Texas (1914)

Texas (1914) Texas (1914)

Texas (1914)USS Texas saw service in both World Wars in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and the Pacific. The first US warship to launch an airplane, it still survives as a museum ship at La Porte in its name state.

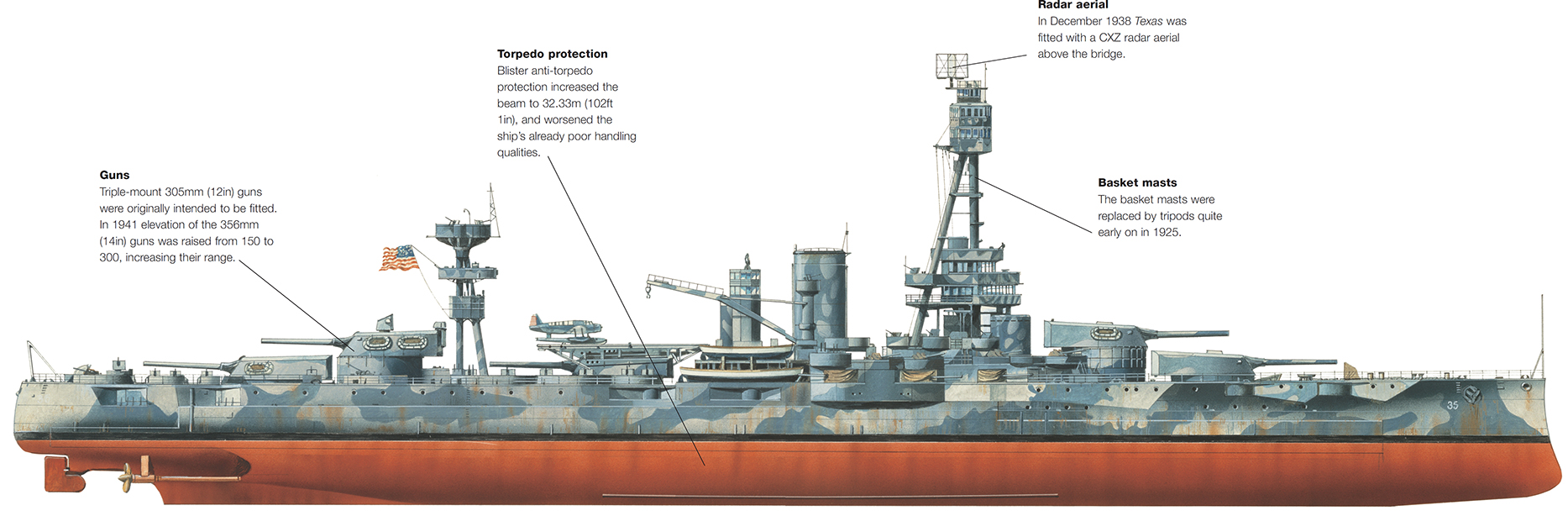

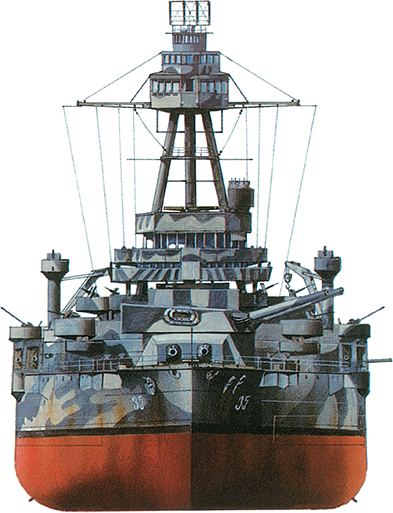

Texas had pennant number BB35 and its sole class sister, New York, was BB34, though Texas was first to be laid down at Newport News on 17 April 1911. It was launched on 18 May 1912 and completed a month before New York in March 1914. Slightly larger than the preceding Wyoming, it carried heavier guns and cost $4,962,000 against Wyoming’s $3,856,000 (excluding guns in both cases). The first US battleship to carry 356mm (14in) guns, Texas had five twin turrets, three aft of the after-mast. Placing of the central turret shortened the superstructure as in other US battleships of the time, and the basket masts and twin funnels made a compact grouping.

As commissioned in 1914, Texas had two basket masts, set closely fore and aft of two equal-size funnels, giving it a quite different profile to the post-1935 form shown here.

American battleships were quite tubby compared to British ones; in both Wyoming and Texas the ratio of length to beam was 6/1, while in HMS Lion it was 7.9/1. But Texas needed ample beam to fire its massive 10-gun salvo.

Barrel length was 13.7m (45ft), with a weight of 57 tonnes (63 tons), and firing shells of 635kg (1400lb). Each turret weighed 784 tonnes (864 tons). The guns elevated to 30 degrees and maximum range was 30,000m (32,800yd). Triple-expansion rather than turbine engines were installed due to disagreement between the naval authorities and the engine builders over the turbine specification. They were fired by 14 Babcock coal/oil boilers.

In 1914 there was a military-diplomatic crisis between the USA and Mexico, and Texas was first deployed in support of a US troop landing at Vera Cruz, and was then stationed off Tampico. From 1915 it was part of the Atlantic Fleet. As a unit of Battleship Division 9, it was due to cross the Atlantic to join with the British Grand Fleet, but ran aground at Block Island on 16 September 1917 and had to undergo repair at New York Navy Yard. It finally reached Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands on 11 February 1918, from where it participated in convoy escort and North Sea patrols.

Specification

Dimensions |

Length 174.5m (572ft 7in), Beam 29m (95ft 3in), Draught 8.7m (28ft 5in), Displacement 24,494 tonnes (27,000 tons) |

Propulsion |

14 boilers, 2 vertical triple-expansion engines developing 20,954kW (28,100hp), 2 screws |

Armament |

10 356mm (14in) guns, 21 127mm (5in) guns, 4 533mm (21in) torpedo tubes |

Armour |

Belt 304–254mm (12–10in), Deck 76mm (3in), Turrets 356mm (14in), Barbettes 305mm (12in), Conning tower 305mm (12in) |

Range |

14,816km (8000nm) at 10 knots |

Speed |

21 knots |

Complement |

1530 |

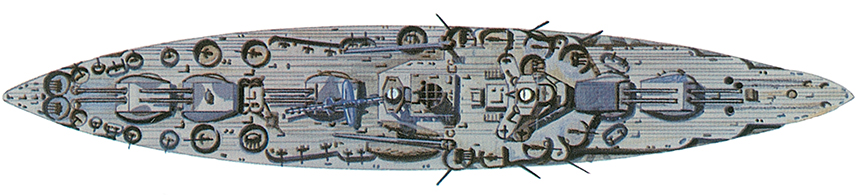

On return to the USA, Texas became the first US battleship to launch an aircraft on 19 March 1919. From that year until 1924 it was with the Pacific Fleet, then returned to Norfolk for a major modernisation between 1925 and 1927. Tripods replaced the basket masts, with the after one now set between ‘C’ and ‘D’ turrets. Six Bureau-Express oil-fired boilers replaced the previous arrangement, and the two funnels were replaced by a single one. A catapult was fitted on the central ‘C’ turret and cranes replaced the former derricks on each side of the funnel.

A photograph of USS Texas, circa 1914, just back from foreign waters, its main guns and basket mast prominent.

Within the hull the torpedo tubes were removed (only one battleship is known to have fired a torpedo in combat in World War I), a new torpedo bulkhead was provided, along with a triple bottom in the midships section, and the horizontal armour was strengthened. As a result of the modifications the ship’s displacement was increased by some 2721 tonnes (3000 tons) which had an adverse effect on handling, especially in rough conditions. In the 1930s it served first with the Atlantic then the Pacific fleet, and as a training ship. Further modifications at that time included the removal of the topmasts in 1934–35, and the addition of AA guns mounted on the tripod platforms. In 1938, a compact CXZ radar aerial was fitted above the bridge.

During 1940–41 Texas made patrols in the western Atlantic for the protection of US shipping against the belligerents, then, following American entry into the war, it operated as a convoy escort – a duty in which its comparatively low speed was not a problem. In November 1942 it provided artillery support for Allied landings in Morocco and Algeria, repeating the role in the Normandy landings of 1944 and also in southern France in the same year.

In 1942 an SG radar aerial was fitted to a platform on the foremast, and SK radar was added on the aftermast in 1943. Also from 1943 six 20mm (0.79in) AA guns were mounted on the top of ‘B’ turret.

From late 1944 Texas was redeployed in the Pacific and saw action at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Between 1941 and 1945 the ship fought in a total of 116 actions. It was the first of several battleships to be transferred by Act of Congress from the Navy to become a museum ship in 1948.

The deck plan shows the post-conversion layout, with single funnel, and tripod mainmast set aft of the centre turret.

Take-off platform

The ‘take-off platform’ was originally fitted to Texas’s ‘B’ turret during the 1919 refit at the New York Navy Yard. It was used to launch a British Sopwith Camel aircraft. Use of aircraft on capital ships began in 1914–18 and was initiated by the British. The key item was a floatplane that could be launched by catapult, land on water and be craned back on to the parent vessel.

Aircraft were used for reconnaissance and were more versatile than tethered balloons, which were also used. By the 1920s, the US Navy was using American-built aircraft, beginning with the Vought Corsair in 1927, then the Keystone OL9 in 1930, the Curtiss SOC 4 Seagull (1934), the Vought OS2 U-1 Kingfisher in 1941, the Curtiss SO3 C-2 Seamew in 1942 and the Curtiss SC-1 Seahawk in 1944. By late World War II, carrier-borne planes were available in such numbers that the British and Americans largely dispensed with auxiliary aircraft on battleships, though the Germans and Japanese used them to the end.