Bucentaure (1803)

Bucentaure (1803) Bucentaure (1803)

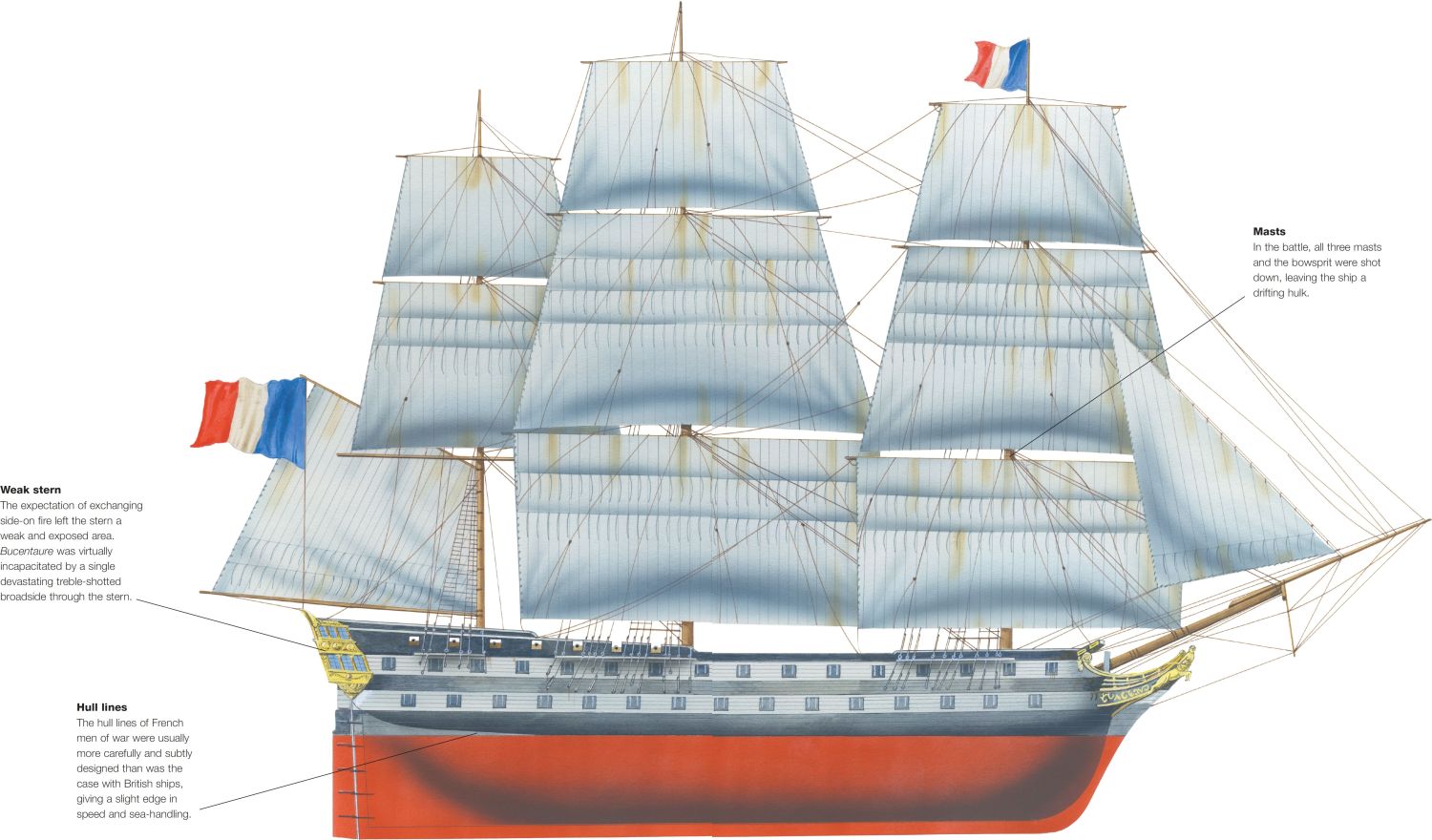

Bucentaure (1803)A new, handsome, well-proportioned 80-gun ship of the line, it was the flagship of Admiral Villeneuve, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Bucentaure was the first of a class of 80-gun ships for the Imperial French Navy. Sixteen were launched between 1803 and 1815, with a further five up to 1824. The designer was Jacques-Noel Sané. Sané was an advocate of uniformity in ship design, and beginning with Tonnant in 1789, was responsible for a series of excellent ships. Armed with 84 guns, they were classified as second-rates, but outgunned the typical British 74-gun ship and were easier to handle than the massive 100-gun first-rates.

Bucentaure’s name commemorated the French capture of Venice in May 1797: it was taken from the name of the Doge’s state barge, Bucintoro.

This painting by Auguste Mayer (1805–90) was long thought to show the dismasted Redoutable but has been shown in fact to represent Bucentaure. The British ship’s stern bears the name ‘Sandwich’ but HMS Sandwich was not at Trafalgar.

Longer than their British counterparts, more solidly constructed and heavier, they were well-rigged and can fairly be claimed to be the best ships of the time. Some commentators consider there to be a single class from Tonnant to the final example, Vesuvio, not launched until 1824 and sold to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

The great problem for the French captains was not the quality of their ships but that of their crews. The British Navy had worked harder to train its officers and crews, helped in this respect by having far more ships at sea, and for longer periods. The British crews were healthier, with the shipboard scourge of scurvy largely prevented. The French captains considered their crews to be a rabble. There is a phrase attributed to Nelson: ‘The best navy in the world would be made of French ships and English crews.’ But English crews also contained their full share of pressed men, freed prisoners and army deserters.

Laid down at Toulon in November 1802, Bucentaure was launched on 13 July 1803 and commissioned in January 1804. From first service it was a flagship, at first of Vice Admiral Latouche-Tréville, who died on board, to be succeeded by Vice Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve from 6 November 1804. In September 1805, the Combined Fleet was at Cadiz, when an order from Napoleon instructed Villeneuve to embark troops and set sail for an invasion of Naples. Cadiz was already closely watched by the British, and there was little chance of leaving it without a battle. But Villeneuve learned that he was to be replaced by Admiral Rosily, and despite having decided in September that the Combined Fleet was not capable of action, he resolved to take his ships to sea and vindicate his post in the eyes of Emperor Napoleon.

They left Cadiz on 21 October. On paper, Villeneuve had a superior force, with 33 ships of the line (18 of them French) and seven frigates, and with 2856 cannon at his disposal, while Nelson had 2314, on 27 ships of the line and six frigates. But the British admiral had seven three-deckers while Villeneuve had only four.

Bucentaure was commanded by Captain Jean-Jacques Magendie, and in the line it took a central place. As the British, in their two divisions, advanced, Villeneuve’s last signal was similar to Nelson’s: ‘Every ship which is not in action is not at its post, and must take station to bring itself as speedily as possible under fire.’ Victory fired a broadside that ripped into the transom of Bucentaure at a range of only 9m (30ft), sweeping the decks with shattering effect. In a few minutes Victory, Bucentaure, L’Indomptable and HMS Temeraire were all abreast of or inboard each other, rolling together, spars crashing, gunshots blasting off. At 13:40, shots from HMS Conqueror brought down the main and mizzen masts.

At 13:45, now drifting helplessly in the midst of the battle, with the bowsprit and all three masts fallen, and half the crew killed or wounded, Bucentaure was described as ‘a mass of wreckage’ by the Captain. Villeneuve tried to have his barge launched, to transfer his flag to a ship still able to fight, but the boat was crushed beneath fallen spars. With no alternative but to surrender Bucentaure struck its colours to Conqueror. Villeneuve and Magendie were taken prisoner. A British prize crew was put on board, with the surviving French crew held on board as prisoners, and the ship was attached by a towline to Conqueror, but the line parted. The Frenchmen managed to break out and retake the ship, but in the storm which arose on the 23rd, it was unmanageable. The ship struck a reef off Cadiz Bay, and foundered, with a handful of survivors.

Specification

Dimensions |

Length 59.3m (194ft 6in), Beam 15.3m (50ft 3in), Draught 7.8m (25ft 6in), Displacement 1455 tonnes (1604 tons) |

Rig |

3 masts, full ship rig |

Armament |

30 36-pounders, 32 24-pounders, 18 12-pounder cannon; 6 36-pounder howitzers |

Complement |

866 sailors and marines |

The crew

The crew was divided into gentlemen-officers, petty-officers (illustrated right), men, and supernumeraries. The first category numbered 14, including a Commander (capitaine de frégate) as No. 2 to the Captain (capitaine du vaisseau); purser and a chief medical officer, plus nine midshipmen. The second category included two boatswains, and 25 boatswains’ mates; two master-helmsmen or quartermasters and 13 mates; 55 master gunners and their mates; two master blacksmiths and 13 mates; a master-carpenter and seven mates; a master caulker and seven mates; a master-sailmaker and two mates; and a master-at-arms. There were four rated grades of seaman, each with 95 men, 125 unrated new recruits, 60 powder-boys and 129 marines. Supernumeraries were three armourers, five surgeons, nine cooks and 11 servants.