On January 11,1989, Ronald Reagan delivered his farewell address to the nation. Characteristically mixing personal modesty with patriotic grandeur, he rejected his nickname, “The Great Communicator.” He explained: “I communicated great things, and they didn’t spring full bloom from my brow, they came from the heart of a great nation—from our experience, our wisdom, and our belief in the principles that have guided us for two centuries.” Further correcting the historical record, the president preferred labeling his era “the great rediscovery” rather than “the Reagan revolution.”

Reagan celebrated two great recoveries: the economic recovery that produced nineteen million jobs and the morale boost that restored America as the world’s leader. Still sensitive to the media pounding he endured, he insisted: “What they called ‘radical’ was really ‘right.’ What they called ‘dangerous’ was just ‘desperately needed.’”

Ronald Reagan, the man who called the Soviet Union the “evil empire,” rarely pulled punches rhetorically. He knew the “Reagan Revolution” label was catchier, more resonant, more historically flattering. Was this a final burst of modesty as the first president to complete two terms in office since Dwight Eisenhower retired?

Reagan’s preference for “rediscovery” not “revolution” reflected a characteristic cautious streak, especially in domestic policies. It was not just that he liked rooting his actions in the rich soil of American history nurtured by enduring wellsprings of American values. He understood Americans’ ambivalence about revolutions. Having rejected England with a conservative rebellion, Americans spent decades fighting the results of the Russian Revolution. It was particularly awkward for conservatives to pose as revolutionaries.

Reagan also knew that his governing approach had been more nuanced, more consensus-driven, less transformative than the grandiose title of “Reagan Revolution” implied. Reagan’s administration was never as radical as he occasionally promised, conservatives desired, or liberals dreaded. Reagan offered more of a restoration than a revolution, more of a reorientation, shifting slightly toward a less liberal future than a repudiation of the past, including the Great Society. If historians judged the Reagan era on its most sweeping terms—or by the goals he and his most conservative supporters articulated—the Reagan Revolution was a dud. And if historians judged by the critics’ fears—and doomsday warnings—about a return to back-alley abortions, mass hunger, institutionalized sexism, and the bad old days of Jim Crow, the Reagan Revolution also fizzled.

In more concrete terms, there were changes in the government’s tone, the military’s size, many federal judges’ ideologies, America’s approach to the world, especially the Soviet Union. In many critical areas, Reagan and the Republicans neutralized the government’s decades-old role as regulator, enforcer, and to liberals, force for good, but to conservatives, obstacle to progress. Still, Reagan only slowed the government’s growth rate; he did not stop the expansion. The federal budget, which was $590.9 billion in 1980 with $391 billion spent on domestic needs, was $2,655.4 billion in 2006, with $1,872.8 billion devoted to domestic needs. Under Reagan, the highest tax rates dropped dramatically, but the effective federal tax rates for all households were 22.2 percent in 1980, compared with 20.5 percent in 2005. Examining social issues, abortion remained legal in America, although the annual numbers dropped from 1,297,606 in 1980, meaning 25 per 1,000 women, to 830,577 in 2004, 16 per 1,000 women.

Thanks to the Reagan Reconciliation, the cultural revolution of the 1960s continued, despite Reagan’s denunciations of New Left excesses. Warnings of a “backlash” against blacks, women, and gays were overstated, as was the caricature of Reagan as a racist, sexist, homophobe. The number of African American politicians nearly doubled from 5,038 in 1981 to 9,040 in 2000. The percentage of women politicians serving in House, Senate, and statewide offices more than doubled from 10.5 percent in 1981 to 24.1 percent in 2007. By 2008 a woman, Hillary Clinton, competed against an African American, Barack Obama, for the Democratic presidential nomination. And not only were millions of gays living comfortably out of the closet, gay marriages and civil unions were openly discussed and legalized in some states, marking a dramatic breakthrough.

What drove the Reagan Revolution and what limited it, or morphed it, into a “great rediscovery”? To understand this we need to appreciate the powerful inertia—and widespread popularity—of the post-New Deal dimensions of government, the peculiar dynamics of the 1980s, and Ronald Reagan’s strengths and weaknesses as a leader.

For all the 1970s’ political, economic, social, and cultural discontent, the United States remained remarkably stable. Despite the twentieth-century expansion of governmental and specifically presidential prerogatives, the president was no dictator. The Constitution carefully distributed power among the Congress, the courts, and the presidency on the federal level, while encouraging a tug-of-war between the states and the national government locally. These checks and balances limited the changes Reagan or any president could implement. Reagan’s key aide in trimming the federal budget, the Office of Management and Budget’s director David Stockman, would mourn the limits of presidential power. After watching his efforts to trigger a conservative revolution falter, Stockman complained that America’s Constitution fragmented government power so much it prevented substantive reform.

Further frustrating radical conservatives was modern Americans’ addiction to big government and the New Deal-Great Society status quo. Americans often opposed governmental goodies others received, while ignoring their own appetites. Business leaders grumbled about welfare abuses while blocking Stockman’s proposals to cut corporate subsidies. Farmers muttered about all the money going into the ghettoes—without even purchasing social peace—while protecting anachronistic agricultural subsidies lingering from World War I.

Ultimately, most Americans acknowledged that, despite all the government’s inefficiencies, America’s big government also accomplished great things. By 1980, the half-trillion-dollar-a-year federal budget ate up nearly one-quarter of America’s gross national product. Spending on all levels of government consumed 36 percent of the GNP. Beyond the military, more than one million federal government workers distributed billions of dollars in handouts to farmers and physicians, exporters and importers, small businessmen and major corporations. Dozens of federal agencies, from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to the Office of Labor Management Standards, supervised, regulated, and micromanaged American life.

More and more Americans bristled as private businesses spent more than $100 billion responding to the flurry of bureaucratic regulations generating ten billion pieces of paper annually. The heroic New Dealers of the 1930s and the idealistic Great Society social activists of the 1960s now seemed to be replaced by the arrogant, out-of-touch federal bureaucrat. Many citizens resented working nearly half the year to pay the government, especially amid hyperinflation and steep interest rates. It became easy to believe the large federal budget deficits and burdensome federal regulations were strangling the economy.

Yet this insatiable Mr. Hyde, devouring hardworking Americans’ tax dollars, was also a Dr. Jekyll feeding the hungry, housing the homeless, healing the sick. In 1980 one out of every two American households received some federal, state, or local government support, 37 million individuals accepted Social Security assistance, 50 million children attended 170,000 schools, and a quarter of a billion Americans enjoyed using 29,500 post offices, one million bridges, and four million miles of roads.

Nearly half a century after the New Deal, most Americans looked naturally to Washington to solve all problems. Even clear state or local questions regarding abortion, the death penalty, and crime frequently became national controversies. The Supreme Court’s ever-expanding purview and the president’s centrality in any political discussion nationalized these and other local issues.

Reagan continued his winning election strategy as president. That meant that from the start he frustrated conservatives. His preference for the smile over the scowl, the joke over the jab, flag-waving over pot-stirring, general consensus over ideological purity made for a happier country and unhappy partisans. Reagan filled his cabinet with mainstream business-oriented conservatives such as Donald Regan from Wall Street as secretary of the treasury, and old Nixon-Ford hands such as Caspar Weinberger as secretary of defense and Alexander Haig as secretary of state. The conservative grumbling that had begun during the campaign intensified. “Let Reagan be Reagan,” they shouted. But in seeking the mainstream, in governing from the center, Reagan really was being Reagan.

At his inauguration, Reagan clarified that “it is not my intention to do away with government. It is, rather, to make it work—work with us, not over us; to stand by our side, not ride on our back.” Reagan wanted to recalibrate the relationship between the government and the people, saying: “We are a nation that has a government—not the other way around.”

Central to Reagan’s patriotism was his optimism. He loved telling the story of two brothers. The favored brother received a beautiful blue bicycle for Christmas and grumbled that it was not red. The mistreated brother, having received a roomful of horse manure, plunged in happily, believing that so much manure must be a sign of a really big horse. “It is time for us to realize that we are too great a nation to limit ourselves to small dreams,” Reagan said during his inaugural, repudiating Carter’s malaise warnings. Reagan called for “an era of national renewal,” challenging Americans to “renew our determination, our courage, and our strength. And let us renew our faith and our hope.”

Reagan’s inauguration brought the conservative movement to great power and prominence. In their wilderness years, cut off from the Harvard-Brookings-New York Times nexus, conservatives had developed an alternative intellectual universe. Ideologically motivated, bankrolled by frustrated corporate chieftains and entrepreneurs, an intricate network of intellectuals and strategists inhabited an overlapping world of think tanks and journals. The National Review, Human Events, American Spectator, Commentary, the Public Interest, the National Interest, and the essential Wall Street Journal circulated and recycled articles. Many writers were scholars affiliated with conservative think tanks including Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, the American Enterprise Institute, Georgetown University’s Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Heritage Foundation, an aggressive newcomer focusing on Congress and the press. Marginalized by the overwhelmingly liberal university culture, these entrepreneurial ideologues improvised. The Heritage Foundation’s Academic Bank organized computerized lists of 1,600 scholars ready to mount ideological warfare at the push of a button.

Reagan’s inauguration shifted the conservative movement’s center of gravity to Washington, DC. No longer the symbol of evil to conservatives now that they were in charge, the capital city suddenly seemed inviting. Even as they vowed not to “go native,” these young conservatives followed the paths of their New Deal and New Frontier predecessors. The Reaganauts established roots in Washington, creating a shadow government when Democrats returned to power, while pushing Republican administrations to the right.

Weeks before the inauguration, the American Enterprise Institute hosted a week-long conference. The new stars in the political firmament gleamed brightly as conservative intellectuals pitched big ideas to newly appointed officials, and wealthy businessmen wrote big checks. The highlight of the conference was the requisite—for that crowd—black-tie dinner, featuring the president-elect. “I want you to know that we’ll be looking closely at your observations and proposals,” Reagan cooed, telling the conservatives what they wanted to hear, promising a close “working relationship.”

Over the next eight years, hundreds of “movement conservatives” would work for the Reagan administration. Many of these believers, Secretary of Education Terrel Bell recalled, “proclaimed their ideological identity on cufflinks and neckties. Their logo was the profile of Adam Smith.” These ideologues treated Bell contemptuously, he bristled, as someone heading “a department sired by Jimmy Carter, mothered by Congress, delivered by the National Education Association functioning as an activist midwife and publicly designated for abolition.”

Like a privately held corporation, the modern presidency ostensibly reflected the boss’s desires, but the hundreds of key appointees in the executive branch, managing thousands of government workers, had wide discretion. Franklin D. Roosevelt had fewer than 100 White House staffers, only 71 presidential appointees in 1933, and 50 different agencies reporting directly to him; half a century later, there were more than 350 White House staffers, 600 presidential appointees, 1,700 employees in the Executive Office of the President, and approximately two million governmental employees overall. Even without a president as open to delegating and taking direction as Reagan, the inauguration marked a sweeping changing of the guard, the debut of Ronald Reagan, Inc.

The efficiency of Reagan’s White House initially rested on the leadership equivalent of a three-legged stool. Deviating from the Nixon-Ford trend toward concentrating power in one dominating chief of staff, a triumvirate led. The patrician chief of staff, James A. Baker III, a crony of Vice President George Bush, represented the Republican establishment’s stability and the corporate community’s financial interests. The slick deputy chief of staff, Michael Deaver, a confidante of Nancy Reagan from the world of public relations, focused on the Reagans’ personal needs and the president’s political image. And the professorial Edwin Meese III, who had advised Reagan as governor, was the ideologue. Baker’s corporate sensibilities and Deaver’s image-making calculations tempered Meese’s conservatism. These three headed a Reagan team that was moderate enough to frustrate conservatives but conservative enough to terrify liberals.

The triumvirate’s initial success helped feed the Reagan legend. Many critics first mocked Reagan’s work ethic, as he boasted about working nine-to-five, saying, “I know that hard work never killed anyone, but I figure, why take the chance?” But his strategy of serving as a visionary CEO rather than a Jimmy Carter-like micromanager doling out playing time on the White House tennis courts, soon charmed reporters—and business executives. During the second term, when one autocratic, controversial chief of staff, Donald Regan, replaced the triumvirate, Reagan’s hands-off management style would be considered more problematic.

As the Reaganites marched into Washington, issuing marching orders to the nation, Democrats remained shell-shocked. The two true-blue conservative cabinet members among the mostly moderate millionaires, David Stockman and James Watt, represented two competing impulses within conservatism. Stockman, the Office of Management and Budget director, was a technocrat with the soul of a calculator. He focussed on cutting the budget to shrink government. His methods tended to be systematic, rational, encyclopedic, delving into the complexities of the federal budget to cut, cut, cut. James Watt, on the other hand, was a fire-and-brimstone conservative with the soul of a preacher—and the subtlety of a hurricane. As a secretary of the interior hostile to environmentalism, he represented the conservatives’ broader social agenda to roll back the sixties revolution and reinvigorate capitalism. Watt outraged environmentalists by selling off public lands, resisting efforts to declare species endangered, encouraging more mining, drilling, and developing, while denouncing liberals as socialists.

Reagan launched his administration with some great news—and some bad news. The great news was that during his inauguration, the Iranians finally freed their diplomatic hostages. Ayatollah Khomeini gave the most conservative, nationalistic, and aggressive American president in a generation a welcome gift. Reagan reinforced his patriotic paeans with a hostage homecoming. Many Americans decided that Reagan’s more muscular rhetoric scared the mullahs, further legitimizing the conservative revolution.

Weeks later, on February 5, Reagan delivered sobering news on national television. The economy was even worse than he feared. Reagan used this news to justify even more sweeping budget cuts and tax cuts, challenging Americans to revolutionize their government.

Reagan toned down his conservatism with compassion, or at least the politically popular appearance thereof. In legitimizing “entitlements’” and maintaining the “social safety net,” Reagan accepted the strong American consensus supporting the welfare state. David Stockman did not “think people are entitled to any services.” Reagan, the child of Depression, acknowledged the government’s responsibility to protect the “truly needy.” Early in February Reagan deemed untouchable seven basic social programs serving 80 million people, costing $210 billion annually: Social Security’s Old Age and Survivors Insurance; Medicare’s health program for the elderly; the Veterans Administration disabilities program; Supplemental Security Income for the blind, disabled, and elderly poor; school lunch and breakfasts for low-income children; Head Start preschool services; and the Summer Youth Jobs Program. This pronouncement limited Reagan’s revolution. With entitlement programs consuming approximately 60 percent of federal expenditures, and half of these programs subject to automatic Cost of Living Adjustments (COLAs), Reagan could only budget-cut on the margins.

A multifront political war began. Republicans and Democrats clashed in Congress. Liberals and conservatives dueled on the opinion pages of newspapers. And voters looked on astounded as David Stockman questioned many of the New Deal’s governing assumptions and most basic programs, but then Reagan, or one of his cabinet members, backpedaled, protecting the status quo more than Reagan’s reputation suggested.

Still, his rival Tip O’Neill denounced Reagan’s aggressive, heartless, “Godfather tactics.” The Speaker of the House alternated between grumbling about such “cold, tough and cruel” White House politicking “for the wealthy of America” and lamenting that Jimmy Carter was never so effective. O’Neill and his aides enjoyed ridiculing the president, mocking Reagan’s intelligence with zingers about Reagan’s reliance on note cards or coaching when lobbying Congress. Yet in the arena of congressional relations during that first year, Reagan’s intelligence shone through, in the persuasive speeches he delivered, in the subtle assessments he offered his aides of legislators’ positions after calling them one more time, and in the quick responses he filled out on forms staffers prepared summarizing congressional correspondence. To one congressman’s “strong opposition” to Reagan’s proposal for reforming Social Security, the president wrote “can he do better?” To another complaint about “a lack of leadership” in the past regarding refugee issues, the president joshed “but we don’t have a lack of leadership now—or do we?”

Reagan’s greatest contribution to the budget fight was in public as the “seller” he saw himself to be. Repudiating the Johnson-Nixon-Ford-Carter legacy of failure, Reagan took command immediately. He impressed large and small audiences, demonstrating the eloquence, charm, and unexpected doggedness that would shape his reputation. Skeptics were surprised that this supposed clod was quite witty; that this supposed fanatic was quite nimble—and adept—at defusing conflict. When asked about labor union opposition, he quipped, “I happen to believe that sometimes they’re out of step with their own rank and file. They certainly were in the last election.” When asked while chatting with reporters on Air Force One to assess a major economic address he had just delivered, the old actor admitted he was pleased, saying “but then you’re always in good spirits when you figure you got by without losing your place or forgetting your lines.”

Nevertheless, the salesman-in-chief failed to make the sale. The intense congressional and media backlash damaged Reagan’s poll ratings by mid-March, barely two months into the administration. Polls also showed a dichotomy that would persist throughout his tenure. Reagan himself was much more popular than his programs; more Americans liked Reagan than agreed with him.

While Reagan was selling his program to union leaders at the Washington Hilton on March 30,1981, he was shot. A disturbed twenty-six-year-old, John Hinckley, hoping to impress the actress Jodie Foster, began firing as Reagan exited the hotel. One Secret Service agent, one local police officer, and one Reagan aide, White House Press Secretary James Brady, fell to the ground, wounded. One bullet glanced off the armored limousine’s door and hit Reagan. The slowed momentum of the deflected shot saved his life—but the bullet came dangerously close to his heart. Unbeknownst to most Americans, the president of the United States nearly died.

Acting with remarkable aplomb, Reagan walked stiffly from his car into the emergency room, to reassure his constituents, then collapsed. Before succumbing to the anesthetic, he delivered the first of many quips that would help build his legend. Looking at the doctor rushing him into surgery, the old actor—and partisan— asked, “I hope you’re a Republican.” The head surgeon, Dr. Joseph Giordano, a liberal Democrat, supposedly replied, “Mr. President, today we are all Republicans.”

The failed assassination made Reagan appear larger than life and his program more politically popular than it otherwise would have been. Reagan had already emerged as a man most Americans loved to like. After the shooting, Americans rallied around their president, their country, and his policies, at least for a few months. By May 8, just over one hundred days after the inauguration, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives passed Reagan’s budget 270–154. HOUSE PASSES DEEPEST BUDGET CUT IN HISTORY, the Los Angeles Times proclaimed, declaring the sixty-vote margin A BIG VICTORY FOR PRESIDENT.

The Reagan revolution’s first round reduced the personal income tax rate by almost one quarter, dropped the capital gains tax from 28 to 20 percent, yielding an unprecedented tax reduction of $162 billion. By the summer, Reagan had cut $35 billion in domestic spending from Jimmy Carter’s request, while increasing military spending. By 1986 the defense budget would be twice 1980’s allocation. “We have done more than merely trim the federal budget and reduce taxes,” Reagan rejoiced. “We have boldly reversed the trend of government. As we promised to do in 1980, we have begun to trust the people to make their own decisions, by restoring their economic independence.”

That summer of 1981, Ronald Reagan moved dramatically to the center on social issues. On July 7 he nominated the first woman to the Supreme Court. Sandra Day O’Connor was an Arizona Republican warmly endorsed by Senator Barry Goldwater. Many conservatives worried she was too moderate. “I am going forward on this first court appointment with a woman to get my campaign promise out of the way,” Reagan told William F. Buckley, in a rare acknowledgment of brusque political calculation. Reagan added: “I’m happy to say I had to make no compromise with quality.” Reagan, who prided himself on being even-tempered, bristled when local Arizona conservatives questioned O’Connor’s commitment to the “pro-life” movement. In fact, O’Connor became an important swing vote who helped maintain the emerging liberal status quo on abortion and other issues dear to conservatives.

Characteristically, a few weeks later, Reagan countered by moving rightward. In early August, the Air Traffic Controllers’ union, called PATCO, declared a strike. Reagan had befriended the union leaders during the campaign but had warned them during negotiations that federal government employees were banned from striking. When the controllers walked off the job, for Reagan it became a simple issue. “That’s against the law,” he noted in his diary. “I’m going to announce that those who strike have lost their jobs & will not be re-hired.”

Reagan was taking a bold risk. At the height of the summer travel season, millions of stranded Americans could have blamed him for ruining their vacations. More sobering than the political danger was the actual danger. A major airline crash blamed on incompetent replacement workers Reagan’s intransigence imposed on the system could have been disastrous.

Instead, Reagan’s luck held; on this issue he demonstrated perfect political pitch. Nearly half a century after the labor gains of the 1930s, the public had lost patience with unions. Labor leaders no longer appeared to be noble warriors delivering basic rights to the great unwashed, but corrupt insiders lining their pockets at their members’—and the public’s—expense. Reagan rode this backlash. On August 4, the day after Reagan read the “written oath each employee signs” not to strike, a third of the controllers had returned to work. Flying was 65 percent normal. The next day nearly 40 percent worked, with air traffic at 75 percent normal.

Reagan’s strong stand against the air traffic controllers devastated the already weakened labor movement but provoked widespread applause. In many ways, this move defined his first year in office. Reagan showed there was a new sheriff in town. Millions of Americans welcomed such affirmative leadership after decades of drift. Corporate leaders on both sides of the Atlantic also applauded the pro-business stance. Years later, when explaining how America tamed inflation and emerged from the economic doldrums, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board at the time, Paul Volcker, would call the PATCO showdown a turning point in America’s economic, psychic, and patriotic revival.

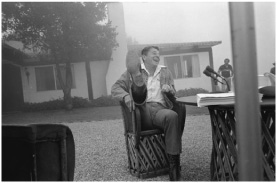

On August 13, shortly after his PATCO star-turn, Reagan signed his tax-cutting legislation at his California ranch. The president of the United States wore a denim suit with an open-necked collar. Photographers captured him turning in his seat at an outdoor table with stacks of bills to sign and a microphone, kicking up a booted foot and beaming.

Ronald Reagan had a lot to smile about. This was the Reagan Revolution’s happy face. In eight months, he had silenced many of the doubts surrounding him while freeing Americans of some of the self-doubt that had been clinging to them. Americans were feeling prouder, more nationalistic, more in control, thrilled to have a president who was proud, assertive, and affirmative. Reagan’s assault on the ways of the New Deal and the Great Society was progressing. His tax cuts and his strike-breaking were popular. Ronald Reagan could claim he led Americans on a great rediscovery of their values—and of their common sense.

But close observers could also see the limits to Reagan’s don’t-rock-the-boat revolution. He had tweaked the governing New Deal status quo without really assailing it. Much of the budget fight remained about the margins of growth rather than the fundamental assumptions of what Reagan always called “big guvment.” And, as with the Sandra Day O’Connor appointment and other critical moves, Reagan recognized the needs to mollify the media, the Democrats, and the majority of American people who doubted his program, even if they liked him.

5. Ronald Reagan at his ranch after signing historic tax-cutting legislation on August 13, 1981.

The dramatic changes Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher implemented in Great Britain demonstrated President Reagan’s constraints—and more limited accomplishments. Thatcher became prime minister in 1979, eighteen months before Reagan’s inauguration. Like Reagan, she sought to cut the budget, reduce taxes, and diminish union power. But Great Britain’s welfare state was much more elaborate and entrenched. Nevertheless, Mrs. Thatcher had more latitude, given the prime minister’s control of the Parliament and Parliament’s primacy in the British system. Thatcher reduced the basic tax rate from 33 percent to 25 percent, dropping the top rate from as high as 98 percent—83 percent on wages and a 15 percent surcharge on interest and dividends—to 40 percent. She opened capital markets, confronted many more unions than Reagan did, and privatized some major British industries including British Airways and British Steel.

Still, while Thatcher’s record may eclipse Reagan’s, her calls for revolution reinforced his. That both Great Britain and the United States had vigorous, conservative leaders calling for small government and freer enterprise generated an impression that liberalism was retreating and that the conservative revolution was global. Thatcher visited Reagan on February 26,1981, a little more than a month into Reagan’s tenure. Reagan greeted her warmly, saying “We believe that our solutions lie within the people and not the state.” Thatcher replied: “Mr. President, the natural bond of interest between our two countries is strengthened by the common approach which you and I have to our national problems. . . . We are both trying to set free the energies of our people. We are both determined to sweep away the restrictions that hold back enterprise.”

6. President Reagan greeting British prime minister Margaret Thatcher at the White House, February 26, 1981.

Reagan was already mastering his governing formula. He understood that in the modern American politics of spin, the illusion of action was often as important as the action itself. Reagan was happy to talk right and govern center, to champion conservatism but act moderately, to hear others talk about a “Reagan Revolution,” but keep the discussion more limited to his Great Rediscovery.

Thus, the revolution did not follow Reagan’s stated script. The ship of state did not veer sharply to the right. However, Reagan helped reorient America, changing the country’s approach to questions of budget, big government, and the welfare state. A new vocabulary of budget cutting, tax cutting, and deregulation took hold. In the long term, these shifts changed America’s trajectory. Simultaneously, the resulting great prosperity of the 1980s fed a more individualistic approach and intensified many of the trends toward a more consumer-driven, celebrity-oriented, and selfish society—which Reagan came to personify in many ways, even as he tempered it with a veneer of traditionalist rhetoric.