4

Improve Personal Productivity

Many years ago, I had a very capable individual working for me, somebody whom I thought very highly of, the kind you proclaim as ‘excellent’. When a very senior position opened up, I grabbed the chance to elevate that person to that senior role. After a year, much to my dismay, things did not work out and I had to actually move that person from that role to a less challenging one. I reflected on the whys of it and realized that while the person had all the necessary skills and capabilities for the role—while he had a well-developed experience algorithm—he did not possess the necessary productivity to make a complex role work. He could not handle the multitasking the complex role required—the fact that many things have to be done at the same time and you have to be on top of all of them—could not decide which meetings to spend time on, which issues needed long deliberations, which issues should not be allowed to take more than five minutes, and so on. None of these were capability issues. If there were forty-eight hours in a day, that person had all the tools and wherewithal to succeed. But there are only twenty-four hours in a day, and that is where productivity comes in.

That episode taught me that success is a partnership of the experience algorithm and productivity. The algorithm is your ability to respond to a situation and get to the right answer; it is the ability to generate solutions to complex problems. In a way, the experience algorithm is the summary of your capabilities. That summary of capabilities has to be put to productive use to be able to finally create value and a favourable output. The output, then, is a multiplication of the algorithm and the productivity used in employing it. We have all seen different kinds of people. There are people who are highly capable and dazzle with insights, strategic thinking and knowledge, but at times they leave you exasperated by their lack of output and their inability to get things done and manage complexity. These are the people who are often labelled as high potential, but are yet to fire fully. They possess a high-quality algorithm but are poor on productivity. Then there are those who are moderate on capability, cannot create breakthrough solutions or strategies—in effect, have a moderately developed algorithm, but seem to get things done when told what to do, follow up diligently and are very disciplined about timelines, commitments, etc. Such people are often referred to loosely as the ‘doers’. They are high on productivity but moderate on the algorithm.

Real high performers, those who achieve exceptional success, are those who are good at both. They have a highly developed algorithm which they employ with the highest productivity and hence are able to deliver both high quality and high quantity of output, making them highly successful in their careers. Such people are few and far between. If you want the highest level of success in your career, you have to aim for that high bar of both, a fantastic algorithm representing the summary of your capabilities and excellent productivity to convert that algorithm into output. Productivity is the means by which you convert your algorithm into output.

Most people who want to succeed do seem to realize the need to grow their algorithm/capabilities as a necessary prerequisite for success. I describe it using the phrase ‘experience algorithm’. These people might not describe it the same way, but they all understand that if they have to achieve higher success, then they have to continuously grow their capabilities. There is a high degree of awareness that success requires capabilities, and that if I have to be successful, I have to make an active effort to grow my algorithm, or whatever words I use to describe it. However, interestingly, there is not the same degree of self-awareness about the need to grow productivity, and so there is often no effort put into increasing it. This is one of the most important mistakes people make, and is often the reason they don’t achieve the full success they otherwise can.

The reason for this lack of effort in growing one’s productivity is two-pronged. The first is the lack of self-awareness—as I mentioned above, most people are aware that to succeed, they have to grow their skills and capabilities, their algorithm, but they don’t realize that it is equally important to grow their productivity. The second reason is the mistaken assumption that productivity grows by itself—the thought that if you work hard every day, if you keep achieving results, your productivity will grow by itself. It is the same myth that I pointed out in the context of experience—the mistaken assumption that if you keep working hard and putting in time, your experience is building up by itself. The same myth is prevalent to an even higher degree in the context of productivity. No, folks, productivity does not grow by itself; it has to be catalysed to grow.

In this chapter, I want to deal with these two issues: first, to make you aware that you need to improve your productivity, and second, to show you some techniques by which you can catalyse the growth of your productivity.

The ‘Why’ of Productivity

Why do you need to grow your productivity? Why is it so important for long-term career success? As people go up the corporate ladder, get to higher positions, here is what happens. They must have built up the higher order algorithm and capabilities to succeed at the higher level, so let us assume that is the case. But is that enough? As they go higher, the demands of the job also rise—no company gives you a higher order job, higher title and higher pay without having a higher expectation of output from you. You don’t go higher with the ask being the same. To deliver that higher ask, let’s say you have built up the higher order algorithm. But apart from that, you also need more time and energy to meet that higher order ask. Unfortunately, as we all know, time is a constant at twenty-four hours a day. I always say, the only thing common between a watchman and a chairman is twenty-four hours a day. If somebody progresses from being a watchman to a chairman—and I do wish everybody such great success in their careers—they have to deal with the fact that they have to meet the requirements of being a chairman with the same twenty-four hours they had as a watchman. As you get to senior levels, two things change: first, the complexity of the problems/issues you deal with, and second, the number/quantity/breadth of the issues. Superior capabilities and algorithm helps you deal with the higher complexity of the problem, but it is only higher productivity that will help you deal with the quantity/breadth of issues. At senior levels, the number of people who want your time is far greater than the time you have, the number of things that need your attention is far greater than the number you have handled earlier and the number of simultaneous things you have to manage is far greater than what you have ever done. The breadth is such that one day in the morning, you could be discussing the long-term strategic plan and in the afternoon the same day, you might have to deal with next week’s issues. There is an exponential change in the number/quantity/breadth of issues that you have to deal with as you climb up the corporate ladder, and to manage that, you have to drive an exponential increase in your productivity as well.

Again and again, I have seen people move from junior to middle levels and then to senior levels, and fail somewhere on the way. Usually, their failure at the higher levels is mistakenly attributed to a lack of capability. It is not that. Often, it is because they have not grown their productivity in proportion to the higher ask of the senior level. And folks, a productivity increase does not happen by itself, it can’t be taken for granted—it has to be catalysed by you.

A classic manifestation of this was a senior person with a fairly independent responsibility. This person was overworked, overwhelmed and trying his level best. Yet, the business was going nowhere, people were unhappy and there were no results to show. This person saw himself or herself as Atlas, carrying the entire load of the business on his or her shoulders, often externalizing to say everything is broken and needs to be fixed, and hence he or she has to work fourteen hours a day and so on. These are classic symptoms of poor productivity—lack of knowing how to be productive in a complex environment, how to organize oneself and manage your energy and time. The Atlas stereotype is a positive mask, but it is a mask—it simply hides the real problem, which is poor productivity. So the next time you are working your butt off but nothing gets done, you know where the problem is. Or the next time you feel that the entire company, your team and your business needs you and you are Atlas and that is the reason you work so hard, you know what the problem is. It is poor productivity.

The ‘How’ of Productivity

Now that you are aware of the need to catalyse growth in your productivity, let us move on to how to achieve that. Productivity is a complex subject comprising many facets including time management, prioritization, discipline, learning to differentiate the important/urgent from the less important/less urgent, the art of delegation, the skill of multitasking and so on and so forth. Each of these aspects can be a book in itself, and I would encourage all readers to make an effort at getting better at each of them. A good way is through your TMRR process and reflection—identify what you think you need to get better at and then start to focus on that.

In this chapter, however, I am not going to focus on these various facets. Instead, I am going to share some of my experiences of boosting productivity, which catalysts have worked for me and how I have focused on growing my productivity. This is not a replacement for the facets above; these are just my beliefs and learning. I have found two methods that helped catalyse the growth of my productivity. One is derived from Stephen Covey’s concept of the ‘circle of influence’ and the other is my own method of allocating time to my priorities, something I call the ‘rocks first’ method.

Focus on the Circle of Influence

Two decades ago, I read Stephen Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, one of the greatest self-development books of the modern era. One of the concepts in the book that I found very interesting was that of the circle of influence. For those of you who have not read the book, I shall briefly explain the concept, focusing on those aspects which are relevant to increasing productivity.

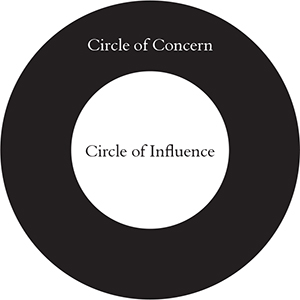

The core of the concept is that broadly, everything that has an effect on you, impacts you and is of consequence to you can be divided into two broad circles. One is called the circle of influence, which comprises all those things that you have an influence on, and the other is the circle of concern, which comprises things that impact you directly or indirectly, but which you can’t influence. These are two concentric circles—the inner circle, the smaller circle, which comprises things that you can influence, and the outer circle, the bigger circle, which comprises things on which you don’t have an influence. This is schematically represented in the drawing below:

While this concept can be used for all aspects of life, for the purpose of this chapter, I would like you to visualize this in the context of things at work. You dream of being very successful in your career, but to be successful, you must deliver high quality and high quantity of output at work. You must deliver results which are compelling so that people take note of them, and thus create a good reputation and long-term career success for yourself. For you to deliver those results, there are a set of things which are within your sphere of influence, in your circle of influence. Equally, there are things that impact your ability to deliver results at work that are not in your influence, and those are in the outer circle, the circle of concern.

As I became a senior at work, and started facing the productivity problems that all senior managers inevitably face, I felt, ‘I am working damn hard, yet I don’t seem to be producing results as easily as I did when I was a junior.’ I was quite confident that it was not an issue of my ability, and hence I knew I had to find the answer in my productivity, in where I spent time and how I organized myself to produce results. That is when I applied the concept of the circle of influence to productivity. I realized, through TMRR reflection, that I was most productive with my time when I focused on aspects within my circle of influence. In those things, I was like a magician, producing impactful results at will. Equally, I found through my reflection that there were areas on which I spent a lot of my time and still created limited output. Consistent TMRR in those areas led me to the conclusion that most of those areas were in my circle of concern. I realized that spending time on areas in my circle of concern was producing minimal results and was an extraordinary waste of my time, the greatest productivity killer I had.

There, folks, is my simplest, most obvious and yet super effective key to productivity. You are at your productive best when you focus on things which you have an influence on, which you can impact. Avoid spending time on areas where you don’t have any influence or impact. The other way of stating the same thing is that ‘highly productive people are those who spend all their time on things to which they can make a difference, where they have an influence’. Such people are highly productive with their time, and assuming they have good quality experience algorithms, they create fantastic value and results. Such an individual often gets a lot done for one person and can be rather awe-inspiring at times.

Of course, the benefits of this habit go beyond just productivity, as Stephen Covey explains. The more you focus on your circle of influence, the more it grows, and slowly and steadily, it starts to cover more of the areas that earlier fell under your circle of concern. Hence, this habit is also an effective means of growing your influence over time. I would urge readers to read Stephen Covey’s book for a clearer understanding. I am limiting my articulation here to the impact this has on personal productivity at work.

Let us further explore what happens when you don’t focus on your circle of influence and instead spend time on your circle of concern. Clearly, you don’t produce great results and value. Hence it is obvious that the circle of concern is a killer of productivity. But as I reflected on my own experiences, my TMRR told me that the impact was on more than just productivity. I realized that when I spent time in my circle of concern, I felt irritated, angry, frustrated, at times incapable of creating results and inadequate—a whole host of negative emotions. I came to the realization that the circle of concern was not just a productivity killer and a time waster, but it was, more importantly, an energy killer. And the biggest realization for me personally was that it kills energy disproportionate to the time you spend on it. I realized that I might have spent only half an hour on something that was in my circle of concern, but it often destroyed energy and created enough negativity to kill the productivity of a whole day.

This, then, is my second key to productivity—that productivity is not just about productivity of time but also about productivity of energy. I realized that the productivity of energy is destroyed by spending even a small amount of time on the circle of concern, and that energy loss has an impact even when you subsequently start focusing on your circle of influence. Time in the circle of concern is like poison—it takes only a small amount to have a negative impact on the larger whole.

Hence, my two keys to super high productivity, based on my learning in my work life, are:

- To increase your productivity, focus relentlessly on whatever is in your circle of influence. Spend all your time on what you can make a difference to, even if in the beginning it looks small.

- Avoid the circle of concern like the plague. It is not about how much time you waste there—maybe you can afford to waste that time—but the more harmful impact of it is the energy it destroys, the negativity it creates in you, which then has a cascading impact even on the time you spend in your circle of influence.

A question that often comes up in my sessions is—‘Does that mean I ignore what is in my circle of concern? What if some of that is very important?’ I do believe that you must summon the courage to ignore what is in the circle of concern and focus all your time and energy on what is in your circle of influence. That will create a virtuous cycle of productive results, wherein what is in the circle of concern will become less and less important over time. However, for a moment, let us assume there is something in the circle of concern that is so critical that it can’t be ignored. Let us say you are a salesperson who has been pursuing a new large deal for a long time. Finally, after many attempts, the customer gives you a trial order and you know that ensuring delivery of that order on time, with no quality defects, is important to create future business. However, this is in the hands of the supply chain team and not fully under your influence. What then is the right way to deal with it? There are two approaches one can take for what is in your circle of concern.

A truism of life is that everything that is in your circle of concern is in somebody else’s circle of influence. In an organization’s context, it could mean a co-worker outside your team, a vendor, etc. A good way of dealing with important things in your circle of concern is to identify in whose circle of influence they are, and then strike a partnership with that person. And for any partnership to work, there has to be a win-win situation. This means that there is something in your circle of influence which is of value to that person and you have to create value for him or her in return for your circle of concern issue being addressed. So the first approach is to strike up partnerships.

The second approach to dealing with things in the circle of concern is to find a path to them through your circle of influence. Let’s suppose that you are dependent on information and data from a colleague who is not in your team and whom you do not have adequate influence on. In the past, this individual has often given you poor quality information and this has impacted the subsequent work that you do with that data. Now, this is in your circle of concern, and thinking about this creates all the stress and negative energy that circle of concern items create. Are there paths through your circle of influence that lead to a solution? You could possibly call that person and actively teach and coach them how to collect that data and send it to you. In a way, you are doing something which that person’s manager should have done. You might think it is a waste of time, but doing this is better than being stressed about your circle of concern. Another possible path through your circle of influence is to give yourself enough time to check the data when it comes and to redo it if required. Both these approaches are within your circle of influence, stuff you can do. But what most people do is spend a lot of time agonizing about something in their circle of concern, in the process creating negativity and destroying productivity, instead of finding simple pathways through their circle of influence to issues in their circle of concern. In chapter 7, we will apply this approach of finding pathways through the circle of influence to the more complex problem of how to find a good boss, an issue that is in everybody’s circle of concern.

The ‘Rocks First’ Method

Apart from the circle of influence approach, the other method I have personally used to keep my productivity high is the ‘rocks first’ method. Before I talk about it, I would like to narrate a story that I am sure each one of you has come across at some time or the other. A teacher takes a glass jar and places it on the table along with some sand and rocks. In the first instance, she pours all the sand into the jar, which becomes nearly full, and thereafter can accommodate only a couple of rocks. In the second instance, she puts all the rocks into the jar and then pours the sand on top of that. The sand flows into the spaces between the rocks. A fair amount of sand is in the jar, only some is left. So in the first instance, all the sand is consumed but very few rocks; in the second instance, all the rocks and a good quantity of the sand are consumed. The trick lay in putting the rocks in first. The teacher then goes on to tell the class that the rocks are the more important things in your life—your health, your relationships, your learning, etc. The sand is the less important or trivial things. If you come to the rocks after dealing with the sand, you will only deal with a few important things; the bulk of the important things will not be dealt with. However, if you turn it around and first deal with the rocks, the important things, then you will get a lot done and will have to deal with only as much sand as you have space for.

This is what I see on a daily basis in workplaces around me—people spending all their time on sand and getting very few rocks into the jar. Most people feel that they know their priorities, they know what is important. However, they mistakenly assume that just because they know what is important, they are actually prioritizing it and dealing with it. That is a myth. It is more likely that you know what is important, what your rocks are, but the bulk of your time and energy is still spent on the sand.

To make sure people understand, I often do an exercise with them. On one sheet of paper, I make them write what they think is important, things which, if they did them well, would create learning, lead to career success and make them feel productive. Once they have written this on a sheet of paper, we fold it away, not to be opened till later. Then I ask them what all they did the previous month—which activities they did, where they spent their time, energy and money/resources and where they got their teams to spend their time/money/resources. It’s a detailed exercise. After that, based on where they spent their time/energy/resources, we try and write down which of these could have been important. If time/energy/resources were spent on them, then these would have been considered important, so in a way, we retrospectively derive what would have been important. This list of ‘derived important’ things is then written on another sheet of paper.

Then comes the most interesting part. We compare the two sheets of paper—the first sheet, what people thought was important to them, and the second list, the derived important things. I am sure you are not surprised when I say that in most cases, there is very little in common between the two lists. This is the greatest tragedy of productivity—that most people do not actually spend their time/energy/resources on what they think is important to them. This is true of life in general, but let us focus here on work. At work, people know what is important, they know that focusing on the important things will produce results, get them success, create value and learning and sharpen their algorithms. The tragedy is that despite knowing that, most people do not spend their time/energy/resources at work on those things, and hence never achieve the success they are capable of.

In my own professional journey, I know I was blessed to have an in-built God-given TMRR model, which kept sharpening my algorithm. It is my privilege and my blessing to have been born with that. But despite that, for a fair share of my career, I knew I was not producing the kind of impact I could, the kind of value I was capable of. And then one day, the bolt from my TMRR struck. I reflected and realized the reason for it—it was the sand and rocks disease. I knew what the important things were, but I did not have a process to ensure that I spent my time/energy/resources on these things. My time was being consumed by the sand first. That is when I came up with the second approach I have been following to manage my productivity, the method of allocating time to the ‘rocks first’.

It is a very simple approach I have been following for many years now. At the beginning of each month, I make a list of important things, things I consider priorities. I force myself to order this as well, putting the most important ones at the top. Most times, this list is not very different from the list of the previous month, and that is how it should be; priorities should not change often. But I do make this list each month. Then I start by allocating time in my calendar for the next month, starting with the most important things at the top. Once I have given as much time as the top item requires, I move to the next item, and so on. I keep moving down my priority list till I have allocated 85 per cent of the time I have for the next month. The balance 15 per cent is what I leave for the unavoidable sand that all of us have to deal with. This 85 per cent is formalized, it is in my calendar, and I have developed the discipline to never compromise on this. I never allow the sand to replace one of the rocks. This approach of a formal ‘calendared’ allocation of time at work, to what I consider the rocks, has been among the greatest productivity unlocks of my work life.

This also had some interesting unintended benefits. It significantly improved my delegation. It became very simple for me—if it was not one of the rocks I had time for, if it was not in my calendar with allocated time, then I didn’t need to do it myself. Every such thing is delegable and one of my team members can do it. I delegated a great deal and ensured that I got out of the way of my team in such things. ‘You decide, you do it, it is not in my calendar, it is not a rock for me’ was my mantra. And that delegation freed me and at the same time energized my team. They had a set of things they could do with complete freedom, without worrying that the boss was constantly breathing down their necks.

My assertion to each one of you is that too much of your time is being spent managing the sand. It is a myth to assume that because you know what the rocks are, you are spending your time, energy and money on these. It does not happen by itself; you need to catalyse the process of ensuring that you are actually focusing on the rocks. I told you what my method is. It is simple, and you can follow it as well. Equally, you can find your own method. Either way, make sure that you are catalysing the attention to the rocks. Left to itself, it is always the sand that flows into the jar first.

So these are my two methods to higher productivity—the circle of influence approach and the ‘rocks first’ approach. Despite these approaches, I wouldn’t say I am at my productive best all the time; it is a very difficult thing to be. But again, thanks to my TMRR, I have figured out how to recognize when I am not at my productive best. I have learnt that the symptom to look out for is the feeling of frustration. Frustration happens when you feel you are doing your best and yet things are not moving ahead. Then I go back and analyse why. I assess whether the circle of concern is taking up too much of my focus. I go back and check whether I am spending my time/energy/resources on the rocks. Typically, the problem would be in one of these areas, and once I correct it, I can sense my productivity come back up fairly quickly. I would urge each one of you also to try and recognize the symptoms for yourself when you are in a low productivity phase. Recognize the symptoms and fix the problem soon. I would be willing to place a wager that whenever you feel frustrated, if you stop and analyse why, there is a very high probability that you are in your circle of concern. Time and energy that is gone can never come back. Be at your productive best for as much of your work life as possible as it is crucial for your success.

Unleash the Catalyst

- To be successful, to generate real individual growth, just developing your experience algorithm is not enough. You have to employ that algorithm in a highly productive way. Your productivity is the means by which you convert your experience algorithm into value and results for yourself and your organization.

- The higher you go in the corporate ladder, the more the need to grow your productivity. And your productivity does not increase by itself; it has to be catalysed to grow.

- The catalysts I have used in my work life for my productivity are:

- Relentless focus on the circle of influence and avoiding like a plague what is in the circle of concern.

- Having a disciplined ‘rocks first’ time-allocation system, where I ensure that I provide my time/energy for the rocks and not the sand.

- If you’d like to, you can use my methods. If not, you can develop your own. Whatever be the method, please do not ignore your productivity.

Unleashing the Catalyst: Summarizing Part I and Setting Up Part II

In Part I, we have covered the means to driving real individual growth in three important concepts:

- Converting time into experience is the very bedrock of real individual growth. An effective TMRR model is the key to converting the time you are spending at work into an experience algorithm that will drive your success in the future.

- Applying the TMRR algorithm on major learning cycles is an exponential way to drive real individual growth.

- Just building the experience algorithm is not enough. You have to parallelly grow your productivity. Productivity is the means through which you can convert the experience algorithm into results. The key to growing productivity is to focus on the circle of influence and to make sure you allocate your time to the rocks and not the sand.

However, real individual growth has to be backed by good career management. I have often seen individuals with fantastic experience algorithms and productivity being tripped up by poor career decisions which they then struggle to recover from. We are very much in a VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity) world, including in how careers develop and how they are managed. It is important to have the right approach to managing your career, to make the right career decisions, if you want to convert your real individual growth into long-term career success. And the beauty is, the principle remains the same—focus on the deeds and the results will come. Focus on real individual growth, which is the driver of career success, and that career success will be yours.

The next section, Part II, is about career management. It is about helping you understand how to make career decisions while focusing on real individual growth.