Royal Sovereign (1892)

Royal Sovereign (1892) Royal Sovereign (1892)

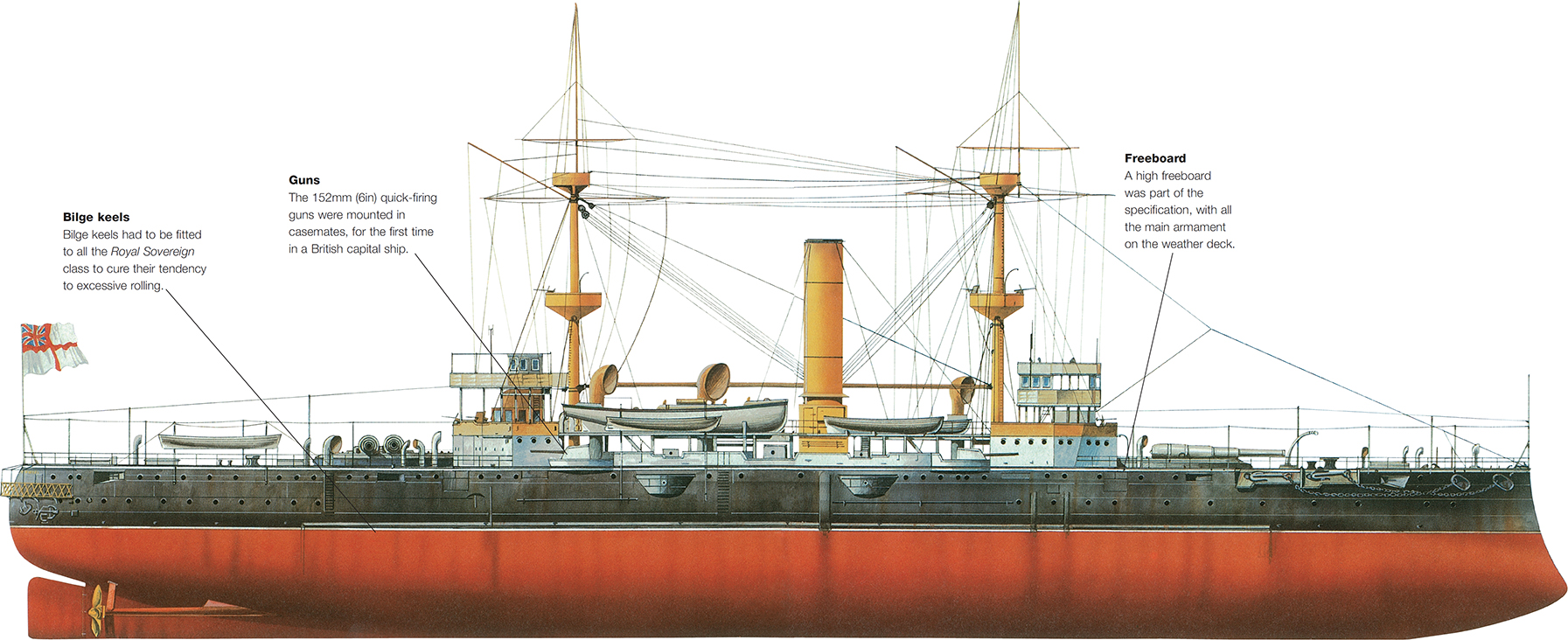

Royal Sovereign (1892)This was the first British battleship to exceed 10,886 tonnes (12,000 tons) displacement, and the first to have steel-plate armour. In the words of one expert commentator, it was the first of a class of seven which ‘sat the water with majesty and distinction’.

It took three-plus years from the laying-down to the completion of a first-class battleship. At the end of the 1880s British naval design was emerging from a period of often confused experiment and design which tried to catch up with what other nations were doing, into a more confident phase, in which a whole class of capital ships could be planned for. Shortly before that, there was a long moment when it seemed that the age of the battleship had already come to an end.

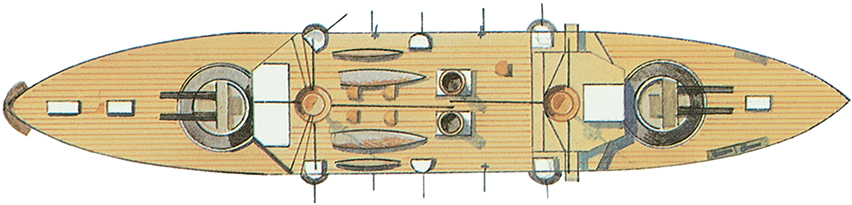

This was the first class of British battleships to carry all their main armament on the weather deck, an innovation made possible by the 5.5m (18ft) freeboard and the use of barbettes rather than turrets.

As the cost of a capital ship edged towards £1,000,000, politicians and planners were preoccupied by the fear that a single torpedo could potentially destroy it. France actually put a temporary stop to battleship construction in the late 1880s. But as it turned out, in the words of the First Lord of the Admiralty in March 1889: ‘the power of these torpedo boats had been greatly exaggerated by naval officers’. Capital ships still had a role. The Naval Defence Act of 1889 provided for the construction of no less than 70 ships, including eight large battleships of 12,836 tonnes (14,150 tons) and one of 9525 tonnes (10,500 tons). At the time, Britain possessed 22 first-class battleships and 15 second-class; France had 14 and 7 respectively, and Russia had 7 and 1. Germany, watching developments with interest, was about to expand its battleship strength.

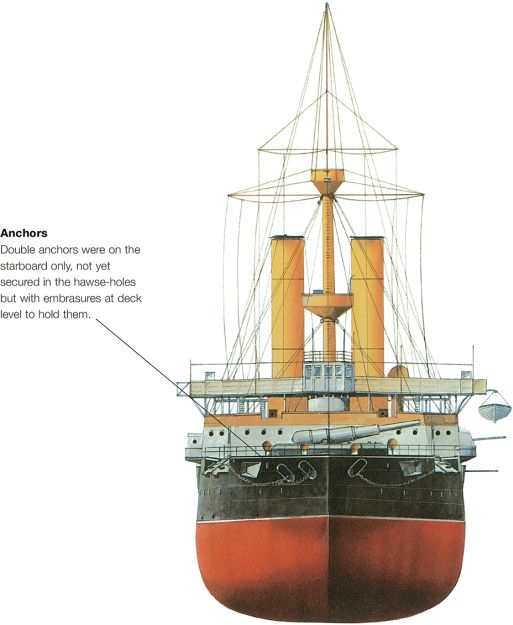

The seven large battleships were to form the Royal Sovereign class, and the name ship was laid down at Portsmouth on 30 September 1889, launched on 26 February 1891, and completed in March 1892, at a cost of £913,986. It was a barbette rather than a turret ship and the consequent reduction in weight enabled it to ride higher in the water and to achieve a greater speed. This was quite a radical departure in design, compared with previous years, but familiar to those who recalled the sailing men of war; like those, Royal Sovereign had an inward slope of ‘tumblehome’ on the sides to help keep the vertical centre of gravity safely low (the Director of Naval Construction, Sir William White, is said to have copied contemporary French warships in this respect, though he did not incorporate sponsons, in the Royal Sovereign class anyway).

Specification

Dimensions |

Length 115.8m (380ft), Beam 22.86m (75ft), Draught 8.5m (28ft) (full load), Displacement 14,138 tonnes (15,585 tons) (full load) |

Propulsion |

8 cylindrical single-ended boilers, 2 sets of 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engines, 6711kW (9000hp), twin screws |

Armament |

4 343mm (13.5in) guns, 10 152mm (6in) QF, 16 6-pounder QF and 12 3-pounder QF guns; 7 356mm (14in) torpedo tubes, 2 submerged |

Armour |

Belt 457–356mm (18–14in), Bulkheads 406– 356mm (16–14in), Deck 76–63mm (3–2.5in), Barbettes 432–279mm (17–11in), Casemates 152mm (6in), Conning tower (forward) 356mm (14in), aft 76mm (3in) |

Range |

8741km (4720nm) at 10 knots |

Speed |

18 knots (maximum under forced draught) |

Complement |

712 |

Armour

From the late 1870s, steel armour had been tried out, and in Britain a compound, with a steel face welded on to iron plates, had been in use from the mid-1880s. The French firm of Schneider had developed an effective steel armour by 1881, and both the Americans and the Russians used this. The British, unable to match the Schneider product, continued with the steel-faced compound. In 1889 a nickel-steel alloy was developed, and in 1891 the American metallurgist H.A. Harvey produced a new kind of ‘Harvey steel’, face-hardened by the application of carbon at very high temperature and subsequent tempering and annealing. Royal Sovereign’s belt and barbette armour was of the old compound type, but the hull parts beyond the belt were of 127mm (5in) ‘Harveyised’ steel, backed by coal bunkers. This was considered to offer enough resistance to medium-calibre shells.

One member of the class, HMS Hood, was built as a turret ship and was conspicuously less successful than the other six, both as a seaboat and as a fighting ship, its guns sitting 1.83m (6ft) lower and its decks regularly awash. Like some preceding capital ships, including HMS Trafalgar, Royal Sovereign had two funnels side by side, placed above the division between the two boiler rooms which were set in line, with the engine room aft. As was by now standard, twin screws were fitted.

Royal Sovereign’s barbettes, housing four 343mm (13.5in) BL guns, were of similar shape and design to those of Collingwood, of 152mm (6in) armoured steel, though the armoured walls extended down to belt level. The secondary armament of 10 152mm (6in) guns were placed in armoured casemates 152mm (6in) thick on the main deck level, and behind gun-shields on the upper deck (altered to casemates on refit in 1903). Six-pounder guns were distributed along both decks and 3-pounders were placed on the shelter deck and in fighting tops of both masts. Seven 356mm (14in) torpedo tubes were incorporated, but this was altered to four 456mm (18in) in a 1903–04 refit at Portsmouth. Royal Sovereign was initially assigned to the Channel Fleet and was part of the British squadron at the ceremonial opening of the Kiel Canal in June 1895. From June 1897 to August 1902 it served in the Mediterranean (one of the 152mm (6in) guns exploded in November 1901, killing six men) and was then guardship at Portsmouth until 1905.

The barbettes were pear-shaped in plan, extending under the deck structures. Though with a maximum 432mm (17in) armour depth, their exposure of the guns was a weakness.

On reserve at Devonport from May 1905 to February 1907, it was subsequently put on ‘Special Service’ with a skeleton crew. From April 1909 to 1913 it was a part of the 4th Division of the Home Fleet. In October 1913 it was sold off.

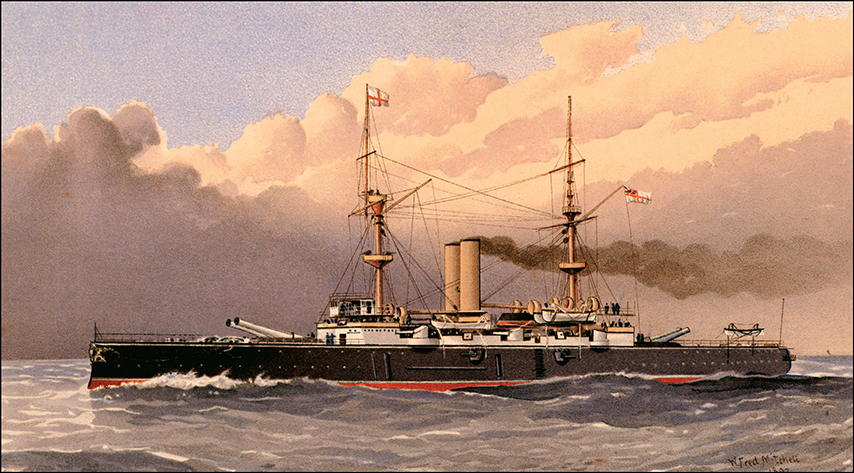

The marine artist William Frederick Mitchell (1845-1914) was commissioned to paint a range of British warships. This chromolithograph shows Royal Sovereign cruising, with guns slightly raised.