned only horses that never set foot on a racetrack. Ellison’s best horse, a sorrel mare, was worth $150, the same value as Burtrand, one of his mules. The only display Ellison permitted himself was a gold watch and chain, valued at $100.101

A racial ceiling also hung over the aspirations of his children. His sons did not need expensive medical or legal educations, since their race closed those professions to them. His daughter did not need a closetful of fancy gowns and an attractive dowry to find a husband. Ellison had no need to copy the expensive hospitality of the white planters, barbequeing a side of beef and tapping a barrel of whiskey for his lesser neighbors while he enjoyed a glass of Madiera with his peers. Expenses that white planters considered necessities were luxuries for Ellison, even dangerous luxuries. Ellison saved more than all other free people of color because he had a larger income, and he spent far less of it than whites who had larger incomes and appetites. When Ellison spent money he seems to have kept his eye constantly on buying production, on capital expenditures that ultimately would increase, not reduce, the bottom line.

Ellison probably had another source of income, however, one revealed only in the composition of his slave population. Every census indicates that Ellison’s slave population had an unusual structure. In each decade his male slaves heavily outnumbered his females. In 1820 and 1830 he owned only adult men. In 1840 the ratio of adult men to adult women (including the age category of ten to twenty-four as “adult”) was 16 to 6, almost 3 to 1. In 1850 the adult sex ratio (using twenty years and over as “adult”) was 14 to 7, or 2 to 1. In 1860 Ellison owned twenty-three adult males and sixteen adult females, a ratio of nearly 3 to 2. The sexual imbalance among Ellison’s adult slaves also appeared in more extreme form among his slave children. In 1840 he owned eight children, five of them boys. In 1850 nine of his ten slave children were boys. In 1860 boys comprised fifteen of his twenty slave youngsters. In Ellison’s quarters, female slaves were few and young females were rare. In 1850, after owning several slave women in their child-bearing years for more than a decade, Ellison had only one female slave under the age of 18.102

Assuming that nature presented approximately equal numbers of little girls and little boys to slave mothers belonging to Ellison, there is a shortage of about twenty young girls in Ellison’s census rosters. The best explanation of that shortage is that Ellison sold slave girls. The evidence is not conclusive, since, as with his slave purchases, records of his slave sales do not exist. Certainly Ellison did not object to selling slaves. In his will he directed his executors to sell a young woman named Sarah and to divide the proceeds among his heirs.103 Grim as it is, selling is the most plausible way to explain the missing slave girls. No evidence exists of a mysterious sex- and age-specific disease sweeping decade after decade through Ellison’s quarters.

Nor is there any evidence that Ellison created the imbalance by purchasing additional boys. If the boys who appear in the census were bought, Ellison’s slave women were nearly barren. The census figures already suggest very low birth rates. If Ellison’s slave women had produced equal numbers of girls and boys (that is, an additional twenty children), their fertility rates would still be lower than we might expect on a plantation with a high ratio of men.104 Assuming that the mothers of the twenty slave youngsters who appear in the 1860 census were the eight women between the ages of eighteen and twenty-nine in the 1850 census plus the three additional women of childbearing years Ellison acquired during the 1850s, they would have had to produce fewer than three children each during the decade to account for the fifteen boys and five girls in the census and the ten absent little girls. Moreover, the census of 1860 lists children with their mothers, at least with women whose ages allow us to believe that they were the mothers of the children who follow them on the slave schedules. For example, a thirty-two-year-old female is followed by males aged thirteen, ten, eight, six, and four months. A forty-year-old slave woman is followed by males aged twenty-one, thirteen, seven, and four.105 These age patterns would be unlikely if Ellison bought slave boys of random ages in the market. The listings even leave spaces for the births of missing girls.

The whereabouts of the girls could be easily explained if Ellison had given them to his children. But Eliza Ann never possessed any slaves of her own, and while Ellison’s three sons were slaveholders by 1860, each owned only one female whose age could possibly have allowed her to come from the group of missing children.106 The final alternative explanation is that Ellison was a closet abolitionist who secretly freed his young females. This possibility is farfetched. There is no evidence whatever that Ellison ever freed one of his slaves, either while he lived or by his will after his death. He dedicated his life to accumulating property, not dispersing it. To Ellison, slaves were property, without question. Besides, being a Negro emancipator would hardly have added luster to his reputation in Stateburg. To free slaves, which was illegal in any case after 1820, would have destroyed a lifetime’s effort to prove himself a reliable, solid citizen.

Why would Ellison sell off black girls? The best answer is that he sold them to help raise the large sums he needed to buy more adult slaves and more land. By turning human capital into cash, he was able to sustain an aggressive program of expansion. To him, slaves were a source of labor, and the laborers he needed most were adult men who could work in his gin shop. Men, as a rule, were also stronger workers in the fields. Even though slave women often had less strength and endurance, they did valuable work for Ellison in his fields, but it was not as valuable as having babies.107 Their boys could grow up to be workers in Ellison’s shop or full hands in his fields, but in Ellison’s eyes their girls could never provide the labor he most wanted.

Rather than accumulate slaves he could not exploit to the fullest, he probably sold twenty or more girls, retaining only a few who could eventually have more children, cultivate his fields, and in a few cases work in his home as domestics. To Ellison, slave children were either future labor or ready cash, depending on their sex. If Ellison sold twenty slave girls for an average price of $400, he obtained an additional $8,000 cash, a sum large enough to have made a major contribution to the land and slave purchases that made him a planter. Evidently, Ellison’s economic empire was in large part constructed by slave labor and paid for by the sale of slave girls.

SURELY, it might seem, selling little girls would have stigmatized William Ellison in the eyes of influential whites in Stateburg. Certain standards for the treatment of slaves had taken root in the South in the decades before the Civil War.108 The code of paternalism—at minimum the exchange of decent care in return for obedience and hard work—was honored in the breach more often than not, but there were planters in Sumter District who felt constrained to try to abide by its tenets. The code did not normally countenance selling children away from their immediate families. A former slave of John Frierson, master of “Pudden Swamp” a few miles east of Sumterville, remembered that his former owner was never “known to separate mother and children.” Frierson simply “did not believe in this kind of business.”109 J. K. Douglas of Camden did not believe in that kind of business either. In February 1848 he wrote John B. Miller of Sumterville to explain the plight of “that valuable Christian man of colour, Charles,” who was about to be sold and separated from his wife and children because of the death of his master. Separation would make Charles “miserable,” Douglas explained, and he asked if Miller could not possibly buy the slave and preserve the family.110 Sumter District planters did their share of buying and selling, but most resisted breaking up families, at least as a conscious policy. Someone who was entirely dependent on the good opinion of the white community could not afford to be blind to prevailing practices.

White planters may have reserved their paternalistic expectations for each other and exempted a free man of color like Ellison from their strictures. More likely, however, the planters’ paternalism was a very forgiving standard. What protected Ellison from public censure was his economic situation, not his race. Owners who sold slaves had to have a reasonable excuse, and Ellison had one. Unlike white planters who prized the laboring capacity of slave girls only slightly less than that of boys, Ellison had no use for girls in his shop and only a limited use in his fields. For him girls were a financial burden. Paternalism was never so rigid a code as to cause any slaveholder economic distress. Even staunch defenders of the duties of planters believed that slave sales, however regrettable, were sometimes unavoidable. Perhaps the fact that no town gossip latched on to Ellison’s sales is indirect evidence that Stateburg residents understood and accepted Ellison’s very different labor requirements. Some, like John Frierson of “Pudden Swamp,” may have disapproved, but there is no evidence that anyone ever branded Ellison a heartless monster for separating girls from their mothers and selling them. They considered Ellison a respectable man, a reputation he had worked hard to earn and one he would not have risked for the world, certainly not for a few more acres of it. Far from condemning practices like Ellison’s as barbaric, white planters condoned them.

Local tradition is silent about Ellison’s slave sales but outspoken about his reputation as a harsh master.111 His slaves were said to be the district’s worst fed and worst clothed. The story jibes with certain of Ellison’s character traits and with his circumstances. Year after year Ellison drove himself relentlessly. In January 1841, for example, Natalie Delage Sumter, widow of Thomas Sumter, Jr., recorded in her diary that the previous night she had gone to bed at eleven o’clock, only to be awakened by her house servants, who told her that William Ellison “had come to settle his accts.”112 A fifty-one-year-old tradesman who was still out collecting at midnight in the dead of winter probably had few qualms about stretching his slaves’ workday from before sunup to after sundown. Hungry for more land and slaves, Ellison and his family lived frugally, and he probably was even more tightfisted in providing food, clothing, and housing for his slaves. If he did treat his slaves harshly, it may have been because he dealt with an unusually hostile slave community, bitter men and women who had seen their daughters sold away. Harsh treatment could also have stemmed from Ellison’s need to prove to whites that, despite his history and color, he was not soft on slaves. A reputation for harshness was less dangerous than a reputation for indulgence.

Although the rumor that Ellison was a cruel master is plausible, there is no evidence to confirm it. Aside from his apparent practice of selling girls, Ellison probably acted about like any other High Hills slaveholder, no better, no worse. Sensitive to public opinion, he probably did not stray too far from prevailing practices. Stern discipline and stingy maintenance hardly distinguished his mastery from whites’. Most slaves endured such treatment regardless of the race of their masters.113 The origin of Ellison’s reputation as a tough skinflint of a master may rest partly in the white community’s familiarity with Ellison’s slaves, who worked in tattered garments in the fields or shop near the crossroads, visible to all who passed. His slaves were not isolated on plantations miles away down along the Wateree swamp or scattered through the hills.114 The way Ellison treated his slaves was on public display every day, and white observers took notice. What they saw is impossible to tell; what they noticed says as much about them as about Ellison. It is also possible that the story of Ellison’s harshness was no more than a self-serving tale begun by whites eager to defend their own stewardship of slaves by contrasting it with the cruelty of a black master, the meanest slaveholder in the district.

In reality, little is known about Ellison’s slaves or his relationship with them. The census, however, reveals that all of Ellison’s slaves were black. None was ever listed as a mulatto.115 Normally a slave population the size of Ellison’s would have included a sprinkling of light-skinned Negroes. Mulattoes made up 5 percent of South Carolina’s slaves in 1860.116 If Ellison’s slaves had reflected that proportion, three of them would have been mulattoes. His all-black quarters may have been the result of a conscious decision. A mulatto owning other mulattoes as slaves may have been too much of a contradiction for Ellison. Or his dependence on the good opinion of whites may have convinced him that he could not risk having tongues wag about the paternity of mulattoes on his plantation the way they did about the mulattoes who belonged to white masters. By color coding his plantation, Ellison created a safe distance between his family and his slaves. On his plantation, like almost all others, both status and color differentiated the master from his slaves.

Ellison’s slaves sometimes ran away, as did slaves on neighboring plantations. The historian of Sumter District reported that from time to time Ellison advertised for the return of his runaways.117 On at least one occasion he hired the services of a slave catcher. According to Robert W. Andrews, a white man who purchased a small hotel in Stateburg in the 1820s, “a valuable slave, who was a fine mechanic, a cotton-gin maker, belonging to Mr. William Ellison, made a break for the Free States.” Andrews remembered that “Mr. Ellison offered me five dollars a day [and] to find me a horse and pay my expenses, if I would bring back the slave, whom he estimated at two thousand dollars value.” Andrews first inquired in Manchester, a small town about ten miles south of Stateburg, where he heard that the runaway had joined a group of jockeys headed for Virginia. Following the trail, Andrews caught up with the slave in Belleville, Virginia. “I was paid on returning home,” Andrews said, “$77.50, and $74.00 for expenses.”118 In the same decade, another High Hills slaveholder—Richard Singleton—was willing to track a runaway even farther. In April 1822 James Usher informed Singleton that “your boy William” had been captured in New York City and that the slave was in jail in Wilmington, North Carolina, awaiting shipment home. Usher added that “your boy Davis” had also been spotted in New York, where he was married to a free woman, and that he expected Davis would soon be collared.119

While most of Ellison’s slaves never ran away, some were out on the road on business. A few skilled men probably traveled to local plantations to make repairs, just as Ellison himself had while he was a slave in Fairfield District. Many of Ellison’s men would have had to be abroad if they were married. The sexual imbalance among his slaves made it impossible for them to find a wife at home. If they married off the plantation, Ellison would have to give his permission and provide them special passes for occasional visits to their spouses. The practice of marrying off the plantation was common in the High Hills. Remembering Stateburg in the 1830s, Samuel McGill said, “In those old times one might travel a whole day without meeting anyone, because there was not many people except on plantations, and they had Little or no business out of it; colored husbands excepted, having wives on neighbors’ places.”120

Grueling as their lives were, the slave men who worked in Ellison’s gin business may actually have had certain advantages. Their work as mechanics was exhausting, but they probably preferred it to monotonous, back-breaking days in the fields. As one Camden planter observed in 1831, “Negroes are fond of acquiring trades as it gives them an opportunity of making something for themselves.”121 Masters sometimes allowed their skilled artisans to work a little on their own after hours and to keep their earnings. One bit of evidence suggests that Ellison permitted at least one of his slaves such a privilege. The ledger of the tavern that stood directly across the old King’s Highway from Ellison’s home lists a small account—just a few dollars in 1837—for “Ellison’s Stephen.” For a little molasses, tobacco, and whiskey, Stephen repaired and sharpened several plows.122 Although Ellison allowed Stephen to work for a few luxuries, he clearly was not offering him the same opportunity the white William Ellison had provided his slave April. For any slave who reached for more, William Ellison of Stateburg turned to a slave catcher.

While Ellison withheld the ultimate reward, he did not scrimp on his slaves’ medical care. They received the best medical attention available, administered by Dr. Anderson, who began treating the Ellisons and their slaves as early as 1824. From then until the Civil War, Dr. Anderson’s meticulous records indicate that he made hundreds of visits, sometimes at night, to Ellison’s slaves, almost fifty of whom he mentioned by name.123 Among other things, the doctor extracted Sam’s tooth, purged Augustus, cupped John, dressed Tom’s hand, lanced Washington’s whitlow, amputated Abram’s leg, bled Ben, delivered Elsey, “cured” Tunic’s gonorrhea, lanced a “negro man’s abcess,” delivered Charlotte “with instruments in [a] case of difficult labor,” set the fractured arm of a child, set the fractured thigh bone of a man, removed a splinter from a boy’s arm, and treated Stephen’s “case of syphilis.” He also prescribed a wonderful variety of medicines, including laudanum, hartshorn, sulphur soda, blistering plasters, cathartic powders, Peruvian bark, camphoratic mixtures, gum camphor, spirit of nitrate, cream tartar, myrrh, calomel, spirit of lavender, quinine bitters, and “blue pills.” While it is questionable whether such close attention was always a blessing, Ellison clearly did not neglect his slaves’ health. Nor did he give up quickly when a slave failed to respond to treatment. In 1837, for instance, Dr. Anderson made twenty-nine visits to Jacob. Whether Ellison acted out of financial self-interest or personal concern or both, he spent as much on his slaves’ medical care as most planters. Even the lordly Hamptons, whose plantations just east of Columbia held several times as many slaves, spent little more. In 1833 Dr. Josiah Nott charged Wade Hampton II $329 for treating his slaves at “Woodlands,” “Millwood,” and elsewhere.124 In 1844 William Ellison paid Dr. Anderson $212, most of it for attending his slaves.125

Ellison furnished medical care for all his slaves, but he was more selective in providing for their spiritual lives. Reverend Augustus L. Converse and other rectors of Holy Cross Episcopal Church ministered to only a few of Ellison’s slaves. Ellison saw to the baptism of six of his slaves in his own church. In 1844 John was baptized; in 1850, Sarah and Nancy Ann; in 1853, Jacob; and in 1861, Sarah Ann and Virginia.126 These baptized slaves were somehow favored by their master, perhaps because they were house servants (as Sarah almost certainly was) or because they were hard-working craftsmen who had earned Ellison’s respect. Other Ellison slaves may have attended services at Holy Cross, either on Sundays, when they would have sat in the gallery, or on those rare evenings when the Reverend Converse preached a special service for slaves.127 Since Ellison’s church stood within a mile of his slave quarters and the services never conflicted with the work day, attention to the religious lives of his slaves would not have cost Ellison a cent. The difference between the dozens of slaves treated by Dr. Anderson and the half-dozen baptized by the rectors of Holy Cross is a rough index of the distance that stood between Ellison and his slaves, a distance both parties probably helped maintain, each for their own reasons. Given the choice, many of Ellison’s slaves may not have seen spending Sunday at his church as something that would do as much for their souls as playing with their children, visiting with friends, or doing almost anything to keep a few hours for themselves.

The Ellisons indulged certain slaves in small ways, much as white planters occasionally granted little favors. Correspondence between members of the Ellison family reveals that from time to time on their visits to Charleston they picked up items for their slaves. In 1857, for example, William Jr. asked his brother Henry to “Get a hankerchief [sic] for Charlotte.” He also passed on a request from Gabriel, who asked Henry to bring back some “lether booties” for his wife.128 When the Ellisons wanted to send something to a family member in Charleston, they sometimes chose a slave to deliver it, and their choice of messengers indicates a certain sensitivity. “This will inform you that Isaac has arrived safe bringing the shoes, for which you have my thanks,” James D. Johnson, William Ellison’s old friend, wrote from Charleston in December 1858.129 Johnson said that Isaac had “reported himself daily to me and has conducted himself properly according to request.” After mentioning that he expected to send Isaac by train the next day, Johnson added, “His parents begs to present their thanks to you for permitting him to see them. The old man has been working for me and requested me to write you to let him come. I intended to have done so, but your sending him has made it unnecessary.” Young Isaac evidently made the trip to the city more than once and may have grown a bit bold, for in February 1860, Johnson’s son, James M. Johnson, wrote, “I was glad to hear that Isaac returned and hope he has seen his folly.”130 By the end of the year Isaac was back in the Ellison family’s good graces, for Johnson declared, “I expect to bring something for Isaac from Fanny, which may be an inducement for him to bring the cart to the depot.”131

These small favors must have been reserved for a special few, and even for them, rare. A privileged relationship with the Ellison family had its little rewards, but it also brought special demands and dangers. While on a trip to Charleston, Eliza Ann instructed Sarah, who belonged to Eliza Ann’s father but who served her, to “clean out the Fowl house properly & bury the contents in the poultry lot adjoining.”132 Eliza Ann’s husband, James M. Johnson, demanded, “Do see that Sarah behaves herself & salts the creatures regularly.”133 Somehow Sarah failed to behave herself to William Ellison’s satisfaction, and she was the only slave he singled out to be sold at his death.134 Ellison’s field hands did not receive handkerchiefs and boots from Charleston or special instructions from 100 miles away, but, so far as we know, they were not sold away either.

What little evidence we have suggests that Ellison’s mastery was neither particularly mild not particularly harsh. With the major exception of the apparent sale of slave girls, his slaves suffered the usual rigors of bondage. Despite his own history, Ellison did not view his shop and plantation as halfway houses to freedom. He never permitted a single slave of his to duplicate his own experience. No shred of evidence indicates that he felt the tug of racial affinity, no document hints that he considered his slaves members of an extended plantation family. Ellison’s ancestry offered immunity to no slave, and his definition of family stopped far short of the quarters. Everything suggests that Ellison held his slaves to exploit them, to profit from them, just as white slaveholders did.