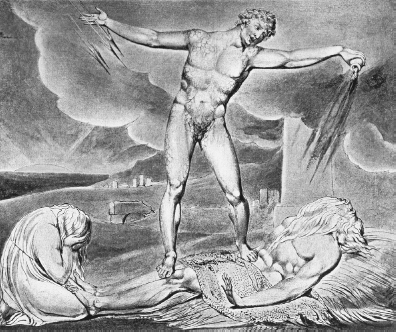

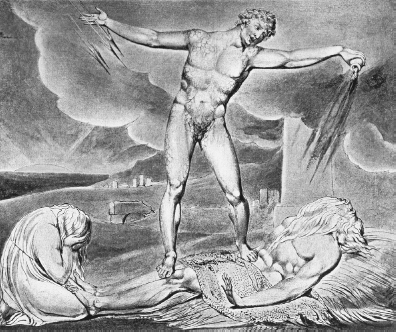

William Blake, Pestilence

To teach when it is unclean, and when it is clean: this is the law of leprosy.

LEVITICUS 14:57

After his betrayal of Jesus, in a fit of remorse Judas Iscariot returned the thirty pieces of silver to the priests and hanged himself. The priests, dubious about his tainted gift, used the cash to buy a potter’s field – a worked-out clay deposit – and offered it as a burial place for strangers and non-Jews, a role it fulfilled until the nineteenth century. The red clay gave it the name of Haceldama, the Field of Blood (although the Acts of the Apostles suggests instead that the name came from the unfortunate fate of Judas: ‘falling headlong, he burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out’).

Many of Haceldama’s tombs have been looted but some still contain human remains. One such is the burial place of a family, for the DNA from a first-century sepulchre shows that several of the occupants were related. One of the niches is walled off with plaster. It contains a shrouded male corpse, perhaps that of a priest. Molecular tests reveal the presence of the agent of leprosy. In biblical times that disease was feared above all others and was, no doubt, why the tomb was sealed.

Leviticus, the Book of the Levites, was composed over several centuries from around 1400 BC. It sets out a number of rituals designed to cope with disease. They are, in many ways, a quest for order: a realisation that, whatever its cause, illness was an insult to the system by which the Lord meant Man to live. Many of its verses are devoted to leprosy and to the rules to be followed should it be found: the presence of a ‘rising, a scab, or bright spot’ on the skin calls for quarantine and if ‘the scab spread much abroad in the skin’ the priest should pronounce the sufferer unclean. The unfortunate patient then faces exile: ‘His clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip, and shall cry, Unclean, unclean. All the days wherein the plague shall be in him he shall be defiled; he is unclean: he shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his habitation be.’

Leviticus, in that passage and elsewhere, is obsessed with hygiene. Animals were classified as clean or otherwise and any object touched by the latter group (which stretched from camels to ravens) became polluted. Sex, too, was tainted unless strict rules were followed; for a man, even to sit in a chair once occupied by a menstruating woman was forbidden and after an unexpected ejaculation he was impure for the rest of the day. A ritual wash (and now and again a ceremonial shave) was needed after handling a corpse and in other circumstances. Other passages give more practical sanitary advice: ‘And thou shalt have a paddle upon thy weapon; and it shall be, when thou wilt ease thyself abroad, thou shalt dig therewith, and shalt turn back and cover that which cometh from thee.’ Purity remained at the centre of biblical doctrine. For the Israelites, corporeal cleanliness was paramount, but in the New Testament purity of heart became the key.

Keen on hygiene as the ancient world may have been, it was in truth filled with infection. Disease is a repeated theme in the Bible (although treatment is not: almost the only cures on offer are supernatural). Some of the afflictions were unpleasant. Job complained that he was eaten alive by worms while Zechariah predicted for the enemies of Jerusalem that ‘Their flesh shall consume away while they stand upon their feet, and their eyes shall consume away in their holes, and their tongue shall consume away in their mouth.’ Most such conditions cannot now be identified although there are hints about some. Tobit, in the Apocrypha, sleeps outside by a wall in which there were sparrows, who ‘muted warm dung into mine eyes, and a whiteness came in mine eyes’ (he almost certainly had cataracts). In the same way, Jehoram son of Jehoshaphat may have had dysentery: ‘In process of time, after the end of two years, his bowels fell out by reason of his sickness: so he died of sore diseases.’

Jehoram had annoyed the deity by murdering his brothers and sisters and his plight, like that of many others, was ascribed to the anger of the Supreme Being. A whole community might be smitten: ‘Because of the wrath of the Lord it shall not be inhabited, but it shall be wholly desolate: every one that goeth by Babylon shall be astonished, and hiss at all her plagues.’ That verse was written at the time of exile of the Jews to Babylon in the sixth century before Christ, the period when the city was the largest in the world. It sucked in migrants from afar to become the first settlement to number two hundred thousand people. That link of mass movement and the emergence of a vast metropolis with infectious disease has a modern air, as the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus from the West African bush to the Congo’s new cities and onwards across the globe reminds us. The first days of the Israelites marked the start of the age of epidemics.

The leprosy of Leviticus may not have been the malady we now know by that name. Because of the opprobrium attached to the term, the condition is now called Hansen’s disease after the discoverer of the bacterium responsible. The biblical version was probably a complex of skin infections such as ringworm, psoriasis and boils. Certain lepers were said to be ‘white as snow’, which might mean that albinism (not, of course, contagious) was also involved. The matter is confused by the statement that leather, clothes and even houses might suffer from leprosy and by detailed instructions as to how they must be purified and, if that failed, should be destroyed or demolished. The term may sometimes have referred not to physical illness but to a general sense of rejection and divine displeasure, with no biological implication at all.

The notion of health as a gift and of sickness as chastisement lasted from biblical times almost to the present. Disease was a just punishment for sinners. Great plagues appeared from nowhere to strike the impure and when the correct rituals had been completed ebbed away. Most medical treatments were useless or worse and not until modern times did doctors begin to cure more people than they killed.

Medicine is now more effective than when its sole remedy was that ‘the leper . . . shall cry, Unclean, unclean’. Its progress has been spectacular. Even in the first half of the twentieth century, infectious disease was the developed world’s main cause of death. The influenza epidemic of 1918 in a single year put an end to twice as many people as AIDS has killed over the past four decades. Many of those plagues have gone (although they may, needless to say, come back).

Sewers and social progress have played a larger part in that success than has science, but scientists have at least begun to understand the origin and nature of contagious diseases. Where do they come from, why are some severe and some mild, and why is each so distinct in its symptoms? Why are certain conditions infectious and others hardly so, and why are some lethal in hours while others take years to kill? Why should sudden outbreaks happen after decades of calm and then disappear with equal speed? The biblical view of illness as conflict with the order set by God hints at a deeper truth; that all diseases are a struggle between two (or more) parties. They emerged not as supernatural punishments but from changes in our way of life, many of which took place in Old Testament times. The move from the hunting ground to the fields, from village to city, and from a lifetime in the same household to an era of mass movement each led to great shifts in the patterns of infection.

Leprosy was among the first conditions to leap onto the bacterial bandwagon. An illness that sounds much like it is recorded in the Sushruta Samhita, a text of Ayurvedic Medicine written in India around 600 BC, while skeletons show that the same disease affected humans four thousand years earlier than that. The Indian work recommends treatment with the oil of a certain tree (it also hints that suicide, normally forbidden to Hindus, was not a sin where lepers were concerned). The oil is still used by herbal healers but does not help.

The illness has an intimate relationship with man. It infects no other animal except, bizarrely, the American nine-banded armadillo (which picked it up from European immigrants and within which the bug can thrive because of its low body temperature). Until not long ago the bacillus could be cultivated only in human cells but now mice with weak immune systems and armadillos themselves are used in research.

Leprosy’s main target is the nervous system rather than (as the Levites thought) the skin. Its agent, a bacterium called Mycobacterium leprae, attacks nerves in the face, fingers, testes and other cool parts of the body. The immune system responds with a failed attempt to wall off the invaders. That leads to inflammation, to the accumulation of clumps of white blood cells and decayed tissue, and to the destruction of nerves, skin, the lung surface and more (the popular idea that fingers and toes drop off is incorrect, but they may become shorter as bones are destroyed). As time goes on, the muscles become weak, and patients lose the powers of taste and smell. A feeble voice and a ‘lion face’ are a further scourge. A few men even lose their testicles and grow breasts. Putrid flesh may generate a foul odour that defines the sufferer as ‘unclean’. Until not long ago many among the afflicted were so shamed by that label that they denied their illness and avoided treatment.

The agent of leprosy is protean in its effects and patient in its work. The average incubation time, from infection to diagnosis, is five years but in some people may be eight times as long. Its cells divide no more than every two weeks or so, and the number of bacteria present when the condition is finally diagnosed is greater than that of almost any other illness. Nine out of ten people are resistant to attack, and many of those infected are quite unaware of the fact. In spite of the Levites’ ancient terrors the condition is not very contagious. Its agent is in the main passed on by bacteria sneezed out by its bearers, while transfer by touch or from mother to foetus or to infants from breast milk plays a lesser part. There have even been cases in which, in a revenge of the armadillos, people have picked up the disease from those animals. Around eighty Americans a year are infected in this way, most of them in Louisiana and Texas, where the locals hunt, skin and eat such creatures.

Infectious or otherwise, the power of biblical injunction meant that for most of history lepers were forced ‘without the camp’. They were impressed into special colonies, or were obliged to carry horns or rattles to warn of their approach. The colonies or ‘lazarets’ (named after the infected beggar Lazarus, gathered into Abraham’s bosom) were on islands or in isolated valleys, where, quite often, those forced to live there were abandoned. In Hawaii, whence the disease was brought by Chinese immigrants, the Segregation Law of 1865 banished patients to a remote peninsula on the island of Molokai. There, chaos and crime ruled until an itinerant Belgian missionary improved matters. The place remained as a quarantine site until 1969. Japan kept its policy of isolation into the 1990s, with hundreds shut away against their will. Such was the terror of contagion that some countries printed special ‘leper money’ for fear that to allow patients to handle cash in general circulation would cause the disease to spread. A few lazarets remain, but in Europe at least their aged residents now stay on by choice. In other places, alas, that is not always true.

The Bible tells of many other illnesses. Some sound familiar; thus, Moses threatens his flock that if they do not obey the Lord’s commands he will smite them with ‘a consumption, and with a fever, and with an inflammation, and with an extreme burning’ but nobody has yet identified the Blasting, the Mildew, and the Botch of Egypt that were also used to intimidate those who broke the rules.

Perhaps plague itself – the Black Death, which brought as much terror to the Middle Ages as had leprosy to the people of ancient Israel – was among the promised tormentors. The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and is in many ways a mirror image of the bane of Leviticus.

The contrast between the two ancient tormentors could not be greater. Leprosy is – apart from the odd armadillo – restricted to man, is hard to pass on and takes years to kill, while plague is found in many other animals, strikes with great speed, can be lethal within days and is highly contagious. Different as they are, each bears a wider lesson for students of disease; that our enemies – and our defences against them – have evolved, are evolving, and will continue to evolve, whatever medicine does to combat them.

The fifteenth-century Welsh poet Ieuan Gethin, in a diatribe against the fate of his seven children, wrote that ‘We see death coming into our midst like black smoke, a plague which cuts off the young, a rootless phantom which has no mercy or fair countenance . . . it is seething, terrible, wherever it may come, and a head that gives pain and causes a loud cry, a burden carried under the arms, a painful angry knob, a white lump. Great is its seething, like a burning cinder . . . It is a grievous ornament that breaks out in a rash . . . the early ornaments of black death.’ A century earlier Boccaccio, in the Decameron, a tale of a group of young people who flee from Florence to escape that city’s epidemic wrote that ‘The violence of this disease was such that the sick communicated it to the healthy who came near them, just as a fire catches anything dry or oily near it.’

Bubonic plague, the subject of the Welsh account, is marked by painful lumps or buboes, swollen glands that ooze blood and lymph. The pneumonic form of the disease attacks the lungs until the patient spits blood, while the septicaemic variety infects the blood itself. Each variant is painful, stressful, and in the end often fatal. Many of those afflicted died within a week, and some within a day. In some visitations, almost all those with blood-poisoning perished, and even with the milder bubonic version four out of five did not survive. Again and again, from ancient times onwards, corpses were piled high in cities and villages, so frightful was the carnage.

As Boccaccio noted, its agent is highly infectious. Unlike leprosy, plague enters the human population almost by accident, for it finds its permanent home within various rodents. The bacterium depends on rats and fleas or lice to spread to men and women. It is common among small mammals in central Asia, in a certain marmot most of all, and in the animals is transmitted by contact with infected corpses, or by fleas. Those insects bite other mammals, humans included. As the bugs teem in the fleas’ guts, their intestines become blocked and they regurgitate millions of bacteria into the next creature they sample. As a result, many epidemics began in ports such as Bristol, London, or Constantinople, where flearidden rats ran ashore from ships.

Pneumonic plague can be picked up from no more than a cough, which means that patients must be kept in isolation (as must their pets, for cats have passed it on to their owners). People can also be infected when they handle contaminated animals or meat (camel meat in central Asia, or guinea pigs in Peru or Ecuador). The illness can spread at great speed, for birds that nest in rodent burrows, or have mice in their own nests, may carry fleas and their passengers for miles. The bacillus can in addition survive in a dormant state in the soil.

The evidence for its presence in ancient Israel is equivocal. The First Book of Samuel speaks of when, at a crucial moment in the endless wars of those years, the Philistines seized the Ark of the Covenant and held it hostage. Soon they faced a great epidemic, for the Lord smote their men with ‘emerods in their secret parts.’ In addition he gifted them with an outbreak of mice.

Alarmed by this double blow the Philistines agreed to restore the Ark to the Israelites, together with reparations of five golden emerods and five golden mice. Perhaps the condition was indeed bubonic plague, the emerods its bloody swellings and the mice in fact rats that passed on the disease. Others suggest that it was instead dysentery, which can produce piles (haemorrhoids, or ‘emerods’ in the language of King James) and that the mice were just mice, with rats then unknown in the Middle East. Yet others have come up with the idea that the infection was tularaemia, a mouse-borne illness whose symptoms look rather like those of the plague and which could have been brought to the Philistines by mice that nested in the Ark itself. On that object’s return to its rightful owners, and as further proof of the power of the Lord (who was outraged that the Israelites had dared to look inside the holy relic) fifty thousand Jewish men died of the same disease, in support of the notion that a creature – perhaps an infected mouse – within the sacred casket was indeed involved.

Whatever the true fate of the Philistines, since their day plague has ravaged the world. Like leprosy it attracts the attention of the pious, who often blame malign intervention, sometimes by Jews (in the fourteenth century, after a visitation of the Black Death, all the Jews of Mainz and Cologne were killed, to no apparent effect). That epidemic reduced the world’s population by a quarter.

Its agent’s limited genetic diversity makes it possible to search out its roots. The bacillus was born in East Africa, spread from there to the Bible Lands and then moved on to the rest of the Old World. There were two invasions of Asia, the first through India and on to the Philippines, and a separate northern route from the Middle East through Turkey and Iran to China and Japan. Many later attacks in the Levant and in Europe involved a return journey from the Far East, borne by travellers along the Silk Road.

The Plague of Justinian struck the Byzantine Empire in AD 541. It killed half the people of Constantinople and reached across Europe. The next great incursion came in the fourteenth century, again from the Far East. Its passage was helped by the unhygienic habits of a Mongol horde who improved their siege of a Crimean city with a catapult that fired the corpses of those who had died of the disease into the streets (a trick updated in the 1930s by the Japanese, who dropped infected fleas onto Chinese towns). Terrified, the Genoese defenders fled homewards, taking their parasites with them. Around the Mediterranean the epidemic put paid to three in four of the populace. In northern countries its effects were less dire but the illness still led to the death of one in five. A quarter of all German villages disappeared and the economy of the whole continent went into reverse.

The plague came to London in 1348. The then Mayor, Richard de Kislingbury, ordered that two pits be dug, at East and West Smithfield. Within two years, more than a third of the city’s residents had succumbed. Thousands were buried in the new cemeteries. The sickness came back again and again, with its last great incursion into these islands in 1665 and 1666, when much of the population of the capital fled. The sole public health measure was a demand that all cats and dogs be destroyed (which was unfortunate as they might have killed the rats that helped spread the disease). The infection continued to flicker in and out of life in Europe and the Ottoman Empire until the mid-nineteenth century. A little later the last global episode – the so-called ‘third pandemic’ – flared up in China, spread as people escaped from a Muslim rebellion, and crossed the globe. It killed ten million in India alone and lasted until 1959, but by then casualties had dropped to just a couple of hundred a year. The threat was not over, for in 1994 there was a new Indian outbreak. There were no more than seven hundred cases and just fifty-six deaths, but many of the people of the affected region fled in panic. The condition is today classified as a ‘newly emergent disease’, for it lurks in its homeland, the world of the rodents, and now and again sallies forth to find a few more victims.

The agents of plague and leprosy, like those of malaria, of AIDS and of many other conditions, are in constant competition with their hosts. Disease is a microcosm of the machinery of evolution, for natural selection acts on humans to improve resistance, and the parasite must keep up, or disappear. For all infections, the Darwinian race is on.

Leprosy and its host have almost reached a dead heat. Several variants protect against infection while others control how fast the symptoms progress. The Prata leper colony in Brazil, on the edge of the Amazon forest, was founded in the 1920s by Dominican monks and for years was almost cut off from the rest of the country. More than two hundred of its two thousand inhabitants have Hansen’s disease – the highest incidence in the world – and almost all descend from earlier generations who faced the same problem. The chances of infection are much influenced by what version of a particular gene, its function unknown, anyone inherits. About one unlucky male in twenty bears two copies of a variant that renders them susceptible and almost all have symptoms by the age of thirty. Those with two copies of the alternative form are more or less safe. A scan of the whole genome in other patients reveals half a dozen other genes that differ in structure between those with a severe, and those with a mild, response to the bacterium. Some match elements of the parasite’s cell membrane while others are involved in the immune system.

Plague, too, has forced its victims to change but there the duel between the parties is still in full fury. A variant of a certain receptor molecule on the surface of white blood cells is common in places once ravaged by the Black Death. In the fifteenth century, some Adriatic islands were visited by an incursion that killed seven in ten and they, too, have a higher incidence of that form of the gene than do uninfected islands nearby, which suggests that it gave some protection.

Other mammals, too, evolve when faced with the bacillus. Yersinia was introduced into the United States in about 1900 and laboratory stocks of prairie dogs whose ancestors were trapped in Colorado and Texas, where the disease has become common, are much more able to survive infection than are their fellows in South Dakota, where it is unknown. Genes for resistance must be involved. The same is true of black rats in Madagascar. Analogous variants might be present in humans.

Plague and leprosy are at different points in a biological spectrum. Each has made a passage from animals to humans, each was obliged to change as it did so and each is still changing. The new comparative anatomy – the dissection of the double helix – shows how they did it.

Leprosy DNA has been read from end to end. It codes for just three thousand genes, of which no more than half make a protein. The remainder are mere relics of what they once were. The bacillus has lost a quarter of the genes found in its close relative, the agent of tuberculosis.

Plague has also simplified itself, but to a lesser extent, for in the world of the rodents it must switch from host to host to stay in business and cannot concentrate on a single narrow target. It is related to a bacterium transmitted on contaminated foods that does no more than cause stomach upsets. Since it set out on its own the agent of Black Death has changed in many ways. It has lost a substantial proportion of its genes but has gained others that enable it to survive within a flea, to spread through human blood, to extract iron from red blood cells for food, and to avoid its host’s immune defences. More remarkable, Yersinia pestis has picked up some of the variants that allow it to attack men and women not by mutation but by theft. The genes sit on pieces of mobile DNA called plasmids that have moved in from other bacteria. They are a menace, not just because they donate virulence to a once benign organism, but because some allow their bearers to break down drugs. They can even be passed from harmless bugs to the real killers. In 1995 the first multi-drug plasmid of this kind emerged in a strain of plague in Madagascar. It gave simultaneous resistance to eight antibiotics. The invader resembles another often found in bacteria from the guts of cattle, pigs and turkeys but it has not yet picked up the relevant section of DNA. If the resistant forms spread, plague – now more or less under control – may again become a global threat.

The plague bacillus was for many years divided by the experts into three varieties, the ‘antique’, the ‘medieval’ and the ‘oriental’, each defined by its needs when cultured in the laboratory. They were thought to have given rise in turn to the first, the second, and the third great plagues. The virulence plasmid has, the DNA shows, been incorporated only into the recent, oriental, strain. It is also present in specimens from the nineteenth century and from skeletons from a plague pit in Marseilles filled with remains from an epidemic in 1722. Some of the victims of London’s 1348 disaster have now been disinterred, and in a technical tour de force the genome of their killer read from end. A comparison of its structure with that of material from three centuries later and of several modern strains hints that both the fourteenth-century event and the Roman Plague of Justinian also involved that variant. If the bacterium has accumulated new mutations at the same rate as it did between the thirteenth century and the present day, its entry into the human race can be dated at around two and a half thousand years ago, which is just when the Philistines had such trouble with their emerods.

Plague still kills, but if caught early can be cured with antibiotics such as streptomycin. Molecular tests diagnose it in hours rather than the days once needed and allow treatment to start at once. Rat control has also helped. Even so, the illness will never be wiped out, because it finds a home among millions of wild rodents, often in remote places. The pandemics may have gone, but five thousand cases, with more than a hundred deaths, still turn up each year. Most are in Africa.

For leprosy, the future is more hopeful. Some day – like smallpox before it – the biblical scourge may be gone forever. For years, ignorance prevailed. The practice of laying on of hands lasted for millennia and both Elizabeth I and Charlemagne touched the afflicted in the hope that this would act as a cure. Another fad was to bathe in blood, that of a virgin best of all. If even that did not work, castration might be tried. Such treatments were succeeded by a variety of herbal remedies of equal efficacy.

A quarter of a million new cases are still diagnosed each year, but the infection is in retreat. It remains endemic in parts of the tropics but in Europe declined from the fourteenth century onwards, perhaps because of the spread of tuberculosis in crowded cities and the cross-immunity that bacillus gives against its relative. By the eighteenth century the illness had more or less disappeared from England, but survived for a further century in Scotland and until the 1950s in Scandinavia. In the 1930s came dapsone. The drug emerged from research by German chemists on certain dyes. They were, almost by accident, found to kill bacteria. That discovery led to the sulphur drugs, the first successful treatment for blood infections and for a range of other diseases. Dapsone interferes with the bacterium’s ability to make DNA and, as a result, reduces inflammation. The drug is not very powerful and for advanced cases must be continued for a lifetime. It can work, but many patients gave up before their medicine had time to do its job. Such rejection was a problem in India. Gandhi himself welcomed a leper, an ‘incurable’, into his home, an event celebrated on a postage stamp with the message that ‘Leprosy is Curable’.

Thirty years ago dapsone was shovelled out in quantity. The bacillus evolved to meet the challenge, resistance emerged, and the drug lost its power.

In 1981 came a breakthrough. A cocktail of three chemicals (dapsone included) was found to be far more effective against Hansen’s disease. The ingredients are now supplied free to the World Health Organisation by the drug giant Novartis. They work fast – so much so that, as treatment goes on, the death of billions of bacteria leads to the formation of painful nodules full of dead cells. Some patients abandoned the pills as a result. Then, quite out of the blue, thalidomide – once responsible for birth defects in the children of pregnant women who were given it as a sedative – was found to have almost magical powers to solve the problem. It acts against inflammation, and patients who are in torment with a rash of weeping pustules may show signs of improvement within a day.

Three decades ago, the World Health Organisation set the end of the last millennium as a target to reduce the global incidence of leprosy to a single case in every ten thousand people. It succeeded. Now the aim is to drive the disease down to that frequency within each individual country. That goal is harder to reach but is worth the effort, for success would mean that the agent might then die out of its own accord. In 2010, the WHO recorded a drop by more than half in the number of new cases compared to the figure a decade earlier. Leprosy’s capital is now in south-east Asia, but there its agent is in rapid retreat. The Americas are more recalcitrant, with little improvement in the past few years, but global incidence is on its way down, except in failed states such as Sudan and Yemen. Hansen’s disease will be around for a while, but a vaccine is under development together with plans for low doses of preventative drugs to be distributed to whole populations at risk. One day the ‘unclean’ may be no more than a memory.

As plague and leprosy are pushed back the question remains; where did they come from? They are not divine scourges but they do have a history that dates to biblical times and before.

Once again, DNA is the key. It shows, first of all, that each emerged from a lucky (or unlucky) accident. Darwin noticed that the remote islands of the Galapagos had fewer species of plants and animals than did the distant shore of South America because, by chance, just a few species, and a few individuals of each, made it across the oceans. Island creatures – humans included – are in addition less variable than their mainland relatives. Such bottlenecks have had a dramatic effect on the agents of disease. Many among them entered humankind just once, or on a few occasions. Like birds blown to a remote archipelago, or the first Americans as they pushed into a new continent, most of the travellers fail, but now and again one succeeds in its new home and its descendants explode in number. The genes show that both leprosy and plague arrived as single invaders, each a pioneer of trillions of cells. Their descendants exist in untold multitudes but vary, as a result, scarcely at all.

The leprosy bacillus is, apart from a few minor shifts that have emerged by mutation since it entered its present host, a single clone across the world. Strains from India, from Thailand and from the United States, together with the ancient relics found on the shroud at the Field of Blood, are 99.995 per cent identical. Plague tells the same story. Its agent is almost the same from place to place; a clone, or a few clones, that spread at great speed and picked up the occasional mutation and gene transfer on the way. The strains found among wild rodents are quite a variable bunch, but just a few have made the transit into Homo sapiens. The agents of anthrax, of smallpox, of pneumonia, of a certain form of diarrhoea are also of this kind. Syphilis, too, is almost a single clone, and emerged as an inadvertent retaliation to their exploiters by Native Americans, who passed the disease to the Spanish invaders, who took it to Europe in 1495. Its genes show it to be a close relative of a strain of the skin infection yaws that is found only in the New World. A virulent version of a drug-resistant bacterium that causes severe blood-poisoning – methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or MRSA – spread across Europe from Germany in the 1990s. It can kill in weeks. It too is uniform, and its founder cell must have mutated towards virulence within the past couple of decades. Typhoid, in contrast, consists of at least eight distinct lineages, each of which invaded Homo sapiens of its own volition. Even so, for many of our enemies the entrance ticket into the human race was won by a fluke.

Where did such creatures live before they found their new home? The Levitical obsession with the cleanliness or otherwise of animals has a basis in fact (even if many of those it names as ‘clean’ have been a source of infection). Men and women are but islands in an archipelago of illness. Almost all agents of disease have relatives among animals, wild or domestic. Often, the entry into humans coincided with a change in our relationship with such creatures, as farmers began to till the soil, as the first cities emerged, and as people today move into once virgin landscapes and fly in vast numbers across the globe.

Around fifteen hundred different organisms are known to invade the human body. Two out of every three come straight from a wild animal. Few go any further, which means that from their point of view men and women are dead ends (even if they kill their hosts before they themselves expire). The raccoon worm, for example, is more or less harmless to its usual target but should a child eat its eggs (found in faeces) the invader may get to the nervous system and can be lethal. The infection is bad news for both parties.

Other parasites have had more success. They have adapted to their new habitat and, as always in evolution, have made compromises to do so. Leprosy and plague are a microcosm of the expedient and ingenious struggle between ourselves and our biological foes. The battle may end in the death of either parasite or host, or in a disease that allows its victim to survive before its agent moves on. In other cases there emerges an uneasy truce in which both players persist (albeit at some cost to health) and in time such a relationship may even become an alliance from which each signatory gains.

Any intruder must balance virulence – damage – against infectivity, the ability to find a new target. The outcome may depend on how easy it is to find the next victim. A safe refuge in the outside world, a reservoir from which the pool of potential hosts can be topped up, allows an invader to pay less attention to the upkeep of its human home, for should that individual perish before the bacillus can infect somebody else, plenty of its relatives are waiting behind the scenes. The reserve may be within wild creatures, or may consist of resistant spores or particles (such as those found in anthrax or tuberculosis) which can survive in the open for months. All this abets aggression, for such parasites face less pressure to keep their hosts alive than do those, like leprosy, that must move directly from person to person.

The agent of typhoid fever travels from one person to the next in unclean food or polluted water and can sometimes kill, but many of those who pick it up remain healthy but infective, sometimes for a lifetime. ‘Typhoid Mary’, who worked as a cook in New York in the 1900s even when she was forbidden by the courts to do so, passed on the bacterium to fifty people, three of whom died, before she was confined in a hospital on an island in the East River. Cholera is another water-borne disease with much the same symptoms but is much more lethal. Unlike the agent of typhoid it finds a safe long-term haven in the egg masses of mosquitoes and in tiny freshwater relatives of crabs. It can hence afford to kill off its human hosts without breaking the chain of transmission and often does so. Like plague, cholera owes much of its aggressive behaviour to an incorporated piece of DNA, and is quick to adapt to changes in conditions. In Angola – which had reported no cases since 1998 – a new and lethal variant emerged in 2006. It bore a new alien helper and soon spread through the slums that emerged after civil war forced people to flee to the cities.

The equation between virulence and infectivity is not absolute for some dangerous diseases such as tetanus (caused by a soil bacterium) are not highly contagious while others such as rabies kill off both dogs and humans at great speed, even without a third party to act as a refuge. Even so, each step in the journey from harmless outsider to mortal enemy can still be seen in the world of the parasites. Plenty of animals have diseases of their own that do not bother us. Bird malaria does not attack people and nor does the viral distemper that can kill dogs. Other agents, like the raccoon worm, in effect commit suicide should they enter a human host. Yet others, like plague, do kill, but need a second or even a third host to allow them to persist. For them, no helper means no hope. The West Nile virus illustrates the problem. It causes high fever and is passed on by mosquitoes. It originated in Africa, spread to Europe, and appeared in the United States in about 1999. It may have been carried by a migrant bird, by a feverish human or by an insect stowaway on a long flight. It took just four years to cross the country and did so with the help of introduced Old World mosquitoes. Europe faces a similar problem, for the tiger mosquito, a recent invader from Asia, can bear the agent of dengue and is on the move across Italy, Greece and France. Just one bite of a diseased traveller home from the tropics may be enough to start an epidemic.

Other pathogens move from one victim to the next often enough to spark off a brief wave of infection, but to persist need a regular top-up from an animal host. The many variants of Influenza A (most of which come from pig and duck farms in China) are of this kind. They cause a major outbreak every few years, but die out as their targets expire or become immune. Not until a new variety to which most people are susceptible escapes from its swinish refuge can a new epidemic take hold. The Ebola virus, an African disease that causes patients to vomit blood and can kill in days has taken the next step in the journey by starting to cut out the middle-man. The illness was first noticed in 1976 when it attacked people who had been in contact with infected chimpanzees (and twenty butchers died when they cut up a tasty specimen). Antibodies show that it is not a new disease, for as many as one person in five in some places has been exposed to it over the decades. It can be lethal to gorillas and chimpanzees and an infection from those sources can still kill us, but the virus can now also pass directly from patient to patient in hospitals.

Other afflictions have taken the final step and maintain themselves as exclusive residents in a human host. Smallpox, syphilis, measles, leprosy, the human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis are all of this kind. Every infected person must pass on the relevant agent to at least one other individual if the disease is to maintain itself.

Sallies across the species barrier that spark off new infections tend to happen at times of upheaval. Skeletons from before agriculture show that plenty of people had malaria, gut microbial infections and a variety of parasitic worms, although they were free from smallpox and the common cold, which need large populations to survive. These diseases led many to premature death or to a life of misery. With the first farms, men and women began to form new relationships with creatures as different as mice and elephants (the latter among the few domesticated creatures not known to have passed on any agent of infection). At once, the empire of illness extended its borders. Because more animals were tamed in the Old World than in the New, most of its citizens originate there rather than in the Americas.

Measles is related to the cattle disease rinderpest, itself declared extinct not long ago. It found a home in humans with the first herds, seven thousand years before the present and, in spite of vaccination, remains a menace. Tuberculosis, too, is an ancient scourge that resembles a cattle infection. Smallpox arrived three thousand years later – within biblical times – perhaps with a virus that leapt from camels to their riders.

In spite of such attacks, human numbers continued to grow. Soon, the swarms of people imposed a new ecology upon mankind as the first towns and cities (Babylon included) appeared. At once, they became hotbeds of contagion, although New World conurbations such as Tenochtitlan, later to become Mexico City, reached a similar size with no epidemics as they had few domestic animals. A dozen or so of today’s diseases must have arisen after such places emerged, for they pass from person to person and would never survive in a scattered rural population. The killers found further opportunities as contacts increased. Enemies travelled faster than did civilisations. A great pestilence in Athens at the time of the Peloponnesian War in 430 BC was described by Thucydides as an invader from Libya via Egypt. It devastated the city (‘the bodies of dying men lay one upon another and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water’). The culprit may have been typhus, passed on by lice and still the companion to war, from the trenches of the Somme to refugee camps in Rwanda.

Imperial China’s health records stretch from 243 BC, the time of the First Emperor, to 1911 when the Manchu dynasty collapsed. They tell of almost five hundred outbreaks of illness. For its first three centuries, the empire saw almost no epidemics. From the time of Christ to that of William the Conqueror the numbers of citizens and of outbreaks each increased but most of the populace was spared for decades at a time. In the twelfth century, as numbers grew further and as thousands moved into towns, attacks took place once every couple of years. Most did not spread far. As the population grew yet larger and as people began to move between cities epidemics happened every year. Soon, they covered vast tracts of the empire. Some, such as the incursion of plague in the thirteenth century, killed half the Emperor’s subjects.

European explorers much extended the invaders’ reach. The people of the New World, of the Pacific and of Australia – until then spared – were devastated by plague, leprosy, tuberculosis, smallpox, malaria and measles. The entry of Captain Cook into Polynesia came at huge cost, for the natives were exposed to enemies against which they had no defence. His diary records the ravages of venereal disease (brought, he assumed, by the French): ‘They distinguished it by a name of the same import with rottenness, but of a more extensive signification, and described, in the most pathetic terms, the sufferings of the first victims to its rage, and told us that it caused the hair and the nails to fall off, and the flesh to rot from the bones: that it spread a universal terror and consternation among them, so that the sick were abandoned by their nearest relations, lest the calamity should spread by contagion, and left to perish alone.’ Not until the 1960s did the Pacific regain the numbers who had lived upon its islands before the Discovery arrived.

The age of infection that began with the first farmers lasted for ten millennia. For most of that time, global life expectancy was no more than twenty-five and most deaths were due to contagions of various kinds. In the developing world they still kill half of those who perish before the age of forty. The parasites that made the leap from animals to ourselves have had a long and comfortable career.

Five decades ago, their reign seemed to be almost at an end. Medicine would soon lay its metaphorical hands on the sick and cure them all. In the 1960s confident claims were made, in books with titles such as The Evolution and Eradication of Infectious Disease that ‘It seems reasonable to anticipate that within some measurable time, such as 100 years, all the major infections will have disappeared.’ In those happy days few remembered the visitations of plague, syphilis, cholera and Spanish flu, each of which had killed millions not long before. Then came AIDS, pessimism and panic. Older enemies have also reminded us of their power. Tuberculosis, once almost gone from developed countries, has returned and now infects more people than ever before. There have been outbreaks of cholera and of swine-flu as further reminders of what may lie in wait. Even trench-fever, a louse-borne illness associated with the horrors of the First World War, has made a comeback among the homeless in the United States.

The price of health is eternal vigilance. Without it, our enemies may again find themselves in the same happy position as Captain Cook when he stepped ashore in Australia, in a rich new continent ready to be exploited. Society is in the midst of a transition as great as that at the foundation of Babylon. Mankind is on the move as never before, across oceans and borders and into jungles, forests and deserts, in a search for food, for minerals, or for suburban comfort. As people move they expose themselves to the dangers that destroyed the empires of long ago.

At least thirty illnesses have emerged from contact between humans and animals in the recent past. They include the human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, bovine spongiform encephalopathy or BSE (which manifests itself in humans as the brain disorder Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) and several bloody fevers of viral origin.

Apes and monkeys have donated AIDS, hepatitis B, the most severe form of malaria, dengue and yellow fever. HIV made the leap from a chimpanzee to a West African hunter not much more than a century ago, but now thirty million people carry it. It is a disease not just of humans but of chimpanzees themselves, for infected animals die young. Our close relatives have plenty more on offer. Africans who hunt or butcher wild apes and monkeys, or those who keep them as pets, are most at risk. In Cameroon – where HIV first moved from chimps to humans – monkeys and apes carry infections from another group, the simian lymphotropic viruses, which enter white blood cells. Many hunters bear them, as do members of their families, for, like HIV, the particles are transmitted during sex. The virus causes muscle damage. A related pathogen, the chimpanzee simian foamy virus, is also common among the citizens of Cameroon, but in spite of its close resemblance to the agent of AIDS it seems to do no harm.

Pigs, too, are threatening creatures. Not only are they the source of swine-flu, they can also carry the Ebola virus, which may one day leap from that widespread reservoir to ourselves. Twenty years ago in Malaysia piggeries were set up close to fragments of tropical forest. There, in 1998, the Nipah virus crossed from fruit-bats to pigs and thence to those who farmed them. It killed a hundred people. A million animals were slaughtered. That did not hold back Nipah, which moved as far as Bangladesh. Once transmitted from bat to pig, and from pig to man, Nipah has now gained the ability to pass from person to person with no help from a third party.

Bats bear many other lethal viruses, rabies and Ebola included. Every fifth species of mammal is a bat, and the destruction of forests has encouraged the animals to move closer to towns and cities. The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome or SARS that began in China in 2003 and crossed the world was first blamed on civet cats sold for food. It was contained with quarantine and with the slaughter of thousands of wild civets but now it appears that, once again, bats are to blame. Fruit-bats have been known to fly three thousand kilometres. They might as a result carry once rare illnesses to great cities such as Sydney, which is, perhaps mistakenly, proud of the colony in its Botanic Garden.

Other parasites have leapt into action as people themselves feel the call of the wild. Lyme disease, which leads to a painful inflammation, is caused by a relative of the agent of syphilis. As suburban homes sprang up in the northern woodlands of the United States, the locals came into contact with deer and mice and their infected ticks, and suffered as a result.

Not all the news is bad. For leprosy, plague, polio and more there has been real progress. Many other illnesses – malaria, dengue, and cholera included – could also be mastered if the political will was there. Smallpox has disappeared, polio may be on the way out (even if there has been a resurgence since some Islamic authorities declared vaccination to be a plot to sterilise Muslims) and the last days of leprosy may not be far away. The parasitic worms of Africa have been driven back at speed and optimists claim that many of the other epidemics that began with agriculture may be defeated in the next few decades.

Another reason to be cheerful is that some (but not all) dangerous illnesses appear to moderate their effects as the years, and the centuries, go by. Smallpox became less virulent in the years before its elimination, while the ‘great pox’ (otherwise known as Morbus Gallicus, the French disease, even if the French blamed it, correctly, on Native Americans) that swept across Europe in the Middle Ages and killed in a few months, has slowed its progress in its modern form, syphilis. Cholera, too, is in most places less lethal than once it was. The viral illness dengue, or break-bone fever, in contrast, has travelled in the opposite direction. Until the 1950s, almost all those affected had just a single infection, which was painful and unpleasant, but primed their immune system against later attacks. Now, other variants have spread with the global movement of population and a second infection with one of those may be lethal. The evolution of virulence, like that of everything else, does not follow simple rules and the claim that all diseases follow a programmed path to be kind to their hosts is not correct.

Even so, some of our erstwhile enemies have moved towards uneasy compromise. Other disease organisms have gone further. They have moved so close to an accommodation with those who bear them that, most of the time, they are not noticed. Like the benign skin fungi that attack AIDS patients only in the last stages of their illness, or the bacteria that do their damage when the body is weakened after surgery, they are a risk only to the susceptible, be they the aged, the frail, or those with a damaged immune system. In the same way, a certain skin bacterium causes no problems until hormonal changes at puberty allow it to invade glands and cause acne.

Some of our hangers-on have taken yet another step for they live with us not as enemies but as at least temporary friends.

Each reader of this book is less human than they were on the day when they were born. Every baby emerges pure into the world but, within minutes, is invaded by battalions of foreign cells that soon teem throughout its body. All adults have ten times as many bacteria in their guts as they have cells of their own (which means, in terms of cell count, that the equivalent of just one leg below the knee is truly human). Billions more are secreted around the nooks and crannies of the skin, the mouth and elsewhere. Each of us is laden down by more than a kilogram’s worth of these tiny outsiders. Together, they weigh as much as the brain and there may be ten thousand distinct kinds, each with its own set of inherited information, which means that our residents contain a far greater diversity of genes than do our native cells. Everyone’s mixture is as unique as a fingerprint (and the police have used that fact to see who has been at work on a particular computer). Its identity changes little from day to day or week to week although it does shift in old age. The forehead’s community is distinct from that of the arm; and the leg from the sole of the foot. Mouth, stomach and vagina each have fewer types than do other sites (and, for some reason, the back of the knee is more diverse than anywhere else). The mix also varies in identity across the world.

Such aliens were once seen as harmful, and a whole generation of cereals and laxatives promoted ‘inner cleanliness’ by expelling them. The habit goes back to the Egyptians who, three thousand years ago, saw faeces as a cause of disease and gave themselves enemas every few days. More recently, many doctors claimed that to get rid of the noxious hangers-on would avoid ‘auto-intoxication’ because of their presumed tendency to poison their carriers. Some people thought that they were responsible for age itself and told surgeons to cut out bits of intestine in the hope that they would live longer. The Nobel Prize-winning immunologist Élie Metchnikoff was convinced of the dangers of such ‘putrefactive microbes’ and dismissed the entire large intestine as a vestigial organ of no use. On his death-bed at the age of seventy-one, he asked the doctor who was to do his post-mortem to pay particular attention to the length of his gut in the hope that there might lie the key to his success in reaching three score and ten.

The notion that the inner self is unclean is quite wrong. Instead its denizens are a forgotten organ, as essential as the kidney or the liver. We depend as much on our internal citizens as they do upon us. In the large intestine, they break down indigestible plant tissues to feed themselves, but as a by-product they make chemicals that can be soaked up by our own guts. In addition they neutralise poisons and get in the way of pathogens that might otherwise settle in. Their biological signals help gut muscles and nerves to develop, which means that children who possess a certain combination of gut residents are at higher risk of obesity and of diabetes than are those with a different mix.

Should the internal ecosystem be disturbed by an attack of aggressive bacteria, the appendix – once assumed to have no useful role – acts as a reservoir from which the useful cells can emerge when the threat is over. Sometimes, the gut flora is wiped out by antibiotics. Other, more noxious, bacteria may then take over and can kill. A simple, startling and often effective treatment is to carry out a faecal transplant; to insert the intestinal contents of a healthy person into the patient in the hope that this will restore the internal balance. The commercial yoghurts that claim to do the same job are, however, useless.

A long history of cooperation has led to an interaction with our inner army so intimate that its absence, rather than its presence, leads to illness. Laboratory mice raised in germ-free conditions do not thrive. Their immune systems do not work well, their intestines fail to move as they should, and they tend to be unhealthy. Such animals are also anxious and obsessive and have a poor memory. The inhabitants of the intestine may once again be involved. They make plenty of the nerve transmitters associated with mood and anxiety. They also generate nitric oxide, which helps to pass information between nerves and is important in emotion. Their unexpected ability to keep us cheerful adds fresh significance to the biblical ‘bowels of compassion’.

One of the most important tasks of the colonists is to prime the immune system. The developed world is in the midst of an attack of allergies, of childhood asthma, of skin eruptions and of other conditions in which the body’s defences fail to respond as they should. Such conditions include multiple sclerosis, juvenile onset diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome, in all of which the protective protein attacks the body’s own tissues rather than the threats from outside.

Some of this may be due to today’s excessive cleanliness. Too much hygiene might be harmful because it destroys our internal ecosystem. Parts of the modern world have almost attained the purity hankered after by the Levites. The gut ecology of African children differs from that of Europeans and – although many other variables are no doubt involved – they do not have as many allergies. Middle-class British children from small families without a cat or dog, with homes in cities rather than in the mire of the country, and those who stay with their mothers rather than going to nursery, are safer from parasites and infection than are others and they too suffer more from such failures of the immune system. Turkish immigrants in Germany who often visit their native land have more gastric upsets than do their fellows who stay in Europe, but they also experience fewer immune problems. In the same way, mumps, chickenpox, measles and other childhood diseases are less common among children in poor tropical countries who are infected with hookworms than among their uninfected peers, as a hint that their parasites have improved the efficiency of the immune system. Inflammatory bowel disease – once rare but now common – first emerged as a real threat in rich people living in cold climates, where worms are rare; and the last American group to begin to suffer from it were poor African-Americans.

Twenty years ago, a certain bacillus was found to be the cause of most stomach ulcers. The response was to hit it with antibiotics. The treatment worked. The organism is, or was, found in almost every stomach on Earth. Such is the modern use of antibiotics, with most American children having a dozen rounds of the stuff before they are eighteen (and their British equivalents facing almost as many) that only one in twenty now bears the bug. That is unfortunate, for the same bacterium has the unexpected task of interacting with appetite hormones. Farmers found some years ago that antibiotics given to intensively reared chickens, pigs or cows makes them put on weight and lay down fat, for reasons then obscure. They do the job, we now know, because they kill off that stomach bug and, in turn, push up the appetite hormones and make the animals hungrier than they were. Good for profits as that might be, it hints that at least part of the wave of obesity that afflicts the developed world may be due to the loss of a once universal stomach bacterium. It is a friend to the young, but an enemy to the old.

For most of history, all infants have had such mild, and not so mild, hangers-on. Fifty million children are still treated for parasitic worms each year. Invasions of this kind involve a conversation between parasite and host as each adapts to the other until, in time, the immune system is sufficiently well educated to do its adult job. Certain viruses, such as that for hepatitis A (a food- and water-borne disease that has little effect on most people) are particularly effective. Antibodies against it were present in almost all British children fifty years ago but the proportion has now dropped to just one in four. The immune system is learning less than once it did.

So strong is the tie between cleanliness and inflammation that a little judicious dirt – or even a well-chosen parasite or two – may help to fend off some of the problems that come from immune failure. Patients with multiple sclerosis sometimes find that a dose of worms reduces the frequency at which the symptoms recur. A refreshing drink based on the live eggs of an intestinal worm of pigs is also effective in around half of all patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A revulsion against that idea has led to the search for the parasites’ own chemical signals of identity in the hope that they might prime the immune system instead. Clinical trials are under way.

To treat plagues with human waste (let alone with pig parasites) would no doubt have shocked the Israelites. Even so, now that the biblical ideal of purity, in body if not in mind, has in part been achieved, the result has been a wave of illness that may be countered by a partial return to the unclean world in which they and their fellows lived. Cleanliness is not as close to godliness as the Good Book makes out. The urge to reject those cursed by infection has been replaced by the idea that impurity has a part to play in keeping ourselves pure. How would Leviticus, the scourge of lepers, have coped with that?