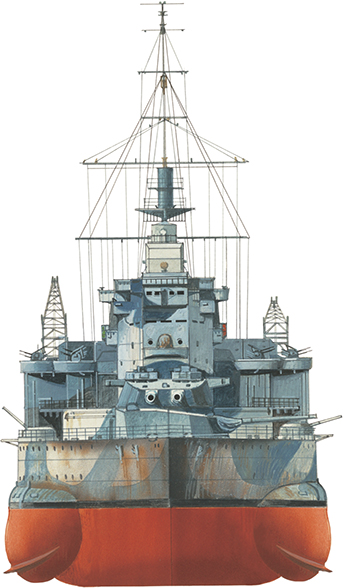

Queen Elizabeth (1915)

Queen Elizabeth (1915) Queen Elizabeth (1915)

Queen Elizabeth (1915)A ‘super-dreadnought’, class-leader of five battleships that served in both world wars. In World War I their speed and firepower set them apart from the rest of the Grand Fleet as a separate battle squadron.

Laid down at Portsmouth Dockyard on 27 October 1912, launched less than a year later (16 October 1913) and commissioned on 19 January 1915, Queen Elizabeth’s design was influenced by reports and rumours about the battleship designs of other powers, suggesting that the USA and Germany were planning higher-calibre naval guns. Consequently, 381mm (15in) guns were ordered, and though only eight were to be mounted it was felt that their weight of impact would more than make up for their number. At this time the Germany Navy’s biggest guns were 304mm (12in) and most were 279mm (11in).

Queen Elizabeth in 1943, with augmented AA armament and radar equipment after a refit in the United States. The aircraft and catapult were soon removed.

Six ships in the class had been planned but the sixth was not built (its name, Agincourt, was applied to a dreadnought carrying 14 304mm (12in) guns originally ordered by Brazil, sold while building to Turkey and confiscated by the British government in August 1914). Queen Elizabeth’s guns had barrels 12.8m (42ft) long, weighing 86.6 tonnes (95.5 tons) and firing shells of 875kg (1929lb), the heaviest naval shells used in World War I. The range was 32,000m (34,995yd) at an elevation of 30 degrees (the original maximum elevation was 20 degrees). Each turret weighed 928 tonnes (1023 tons) and was crewed by 75 men. Secondary armament consisted of 16 quick-firing 152mm (6in) guns mounted laterally in casemates. These were reduced to 12 by 1916, and two 102mm (4in) AA guns were installed.

At this time, Zeppelin airships rather than airplanes were the main threat, though they also presented a more substantial target. Four beam-mounted underwater torpedo tubes were also installed. Power was supplied by 24 Babcock & Wilcox boilers in eight boiler rooms, serving Parsons turbines, high-pressure forward drive, low-pressure reverse drive and driving four propellers, plus a ‘cruising’ turbine that drove the outer screws at cruising speed. For the first time in any battleship only oil fuel was used, with a bunker capacity of 3084 tonnes (3400 tons).

Queen Elizabeth around 1918. By this time torpedo booms and nets were no longer carried as a necessary part of a battleship’s defensive equipment. Facing page: Queen Elizabeth around 1940.

Specification

Dimensions |

Length 195.34m (640ft 11in), Beam 27.6m (90ft 6in), Draught 9.1m (30ft), Displacement 24,947 tonnes (27,500 tons); 29,995 tonnes (33,020 tons) full load |

Propulsion |

24 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 4 Parsons geared turbines, developing 55,927kW (75,000hp), 4 screws |

Armament |

8 381mm (15in) guns, 16 152mm (6in) guns, 2 76mm (3in) AA guns, 4 533mm (21in) torpedo tubes |

Armour |

Belt 330–102mm (13–4in), Bulkheads 152– 102mm (6–4in), Barbettes 254–102mm (10–4in), Turrets 330–127mm (13–5in), Deck upper 45–32mm (1.7–1.2in), Deck lower 25mm (1in) with 76mm (3in) over steering gear |

Range |

13,840km (7500nm) at 12.5 knots |

Speed |

23 knots |

Complement |

951 |

Standard practice in most navies was for a battleship’s armour to be of thickness equivalent to its gun calibre, but from Dreadnought (1905) onwards British designers had not followed this precept, in effect reducing armour in the interest of greater speed. On the Queen Elizabeth class, the maximum thickness was 330mm (13in) and this was applied only in a midships belt 1.2m (4ft) wide. Beyond this section, the armour tapered to 102mm (4in). The concept behind the requirement for speed was that a battleship squadron with a speed of some 7.4km/h (4 knots) greater than the main fleet would be able to pursue and outmanoeuvre an enemy fleet and force it into battle.

On commissioning, Queen Elizabeth was immediately deployed to the Mediterranean Fleet and supported the Dardanelles landings from February to May 1915. Returning from that ill-fated venture, it joined the Grand Fleet after Jutland and was flagship from 1916 to 1920. From 1920 it was flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, then from July 1924 of the Mediterranean Fleet. In 1926–27 it underwent a major conversion following which it returned to the Mediterranean Fleet until 1929, when it was briefly flagship of the Atlantic Fleet, but within a year was back in the Mediterranean.

Between August 1937 and January 1941 it again had a major modernisation in Portsmouth, completed at Rosyth (see boxed text), and after a short attachment to the Home Fleet was sent again to the Mediterranean in May 1941. It was severely damaged at Alexandria on 19 December, along with its sister ship Valiant, by an intrepid attack from Italian midget submarines. After temporary patching-up it went to Norfolk, Virginia, for a complete repair, returning to the UK in June 1943 to again join the Home Fleet for a few months before being sent to the Far East, arriving at Trincomalee (Sri Lanka) on 28 January 1944 as flagship of the Eastern Fleet.

A period of intense activity followed, as escort and support ship for carrier operations and landings in the Indonesian archipelago, followed by a refit in Durban, South Africa, in October–November 1944. It then returned to the Indian Ocean for further service, including giving cover for landings on Ramree and action against Japanese-occupied Burma and Sumatra. On 12 July 1945 it returned to Britain and was placed on the reserve list in March 1946. Stricken in June 1948, it was scrapped in the same year.

Refitted warship

One rather anachronistic feature of Queen Elizabeth was a stern gallery, reminiscent of the old wooden men of war. Over the years, and especially between 1937–41, many alterations and additions were made to all ships in the class, substantially changing each vessel’s profile. By 1942 only the hulls and the heavy guns remained unchanged, though the guns could now elevate to 30 degrees. New machinery was installed and a single large funnel mounted with a searchlight placement at its after edge.

The bridge structure was raised and enlarged to accommodate improved navigation and fire-control systems. Tripod masts were fitted fore and aft on Queen Elizabeth, an aircraft hangar and launching cranes were installed abaft the funnel, and a large number of 20mm (0.79in) AA guns were installed. Side armour alongside the 381mm (15in) magazines was strengthened to 102mm (4in). The number of 152mm (6in) guns was reduced to four on each side and the torpedo tubes were removed.