“On my first day at a hearing school, having transferred from a deaf school, my mother asked if I was excited to meet my new tee-ser (teacher). I asked, “But what about Julie, won’t she want a new sister too?”

—Marla

In the early 1960s, hope and optimism towards being deaf were widespread in the DEAF-WORLD. However, resistance was led by predominantly hearing administrators, who set Department of Education and governmental policies, promulgated communication philosophies, and were the key leaders of deaf education in every state. Simultaneously, based on work of William Stokoe, among several pioneers in the field of ASL, linguists affirmed ASL was an organic language with its own defined grammar and syntax. The response by hearing policy makers was minimal and did not take hold for most deaf children. Many family attitudes, behaviors, or levels of respect for ASL remained immutable and oral communication dominated, despite the pleas of deaf family members and the larger deaf adult community. These policies and eventually a host of federal laws were limited to providing access to educational programs as opposed to the foundation of family relationships which are based on human interactions.

The 1970s brought profound changes in response to the segregation of families and disabled children. In 1972, Congress passed Public Law 94–142, requiring public schools to provide education for all handicapped (as they were labeled back then) children. Further expansion of the Public Law 94–142 legislative renewal was the “Individuals with Disabilities Education Act” (IDEA) in 1990, which drew up specific provisions for local school districts to place each child in the “least restrictive environment” (LRE). School districts became responsible for accepting children with disabilities and for providing support services. This provision had great appeal to parents who wanted their children at or near home. Opponents of LRE challenged the law, arguing deaf residential schools were the places where an ASL environment existed, fostering language acquisition. They noted academic and social skills were nurtured through direct communication with peers and personnel staff, where deaf adult role models were rarely seen. They insisted that the deaf residential schools have historically been and should be kept as the LRE (Lane and Hoffmeister and Bahan 1996). In 2001, a federal law, No Child Left Behind, (NCLB) was added with the goal to close “the achievement gap with accountability, flexibility, and choice, so that no child is left behind” (No Child Left Behind Act of 2001). Nevertheless, as a result of these laws, deaf children made an exodus to mainstream programs in the public schools. Additional services were provided: itinerant teachers, classroom note takers, Sign or oral interpreters, and teachers’ aides. Mainstreaming had its appeal because the educators and families were astonished and appalled to learn deaf children’s literacy levels in the deaf residential schools were lower than those of their hearing peers.

During Individual Education Plan (IEP) meetings, school psychologists, therapists and educators would report the results of their assessments to determine the appropriate academic placement for a deaf student. However, historically these instruments were not standardized or designed to assess deaf children, yet they determined how and where deaf children would be educated—with little regard for whether the child had fluency in a language—whether it was ASL, English or whatever might have been used in the home. Among many reasons for the failure, according to various researchers on literacy of deaf children, are the differing philosophies among the academicians about how deaf children should acquire the English language: use ASL, Sign with speech simultaneously, and/or use speech only. The requirement for state certification to become an educator of the deaf did not and still in many states does not include proficiency in ASL. In the twenty-first century, two researchers, Jenny Singleton and Dianne Morgan, defined the optimal educational environment promoting an accessible language acquisition for deaf children within a classroom:

In this new conceptualization, an educator of the deaf creates an instructional context that aims to build visual attunement, emotional understanding and competence, proficiency in a natural signed language supported primarily through engagement in “everyday talk” and some explicit instruction, and competence in multiple modes of English that are accessible to a visually oriented learner. This immersion approach includes teacher modeling and structuring of the children’s development of linguistic and sociocultural competence in their worlds (both hearing and Deaf) [Singleton and Morgan 2006, 367].

Several deaf siblings who switched to mainstream programs expressed their regrets at not staying at the deaf school, where being deaf was not anything different but a readily accepted happenstance. Ongoing interaction and communication were valued.

In the late 1980s, Oliver Sacks, a scholar on disability subjects, warned of the potential dangers when considering placement of deaf children:

Mainstreaming—educating deaf children with the non-deaf—has the advantage of introducing the deaf to others, the world-at-large (at least, this is the supposition); but it may also introduce an isolation of its own and serve to cut the deaf off from their own language and culture [Sacks 1989, 136].

Most of the deaf siblings interviewed, like Gina A. Oliva in her book Alone in the Mainstream, detailed how being the only deaf student among many hearing students did not make up for the ease of communication and socialization in a deaf residential environment with deaf peers, teachers, staff, administrators, and other employees (Oliva 2004).

Justin, married with two deaf children, switched from a mainstream to a residential deaf school, and reminisced on the power of learning through social interaction:

One thing that’s often emphasized in a deaf school is learning by osmosis. Suppose the two of us are friends, I’m interested in football and you’re interested in baseball. So you talk about baseball to me and I learn from you. I talk about football to you and my dad tells me about football and I teach you what my dad taught me. Now with hearing kids in hearing school, suppose there are two kids talking about basketball. Each often over-hears other classmates’ conversations, learning more about basketball. A deaf kid typically wouldn’t catch casual conversations among hearing classmates going on around them. The evolution of knowledge from one person to another person—I didn’t get that when I was in the mainstream school. I learned very little from my peers.

By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, these laws have succeeded in integrating eighty-five percent of deaf children into mainstream public schools (Marschark and Hauser 2012). As a result, several residential schools for the deaf closed and others were in danger of closing amidst decisions made by state level politicians and hearing administrators and policy makers who have minimal contact with the deaf community. If the primary concern among the lawmakers was the financial burden to society, then why are there so many deaf adult recipients of federal and state financial services?

… according to the Census Bureau’s 2010 American Community Survey, just over 48 percent of 18–64-year-olds who are deaf or hard of hearing were employed, Senator Harkin said, “None of us can be proud of the overall employment situation for people who are deaf and hard of hearing in this country” [Gallaudet University>Home>News>HELP Committee Public Hearing 2013].

These are the long-term consequences of not preparing deaf children for today’s society. How do policy makers respond to anguished parents who admit their deaf child struggles to succeed in a predominantly hearing environment with public school teachers who have little or no training to address deaf students’ needs?

Jaron couldn’t let go of his anger towards his parents for not realizing the impact of mainstreaming on his socialization skills, which he discovered, after meeting deaf teenagers, were essential to his welfare. He reminisced how limited his interaction were with his siblings. During his interview, he outlined a list of things he wished he had to avert the isolation:

1. Have an expert, a teacher of the deaf or deaf adults, either orally or in sign, who would sit down with me like a Big Sister [or] Big Brother

2. Send me to deaf camps, after school programs, or deaf events

3. For emotional support, have deaf teachers or counselors who sign to explain to me about the communication issues, socialization, [and] frustrations and advise me where to find deaf friends, not just a few, but a larger crowd.

He ended his wish list wondering: “Why am I the one who was in need for support services when my sibling didn’t go to ASL classes? I had no confidence in myself.”

Records have indicated how parents of deaf children navigated within the educational system through a system using IEPs as required by the No Child Left Behind legislation. The 2011 GAO Report reports the dismal academic results:

Although experts suggest that deaf and hard of hearing children who receive appropriate educational and other services can successfully transition to adulthood, research indicates that many do not receive the necessary support early on or during their school years to keep up with their hearing peers. For example, according to one study, the median reading comprehension score of deaf or hard of hearing students at age 18 was below the median of fourth grade hearing students [May 2011 Report of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children: Federal Support for Developing Language and Literacy 2011, 1].

Deaf children who leave school with minimal academic and social skills cannot be expected to be financially independent lacking the fundamental reading, writing and communication skills necessary to compete in today’s global job market.

Meanwhile, at home, their hearing siblings were not immune to what was happening around them. Gila described with sadness how her deaf sister struggled with academics: “She’s got a great imagination with Art as her muse but her English is very poor. She’s always not been a good ‘book learner.” Hearing siblings like her witness their parents’ agony and hear about their different sibling from others while their deaf siblings are the innocent pawns in parents,’ educators’ and society’s chess game, all expecting deaf children to take on the characteristics of hearing people. As a longtime staunch advocate of deaf people who are part of a culture and a linguistic minority, Harlan Lane challenged educators and families to define normalization in the family.

The deaf child or adult is not an ordinary dependent, as any hearing person might be who goes to a doctor, an audiologist, as psychologist. He is a stigmatized dependent. When isolated from others of his kind, the deaf child with hearing parents and a hearing school is bound to feel deviant. Why can’t he be like other people and conform to the demands made on him—most of all, the demand of facile communication in English [H. Lane 1999, 88]?

Parallel to educational legislation and the emerging ripple effect of ASL as a legitimate language, the next generation of experts appeared on the educational scene. They recommended using sign to communicate with young deaf children. However, instead of using ASL, educators and parents adopted a new philosophy called Total Communication. It was originally an approach advocating that parents use whatever means necessary to achieve effective communication and acquire language. In practice, it became a way for hearing parents and hearing educators to avoid learning a new language, ASL. One of the most popular methods for Total Communication was Simultaneous Communication (SimCom); it used the vocabulary of ASL married to the syntax of English, while simultaneously speaking English. Many educators believed SimCom would allow deaf children to see English on the hands and thereby improve their literacy. However, what the users of SimCom failed to recognize is that SimCom is not a language; ASL is.

The parents of the older deaf siblings (those born before 1970) enrolled their deaf children in residential or day schools using oral communication methods. In contrast, the parents of the younger siblings had an alphabet soup of mainstreaming and residential schools using all forms of “English on the Hands” known as Manually Coded English (MCE). By the early 1970s, professionals in the field of deaf education who created MCE systems had a common goal: to make the English visible to deaf children. Educators recognized that the longstanding use of oral communication methods was not resulting in literacy for many deaf children. As they further analyzed the challenges of lipreading inherent in oralism, they acknowledged that spoken English was not visually accessible to deaf children while engaged in conversations with hearing teachers, peers and family members.

As a response, these educators took the matter into their own hands to create visual communication systems. MCE systems entail an array of hand signals by borrowing vocabulary and the signed alphabet from ASL. Educators identified Signs to match English root words. Then, they invented specific hand signals for the to-be verbs, verb inflections, noun suffixes and pronouns, all placed together in English word order. Interestingly, the MCE systems differed from one another based on their assessment of those that preceded them. For example, Signing Essential English (SEE 1) later became Signing Exact English (SEE 2), then eventually became Signed English (SE); all were widely adopted by deaf education programs. Within the core of the deaf community, none of the MCE systems evolved naturally. MCE systems instead became popular among hearing parents and professionals (teachers, speech therapists, audiologists and interpreters). During this time, the majority of deaf children began attending day programs, often in separate classes within a neighborhood school. The younger deaf siblings attended these programs, lived at home with their families, and used MCE systems with their hearing siblings as well as with their parents. One of the selling points of MCE systems was the belief that it was easier to use the word order of English, a language their hearing parents and hearing siblings already knew, as opposed to learning the grammar of a different language.

If educators shifted their focus to creating alternative ways to acquire English, did it justify superimposing the features of a visual-spatial language (ASL) onto a linear language (English)? Since “ASL is a simultaneous language in which individual signs are amalgamated into composite ones; one complex, fluid movement” (Solomon 2012, 82), ASL incorporates the essence of the meaning where the relationship of ideas is interdependent. In contrast, in English, the word order of The train hit the car versus The car hit the train determines which vehicle hit and which vehicle was hit. MCE systems retain the concept that “English is a sequential language, with words produced in defined order; the listener’s short-term memory holds the words of a sentence, then takes meaning from their relationship” (Solomon 2012, 82). For example, MCE Signers would use the invented Sign for the followed by an ASL sign for train, a separate ASL sign for hit followed by another ASL sign for car. What’s the advantage of using an MCE system when ASL already offers equivalent meaning? In the early ’70s, recognition of ASL as a complete language was in its infancy, still defending its legitimacy. In those days, trainings, classes, workshops or even assessments for ASL were nonexistent.

Since linguists who have studied ASL over the last century have confirmed that ASL is not a linear language but instead is a visual-spatial language, ASL begins with the signing space as a key parameter coupled with specific handshapes for each signed word. For every word, the ASL user needs to ensure his palm orientation is correct (up, down, to one side or the other). The positioning of the ASL signs for accuracy, identifying the location (on the body, the face and/or in signing space) and the movement (fixed or moving in defined ways) are all essential to convey the meaning. Each parameter reveals by showing, rather than telling, how each ASL sign and concept is interdependent. Non-manual grammatical signals (NMGS), also known as facial expressions and mouth morphemes, are additional parameters since they define the language prosody (the stresses and intonations of each word/sign). In ASL, the same two sentences (“The train hit the car” and “The car hit the train”) would be conveyed spatially in ASL by setting up and positioning the ASL sign for train in one space, setting and positioning the ASL sign for car in another, and then moving the appropriate vehicle to show which one hit the other. Simultaneously, NMGS and mouth morphemes show the intensity of the distance and the hit.

As educators went down the path of using MCE systems, they discovered they needed a variety of additional tools to master the intricacies of the English language. Teaching deaf students multiple meanings of English words when ASL had separate vocabulary for each meaning continued to be their challenge. For example, Gerry Gustason, one of the founders of SEE 1, created a two-out-of-three rule determining which ASL vocabulary to use for these English words. In her example for the English word wind, where several meanings were to be considered: air in motion, or the turning of a stem on a watch, or the turning of rope to gather in a circular fashion, she applied the two-out-of-three rule. To decide which sign to use, the educator would have to first determine: Is the word spelled the same? (yes) Does the word sound the same? (no) And does the word mean the same thing? (no) Therefore, based on the only one criterion that the spelling was the same, they would borrow the two different ASL vocabulary words for SEE since ASL already had the different meanings for them to use.

The two-out-of three-rule says that if two of the questions are answered in the affirmative, one sign is used, as in the following example:

To bear a burden, bear a child or meet a bear, are all signed with the same basic sign for the word bear because spelling and sound are the same and only the meaning differs. Similarly only one sign for run is used whether the meaning is John is running, the water is running, or your nose is running or the man is running for office … the main reason for this was to represent on the hands what was said in English, so the students learned how a concept was represented in English [Gustason 1990, 116].

Regardless of her decision of which sign to use, the idea behind this tenet of SEE was to identify only the “signs to represent one English word each … English should be signed as it is spoken” (Gustason 1990, 115). These kinds of decisions were ridiculed by and saddened fluent ASL users, especially when they saw children from MCE programs Signing the equivalent of: “She saw a bare (bear) and her stocking ripped (ran) as fast as her legs wood (would) carry her.” Another feature of MCE systems was the addition of initialized Signs—the fingerspelled first letter of an English word added to the ASL vocabulary—to distinguish between English synonyms like demonstrate and example. To Sign the word example, instead of using the index finger handshape as used in ASL with the dominant hand, MCE substitutes the fingerspelled letter E. For demonstrate, the Signer substitutes the fingerspelled letter D. This feature of MCE systems has been adopted by the recent generations of mainstreamed children who have been exposed to them through interacting with their Sign language interpreters (many of whom learned MCE systems instead of ASL).

The MCE system’s founders had positive intentions—to distinguish English words using numerous different hand signals in order to improve deaf children’s English literacy—but in reality, the research data showed the results to be otherwise (Lane and Hoffmeister and Bahan 1996). The MCE systems were designed to be used while simultaneously speaking English. Genie Gertz, a deaf scholar, explains several reasons for the failure of Simultaneous Communication (SimCom):

A limited number of people are particularly skilled at talking and signing at the same time, but many other people are really not able to do it. They try to talk and sign at the same time and nothing clear comes out. As a result of using Simcom, many signs are dropped out. The sign also deteriorates significantly in its quality and intelligibility. Often, many Deaf people can’t understand what people are saying, and they have to work so much harder to try and receive the message. When people speak English, the ASL becomes unintelligible. SimCom is an incomprehensible mix of two different modalities…. The language issue with deaf children addresses the fact that the acquisition of a first language is very important. By trying to teach ASL and English, Simcom confuses deaf children further because, when some people sign and speak at the same time, they are ultimately doing neither correctly…. Simcom doesn’t work because ASL and English are two completely different languages. The underlying mechanism of Simcom requires the “speaking” part that imposes on Deaf people to use English, often for the convenience of hearing people. In this sense, SimCom disempowers Deaf people from using ASL to the full extent and consequently weakens them in development of their Deaf identity [Gertz 2008, 226–227].

SimCom eventually became the communication system in the home among many families as a result of the efforts of MCE professionals.

With ASL emerging as the preferred language by the deaf siblings interviewed, deaf and hearing siblings were left with a myriad of communication modalities. Darcy, who learned to Sign as a child, described how she communicates with her deaf brother:

When my mom learned how to Sign, she probably took Signed English classes, not ASL. Sadly, I still use Signed English with my brother. I try to incorporate ASL but I know I am very weak with ASL. Pretty much, with anyone else who’s deaf, my brother uses ASL. When he’s with me, it’s just force of habit for him to code switch from ASL to Signed English.

As adults, deaf siblings would code-switch by going back and forth between using ASL in the DEAF-WORLD and MCE systems with their family members. In addition, they adapt with deaf people who tend to use MCE systems. The act of code-switching, as this sibling describes, is indicative of those deaf and hearing siblings who are trapped by their communication patterns stemming from their childhood. Code-switching not only creates frustrations during conversations, causing many misunderstandings, it prevents both deaf and hearing siblings from becoming fluent in ASL as adults—a commodity both clearly see as being critical to bonding more closely with one another.

Parallel to the creation of MCE systems, other educators entered the fray in order to make the sounds of English words visible to deaf children, recognizing visual access was the key to effective communication. To achieve that goal, R. Orin Corbett developed a system to differentiate the sounds of English. Known as Cued Speech, it was described as “a visual mode of communication that uses handshapes and placements in combination with the mouth movements of speech to make the phonemes of a spoken language look different from each other” (Cued Speech n.d.). The uniqueness of Cued Speech was speech’s multiple sounds that look alike on the lips or spoken inside the mouth or behind the teeth, are differentiated by being nasal, using one’s breath or voiced. For example, a limited number of hand signals created would provide the cues to show the difference between mama, papa, and baby which look the same on the lips with their multiple syllables. To address the challenge with decoding during reading, writing and speech articulation, another tool was developed by the International Communications Learning Institute (ICLI) known as Visual Phonics in 1982. Its mission was to use tactile, kinesthetic and visual techniques to teach deaf children to “see the sound and internalize English phonemes and understand how they map onto English letters and words” (See the Sound n.d.).

Educators, speech therapists, audiologists and parents have seen some success using these phonetically based systems to teach deaf children speech, lipreading and pronunciation. However, the trade-off of the time spent doing these activities is the missed opportunities for ongoing engagement in conversations and fewer opportunities to develop critical thinking skills through reading, writing and comprehension. Sharing feelings, thoughts, and observations through interactions with family members, peers, and service providers is the foundation for any child’s language acquisition. In their earliest years, siblings are supposedly naturally engaged in this process, assisting and enabling their siblings to acquire a native language: every child’s birthright.

Research has shown that simultaneously mixing the ASL vocabulary with spoken English—like MCE systems—breaks the grammatical rules of both languages and muddies the speaker’s intention and meaning (Gertz 2008). Nevertheless, under the direction of predominantly hearing administrators and other educational staff members, every parent of the younger siblings used MCE or Cued Speech at home, rather than exclusively using speech. None of these siblings were raised using ASL, the only visual-gestural system affirmed by linguists to be a language. Children lived the consequences of the professional advice parents received about language choices, but also have been affected by their parents’ core attitudes to using ASL as opposed to using MCE systems. In spite of the history of Milan and its consequences, we asked the siblings, “How did you communicate with your parents and siblings as children and as adults?” All but one of the twenty-two deaf and hearing siblings interviewed followed parental communication patterns—whatever communication method they used as children, whether it was using speech or sign, they continued to use in their adult conversations. One exception was Risa, who used oral communication methods with her deaf brother while growing up, but as an adult, switched to Sign.

Laurel, an ASL interpreter, juggled between using both ASL and SimCom at home:

When the three of us are together, we typically use ASL. My mom uses English-like Signing and ASL. When it’s just the two of us (me and my mom), we SimCom. My mom did that because she thought that I would learn both languages, English and ASL. But she didn’t realize that when you SimCom, you’re splitting the languages. When I ask mom to do voice-off because I really want work on my ASL, she’d be willing but we slip into our comfort zone, Sim-Com, after a few minutes. And with my sister, it changes the dynamics whenever we use ASL.

The fallback to SimCom caused distress for the hearing sibling. She was keenly aware that each time her sister and mom were exposed to partial information either from lipreading, MCE or a phonetic system, their chances to be proficient in ASL diminished. When she studied ASL in her ASL Interpreting program, she learned for the first time the only way her sister and mom could be fully immersed in discussing complex topics effortlessly, including nuances, was for the three of them to use ASL exclusively. In addition, when siblings and other family members are constantly making adjustments and accommodations about which communication systems to use with one another, it interferes and distracts them from whatever they aimed to discuss, whether it’s to decide where to spend a vacation or what present to buy one another for their birthdays, seeing one another’s humor, sarcasms, hints, etc.—the very building blocks of their evolving relationship.

Since deaf and hearing siblings grew up under the Milan Impact, they bore the consequences of the edict banning ASL. Yet, conversations among siblings about ASL are a rarity. Most of the deaf and hearing siblings admitted they have not had heart-to-heart talks about ways to resolve their differences, largely a result of the limitations and frustrations, inherent in their communication using speech and MCE systems. Our research showed an underlying attitude toward ASL that continues to obstruct opportunities for sibling bonding. Conference workshops and retreats for families with deaf members, hosted by local and national organizations, are emerging with sibling peer support groups as essential components.

Based on the interviews, we created a series of vignettes of the non-signing hearing siblings and their deaf siblings as if they were in the same room. Although the interviews were conducted separately, these siblings were specifically vocal about ASL and its significance in the DEAF-WORLD. Since the adult deaf siblings have made a conscious decision to communicate in ASL, the scenarios propelled us to reframe perspectives of both deaf and hearing siblings. These vignettes uncover the non-signing siblings’ resistance to the change their deaf siblings had embraced.

Although they are related by blood, according to his sister Kacie, her brother’s discovery of ASL and the DEAF-WORLD is perceived to be the root of their conflict:

Our relationship is so negative part of me doesn’t want to learn ASL just to spite him. He’s been trying to ram it down our throats since he learned it himself, after he was out of the house. I have a busy life, working and trying to raise a family and quite honestly, I don’t see him enough nor do I want to. One positive thing though he’s brought sign to our lives and I find it extremely interesting that I would love to learn it…. I will not learn it for him…. Why should I? … he doesn’t deserve to have us take time out of our lives to learn a language that is his. He’s never tried to do anything that’s ours. You know, he was kind of forced to and resented it and then resented us. We can talk with one another, just like we did when we were kids. So why do I need to learn it? So, why doesn’t he make peace with that?

With the communication challenges, siblings have it within their power to embrace, resist or resent changes. What if Kacie’s learning ASL isn’t such a big deal? She is stating just because he’s changed doesn’t mean she had to when they understood one another perfectly. In our interview, her deaf brother Maxel had an answer:

I feel lost. It’s not just a one-time event; it is an on-going thing escalating over the years. Everyone talks, including me! It’s impossible to lipread when we’re socializing. Sign works. She is a stay-at-home mother and she has the time to learn if she wants to.

As an adult, using spoken English was Kacie’s choice. However, it was no longer Maxel’s. Yet as soon as Kacie said, “He’s never tried doing anything that is ours,” she realized they had been using her language to communicate with each other. Suddenly, there were no words to make amends. Every time he talks with Kacie, Maxel is exhausted from time-consuming and numerous repetitions to correct misunderstandings. He is telling her: “I have a solution to our communication difficulties and you are not interested!” Having different expectations about which language to use escalated their conflict. Kacie is comfortable communicating in spoken English, whereas Maxel finds ASL more effective. Another layer was the disagreement over priorities about making time for communication. Kacie resisted Maxel’s dictating her priorities by insisting she spend time learning ASL. However, Maxel does not have the luxury of time for constant missed opportunities for interaction and intimacy with his sibling. Arising from his determination to take advantage of the communication modality he’s discovered, ASL, from his perspective Kacie ought to seize the opportunity to use it to move their relationship in a positive direction. This has backfired.

The pitfalls involved in deaf-hearing sibling interactions are quite common and have rarely been discussed openly within families. Even if they identify the breakdowns in communication which are so emotionally charged, non-signing siblings and deaf siblings’ bonding becomes further complicated by society’s stigma attached to having a deaf sibling, for being a deaf sibling, and for being seen using a language of the hands in public. During the time Maxel and Kacie were growing up, Paul Higgins in Outsiders in a Hearing World: A Sociology of Deafness stressed the acceptance of ASL as the bridge to making the DEAF-WORLD more accommodating to those who are non-signing hearing siblings:

As children and as adults, the members of the deaf community experience frustration and embarrassment, when navigating in a hearing world. However, within the deaf community, easy and “natural” communication is usually taken for granted. In the hearing world it is rarely achieved. Within the deaf community there is no shame in being deaf. Within the hearing world the deaf were often made to feel ashamed until they grew more accustomed to the shaming behavior of the hearing. The deaf community is, then, partially a response to the unsatisfying interaction which the deaf experience in a hearing world [Higgins 1980, 170].

Was there any inkling that learning ASL and about the DEAF-WORLD would have any positive effect on Kacie and Maxel’s relationship? Outsiders are often intrigued with ASL, seeing it as an art form like dance, and often say, “It’s beautiful.” For Maxel, it has a different meaning. Yet Kacie sees how ASL can make a difference when she offers the suggestion that the next generation might give hope in bringing the siblings closer.

Yes, if anything positive has come out of it, it’s been my awareness, my friends, my family’s awareness of the DEAF-WORLD, and sensitivity to it…. I know that some hearing siblings have chosen to embrace their deaf sibling’s world and make it their lives, their professions…. My daughter who hears, obviously, hopefully will learn some ASL from him, which I never did; that might be a positive step towards my brother and I having some sort of a relationship.

Even though Kacie is intrigued with the idea of her daughter learning ASL from her brother, Kacie still refuses to acknowledge she is the one who needs ASL to communicate with her brother.

Many hearing siblings have never learned ASL. Warren as an adult saw the possible benefits but fell short of achieving them when he told his sister: “I know you would have preferred that I were fluent in ASL—that would have been helpful. I did try lessons and later gave up on it. My sense is that would have improved our relationship.”

Even when siblings mutually agree on the value of learning ASL and being part of the DEAF-WORLD, what other barriers continue to propel non-signing siblings from getting closer to their deaf siblings?

What I remember most about growing up with a deaf sibling is learning early on to have compassion for individuals with challenges. Most kids are not born with that trait and having a deaf sister taught me empathy at a very early age. Also I was able to witness firsthand other children learning that lesson.

In the above quote, Julie, Marla’s sister, knew of many challenges her deaf sister faced interacting with hearing family members including herself. Although her experiences have shaped her sensitivity, she has compartmentalized two perspectives: Her awareness of deaf people’s challenges and not learning to sign. Although she expresses compassion as an observer, recognizing ASL is as vital to deaf people as spoken English is to her, in her interactions with her deaf sibling, the invisible curtain of ”no ASL” is always present.

She was not alone in her response, even among those who describe their relationship with their deaf sibling as close, like Stefan:

Let me tell you all something! Unlike Kacie, I have a good relationship with my deaf sister; we spend the holidays together and other family celebrations. We used our TTYs to stay in touch, but now she prefers using the Video Relay Service (VRS) to call me, using an interpreter, so she can use ASL because she’s more expressive using ASL than English. But when we are facing each other, we do just fine. We both know it would have been easier if I knew ASL, but I don’t, and we’re OK with that. To be honest, I know my sister was always disappointed I didn’t learn to sign, I never felt we had to.

Stefan’s rationale for never having learned ASL echoes many of the non-signing siblings who were left with a lingering feeling as adults that ASL was a valuable commodity that would add more substance and depth to their sibling bond. Yet, these hearing siblings are frozen in their Oral communication, unable to break the pattern established as children.

David Luterman, a researcher who interviewed hearing teenagers and young adults with deaf siblings, quoted one as saying:

Robert prefers to sign now and doesn’t associate with hearing people if he can help it…. I wish we knew how to sign then and be able to interpret for him so he could understand while the show was on … he would have been more involved and would have known what was going on. But I realize that is a big issue that probably never will be solved [Luterman and Ross 1991, 52].

Siblings like Stefan and Robert believe it is too late and too complicated to learn ASL. As children, ongoing disputes, histories of bitterness, distrust and stubbornness may have gotten in the way of confronting these beliefs.

Other underlying factors affecting adult siblings’ relationships stem from the communication patterns parents use to resolve conflicts among themselves and with their children. These patterns could range from dictatorship style to consensus building. More often than not, siblings’ differences about how to communicate are rarely resolved. Instead they pile up in the hope that somehow things will eventually blow over. They don’t. Some non-signing siblings, based on their firsthand experiences, later realize the profound and damaging effects of their deaf siblings’ exclusion from surrounding chatter and strongly advocated early exposure to ASL for the next generation. Stefan’s deaf sister Joy, reminiscing on her childhood, reveals their older sister’s recognition of the impact of ASL:

Yes, I was disappointed but it never bothered me because I thought I was good in lipreading and had good speech. But sometimes, I didn’t understand my brother although my siblings understood me. They weren’t against me using sign with my friends in front of them but many of my friends’ parents were against signing. Now, it is impossible for my siblings to learn to sign. They just can’t! But my sister strongly encouraged me to teach her grandchildren ASL. I realized now it was important for them to learn ASL because I missed out on so much in my life.

The urge to reconcile represents a powerful feeling of optimism. If siblings come to an agreement about what they want out of their relationship, they are fortunate if the days, months or years they have left allow them to make up for whatever they lost. Time is neither their enemy nor their friend; it is the accumulation of little things over time that will heal each and therefore, one another.

When non-signing siblings, accustomed to their childhood communication patterns, experience the communication changes set by their deaf siblings, many still feel resistant, resulting in deeper wounds.

I guess my brother Greg would love to have me to learn to sign; he totally lives in a deaf environment now, and it’s where he feels the most comfortable. But when we were growing up, he spoke, and we used lipreading and cued speech. Whenever we spend time together, we communicate just fine. When it’s just the two of us, we’ll play sports and things where we don’t need to talk much. And I do know how to fingerspell. So if he missed lipreading something I say, I spell it and we move on. Like this, for example, I D-O-N-T W-A-N-T T-O B-E H-E-R-E. I’m sure he’d prefer I learn to sign in addition to fingerspelling but it’s not a major bone of contention between us, like Kacie has described with her sibling.

The fine thread linking the brothers is Avery’s use of fingerspelling and Cued Speech, which function as survival tools anytime speechreading and lipreading break down. Their time together centered on physical activities or games requiring minimal verbal interaction. It would preclude, for example, a heated discussion strategizing about which team might win the Super Bowl. Although Avery supplements his spoken English with fingerspelling rather than learning to sign, their limited communication tools thwart their brotherly bonding, interfering with the natural give-and-take of their interactions. Ongoing dialogues, without communication breakdowns, would bring the siblings a step closer to getting to know one another’s opinions, beliefs and reasons behind their thoughts, instead of adopting those of others, like their parents or those in authority positions. As deaf adults matured and immersed themselves in the DEAF-WORLD experiencing everyday interactions, they expressed a yearning for stronger bonds with their hearing siblings, wanting to know more about them as people, as parents, about their jobs; searching for detailed information surrounding their siblings’ lives.

Illustrating another barrier to sibling intimacy, one of the non-signers told of a specific misgiving about learning and using ASL. It was almost as if she was at a tipping point that could be a life changer:

Hmmm. I have a somewhat different perspective. I definitely acknowledge ASL has become an important part of my deaf brother’s life but at the same time, it has become a wall between us. I have a feeling if I did learn it, then it would become my responsibility to make sure he knows what’s going on and that takes away from me. I think he feels my not learning ASL means I don’t love him and … that’s far from the truth. It’s nothing personal against him but … my interests are elsewhere right now. I do love him and have tried to watch out for him throughout our lives.

Violet, the youngest sibling, was described by her deaf brother, Grant, as the most sensitive one in the family. These two siblings agreed she was his caretaker, a responsibility she took on as a young child. A professor of deaf education, Barbara Luetke-Stahlman, recounts one parent’s observations of the siblings’ role: “We don’t insist that they [the siblings] interpret, but we often discuss how important it is to include Mary Pat in the conversations around her. They are sensitive to her feelings of being left out” (Luetke-Stahlman 1992, 11).

Parents set the expectations for how siblings are to care for one another. Sometimes, children naturally slip into specific roles which parents reward with positive reinforcements. However, unexpected repercussions occur when siblings take on caretaking roles. In Violet’s case, Dale Atkins, a psychologist, explains the reasoning behind a caretaker role: “Hearing siblings commonly perceive that they have more responsibilities than their counterparts in caretaking activities for their hearing-impaired sibling…. They worry about giving their hearing-impaired sibling what they are missing, so they interpret for them” (Atkins 1987, 40).

Each time Grant mingles with non-signing hearing relatives or family friends, he is Violet’s helpless older brother. As much as he appreciates Violet’s efforts to include him, knowing she tried her best, he says it just never works: “I felt I am not important, brushed aside, off in a corner. Once in a while my sister would look at me and point out which relative was talking and try to summarize the conversation, but they’d forget to include me.”

The drama between siblings like Grant and Violet continues over many years, building a wall between them. As time passes and siblings’ roles evolve from caring for someone to being cared for, their unresolved tensions get thicker. The issue isn’t just between the siblings; it becomes the entire family’s issue. Their interaction has consequences: Violet was astute enough to recognize if she had been the only family member who knew ASL, her chances of being trapped with expanding her caretaking role would be greater. Non-signing family members and her deaf brother would come to expect her to facilitate their interactions. Involving the non-signing family members in discussions surrounding communication access could potentially ease the tensions between the siblings.

In retrospect, when deaf siblings described their non-signing hearing siblings’ efforts to reduce their isolation, they saw potential allies anticipating they would become close. However, Enid, one of the non-signing siblings, expressed her increased despair at her sister’s finding an ally outside of the family:

I’m with you, Violet! I haven’t learned ASL though I’ve met people who’ve seemed to pick it up so easily, I’m green with envy! I too have worked hard to include my sister by trying to tell her what people have said and have nagged my siblings to include her, and much as I’d love to know ASL, I can’t seem to find the time to do it. Even hanging out with her and her friends hasn’t motivated me to pursue it. I know she wants me to learn it; it’s connected with respect for her and her language, but I haven’t figured out how to fit it into my busy life what with family and work commitments. And I do think ASL is a beautiful language. My sister considers her deaf friends to be her family, whereas we, her blood family, are second rate because we don’t know or use ASL.

The ramifications of the deaf siblings searching for intimate relationships outside of the family have a tremendous effect on deaf and hearing siblings’ well-being. There is juxtaposition: I am included yet I am also excluded. Deaf siblings find deaf peers in the DEAF-WORLD as natural substitutes for developing close relationships. However, by doing so, they increase the risk that they will be apathetic towards getting closer to their sibling.

Hearing siblings feel the sting of the deaf sibling’s rejection, but Enid’s deaf sister Micki defends ASL as her lifeline: “Yes, I do struggle to understand my hearing siblings. When they make the effort to talk to me, I nod, pretending to understand but I’m nodding while grasping bits here and there, guessing what they’re saying, often asking them to repeat.”

Some siblings perceive learning ASL as a tool they chose not to use. However, Risa’s younger sister, an ASL interpreter, was the inspiration for giving her a brother she longed for:

I learned to Sign after I left home. During our growing up years, my brother and I struggled with speech and lipreading. I know it stifled and inhibited our interactions. After I learned to Sign, I was able to develop a close and comfortable relationship with my brother. Sign puts us on an equal footing where theoretically neither of us has to struggle. Although I have to admit since ASL is a second language for me, I’m always struggling to express myself in it, but I think less than he would be struggling to lipread me.

As siblings like Risa who saw ASL as a necessity for building a relationship with her deaf brother, deaf and hearing siblings have the power to let go of their past and recognize they do not have to live by their childhood histories and patterns.

Since ASL and the DEAF-WORLD are inseparable, French linguist Francois Grosjean highlights the kinship:

Both as an instrument of communication and as a symbol of group identity, language is accompanied by attitudes and values held by its users and also by persons who do not know the language. For example, although few readers of this book know American Sign Language, most hold some value judgment about this manual-visual language, which they may have seen on TV. What is important to realize, however, is that attitudes toward a language—whether it is beautiful, efficient, rich and so on—are often confounded with attitudes toward the language from attitudes toward its users, the Deaf [Grosjean 1982, 117].

Risa’s willingness to seek change required taking small steps to have a closer relationship with her deaf brother. To her, it was worth the time invested and the continued effort necessary to learn ASL, in spite of the tedious task of memorizing vocabulary and using the grammar unlike hers. During the interview, her brother expressed his support, “She was nervous. She would gesture to make sure I understood. I told her she was good and saw that she was relieved.” Deaf siblings were in agreement that ASL was the bridge to getting closer to their siblings, and they had come to that conclusion not only based on their interactions in ASL with their peers, but the opportunity to have a closer relationship with their sibling made it even more compelling. Nevertheless, with Risa as the exception, all of the non-signing siblings, who used spoken English with their deaf siblings as children, continued to follow their parents’ communication model. With these unresolved differences, these siblings remained unsatisfied in their relationships.

Parents are the decision-makers; they decide what language will be used in the rearing of their deaf child. They model what professionals advise them to do, often tempered with their own experiences and beliefs. The agony of having a deaf child did not prevent one sibling’s mother from bringing her judgment to the advice of professionals. Randall was grateful for his mother’s defined goal: communicating with her deaf child now!

When she found out I was deaf, she asked the doctor, “What should I do?” She was lucky the doctor recommended she explore different methods such as oralism, Cued Speech, and others. My mom visited an oral school and observed there briefly. With Cued Speech programs, it was difficult because mom had to call different places and most of them were located too far since she preferred a program closer to home. Then, she went to Parkland school.1She said what impressed her mostly was when she went there … a teacher had a ball and when she signed “ball,” I copied it right away. Mom was taken aback and asked what the sign meant. She was blown away by how quickly I was able to grasp the idea. Mom wanted to also check out the Clarke School for the Deaf. She said what was most convincing, which led her decision not to use the Oral approach, was when they advised her: “You’d have to wait between two to three years where you cannot communicate with your son. Then, it will be fine afterward.” They quickly added that she couldn’t sign either; the focus was to be solely based on speech. Mom asked herself whether she could bear two years during a dinner meal not communicating at all with me.

The hearing mother wanted her deaf child to have what her son and every child has when acquiring language: a mother tongue, which provides access to one another’s conversations and reinforces the power of “learning by osmosis.”

One of the deaf siblings, Rami, gave an example of the osmosis effect pervading the interaction between a hearing mother and her seven-year-old deaf daughter:

There was a family of three—the mother was a fluent signer—an interpreter quality. The father signed too but had mediocre skills. Approximately two weeks after having found out about their kid’s hearing, the mother registered for a sign class. She was in a conversation with another hearing mother. They were talking, not signing, with one another. As soon as she turned and saw her kid approaching, she automatically switched to signing so that her daughter could watch their conversation. The other mother caught on and started signing too. The kid watched their conversation for a while—that is learning by osmosis. Then, the kid would ask the mother a question; the mother would teach the kid by signing, “When you tap me, please say excuse me” so the kid would sign, “Excuse me” and the mother would turn to the other mother and say, “Excuse me” to proceed with her conversation with her daughter. They would converse in ASL and the mother would answer her daughter’s question. If the daughter didn’t understand, she would ask her mother to fingerspell again. The mother adapted the fingerspelling by using another communication mode, cued-speech, so that way the kid would perfectly pronounce the word she missed. Then, the mother would use ASL to sign the meaning of the word. Then, they proceeded with the rest of the conversation. This girl was profoundly deaf and was capable of speaking, signing and learning simultaneously from the conversations she was observing and understanding.

Unequivocally a person needs to have effective and accessible communication at an early age in order to develop language. “Parents and siblings need to put forth all effort they can to make sure the communication environment is visually accessible, not only when addressing the deaf child. Seeing how adults talk to each other is one of the major ways that children learn how people communicate, negotiate, and share” (Marschark and Hauser 2012, 62). Furthermore, to be a functional member of American society, all children need to be literate and communicate naturally, receptively and expressively.

How is it that neurologically normal persons like the deaf people Pinker describes are made to feel so diminished based solely on hearing status, not intelligence, talents or ability to interact with people? Why was being deaf so stigmatized? What the policy makers gain by stigmatizing deaf people was not only power over deaf education but the financial gains to be had from jobs as a result of the consequences of Oralism: a century of dismal educational achievement leading to severe unemployment and underemployment of several generations of deaf people who, unlike their deaf predecessors prior to 1880, rarely achieved literacy. In 1996, three scholars, Harlan Lane, Robert Hoffmeister and Ben Bahan, reported the profound consequences: “We have seen that, after nearly a century of Oralism, the average Deaf high school graduate had achieved a third-grade education. Alas, after twenty-five years of TC, the results have not improved” (Lane and Hoffmeister and Bahan 1996, 271). Each generation strives to do better than the previous generation in the field of education through hands-on approaches with teaching, training, and research. The third-grade reading level among deaf children had become the norm using the English-based Sign systems lacking the fundamentals of a language.

Simultaneously, ASL had begun to earn respect in academic circles, prompting educators to search for a different approach. Deaf professionals, strong proponents of language acquisition in the field of deaf education, fought to use bilingual techniques with deaf children. An exemplary approach was taken by a native ASL user from a deaf family, Marie Phillips, who pioneered in the Bicultural Bilingual (Bi-Bi) approach, believing that deaf children could become bilingual, acquiring ASL and English simultaneously. She took the lead as the Bilingual-Bicultural Coordinator of the Learning Center for the Deaf in Framingham, Massachusetts, creating an academic environment where deaf children would become bilingual, equally proficient in ASL and English (The Learning Center for the Deaf n.d.). Few deaf schools sought to use her model by sending their educators to observe and get trained using her approach for research. The majority of professionals and families remained skeptical about the long-held belief that learning ASL inhibits learning speech. The evidence proved otherwise, as one educator, Dr. Mark Marschark, declared:

It is easy enough to understand the desire of most hearing parents to have a child who speaks and acts normally. The truth is, however, that most deaf children will never sound like their hearing brothers and sisters. Delaying the learning of sign language in the hope of developing better speaking skills in deaf children simply does not work in most cases. In fact, such delays can make matters more difficult for both children and their parents. The first years of life are when basic language skills develop, and the first two to three years are generally recognized as a critical period for language learning. There is no substitute for natural language learning, and language acquisition that begins at age three or four is not natural [M. Marschark 1997, 14–15].

In addition, although the elementary and middle schools on the campus of Gallaudet University provided a Bi-Bi program through the groundbreaking efforts of M.J. Bienvenu, Professor of ASL and Deaf studies, none of the siblings in this study attended Bi-Bi programs. However, the parents who sent their deaf children to the few Bi-Bi schools are indications that respect for using ASL had arrived, at least in some families.

As they told their stories, the siblings we interviewed searched for tools to alleviate the emotional scars resulting from their parents’ continued use of only speech and lipreading to communicate with their deaf family member. For some, the psychological reverberations created an impenetrable distance between deaf and hearing siblings. For others, like a magnet the search brought them together, conveyed to us in soul-searching stories, often defining their sibling relationships on a continuum—from best friends to bitter enemies. The consequent lack of access to a shared language ostracized some deaf siblings who never felt at home in their families. Regardless of constant pleas by parents and hearing siblings insisting deaf siblings be at home for family gatherings, many deaf siblings ultimately substituted deaf peers for family. The bond these deaf siblings had with their peers was too powerful to ignore: The shared deaf identity and a common language—ASL—and their cultural ties, created a world in which they felt at home. Even when families are using sign and spoken English in the home, creating the experience of bilingualism, home is often the place where biculturalism—deaf culture—is absent. Being bilingual does not guarantee biculturalism. By immersing the family in deaf community events, they learn the social rules and ways to interact in the DEAF-WORLD, similar to living in a foreign country, which is traditionally been the way to absorb that country’s culture.

Paddy Ladd, a British deaf scholar of Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood, poses the following question:

Imagine that all children with a hearing loss on a scale that inhibits meaningful interactions with mainstream societies were brought up bilingually and biculturally; that they were told throughout their childhood, “By learning both spoken and sign languages, you can learn to navigate your life path in and around two cultures and two communities, selecting whatever you wish for from either in order to build your own lives.” Is this not culturally-centered perspective a more healthy social philosophy than the medical one which stresses the shamefulness of association with signing communities? [Ladd 2003, 34].

The shamefulness of association with signing communities is a form of oppression of deaf people and their families, especially their siblings.

One hearing sibling, Anita, who worked as an educational interpreter for deaf students, shared her concerns:

There was this condescending attitude towards these deaf kids who were treated as dummies because they didn’t know a lot of things. Yet, on the other hand, they didn’t want you to use ASL, they wanted you to Sign in English. The woman who was running the department couldn’t really Sign very well and she was “running” the department! Additionally, they didn’t treat these kids as though they were part of the mainstream. They had to come to a special resource room for us to tutor them and they were seen as different. The staff knew that there were those types of people working there, but they all backed down. None of them would get into those people’s faces. They were afraid.

This was yet another instance of the lingering effects of Milan, over one hundred years later, when MCE systems were used. As a sibling of a deaf person and an ASL interpreter, she was baffled at administrators’ decision to forbid ASL, thereby rejecting deaf culture and deaf people; she had seen ASL not only open her deaf brother’s mind, but ASL was the link to his understanding of the world around him. Perhaps most critical, she was working in an educational system that diminished and inhibited deaf children’s psychological and cognitive development. When she saw how engaged she and her brother could be casually chatting in ASL about evolution, it was an epiphany. No longer were their conversations limited to three- or four-word question-and-answer sentences like what they did when he was in an oral elementary school. As soon as her brother transferred to the state residential deaf school, she witnessed his cognitive, linguistic, and cultural competency flourishing with his classmates and deaf house-parents and then, at home, with her. Consequently, she adopted a worldview about the presence of ASL as the vehicle for her and her deaf brother to interact as equals.

While the events of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century caused an upheaval in the education of deaf children and within their families, simultaneously, earthquakes occurred in the microcosm of the DEAF-WORLD: Gallaudet University, the world’s only institution of higher education for deaf and hard of hearing, deaf-blind, and late-deafened students. In 1988, the Board of Trustees appointed a hearing person as the incoming president. To protest, three deaf representatives met with the Board Chair, Dr. Jane Bassett Spilman: “It was at this meeting Spilman is purported to have said, ‘Deaf people are not ready to function in a hearing world,’ a statement she later said was misinterpreted. She had used a double negative” (Gannon 2002, 37).

Nevertheless, student protests erupted, headlined with banners of “Deaf President Now (DPN).” Protesters were supported not only by faculty members but also by Gallaudet alumni and local communities throughout the country, causing a campus shutdown, reminiscent of student protests during the 1960s Civil Rights movement. The Board finally relented, appointing I. King Jordan, a late-deafened candidate, to the position. Choosing a late-deafened person, rather than several congenitally deaf candidates, was a compromise giving a message to the world: a person with a hearing loss was now acceptable and capable of leading. The tensions between students and faculty with the board caused more than a ripple effect throughout the country, raising awareness that being deaf was a prerequisite for the incoming president of Gallaudet University. Siblings we interviewed were aware of the DPN events at Gallaudet, though the younger ones learned about it as history at DEAF-WORLD lectures about the far-reaching effects of audism. The siblings’ stories unmasked how audism permeated their homes and school environment and have continued to create further emotional and social distancing from their families and peers.

Additionally, even within the core of the DEAF-WORLD, different forms of audism existed. The most prominent example was the 2006 protest surrounding the appointment of Dr. Jane Fernandes as the next president of Gallaudet University. However, shades of audism were present long before, when she was the provost responsible for the development of the Strategic Plan for Gallaudet’s future. As a deaf woman in a powerful leadership position at the world’s only deaf university, she never took advantage of the opportunity to take a stand to define the university’s language policy as one that gave equal value and equal respect to ASL and English. Instead she created a division, forcing students and faculty to support her values for inclusion, surrounding deaf people’s lives with all forms of MCE communication systems at the expense of ASL, and perpetuating Gallaudet’s long-term policy that neither faculty nor students needed to attain fluency in ASL, a blatant form of audism (Bauman, “Postscript: Gallaudet Protests of 2006 and the Myths of In/Exclusion” 2008).

Internal and long-held beliefs about ASL by the families we interviewed are nearly impossible to ignore. Why should deaf siblings continue to enable the oppressive behaviors and attitudes by both deaf and hearing people? Like other minority cultures, most deaf people weren’t given a chance to develop their own identities without any filters, similar to Native Americans who were taken from reservations and placed in white families. Unaware of the effects audism may have on them, deaf people are likely to oppress one another. The acceptance of audist behaviors may be explained by a theory called dysconscious audism, as proposed by Genie Gertz:

[A] sizable group of Deaf people who would be categorized as “dysconscious audists” because they haven’t developed their own Deaf consciousness and identity to the fullest. Generally their Deaf consciousness is distorted to varying degrees. Dysconscious audistic Deaf people unwittingly help to continue the kind of victimized thinking that they are responsible for their failure. Such thinking enables hearing people to continue pathologizing Deaf people [Gertz 2008, 222–223].

Audist behavior may be subtle, especially if deaf people perceive themselves as not whole. Deaf people’s varied responses to oppression are inconsistent. Dr. Gertz expands the subtlety of oppression by stating the differences in the awareness a person has toward audist behavior:

The marked difference between “unconscious” and “dysconscious” when used with the word audism is that the word unconscious implies that the person is completely unaware whereas the word dysconscious implies that the person does have an inkling of his or her consciousness but does not yet realize it is impaired. Some Deaf individuals choose to do nothing about it or to take a “so be it” attitude. In this manner, it is not that they are completely unaware of the issues; it’s just their decision on how to live with them [Gertz 2008, 223].

Why is it so painful that many barely think about it, just adapt and get on with their lives, doing what it takes to survive daily doses of oppression? Rose Pizzo, in her memoir Growing Up Deaf: Issues of Communication in a Hearing World, described her awakening:

I remember feeling I didn’t know what was going on but I didn’t think anything was wrong. I thought I was normal not to understand. That was just part of my life. I just didn’t understand and I thought it was O.K. I didn’t realize it was not O.K. until I married Vincent. I was so excited. Vincent and I could sign with each other, in our own home. My whole life, while I was growing up, I had to be with hearing people. Finally, in my house, my home, I could communicate easily with my husband, morning, noon and night, twenty-four hours a day. Wow [Pizzo 2001, 124]!

We have noted how the series of events shaped the varied identities and communication modalities of the siblings we met. In the meantime, their hearing siblings, like Marla’s brother Joseph, experience the emotional backlashes since siblings typically are mutually dependent on one another.

I saw a big change at some point in her life—when I perceived her as being angry at the world for trying to assimilate her into the hearing world. The notion of a deaf world and hearing world being completely different and at odds with each other seemed sad to me. We are rather distant so I don’t know, yet I suspect some of this thinking still exists today.

The anger is never understood because siblings have yet to find common ground and often don’t know why they are at odds. The assumption is if one sibling changes, then it means the change is an attack on the other siblings when the change is really about finding one’s place in the family and even the world.

Some deaf and hearing siblings grew up believing that being deaf and using sign was something to be ashamed of; others grew up with a strong sense of pride in themselves or their deaf siblings as deaf people, respecting ASL and deaf culture. Several hearing siblings struggled to comprehend the pride, unable to identify or feel connected to their deaf siblings’ DEAF-WORLD. In families, where siblings are taught “doing kindness unto others” as a way of expressing our moral values, there is a feeling of justice to “do the right thing,” especially when the caring becomes part of our very being.

Yet situations arise where a sibling’s sense of righteousness puts him in such unfamiliar territory—the DEAF-WORLD—that their discomfort takes precedence, even when they respect the culture and feel entitled to be part of it. This was the case when Judy and her siblings were attending an event hosted by their deaf nephew where the majority of guests were deaf adults. To get Larry’s attention while he was having a “voice-off” ASL conversation with a friend, even with several attempts to tap on his shoulder and his acknowledgment of her wanting to interrupt, Mary Ann, not knowing ASL, walked away frustrated and impatient, confiding to Judy, “I’ll never go to a Deaf event again! It is rude for them to sign and not acknowledge my presence!” This was the very same sibling who, during their childhood, had shown empathy: she defended her deaf brother, kept him in the loop, made the effort to include other deaf people she had run into at bridge games and other social events where hearing individuals predominated. What was familiar to Mary Ann was her comfort in advocating for her brother in a hearing environment. However, when it came to the DEAF-WORLD, the reciprocity was naturally expected, yet it wasn’t there. As her feelings were kept buried from her brother, behaviors like this contributed to their deteriorating relationship, especially the enormous problem of having to address the language and cultural differences emerging within the family.

Unlike their hearing siblings, like Mary Ann, who continued to use Oral communication with their deaf siblings, by 2005–2006 when we conducted many of the interviews, some older deaf siblings had personally gone through a transformation. Maxel proudly shared: “In 1988, the DPN protest happened. My world changed. People said to me before you were the quiet type, now you’re protesting.” Maxel was an active participant in the DPN movement. His transformation, as well as that of other deaf individuals, came not only from the four student leaders of the DPN movement, but also from a group of Gallaudet alumni and deaf professionals known as the “Seven Ducks.” They were primarily responsible for the “behind the DPN Movement,” along with several key deaf women leaders who maintained an essential relationship with the media, keeping them informed of events as they happened. Many of these leaders, along with numerous others from disability groups, formed coalitions as a result of DPN’s getting the press and Congress’s attention, that soon after led Congress to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (Office of Communications, Gallaudet University Spring 2013).

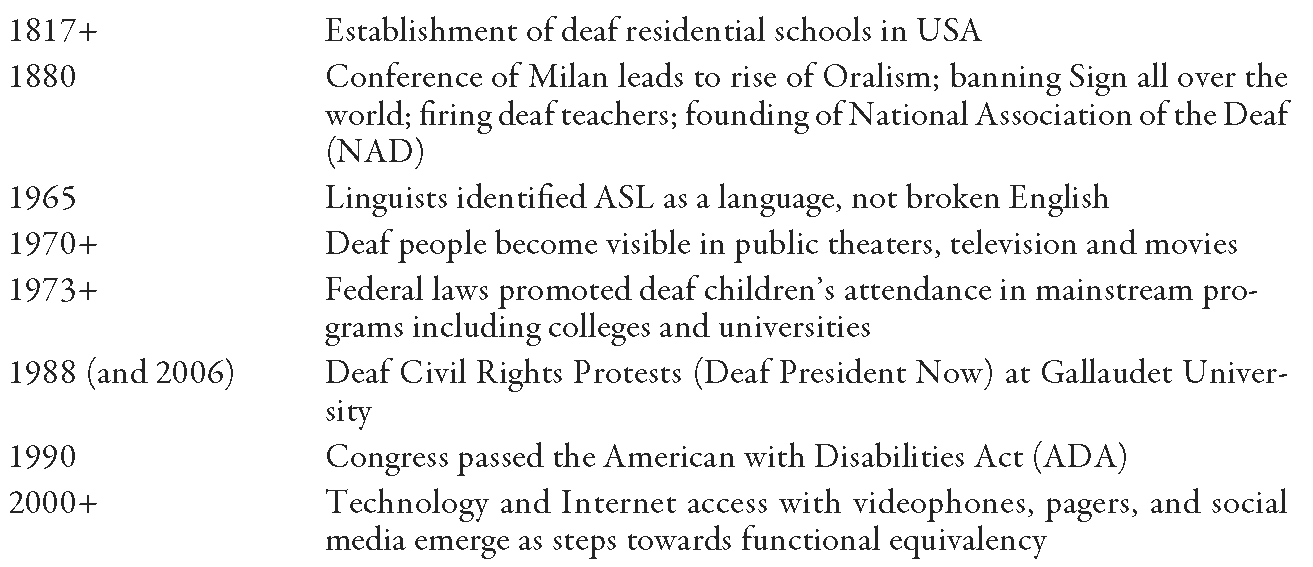

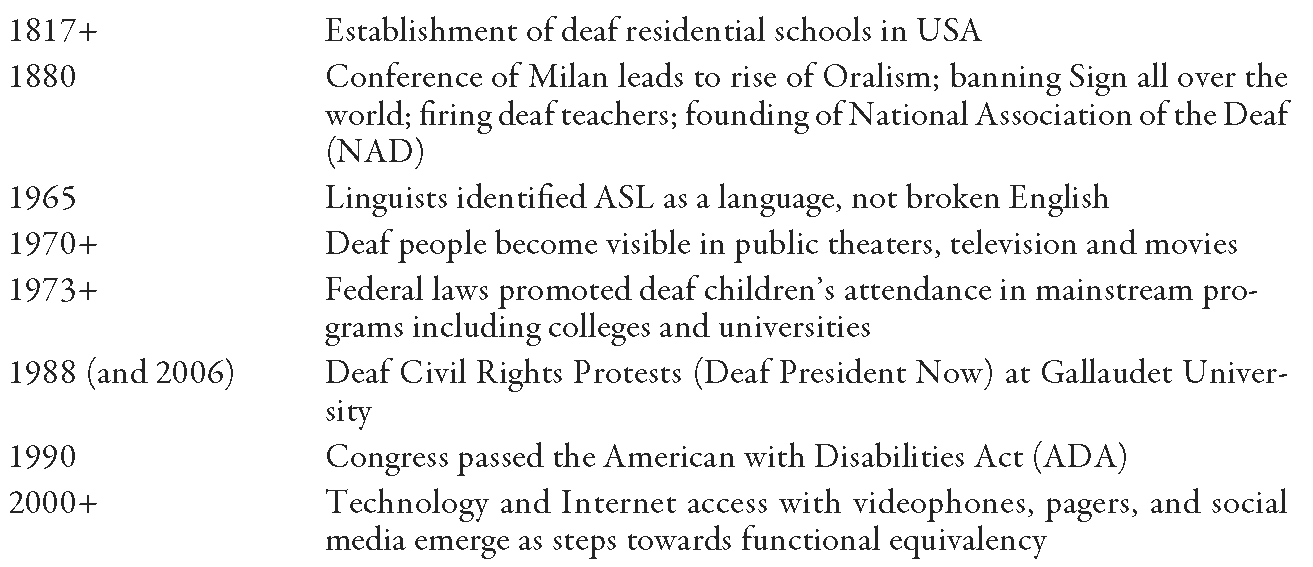

The following historical events in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have transformed the lives of deaf siblings. Consequently, as the century came to an end, their hearing siblings became more aware of the possibilities for more efficient and effective interaction.

In spite of these events, evidence of progress toward acceptance of deaf people as part of society is far from over and has yet to permeate every family, leaving siblings with much work ahead of them.

When hearing siblings are with their deaf sibling, oppression often hovers in the background. Sometimes it is in the foreground as well, when engaging with hearing relatives—the vast majority of whom do not know ASL—and during the times hearing siblings would overhear comments about their deaf sibling. Golda described her misgivings about being an ally to her deaf sibling:

Being an ally to my sister … I’ve never said anything and I don’t know why. I guess, maybe it’s that whole hierarchy. They’re my elders and I don’t want to say anything. Or maybe I don’t think it’s worth it. Or maybe it’s because my sister’s never asked me to, but why should she ask me to? You know, it’s like black people are always talking about racism. You need to have white people talking about racism. You need to have hearing people talking to hearing people about audism and oppression. You can’t have the deaf person always saying, “You oppressed me.” You know, you need to have the hearing person…. So I know … that I guess, I would be that person.

In order to conquer the premises of audism as a form of oppression, it takes those who are members of the majority culture to confront the issue. Systematic oppression contributes to the complexity of the external influences occurring in society also shaping siblings’ identity and position in the family unit.

A black feminist, Patricia Hill Collins, introduced the idea of how various forms of oppression overlap: specifically, intersectionality is “an analysis claiming that systems of race, social class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, nation, and age form mutually constructing features of social organization” (Collins 2000, 299). Any of these elements may become targets for oppression which are fluid depending on the circumstances. More evidently these forms occur simultaneously where one form of oppression shapes individual’s interactions. It begins with the person’s internal perception affecting daily relationships. If your brother was raised to think boys are superior to girls, his attitude and behavior towards his female relatives, including his siblings, reinforces the acceptance of these beliefs that eventually become the norm.

Sexual identity and gender roles have also shaped the development of how siblings relate to one another during the socialization process. Sexual identity generally refers to biological differences between males and females; however, there are times at birth when sexual identity is not clearly defined. In addition, in cases where a person “comes out of the closet” or has a sex change, the impact on the sibling relationship is likely to be profound. For example, as siblings mature, they can become more intimate even when unexpected sexuality is revealed:

Avna: He was furious that I caused the family uproar when I came out to the family.

Marla: What prompted the change in your relationship with your youngest brother?

Avna: Well, as kids, we hardly had anything to say to one another. But after the dust settled, we started to chat. We sat down and had great conversations about religion, sexual preference, just about anything. He is more accepting of who I am. I was blunt with him: “I am just telling you I’m a lesbian.”

As opposed to the biological perspective, social scientists define gender as culturally imposed masculine, feminine or intersex roles and behaviors. For example, children often challenge their culture’s expectations with respect to their talents, intellect, and interests. More specifically, children tend to formulate their own perceptions labeling what the gender role ought to be. The symbolic items culturally associated with gender vary in different parts of the world. When family members break gender roles expected within their specific culture, they and their family may be scorned by the community, or worse, by their own relatives. Experts disagree regarding the percentage that biology and the environment each contribute to gender stereotypical behavior. Apparently, evidence supports both; this is the traditional nature-versus-nurture dispute, about the impact of gender roles, decades old (Berger 2008). Marla pinpoints how her earliest memory with gender differences was affected by her youngest brother’s birth: “Joseph, as the only boy, became the joy of the family, especially for my father. It started with the Bris celebration and it ended with Joseph’s Bar Mitzvah. Like many cultures including ours, my father had a higher regard for boys and men than for girls and women. And I felt I was being penalized for being female.”

Jasmine reported how her hearing sibling defended her to confront their parents’ stereotypes. It is also an example of double oppression from the perspective of a deaf female sibling:

Marla: Can you explain how your parents were overprotective?

Jasmine: I remember vividly when my sister told me how our parents refused let her play track and field and when it came to me, she fought them to let me play soccer.

Marla: Which sister fought for you?

Jasmine: The one who always kept me abreast of family gossip.

Marla: Why do you think your parents didn’t want you to participate in sports?

Jasmine: Of course, I’m deaf and we’re girls.

The tentacles of any form of oppression are far-reaching, getting into the person’s very soul, regardless of the specific form they take. When deaf people and their hearing families believe deaf people are impaired, implying they need to be fixed, a framing trap is occurring. The trap is set from audist’s successful marketing of pathological phrases such as fix, handicapped and disabled, all of which enable victimization mentality. The deaf person then falls into a lifetime spiral of beliefs that they need to be rehabilitated, destroying their independence and self-confidence. Being deaf is as vital to their identity as their gender, sexual orientation or ethnicity, among other identities. The medical model perspective does not recognize or understand this key component of the deaf identity. Kevin described his transformation:

It’s hard for me to get this out and to confess … on the night before Christmas Eve, I did pray to God: “Please make me hearing tomorrow.” When I was in high school and during my years at Gallaudet, I looked back thinking how ridiculous that had been and was disgusted with myself for feeling this way. But when I thought about it I realized how normal it had been because my world had changed from when I was mainstreamed, being with the “hearing,” having no friends and struggling academically. Somehow I thought it was the ideal normal environment for me. It was how I processed information in my hearing school while not knowing about Gallaudet or a Deaf school. It wasn’t until I entered a Deaf school, I found myself totally relieved and in awe with ASL—full access to communication and social interactions. Then, I felt I was normal once again.