12

The Twin Hs: The Key Catalysts for Leadership Impact

The first value I want to talk about is honesty, often also referred to as integrity. I like the simpler and broader term honesty, so let us use that for this chapter. I have no doubt in my mind that pristine honesty is an extraordinary driver of leadership impact. It is the one value which, if embraced in its truest form, will give you immense, loyal followership and influence. The challenge with honesty is, how does one set the standard for honesty, pristine honesty at that? In my fifty years, I have met possibly hundreds of thousands of people. I am yet to meet even one person who believes that they are dishonest. Each one of us believes that we are honest. The reason for that is that there is no set standard for it. There is no specification or control standard that says this is the level above which you are an honest person and below which you are dishonest. Hence, each one of us feels we are honest, not because of our absolute level of honesty, but because we always set the standard lower than our current personal honesty level.

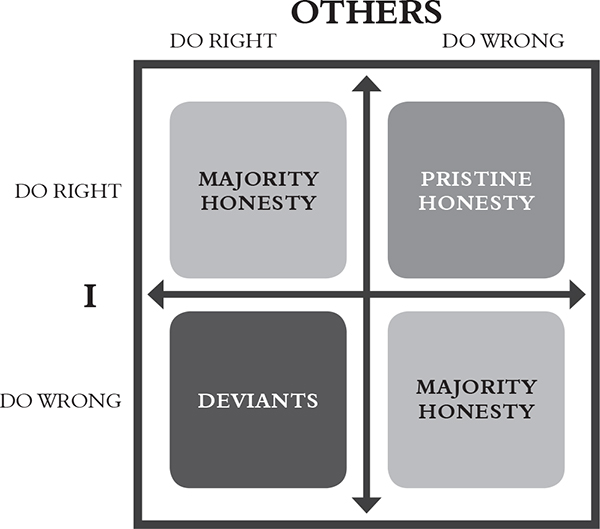

If you want to set a high benchmark for values, with honesty as your core lodestar value, then the starting point has to be defining a standard of honesty for yourself. Let me try and do that for you with the help of the diagram below.

As you can see in that diagram, on the Y axis is ‘I’ and there are two boxes—‘I do right’ and ‘I do wrong’. On the X axis is ‘others’, and there are two boxes—‘others do right’ and ‘others do wrong’.

We will use this diagram to understand our current standard of honesty and then try and see how we can set a new standard for ourselves.

The quadrant of ‘I do wrong’, even when ‘others do right’, is what I like to call the quadrant of ‘deviants’. This is the small minority of the population who does wrong even when everybody else is doing right. They are the criminals, the frauds, the harassers, the embezzlers, etc. They are a small minority. I hope God will bless them and reform them. I am sure none of you fall into that quadrant of deviants.

Most of us fall into the two quadrants of what I call ‘majority honesty’, which is we do right when everybody else does right, but we find it acceptable to do wrong when everybody else does wrong. Nothing typifies this better than our behaviour at traffic signals on Indian roads. At a traffic signal, right and wrong are determined by the signal, not by others. If the signal is red, you stop, and if it’s green, you go. But what is our behaviour there really driven by? If the signal is red and everybody else has stopped, we stop. But if the signal is red and others are not stopping, what do we do? Do we stop because it is the right thing to do when the signal is red? No, we don’t, most of the time. If everybody else is ignoring the signal, we ignore it too. In effect, we find it easy to do wrong because everybody else is also doing wrong. And when we do wrong that way, we don’t think we are dishonest; we think it is acceptable for honest people to do wrong because everybody else is doing wrong as well. That does not make us dishonest in our own eyes.

Even our Indian biological constitution is that way. When I am on the streets of Mumbai and I feel spit rising to my mouth, then my biological constitution is such that I cannot keep that spit in my mouth—it must come out on to the streets of Mumbai. And then one day, I take a five-hour flight to Singapore. I land in the pristine, clean city, and suddenly, my body changes. The spit in my mouth refuses to come out on to the streets of Singapore. Despite years of spitting in Mumbai, just one five-hour flight can change how my spit behaves.

Apologies for the sarcasm in the para above, but as you can see, I want to drive home the concept of majority honesty. We find it acceptable to spit on Mumbai streets because everybody else is doing it. But the moment we land in Singapore, where others are not spitting, we suddenly feel it’s wrong to spit on the streets. And then after a week, another five-hour return flight to Mumbai and majority honesty kicks in. Suddenly, spitting on the street is acceptable again. Spitting, in the above anecdote, is simply an example to explain the concept. It applies to all those things like not standing in a line, giving or taking bribes, leaving toilets dirty, etc., which we do just because everybody else does them too.

The basic construct of majority honesty is that what we use as the standard of honesty, the standard to determine what is right and wrong, is not our own judgement, our own moral compass. Instead, it is based on what the majority does, and if the majority gets away with doing something wrong, then doing wrong becomes honesty for us too.

Hence, if we want to be truly honest, to be considered someone with high integrity, to be among the small percentage of population that can truly stand up and say ‘I am genuinely honest’, then we have to change our standard of honesty. If you truly want to be honest, then you must have the courage to do right even when everybody else does wrong. You must move to the quadrant of pristine honesty. The quadrant of pristine honesty is when I do right, even when others do wrong.

The crucial change required to move to the pristine honesty quadrant is changing the reference standard of what is honest—from ‘what the majority does’ to ‘what I think is right’. It is an easy change to describe in words, a difficult one to execute in life. Let me give you a simple example from my own life. When I joined a new company, there was an existing culture of all meetings starting late and ending late. In the early days, I also fell into that trap of being late to meetings. Basically, I was doing what others did—I had allowed my standard to change from what is right to what others were doing. Then one fine day, the realization dawned. I realized that despite all my preaching on honesty, I was not practising it on the simplest of things like being on time for meetings, even if others were not. Then I reoriented myself to saying I will do what I think is right, which is to be on time for meetings, even if others are late. It is a simple example to demonstrate that pristine honesty is a difficult thing to practise. Every now and then, there is a temptation to lapse into ‘since others do wrong, it is acceptable for me also to do wrong’. You have to constantly remind yourself and focus on doing what you think is right and take a decision that you will not do anything wrong simply because everyone else does it.

The impact of pristine honesty as a catalyst on greater leadership impact is extraordinary. Truly great leaders have often been inflexibly obdurate on what they believe is right, even against tremendous popular sentiment. Going back to Gandhiji, the number of times he stood firm in his beliefs, even when the entire population stood against him, is well-documented. There were times he went on a fast to death because he believed the entire population was doing something wrong and he was willing to stake his life on what he thought was right, even if it was against popular sentiment.

The story is the same in the corporate world. Truly great leaders have stood for what they believe is right, even against popular sentiment in their companies. This pristine honesty and integrity, over time, is what has given them the leadership impact, the extraordinary followership and influence, which very few corporate leaders are ever able to build. Most corporate leaders are not able to successfully build leadership impact based on their values beyond the leadership impact created by their position. You have that choice—do you want to be among the many leaders who are primarily governed by popular opinion or do you want to be among the few leaders who are governed by what they believe is right? If you want to be among the very few leaders who are larger than life, who are beyond the chair and the position they occupy, and who are legacy-creating, then you have to catalyse your leadership with the power of pristine honesty.

The Other H, Humility

The second value I want to talk about is the other H, humility. I want to describe this value from my own context to start with. I believe I am reasonably successful in my work life. I have operated at several senior positions and created impact. When you get to senior levels in the corporate world, you do kind of get a demi-god status, and people in the company might often flatter you. It is possible to allow this to go to your head and for you to start thinking that you are indeed extraordinary. I have always desperately tried to remind myself that I am just another person. I just happen to be successful in my career and that does not make me God. I try not to fly too high and always keep my feet on the ground. And talking of feet, I want to tell you the story about my feet and legs.

I was born with a severe deformity. All of us have our knees in front of our legs. When I was born, the knee on my left leg was on the back side of my leg. My family used to say that it was because I bent my left leg at the knee such that my feet moved in the direction of my chest when I was born. It was but obvious that with that kind of deformity, I would possibly never be able to walk in my life.

Now, this was in the late 1960s in Chennai. Within a very short time, my family took me to most orthopaedics in the city. None of the doctors had seen many cases like mine and there was no clear solution in sight. My family was of limited means, and they could not afford to fly me to a different city or country to assess the situation and seek treatment.

I had an extraordinary grandmother, a lady who never went to school, got married at fourteen and had five kids by the age of twenty-two, with my mother being her eldest. I have no doubt that if she were born in the modern era, with more equal opportunities for both genders, she would have at the very least headed a country—truly a courageous lady with great capacity for decision-making and consensus-building. She, along with my parents, was faced with the decision on what to do with me in this situation, where no doctor was willing to assure complete success of the treatment. They had to make two decisions—one, whether they should take the risk of a very complex treatment on a newborn for which there was no guarantee of success and, two, which doctor to go to, since none of the doctors promised success. Everybody gave them probabilities.

They took both decisions. They took the first decision of going ahead with the treatment. The logic was simple, they said, let us give the boy a chance. In the worst case scenario, a failed treatment, the risk to life was minimal, and so it simply meant that I lived with the deformity my whole life, which would have been the case anyway if they did not do anything. In hindsight, an easy, obvious decision, but it took tremendous courage and foresight from my family to make it under those difficult, stressful circumstances. The second decision was which doctor to go to—again, not an easy decision to make. Each had their own approach to that situation and again, my family made the right choice (I shall not reveal the name of the doctor for privacy reasons, but I remain ever grateful to that person for my life).

The doctor did a great job. My family tells me I was flat on the bed for more than a year. I did not start walking, like most kids, before the age of two; there are many versions to when I started walking, but most of them agree that I took my first step not before the age of three. My earliest memories are of having a very large metallic contraption on my left leg, from my hip to my foot, with which I would go to school in the beginning. But life moved on and I could soon walk normally.

In my thirties, I started tasting success in my work life. One day, my grandmother sat me down. She said, I am so proud of you for being successful, but never forget why you are here. You are here because Dr X had the skill to successfully carry out a difficult treatment many decades ago. He could do it in an era when neither the technology nor the resources for such a complex procedure was available. His skill and the prayers of the family are why you are here, why you are what you are. I still remember that day, and the way she said it hit me. I was facing the first flush of success in my career, starting to fly a bit, starting to think I am Superman. That day, I landed on my feet, on those feet which were deformed when I was born and then corrected, thanks to the decisions my family took and to the skill of the doctor. Ever since then, I have stayed on my feet, no matter how successful I have been.

When I was in my early forties, I ran my first half-marathon. I covered 21 km in 2 hours and 52 minutes. Not great by any athletic standards, but given how I was born, possibly a small miracle that I could run at all. After I had crossed the finish line, I called my grandmother and told her what I had managed to do, and she cried on the phone that day. And true to her style, again told me, never forget why you are able to run, never forget why you are able to lead the life you are living.

It’s indeed the truth—my success in life can be attributed to the decisions my family took and to the skill of the doctor. If my family had got its decisions wrong or if the doctor had got something wrong, I would probably never have walked. It might have meant I never went to school, never got educated, never worked, never became successful in my career and never wrote this book either. Yet, when I was successful, it would have been easy for me to forget this and start to think the reason for my success was what I had done, to lose my humility and to think I and I alone made it happen.

In the corporate world, quite often, one does come across people who change a lot with success, who lose touch with humility, with themselves, and start to function a few feet off the ground in their minds.

One of my favourite quotes is, ‘You are not as good as your best success; you are not as bad as your worst failure.’ We are clearly in a highly VUCA-filled world, where success and failure both happen at a fair pace. The best of companies and the best of leaders experience them. Failure, especially, seems to rear its head when there is much success, when you start to think nothing can go wrong, when you lose touch with humility.

Humility is the value that I believe grounds people. It is this value that allows you to be centred and not fly off when you experience success. If you are humble, you know that no success is ever created by you alone; there are other people involved, there are circumstances that contributed to your success, and so on. Humility allows you to enjoy the success without letting it affect you, without it creating arrogance in you. Equally, the grounded nature of a humble person is what also allows him or her to deal with failure when it happens. If you are humble, your ability to stay grounded through cycles of success and failure is much higher, and your ability to sustain long-term success is much higher as well.

Humility has a tremendous impact on leadership and in creating followership. Often, powerful leaders are those who have a very ambitious vision, but have the humility to not let that ambitious vision make them arrogant. Such people create a sense of ‘cause’ in their teams and organizations because their humility is what assures people that the leader is chasing the ambition not for his or her personal gain, but because it is the right thing to do, because they believe in it. When there is a powerful vision and a leader who, because of their humility, is seen to be chasing that vision for unselfish reasons, then that combination is effective in creating leadership impact.