“Came to believe”: The three most beautiful words in our language.

—ANONYMOUS

Beliefs alter our perception of reality. They also affect our language and direct our actions. Beliefs about suicide directly affect our treatment and understanding of the suicidal thinker.

If we believe in the suicidal thinker’s capacity for self-improvement, he has a better chance of improving. If we believe his situation is hopeless, his chance for change is greatly diminished, and the situation is far more likely to end in disaster.

If we believe the suicidal thinker’s problem will simply resolve itself, we are denying reality and refusing her what she deserves: our love and compassion. If we believe in our ability to grow and change as she does, we feel less threatened by her progress and are therefore less likely to compromise her achievements, however unconscious our actions may be.

We are more likely to use new communication skills, take a more effective course of involvement, and learn how to let the suicidal thinker fumble through life if we feel comfortable with ourselves. Such efforts contribute to a more productive healing environment, allowing him to do the work necessary to break the cycle of destruction.

The following beliefs are, I feel, crucial to establishing a healthy, loving environment in which the suicidal thinker can find relief, comfort, reassurance, and support:

- Secrets are deadly.

- It’s okay to talk about it.

- It’s a family challenge.

- Change is possible.

It’s a given that secrets underlie most suicidal thoughts, secrets like sexual abuse, battering, or severe loss. Often the suicidal thinker can’t even easily recall these secrets. Clearly those secrets need to be flushed out, but here I speak only of the crisis at hand. Beware: if the suicidal crisis is continually buried in secrecy, the suicidal thinker might end up buried as well.

We’ve all been trained to discount trauma, keep our chin up, look on the bright side. This attitude, however, can lead to fear, shame, and confusion, feelings that make it difficult to give and receive productive emotional support. By acting on the belief that secrets are deadly and establishing an open line of communication, you give the suicidal thinker an outlet for the turmoil that’s eating at her soul. If you remain closed to the reality of her life, you contribute to her destruction. It’s as simple as that.

Your loved one’s suicidal thoughts are not going to disappear by shutting them out. This is not a game; she could wind up dead or with permanent physical damage.

If someone in your life has made a suicide gesture or has come to you talking of suicide, there’s a good chance that person will continue in the same vein until he or she breaks the cycle, either by outthinking the brain or completing the suicide. It’s hard to hear someone talk about suicide, I know. If you tend to squash or interrupt the suicidal thinker with words like, “Oh, come on, that’s nothing,” or “Why can’t you forget about it?” please try the following exercise.

EXERCISE: COMMUNICATION

- When a suicidal thinker or depressed person comes to you needing to talk, stop whatever you’re doing (turn off the TV, put down the newspaper, close the book or laptop, turn off the radio, take the skillet off the stove).

- Tell her you’re there for her 100 percent.

- As she talks, look her straight in the eye. Nod your head. Say, “Um-hmm.”

- If she starts to cry, let her cry and sit in silence. You may feel compelled to fill the silence with words. Sometimes it’s best to sit quietly and let her release the tears. Please do not say, “Don’t cry,” or “Don’t be so sad.”

- Breathe deeply while she shares. Most likely your level of discomfort will start to rise. Perhaps sip a glass of water while she talks to give yourself something to do without diminishing your attention.

- As she speaks, cries, or vents her anger and confusion, look at her neutrally with love and compassion. Try not to display shock, anger, or fear.

- If you begin to feel angry and defensive as she shares, remember to breathe deeply to keep your equilibrium. Wait until you are away from her before you let the anger out. Go for a drive and scream; call a trusted friend and tell him about it. Be sure to release any anger, but not in her presence.

- If you need a breather while she’s sharing because it’s getting too intense, say, “I love you, ______, and I’m really concerned. Let me just take a minute and collect my thoughts.” Ask if you can hold her hand during the silence. If she declines, say, “Okay, that’s fine. I just thought I’d ask,” and let it go. After a minute, ask to continue the discussion.

Often this type of discussion is spontaneous, and the listener has very little time to prepare. If you have the opportunity, however, I suggest that you practice (or role-play) this exercise with someone else to get a feel for it. A “dress rehearsal” can help lessen potential discomfort.

Despite what I heard growing up—“No one wants to hear it”—talking about my feelings was the only way I got better.

In the beginning of my self-exploration (mid-1980s to early 1990s), I often felt shut out and rejected when I spoke openly to family members about the ways in which I was seeking help, particularly when I spoke about therapy. How sad it is that the effort to reach out for help—a powerful, courageous act—is often repelled because of another person’s inability to witness pain.

Had I not found Sylvia, the people from Twelve Steps, a community at First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church, and other travelers on the road to self-discovery, I couldn’t and wouldn’t have made it this far. Because of their honesty and willingness to be vulnerable, I finally saw that I was not alone and there was nothing wrong with me for feeling the way I did. These people made it safe to vent all the crap I’d been carrying around for a good twenty-five years. They let me do and say what I needed to break the suicide cycle.

Because of the safety found in these arenas, I became strong enough to approach family members and begin to heal those relationships. After I was hospitalized and the truth could no longer be denied, things started to shift even further. But it was still a long, arduous haul. Over time my struggle was openly acknowledged and it felt safer to express my truth, though all of us were still fumbling our way through each step.

I began to voice questions and set boundaries. I said and asked many things. To nearly everyone: “I need you just to listen and not tell me how to feel.” To my father: “How did you feel when Mom died?” or “I need you to turn off the TV when I’m talking to you.” To my three oldest siblings: “What was it like when my mother came into your lives?” To my sisters: “I don’t need another mother; my mother is dead. I need a sister, a friend.” To people who liked to poke fun at me: “If that’s how you express love, then I don’t want it.”

I began to feel like a person with feelings and thoughts instead of an outcast or damaged goods. I began to feel accepted for who I was and not judged for what I felt. I started to translate my distortion of reality into a language I could comprehend and clarify. The feelings and thoughts were no longer trapped in my cerebral pressure cooker.

It’s okay to talk about it. While I advocate positive thinking and “acting as if,” I say phooey to the theory of putting on a happy face despite internal strife. We all have problems, and we all need help. Anyone who claims otherwise is from another planet. The suicidal thinker needs to know he can share his experience with others: his friends, family members, and professionals. After all, what is more important, the “family image” or the life of your child, spouse, sibling, or friend?

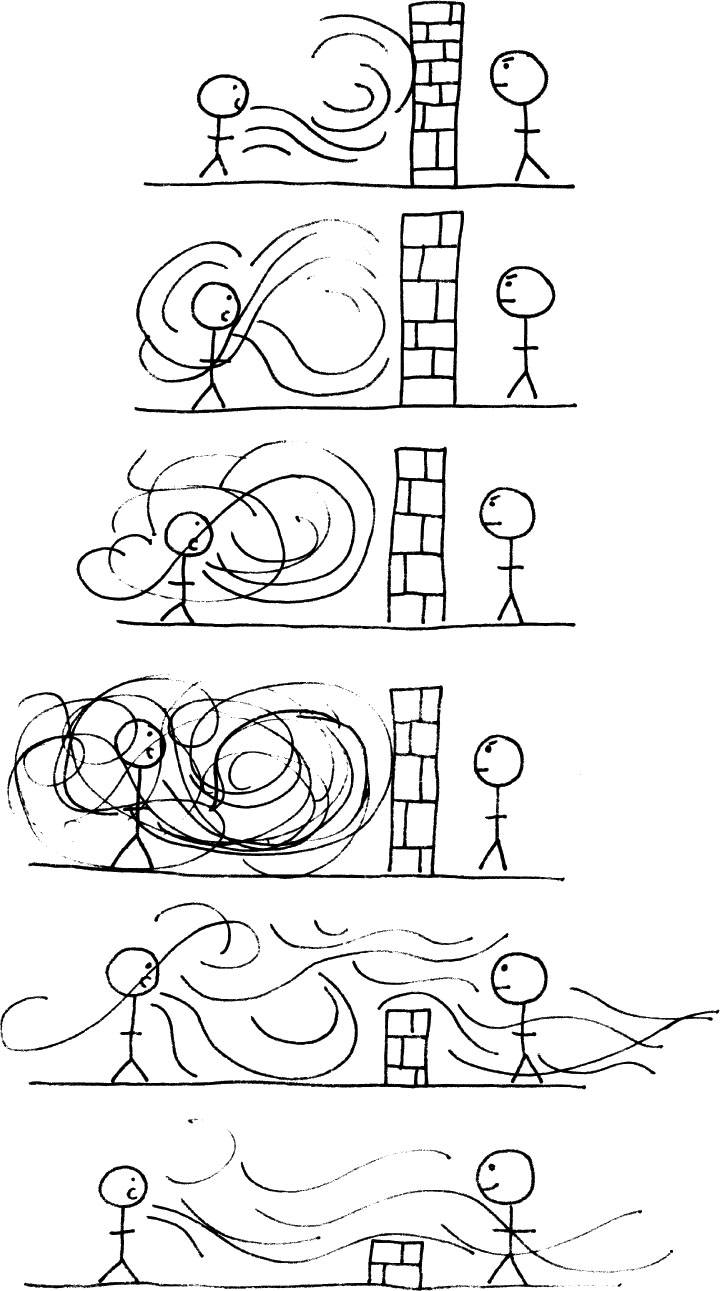

In 1996 I was asked to give a presentation on depression and suicide to parents of teenagers. I used the illustration on the following page to show what happened to me as a teen when I tried to share difficult feelings with my father. I call the drawing “The Wall” because that’s exactly how it felt.

The Wall was so high that my feelings and thoughts had nowhere to go. They just swirled backward, surrounded me, and pulled me deeper into their web. Because I had no healthy outlet for my feelings, they inevitably turned to frustration and anger, which quickly boomeranged back at me—and were translated into suicidal thoughts.

When I was in my late twenties and my father and I began to heal our relationship, The Wall started to drop. I finally felt like my feelings were heard and respected. Instead of swirling back at me, they floated over The Wall. Sometimes. Like any relationship, ours was far from perfect, but we both worked hard to improve it.

THE WALL

* * *

We are all members of the same human family, wanting and deserving love, respect, and acceptance. Believe that it’s okay to talk about it, and show the suicidal thinker: “My door is open. Anytime you’re ready to talk, I’m ready to listen.” If she doesn’t respond right away, try not to badger her for information. Just remind her that she is loved and when she’s ready, you are there. (Of course, if the suicidal thinker is making gestures, it is imperative to seek professional support and guidance, even if she doesn’t want to talk about it.)

Please remember: if you’re opening the door to listen, you must be prepared to do so. See the “Actions” chapter for tips on listening well, practicing compassion, and setting boundaries. I suggest that you practice these skills with a friend.

Suicidal thoughts are products of experience, history, and genetics. Suicidal gestures manifest not from thin air but from a breakdown in the generational chain—a breakdown of biology, communication, behavior, understanding, trust, or circumstance.

To peg the suicidal thinker as the “troubled one” in the family is a severe disservice. Most often that person is highly sensitive, intelligent, and creative, with deep feelings and a finely tuned emotional radar that tends to intensify family undercurrents.

It’s important to believe that suicide is a family challenge. Suicidal thinkers are not in it alone. They are card-carrying members of a family system, a direct product of their immediate environment and upbringing. The family is how and where our personality develops.

Instead of looking for causes outside the family structure or pointing the finger of blame at the struggling relative, I encourage you to look within the circle and within yourself. Be honest: Does someone in the family have an addiction problem? Is there a history of suicidal behavior in the family? Eating disorders? Depression or other mental disease? Was there severe trauma with the loss of a parent or sibling? Is there a possibility of sexual abuse? Was there divorce?

Is there something you can do to help the situation? There are many possibilities: renewing your commitment to meet your own needs; talking more openly with your spouse; addressing an addiction problem; finding more time for the suicidal thinker; learning how to be a better parent; finding grief support. I’m well aware that taking such steps is easier said than done, but the sooner the truth is approached and addressed, the sooner you and the suicidal thinker will find relief. If that person has already entered the cycle of suicide gestures and hospitalizations, it may be harder to break the pattern, but any positive change on your part is better than none.

This is a long journey—for everyone. Some say crisis brings people together. That is certainly true for the Blauners. We have weathered enough for several families, and I can honestly say that despite any unfinished business between us, I feel closer to my immediate family than I ever thought possible. That doesn’t mean I have a perfect relationship with each and every person, but I do have friends within my family. I try to accept them for who they are, quirks and all, just as they try to accept me, quirks and all. We are all imperfect, and we all make mistakes, but after many years of mending, stumbling, and embracing, when I’m in their company I look around and see loving people doing the very best they can.

The only sense that is common in the long run is the sense of change—and we all instinctively avoid it.

—E. B. WHITE

Change is definitely possible. I am living proof. Change is not only possible, it is inherent to our existence. Folks who refuse to change or think they’re too old, too young, too whatever, are mistaken. If my father could begin changing at the age of seventy-nine, anyone can.

If we want to support the suicidal thinker, we have to believe in her ability to change and our ability to change with her. Had I listened to people’s doubts in me I would have never accomplished some of the greatest achievements in my life: driving alone across the country; finding a place to live and work once I reached my destination; writing this book and getting it published; buying a house; leaving jobs for better ones. I wouldn’t have had the guts to follow my intuition, to leave a long-term relationship that was over long before I finally left it, to believe in god, to trust in therapy.

Change begets changes. If we maintain the belief that change is a good and natural thing, then our resistance to the boat-rocker might lessen. We will let the boat-rocker outgrow his old role as a suicidal thinker and embrace him in the new.