THEME 4: DEVELOPMENTAL AND EDUCATIVE APPRAISAL FOR ONGOING LEARNING

Nurturing and Retaining Quality: Beginning Teacher Induction

The importance and seriousness of ITP in Singapore is signaled by the Teachers’ Pledge, first at the start of candidates’ program at a ceremony known as the Teachers’ Compass Ceremony (TCC) and then at the graduation ceremony known as the Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony. The Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony is attended by the minister of education, as well as faculty and administrators at NIE, including senior management, such as the director and deans, and is reported in the public media. The ceremony runs over the course of a week and represents an important initiation ritual for all new teachers to “strengthen their identity as to who teachers are and what they represent” (Lee & Low, 2014b, p. 57). In reciting this pledge as they enter the profession, novice teachers voice aloud their commitments and responsibilities as teachers:

We, the teachers of Singapore, pledge that:

- We will be true to our mission to bring out the best in our students.

- We will be exemplary in the discharge of our duties and responsibilities.

- We will guide our students to be good and useful citizens of Singapore.

- We will continue to learn and pass on the love of learning to our students.

- We will win the trust, support, and co-operation of parents and the community so as to enable us to achieve our mission. (MOE, n.d.a.)

The pledge has been articulated in the Ethos of the Teaching Profession (AST, n.d.b.) and underscores a national vision of teachers as valuable professionals. Teachers’ professional development is conceived as a continuous journey with ITP as only the first stage of this process. Therefore, it is acknowledged that “no preservice teacher preparation programs can fully prepare teachers with all the competencies of a professional teacher” within a finite period of time (Lee & Low, 2014b, p. 56). It is assumed that competencies can be further developed during the span of a teacher’s career through professional learning (Lee & Low, 2014b).

Upon graduating from their preservice programs, all beginning teachers (BTs) are provided—according to their content specialization and the needs of schools—with induction support that is centrally managed by MOE. Induction spans novice teachers’ first two years of teaching. Virtually all new teachers (99%) are immersed in formal induction programs, a level much higher than the average of the countries that participated in the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) (OECD, 2014b). A comprehensive teacher induction program known as the Beginning Teachers’ Induction Program (BTIP) is provided by AST to “establish even and high standards of professional expertise across the fraternity” (AST, n.d.a.). Funding for all BTIP programs comes from MOE, which has as a primary objective to help BTs experience success and to enhance their passion, conviction, and beliefs in/of teaching. This two-year induction program helps BTs transition from preservice to in-service professional learning and strives to provide BTs with:

- an understanding of their roles and responsibilities, as well as the professional expectations and ethos of the teaching service;

- the opportunity to take ownership of their professional growth and development;

- a sense of belonging to the teaching fraternity; and

- a support structure for their personal well-being (AST, n.d.a.)

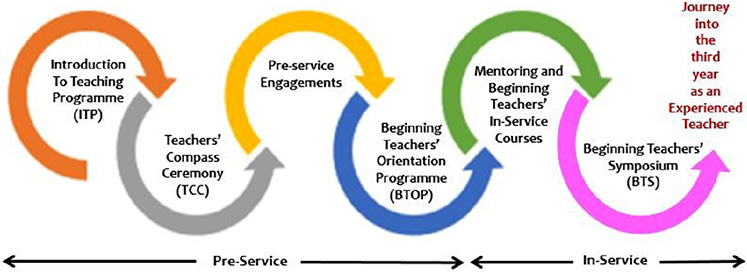

Figure 6 lays out the structure of the teacher induction framework. While it starts, in essence with the Teachers’ Compass Ceremony before the start of preservice preparation, it picks up post graduation with the Beginning Teachers’ Orientation Program (BTOP). Within the first two years, BTs attend in-service courses designed specifically for them, are exposed to school-based mentoring, and visit the MOE Heritage Centre. The two-year journey concludes with the Beginning Teachers’ Symposium. Once BTs enter into the third year of their professional life, they are considered to be experienced teachers. What follows is a brief description of the various stages and components in the framework.

Figure 6. MOE Teacher Induction Framework.

Source: AST, n.d.a

Beginning Teachers’ Orientation Program (BTOP)

Post graduation, BTs participate in a three-day BTOP, which allows them to consolidate their learning; understand their roles and the expectations of the profession; reflect on their personal beliefs, values, and practices within the context of the larger fraternity; and recognize the importance of nurturing the whole child (AST, n.d.a.). These expectations, roles, beliefs, and values are articulated in the Ethos of the Teaching Profession to guide the conduct of teachers and ensure that they meet the standards of the profession.

In-service Courses (for BTs)

Building on the foundations laid by NIE, the in-service courses serve to further enhance BTs’ professional competencies. The courses cover a wide range of topics, such as classroom management, parent engagement, teacher-student relationships, reflective practice, pedagogies, and assessment literacy. In addition, BTs are encouraged to complete an online course for newly appointed civil servants: Public Service Orientation Kit (AST, n.d.a.).

MOE Heritage Centre (HC) Visit

The MOE HC was recently constructed as a place to “showcase Singapore’s Education Story from the early 19th century to the present,” to affirm the work of currently serving educators, and to celebrate the contributions of pioneer educators and communities that have shaped the education system in Singapore (MOE HC, n.d.). The gallery exhibits highlight every phase of the nation’s development and the role education played (Heng, 2011). In addition, the center contains interactive and reflective galleries for visitors to reflect and reminisce on their past experiences as students (Heng, 2011). The aim of the MOE HC visit is to “deepen BTs’ understanding and appreciation of the role of education in nation building” (AST, n.d.a.). In addition, it aims to foster BTs’ “sense of pride and belonging to the teaching fraternity” (AST, n.d.a.).

Beginning Teachers’ (BT) Symposium

The symposium serves as a platform to promote teacher ownership and teacher leadership among BTs. Its stated theme is: “What Matters Most: Purpose, Passion, and Professionalism,” which calls for effective practices and strong commitment to the profession. This symposium happens at the end of BTs’ second year; thereafter they are no longer considered as BTs but experienced teachers.

Collectively, these BTIP programs help BTs to bridge the gap between their preservice and in-service learning. They serve as the initial level courses of professional development, which can be extended to higher levels during further professional learning.

Structured Mentoring Program (SMP)

Besides the induction program in place for BTs, the schools they enter typically have in place a systemic framework for school-based mentoring. Mentoring arrangements and programs are typically overseen by the school staff developer (SSD) and teacher leaders. One of the many school-based mentoring programs is known as the Structured Mentoring Program (SMP), launched on January 27, 2006. The aim of SMP is to level up the standard of induction and mentoring practices, which historically varied across schools, and enable BTs to gain knowledge within a community of practice with the support of a more experienced peer. In leveling up the standard of induction and mentoring practices, SMP has defined mentoring and induction as a schoolwide practice that benefits all teachers and encourages growth. Thus, as one interviewee stated, “Even the principal, vice principal, see me, they will check with me how I am getting on, give me advice” because the goal of mentoring support is ultimately, “if I teach you right, you’ll get better (as a teacher).”

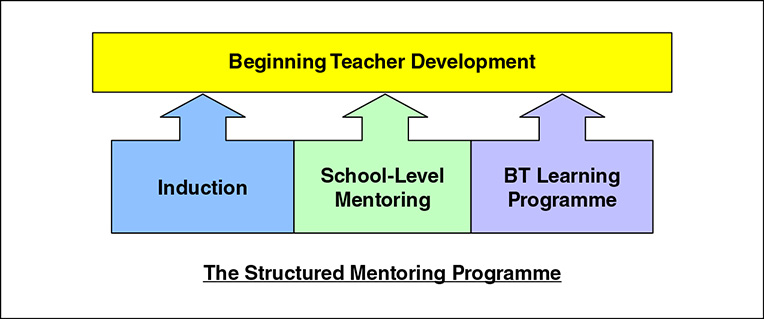

The SMP conceptual framework (Figure 7) consists of three main dimensions: induction, school-level mentoring, and the BT Learning Program.

Figure 7. Key Components of the Structured Mentoring Program for BTs.

Source: Chong & Tan, 2006, p. 5

School-level mentoring is seen as crucial to BTs. The guidance and coaching BTs receive from experienced mentors help them effectively transfer and translate their learning in preservice preparation into their classrooms and learn practical knowledge and skills in teaching (AST, n.d.a.). Regular conversations are held between teachers and their mentors, who are usually senior and lead teachers in schools.

There is therefore a need for mentors to understand the main goals of mentoring, which are induction to the school community; BTs’ professional development; and BTs’ growth in terms of helping them realize their personal and professional aspirations. TALIS results indicate that among all countries in the study, Singapore has the highest ratio of teachers serving as mentors (39%) or who currently have an assigned mentor (40%), in sharp contrast to the TALIS averages of 14% and 13%, respectively (OECD, 2014b). In addition, of particular importance is the fact that 85% of the mentees are assigned to mentors who teach the same subject, compared to the TALIS average of 68% (OECD, 2014b).

To ensure better training and clearer expectations of mentors, the MOE created a Skillful Teaching and Enhanced Mentoring (STEM) (Link 12) program in 2011. The aims of STEM include discovering good models and practices for the mentoring of BTs and ensuring more even mentoring practices, thereby leveling up the quality of teaching across schools. This initiative began with 30 prototype schools and included the training of in-service teachers. In 2016, there are now 120 STEM schools. Under STEM, the Mentor Preparation Programme (MPP) was developed with the New Teacher Centre (USA). It focused on the professional development (PD) of instructional mentors, which intensively prepared them with the mentoring language, tools, and processes to deepen their practice in supporting BTs’ learning.

Mentors serve in different capacities. There is usually a mentor coordinator who leads and drives the school’s mentoring program and acts as the “mentor for mentors” so that the mentoring goals at the school level can be achieved (Janas, 1996). Then there is the mentor, usually a more experienced teacher or teacher leader (e.g., senior teacher, lead teacher) who serves as a pillar of professional support for BTs as they continue to hone their professional competencies. The mentors would typically have received PD to prepare them for this mentoring role as it is a central part of their job.

Mentoring is a compulsory part of being a teacher leader (i.e., senior, lead, and master teachers). Teacher leaders are typically given primary responsibility for supporting and mentoring new teachers, support that runs the gamut from technical assistance, subject-specific pedagogical leadership and modeling, to socioemotional support: PD; resource sharing, etc. They have time especially set aside, professional learning provided, and expectations formalized for mentoring novices. New teachers we interviewed expressed their appreciation of “all the mentors I had, all the teachers I worked with” because they were “all very supportive, quite caring. They will check constantly how are you coping, any help they need to offer.” We heard that “Mentors try to use [mentee’s] prior knowledge. . .[to]. . . try and build on [mentee’s] strengths” and help new teachers come to “know about school culture, what are the expectations, some of the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts.’” In interviews, respondents felt that help was constantly available to them, “I don’t even need to ask ‘Can I borrow?’ [Mentors] will say, ‘Come and take.’ So I think it’s a very good environment. . . everyone is helpful.”

We also learned that mentors support their mentees in going beyond the immediacy of daily practice, by encouraging them to build their knowledge. Mentors “will ask you things like, ‘Have you heard of this concept called, say, tacit learning? No, right? It’s quite new you know. Maybe you should know about it. I don’t really agree with it. Let me know what you think. ’” Or maybe one might “sit down next to you and say, ‘I’m reading this book. It’s really interesting. Why don’t you read a few pages and tell me what you think about it?’”

Ms. Tan Hwee Pin, principal of Kranji Secondary School, described the support for beginning teachers in this way:

We welcome our BTs to our school as part of our Kranji family. It is important to induct them into our school’s culture so that they know the role that they play and the expectations and standards required when they interact with our students. Our mentoring programme is led by a team of seven senior teachers, under the advice of our vice-principal. Every BT or trainee will be given an experienced teacher as their mentor. BTs not only observe lessons of their subject areas, but also teachers from other subjects; I believe that every subject teacher has different strengths and they employ different pedagogies in different disciplines. By casting the net wider, new teachers will be able to assemble a repertoire of strategies, which they can activate when they become a full-fledged teacher.

Senior teacher, Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin elaborates:

BTs are attached to a particular senior teacher. On the first day of school, the senior teachers welcome BTs in the morning, introduce them to the school, and go through the induction program with them. The program will include topics such as timetabling, how to take leave, how to carry themselves as a professional in school, and also make sure they have a proper workstation. They also bring BTs to meet with the senior management for an introduction and chat, just to make sure that they feel welcomed in the school.

Besides the help that BTs get from senior teachers, schools also have a buddy system. The buddy is usually someone who is teaching the same subject as the BT, since the senior teacher may or may not be teaching the same subject. The mentor’s responsibility is more of grooming the new teacher in terms of the pedagogical dimension, while the buddy usually serves as a more immediate contact when the BT needs help in administrative matters, a source of information on the department or school, as well as a friendly face and a listener. Talking about how the mentoring program helped him professionally when he was a new teacher, Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor (RGS), shared:

To me what really helps as a new teacher is the mentoring and a buddy system. That is the most important. Knowing that you can actually approach somebody at any time of the day, and that person is very open to listening to you, it helps a lot.

BTs are typically given about 80% of the teaching workload of an experienced teacher, during which they are also subject to confirmation. The reduced workload is to provide the additional time and space for BTs to grow into their profession. In Singapore, the probationary period for BTs is one year. Once teachers are confirmed, they do not need to be recertified or licensed. Thus, confirmation has been taken to be analogous to having tenure. Sclafani and Lim (2008) observe:

New teachers are observed and coached by grade-level chairs, subject area chairs, and heads of departments. If a teacher is not performing well, additional support and coaching come into play. Everyone tries to help the new teacher adjust and improve, but lack of improvement, poor attitude or lack of professionalism is not tolerated. . .[T]he new teacher may be allowed to try another school, but if a year of working with the teacher has not improved his or her performance, the teacher may be asked to leave the profession. The system believes that it should do its best up front and counsel out those who do not make progress despite the support and assistance. Past this milestone, very few teachers are asked to leave, and then the causes may be lack of integrity, inappropriate behavior with a student, financial mismanagement, or racial insensitivity. (p. 4)

Note that the one-year probation period should not be confused with the two-year induction for all BTs. In other words, the confirmation after probation is not tied to the completion of the two-year induction period.

Professional Learning and Recognition

Retaining quality within the profession is not just about ensuring that BTs are carefully inducted into the profession, but also about ensuring that attrition rates remain low even after teachers have spent many years in the profession. In order to ensure that talent is retained within the profession, the ministry announced the GROW package in 2006, which was designed for the professional and personal Growth of education officers, through better Recognition, Opportunities, and seeing to their Well-being (MOE, 2007). The package created more opportunities for teachers to develop and strengthen their core competencies, provided more career options and choices, and gave greater recognition to the everyday work of teachers.

Since then, there has been an updated GROW 2.0 package, and the summary of the enhancements are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Summary of GROW 2.0 Initiatives

Well-being

|

Growth

|

Opportunities

|

Recognition

|

Source: MOE, 2007.

The main initiatives in GROW 2.0 are described in detail in the May 2008 issue of MOE’s Contact: The Teachers’ Digest (http://www.moe.gov.sg/corporate/contactprint/pdf/contact_may08.pdf) and MOE’s press release entitled “Putting People at the Centre of the Education Enterprise” on 28 December, 2007 (http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2007/pr20071228.htm), but will be briefly summarized here according to the order of growth, opportunities, recognition, and well-being. The first is growth. In line with MOE’s emphasis on lifelong learning and continuing education, GROW 2.0 provides a range of PD packages to help graduate and nongraduate teachers improve themselves academically. There is greater support for postgraduate studies in terms of offering full-pay study leave for teachers who want to pursue master’s/doctoral studies and more teacher posts for schools that have teachers pursuing full-time postgraduate studies. Nongraduate teachers can attend part-time on-campus degrees offered by local universities, including NIE and Singapore Institute of Management University. In 2014, Mr. Heng Swee Keat, the Minister for Education, announced a new performance-based emplacement (promotion to a new position and salary scale) framework that enhances the career progression of nongraduate teachers. Nongraduate teachers, who have demonstrated outstanding performance, will be placed on the graduate salary scale without the need to obtain a degree. Previously, an experienced nongraduate teacher was not able to cross over to the graduate salary scale without a degree despite his or her outstanding contributions (Heng, 2014).

The second is recognition. To reward and retain outstanding teachers, MOE implemented a new Education Scheme of Service in April 2008, which set new salary ranges, variable merit increments, higher performance bonuses, additional annual bonuses, and a one-off salary increment. Teachers can also expect greater recognition in the form of additional outstanding contribution awards (OCAs). MOE also enhanced the CONNECT Plan (CONtiNuity, Experience, and Commitment in Teaching), which is a long-term incentive plan for teachers that gives teachers bonus payouts throughout their career. The new plan provides teachers with higher total career deposits, higher payouts in the first 20 years of a teacher’s career when he or she may have higher financial commitments such as raising a family, and more flexibility in terms of when teachers can draw out their CONNECT balances.

The third is opportunities. The senior specialist track (SST) has been enhanced to provide more SST posts and improved career advancement and development opportunities. MOE also provided further reemployment opportunities for education officers beyond the age of 62—those who have good performance and are physically fit to work are offered reemployment as contract adjunct teachers up to age 65. MOE has also developed a reemployment framework. Subject to availability and individual needs of the schools, school middle managers and officers at equivalent positions in MOE headquarters can also continue in their existing jobs. School leaders and senior officers may also be offered work on a project or contract basis. To help education officers with their retirement plans, MOE has put into place systemic measures such as providing a comprehensive list of jobs and assignments for officers to consider, career advancement plans, and retirement planning seminars. In addition, the Future Leaders Programme aims to develop, recognize, and retain teachers with the potential to assume key leadership roles through giving them challenging assignments and projects.

The fourth is well-being. The Part-Time Teaching Scheme (PTTS)—originally designed to allow more work flexibility for female teachers with children under the age of 6 and teachers aged 55 years or above—has been extended to both female and male teachers with children under 21 years of age. To support schools with teachers on full-time postgraduate studies, up to five more part-time teaching posts have been provided to each school cluster over and above the existing manpower grants for PTTS.

In addition, the enhancement to no-pay leave allows teachers to take time out to look after a young child or follow a spouse on an overseas work attachment. Previously, no-pay leave was only granted to female teachers for child care up to the child’s third birthday. Now this scheme has been extended to both female and male teachers to take care of their children up to the fourth birthday. Teachers can now also apply to accompany their spouse for up to four years, instead of three years in the former scheme. Teachers who are returning to work after two or more years of no-pay leave are also provided with a refresher course to ensure smooth transition back to teaching.

Having described extensively the issue of maintaining, nurturing, and retaining quality within the profession at the institutional and systemic level, we now delve into educative and developmental appraisal at the individual level.

Maintaining and Retaining Quality

The ministry utilizes the Enhanced Performance Management System (EPMS) as a structured method of appraisal that is holistic in nature and customized to the role each teacher plays on the career path she or he has selected. These are the teaching, leadership, and specialist tracks which are an important component of teacher development and advancement and are described in fuller detail in the section entitled “Professional Development along Differentiated Career Tracks.” The customizable nature of EPMS helps reporting officers (ROs), i.e., the staff’s supervisor, to determine professional development needs, promotion prospects, and annual performance grades. The appraisal parameters in EPMS are multidimensional and support three main goals: self-evaluation; coaching and mentoring; and performance-linked recognition.

Essentially, EPMS lays out a range of professional competencies as the basis for teacher appraisal and development, which specifies teachers’ performance in key result areas (KRAs). KRAs are categorized into three clusters: (1) student outcomes (quality learning of students, character development of students); (2) professional outcomes (professional development of self, professional development of others); and (3) organizational outcomes (contributions to projects/committee work). The KRAs are open-ended with no rating scale, which teachers will go through with their direct supervisors. EPMS also provides competency-based behavioral indicators to provide greater clarity on the competencies that could be observed while achieving KRAs effectively. Competency is divided into individual attributes (e.g., professional values and ethics), professional mastery (e.g., student-centric, values-driven practice), organizational excellence (e.g., visioning and planning), and effective collaboration (e.g., interpersonal relationships and skills). Evaluation results based on the EPMS system help determine teachers’ choice of career track, needs for professional development, suitability for promotion, grade of performance, and bonus compensation.

As an appraisal and development tool, EPMS functions as both a formative and summative review of teachers’ work. First, it is adopted as a self-evaluation tool for teachers. For example, it can help teachers identify areas of strength, assess their own ability to nurture the whole child, track their students’ results, review teaching competencies, develop personal training and development plans, and articulate innovations and other contributions to school development. Second, EPMS forms a basis for coaching and mentoring. The work review cycle begins with one-on-one target setting at the start of the year conducted with the teacher’s immediate supervisor, followed by a mid-year review and end-of-year appraisal. The review cycle helps specify areas for improvement and enables developmental and career pathways to be mapped.

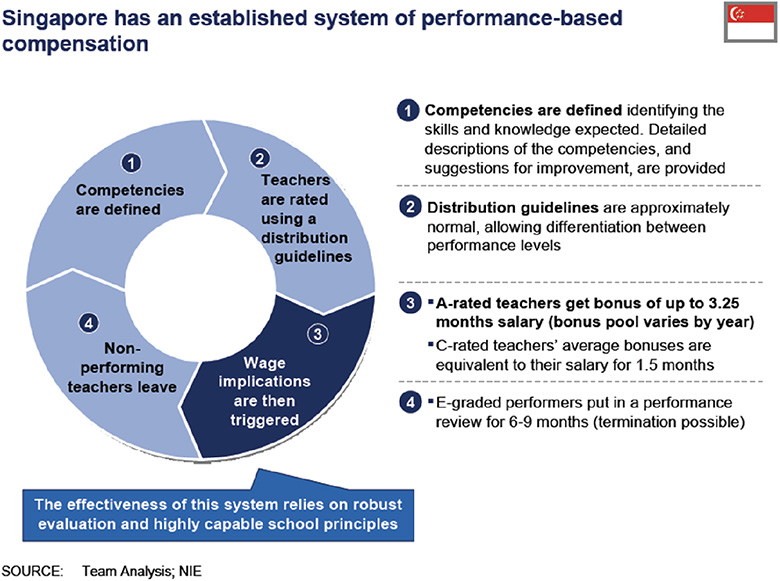

EPMS serves as a basis for performance-linked recognition in terms of retaining and growing the pool of quality teachers, encouraging innovative teaching methods, providing timely promotions for teachers with the potential for higher-level responsibilities. Performance is linked to compensation through monetary (e.g., salary adjustments) and nonmonetary means (e.g., awards such as the Outstanding Youth in Education Award [OYEA], the Caring Teacher Award [CTA], and the President’s Award for Teachers [PAT]) in order to recognize exemplary teachers in the profession. MOE also disburses grants in the form of outstanding contribution awards to deserving teachers, which could be at the individual or team level.6 Schools do not need a mechanism for preventing an explosion in salary or performance bonuses, as these are carefully managed by MOE, who directly pays all teachers. Figure 8 illustrates performance-based monetary compensation according to the McKinsey Report (2009).

Figure 8. Singapore’s Performance-Based Compensation.

Source: McKinsey and Co., 2009, p. 36

The summative appraisal at the end of the year also discusses the teacher’s future potential, known as the current estimated potential (CEP). The decision on potential is made based on evidence in the teacher’s portfolio plus the supervisor’s judgment of the teacher’s contributions to the school and community, in consultation with the senior teachers who have worked with the teacher, the department chairs, the reporting officer, the vice principal, and the principal. CEP is used to help school leaders groom potential future leaders for the system and to ensure that they are given maximal exposure to PD activities that are geared toward helping these teachers to realize their CEP.

The evidence that we have collected from schools suggests that appraisal in Singapore schools is done in an educative and developmental way. The conversation between teachers and their ROs not only covers what they have done well and why, but also the gaps and areas where improvement may be needed. The Teacher Growth Model (TGM) with its comprehensive set of necessary competencies for teacher growth often guides these developmental conversations. The appraisal process is educative in a sense that after the conversation with the reporting officer, teachers compose their self-appraisal where they write down their thoughts and plans for the future, addressing questions such as: In what ways have you improved? How you are going to improve yourself further? What are the learning activities that you would like to take on? The evaluative aspect of EPMS emphasizes teaching and learning, contribution to committees and CCAs, and vital qualities of teachers such as professionalism or integrity. The developmental aspect of EPMS (Link 13) is reflected in the sense that the conversation between the teacher and his/her reporting officer is ongoing throughout the year.

Ms. Tan Hwee Pin, the principal of Kranji Secondary School, explained:

We want to emphasise to the teachers that this is a developmental process. It is a journey and we want them to have ownership of this journey. Our HODs work with the teachers very closely and they provide feedback on a regular basis. This ongoing conversation enables teachers to chart their progress and develop their plans throughout the year.

Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor, a teacher-specialist at RGS, also emphasized the developmental nature of evaluation:

Assessment is both evaluative and developmental. The conversation is done in a very developmental way. We have our own tools such as a classroom observation tool to assess teaching competency. We also use EPMS, where we have two conversations a year with our RO. The EPMS is to document what are our plans for the year, what we have done, and the impact it has on the school or the students. It also records teachers’ training needs.

For a struggling teacher, the conversation with the RO is very important. The conversation is ongoing, done at mid-year and end-of-year. During the conversations, he/she would have been told the areas that he/she needs to improve. So a struggling teacher would at least have some kind of intervention. The RO will set clear expectations for the teacher and see if he/she can meet them in the next half of the year. However, if a teacher is struggling, it could also be due to circumstance of family and other personal matters. These will be acknowledged in the conversations as well.

The evaluation also helps teachers clarify their career options. If any is thinking of taking up a particular career track, the appraisal and development processes will help inform the areas to which teachers need to pay special attention. As she herself converted from the leadership track to the teaching track (as a senior teacher), Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin of Kranji Secondary School also shared with us how the appraisal helped her specifically to refocus on her professional development(Link 14):

At the beginning of every year, you discuss with the Head your career options for the next 3 to 5 years, taking into consideration the teacher’s performance in the previous year. That particular conversation will help you see which direction you would like to go. For example, if you intend to take up the leadership track as the Head of Department, for example, probably the school needs to expose you a bit more to different projects and responsibilities in the school. If you choose the teaching track, there are certain projects and things that you need to complete, or certain skills that you need to have before you can get to be promoted to the Senior Teacher position.

When I was on the leadership track, I was doing more of activity organisation for the students at the departmental level and was not very involved in mentoring teachers directly. So with the appraisal, I could narrow down the kind of skills that I need to mentor the teachers and exactly how I can improve on my mentoring of the teachers. Rather than being the authority figure, I have to become more of a teacher mentor. There is a stark difference between a leadership position and a senior teacher position. A senior teacher is one whom teachers find approachable in talking to and comfortable getting advice from.

Independent schools do follow the MOE EPMS system. However, the system is adapted to suit the needs of the unique context of independent schools, where the expectations and roles of teachers are quite different from mainstream government schools. For example, in RGS, the lens that is adopted to appraise teachers is their ability to motivate the high-ability girls. Therefore, the appraisal places more emphasis on advanced content, higher-order thinking and processes, and conceptual learning. Its format is similar to MOE’s, which includes performance planning at the beginning of the year, mid-year work review, and year-end work review. These procedures are essential steps in helping teachers understand where they are in terms of their own development and performance.

The appraisal system in independent schools is also generally divided among the different career tracks, namely, the teaching track, the leadership track, and the teacher specialist track, yet with small differences. For example, in RGS, the specialist track is different from that of the MOE. While MOE’s specialist track is only for those who specialize in a specific area and do not teach in classrooms, the specialist track in RGS does include teachers. However, at RGS, teachers in the specialist track are partially released from teaching, and the freed-up time is used for educational research. Therefore, these teachers are specialists in education research. Still, many MOE specialists are teachers by training. Once they are on board the specialist track, some are given opportunities to pursue their PhDs.

Besides EPMS, independent schools also develop their own tools for assessment. For example, RGS developed a classroom observation tool to assess the teaching competency of classroom teachers. According to this tool, there is a certain benchmark score for teachers. While the benchmark is lowered for new teachers, it is higher for experienced teachers who have, for example, more than five years of teaching experience. It documents the behavior of the teacher, including relationships with the students, and lesson delivery. In addition, it also documents how the teacher performs during school functions and CCAs. As Mrs. Poh Mun See, the principal of RGS, explains:

We do follow the MOE system for performance management. For example, we do performance planning at the beginning of the year, followed by mid-year work review, and year-end work review. This is because these are the essential steps in helping teachers understand where they are in terms of their own development and performance. But we have adapted the competency framework to suit our needs because the expectations and roles of our teachers are quite different.

This section has focused on the educative and developmental appraisal at the individual level that ensures that the quality of each teacher is continually upheld. The next section will cover the final theme of this case study to demonstrate how professional teacher learning is undertaken at the systemic level.

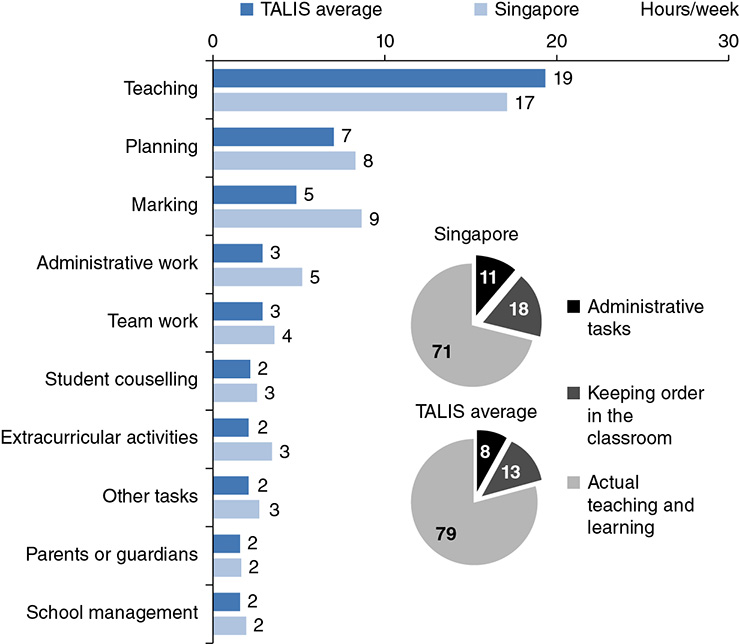

Professional Learning beyond Induction

Beyond the “hand holding during the first year or so” that “helps to prevent the early exit of freshly trained teachers,” there is “a comprehensive framework to provide different pathways for teachers to upgrade themselves” (Goh & Lee, 2008, pp. 102, 105). The professional development of teachers is an essential aspect of the national agenda, as evidenced by the government’s “move towards an all graduate recruitment by 2015” and the goal for “30% of the teaching force [to] have Master’s degree qualifications by 2020” (Goodwin, 2012, p. 39). Distribution of the working hours of a Singapore teacher is shown in the following diagram (Figure 9), taken from the TALIS 20137 report. The report indicates that teachers spend 71% of their lesson time on actual teaching and learning (self-reported data). In addition, TALIS for 2014 (OECD, 2014b) shows that teachers in Singapore have higher than average national participation rates for a number of PD activities such as courses and workshops (93%), education conferences (61%), in-service training in external organizations (17%), network of teachers (53%), and individual and collaborative research (45%).

Figure 9. Teachers’ Use of Time: Singapore-TALIS Comparison Data.

Source: OECD, 2014b, p. 3

The actual timetable of Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin (Figure 10), the teacher we video-recorded at Kranji Secondary School, offers a more concrete idea of how a Singapore teacher’s working time is divided. Rosmiliah’s timetable is very representative of the TALIS data. For example, most of her time is spent on teaching her secondary 3 and secondary 4 classes. She has a blocked time on Thursday for professional learning and development, which includes BT mentoring, professional learning communities, and Learn and Grow. She is also involved in cocurricular activities. Her administrative work is allocated in staff and department time (SDT) and department meetings (RCP). From the timetable, we can clearly see the importance of teaching and professional learning in her daily work.

Figure 10. Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin’s Timetable in Semester 2, 2014.

All teachers are entitled to 100 hours of paid PD annually that is considered “office time” and therefore can happen during school hours with additional manpower resources provided via “relief teachers.” But PD is more than the acquisition of new skills or training, but aims to reshape the nature of teachers’ work and to enhance their professionalism. Teachers have about 17 hours of timetabled teaching periods per week, as shown in the TALIS results. They can make use of their nonteaching hours to work with other teachers on lesson preparation, visit each other’s classrooms to study, teaching, or engage in professional discussions and meetings with teachers from their school or across schools in learning communities. Teachers are also supported to conduct action research, lesson study, or other teacher inquiry projects in small professional learning teams. They may examine their teaching practice and student learning so as to foster more effective and innovative teaching practices, and develop curriculum resources for their departments and other teachers. Protected time is set aside in the timetable to sustain these types of collaborations. In this regard, the SSD in each school plays an important role in customizing professional learning to teacher needs and school goals. They are also in charge of planning and implementing whole-school professional learning programs with teacher leaders.

School leaders in Singapore strive to create a conducive professional learning environment for teachers. The latest TALIS results provide some concrete evidence on this area (OECD, 2014b). For example, the results show that almost all schools in Singapore provide teachers the opportunity to actively participate in decisions. In addition, 8 in 10 principals will place their emphasis on making sure teachers take responsibility for their professional learning and students’ learning outcomes. From the perspective of teachers, 81% of them feel that their schools have a collaborative culture that is respectful and mutually supportive. The study also found that the collaborative professional learning culture and opportunities to participate in school decisions are positively correlated to job satisfaction.

Just as with initial teacher preparation, NIE and MOE work together synergistically to meet teachers’ educational and professional needs, to support teachers’ advancement, and to respond to national, as well as a plethora of ad hoc, imperatives and goals. Thus, NIE offers a variety of workshops to enhance teacher learning about the new assessments that support MOE initiatives in that direction. NIE also offers degree and diploma programs for school leaders, senior teachers, and content specialists, while the MOE has made it easier for teachers to be temporarily posted to NIE as teaching faculty for up to four years (a practice known as “secondment,” which previously was only available to independent schools or the ministry), thus opening yet another PD route for teachers to learn and grow, and creating yet another mechanism for NIE and schools to be mutually informing and collaborative.

The school year in Singapore is from January to December each year. There is a total of 12 weeks of school holidays a year, which teachers can enjoy if their services are not needed during the holidays. They may use this period for overseas travel, etc. Teachers also have fully paid ordinary sick leave up to a total of 14 days in a calendar year or 60 days if he/she is warded in a hospital. Teachers are entitled to urgent private affairs leave for up to 10 working days per year. In addition, MOE has implemented other pro-family schemes such as full paid childcare leave and parent leave. The ministry also provides funding for scholarship and study leaves—both locally and abroad—facilitating teachers’ movement along selected career ladders and learning along multiple dimensions. MOE’s PD packages and leave scheme offer various types of scholarships, study loans, and leave provisions, which allow teachers to further their undergraduate/postgraduate studies in various areas. For instance, a teacher could take a study leave to attend university in another country or could take a study leave to intern at, for example, a local gallery to learn more about art in communities. The application for study leaves and scholarships is based on interest, experience, and merit, and there is no competition among teachers.

For example, Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin participated in an overseas learning program in the United Kingdom, which was a three-week course on geography that combines theoretical learning and field work. The program was organized by MOE. Teachers who are interested can apply with their school leaders’ recommendations. At RGS, Mrs. Mary George Cheriyan has always been interested in the principles behind policymaking and national issues. As the then director of academic studies and a member of the senior management, she was granted a scholarship and one-year study leave by RGS to pursue a master’s in public administration (Link 15) at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. She shared with us that the learning experience helped her understand some of the key principles in policy and reform, as well as how to utilize human capital to achieve certain objectives. What she learned helped her greatly in setting up PeRL in RGS, which not only aims to support the professional learning of teachers in the school and Singapore but also aims to contribute new knowledge to the international education community. She said

I was able to ask, what are my objectives in setting up this centre? What are some of the overarching goals? I had to view it not just as a centre within the school, but as something that can have greater impact within the fraternity in Singapore and beyond. As the Lee Kuan Yew school has a very strong Asian narrative, it is very focused on the Asia-ness of our thinking. I came back [with strong convictions] about that. One of our aspirations of PeRL is to cultivate an Asian discourse on education.

A series of system-wide strategies were also established to attain the vision of teacher-led professional learning. First, platforms for teacher-leaders to lead professional learning were created via subject chapters, professional networks, professional focus groups, and professional learning communities. Teacher leaders support teachers’ professional learning within and beyond the schools to the entire teaching fraternity. There are three essential aspects in the role that teacher leaders play: (1) pedagogical leaders, (2) instructional mentors, and (3) professional learning leaders. As pedagogical leaders, they are experts in the teaching and learning of their subject disciplines; as instructional mentors, they facilitate the development of less effective teachers so as to help them become more effective; as professional learning leaders, they plan and facilitate professional learning activities for teachers in the fraternity. For example, professional learning communities are set up and led by teacher leaders to facilitate teacher collaboration focusing on pedagogical innovation and subject mastery.

Second, strong organizational structures for professional learning were developed, among which are training entitlements for teachers; funding for MOE-organized courses; timetabled protected time for teachers to engage in lesson planning, reflection, and PD activities; and an online portal providing one-stop access to learning, collaboration, and resources for all MOE staff.

Third, a number of initiatives to preserve and grow the values, beliefs, and practices of the teaching profession were introduced. The Ethos of the Teaching Profession was established and the MOE Heritage Centre was set up so that a slice of the past could be displayed to remind and inspire teachers. Awards and recognition for teachers were also created to recognize role models in education.

Among the many investments is the Teachers’ Network, so named in 1998 by MOE as part of the TSLN initiative. The mission of the Teachers’ Network is to serve as a catalyst and support for teacher-initiated development through sharing, collaboration, and reflection. The Teachers’ Network was reconceptualized to be AST in 2009. AST was started to spearhead the PD of Singapore teachers. It was envisioned to be the home of the teaching profession and help catalyze teacher capacity-building. The AST mission is to build “a teacher-led culture of professional excellence centered on the holistic development of the child” (AST, n.d.c.).

AST was founded to also pull the master teachers together to support their learning and to enable them to organize professional learning for others. There are currently 76 master teachers and principal master teachers in the academies and language centers.

Ms. Cynthia Seto, a principal master teacher for mathematics currently assigned to AST, shared her view of the academy’s role as facilitating the spread of good practice:

I see the set-up of Academy of Singapore Teachers as encouraging teachers to take ownership and teacher leadership of their professional development. It provides opportunities for teachers to collaborate, to interact with teachers from other schools. I was a senior teacher for seven years before I became a master teacher. In my previous school, there were three senior teachers, including me. Although we worked together in mentoring teachers, we were from different subjects. The opportunity to interact with senior teachers teaching the same subject is important to deepen our pedagogical content knowledge and teaching practices. I feel that the academy is well situated to bring about this kind of collaboration, to spread good practices across schools.

Right now, my first goal as a master teacher is to raise the professional standards of the mathematics chapter. . .To do that, we conduct workshops [and] provide an opportunity for workshop follow-up for sustained learning. . . I see myself as a catalyst to encourage teachers to form networked learning communities (NLCs) for us to talk further about what we are doing, for everyone to reflect on our practice, and to share effective strategies to meet the diverse learning needs. We want our students to learn mathematics with understanding.

We could come together to co-design a lesson and then look at how it works in the classroom. After the lesson observation by teachers, we will reflect and discuss. It may not be a perfect lesson, but it’s an opportunity for learning. Teachers [may say], “Hey, I’m going to do something like that in my own class,” and then they’ll bring it back to try in their own class. It could be in the form of a video, it could be in the form of a student artifact. . . It is encouraging to hear teachers saying “Oh, my students, this is what they have done. Oh, your school does this like that? Mine is like that. Oh, we could do something, you know?”

With regard to AST’s vision of shaping a teacher-led culture of professional excellence, Ms. Irene Tan, who is also a principal master teacher at AST, shared how teacher leadership is emerging:

When we first started the academy, we wanted to create a teacher-led culture to raise the professional standard. Because of the fact that we are master teachers, we are expected to lead the chapter. We are trying to also empower the next level, which is the core team members. We have a subject chapter led by master teachers, then we have the core team. The core team is made up of senior teachers and lead teachers from different zones (north, south, east, west). In my team, we have ten of us.

Previously, my colleague and I, who is also a master teacher, were leading and planning. Starting this year, 2013, I actually see that the [core team members] are taking the lead. They are the ones who say that, “Irene, besides doing this, can we consider also to share with the beginning teachers, for example, how to conduct a chemistry practical lesson properly?” Because when they come in, one of the biggest learning gaps is that they’re not confident to bring a class of 40 students into a chemistry lab. It’s a little scary and daunting for them because of all the chemicals and the classroom management and the potential safety issue, so they’re a little scared. The senior teachers have come together and they volunteered to do zonal workshops. They’ll sit down and plan. Come next month in November, my colleague and I will help look through the workshop material and then we’ll give them the full support.

They are the ones who identified the learning area for other teachers and they’re planning these things for the teachers. I see that teacher leadership coming up very strongly. Science experiments is not the only area they have identified. One group will look at misconceptions in chemistry and they would like to use lesson study to try it out. Another group is looking at helping teachers look at item setting for database questions, for example. That is for the chemistry syllabus. They are trying to involve senior teachers beyond the core team. We’re reaching out to the second tier.

Together with the emerging teacher-led culture of professional learning is the change in teachers’ views on teacher leadership and their increasingly strong identity of being teacher leaders. Ms. Cynthia Seto and Ms. Irene Tan shared with us:

The teachers gave feedback to me that they’re more confident, especially the senior teachers, because the PD activities are very practice-based. At the same time, it’s very relevant to their role and to their classroom teaching. With the support given, they are more confident, and they know that if there’s anything that they are unsure about, they know where they’ll go to. That is important. They get affirmation from their fellow colleagues, as well as from the academy itself.

With the setup of AST, they have more opportunities to play their role as a teacher leader and also to reach out to play a more significant role in the professional development of teachers and be able to talk with colleagues. So they find that there is something they enjoy and they feel that they are contributing, they are being part of that community. I think the sense of community is stronger now.

The identity of the idea of senior teacher [is stronger now]: the lead teachers also see themselves as teacher leaders. For the longest time, the term teacher leader usually referred to heads of department and vice principals who are in-school leaders. [Senior teachers] see themselves as teacher leaders now. Not only we [at the AST] give them a platform to share with other teachers, one of the things that we consciously look into is to build the capacity of this group of senior teachers as well. As they help others grow, they themselves will grow.

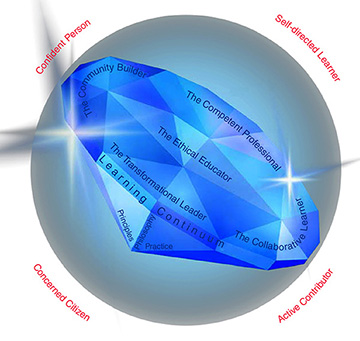

In addition to AST, other academies and language centers were also set up to support subject-specific professional learning. The Physical Education and Sports Teacher Academy (PESTA) and the Singapore Teachers’ Academy for the aRts (STAR) both support teacher learning in those subjects, plus the English Language Institute of Singapore (ELIS) provides PD for English Language teachers; additionally, the Malay Language Centre of Singapore (MLCS), the Singapore Centre for Chinese Language (SCCL) and the Umar Pulavar Tamil Language Centre (UPTLC) support development for Malay, Chinese, and Tamil language teachers. To support PD planning for in-service teachers, the Teacher Growth Model (TGM) was developed as a learning framework with desired teacher outcomes (Figure 11). The TGM learning continuum is organized according to five teacher outcomes: the ethnical educator; the competent professional; the collaborative learner; the transformational leader; and the community builder. Under each teacher outcome are the skills and competencies required for growth and development so that teachers can achieve all five teacher outcomes. Teachers also use TGM to examine their professional learning needs. Learning programs and activities are themed according to each outcome and competency. Teachers can choose the area that they want to enhance and participate in the corresponding professional learning programs targeted at that area. Learning and development occurs in a variety of modes, such as courses, mentoring, e-learning, learning journeys, reflective practice, and research-based practice.

Figure 11. Teacher Growth Model.

Source: MOE, 2012b

Professional learning activities (Link 16) are centered around providing holistic programs and environments to facilitate the holistic development of the students along multiple dimensions, including the cognitive, physical, social, moral, and ethical dimensions. As the key to successful facilitation of students’ holistic development, teachers’ professional learning is one of the most important priorities on school agendas. Schools strive to build a strong culture of professional learning, manifested through various professional learning activities such as SMP and professional learning communities. The following are some noticeable highlights in terms of PD.

1. Research and Teacher Inquiry

As practitioners, almost all teachers are involved in research and innovation projects examining their teaching and learning to better meet the needs of students. Teachers are not only supposed to be competent in teaching, but also to become reflective practitioners through research and co-learning. Schools provide structured time for teachers to come together as a group to discuss and implement their projects. Teachers may choose to use a variety of teacher inquiry approaches—action research, lesson study, learning study, and learning circle—to investigate their practices. To facilitate teachers’ development of research competence, support from internal and external educational experts is provided for teachers. Over the years, teachers’ skills in terms of using research to gather data and evidence to make informed decisions have grown. Research findings are also shared through various platforms at the departmental and school levels, other local schools, and local and international conferences. Each year, the school may have different topics and areas as the research focus, topics which are collaboratively identified by the senior management and teachers as a whole. When teachers feel that the structured time is not enough to discuss their projects, they will come together on their own initiative whenever they feel it is needed, either within the school day or after it. The research projects are not only done at a subject level, but also go beyond specific subjects to involve collaboration among different departments and disciplines. It is important to note that while a significant proportion of teachers do research, others are doing smaller or developmental projects that may not involve a full-blown research protocol but are nevertheless designed to collect evidence to support the improvement of their teaching and learning.

Ms. Tan Hwee Pin, the principal of Kranji Secondary School, shared with us how research is highlighted and encouraged in professional learning(Link 17):

All our teachers have to come together to work on a research project where they get together in small groups to solve a teaching and learning issue—it can take the form of a lesson study, action research, or innovation project. We set aside structured time for the groups and they have one year to complete the project. At the end of it, each group will have to present their project to fellow colleagues during Staff Innovation Day. We invite professional judges to select the best entries, and we have seen a couple of great ideas emerge from this exercise. I believe that this research process motivates our teachers to be more reflective and critical of their practice and strategies.

Mdm. Rosmiliah Bte Kasmin and her team from Kranji Secondary School embarked on an action research project in 2014, where they looked at the effectiveness of using a particular ICT tool in teaching. This project compared two groups of students: one group was exposed to the ICT tool, whereas the other was exposed to the typical way of teaching. From this project, the team was able to explore the use of the new ICT tool to facilitate teaching and learning. The evidence gathered from student surveys indicated that students found the ICT lessons more engaging and fun. The use of the ICT tool also allows students to do more in-depth study around the concepts and relationships they are learning.

Teachers are well supported by the schools to conduct research projects, not only in terms of resources and methodology, but also in terms of dissemination of research results in different platforms. As Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor at RGS explained:

On top of the opportunities to attend workshops, there are opportunities to attend conferences or even to present papers at international conferences. These presentations involve teachers at RGS doing their own research or research on program evaluation. It is supported by PeRL in RGS, where they have expert teachers to guide us in terms of how do to research. When teachers propose a research project, they will assign one expert for teachers to get feedback and alternate views.

Emphasizing the importance of research to a teacher, Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor added, “This is not just about being a competent teacher, but also about the teacher as an inquirer and reflective practitioner of their own craft.”

The professional learning of teachers impacts not only teachers’ professional growth but also students’ future learning experiences. The following vignette of Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor’s practitioner inquiry (PI) project demonstrates how teacher professional learning and students’ learning can be seamlessly connected. Practitioner inquiry in RGS is based on a shared vision of knowledge creation and sharing at the school and the aim of improving teaching and learning (Tan, 2015).

However, teachers also shared that the biggest challenge of conducting research is time. As a result, teachers have to also utilize their own time for collaborative work and research, which in a way reflects Singapore teachers’ devotedness and professionalism.

2. Sharing of Expertise and Knowledge

Teacher leaders in the school conduct workshops to share teaching strategies. They use concrete examples to explain and model the strategies. Teachers attending these sharings discuss and reflect on the usefulness of these strategies in their own classrooms and how they can customize them for their own students and subjects. Through this, the entire fraternity can be exposed to new ideas and strategies, which ultimately benefit students’ learning. As commented by a teacher we interviewed, “when the teachers learn new skills and try out new activities and pedagogy, it would actually allow the students to be more engaged in class and even get a different perspective of understanding.”

While senior teachers and master teachers play an important role in teacher capacity building within schools, their PD is also well taken care of by the system. One important platform is the cluster system of schools, which normally has about 10–13 schools, across levels (primary, secondary, and junior college). The cluster system provides a professional learning platform for teacher leaders that can help to build their leadership capacity so that they can, in turn, build the capacity of teachers in their schools. Ms. Irene Tan, a chemistry teacher and now a principal master teacher with AST, used to work in the cluster system of schools. She explained:

In my cluster, I had 13 schools and my office was in one of the schools. I had the autonomy to work with the teachers as well as the heads of department and the vice principals in areas that they wanted me to look into: for example, mentoring or hand-holding the new key personnel, because I was a head of department for 13 years before I became a master teacher.

I also worked with the experienced teachers as well as senior teachers. I belonged to the senior teacher guild in my cluster. [This is] where all the senior teachers in the cluster will come together. They usually have a chairman to head the professional learning so they will chart out the year’s learning.

For example, they will organize for each other one or two learning journeys, some sharing sessions, and workshops where they will invite others to come in. Basically, they look at their own learning needs. For example, if this year the guild feels that most of our senior teachers are very interested in looking at assessment, they’ll try and source for a speaker or somebody relevant to run a workshop for the senior teachers. As they build their own capacity, they can then share this knowledge and experience with the new teachers in their school.

3. Create, Implement, and Review Cycle

The school professional learning activities follow a cycle where teachers collaboratively create and design the strategies they are going to use in the classroom, and then implement them in their classrooms, followed by reviewing the implementation and making improvements for the next implementation. This particular cycle enables teachers to get together and consider lesson innovations, and talk about the impact of their practices on students. It enables continuous improvement based on evidence gathered from students’ responses. For example, as Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor described:

About five or six years ago, we introduced something called article analysis, where students have to critique an article. We realised that it was a big jump for the students. For the last two years, my team and I have used a new assessment for article analysis. We use argument mapping in which students have to read and map the argument first, before they evaluate an argument in an article. This is an example of the cycle of designing implementing and reviewing. This whole process allows our teachers to have a sense of ownership and autonomy.

Teachers in RGS continuously create and experiment with their teaching. Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor shared with us how his team has implemented a new tool in their teaching and how that brings them enjoyment:

We discussed in our last Professional Learning Space (PLS) about portfolios. The good thing is that the team thinks, “Let’s do it. Let’s find out more about how portfolio looks like, and maybe this year we can experiment.” That’s something that I really enjoy here, because you can experiment. If it doesn’t work, it’s okay. We get the team on board to work on it.

4. Collective Responsibility

The professional learning activities are intended to involve the entire faculty in the school, from the principal and senior management, to each and every teacher. In other words, it is not just teachers who will sit down to discuss their lessons, but members from senior management will sit down with teachers as peers to listen, discuss, share their experiences and ideas, and contribute their expertise. The dedicated time for professional learning and the involvement of senior management greatly encourage the teachers to take these learning opportunities seriously.

Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor talked about how RGS school management emphasize professional learning:

What I like is that when we have a dedicated time, it’s a message that the time for Professional Learning Space (PLS) is important. I must say that the senior management take the PLS sessions very seriously. They join us, even the principals. They take it seriously, and we take it seriously as well.

Mrs. Mary Cheriyan elaborated on how the school takes professional learning as a collective responsibility (Link 18):

PLS is collective responsibility. During this time, the entire faculty—right up to the principal, the entire senior management is involved. It is not just teachers who will be sitting down to discuss the lessons. I will sit down with teachers as peers to discuss what are some suitable strategies, what worked, what didn’t, and bring whatever I can contribute.

The collaboration among teachers often goes beyond departmental level boundaries. Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor told us about a project in RGS involving the collaboration of three departments—English, Social Studies, and Philosophy:

We want the girls to be an advocate and an active citizen. So we decided to introduce a project called the advocacy project for active citizens. It was a collaborative project among three departments including English, Social Studies, and Philosophy. The girls will undertake an advocacy project. They were assessed by three different departments. The language department will look at their use of language in terms of how persuasive they were in their advocacy speech; the Social Studies department will look at their thinking process, their process of advocacy and research; the Philosophy department will look at what are the questions they use.

Besides conducting research, different departments also meet to discuss other issues concerning teaching and learning.

5. Networked Learning Communities

Networked learning communities (NLCs) are platforms offered by AST where teachers across schools come together to learn and work collaboratively on professional areas of interest. For example, there are NLCs (1) that are subject- or role-specific (e.g., NLCs of SSDs; NLCs of allied educators), (2) that cater to specific interests (e.g., an NLC of inquiry into lesson study).

Ms. Irene Tan described how academy leaders help organize other lead teachers from the field by subject area and how workshops are designed to create applications to practice.

Basically, in a subject chapter, the senior teachers who represent the different zones will come for meetings and consultation with us. Then we find out from them what their learning needs are before we even conceptualize and mount any workshop. We hear from the senior teachers, “Oh, my BTs actually need these areas of training.” Then that’s where we come together and then we design workshops for them. . . Where possible, teacher PD should be just in time and sustained and on the job, so that’s why we are working through the senior teachers.

The way we design our workshop, we affectionately call it a five C approach to teacher PD. The first C is actually curiosity. That is to pique the teacher’s sense of curiosity to want to know more about the workshop. The second C is about comprehension. It’s to get the teachers to understand and know about the new pedagogy or teaching strategies. The third one is to convince. During the workshop, we will try to share with the teachers not just how it is done, but why it should be done that way and what are some success stories to try and convince the teacher that this is the way indeed to go forward. The fourth is contextualization. We give teachers the opportunity to work on something. Let’s say they come for a PBL workshop and during the day, we will give the teachers time to work in team to craft a problem scenario and prepare the lesson, so that when they go back to the school, they can actually carry out the lesson plan or the unit plan with their students. The last C is “change practice.” Then, they always come back for a celebration, so that’s [an additional] C. When they come together, they will present their teaching ideas and then how they have tried it out with the students and what are some of the learning points. What do they see in their students and how do they feel as a teacher after carrying out the whole thing and whether or not this can be sustainable in their point of view.

A typical NLC that is based on teachers’ specific interest is one on lesson study. Teachers can refine their lesson study practice with help from their teacher leaders in schools (i.e., senior and lead teachers) and master teachers at AST. Ms. Irene Tan and Ms. Cynthia Seto together described how teachers are supported to learn lesson study through workshops and networked learning community:

For lesson study [workshops], we encourage schools to send a group of at least three teachers so that they have each other’s support during the journey. There are usually three to four face-to-face sessions in the lesson study workshop. The workshops are usually conducted in a blended manner where resources and reading materials are placed in an online learning platform. The teachers can then read and participate in discussions on the online forums. This will provide the teachers with some idea of what lesson study is and for them to have a professional discourse.

The first face-to-face session is where we facilitate the learning of the what and why of lesson study as well as how the research lessons can be designed. In the second session, they go more in-depth into the lesson design and planning. The teachers are also given ample opportunities to provide feedback to each other. We then refine the lesson plan and one of the teachers will teach it with the rest observing in a classroom. The lesson observation is the third session of a typical workshop. The master teachers facilitate both the pre- and post-lesson discussions so that the teachers can observe how facilitation is carried out. In the fourth face-to-face session, all participants come back and share their lesson study experience in terms of planning, implementation, and learning (both students’ and teachers’).

And, we do not stop there. We encourage them to form a lesson study NLC. The NLC [offers] a more fluid approach in the sense that the members will direct what, when and how they want to do. The NLC members plan lessons together and they can conduct the research lessons in their respective schools or they visit one of the member’s classroom to observe the lesson.

6. A Discipline-specific Approach

Another area that impressed the research team of the Singapore approach to professional learning is the emphasis on a discipline-specific approach that develops pedagogical content knowledge. From Ms. Irene Tan:

More often than not, the teachers will continue with lesson study . . . in their own department. One of the reasons I see this [is that] our lesson study approach has not been in a generic manner. When we conduct these series of workshops, like four afternoons for the teacher, we do it by subject. For example, if I do a lesson study workshop, it’s for chemistry teachers only. Cynthia would do [a workshop] for elementary maths teachers. The conversation is very rich in terms of content.

[We rely on] the signature pedagogy that comes with this particular subject: maths has a way to teach mathematics. Science, there’s a way to teach science. It is very different from the generic one way when they just talk about lesson study. Then they may not have the opportunity to go very deep into the content. For us in AST, we have the luxury of a few of us all doing lesson study. Then we can really tailor the discussion to the subject.

7. Ample Professional Learning Opportunities beyond School

Teachers are encouraged to pursue professional learning beyond their school boundaries based on their interests and passion. For example, they may apply for no-pay leave to pursue their masters. Teachers can also go for workshops or conferences outside the school.

8. Cultivating an Asian Perspective

Many teachers in Singapore are cognizant of the limitations of theories and practices in Western countries and aspire to cultivate a confident Asian discourse on education. This is one of the important aspirations of PeRL at RGS.

9. A Systemic Approach

One highlight of the systemic approach is the role of the SSD. Every school has an SSD, an equivalent to a head of department, whose job is to ensure that the training and professional development programs are customized to the needs of the teachers in school and support the school’s goals. The SSD, in consultation with the school leaders, is in charge of drawing up a whole-school staff development plan and also working with individual teachers to draw up their own training plans. The SSD also taps the expertise of the teacher leaders to facilitate teacher learning through mentoring, formal courses, and learning communities. Therefore, the SSD plays an important role in helping every teacher progress continually in her/his professional development and establishing a culture of collaborative learning to achieve the desired school outcomes.

A second highlight in the systemic approach is that the professional learning is holistic and systematic at both the school level and the individual staff level. For example, in RGS, every year there will be a total professional learning plan for each staff including teaching, nonteaching, and key personnel. Their professional learning activities are differentiated according to their own needs. Professional learning is not a one-week or one-month event, but an ongoing process throughout the year. Every year there is a different focus, for example, critical thinking, infusing ICT into classroom, or formative assessment. However, different topics from year to year are not separated, but integrated in the sense that when new topics are introduced, the former topics will still be present in professional learning activities in one way or another. In addition, former foci and topics will be put into the appraisal processes of teachers.

10. Student-Centered Professional Learning

The design of professional learning opportunities is student-centered. Given this philosophy of catering to students’ needs, teachers are not afraid of asking themselves difficult questions. One important question that teachers ask is “What is my contribution to students’ learning?” Student feedback is often sought to review the teaching and learning processes. (Link 19) For example, at one professional learning session that the research team attended at RGS, the Social Studies department was discussing students’ complaint about having too much reading. Mr. Azahar Bin Mohamed Noor shared with us how RGS engages students in giving feedback to the school:

The school engages the students in terms of teaching and learning, CCAs, and other issues. There is a student body called the “Congress,” which gets feedback from the student body. It is quite common that students’ feedback is channeled to the congress, where some of the students’ feedback will be conveyed to the school management. The school management will then inform the staff. And we will discuss the students’ feedback at the teachers’ level. So there’s a lot of dialogue and engagement with students with regard to our programs and policies. Another channel of feedback is the survey with students. This is called the RGS experiential survey, where students give feedback to the teachers teaching them directly. It is done twice a year. Through this, we get feedback on whether they enjoyed their learning, and whether they were sufficiently challenged.

11. Finding Time

Teaching is becoming an increasingly challenging profession. Together with various kinds of educational reforms and initiatives, it is common that teachers are taking on more and more responsibilities and heavier workloads. To ensure effective professional learning, it is of critical importance that schools structure protected time for teachers to learn. The school leaders in Singapore are well aware of this. Ms. Irene Tan shared with us the approach of the school where she was formerly posted:

From the school I came from, we used to have weekly contact time with the staff. What we did was, we didn’t use the contact time to do administrative things. We tried to convert the contact time, which is usually about two hours per week, into professional learning time. Besides that one hour timetabled time, we have two more hours freed up because the school leader felt that, “Well, some of these things I can communicate through emails and though electronic means.”

So we can creatively cut down some things to create time for teachers to come together. But the timetabled part is good because during curriculum time, we can have a time slot for all the teachers in the team to meet. In a sense, it is good because we know for sure that on this weekday at this time, say Wednesday 10:00am, we are all free for that one hour. If we really want to do a research lesson for our lesson study, we can actually go into a class and conduct [the lesson] and we know that we are all free during that period.

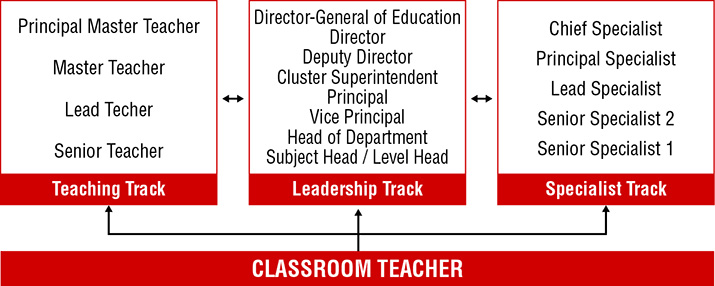

Professional Development along Differentiated Career Tracks

In tandem with the wide range of PD opportunities open to teachers, there are clearly differentiated career tracks that allow for career progression along the areas of strength displayed by each teacher. The concept of a teacher’s career ladder is well developed in Singapore, offering teachers different routes for advancement and leadership. While the traditional role of the principal as the main school leader still predominates, leadership has become a much more distributed concept where it is being devolved or shared across the institution (Spillane, 2005). MOE developed Edu-Pac (Education Service Professional Development and Career Plan) (Link 20) “for teachers to develop their potential to the fullest” (MOE, 2009).