6

“War, Insurrection and Riot”

WHILE SID HATFIELD and the miners had reason to be grateful for their friends in Mingo County, the situation was very different in Charleston, West Virginia’s capital. Indeed, when the new governor, Republican Ephraim Morgan, and the new legislature arrived there to take over the state government in March of 1921, just as the jury in Hatfield’s trial was reaching its verdict, anyone friendly to Hatfield or to the UMW cause in general would have been very hard to find.

Not that the miners wasted any tears on the departure of John Cornwell from the governor’s office. But their bitter experience with Cornwell’s reign had led the union and its supporters down a risky political course, the costs of which they were only beginning to bear.

In the spring of 1920, even as they were mounting their drive to organize the mines of southern West Virginia, the mine workers union and its allies had plunged into a separate but related contest in the political arena. It might seem surprising that in the midst of their critical campaign to win new members, the forces of labor would divert attention and resources to some other objective. But if the union and its backers had learned any lesson in the past few years, it was how important political power was to their chances of success.

They all remembered that they had helped to make Cornwell the first Democrat to hold the governorship of their state in the 20th century. Now they saw in Cornwell a man who too often used his power to curb their potential in the state. His view of the UMW seemed darkened by his increasing fixation with the threat of left-wing radicalism, an obsession reflected in his speech in 1919 warning that organized labor was conspiring to impose communism upon the United States.

Looking back on the struggle over unionization in West Virginia near the end of his term Cornwell would say: “I had no part and parcel of it so far as lending aid or sympathy to either side went. It seemed to me to be my sole duty to preserve order, in so far as I was able to do so.”

To West Virginia’s disappointed union leaders, who had helped to put Cornwell in office, that chilly neutrality represented a betrayal, and they were not shy in making their feelings known during his tenure. John L. Lewis had called for his resignation. Fred Mooney had berated Cornwell as a narrow partisan and said his administration had been thoroughly discredited. Frank Keeney had written to Secretary of War Newton Baker to complain of Cornwell’s bias.

Some rank-and-file members were more compassionate. “While no money could hire me to vote for you again,” one UMW member wrote, “still I respect you and your laws as a true American should.” But Cornwell was too seasoned a politician not to realize that such mild admiration did not promise much for his political future. Stripped of the labor support that had helped win his narrow victory, plagued by glaucoma, which badly impaired his vision, and worried about the need to provide for his family’s future, he announced that he would take his leave from politics as his term ended.

With Cornwell departing the scene, the Democrats faced a year in which the tides nationally were running against them, and settled on a little-known political timeserver, Arthur B. Koontz, whom union men viewed as Cornwell’s stooge, as their choice for governor. On the Republican side, the party’s favorable prospects for victory set off a bitter three-way contest for the nomination. Most of the GOP establishment backed Ephraim Morgan, a conservative state judge from Marion County in the northern part of the state. But the previous Republican governor, Henry Hatfield, threw his support to Paul Grosscup, an oil and gas executive from Charleston, who also had the backing of the mine owners of southern West Virginia.

To the left of both of these contenders was a respected veteran of the law and of government, Samuel B. Montgomery, who had bona fide liberal credentials. He was a former leader of the state federation of labor, counsel for the United Mine Workers, and commissioner of labor in the Hatfield Administration. Given these choices, it was not hard for UMW leaders to conclude that Montgomery represented their sole hope. So they turned their backs on their former allies in the Democratic Party and mounted a major effort to help Montgomery win the Republican nomination.

On primary day, May 25, the week following the Matewan massacre, the early returns showed Montgomery running strong among GOP voters, and many in District 17 headquarters were jubilant. But later results showed he had finished third, behind Morgan, the winner of the nomination, and Grosscup. Montgomery lost even in Mingo County. On the following day, when the union field workers returned to headquarters, Keeney chided them. “You guys didn’t make much of a showing,” he remarked.

“You should get a look at the river and you’ll see what sort of a showing we made,” was the reply from one disillusioned field man. “The ballots are still floating. They didn’t even bother to turn them in.” Union men claimed that in the open-shop counties the ballot counting was monitored by company guards, who were also deputy sheriffs, and who made it their business to invalidate as many Montgomery ballots as possible.

In the general election, the union forces, seeing little to choose between the two major party candidates, again backed Montgomery, who ran as an independent. A banner hung across Matewan’s main street reflected labor’s sentiments. It urged support for James M. Cox, the Democratic presidential candidate and his young running mate, Franklin D. Roosevelt of New York, the Democratic candidates for county and district office and Independent Samuel B. Montgomery for governor. Montgomery campaigned in Matewan, making a particular point to visit with the local hero, Sid Hatfield. In the statewide balloting he got 81,000 votes, 15 percent of the total. It was a respectable showing in itself. But its main significance was that it denied victory to the Democrats, whose candidate, Koontz, got 185,000 votes, compared with 242,000 for the victorious Morgan. Most politicians concluded that Montgomery’s vote, nearly all of which presumably would have gone Democrat, had enabled Morgan to regain the governorship for the GOP.

When the last ballot had been counted, the union forces realized that the state house in Charleston had become enemy territory. Whatever Cornwell’s faults, at least they could remind him about the promises he had made to gain their support; the 52-year-old Morgan, whose service on the state’s public service commission had stamped him as a faithful servant of West Virginia’s business interests, and his fellow Republicans had not even pretended to any sympathy with the union cause. And in the wake of labor’s support for Montgomery, the Democrats who remained in the legislature had no reason to do trade unions any favors.

Cut off from the levers of power in Charleston, the UMW turned to Washington for help, making another bid for a Senate investigation. Senator Kenyon had turned down just such an appeal right after the Matewan shoot-out the year before. Nevertheless in February of 1921, with the union men still walking picket lines amidst intermittent violence, Frank Keeney came to Washington to personally lobby the senators and the press. “The Constitution has been kicked into the discard in West Virginia,” Keeney told reporters, insisting that the blame “can be laid at the door of the operators’ gunmen.” Keeney scoffed at charges that the miners had been shooting at state troopers and soldiers. “Let me tell you these miners are crack shots, and if they ever shot at a trooper more than twice he wouldn’t be alive.” What the union wanted, Keeney said, was “for a committee of senators to decide who is doing the shooting.”

The Senate did not respond. Instead, in the weeks before the legislature convened, new violence hardened public attitudes against the UMW. On February 19 a sustained gun battle between union miners and company guards at the Willis Branch coal company in Fayette County, about fifty miles east of Mingo, had brought an appeal for more state protection from the company. A few days later, Cornwell visited the nearby community of Willis Branch along with governor-elect Morgan and declared that the town had been “shot off the face of the map.” Homes that had not been burned or blasted with dynamite were riddled with bullets. The townspeople had fled and only stray dogs roamed the streets. Faced with what he would soon have to deal with, Morgan seemed shocked. “It is inconceivable that such conditions could exist in this day and age,” he said.

The not-guilty verdict that freed Hatfield and his co-defendants late in March generated a burst of euphoria on the union side. Hailing the verdict, the UMW Journal predicted that “it will really result in the complete elimination of the brutal gang of gunmen” who had ruled labor relations in West Virginia. To exploit the verdict and the celebrity of Sid Hatfield, the union produced a silent movie called Smilin’ Sid after the sobriquet he had acquired during the trial, which showed Constable Hatfield, his two guns on his belt, swaggering through the tent colonies and mining camps at the head of a squad of fearless union men.

But the rosy mood in union ranks was soon darkened when the newly elected legislature convened in 1921. One of the first items of business was passage of a bill, sponsored by State Senator Joseph Sanders, one of Sid Hatfield’s prosecutors, which made it possible to draw a county court criminal jury from the citizens of another county, thus nullifying the advantage union leaders and sympathizers, such as Hatfield, enjoyed in pro-union counties. A similar proposal had been defeated the previous session when labor still had some friends in the capital. The bill was too late to help the prosecution of Hatfield for the Albert and Lee Felts murders, but neither the union nor the operators doubted there would be more such trials. Among other blows dealt the union cause were measures doubling the size of the state police force, thus strengthening the governor’s hand in cracking down on strike-related violence, and setting the stage for reactivation of the national guard, in belated keeping of the pledge Cornwell had made to then War Secretary Baker earlier in the year.

With the cards stacked even more in their favor now than before the elections, the coal companies stepped up their importations of strikebreakers. For their part, the union miners, more desperate than ever, struck back with increasing fury.

All through the early days of that spring, union snipers, many hidden in the hills on the Kentucky side of the Tug, kept a steady rain of fire on the mining camps manned by strikebreakers. The White Star mining company at the town of Merrimack near Matewan was a particular flash point. Despite continuous sniping intended to shut down the mine, the company brought in fresh strikebreakers and maintained production. The strikers blew up the mine’s power plant, but White Star made repairs and resumed operations. Finally on Thursday May 12, 1921, one week short of the first anniversary of the Matewan shoot-out, the violence escalated and the union launched a full-scale attack, laying siege to the town. Scores of miners in the hills above the town cut down telegraph and phone lines and trained their guns on the buildings, the mines and the strikebreakers. The union attackers used a cow horn to control the assault; one blast signaled the start of shooting, with three blasts firing ceased.

Strikebreakers returned the fire, and the shooting soon spread. By one reckoning, some 10,000 shots were fired during the long day and night. Bullets ripped into the walls of nearby homes in Matewan, and in state police headquarters shells tore through a wall and smashed a mirror. Women and children hid in closets and fled their homes, for leaving the shelter of a house was dangerous. In Matewan, Harry C. Staton, a former justice of the peace and local prohibition officer, who had testified against Sid Hatfield in the Matewan shoot-out trial a few weeks before, was shot dead as he walked along the railway tracks near his home, and police arrested Calvin McCoy, a miner who had been one of Hatfield’s co-defendants.

Under orders from Governor Morgan, units of the recently expanded state police hurried to the scene in newly acquired automobiles. Although Colonel Arnold was still nominally in command of the state force, his background as a holdover Cornwell appointee and his reputation for independence did not stand him in good stead in the new administration. To handle this critical assignment in the labor hotbed of Mingo County, Morgan picked his own man, Captain J. R. Brockus.

Then forty-five years old, Brockus had enlisted in the U.S. Army as a private in 1890, served seven years in the Philippines, taken part in the China relief expedition in 1900, commanded an infantry battalion in France in the Great War and left service wearing a major’s gold oak leaves. An old AEF comrade had recruited him for the state police, which he joined with the rank of lieutenant. He won rapid promotion to captain thanks in part to his natural aggressiveness, a trait that, when displayed a few months later that year, would leave its mark on history.

But on this May Thursday in 1921, Brockus would encounter mostly frustration. The cars carrying him and his troopers to the battlefront in Merrimack bogged down in the spring mud. They put chains on the tires but finally abandoned them and set off on foot. Some of his men then came under sniper fire from both sides of the river and found themselves trapped, about one half mile west of the mining camp village of Sprigg, unable to move in either direction. It took five hours before they could escape, thanks to a long freight train that shielded them as they scurried into the woods, and then retreated back to Sprigg.

Another state police detachment headed for Sprigg on a passenger train, which also came under sniper attack. Terrified passengers huddled on the floor. The conductor refused to make the scheduled stop at Sprigg, and carried the troopers half a mile east of the town to the protection of a tunnel. But no sooner did the troopers leave the train than the heavy fire forced them also to flee into the woods.

At the close of the day, Brockus’s report to headquarters was grim: “The situation is serious, and unless steps are taken to disarm all persons on both sides of the river officers will be ambushed, houses shot up and murder committed by the wholesale.”

Brockus complained that he lacked the legal authority to restore order. “Arms and ammunition are being purchased daily from the local merchants and shipped in by express,” he told his superiors. “Under the present conditions we have no authority to take a rifle from a man whom we might meet on the public road with a load of ammunition going directly to the firing.”

The gunfire continued throughout the day and into the night. In Matewan the streetlights went out, and fearful families around the county slept on floors or in cellars. The next day, Friday, May 14, fighting spread to other towns along the Tug River and across the Tug into Kentucky, pitting union miners against strikebreakers and state police along a ten-mile front. One strikebreaker, Ambrose Gooslin, was wounded and another, Dan Whitt, was killed as they crossed railroad bridges over the Tug River. Both were shot at daybreak. But the gunfire was so intense that Gooslin lay on the bridge for hours until nightfall when friends finally dragged him to safety. He died two days later.

Normal life came to a halt in Matewan and the surrounding area. Stores and schools closed their doors and strikebreakers fled for their lives. At the height of the battle, Sid Hatfield patrolled the town with his friends, all heavily armed. Confronting the superintendent of the Stone Mountain Coal Co., who was overseeing the unloading of a rail car, Constable Hatfield ordered him to stop to avoid an attack by snipers. When he refused, they argued and Hatfield knocked the superintendent down. Some said he hit him with a rifle while Hatfield claimed he used only his bare hands and had “just slapped him down.” At any rate another criminal charge was filed against the constable.

Late on Friday, May 13, the second day of fighting, a deputy sheriff under flag of truce made his way to the outposts of the union miners in the mountains behind Matewan and won from them a promise to stop shooting if their foes would also lay down their guns. With that to go on, Brockus dispatched a well-known local physician, across the Tug to Kentucky to negotiate with the strikebreakers. After crawling a half mile under fire the doctor parleyed with the non-union miners, who agreed to call a truce. He returned to Matewan Saturday night May 14, where a relieved Brockus spread the word that the bloodshed was over.

The sustained outbreak of violence came to be known as the “Three Days’ Battle.” Frank Keeney later described the episode as “a shooting bee.” No one had an exact casualty count, but estimates ran as high as twenty deaths on both sides and Keeney was told on good authority that for eight days in the wake of the battle “they were bringing dead men out of the woods.”

Less than three months after the last elements of the 19th Infantry had been withdrawn, following the murder trial in Williamson, Federal troops once again were needed in West Virginia, or so Governor Morgan believed. Early in the Three Days’ Battle, Morgan had appealed for troops to General Read, commander of V Corps, a request that was backed up by Governor Edward Morrow of Kentucky. Since the direct-access policy had been revoked earlier that year, Read had no choice except to pass the request along to the White House. Meanwhile Republican Senator Howard Sutherland of West Virginia hurried to see the new president, Warren Harding, to support Morgan’s appeal. When Harding failed to respond immediately, Morgan pleaded for help again, this time directly to Harding himself. He made no attempt to disguise his impatience: “Are we compelled to witness further slaughter of innocent law abiding citizens with no signs of relief from the Federal government?”

Morgan may well have assumed that Harding, a solid Republican supporter of business interests, would leap at the opportunity to use the power of Federal government to crack down on the excesses of organized labor. But if Morgan did believe that, it was because he lacked an adequate understanding of who the nation’s 29th chief executive was and what he intended to do with his presidency. Harding, who had been in office barely two months when Morgan sought to burden him with West Virginia’s problems, was the quintessential middle-class man of postwar America.

Warren Gamaliel Harding believed in getting along by going along, without making a fuss or muss. A small-town newspaper publisher, he was a trustee of the Trinity Baptist Church, a member of the board of directors of almost every enterprise of consequence in his hometown of Marion, Ohio, a leader of fraternal organizations and charitable causes. His life exuded an aura of respectability that offered no hint of the future scandals that would besmirch his presidency. Harding harbored no ill feeling toward anyone and instead sought to make friends on all sides. Despite his many and diverse activities, he found time to organize the Citizen Cornet Band, available for both Democratic and Republican rallies and took an active part. “I played every instrument but the slide trombone and the E-flat cornet,” he once claimed.

He had an easy manner. People liked him and he did nothing to antagonize them. If the Republican bosses who helped him get elected wanted to make decisions about policy and appointments, he saw no reason to object. His matinee idol features, genial manner and particularly his sonorous voice and grandiloquent style helped him climb the political ladder. After one Harding speech on the floor of the Ohio Senate, the Ohio State Journal observed: “The speaker’s address was rich in grace of diction and his manner, earnest and forceful throughout, rose to the dignity of true oratory.”

But these gifts carried him only so far. Though he moved from the state senate to the lieutenant governorship, when he ran for governor he failed. Then in 1912 when many Republicans bolted their party and backed TR on the Bull Moose ticket, Harding stuck with the regulars and delivered the speech that nominated his fellow Ohioan, William Howard Taft.

Taft was doomed. But Harding’s loyalty to his party made up for whatever else he lacked in leadership gifts. Grateful Republicans rewarded him with their nomination to the U.S. Senate in 1914, the first year that senators were publicly elected, and Harding won easily over the Democratic candidate, State Attorney General Timothy S. Hogan, who fell victim to a wave of anti-Catholic feeling. “This is the zenith of my political ambition,” Harding declared on election night. The U.S. Senate he found to be a “very pleasant place.” But Harry Daugherty, his longtime friend and political manager, had higher ambitions for Harding than the senator had for himself. That Harding continually denied ambitions for the presidency did not disturb Daugherty.

“He will of course not say that he is a candidate,” Daugherty wrote a friend. “He don’t have now to do much talking or know much. Presidents don’t run in this country like assessors, you know.” Others looking at the man’s inner self might not necessarily see in Harding the qualities that would suit him for the office designed for Washington and graced by Jefferson and Lincoln. Daugherty, though, relied on the externals, which made Harding seem attractive and appealing. “He looked like a president,” Daugherty pointed out. And in the mediocre Republican field of 1920 and in the postwar mood that gripped America, that was just about enough.

Gaining nomination from a previously deadlocked Republican convention as a compromise choice, through backroom conniving that Daugherty had foreseen, Harding laid out his vision of the nation’s future. “America’s present need is not heroics, but healing,” he declared, “not nostrums, but normalcy, not revolution, but restoration, not agitation, but adjustment, not surgery, but serenity . . .” And so on and so forth. It would take only a quick glance at Harding’s s alliterative list of dos and don’ts to realize that intruding the majesty and power of the Federal government into what was essentially a local dispute was not likely to comport with his view of appropriate presidential actions.

Refusing to be stampeded by Morgan’s entreaties, Harding conferred with his secretary of war, John Weeks, then signed two separate proclamations of martial law, one for Kentucky and one for West Virginia, but did not issue either, pending further word from General Read. Read alerted the 19th infantry and Colonel Hall to the possibility of a return to Mingo County. Meanwhile, he sent his own intelligence chief, Major Charles Thompson, to Charleston to gauge the extent of the emergency.

Thompson met with Governor Morgan, with Mingo County officials and with the coal operators. It was indicative of the prevailing attitude among Army officers toward labor unions that Thompson made no attempt to consult with union officials. It did not take him long to conclude that the miners had caused a serious disorder. The question was whether the Federal government needed to intervene in either state. The answer for Kentucky, as Thompson soon realized, was obviously no. The governor of that state, as Thompson learned, had at his disposal a fully organized National Guard, including five companies of infantry and three troops of cavalry along with 300 deputy sheriffs. That certainly seemed sufficient.

West Virginia was a more complex matter. Its forces were puny by comparison with its neighbor, since despite the preliminary action by the legislature earlier in the year, the state had not yet gotten around to reestablishing its National Guard. But Thompson concluded that West Virginia’s failure to act was no excuse for it to seek Federal aid. “Authorities have not taken sufficiently active measures,” the major reported to General Read “and for purposes of both politics and economy, they have decided to rely on Federal protection.”

Thompson had another reason to advise against giving Morgan the troops he wanted. Twice before the Army had been sent to West Virginia to restore order, only to see violence erupt after the soldiers were withdrawn. Thompson believed that it would take a full declaration of martial law—putting the Army in full charge of law enforcement—for the arrival of the soldiers to achieve long-term results.

Harding was not prepared to take any such drastic action.

After meeting with his cabinet, he had a telegram sent to Governor Morgan explaining his decision. “The Federal government is ever ready to perform its full duty in the maintenance of the constituted authority,” the wire said. But it added that the president felt he would not be justified in sending troops “until he is well assured that the State has exhausted all its resources in the performance of its functions.” And of this, the White House made clear, Harding was far from convinced.

In the wake of Harding’s rebuff, Morgan finally did what he should have done all along, make use of West Virginia’s emergency public safety law, enacted in 1919. This allowed him to transfer authority for law enforcement in Mingo County from the sheriff’s department, whose deputies even under Blankenship’s replacement, A. C. Pinson, were suspected of siding with the strikers, to the decidedly less sympathetic state police, under Captain Brockus. On May 18, Pinson, in an official warrant submitted to Brockus, asserted that the labor disputes in the county had led to numerous breaches of the peace. “Murder by laying in wait and shooting from ambush has become common.” And since “there is now imminent danger of riots and resistance of the law,” which could not be suppressed by his own forces, the sheriff added, the resources of the department of public safety, which managed the state police, were required to restore order.

That same night, Mingo County authorities called a mass meeting in the county courthouse at Williamson to solicit volunteers for a “vigilance committee,” also dubbed a “law and order committee,” to reinforce the existing state police. The cream of Mingo’s middle class, some 250 businessmen, doctors, lawyers and every clergyman in town, answered the summons. They were the “better citizens” of Mingo County, “the men in business there and who have property there and were clamoring for protection,” as Brockus would later describe them.

The meeting opened with a chorus of “America.” “My country’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty,” sang the assembled “better citizens.” Dr. J. W. Carpenter, minister of Williamson’s First Presbyterian Church and leader of this law and order rally was well suited to the task, having often denounced the union leaders and their sympathizers as no better than murderers from his pulpit. President Harding had admonished Mingo County to use its own resources to clean its own house, Carpenter reminded the attentive burghers in his audience. Now each upstanding citizen must do his duty, just as many did during the Great War. “It is just as much a patriotic duty to clean up Mingo County as it was France,” the Reverend Carpenter declared. As for himself, let no one think that because of his status as a man of God he was not ready for this secular challenge. “I don’t know a thing about a rifle, but I am sure I can wield one, or a baseball bat if necessary.”

Lant Slaven, a partner in the law firm of Goodykoontz, Scherr and Slaven, whose client list was laden with coal operators, sounded the same note of civic responsibility. “Who knows how soon they will be firing on Williamson?” he asked. “There may be some losses among us, but who here would not be willing to sacrifice for the sake of law and order in Mingo County?”

Major Ike Wilder, commanding Kentucky guardsmen on duty along the Tug, showed up in full regalia, including spurs, to pledge his state’s full cooperation. Sheriff Pinson, who had just gotten off the phone with Morgan, passed on the governor’s enthusiastic endorsement and read a telegram: “No time should be lost in placing under arrest every person in the county who has engaged, aided or abetted in the recent murders, attempted murders and destruction of property.”

Just before the meeting closed, Captain Brockus arrived from a quick trip to Matewan, and strode to the podium like Caesar mustering the Roman legions. “Unless you have a rifle on your shoulder and are ready to do your duty, then we will have no order in Mingo County,” the captain declared. “Unless you show up to take your place, then there is no hope, but I know you will.” Brockus called for those men willing to serve the cause of law and order to stand. The response was overwhelming. “It seems to be unanimous,” Brockus declared triumphantly.

The next day, May 19, 1921, Morgan proclaimed martial law. It was the first anniversary of the battle of Matewan, and the terms of Morgan’s proclamation underlined how much ground the union and its members had lost since then. The governor declared West Virginia to be in a “state of war, insurrection and riot” and cited the inability of local law enforcement to maintain order. In one note of caution, intended to avoid judicial reversal of his decree, Morgan allowed the civil courts to function. But his edict banned the carrying of guns, ruled out public assemblies, meetings or processions and prohibited the publication of a newspaper or pamphlet “reflecting in any way upon the United States or the State of West Virginia or their officers or tending to influence the public mind against the United States or the State of West Virginia.” Appointed as the governor’s chief agent in charge of administering the martial law was Major Thomas. B. Davis, adjutant general of the state of West Virginia, who as a result of his new responsibilities would soon become known as the “Emperor of the Tug River.”

A man with the build of a stevedore and the face of a bulldog, Davis by the time of his appointment already had a long and stormy personal history in West Virginia law enforcement. Though the news would have shocked the union workers he fought against throughout his public career, Davis had once been a union man himself. Raised in Huntington, West Virginia, his first job out of high school was as an apprentice machinist at the Chesapeake and Ohio railroad yards, and he rose to become president of Huntington’s machinists union.

But in 1898, when the United States waged its “splendid little war” against Spain, Davis signed up with the 1st West Virginia Voluntary Infantry. He never heard a shot fired in anger, instead spending the war being shunted from one training camp to another. But Davis had developed a taste for military life. When his regiment was disbanded in 1899, he joined West Virginia’s national guard, or state militia as it was called, and by 1910 had been elevated to the rank of major and given command of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry.

It was the 1912 Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike that first thrust Davis into the center of West Virginia’s labor strife, revealing his nonchalance toward civil liberties. The military commission that had held sway over defendants charged with violating Governor Glasscock’s martial law decrees selected him as its provost marshall. Despite the fact that the civil courts in the martial law district were open, the military commission, sitting in the town of Pratt, in Kanawha County, ruled on offenses ranging from larceny, adultery and disorderly conduct to disobeying sentries and perjury. A nearby freight terminal served as a bullpen to hold prisoners, among whom was Mother Jones. On occasion the commission tried as many as thirty prisoners at a time, dispensing with such formalities as indictments or juries. Davis saw to it that those convicted were hustled off not to the county jail but to the Moundsville State Prison.

With Davis’s active assistance, the commission rode roughshod over the civil courts. When the county circuit court issued an order forbidding enforcement of the commission’s sentences, Major Davis, acting on orders from Governor Hatfield, who had by now succeeded Glasscock, blocked the county sheriff from serving the writ on the national guard officer who headed the commission.

In May of 1913 after a pro-labor newspaper, the Socialist and Labor Star, editorially denounced the “coal barons” and attacked Governor Hatfield for arresting a union lawyer and suppressing the Labor Argus, sister paper to the Star, Davis led a raid on the Star’s offices. Bearing warrants from Hatfield himself, Davis and his posse of Guardsmen and sheriff’s deputies forced their way into the paper’s offices in Huntington, overpowered a guard and wreaked havoc, destroying type and printing equipment. From there Davis and his commandos invaded the editor’s home, seizing correspondence and books and rummaging through his files in a search for the paper’s subscription list. The editor and assistant editor were imprisoned for two weeks, when they were finally released with no charges filed against them. The Star brought suit against Governor Hatfield, Davis and the officers on the raid, charging trespass, unlawful suppression of the paper and conspiracy. The state supreme court, laden with Glasscock appointees, rejected the suit, holding that the governor’s actions could only be reviewed via impeachment proceedings.

Davis resigned from the militia in 1915. But when the United States plunged into the Great War, Davis once again donned a uniform, this time as West Virginia’s adjutant general, with the rank of major and the responsibility of providing security for the state’s factories and transportation lines. Since the national guard had been federalized and shipped out of the state, Davis had only the special deputy police force created to meet the wartime emergency to command. When that force was abolished at war’s end, Davis retained his post as adjutant general. And in September 1919, after the miners’ march on Marmet, it was Davis whom Cornwell appointed to head the investigation into their grievances. He also gave Davis an additional assignment, one that Cornwell had not discussed with the union leaders—to decide who was to blame for the march.

Davis seemed to take the second part of his assignment more seriously than the first. After weeks of hearings producing over 600 pages of testimony, and months of other inquiries, Davis delivered his conclusions, which by this time the union must have expected. As to the union’s “wholesale indictment of conditions in Logan County,” Davis found no foundation for that at all. But he had no difficulty assigning responsibility for the armed march: It was the fault of the UMW for issuing a letter based on unfounded information that inflamed the miners.

A few months later in the summer of 1920, when Federal troops were dispatched to Mingo County, Davis returned to action. This time he served as Cornwell’s liaison with Colonel Burkhardt, the commander of the troops from Camp Sherman, with whom he traveled through the county, laying out a plan for assignments of the soldiers.

The new declaration of martial law following the Three Days’ Battle returned Davis to prominence, and he did not delay in making his presence felt. On May 20, the day after martial law was declared, Davis arrived in Williamson, met with Brockus and Pinson and ordered distribution of the proclamation. The next order of business was to vet the list of volunteers for the vigilance committee. Davis and Brockus selected a committee of seven longtime Williamson residents and instructed them “to cross off those they were not absolutely sure of; that is that they could be relied upon to be issued a rifle and ammunition and go out in the interest of law and order.” Each vigilante was given a Regular Army rifle, shipped down from Charleston, eighty rounds of ammunition, a badge and a striped armed band. All told some 780 men gained appointment as volunteers, more than 200 from Williamson.

Serving without pay, they needed to be ready at a moment’s notice, Brockus warned; four quick blasts of the Williamson fire siren, repeated three times, would call them to action.

Conspicuous by their absence from the ranks of the vigilantes were union members, farmers or blacks. In explanation Brockus claimed that he recruited only men who lived close by so they would be ready to respond to any outbreak of violence in the city. “Now it is out of reason to expect to go out there in the country and get a farmer to repel an attack at Red Jacket, for instance,” he said.

In implementing the martial law regulations, it was Davis who decided what was a crime and how it would be punished, without the nuisance of warrants or hearings. In his approach to law enforcement, the Emperor of the Tug appeared to pick up where he had left off during the Paint Creek–Cabin Creek strike. While the rules laid down by Morgan sounded strict on their face, their severity seemed to depend on whether or not a union man was the perpetrator. For example, all union meetings were banned; in fact if as many as three strikers gathered in one place, they were told to move along. Meanwhile the Salvation Army and the American Legion and similar organizations conducted their assemblages and ceremonies as usual.

On the second day of martial law, May 20, Davis banned distribution of the West Virginia Federationist, the state AFL’s newspaper, for an article blaming Morgan, county officials and coal operators for the Three Days’ Battle, and several strikers were arrested for reading the United Mine Workers Journal. The next night Davis and Brockus led a raid at UMW headquarters in Williamson’s River View Hotel and arrested a dozen men, who were in the process of doing nothing more menacing than arranging relief payments to strikers, and carted them off to jail, in some cases for six days.

The broad sweep of the martial law rules, as interpreted by Davis and his minions, inevitably led to a legal challenge. On the afternoon of May 23 Brockus led a detail to an ice cream parlor near union headquarters in the River View Hotel, where they arrested A. D. Lavinder, a UMW organizer, on the charge of carrying a pistol. Lavinder claimed he had a permit for the gun, but the police insisted that under the martial law edict, all such permits were null and void. They told Lavinder he needed to go with them to Davis’s headquarters.

Lavinder, a feisty sort, was not impressed. “If the adjutant general wants to see me, he can come to union headquarters,” he said. Whereupon the troopers hustled him off to jail, and his appearance when he arrived there made it clear that on his way over his captors had found physical expression for their displeasure with his behavior. Furious at this abuse, UMW lawyers filed a petition for habeas corpus on Lavinder’s behalf against the sheriff of McDowell County, in whose jail Lavinder was held because of overcrowding of the Mingo County jail.

While that legal controversy simmered, tension mounted in Mingo. On May 24 Sid Hatfield arrived in the county seat of Williamson to answer charges growing out of his fracas with the mine superintendent in Matewan in the midst of the Three Days’ Battle. On hand to meet him were Brockus, Davis and a contingent of armed vigilantes. But Hatfield got off the train on the wrong side, eluded his hostile reception committee and received a hero’s welcome from a multitude of admirers as he marched down the street to the courthouse.

Meanwhile, with much less fanfare, a shipment of Thompson submachine guns arrived in Mingo County and were distributed to state police. Nearly every day now, union miners were being arrested for carrying union literature, for speaking against martial law and for carrying arms. Held without bail or hearing, they overflowed the Mingo jail. Brockus had to send them, like Lavinder, to prisons in adjoining counties.

These conditions in West Virginia were drawing increasing attention outside the state, creating an opportunity for labor leaders and their liberal allies to renew their demands for a Senate inquiry. This time they chose to target a figure well known for his willingness to defy the Republican establishment that ruled the world’s most exclusive club, Senator Hiram Johnson of California. Hard-driving, humorless and often ham-fisted in his approach to issues, Johnson’s fealty to conscience and principle was unquestioned even by his foes. He had established that reputation early in his career as an assistant district attorney in San Francisco. When a colleague prosecuting corruption charges against a leading political grafter was shot down in open court, without blinking Johnson took over the case and gained a conviction.

In 1912 he risked his political future by breaking with the GOP regulars to run as Theodore Roosevelt’s vice presidential candidate on the Bull Moose ticket. After six reform-filled years as governor of California, he had come to the Senate in 1916, where his integrity remained remarkably intact. In him the labor leaders found what they needed, sympathy for their cause, a willingness to act and a powerful voice. On May 24, as the West Virginia state police were taking inventory of their newly arrived submachine guns, Johnson introduced a resolution calling for an investigation of violence in the coalfields of southern West Virginia.

The next day, in West Virginia, disorder claimed more lives. Snipers from one of the strikers’ tent colonies lodged themselves in the Kentucky hills and fired into the Big Splint colliery, between Borderland and Nolan. A state police detachment arrived on the scene, together with Kentucky guardsmen, and came under fire. One trooper and one guardsman were killed, and one of the snipers was mortally wounded. Two men were arrested and another escaped into the hills. Brockus sent a posse after the escapee, who was brought back to West Virginia without benefit of extradition. “We do not know the state lines down there and we don’t care,” one trooper told the New York Times. “The prisoner was lucky to get into the lockup alive.”

The outbreak at Big Splint drew increasing attention to the tent colonies of strikers, particularly the settlement at Lick Creek, which was by far the largest. A New York Times story out of Williamson datelined May 26, the day after the Big Splint violence, reflected the attitude of Davis and his cohorts toward the strikers and their families. The story pointed out that the violence at Big Splint occurred only a short distance from Lick Creek. “The question of what to do with these colonies, now regarded as perhaps the chief obstacles in the maintenance of peace in the Mingo coal fields is one of the most difficult confronting the authorities,” the story added. “The colonies are presently free from close surveillance that many persons think they should be subjected to. The Lick Creek and Nolan colonies are on the shore of the Tug, making escape into Kentucky for tent dwellers a comparatively easy step.” Though the story was sparing in quoting officials by name, given the views expressed, it was not hard to identify the “authorities” and “many persons” expressing concern about the tent colonies as Major Davis and his aides.

Meanwhile, Davis left his command post at Williamson to go to the state capital to meet with Morgan and other state officials about the problem of the tent colonies and about handling the dozen or so cases stemming from martial law arrests. Not surprisingly, Harry Olmstead, spokesman for Williamson Operators, accompanied Davis and participated in all the meetings. Actually with Davis on hand, Olmstead’s side was already well represented. The adjutant general let it be known to reporters that the measures put into effect so far were “too gentle,” and that he planned to get the governor to approve “a tightening of the reins by military authorities.”

What Davis had in mind was to create a sort of predecessor of the Gulag. He contemplated expelling the union families from the tent colonies, commandeering their tents and resettling the erstwhile occupants in new camps under military control, at what he considered a safe distance from the strike zone and the refuge of the Kentucky border. Judging from what happened later, it seems probable that a raid on the Lick Creek colony was also on the agenda.

But for the moment, Davis held off any new aggressive move. With the Senate resolution hanging fire on Capitol Hill, he did not want to give forces lobbying for the investigation additional ammunition. Instead he was content to put on a show of strength in the Williamson Memorial Day parade, when state troopers, led by Brockus, marched to the colors. They were joined by a substantial contingent of the American Legion and the newly formed vigilante corps, or Law and Order Committee as its creators preferred to call it.

A few days later, on June 4, Major Wilder, concluding that his 300 Kentucky National Guardsmen were no longer needed, withdrew his force back to Pike County. But that still left Davis in charge of a formidable force—some 800 state troopers, vigilantes and coal company guards, all equipped with weapons, not to mention a fair number of strikebreakers who were carrying weapons for their own defense, a violation of the martial law decrees, which Davis chose not to notice.

In this environment an explosion of new violence seemed only a question of time. The clock began ticking on the morning of June 5, when nervous Lick Creek colonists fired at an auto carrying five passengers whom they took to be hostile vigilantes. Immediately, Brockus and Sheriff Pinson swept down on the colony and arrested about forty miners. There was no resistance, though eight men fled into the woods. Arriving on the scene, Major Davis issued a stern warning: “If there is any more shooting up there you can just line up on the road because we are going out and bring everybody in. You are not going to stay in jail two days either. You will stay longer.”

Given the bellicosity of that visit, when Davis and Brockus returned to Lick Creek nine days later, supposedly to arrest a miner charged in a shooting incident, they could hardly have been surprised at their reception. The suspect they were hunting, standing on the porch of his home, opened fire on their car with a pistol. Then snipers began blasting away from behind rocks and crags on the hills.

Davis was ready for that. He ordered a trooper to rake the hillside with one of his newly issued tommy guns. The trooper was reluctant so Davis repeated the order, with emphasis. This time the trooper obeyed, firing half of the two rounds in his clip. The snipers responded. The trooper emptied the clip at the hills, and the sniping stopped. Then Davis returned to Williamson and sounded the call to battle—four blasts repeated three times on the fire house siren. Within ten minutes about seventy members of the Law and Order Committee responded. Davis loaded them into twenty cars and drove up Sycamore Creek, which parallels Lick Creek. Brockus meanwhile alerted the state police to seal off the only exit roads from the colony. His plan was to herd all the snipers in the hill back into the tent colony and its environs and trap them there.

Starting at the top of the mountain, Brockus and his men formed a skirmish line about a mile long, and proceeded downhill, searching for snipers. As they approached the fence bordering the colony they came under fire. “It was rather hot for a time,” Brockus recalled later. After about fifty to seventy-five shots were fired, Brockus suddenly heard a cry for help. It was one of his troopers, James A. Bowles, who had been dispatched with a party of fifteen vigilantes to sweep the other side of the hill, which Brockus believed to be lightly defended. But Bowles spotted a group of armed miners in a wooded valley to the rear of the tents, just as they noticed him.

Both sides began firing. Bowles shot and killed a miner, Alex Breedlove, in cold blood, according to the miners, and was himself shot through the shoulder, again according to the miners, by one of his own men. A wild scene ensued. An enraged Brockus ordered his men to drive the miners and their families out of the tents, while the Law and Order vigilantes ransacked the tents, slashing the canvas, smashing the furniture and driving the miners and the families to the road. The women and children were released but forty-seven of the men were lined up on the railroad track and marched down the road to Williamson. There they were herded into a single jail cell and held for four days, when eight of them were charged with violating the martial law edict and the rest released.

The uproar caused by the death of Breedlove and the assault on the tents led to a visit to the colony on June 15 by Judge Bailey, who two months before had presided over the Matewan shoot-out trial, an assistant county prosecutor and an attorney for the miners. As they were inspecting the area, a vigilante in a passing car, who mistook the officials for miners, paused to shout: “If you damn red necks haven’t got enough, we will give you more of it.”

Even as Major Davis’s tactics heightened antagonisms on both sides, the state’s efforts to crack down on the miners suffered a legal setback. On June 14, the same day as Brockus’s raid on Lick Creek, the state supreme court, ruling on appeals by A. D. Lavinder, arrested in the ice cream parlor case, held that the martial law proclamation was invalid. Imposition of martial law required the existence of an official military force, such as the National Guard, for its enforcement, the court held. “There was no actual militia organization or force representing the state government in Mingo County,” the court pointed out. Though Major Davis, who held a military commission, was directing the civil authorities, “they were not enrolled, enlisted or organized as a military force.” While the ruling was based on technical grounds, the opinion stated the court’s disapproval in broad terms. The governor could not “by a mere order convert civil officers into an army and clothe them with military powers . . . set aside the civil laws and rules by his practically unrestrained will,” the court said. Using reasoning that must have stunned Davis because of its contrast with the Labor Star decision by the same court a decade earlier, the justices declared: “Power in a chief magistrate to effect such result would be suggestive of the despotism of unrestricted monarchial government . . . preclusion of which is one of the chief aims . . . of constitutional popular government.”

That left Morgan in a lurch, and in dire need of a military force the court would recognize as legitimate. West Virginia’s legislature had finally gotten around to reestablishing the National Guard, but those units would not take the field until late July. In the meantime the governor made use of an all-but-forgotten statute to set up a temporary militia that would meet the requirements of the state court’s ruling.

On June 27, two weeks after the court handed down its ruling in the Lavinder case, Morgan issued an order supplementing his martial law proclamation, directing the sheriff of Mingo County to create an “enrolled militia” of 130 men, drawn from all county residents. Until the National Guard was activated these units would enforce the martial law edict. Meanwhile the vigilante force would be disbanded, though many of its members would serve in the temporary militia, which also would be commanded by Major Davis. Given the make-shift nature of this enrolled militia, the court’s ruling weakened Morgan’s hand at least temporarily. More significantly, it also raised further questions outside the state, particularly in Washington, about the credibility of his governance.

Ever since Hiram Johnson had introduced his resolution calling for a Senate probe of West Virginia’s labor unrest, he and the UMW’s friends in the nation’s capital had been monitoring the state looking for fresh ammunition. Brockus’s ill-fated raid on Lick Creek combined with the supreme court’s overturning of martial law and its rebuke of Morgan gave them what they wanted. On June 21, a week after the Lick Creek raid and the supreme court decision, Johnson rose on the floor of the Senate to demand his colleagues respond to “the existence of a state of civil war” in West Virginia. The day after his resolution had been introduced, he pointed out, there had been more killings in West Virginia. “This never would have occurred,” Johnson contended, if the Senate had acted and appointed an investigating panel earlier. “Do Senators wish to see some of the scenes of the place where this civil war exists?” Johnson asked and referred his colleagues to news photos of the tent colony “showing men and women living simply under God’s canopy in tents and in many cases guards have slashed so as to destroy the only abode that these poor people have.”

Just the previous day, Johnson reminded the Senate, Nebraska Senator George Norris had denounced the tactics of British troops waging guerrilla warfare against Irish Republican militants. Johnson also recalled the stories of alleged atrocities by the Kaiser’s troops against women and children during World War I. Such episodes were more than matched by the accounts of violence against innocent women and children in West Virginia, Johnson claimed. “There never has been in our history, if these stories be accurate, anything like the conditions that obtain today in this territory at our very doors.”

This time the Senate did not delay. Johnson’s resolution was readily adopted and the Senate instructed the chairman of its labor committee, Iowa’s William Kenyon, to do what he had resisted doing a year earlier, “make a thorough and complete investigation of the conditions existing in the coal fields of West Virginia in the territory adjacent to the border of West Virginia and Kentucky . . . and report its findings and conclusions thereon to the Senate.” One year after the shoot-out in Matewan, the struggle between the mine workers and the coal companies was to shift to yet another domain, the time-honored halls of the United States Senate.

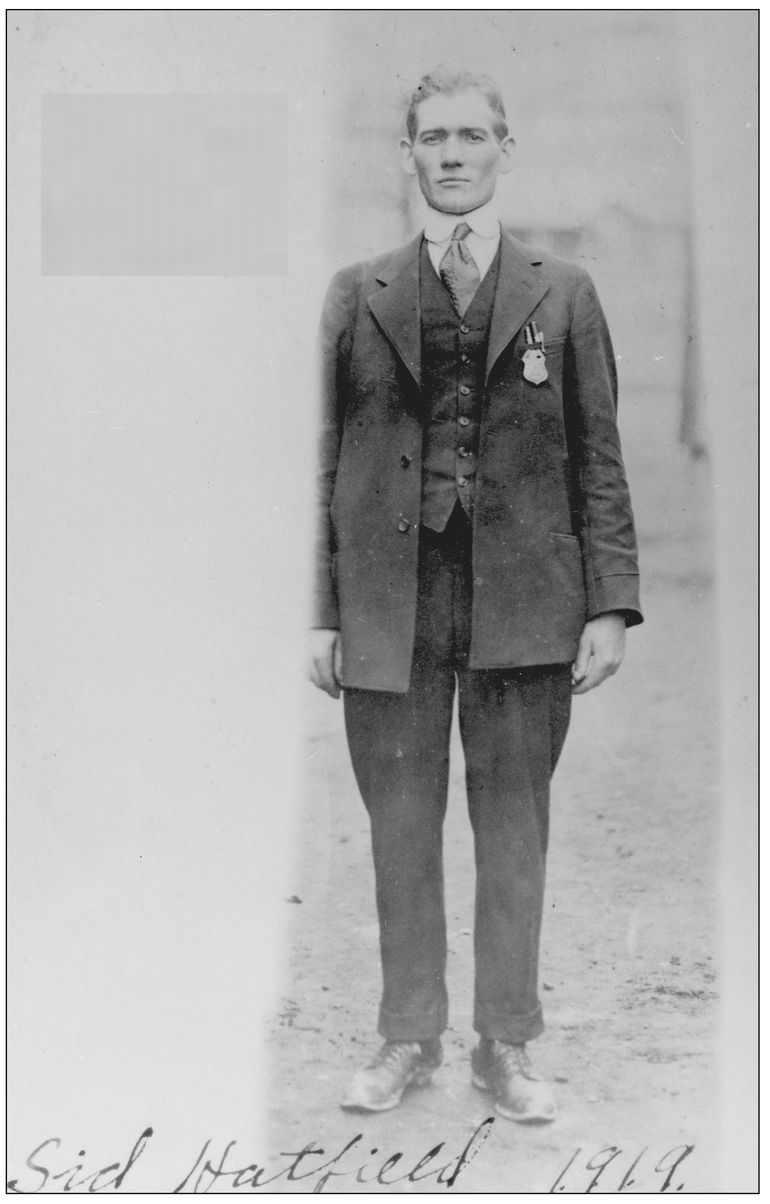

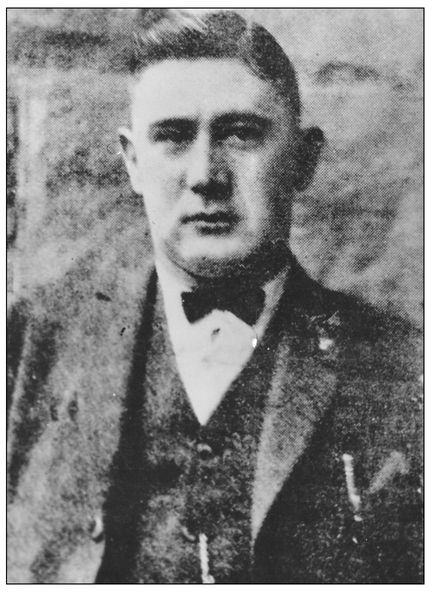

Sid Hatfield: At the center of the storm. Credit: West Virginia University Library/ West Virginia Regional History Collection.

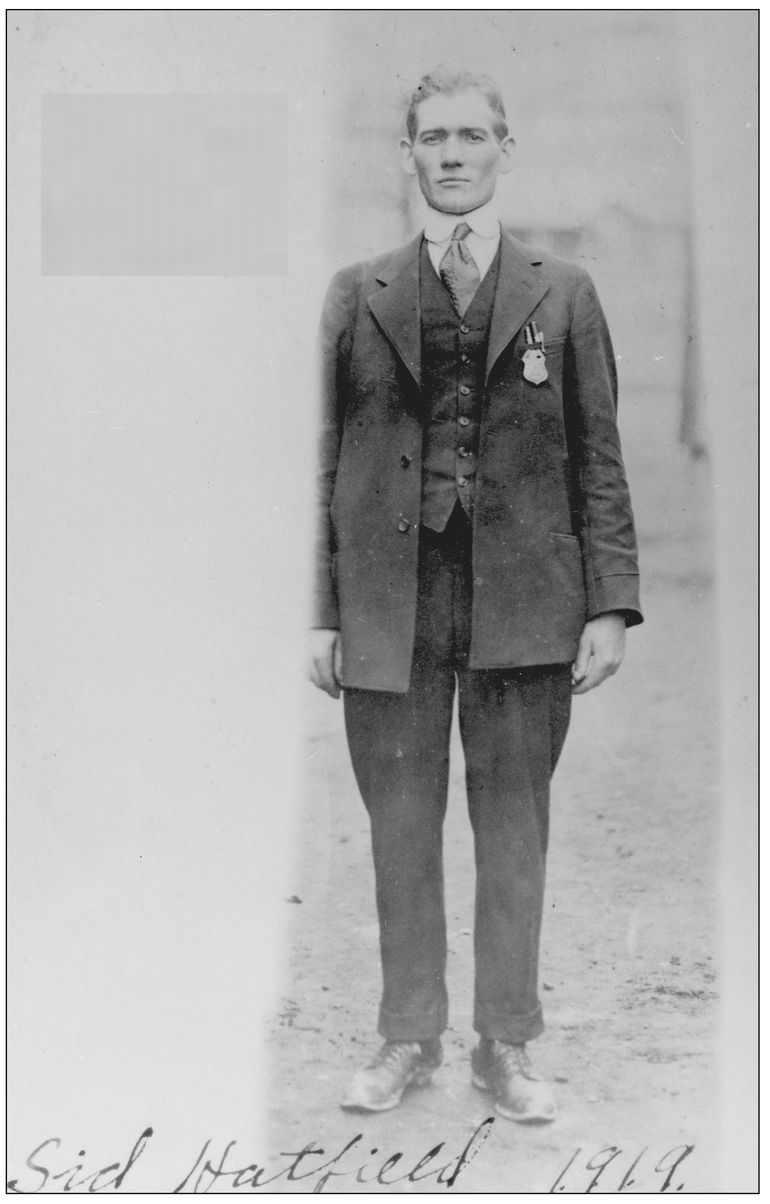

Boss detective Tom Felts: He sought revenge for his slain brothers—and got it. Credit: West Virginia University Library/ West Virginia Regional History Collection.

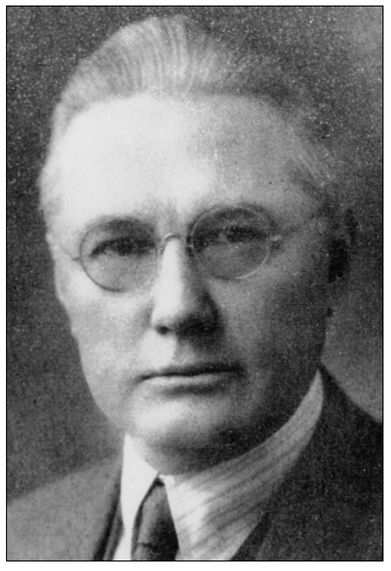

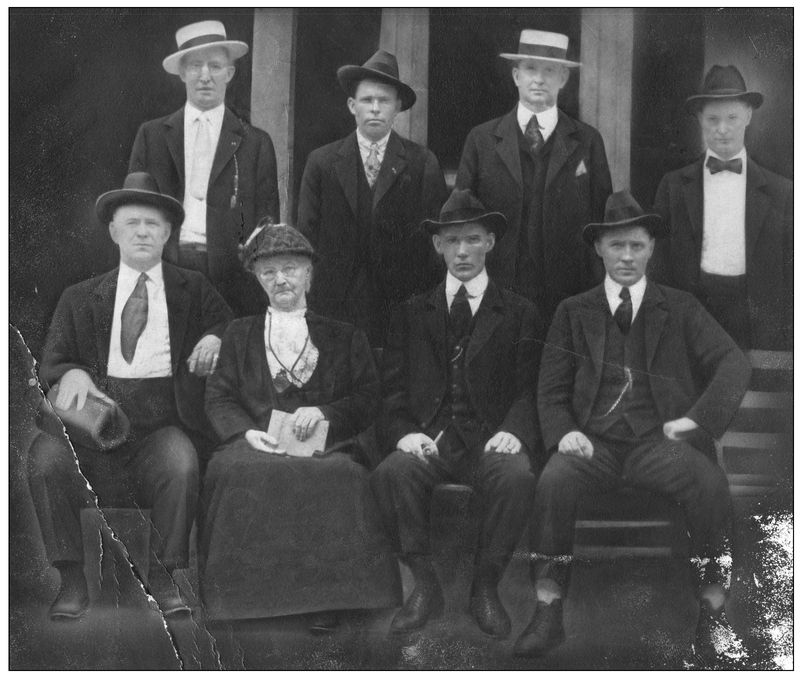

Defendants in the Matewan shoot-out trial: Sid Hatfield is standing 5th from left, Ed Chambers is 3rd from right. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

“The most dangerous woman in America”: Mother Jones with Mingo County organizers in 1920, Sid Hatfield on her left. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection.

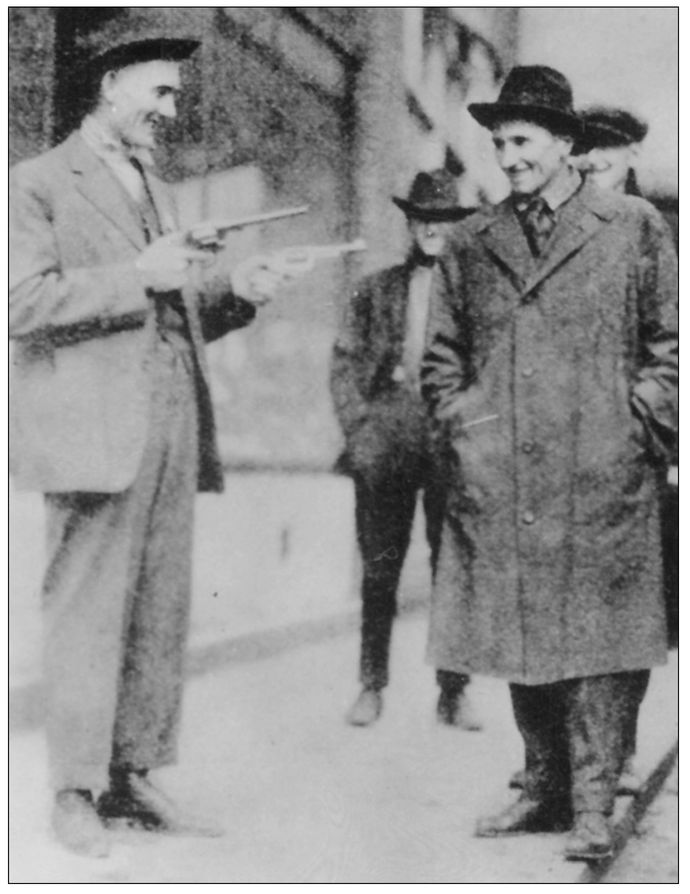

Hatfield’s lighter side: “Smilin’ Sid” clowns for a photographer. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

“It was Uncle Sam that did it”: U.S. troops guard the streets of Matewan. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

Don Chafin: Top Gun in Logan County. Credit: West Virginia University Library/ West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

First line of defense: State police and mine guards manning the trenches on Blair Mountain. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

Ready for trouble: Mingo County’s volunteer militia rallied against the union march. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection. Source: H. B. Lee.

A farewell to arms: After the battle, U.S. soldiers stacked arms and ammunition of both sides. Credit: West Virginia University Library/West Virginia Regional History Collection.