Language: Instrument for the Transmission of Knowledge

The Nature of Language

THE SIMPLEST FORM OF VIBRATION THAT OUR SENSES can perceive is the vibration of air, which, within certain limits, we sense as a sound. We can use sound vibration as a departure point and means of comparison for an understanding of the other, more complex vibratory states—whether they concern the structures of matter or of life, or the phenomena of perception and thought. We have seen that, because of his double nature, man has two roles to play: one concerns the continuation and development of the species; the other concerns the transmission and evolution of knowledge.

There are parallels between the transmission of life and the transmission of knowledge, between the Being of Flesh and the Being of Knowledge. The elements that form the genetic code are, like those which form language, similar and limited in number. They are called the Aksharä(s) (constants).

As far as language is concerned, the Aksharä(s) are the various elements of articulation that the vocal cords can emit and the ear can recognize. There are fifty-four of them. In addition, there are the fifty-four intervals of the musical language that can be distinguished by the ear and that have psychological effects. An analysis of musical intervals will allow the establishment of numerical factors that act as a kind of mathematical key to the diagrams and graphs at the base of the structures of life; it will also give us an insight into the mechanisms of perception, sensation and thought.

The Manifestation of Thought

THE basic instrument for the formulation of knowledge is language, whose limits establish the possibilities for analysis and the transmission of thought.

What is language? How can the variations in articulated sounds be used to define, express, and transmit ideas? Indian grammarians and semanticists tried to define the nature, possibilities, and limits of language, as well as its relationships with the structures of the world and the mechanisms of thought. Thought exists outside language; the various languages are merely collections of signs (sound or otherwise) that are used to delineate thought and transmit its approximate outlines. It is therefore essential that the vocabulary and the structures of language not be confused with ideas. Nevertheless, according to the Hindu grammarians, there must be some relation among thought, perception, and language; without it, language could not act as a vehicle for the others. In this area, as in the others, they have therefore sought out archetypes that are common to the mechanisms of perception and thought, and to the structures of language, music, and the other modes of communication.

An idea is an inner vision that we try to formulate with the help of those symbolic elements which are the words or gestures we use. The crudeness of such a formulation may be greater or lesser, depending on the richness of our vocabulary, but it is always a mere approximation. An idea is not in itself connected to language. We seek words to express it, and often hesitate between different alternatives. An idea first appears in an indivisible form called Sphota. It can be compared to a landscape lit up by a flash of lightning. Some notions, some experiences and sensations, often the deepest and the most violent, remain inexpressible. Mystics cannot describe their experiences. We ourselves cannot communicate the nuances of pleasure or sorrow with any precision. Language can therefore be a barrier. It is, according to the theories of Yogä, necessary to remove the barrier of language and to "reduce the mind's activity to silence" in order to achieve a perception of the suprasensory world.

The idea is born in the substratum of consciousness called Parâ (the Beyond), where it appears as a kind of vision (Pashyantî). Dreams form part of this Pashyantî. In order to transform an idea into an instrument of action or communication, we attempt to define and formulate it mentally, using the symbols of language. This stage is known as Madhyamâ (intermediary). It is clear that such a formulation is approximate, for we have at our disposal only a limited number of tokens or words with which to form its outlines. At length we exteriorize it in a sound form called Vaikharî (exteriorized). These last two stages are particularly developed in mankind, although they vary according to the intellectual capabilities and the vocabulary of individuals. They are extremely rudimentary in animals.

Through the practice of Yogä we perceive the four stages in the manifestation of thought as being localized within four of the main centers of the subtle body, which is the inverse of the physical body. Parâ is situated at the base of the vertebral column; Pashyanti is close to the navel; Madhyamâ is in the area of the heart; and Vaikharî is in the throat. As always with Yogä, brain centers are involved which can only be localized and controlled through the parts of the body, the corresponding nervous centers, which they command. The theory of the Creative Word is based on an analogy between the processes involved in the transformation of thought into word and sound vibration, and the processes of divine thought, which becomes the substance of the world in the shape of energy vibrations. This analogy enables the Yogi to start from the word and work his way backward, thereby reaching, without going outside himself, the birthplace of the manifested, the limits of the "beyond" (Parâ), the "Principle of the Word" (Shabdä Brahman). It is through this experience that we can have an idea of the process by which the universe is exteriorized by Divine Being.

At the beginning, like a wind that is blowing, I cry out the worlds in space," says the Divine Being of the Rig Vedä. Divisible being emanates from the Being which is indivisible Existence-Consciousness-Joy; From Sat (existence) springs forth Energy, which manifests itself in the form of an elementary vibration that can be compared to a primordial sound (nâdä). It is from this vibration that the boundary point (hindu) issues, separating what is manifest from what has not been manifested. [Sharadâtilakä 1.7]

An echo of this concept is to be found in all traditions: "In principium erat Verbum ante omnia facta sunt. .. ."

According to the Sâmkhyä, the universe has developed from elementary formulae that are mathematical in nature, or at least able to be expressed in mathematical or geometric terms (in this case called Yanträ[s]) and which are common to all aspects of creation. There is no difference of nature between the formulae at the base of the structures of the atoms of matter, the movement of the stars, the principles of life, the mechanisms of perception and thought, which are, all of them, parallel and interdependent manifestations of energy, resulting from common patterns. Language, by means of which we exteriorize and materialize thought and describe the apparent world as it is perceived by our senses, must therefore present to us characteristics analogous to those of the process by which the universe develops. A study of the bases of language, its limits and constituents, should provide us with an idea of the nature of the world; by delving back to the sources of language, we should gain an understanding of the process by which thought is transformed into speech and should be able to uncover something of the way in which the Creative Principle that is the divine "Word" is manifested in Creation. The same result can be achieved starting from visual elements, such as the language of gestures, or biochemical elements, which are the formulae of matter and life, since all aspects of the world are based on a limited number of patterns and formulae.

A distinction must be made in all linguistic theories between words and their meanings. In the aspect of Mahat, Universal Consciousness, Shivä is identified with the meaning of words. The word itself, the instrument of sound with which we express meaning, is a form of energy and is therefore part of the realm of Pakriti (matter), regarded as feminine. "Shiva is the meaning; the word is his wife" (Lingä Purânä 3.11.47).

A study of the formation of words and the roots of language reveals that they always start from abstract notions and move toward the concrete; they start from the general and progress toward the particular. In order to understand a word, its root must be studied. The processes involved in the formation of language appear analogous to the processes of creation.

Provision is made for the birth, possibilities, and limits of language in the very structures of the human animal. The five places of articulation that allow the formulation of the means of communication which we call language are no more accidental than the fact that humans possess five senses, five fingers, and five forms of perception, and that five apparent states of matter exist for us. Man only invents that which he is predisposed—but not predestined—to invent. The organ of language precedes the manifestation of language, and not the other way around. It is thus implicitly part of the plan from the outset.

The Mîmânsâ(s) and the Tanträ(s) study the ritual and magical formulae, that is, the use of language as a means of communication between different states of being. The Vyâkaranä, moreover, studies the structures, the limits, and the contents of language. Its application to Sanskrit is but one example among many. The study of the symbolic meaning of the phonemes, whose use is to be found in Manträ(s), the formulae used to evoke the various aspects of the supranatural world, belong not to the Sanskrit language, but to a general theory of the symbolism of sounds.

The error of wanting to reduce a study of the symbolic bases of language to the elements of a particular language considered to be sacred has often turned the approach to this problem off course, as has sometimes been the case with regard to the Greek, Hebrew, or Arabic alphabets, or for Sanskrit itself.

Texts

THREE are many texts about Creation, conceived as the manifestation of the Principle of the Word (the Shabdä Brahman) and also about the transmission by sound of concepts and the semantic contents of the musical or articulated sound. These texts also study the manifestation of thought through the intermediary of the word, and the parallels that this manifestation can provide with the birth of the world viewed as an apparent materialization of the thought of its creator. Among the most important surviving works on the subject are the Vedic Pratishâkhyä(s), the Kâshikâ, and the Rudrä Damaru of Nandikeshvarä (prior to Pânini), Pânini's Ashtâdhyayi (fourth century B.C.) and its major Commentary, Patañjali's Mahâbhâsyä (second century B.C.), and Kalâpa's Vyâkaranä (first century). To these must be added the ancient Shaiva grammars, of which the one by Râvanä is legendary, and to which Bhartrihari refers in his Vâkyapadîyä (seventh century A. D.). This matter is also treated in several Upanishad(s) and treatises on Yogä.

For this study on the nature of language, I have relied on a long article by Swâmî Karpâtrî, published in the Hindi language journal Siddhantä with the title "Shabdä aur arthä" (Words and Their Meaning).

In mythology the origins of the theory of language is attributed to Shanmukhä, the son of Shivä, and the pre-Aryan Dionysos.

The invocations with which the Vâkyapadiyä (Bhartrihari's great treatise on the nature of language) begins appeal to the goddess of the mountains (Pârvatî), to the eternal Shivä (Sadâshivä), to Shivä as the god of the South (Dakshinamûrti); they refer to the Tanträ(s), the Âgamä(s), and to the ancient Shaiva grammar by Râvanä. There is no mention of the Vedä or the Vedic gods. Bhartrihari also makes reference to the Jaïnä tradition, the other great current of protohistoric thought in India.

We have already seen with respect to the Tanmâträ(s) that a form of communication exists which corresponds to each state of matter or element. Thus there is a language of smell (the element of earth), a language of taste (the element of water), and a language of touch (the element of air). (The tactile language is extremely rudimentary in mankind. A shaking of hands, the pressure of feet under the table, not to mention the caresses of love, are all part of the language of touch.) There is also a language of sight (the element of fire), which is used by man in gesture, mime, and ideograms.

The language of sound, corresponding to ether, is divided into a musical language and an articulated language. The musical language is based on the numerical relationships of frequencies and on the rhythmic division of time. Spoken language is formed from articulated sounds, to which certain tonal elements of music are added. The various forms of language can combine with each other. Gesture, mime, intonation, and rhythm work in combination with the word and allow the expression of what words alone cannot transmit. All living beings have a language; yet it would seem that man is the only one in possession of an elaborate language, even though some animals have a significant number of "words" or "signs." The Shatapathä Brâhmanä (4.1.3.17) says: "Only one quarter of language is articulated and used by men. Of the remainder, which is inarticulate, one quarter is used by mammals, one quarter by the birds, and one quarter by reptiles."

These languages use various means of transmission, which are not necessarily perceived by us. It is sometimes a question of ultrasonic transmission or along the lines of radio or radar, permitting direct intuitive communication (the reading of thoughts, etc.). Gesture, mime, and the emission of certain waves play an important part in the language of animals, insects, and even plants, although with plants, for which time has a different value, the slowness of movement makes changes imperceptible to us. In the same way, bird language, which is too fast for us, appears to us like a recording played at the wrong speed. Insects communicate over very long distances by means of extremely delicate odors.

Man finds that some sounds have a direct relationship with some emotions, but on the whole we tend to believe that the use of phonemes to represent ideas is conventional. This raises a fundamental question. For the Indian grammarians, sounds must have originally a meaning and a logic of their own. This is what allows them to be the image of material or abstract realities. It was the grammarians' belief that language was originally entirely monosyllabic and tonal. By this theory, Chinese is closer to the primitive languages than the Semitic, Aryan, or Dravidian languages. A monosyllabic language functions by the juxtaposition of substantive elements (nâmä), elements of form (rupä), and elements of action (kriyâ), and therefore lends itself to a parallel representation by means of graphic symbols, ideograms or by gestures (mudrä).

The phonemes, which originally have a precise meaning (indeed a natural meaning), form the material from which the basic roots of language are formed; these roots will combine to constitute words whose meaning is a combination of the constituent parts. It would seem that in no language can any new roots ever be invented. These could, in any case, be nothing but a transposition or displacement of the original meaning, since there can be no new elements of articulation. In order to define ideas, all languages therefore use the fifty-four possible articulated sounds. This is very limited material, which means that words can only be approximations allowing a vague outline of the thought they express.

The organ of speech is constituted as a Yanträ, a symbolic diagram. The palatal vault (like the celestial vault) forms a hemisphere with five points of articulation allowing the emission of five groups of consonants, five main vowels, two mixed vowels, and two secondary vowels, assimilated to the planets.

Likewise in the musical scale, there are five main notes, two secondary ones, and two alternative notes, which are not arbitrary but correspond to fundamental numerical relationships between the sound vibrations that we can find at the base of all musical systems. Our perception of colors has analogous characteristics. We cannot in any case invent new vowels, new places of articulation, or new fundamental colors. The possibilities of our vocal organ and the powers of discrimination of our perception are severely limited, coordinated, and preestablished according to criteria to be found in all aspects of creation.

The Maheshvarä Sûträ

THE material of language (that is, the set of articulated sounds that will permit the definition and transmission of thought) is classified in a mysterious formula that is considered to be the source and summation of all language. This formula is known as the Maheshvarä Sûträ and is symbolically described as issuing from the Damaru, the god Shivä's little drum, whose rhythm accompanies the dance by which he gives birth to a world which "is nothing but movement" (jagat). The Maheshvarä Sûträ attempts to establish the relative significance of the phonemes, the basic sound-tokens that form the material of language, and their relationship with the fundamental laws that rule the material, subtle, and transcendent worlds.

The analysis provided here of the Maheshvarä Sûträ is based upon the two short treatises attributed to Nandikeshvarä and the commentaries on them. Nandikeshvarä attributes a basic meaning to the various linguistic elements according to the placement and movements of the vocal organs that produce the different sounds of the spoken language. The commentators explain how the sounds produced by the various efforts of the vocal organs can be used to materialize concepts, and how such inflections, which can seem to be minimal even on the microcosmic scale, can, when multiplied to the scale of the universal being, reflect prodigious energies.

Already in mankind the power of language is out of all proportion to the minimal movements of the throat and lips that produce the sounds.

The use of a few vowels and consonants which did not originally exist in Sanskrit seems to indicate that Sanskrit is not at the base of the phonetic system even though it became closely linked with it. The phonetic system is independent of the diversity of languages and of the various systems of writing, through phonemes or ideograms. Alphabets differ only in their imprecision and their deficiencies. The twenty or so alphabets used in India are for the most part merely different ways of transcribing the same phonetic system. The Semitic alphabets (Aramaic, Hebrew, Arabic), as well as the Phoenician and Greco-Roman alphabets, are particularly deficient, being very imprecise. The alphabet of classical Sanskrit, called Devânagarî, is by far the most suitable for the transcription of the fifty-four elements of articulation at the base of all languages. The limits of the possibilities of language are tied to the limits of our possibilities for collective and transmittable knowledge, that is, to the role that has devolved upon the human species as a whole in the play of creation. We can only surpass these limits if we are able to pass the limits of language and of the mental mechanisms to which it is tied; such experiments are, however, difficult to communicate.

The seeds of all human knowledge, the sciences and all that language can contain and express, can be derived from the Maheshvarä Sûträ, which means "Sacred Formula of the Great God." The Maheshvarä Sûträ is as follows:

A-I-U-N; Ë-Ü-K; É-Ó-Ñ; È-Ò-CH; Ha-Ya-Va-Ra-T; La-N; Na-Ma-Na-Na-Na-M; Jha-Bha-Ñ; Gha-Dha-Dha-Sh; Ja-BaGa-Ga-Da-Sh; Kha-Pha-Cha-Tha-Tha-Chha-Ta-Ta-V; Ka-Pa-Y; Sha-Sha-Sa-R; Ha-L.

U is pronounced like ou in you; I like the i in bit; Ë and Ü like the French e and u; CH like tch; J as in dj (z is considered to be a variant of j). The cerebrals, indicated by underlining, are obtained by touching the palate with the tip of the tongue. Ñ is guttural. Sh is pronounced like the French ch, Ñ as in Spanish. The half consonants at the end of each group are called "it". Their meaning refers to the whole of the group that they bring to a close. They allow the sets of groups to be established. A–Ch represents the group of vowels.

According to Nandikeshvarä's interpretation, the groups of letters represent, following a given order and hierarchy, the sound symbols that allow the transmission of concepts, starting from the most abstract, just as the series of numbers and their relationships can be the basis for a mathematical expression of the manifestation of the elementary principles that make up the substance of the world. These two series form the base of the sciences and all forms of knowledge. The Maheshvarä Sûträ attempts to bring out the relationship between the sounds and the meanings of the various basic elements of language. The roots as well as the grammatical structures of all languages can, in principle, be derived from these data. Pânini provides an explanation of this relationship for the Sanskrit language, but it would be possible to analyze the structures of any other language using the same method. What is important is to establish the connection between sounds and fundamental notions, allowing one to express the other, which is the primary problem of language. The structures of language, formed from elementary meaningful units, appear parallel to those of the elementary cells that give birth to matter and life.

The Nine Vowels

A-I-U-N

A represents Purushä, Universal Man, the plan, the first stage in the manifestation of the world. In the first group, A-I-U-N, the first letter, A (pronounced as in father), is the least articulated sound. It is produced when all the organs of articulation are at rest. All the other sounds are but its modifications. "The totality of speech is contained within the A," says the Aitareyä Âranyakä; while the god of the Bhagavat Gîtâ also declares: "I am the A among letters." "This is why A, the first of the letters, represents the form (rûpä) which the undifferentiated, unqualified, informal principle, the Nirgunä Brahman, takes on when he creates the world. Omnipresent throughout his work, he is the universal ego (Aham) in which the beginning and end are united" (Nandikeshvarä Kâshikâ 3–4). The notion of individual person, whether divine or human, exists only within the limits of the apparent world. A is thus the symbol of the first stage of existence, of the passage from a nonexistent, indivisible, and impersonal absolute to a totality of personified existence, represented as the Universal Man, Purushä, whose form is the universe.

I evokes Shakti, the energy and substance of the world. "I represents the conscious part (cit kalâ) of organized matter" (Nandikeshvarä Kâshikâ 3). It is the closest vowel to A, and to produce it, it is necessary only to add an intention or a tendency toward the exterior without moving the lips. Nandikeshvarä explains that "when, in the undifferentiated Principle, the desire to create a world which does not yet exist appears, this corresponds to an I. I (pronounced as in bit) is termed the 'seed of desire' (kâmä-bîjä)" (Kâshikâ 8). "Without the I, which represents his energy, the eternal Shiva remains as inanimate as a corpse (shavä). It is only when united with his energy that he can act. From man's point of view, the letter A represents the object of knowledge, while I is the instrument of knowledge—consciousness (cit)" (Kâshikâ, 9).

U (pronounced as in rule) represents the accomplished plan, the materialized desire—that is, the universe. If our organs of articulation combine the positions for A and I, and the result is exteriorized through the lips, the sound U is obtained. U is A + I exteriorized, that is, the plan exteriorized in matter. "U represents the sovereign principle (Ishvarä) of which the universe is the expression" (Kâshikâ 3). For the Sâmkhyä, the sovereign principle is Universal Consciousness (Mahat). "U represents the consciousness (Mahat) which is present in all things and which we call Vishnu, the Omnipresent" (Kâshikâ 9). The first group of letters in the Maheshvarä Sûträ thus evokes the eternal Trinity of the ideating principle, the active principle, and their result, the manifested principle (the world). The sounds that are the symbols of these three principles constitute the roots which, in the primordial language, evoke these notions. This is why, in all languages, the sound A expresses the void, the nonexistent, the nonmanifest, and is therefore negative, privative, and passive. It is predominant in the words that represent these ideas, whereas the sound of I is an indication of action. I predominates in words expressing life, activity, desire, etc. "The letter A, by making vibration perceptible, is the image of the creative principle of the world. I, representing Shakti, suggests the energy which is at the origin of [all the aspects of the apparent world represented by] the other letters" (Kâshikâ 7). We shall see that the causal aspect of the I influences the classification on the consonants. U represents localization, the apparent world.

A is pronounced with the throat, I with the palate, U with the lips. The two vowels of the following group are pronounced in the intermediate spaces corresponding to a cerebral and a dental. The cerebral Ë corresponds to the French e, according to its definition by the ancient grammarians. Modern Indians, who cannot pronounce it precisely, call it ri which is clearly wrong since a vowel is defined as a prolonged, sustained sound.

The following vowel is a dental Ü, corresponding to the French u. It is pronounced as lri by modern Indians because I is the consonant pronounced at the same place. These vowels are still used in some Indian languages. In these cases one refers to the god Keushnä rather than Krishnä.

"Ë and Ü symbolize movement, the activity (vrittä) of thought, an activity which can be compared to that with which the Divine Being engenders through his power of illusion a universe which is pure movement" (Kâshikâ 10).

In the order of manifestation Ë (ri) represents the first and absolute reality (ëtä or ritä), which is to say the Creative Principle, the Sovereign God personified (Parameshvarä).

Ü (lri) represents Mâyâ, the power of illusion by which the universe seems to exist. Ë and Ü thus correspond on the manifest plane to what A and I evoke on the plane of the preexistent. The Sovereign God, by means of his powers of illusion, makes the world appear. Yet the Divine Being cannot be separated from his power of action. This is why

Ë and Ü are not truly distinct from one another. There is no real difference between the tendency itself and the one in whom that tendency exists; the relationship is the same as that between the moon and its light, or between a word and the meaning it expresses. [Kâshikâ 11]

It is through his own "power to conceive" (cit) it that the Sovereign God is able to make the world appear at his whim (God and the world are neither opposite nor complementary principles). Existence is not truly separate from the Being which it reflects; yet a reflection does not have the ability to act autonomously. This is why the verbal symbols Ë and Ü are termed impotent, neutral, or androgynous (klïbä). [Kâshikâ 12]

All creatures issue from an androgynous principle, which is subsequently divided, only in appearance.

The fifth vowel is the last of the pure vowels, for we have only five distinct places of articulation. The obstruction or explosion of the vowels in these very five places constitutes the five groups of consonants: the gutturals, the palatals, the cerebrals, the dentals, and the labials.

É-Ó-Ñ

The two vowels of this group are hybrids and not consequential ones like U. They are A + I = É and A + U = Ó.

É represents the nonmanifested principle (A) when it is combined with its energy (I). A is the immovable and indestructible principle (aksharä). I is illusion, active intelligence, stemmjng from indivisible, inactive intelligence. "In E [that is, A in I] the motionless principle becomes identified with its energy; the nonmanifest is present in its powers of action. We meet this fundamental identity of the creative principle and its powers of illusion in everything that exists" (Kâshikâ 13).

Ó represents the principle A present in its work U. "Having created the universe, he resides in it." O (A in U), the vowel from which the syllable of adoration, AUM, is formed, represents the unity of macrocosm and microcosm, of the divine being and the living being; the iconographic form of this symbol is the god Ganeshä, who is both man and elephant. Ó thus declares the "unity of opposites" (nirâsä) and reminds us that the total and the individual, the Sovereign Principle (Ishvarä) and his power of illusion (Mâyâ), are one. It is the Sovereign Principle which is consciousness (Mahat), which "like a witness or spectator is the principle of unity present in the [multiplicity] of beings and elements (bhûta[s])" (Kâshikâ 13).

È-Ò-CH

This group presents open vowels which are almost diphthongs (AÉ, AÓ) and which comprise three elements: A + É = È, and A + Ó= Ò. Eis formed by adding a new A in front of E, which is already A + I. È is the retroactive effect of E (the power of manifestation) on A (the nonmanifest principle). E is therefore an image of the relationship between the Supreme Being and the universe contained within him. It is the nonmanifest principle marked by its power of illusion.

In the same way, Ò, which is A + Ó—that is, A + (A + U)—represents the nonmanifest principle in which the manifest world exists like an embryo within the womb. "The world is but an apparent form stemming from a formless principle in which it resides and which develops it or reabsorbs it as it chooses" (Kâshikâ 14).

This completes the series of vowels, which thus comprises nine sounds (seven principal and two subsidiary), like the musical scale but also like the astral molecule which forms the solar system. The musical scale is also based on frequency relationships, which can be expressed in numbers. There are thus arithmetic parallels to the sounds of language; these are also to be found in the geometric diagrams (Yanträ[s]) which are at the base of the structures of matter and the principles of life.

Various elements, when added to the pronunciation of vowels, modify their meaning and allow the expression of multiple concepts. Each of the vowels can in effect be pronounced eighteen different ways, which are differentiated by the pitch of the sound (by raising or lowering the voice of a tone, or by keeping it level), or by its duration (short, long, or prolonged), or finally by exteriorizing or interiorizing it, that is, by making it natural or nasal. (We express a question by raising the voice on, for example, the word "Yes," and express assent by lowering the sound of the same syllable).

All these details are indicated in the system of writing used by the Indian grammarians, thus forming a total of 162 distinct vowel sounds. In a classical example, a mistake in accentuation in a magic rite of the incantation "Indrä shatruh" changed its meaning from "Indra the enemy" to "the enemy of Indra," and the utterer of the rite provoked his own destruction.

The Consonants

CONSONANTS are obstructions placed in the path of the utterance of vowels. Their differences depend upon the place of articulation together with the nature of the explosion and the effort, which can be directed either inwardly or outwardly. There are four categories of inner-directed effort: a strong touch, a light touch, open, or contracted. There are eleven sorts of outer-directed effort: expansion, contraction, and breath, to which are added (for syllables formed of a consonant and a vowel) the volume of the sound, its resonance or nonresonance, light aspiration or strong aspiration, and the tone, which can be high, low, or medium.

The Five Groups (Vargä)

THE various efforts to throw out, interrupt, or modify the vowel sounds in the five places of articulation form the consonants. These are grouped, like the vowels, into gutturals, palatals, cerebrals, dentals, and labials. In each place of articulation there exists an outward effort (K, C [tch], T, T, P) and an inward effort (hard G), J (dj), D, D, F, etc.). Both can be either voiceless or aspirated.

The basic consonants are twelve in number: the gutturals K and G (hard); the palatals C (tch) and] (dj); the cerebrals T and D; the dentals T and D; the labials P and F; the fricative Sh (the French ch); and the semivowel L.

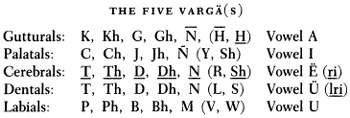

Mixed with the aspirates or in combination, these twelve types of consonants produce thirty-three distinct articulations. Their meaning is determined by the meaning of the vowels, the place from which they are articulated, combined with the effort of articulation. The complete alphabet comprises five groups of consonants, called Vargä(s):

- Five gutturals: K, Kh, G (hard), Gh, and

(guttural-nasal); and also a guttural fricative H (as in Arabic) and an exhaled final H (Visarga).

(guttural-nasal); and also a guttural fricative H (as in Arabic) and an exhaled final H (Visarga). - Five palatals: C (tch), Chh, J, Jh, and Ñ (nasal-palatal); and also a semivowel Y and a fricative Sh (French ch).

- Five cerebrals (where the point of the tongue touches the palate): T, Th, D, Dh, and N (nasal-cerebral); and also the semivowel R and the fricative Sh

- Five dentals: T, Th, D, Dh, N (dental-nasal); and also the semivowel L and the sibillant S.

- Five labials: P, Ph, B, Bh, M; and the semivowel V and an exhaled final W (Upadmaniyä).

There are thus five groups, each comprising seven consonants (five principal and two supplementary). Two exhalations, the final Visargä and Upadmaniyä, must be kept aside, since they cannot exist in the middle of words. This leaves thirty-three consonants, which, combined with the vowels, form, with very slight variations in pronunciation, the roots and further the words of all languages.

In the Maheshvarä Sûträ, the consonants are not presented in alphabetical order. We meet first of all the semivowels, followed by the nasals, which are the fifth letter in each group of consonants. Only then follow the fourth, third, second, and finally the first letter of each group. We shall see how Nandikeshvarä and his commentators explain this order.

In the logic of creation, once the elements and the "spheres of perception" are defined, we arrive at perception and the individual consciousness on which all perception rests. It is perception which, because of its very limitations, gives the world an apparent reality.

The Tattvä

THE Tattvä(s), all that which in the constituent elements of the world can be called "something" (tat), will find their expression, the means of pointing them out, in the constituent elements of language.

HA-YA-VA-RA-T AND LA-N: THE ELEMENTS (BHÜTÄ)

Following the vowels in the Maheshvarä Sûträ comes the semivowels, or slightly touched (îshsprishtä) consonants, in the production of which the tongue comes close to the places of articulation but barely touches them. They are merely lightly articulated modifications of the corresponding vowels. They indicate the spheres of manifestation of the principles that the vowels represent; they correspond, in the order of appearance, to the five elements or degrees of manifestation of matter which are the spheres of perception of the five senses.

The first four elements are considered to be part of the plan (Purushä, the male principle); the fifth, the solid or earth element, stemming from Prakriti, is considered to be feminine. "The five elements (bhûtä[s]) stem from the Sovereign Principle (Maheshvarä). Ether, air, water, and fire are known as Ha, Ya, Va, and Ra. In the creation by the Word (vâk), H is the name of ether, air is called Y, R is fire, and V is water" (Kâshikâ 15–16).

First among the semivowels appears the guttural H, deriving from A, the formless, undifferentiated principle. H corresponds to the element ether, whose properties are space and time. The first stage in the manifestation is the creation of space and its corollary, time. Once the universe is reabsorbed, space and time cease to exist. Ether is the primordial element on which depends the possibility (avakâshä) for the manifestation of the other elements, which are vibratory modulations of it, in the same way that all articulated sounds are modifications of the nonparticularized sound A.

The palatal Y, which derives from I, introduces the first form for the organization of matter; the gaseous state of air.

The labial V, deriving from U, corresponds to the liquid state of water. The cerebral R, from Ë(ri), corresponds to the state of fire.

LA-N

Lastly, the solid state of matter, called earth, supports the other elements. This solid element corresponds to the dental L, (from Ü, lri), and hence to Mâyâ identified with the Earth goddess and the feminine principle (Prakriti). "Earth is the basic element: it supports the others. It is the earth which provides food; from food comes the seed, and from the seed comes life" (Kârikâ 17).

ÑA-MA-NA-NA-NA-M (NASALS): THE SENSES OF PERCEPTION

The successive states of the condensation of energy, which appear to us as gaseous incandescent, liquid, or solid, are all formed from tiny (sukshmä) entities, or atoms (anu). They resemble dispersed solar systems but are in fact no more than gravitational formations of ether. The states of matter are organized along different means of communication and are only differentiated as far as we are concerned by the perceptions we have of them; and our perceptions are linked to the duration of apparent time and to the relative dimension of space. Their appearance results from the limitations of our five senses. There is a hierarchy of the senses, connected to the order in which the different stages in the formation of matter appear. The ears perceive only the characteristic vibratory forms of space or ether; the sense of touch recognizes the gaseous state; the eyes perceive the igneous state; taste recognizes liquid; and the nose recognizes the solid state. These forms of perception are represented, according to Nandikeshvarä, by the five nasals, which are to be found in the same places of articulation as the semivowels. (In practice, three of these nasals do not appear in the French or English alphabet; they can only be represented approximately.)

"The five nasals are connected with the 'perceptible qualities' (gunä[s]): hearing, touch, sight, taste and smell, corresponding to the five states of matter present in all things" (Kâshikâ. 18). Nandikeshvarä reminds us that from the point of view of experience or perceptibility, the world begins from the materialized energetic aspect represented by I and not from the theoretical aspect (A) of the plan. "I, representing energy (Shakti), is thus deemed to be the principle of all the other letters" (Kâshikâ. 7). The nasals thus start with the palatal Ñ, corresponding to an I, in other words, to Prakrtti, the plan realized in substance.

The nasals, which appear as the fifth consonant in each group, are as follows: the guttural-nasal

(now placed in the center), representing hearing (ether); the palatal nasal N (as in Spanish), representing touch (air); the labial nasal M, representing taste (water); the cerebral nasal N, representing sight (fire); and the dental nasal N, representing smell (earth).

(now placed in the center), representing hearing (ether); the palatal nasal N (as in Spanish), representing touch (air); the labial nasal M, representing taste (water); the cerebral nasal N, representing sight (fire); and the dental nasal N, representing smell (earth).

The hierarchy of the senses reflects the hierarchy of the successive appearance of the different elements. Ether or pure vibration is perceived only by hearing or its analogous senses. The others follow in order: the gaseous state of air, perceived by hearing and touch; the state of fire, perceived by sight, touch, and hearing; the liquid state, perceived by sight, touch, hearing, and taste; and finally the solid element of earth, perceived by smell and all the other senses.

JHA-BHA-Ñ AND GHA-DHA-DHA-SH: THE ORGANS OF ACTION

The fourth letter (varnä) of each group (vargä) represents one of the senses of action which allows the formation of the body of the universe (virât) inhabited by consciousness (cit). They are present in all beings but are not perceptible in inanimate matter. [Kâshikâ 19]

Jh and Bh represent the organs of speech and touch. The tongue, organ of speech, corresponds to the element of ether and is represented by the letter Jh. The hand (pânî), the organ of touch which perceives the gaseous element or air, is represented by the letter Bh. [Kâshikâ 19–20]

Gh, Dh, and Dh introduce forms of action which correspond to the elements of fire, water, and earth and which are present in all living beings in the feet, the anus, and the sexual organs. [Kâshikâ 20]

The third degree of the manifestation of matter is the state of fire corresponding from the point of view of perception to sight, and to the senses of direction, of which the organ of perception is the eye and the organ of action is the foot.

The earth derives from the sun, which is for man the center of his universe. This is why it is represented by the guttural Gh (born of A, the principle). Then comes the liquid element, of which the organ of action in man is the genitals. It is represented by the cerebral Dh.

The solid state represented by the dental Dh corresponds to smell and to the function of rejection, whose organ of action is the anus. In Nandikeshvarä's text, the inversion of anus–sexual organs (Pâyu-Upasthä) for sexual organs–anus seems to have come about for metrical reasons, although some have chosen to see an allusion to Tantric practices; the sexual organ was viewed as the producer of semen, connected with the sense of smell and a means for sexual communication, while the anus was seen as the residence of Kundalini (coiled energy).

JA-BA-GA-DA-DA-SH: THE ORGANS OF PERCEPTION

"In all living creatures the ear, the skin, the eyes, the nose, and the tongue are the five organs of perception. [They are oriented] toward the exterior and correspond to J-G-B-D-D" (Kâshikâ 21).

KHA-PHA-CHA-THA-THA-CHHA-TA-TA-V: THE VITAL ENERGIES

"The five vital'energies (prânä[s]) correspond to the second (aspirated) letters of each group: Kh, Ph, Ch, Th, Th. Kh is combustion (prânä, respiration-digestion); Ph is elimination (apânä); Ch (samânä, distribution-circulation); Th (udânä, reaction, force); Th (vyânä, planning and specialization)."

CHHA-TA-TA: THE INTERNAL FACULTIES

"Ch-T-T follows. These are the first consonants of the three middle groups of the Vargä series; and it is these which symbolize the internal faculties (antahkaranä)" (Nandikeshvarä Kâshikâ 22–23).

There are three of these faculties: the mind (manas), which discusses; the intellect (buddhi, including the memory), which decides; and the Ego (ahamkarä), which acts. The fourth of these internal faculties, the consciousness (cit), is treated separately, for it is an omnipresent principle. The palatal C represents the mind, the cerebral T the intellect, and the dental T the feeling of autonomy, the Ego.

There is a connection between Chh (sâmanä, circulation) and C (manas, the mind); between TH (udânä, force) and T (buddhi, the intellect); and between Th (vyânä, specialization) and T (ahamkarä, the Ego).

"Universal Nature (Praknti) and Universal Man (Purushä) are represented by the initial consonants of the first and last group: K and P" (Kâshikâ 24).

Now that we have defined in man (the microcosm) the elements that correspond to the constituents of the universe in the creative principle, we shall return to the First Cause, to the origin of all forms of existence; to the fundamental dualism.

K (the first letter of the first group) evokes nature, Prakriti, the substance of the universe, which is considered to be a feminine principle; P (the first letter of the last group) represents Purushä, the plan of the universe, considered to be a masculine principle. [Kâshikâ 24]

SHA-SHA-SA-R: THE THREE GUNÄ.

"Sattvä, Rajas, and Tamas are the three fundamental tendencies that form the nature of the world. They are represented by Sh, Sh, and S. The Great God (Maheshvarä) can act (create the world) by becoming incarnate in these three tendencies" (Kâshikâ 24).

The palatal Sh represents Rajas, the tendency toward gravitation (and toward equilibrium between the contrary forces which permit the formation of atoms and worlds). The cerebral Sh is Tamas, the centrifugal force (which animates and creates but also disperses and destroys). The dental S is Sattv3, the centripetal force of attraction (which concentrates, conserves, and protects). These three tendencies are characterized by the colors red, black, and white. They are personified in the three divine aspects of Brahmâ, Shivä, and Vishnu. Shivä is the ultimate principle: the principle of expansion, from which all else stems and to which everything returns at the end.

The last formula of the Maheshvarä sûträ represents a return to the principle, the beginning and end of all existence, to the Being who stands motionless outside and beyond the world. According to the Shivä Âgamä, "the letter H represents Shiva in his aspect as the ultimate principle." "Beyond the creation, beyond all that which can be defined, I am H, the Supreme Witness, the sum of all mercy. Having said that, the peace-giver (Shambhu) disappeared" (Nandikeshvarä Kâshikâ 27).

With this, Nandikeshvarä's analysis of the Maheshvarä sûträ comes to an end. His commentator adds: "The letter A, the first of all the letters, represents light and the supreme deity. The I (aham) is formed by the union of the beginning (A) and the end (H)."

The Ego, the center of all individualized consciousness, allows the living being, like universal man, to be the witnesses through whom the divine dream becomes apparent reality; the Gnostic Christians interpreted this formula as Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet.

Creation by the Word

NANDIKESHVARÄ'S theory is an attempt to explain the fact that linguistic symbols can be used to define and describe the world of ideas as well as the world of matter, and that they can be the instrument of science and of thought. The way in which the original language was revealed to (or discovered by) mankind is of little importance. Nothing is changed by this revelation being instantaneous or a drawn-out process. Creation develops according to a preestablished plan, like a fetus. It is neither more nor less likely that language stemmed from the Damaru (Shivä's little drum), whose rhythm symbolizes the origins of life, than that it was slowly formed in the dull-witted intellect of half-apes: one myth is as good as another. The possibility of language must necessarily preexist its discovery and use. Its point of departure lies not in changing customs but in eternal principles. The extent of our possibilities of knowledge is determined by the limits of language.

Monosyllabic Dictionaries

ONE can find in India monosyllabic dictionaries that analyze the meaning of the various components of a syllable, and the corresponding elements in the various orders of reality.

In the realm of Yogä, particular vowels are associated with specific colors. Color differences are due to the frequency of light waves, just as musical sounds are defined by the frequency of sound waves. These in turn can be placed in parallel with the vowels of the spoken language. Nevertheless, because of the lack of simple instruments to measure the frequencies of the light waves, and because of the limited range in the spectrum of colors, the parallels between sounds and colors are imprecise. According to Raghunandanä Sharma's Aksharä-Vijñâanä (in Hindi), the fourteen vowels correspond to the following colors:

| A = white (shvetä) | Å = cream (pându) | |

| I = red (raktä) | Î = copper (tâmrä) | |

| U = yellow (pîtä) | Û = faun (Kapilä) | |

| Ë (ri) = bluish-black (krishnä) | E (rî) = browny-black (shyâmä) | |

| Ü (lri) = smoke-color (dhûmra) | Û (lrî) = orange (supishanga) | |

| É = red-brown (pishangä) | È = mother-of-pearl (trivarna) | |

| Ó = speckled (shabalä) | Ò = black or gold (karvandhurä) |

These letters and colors correspond to those which characterize the cycles in which new human species are born and die. We are currently at the end of the seventh cycle (manvantara), which is characterized by the vowel Ë and the color bluish-black.

Modern Indian grammarians have attempted to trace, in the most varied of languages, the origins of certain words, on the basis of the information given in the Maheshvarä Sûträ. For example, the word devä (god), comes from the root div, meaning "shining" (an epithet of the sun). I represents shakti, or energy. D is sight; V derives from U. Div therefore corresponds to "materialized, visible energy."

The root vid (from which comes Vedä) is the opposite and reflection of Div. Div is the divine light; vid is its reflection—sight, knowledge, revelation. The English word God and the German Gott derive from the root go, meaning "bull," the animal sacred since prehistoric times as the incarnation of Shivä-Dionysos. G means "hearing" and Ó means "the principle present in its manifestation." Gó therefore means "revelation." In the same way, crown, a symbol of royalty, comes from the root krn, which means "horn" and refers to the divine character of royalty (K = Purushä, man; R = agni, fire; N= earth), or man shining out on earth.

Magic Formulae (Manträ)

THE meanings given to the different elements of language are not simply attribution. There is a true correspondence between the formulation of the Word and the structures of living beings and the material world. This can be verified by the power of the Manträ(s), or magic formulae.

Some syllables not only have a descriptive value, but can also become a path of action, the means of summoning a subtle principle. The real presence of a divinity can be summoned into his image through the power of a Manträ. A typical example of a Mantra is the Christian formula of consecration, which, in its Aramaic form actually changes the bread and wine into the flesh and blood of Christ; but in translation it can only evoke the mystery. The translation of words that are magical in nature renders the rite ineffective.

The magical power of words is not necessarily linked to their apparent meaning. This is the case with all Manträ(s): they play an essential role in all magical rites. The syllable with which many mantra(s) begin is the one which opens onto the universal: the syllable AUM (or more precisely AU , as it appears in Tantric rites).

, as it appears in Tantric rites).

One section of the Chhândogyä Upanishad is devoted to the various correspondences between the components of that syllable and the different aspects of the manifest world. Many other texts discuss the same subject. AUM is considered in a symbolic sense to be the syllable from which all others have stemmed. It contains all the elements of language since it is formed from the three points of the triangle (throat A, lips U, and nasal resonance  ), within which all the points of articulation and hence the entirety of language are to be found. In day-to-day usage, the

), within which all the points of articulation and hence the entirety of language are to be found. In day-to-day usage, the  is replaced by M in order to avoid accidentally summoning the magic powers of the Manträ. A represents the principle of the world; U is the manifest principle;

is replaced by M in order to avoid accidentally summoning the magic powers of the Manträ. A represents the principle of the world; U is the manifest principle;  is hearing; AU

is hearing; AU summons the principle of the world manifested in the Word.

summons the principle of the world manifested in the Word.

Much of the time we use words without knowing their true meaning: yet they have their revenge; for when we use sounds whose meaning is the opposite of what we attribute to them, and regard approximations as realities, we live in absurdity, and the results we obtain are contrary to those we are seeking. This is typical of most modern ideologies, which are based on key words whose meanings are other than what is attributed to them. Language, as the instrument of knowledge, is a powerful weapon whose misuse brings us quickly to disorder.

Elements of the Musical Vocabulary

STEMMING as they do from common principles, the divisions of articulated sound, just like those of musical sound (whose limits define our possibilities for communication), can be found in all the harmonies and proportions that form the universe. It is through the study of these harmonies—whose most immediate image is the phenomenon of music—that we can have insight into the harmonic nature of the stellar and planetary worlds as well as the structure of atoms, of the subtle and material worlds, both invisible and perceptible; we can then also understand the parallel universe which exists inside us, and which we perceive in the form of sensations and emotions, and whose mechanisms we can, through the introspection of Yogä, analyze and put into arithmetic formulae. The possibilities of articulated sound, like those of musical sound, are limited by inexorable and parallel laws; these are dependent upon the possibilities of our discrimination and perception, which establish the limits of the aspects of the world which we can and must perceive.

In the musical language, the intervals, which have a precise expressive significance, are in Indian musical theory called Shruti(s) (perceptible musical intervals). These Shruti(s), which form the base of all the musical languages, are fifty-four in number, just like the phonemes of spoken languages. In modal music like that of India, twenty-two of these intervals have a predominant role in the psychological action of the music.

The Various Forms of Language

SPOKEN language is not the only means of communication. There are linguistic possibilities, means of expression and communication linked to each of the states of matter (bhûtä) and each of the corresponding senses of perception and action.

The language of odors, tied as it is to the solid state of matter, is the most elementary. It plays an important part in the reproduction of the species. Odors and perfumes are signals: some animals (wolves, dogs, etc.) mark their territory and recognize their friends and enemies, their prey and food, by means of odors.

We use the language of taste, corresponding to liquid elements, as a guide to the alimentary process, the precondition of life.

The sense of touch, connected to the gaseous element, is rather rudimentary in man, with the exception of the aspect linked to auditory perceptions. The sound vibration is only perceptible to us because it is transmitted by the pressure of air, for our direct perception of the waves of ether is not developed. Some insects are not subject to the same restrictions, but we need a decoder in order to transform radio waves into audible sounds.

Visual Languages

CONNECTED as it is to the element of fire and to light, visual language is almost as important as spoken language. It is the realm of gesture, of symbols, of hieroglyphs and ideograms, and even to a certain extent of the forms of writing, which transpose audible sounds into visual symbols.

The language of Mudrä(s) (symbolic gestures) is used in ritual and dance, and allows the expression of concepts independently of any sound aspect. It is thus not linked to a spoken language. The same is true of ideograms; writing with ideograms, which are formed of visual elements not directly linked to sounds, is on a more abstract level than phonetic writing. Writing tends to alter and paralyze the evolution of a language, even though it is an artificial memory that allows the conservation and transmission of ideas.

A Geometric Language (Yanträ)

THE visual language of symbols makes use of elementary geometric forms, corresponding to the phonemes of the spoken language and to the numerical intervals of the musical language. Through their mathematical connections, the Yanträ(s) reflect the fundamental structures of matter and the principles of life in a more obvious way than does spoken language.

"Einstein and some of his successors, such as Wheeler, when they constructed the theory of general relativity, have put forward the idea that everything is geometric at base" (D'Espagnat: La Recherche du réel, p. 81).

Yanträ(s) allow the representation of particular states of being. There is a Yanträ and a Manträ for each god; they are an expression of his nature and enable us to summon him.

Yanträ(s) thus play an essential role in ritual. The anthropomorphic images are proportioned according to canons based on Yanträ(s) and are accompanied by accessories that call to mind the role and the individual characteristics of each god. The Yanträ(s) are essential to all magical accomplishment; they are also the basis of the plans of temples and the proportions of all sculpture. The artist first of all draws the Yantra of a god and then, within the limits thus established, he brings out of the stone the anthropomorphic image that was concealed within it.

The human body is formed according to particular proportions and harmonies, which are the secret of its beauty. By means of yogic introspection we can perceive geometric diagrams in the subtle centers, connected to the sound symbols which define the body's role and actions. The Yanträ(s) are the expression of the constants that are to be found at the base of all the structures of the world, of atoms as well as of galaxies, of the genetic components of life and the mechanisms of thought. They are also a key to the mechanisms of our emotions.

In musical intervals we can analyze the psychophysiological action of purely numerical relationships that cause emotive reactions in listeners. This suggests the possibility of a mathematical definition of our reactions and feelings.

THE POINT

In the language of the Yanträ(s), the point (bindu) represents the transition from nonmanifest to manifest. All manifestation must start from one point. It corresponds in Manträ(s) to Anusvarä, the nasalization of syllables.

THE SPIRAL

The symbol of ether, the principle of the development of space and time, and of the expansion of the universe, is the spiral, which, starting from the initial point, develops indefinitely with circular movements like the universe itself. It corresponds to hearing (hence the labyrinthine shape of its organ, .the ear). The corresponding Manträ is Han, the guttural semivowel, stemming from A. The spiral is perceived in the experience of Yogä in the center of purity, situated in the throat.

THE CIRCLE

The symbol of the gaseous element of air is the circle, or occasionally the hexagon. It corresponds to nondirectional movement perceptible by touch.

It is from the gaseous state that the other elements are born through orbitation or condensation. It is thus the first manifestation of the energetic principle represented by the Manträ Ya , the semivowel Y, stemming from I (energy,

shakti). The corresponding color is blue-black. The principle of the gaseous element is achieved in Yogä in the center of spontaneous sound (Anâhatä Chakrä) close to the heart.

, the semivowel Y, stemming from I (energy,

shakti). The corresponding color is blue-black. The principle of the gaseous element is achieved in Yogä in the center of spontaneous sound (Anâhatä Chakrä) close to the heart.

THE TRIANGLE

The symbol of the liquid state is the triangle, resting on its point, which is also the symbol of feminity. A simple horizontal line can also represent the liquid state, for water always tends toward a leveling. Its corresponding sense is that of taste. Its Manträ is Va , deriving from U. In Yogä it is perceived in the center of the Svâdhishthanä, at the base of the sexual organs. Its corresponding color is blue-green. The symbol of the fiery state is a triangle with its point at the top (the masculine symbol), or simply a vertical line: fire tends to rise. The corresponding sense is that of sight; its Manträ is Ra

, deriving from U. In Yogä it is perceived in the center of the Svâdhishthanä, at the base of the sexual organs. Its corresponding color is blue-green. The symbol of the fiery state is a triangle with its point at the top (the masculine symbol), or simply a vertical line: fire tends to rise. The corresponding sense is that of sight; its Manträ is Ra , derived from Ë (ri). It is perceived in Yogä in the center of the navel (Nabhi Padmä). Its corresponding color is red.

, derived from Ë (ri). It is perceived in Yogä in the center of the navel (Nabhi Padmä). Its corresponding color is red.

The triangle, symbol of femininity, illustrates the numerical relationship 2 (base) above 3 (triangle) corresponding to (2/3), that is, C–F (Do–Fa), or a fourth in music, a gentle, feminine interval.

The masculine principle shows the relationship of 3/2. In music this is the frequency ratio of the fifth, C–G (Do–Sol), a sparkling, masculine interval. The six-pointed star represents the union of principles, the erect phallus in the vulva.

The cross too is a symbol of the union of water and fire: the union of opposites, which is the origin of the perceptible world.

THE SQUARE

The square is the symbol of the solid element or earth. It corresponds to the sense of smell, to the color yellow, and to the syllable La (deriving from Ü). It is also the symbol of the god Brahma, the shaper of the world, riding on the elephant Airavatä.

(deriving from Ü). It is also the symbol of the god Brahma, the shaper of the world, riding on the elephant Airavatä.

THE PENTAGON

The number 5 (Shivä's number) is the symbol of life and of consciousness. At the base of all living conscious structures is to be found the factor 5 (five senses, five fingers, five places of articulation, etc.). The crescent moon, used as a symbol, has the shape of the moon on its fifth night and thus stands for the number 5.

In music the perceptible and emotive intervals are those which include the factor five (harmonic third 5/4, minor third 6/5, harmonic sixth 5/3, minor seventh 9/5, etc. (See Alain Daniélou, Sémantique musicale.) Various aspects of the living being reflect symbolic features: such are the hand (with its five fingers), the erect phallus (the axis or column, symbol of the continuity of species), the eye (the sun), and the ear (a labyrinth).

The Swastika

THE swastika is the symbol of the irrational. It reminds us that the principle which is at the origin of the world, and the universe itself are twisted (vakrä). Any explanation that seems to be simple and logical is inevitably wrong. Starting from the nonspatial point (bindu), the universe develops in a spatial form; this is represented by a cross, image of the union between Purushä and Prakriti, the masculine and feminine principles. But this space is twisted: one becomes lost in space if either the inner or the outer branches of the swastika are followed. One never reaches the center. It is necessary at a given point to change direction and reject apparent logic. This is why in mathematics the irrational numbers are closest to reality. The prime numbers, which defy simple logic, are the only important ones.

The geometry which we know as Euclidian is merely approximative and has very narrow limits. In music the cycle of fifths, which seems to be a rational base, is exact only until the fifth fifth. Social theories, the relationships between human beings and the rites or relationships with the subtle beings, are never simple. All slogans are by their very nature wrong. For this reason the swastika is a beneficial sign: inscribed on the door of a temple or a house, it reminds us that there is no logical solution to any problem and that all simplification leads to absurdity.

Any science or technology or philosophy or religion that claims to be in possession of the truth is illusory and dangerous.

The god Ganeshä, who is both man and elephant, is the iconographical equivalent of the Svastikä. He evokes the identity between the macrocosm, the immense being, and the microcosm, the human being. He defies logic. One cannot be at the same time small and large, immortal and mortal, god and man, but nonetheless there exists a fundamental identity between irreconcilables. The divine principle is that in which opposites coexist, and so it is likewise in the divine work, in all the aspects of the created world.