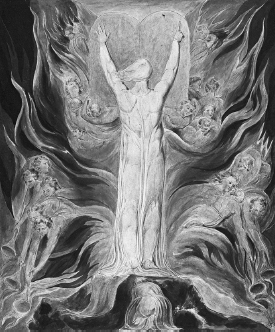

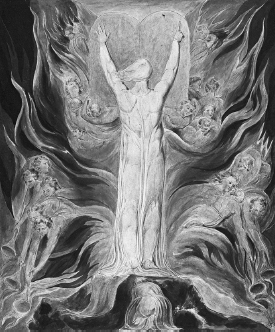

William Blake, God Writing upon the Tablets of the Covenant

For he said, I have been a stranger in a strange land.

EXODUS 2:22

The second book of the Bible is the tale of a journey. Exodus tells how Moses led the enslaved Children of Israel in a march out of Egypt, across the seas and the deserts, through starvation and revolt, to Canaan’s side. There they found the homeland promised long before to Abraham. On the way they received the Tablets of the Covenant and the Ten Commandments and built a Tabernacle to ensure that God would dwell with his chosen people for ever.

The story, with its ten plagues, the death of the firstborn, the parting of the Red Sea, and the burning bush is among the most familiar in scripture but unlike some of the Good Book’s other tales is not matched by any evidence that the events recorded ever took place. If they did, the emigrants would have made an impressive sight, as six hundred thousand Israelite men of fighting age and their families – around two million people – marched, with their livestock, across a hostile landscape. They paused several times on the way (and one camp lasted for forty years) until the next generation was at last allowed to proceed to a land that flowed with milk and honey.

When such a Great Trek might have been, if it happened at all, is just as uncertain. Some rabbinical scholars place it at 1313 years before the birth of Christ. Others argue from historical data that it took place three hundred years earlier. Many of the sites named in the Bible as way-stations were first occupied much later than that and Pharaonic records have no mention of such a dramatic episode, which would have reduced Egypt’s population by half.

When the Children of Israel entered the Promised Land they found it populated by alien races. They were enjoined to destroy them. The Lord had said: ‘For mine Angel shall go before thee, and bring thee in unto the Amorites, and the Hittites, and the Perizzites, and the Canaanites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites: and I will cut them off . . . And ye shall dispossess the inhabitants of the land, and dwell therein: for I have given you the land to possess it.’ The migrants, says Exodus, obeyed those instructions to the letter. In truth, some of the cities said to have been demolished did not then exist and the relics found in Canaan itself show no sign of an explosion in numbers when the alleged multitude arrived. They suggest instead that Judaism grew within that decaying nation’s own boundaries.

The history of the Bible’s second book is itself disputed. It appears to be an edited version of earlier documents brought together half a millennium before the Common Era by exiles in Babylon who wished to emphasise an identity separate from that of their captors. It was as much a political symbol as an account of real events. The Book was written to preserve the tale of a tribe whom God had identified as a ‘stiffnecked people’, a race set stubbornly apart. It binds this chosen group – the sons and grandsons of Abraham – to a supreme deity, gives them a unique status in his eyes, and provides them with an eternal home.

Since those days, the history of the Jews has been one of invasion, occupation, expulsion and exile from one country after another. That has, for many, led to a hunger to return to the Promised Land, the biblical kingdom where they have their roots. They are enjoined to do so in the memorable words of the Psalms: ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth.’

The story of the Exodus is still a potent symbol and the Middle East is now torn by argument about the legitimacy of the state that claims to descend from the exiles. Its emergence involved repeated conflict, and the war goes on. Just before it was established, a band of displaced European Jews travelled to Palestine from France aboard a battered steamship, the Exodus 1947. The vessel was blocked by the British, who were desperate to avoid a repeat of the Arab riots that had followed an earlier wave of immigration, but its failure to make the shore was a propaganda coup for the Zionists and in time most of its passengers found their way to the new state by other means.

The claim of a God-given territory has been just as contentious in other places. Herman Melville wrote in Moby-Dick that ‘We Americans are the peculiar, chosen people – the Israel of our time, we bear the ark of the liberties of the world.’ Two centuries before his day, the Puritans saw their own flight from the Old World as an equivalent to the escape from Egypt. Their legal code was based on the Bible: ‘The Word of God shall be the only rule to be attended unto in organizing the affairs of government in this plantation.’ For them, Thanksgiving was equivalent to the Day of Atonement and the nation which emerged from their efforts still holds reminders of their creed. Yale bears on its insignia an image of the breastplate of the High Priest of the Temple, while the first version of the Great Seal of the United States showed the Jews about to cross the Red Sea (the story that Hebrew might have been adopted as the nation’s official language is, alas, apocryphal). In fine biblical tradition, the Puritans – those chosen people – persecuted members of other sects as soon as they had a homeland of their own.

Concrete evidence about the origins of the Jews is fragmentary at best. Their shared pedigree emerged from the ruins of Canaan, Israel’s decayed predecessor, which occupied the coastal plain and stretched into the hills to include Jerusalem. By the Late Bronze Age Canaan was in decline. As time moved on and iron replaced bronze, the state began to break apart. Schismatic groups started to demand a separate existence. The bones of pigs are found in the remains of many Canaanite sites, but in time they disappeared from middens in the highlands, perhaps as evidence of the emergence of a new culture. By the late Iron Age those villages had much increased in size. Soon, the Israelites were a political entity and by a thousand years before Christ were in a more or less permanent state of war with their neighbours, and – now and again – within their own ranks.

Sometimes they won, but quite often they did not. In around 1000 BC David is said to have reigned in Jerusalem over a nation that united the northern kingdom of Israel with the southern state of Judea but no generally accepted evidence of his court has been found, although substantial remains show that the city was by then an important centre of administration. The two Books of Kings detail the endless quarrels and reconciliations between the Lord and his chosen people as the latter turn, again and again, to false gods. The divine being punished the apostates without mercy: ‘Behold, I am bringing such evil upon Jerusalem and Judah, that whosoever heareth of it, both his ears shall tingle . . . and I will wipe Jerusalem as a man wipeth a dish, wiping it, and turning it upside down.’

To show his displeasure, in 722 BC the Lord enabled the Assyrian potentate Sargon to smash up the northern kingdom’s own capital and expel its inhabitants. Two hundred years later came the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar, who destroyed the Temple in Jerusalem and shattered its adherents’ confidence that God had chosen the place as a permanent home. Many Jews were exiled to Babylon itself. On their return after the victory of the Persians in 539 BC they brought with them a purified and strengthened confidence in their own creed. Soon they built the Second Temple and promoted symbols of identity such as circumcision. The Persians were in the fullness of time defeated by Alexander the Great and for a period the Nation of Israel fell under Greek influence. After a variety of internal upheavals and schisms the Romans took power and appointed Herod as the leader of the local province. That led to revolt and to a revenge of the conquerors, who destroyed Jerusalem, most of the Second Temple included. Many of the city’s natives fled.

Such upheavals led to the emergence of new Jewish communities to add to those already present around the Mediterranean. Others were scattered as far to the east as India and even China. Legend chased the Jews across the globe and various African tribes are said by some to be their kin, perhaps the descendants of the Lost Tribes. Much of this is fantasy.

Some of the exiles were lost from sight, some kept to their ancient practices in an alien nation, and some managed, much later, to return to what they still viewed as their Promised Land. Their history is full of gaps and has become confused by exaggeration and myth, but now the double helix has followed the family tree of the Children of Abraham to its roots in Africa, to its trunk in the Levant and along its many branches to the ends of the Earth.

Sometimes the molecule confirms the tale set forth in the Bible, but often it does not. Whatever its complexities, the Jewish past as revealed by science has a message for the whole world; that throughout history, humankind has suffered exodus after exodus. DNA also shows that Homo sapiens has again and again been on the edge of extinction, with bands of pioneers in flight across a perilous landscape in search of a new home. Our genes tell of exile, loss and disaster. They speak in addition of the universal power of sex even in the face of those who try to keep their chosen peoples apart.

The sole survivors of the biblical deluge were a husband, a wife, their three sons and their spouses. From those few loins sprang, some say, today’s multitudes. Should they be right, modern humankind would be reduced indeed. Any population that goes through a bottleneck pays a penalty, for it loses diversity as the genes of those who do not survive disappear into the grave (or the deeps). After the Ark’s arrival on Ararat, just ten copies of the double helix – two from Noah, two from his wife, and six from the three spouses of his sons – were left to populate the globe. Such an event would have led to the random loss of certain variants and to great shifts in the incidence of others.

Exile, isolation and loss are still powerful themes. The only eighteenth-century English novel much read today tells the story of another shipwreck. Its sole survivor finds a new insight into the sacred and gains a sense that a sojourn in the wilderness has changed his life.

Daniel Defoe’s tale is based on a true story. The island of Juan Fernández, three hundred miles off the coast of Chile, was renamed fifty years ago by a publicity-conscious government as Robinson Crusoe Island. There, in 1704, the Scot Alexander Selkirk demanded, after a quarrel with his ship’s captain, to be marooned upon its deserted shores. He managed to survive on the flesh of feral goats and lasted for four years until he was picked up by a vessel whose commander described him as ‘a man Cloth’d in Goat-Skins, who look’d wilder than the first Owners of them’. Once back in England Selkirk gave an account of his adventures to the Spectator. It aroused much interest and in time was used by Defoe as the basis of his novel Robinson Crusoe. That work has remained a best-seller to the present day.

Defoe’s hero bemoans the fact that he had, for most of his stay, no more than a parrot to talk to, while Alexander Selkirk himself recited biblical verses to keep alive his ability to speak. Language connects us to the human race. Crusoe’s first task when he came across Man Friday was to teach him English (that done, he converted him to Christianity). The intelligent savage picked up both talents with remarkable ease, but not all of us are so lucky, for some people find it hard to deal with speech. Infants with ‘specific language impairment’, as the condition is called, find it hard to compose complete sentences or even to pronounce simple words. Some of the many variants of the condition have a genetic basis. In most places, around one person in a hundred has the problem, but a third of the six hundred inhabitants of today’s Robinson Crusoe Island are affected, more than anywhere else in the world.

The island stayed empty for a century after the departure of Alexander Selkirk and in time became a penal colony. It was abandoned after a revolt by the prisoners, but was repopulated after 1877 by a small group of stragglers from Chile itself.

Its language problem comes from an accident of history not unlike that faced by the descendants of the Ark. All those who have inherited the condition descend from one of two brothers among the founders, one of whom must have carried the gene responsible. Today’s problem is the legacy of an ancient biological mishap; a rare gene which suddenly became common because it was by chance borne by a single member of a small group that later much increased in number.

Many places cut off by oceans, by deserts, by mountains or by social barriers have had such an experience of exile followed by isolation. Often they have a high incidence of otherwise rare genes (some of which cause inherited disease) which have, as on Juan Fernández, become more abundant through simple accident. A huge new survey of variation in the DNA of a thousand people across the globe shows that most populations share the same set of frequent variants, but that the many rare versions are usually confined to one region or ethnic group as a further hint of the random actions of the hand of history in a small and cut-off population. Sometimes, as on Robinson Crusoe Island, the written and the biological records complement each other, but in most places the tale told in the double helix is all that is left.

The Jews themselves show the power of random change. The Ashkenazim are now the largest group and comprise around eight tenths of the world total of fourteen million. The contrarian author Arthur Koestler claimed that they were scions of the Khazar Empire, which for a time dominated Georgia and Southern Russia. In the eighth century, in an attempt to unify its peoples, its aristocracy did indeed adopt Judaism (although that did not last long). Romantic as Koestler’s notion might be, Ashkenazim have few connections with the Caucasus. Their immediate ancestors started their European journey in Italy. A few then settled in the Rhine Valley and, around the tenth century, began to move further into what is now Germany, and eastwards into the rest of Central Europe. There the population exploded, from fifty thousand in the fifteenth century to two hundred times as many by the end of the nineteenth.

The Ashkenazim have a history more remarkable than that imagined by the author of Darkness at Noon. On the journey up the Rhine, as on that from mainland South America to Robinson Crusoe Island, a moment of near-extinction left a permanent mark. Their mitochondria went through a bottleneck almost as severe as that at the time of Noah. Around half of today’s Ashkenazim share descent from just four women, the number on the Ark. The molecular clock of mutations hints that the quartet lived in around the twelfth century. That accident of history still resonates in the health of their descendants. They have rather high frequencies of around twenty otherwise rare inherited illnesses (such as the nerve disorder Tay-Sachs disease, carried in single copy by one in thirty among them, ten times its incidence in the general European population). By simple chance, one or more of those few female founders may have carried hidden copies of those errors that spread to thousands as the population grew. The mutations that lead to inherited breast cancer are also almost identical among Ashkenazim, for just the same reason. A moment of demographic near-disaster dictated the future for millions.

Other exiles from the Promised Land can trace their descent to even smaller numbers of women. Half the Mountain Jews of the Caucasus descend from a single female, as do many among the communities of Mumbai and of Cochin (now known as Kochi) in India.

On the global scale, too, patterns of DNA variation show that the pilgrimage of men and women, whatever their religious affiliation, from their native Africa to the ends of the Earth must have involved whole fleets of allegorical Arks. Some of the vessels made it to safety and those on board flourished in a new homeland. Many more must have foundered before they reached a refuge, with the loss of all hands, and all genes. The most remote places have less diversity than our native continent as a result.

We live in an age of fecundity greater even than that of the Israelites in Egypt. In their day the world held, at a guess, fifty million people. Then numbers began their inexorable rise. They took from the Big Bang (or, for literalists, since the day of the Flood) until 1927 to reach two billion, until 1974 to multiply that figure by two, and until 1999 to add yet another two billion. Nobody before the twentieth century had seen the human population double, but today’s octogenarians have seen a threefold increase. The year 2011 saw the seven billionth baby. Today’s growth rate is half that of the 1960s, but a new France still arrives each year. Numbers will peak at around ten billion in 2100.

Huge as that figure is, patterns of inherited variation show that the whole human population is still in recovery from a series of ancient disasters and that, for much of the past, Homo sapiens was an endangered species.

Chimpanzees hint at what a hard time our ancestors must have had when they set off on their global journey. The animals’ present plight is dire. Just a century ago two million chimps lived in Africa but now they are reduced to less than a tenth of that number and may be gone from the wild within a century. Even so, in terms of diversity, the two primates are mirror images. Since the split from their common ancestor with ourselves some eight million years ago, chimpanzees have retained far more variation than have humans. That hints at an ancient population bottleneck. We also possess vast numbers of individually rare genetic variants as further evidence of an ancient Crusoe experience: a population explosion from a tiny base as recently as five thousand years ago, not long before the earliest events recounted in the Bible (and close to Archbishop Ussher’s estimate of the date of the Creation). The genes show that chimpanzees have always been rather common while men and women, in spite of today’s profusion, have flirted with extinction again and again. Whatever our present billions, averaged over the past half million years or so, our own population has in effect been no more than ten thousand, that of a small town today.

As humans filled the world the general picture was of moderate abundance – perhaps hundreds of thousands – in some places, but punctuated by severe reductions as bands of pioneers moved to new and empty lands. Our expansionist urges have made us into a diminished primate.

Humans of modern form left Africa rather more than a hundred thousand years ago, several tens of thousands of years after they first appeared there. Because of the cold they did not make much progress until around sixty thousand years later, by which time they had reached western Asia. Australia was settled ten thousand years after that and the first known Britons of modern form (who chose to live in Torquay) did not arrive for another ten millennia. New Zealand remained uninhabited until around AD 1250, and some of the remote Pacific islands were empty until just a few centuries before the present.

The biblical tale of an ancient group of pioneers has an echo in reality. Comparison of the DNA of modern populations on the flight from their roots in Africa, from there to Europe and to Asia, and onwards to remote islands such as Tahiti or New Zealand, shows that, on every step of the journey, more and more diversity was lost as proof that very few people made their way to each of those new-found lands.

Twenty-five years ago, with the help of a young Iranian physicist, I made the earliest (and entirely forgotten) attempt to work out the size of the first bottleneck on the global journey; that out of our native continent. We had information on just a short length of DNA sampled both within Africa and outside it and used the figures to calculate how small the emigrant population must have been to enable the accidents of sampling to cause the observed drop in diversity. We came up with the remarkable result that just one couple might have made the first exodus. The total would be larger if the emigrant group stayed small for many generations; for example, six individuals for two hundred years would have the same effect. By coincidence, that is just the same number as there were passengers on the Ark. Now, with information on a quarter of a million sites across the DNA in far more people and with a much more refined analysis, the figure for a single generation has, in an another reminder of the Genesis story, risen to six.

The journey from our homeland got off to a difficult start. The experience was repeated again and again as small bands struggled onwards to the coasts of the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean and the eastern shores of Asia.

For all that time a land without people was waiting. Twenty thousand years ago, men and women began at last to stray into Melville’s Ark – the Americas – from Siberia. In time they filled its twin continents, but for thousands of years its peoples were cut off from the world. Then, everything changed. On October 12th 1492 Spanish ships anchored off an island in the Bahamas. Those vessels, and the many that followed, brought waves of European and African genes to the New World. In an evolutionary instant, what had been a remote and reduced outpost of humankind became a microcosm of what the future holds for us all.

The Jesuit José de Acosta spent most of his life in Latin America and crossed the continent again and again. In his 1590 book The Natural and Moral History of the Indies he remarked upon earthquakes and the tsunamis that followed them, studied altitude sickness in the Andes and described how the locals used cocaine. On his travels, which took him to Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Mexico, the priest noted the physical similarity of the natives to the peoples of the Far East. De Acosta came up with a radical suggestion: that the first Americans had migrated from Asia across a land bridge, now submerged.

He was right. Apart from the few stragglers who made it, much later, to distant places such as Tahiti, Hawaii or New Zealand, the entry into the New World was the final major step on mankind’s exodus from Africa.

The Bering Strait – once the Bering Land Bridge – was not discovered until more than a century after de Acosta’s death. The place is named after the Danish navigator Vitus Bering who had been hired by the Russians to survey the Kamchatka Peninsula at the eastern extremity of Siberia. He sailed through the Strait in 1728 and died there on a second expedition a few years later. Its waters are in places no more than thirty metres deep. In a parallel to the parting of the Red Sea, as the ice sheets grew they fell away altogether, to offer a passage to a band of emigrants.

At the time of the last great freeze, with sea levels a hundred metres lower than now, Beringia was a vast plain a thousand kilometres wide. For much of its history it was a cold, dry and hostile steppe. Now and again sparse forests of birch and poplar sprang up, but the Bridge was a hungry place. Mammoths and sabre-toothed cats roamed the landscape as did a few scattered bands of hunters, who ate what they could kill and moved back and forth between what is now Alaska and Siberia. Around seventeen thousand years ago, a few ventured further into the Americas.

As the world warmed, the waters returned, to give the first inhabitants of the Americas a reduced version of their own Great Flood. The isthmus began to shrink until, around fourteen thousand years before the present America broke its ties with Asia, the people on the eastern shore found themselves on a new continent, marooned between a stormy ocean and a great range of mountains.

Soon, the ice retreated further. The glaciers of the Canadian Rockies shrank and opened a corridor from Alaska into the Great Plains. Another escape route was provided by the narrow plain that still lay along the coasts of Alaska and of British Columbia. Each was a door to a treasure-house beyond. The immigrants trudged onwards, and reached the continent’s southern tip within three thousand years.

Almost no relics of that earliest occupation have been found, but a fourteen-thousand-year-old site in Central Texas called Buttermilk Creek has yielded a mass of simple tools, not much different from those then made in the Old World. Buttermilk society was supplanted by the first genuine American culture, the Clovis people (who are named after the town in New Mexico where their vestiges were first found). Their remnants date from around eleven thousand years ago and are scattered across the Great Plains and the southern United States, and their way of life has been identified in Mexico and even further south. Most Clovis sites are in the east rather than the west, evidence that a wave of travellers moved towards the Atlantic coast before they began the trek towards Cape Horn. Their economy lasted for thousands of years. Shaped stones were used as blades and as arrowheads. Using spears launched with throwing-sticks they killed off the mammoths, bison and other large mammals that once roamed the continent.

Once arrived in the grim landscape of the far south the immigrants must have lived in much the same way as did their descendants, the Fuegians as Charles Darwin called them on his visit in 1832. The Yaghan people (to give them their correct title) wore almost no clothes, and survived the bitter cold in small groups huddled around fires (a habit which gave Tierra del Fuego its name). Darwin thought them to be ‘miserable, degraded savages’ and wrote that ‘I could not have believed how wide was the difference between savage and civilised man: it is greater than between a wild and domesticated animal, in as much as in man there is a greater power of improvement.’ Be that as it may, the southern tip of Patagonia has a higher density of archaeological sites than anywhere else on Earth, as evidence of a sophisticated and successful ancient society (and Darwin later moderated his contempt).

The New World was a place of small, mobile and isolated bands. The shortage of relics hints at how sparse its peoples must have been. Biology, too, provides evidence of how few made it to their new-found land and of how even fewer struggled towards the final steps of the journey.

American skeletons are less variable than are those of their African or Asian ancestors. Two Native Americans from the same place hence look more like each other than do two people from other parts of the world. In an unexpected echo of the past, the bacteria in their guts are also less diverse than those found in Old World intestines, as a further hint that the internal fellow-travellers suffered a collapse as they passed through bottleneck after bottleneck. Their languages, too, speak of difficult times. Each of the globe’s idioms consists of a series of distinct sounds. Their numbers vary from place to place. Africa is the world capital, with a remarkable range of clicks, tonal changes, whistles, guttural noises and so on. English is reduced in comparison, while the native tongues of the New World are even more diminished. At the southern tip of the continent, where Darwin remarked (unfairly) that ‘The language of these people, according to our notions, scarcely deserves to be called articulate’, speech is at its most truncated.

The best evidence of how hard the journey to – and through – the new continent must have been comes from the double helix. There is a hole in the data, for many Native Americans in the United States have refused to cooperate as they prefer to hold to their traditions of a miraculous emergence on their own territories. Even so, the genes tell the remarkable tale of the first entry into what, long afterwards, became a Promised Land for much of the rest of the world.

To reach its empty landscapes the escapees from Africa were forced, like their biblical descendants, to cross deserts and to climb mountains and to make great detours, not around the mountains of Sinai and the Red Sea, but around impassable obstacles such as the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean. A comparison of today’s genetic variability in populations from across the globe with the walking distance from Addis Ababa reveals a good fit between the two, with the peoples of the most distant places much less diverse than those who stayed close to home. The natives of South America are the most reduced of all, with a quarter fewer single-letter differences in the DNA than found among sub-Saharan Africans. Their impoverished state shows that the continent’s founders were few in number even when they arrived in Alaska, and lost yet more diversity on the rocky road to the south.

Beringia was America’s Ark. The genetic shift in the Americas compared to the Old World suggests that the native population of the whole continent, North and South, descends from fewer than a hundred people. The double helix binds most of today’s Native Americans not to Siberia but to the peoples of Kyrgyzstan and the Buryat Republic, thousands of kilometres away. Those remote nations share more ancestry with Americans than do today’s Siberians, perhaps because of movement within Asia since the days when the pioneers struck to the east.

After the first wave of colonisers, immigrants continued to trickle into the New World. The natives of the Aleutian Islands speak a language distinct from other Native Americans and have genetic ties with Siberians and also with Greenlanders, who may have spread there from Alaska across the far north (an idea supported by the five-thousand-year-old frozen corpse of a Greenland Inuit, which shows closer affinity to Siberians than to other inhabitants of the Americas). Canada’s Chipewyan Indians are yet another group for they have ties with the ancestors of today’s Han Chinese.

Y chromosomes lose variation on the road to the south faster than do other segments of the double helix. The leaders of the Aztecs and the Mayas were as avid for intercourse as were their Old Testament equivalents. A primary wife provided them with official heirs, but they were allowed many secondary partners. Some fathered enormous families. As a result other males – because they were sacrificial victims, were killed in wars, or were too poor to attract a mate – had no children at all. Their DNA was at a dead end, which meant that the bottlenecks bore more upon men than upon the opposite sex.

For Native Americans, male and female, the arrival of the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa María marked the end of ten thousand years of solitude. The once empty continent changed for ever. Men and women poured in from across the globe. They brought not a trickle but a torrent of DNA. The post-Columbus clash of ancient with modern put paid to mankind’s long era of random change. The peoples of the Americas began to merge with the invaders until their adopted landscape became the most diverse continent the world has ever seen. Now, the whole planet is on the edge of an age when admixture is all.

The Spaniards, like those who had made the Exodus from Egypt, believed that they were on a mission to a land destined by God to be their own. Columbus himself had quoted an apocryphal book of the Bible in his attempt to persuade the nation’s rulers to finance an expedition to India with a journey to the west. The voyage was an attempt to fulfil Isaiah’s prophecy that, to complete the diaspora and bring about the Second Coming: ‘Surely the isles shall wait for me, and the ships of Tarshish first, to bring thy sons from far, their silver and their gold with them.’ Tarshish was, in this view, a mystic city in Ophir, in the Far East, and Columbus was influenced by the hope of an era of bliss – the recapture of Jerusalem for Christianity included – that would emerge when the Word of God had at last reached that remote spot, and had filled the world. The riches that awaited him (‘Then shalt thou lay up gold as dust, and the gold of Ophir as the stones of the brooks’) would pay for the rebuilding of the Second Temple.

On arrival in what they still saw as an outpost of Asia, the Spanish conquerors denied even that the local Indians belonged to the same species as themselves. They could, like the Perizzites, Canaanites, Hivites and Jebusites of old, be killed with a clear conscience, to allow God’s will to triumph.

José de Acosta disagreed. He championed the notion that Amerindians should be regarded as human even if he did feel that they were ruled by Satan in the form of their own murderous gods. After much persuasion the Conquistadores admitted as much but that did not stop the slaughter. Columbus said of the Taino people of Hispaniola that they were ‘innumerable, for I believe there to be millions upon millions of them’. The true figure was several hundred thousand, but within half a century just a few hundred were left, the rest worked to death in the new gold mines, or killed off by infectious disease. The first great epidemic – perhaps influenza – struck just a year after the Europeans arrived. Pestilence travelled faster than did soldiers, who, as they moved further into the continent, encountered peoples already almost destroyed. The population of Central America fell from twenty-five million in 1518, the year before Cortés began his conquest of the Aztecs, to seven hundred thousand a century later.

Some silent witnesses hint at how many must once have lived in the transatlantic Canaan. Large parts of South America now impenetrable were not temples to untamed wilderness, but open landscapes that buzzed with activity. The Atlantic forest of Brazil, at the time of Darwin’s visit a dense jungle, had once been burned every few years by its inhabitants. The evidence lies in the carbon deposited on the floors of nearby lakes. Much of the Amazon rainforest is also new. Before Cortés, the landscape was scattered with villages, the country farmed with care. Banks and ditches hundreds of metres across and approached by long avenues remain. Together they supported millions. After the collapse of the human population they disappeared under rampant vegetation.

As the devastation went on, more and more migrants were pulled – or pushed – into the New World. Bartolomé de las Casas in his A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies of 1542 claimed that the Indians were unsuited to hard work and that they should be freed from slavery. They were – but they were replaced by Africans. The earliest arrivals from that continent landed on Hispaniola in 1501, less than a decade after the first Europeans. In the next three and a half centuries, twelve million joined them (which meant that four times as many people with black skins immigrated in that period as did those with white). Only a minority were taken to the United States while almost all the others went to the Caribbean and to South America.

Sex started at once, and involved all parties. Many of the Europeans who colonised Hispaniola married local women. Cortés himself impregnated a princess and had several other half-native children, one of whom even found a place in Spanish society. Pizarro, too, had children by members of the Inca nobility and, no doubt, many soldiers entered into their own engagements. From the first days of the European arrival the imperatives of biology spilled over the social barriers. That history has a reflection in modern Spain: if one of the Spaniards whose DNA was read off in the global survey of DNA variation across a thousand genomes has a variant shared by just one of the others, there is a 50 per cent chance of that second individual living in South America, as proof that genes crossed the Atlantic from west to east as well as in the opposition direction.

In the New World itself, there was (and still is) a certain status associated with an individual’s racial background. Parts of that continent had for many years a taxonomy that classified people by their genetic history, as ‘wolves’, ‘Moors’, ‘those suspended in air’, and other fine distinctions, with prestige dependent on how many European ancestors any individual could claim. Modern Colombia is a microcosm of that process. Nine out of ten of its inhabitants identify themselves as of mixed ancestry, while most of the rest think of themselves as displaced Africans. No more than a tiny proportion claim to be Native American.

The nation’s genes reveal a more subtle blending of DNA. As was the case for the Cape Coloureds, admixture by men and by women was less than even. 90 per cent of the mitochondrial lineages of Colombian cities are of Amerindian ancestry while fewer than one in twenty comes from Europe. Almost half their Y chromosomes, in contrast, have a European origin, as a reminder of the sexual habits of powerful men. Everywhere, the real proportion of European genes in its inhabitants is much higher than that obtained by asking people what group they feel they belong to, for in Colombia, as in other places, mixed-race people with rather dark skins tend to over-estimate their African ancestry (Condoleezza Rice professed herself astonished when she learned that more than half her heritage comes from Europe). She and many others place more weight than it merits on the small set of genes that determine physical appearance.

In the five short centuries since the Europeans arrived, the New World has, thanks to the power of lust, moved from its status as the most diminished branch of the human kindred to its most diverse. The desire for sex has overcome the barriers of colour, culture and creed to brew up a rich biological soup.

That history of gene exchange among groups once defined as utterly distinct has a resonance in the biblical Exodus. Those ancient travellers to a Promised Land were – like the Conquistadores – admonished to keep themselves pure in spirit and in behaviour, and to avoid liaisons with members of lesser tribes (‘. . . the LORD, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God: Lest thou make a covenant with the inhabitants of the land . . . And thou take of their daughters unto thy sons, and their daughters go a whoring after their gods’).

The Children of Abraham, like those of Columbus, did not live up to expectations. They began to stray almost at once. Ezra (who lived in the fifth century BC) was outraged: ‘The people of Israel, and the priests, and the Levites, have not separated themselves from the people of the lands, doing according to their abominations . . . so that the holy seed have mingled themselves with the people of those lands . . . And when I heard this thing, I rent my garment and my mantle, and plucked off the hair of my head and of my beard, and sat down astonied.’

The Prophet’s fury was justified. The double helix shows that the history of his people has, from its earliest days, been tangled indeed, with evidence of exile, return, shifts of identity, and copious admixture with those who surround them. Just as in Melville’s ‘Ark of the liberties of the world’, the inhabitants of the many new Jerusalems that sprang up across the globe indulged in plenty of sex with the neighbours.

The habit began in the earliest days. In Judaism membership is passed down the female line and although conversion is possible the process is arduous. Most modern Jews have a Jewish mother but the mitochondria tell a more ambiguous tale about how long, and with what rigidity, that rule has been upheld. The Beta Israel – the Black Jews of Ethiopia – are African in appearance. One legend suggests that their conversion may have come five centuries before Ezra, with Menelik, the son of Solomon (and perhaps of the Queen of Sheba), the founder of the country’s main dynasty. His royal lineage lasted, after a convenient shift of allegiance to Christianity, until the fall of Haile Selassie in 1974. Some claim instead that the Beta Israel emerged from a migrant band of wanderers, perhaps the Lost Tribe of Dan, or even from Christians who objected to the doctrines of the Ethiopian Church and converted to Judaism within more recent times.

Genes show that the Jewish invaders exchanged more than ideas with the Ethiopians. Beta Israel mitochondria resemble those of other Ethiopians, while their Y chromosomes have a tie to modern Jews. The Beta Israel descend not from immigrant women, nor from recent mass conversion, but from Abyssinian females who entered into relationships with the intruders. In spite of initial disagreement as to whether these Black Jews had the right of return, in 1991 there was a huge rescue mission to fly them to Israel.

Such exchanges with non-Jewish populations have gone on within Israel, and across the world, throughout the centuries. Many of their lineages resemble those of non-Jews as evidence of a long history of admixture.

Ezra was particularly outraged that the hereditary priests of the temple should have liaisons with members of other faiths. The genes show that he was right to be annoyed. Around half the cohanim, whose surname identifies them as descendants of the temple priesthood, do share similar Y chromosomes as proof of common ancestry but the rest have an assortment of such things from other males who have sneaked onto the pedigree.

On the larger scale, the picture is just as confused. The DNA of Jews from Western Europe (Ashkenazim included), and from Iran, Iraq, Syria, Italy, Turkey and Greece, reveals some shared links with the Middle East but also has strong ties with that of the non-Jewish peoples amongst whom each has dwelt. European and Syrian Jews taken together show a modest divide from those from the modern Middle East. The Jews of the northern and southern shores of the Mediterranean both trace their origin in part from their fellows who left Israel in Greek and Roman times, but many on the European side have quite close kinship with Italians. That may be in part due to intermarriage, but conversion is also involved for at the time of the Classical occupations of the eastern Mediterranean thousands of pagans abandoned their earlier practices to take up Judaism. Iranian and Iraqi Jews, who claim descent from the Babylonian exiles, have rather fewer alien genes than others, as proof that their diaspora was truer to its roots than most, but the general picture is one of assimilation.

As their numbers grew, the Children of Abraham moved on. The city of Tarshish was probably – in spite of Columbus’ belief that it was in the Indies – in southern Spain (Jonah was on his way there when he was swallowed by the whale). There, long ago, settled another branch of the Abrahamic household. The Sephardim, as they were known, began to arrive at the time of the fall of the First Temple from the biblical Sefarad (which may have been Sardis, capital of Lydia, now part of Turkey). Many more moved to Iberia after the Roman conquest of the Levant.

As the Visigoths, the Germanic people who ruled the peninsula in ancient times, took up Christianity, discrimination against the Sephardim increased until, in the end, non-Jews were forbidden even to speak to them. Many left for North Africa. Then, in AD 711, came the Muslim invasion of Spain. Some of the Jewish exiles in the Maghreb welcomed the chance to return to Iberia and as Islamic rule moved onwards Jews took over the government of certain towns (a fact later used as an excuse for persecution). Under the new regime they flourished as bankers, physicians, merchants and the like. Their numbers increased to almost half a million, with plenty of marriages outside their own community, to such an extent that even Ferdinand II, who authorised Columbus’ voyage of discovery, had Jewish ancestry (although it was not prudent to point this out).

Soon the situation changed, once again, for the worse. Fundamentalism grew among the Islamic invaders, who began to bully all non-believers. Some among the Sephardim moved to a more tolerant Portugal, or left Iberia altogether. Then came a further triumph of bigotry and, for the remaining Jews, disaster. The Christians fought back against the North African invaders, and won. On the final defeat of the Muslims the fate of the Sephardim was sealed. In spite of his own family history, Ferdinand II, supported by the Church, issued a decree that demanded their immediate conversion or expulsion. Some Jews were burned at the stake, many more left, while others converted, or at least appeared to do so. Thousands fled, some back to Africa and more to the Ottoman Empire, where they were welcomed as merchants and as people of education. They were the kernel of much of the modern Jewish population of Greece and Turkey, which still has biological links with the opposite end of Europe.

In Spain and Portugal, most of those who remained claimed to accept Catholicism. Often that was no more than a gesture that allowed the conversos, as they were called, to keep their place in society while in private they continued to follow their own credo. The secret Jews were hunted down by the Inquisition who identified them through careful observation of their habits, such as a tendency to wear clean clothes on the eve of the Sabbath. In spite of such persecution they maintained a hidden identity for many years. In a certain Portuguese village one community of secret Jews married among themselves for five centuries, into modern times. As a result, all but thirty or so of its four hundred present inhabitants trace descent from just one woman who lived during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella.

Many conversos adopted particular surnames that allowed those in the know to continue to discriminate against them. So convinced was Rome of the dangers of non-Christian blood that it passed a law of limpieza de sangre – of purity of blood – that lasted until the nineteenth century in the army, and until the 1960s in Majorca, where no priest with a Sephardic ancestor was allowed to celebrate Mass in the cathedral.

The Sephardic contribution to modern Spain is in truth far greater than most of the country’s inhabitants, and most Jews, imagine. It shows the extent to which, however strict the authorities, admixture is impossible to control. A fifth of the Y chromosomes of today’s Spain are of converso origin and in southern Portugal the proportion rises to as much as one in three. In the land of Tarshish, the diaspora lives on in body even if much of its spirit has been forgotten.

On the 3rd of August 1492, just a day after the deadline for Jews to convert, to leave, or to die, Columbus’ ships set forth westwards. After a stay in the Canary Islands to pick up supplies, they set off once more. In the Bahamas the explorers met their first Native Americans (who could, Columbus thought, be persuaded without much difficulty to take up Christianity). From there his vessels moved on to Cuba and to Hispaniola. A year later he was back in Spain preparing for a larger expedition, supplied with priests, colonists and soldiers. The Old World was about to join the New.

Ferdinand and Isabella were as a result – and quite inadvertently – the agents of the last great step in the dispersal of the Children of Abraham, for they forced the exiles into a new continent, where they were to flourish. The laws passed by the Spanish and Portuguese for their new Christian Empire across the Atlantic banned conversos from the territory. That policy failed from its first day. Several of the crew of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María are said to have been converted Jews, anxious to escape the dangers of Spain. Luis de Torres, for example, was born a Jew and had served as a government interpreter. Columbus took him as a translator, perhaps because he thought that his expedition might encounter some of the Lost Tribes of Israel and that a Hebrew speaker would be useful (de Torres is also said to have been the first European to smoke tobacco). Not long afterwards, several of Cortés’ own soldiers were executed on the grounds that they too were conversos. Some enthusiasts even claim that Christopher Columbus himself had Sephardic roots although a DNA test of his descendants has failed to confirm the idea.

In time, many more European Jews fled across the Atlantic. By the mid-seventeenth century there were large communities in Brazil (which had the first synagogue in the Americas) and elsewhere. Two centuries passed before many made it to the United States. Recorded Jewish history there begins in 1654 in New Amsterdam, now New York, with a group of refugees who had fled from Recife in Brazil, from whence the Dutch had just been ejected by the Portuguese. At the time of the American Revolution, there were around two thousand within its borders, most of them Sephardim, and many took part in the struggle against the British. The first synagogue opened in Rhode Island in 1790 and was welcomed by George Washington, who referred to the prophecy of Micah that ‘they shall sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree’; in other words that his new nation would, he hoped, become a land of tolerance. By the Civil War the number of Jews had gone up by fifteen times. At the end of the First World War there were more than two million in the United States, most of them Yiddish-speakers from Russia and Eastern Europe. They were joined over subsequent decades by many more desperate to escape from the Nazis and, in recent times, by migrants from the former Soviet Union. In their final exodus the Children of Abraham travelled, like those in the biblical account, in millions.

They brought their credo, their culture and their genes. In time, as in Ezra’s day, they began to merge into the nation as a whole. By the 1950s in the United States more than half of all Jewish marriages were with members of other faiths or of none. People who identify themselves with that community now represent a smaller proportion of the American population than they did even a century ago and their relative numbers are set to fall further as other groups – Hispanics most of all – expand.

The story of America’s Jews is the story of us all; a tale of exile, danger, discord and separation followed, in the end, by the collapse of social and religious barriers. Many have lost their identity, and some have forgotten their roots, but the double helix reminds them of the past. Americans with four Jewish grandparents can be separated with certainty from others with a scan of a few sections of the double helix and even those with just one grandfather or grandmother from that community stand out as distinct. Within the white population of the United States there are three ancestral clusters, from north-west Europe, from the south-east of that continent, and from the Ashkenazim. A set of three hundred variant sites is enough to ascribe every white American to membership of one or more of those lineages.

Perhaps the Patriarchs (not to speak of the security guards at Tel Aviv Airport) would be comforted by the fact that DNA has revealed a forgotten Jewish ancestry for millions. It shows that the people of Israel – like everyone else – have been through adventures and disasters in the search for a new homeland that make those of the Exodus look tame. Ezra tore his hair at the antics of his fellows; but for them, as for all of us, the imperatives of biology far outweigh the demands of doctrine.