But historical beginnings are lowly: not in the sense of modest or discreetlike the steps of a dove, but derisive and ironic, capable of undoing every infatuation.

Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History”1

Naturalizing Muslim Pain

Why has injury come to govern so much of the contemporary academic discourse about Muslims? Why are pain and hurt the affective labels by which the outrage of some Muslims over disrespect for Islam are represented? Why is the response to what is loosely termed “blasphemy” used to constitute a Muslim polity by people who claim to represent “the Muslim community” and also, more surprisingly, by academic theorists? The quick answers that suggest themselves seem both obvious and inadequate: Hurt expresses the effects of the relentless racism and xenophobia faced by many Muslims in the West. It does not take much to see that after September 11, 2001, the word injury, even when conceived as discursive or “moral,” implicitly summons connotations of the physical wounds inflicted by Western-led wars on a range of countries in which Muslims are a majority. Injury and pain are the conditions of Muslims in Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia, and parts of Pakistan.

Moreover, in the academic context, in the age of identity, Muslims have to be identified by some act of affiliation. But since Muslims have now become the intellectual object against which practices assumed to be constitutive of the modern secular order are critiqued—perhaps even constituted—a mode of identification and (communitarian) subject production has to be found that cannot be coded as “choice.” For “choice” is an umbrella word by which a cluster of modern fictions—individualism, neoliberal economics, the free market—that sustain the structure of a globalized, increasingly homogenized and fundamentally inequitable late capitalist modernity are now organized together. In what one might consider the philosophical slang of capitalism, one chooses to be poor, deprived, or politically oppressed. Capitalist modernity is like the abusive lover who beats his beloved, tears streaming down his face, claiming with every brutalizing blow, you make me do this and you can stop it any time. Academic antiliberalism thus requires a way of coding Muslim affiliation in a form that cannot be read as choice; “injury” can do this work. “Injury” makes identity ontological, without being, as we shall see, precisely biological. The one word can encompass the spectrum of violence against Muslims and link that violence, discursive and physical, in a form that then speaks to the ontological status of Muslims. When adduced in response to what is sometimes called blasphemy, injury is able to connect the discursive and unbodied representational and semiotic acts that might be construed as attacks with the affective response of hurt, to enable a slide from discursive injury to embodied response.

The aim of this chapter is to think about the transnational, indeed planetary, effects of linking injury, blasphemy, religious pain, and Muslim identity together. One effect might already have become visible: Injury and pain are also the conditions of Christians, Hindus, and Jews in countries bombed by the coalition, but I have hidden the violence inflicted by Empire on non-Muslims (even the description non- produces them only through negation) in “Muslim” lands in the way I have begun this chapter. Daisy-cutters, depleted uranium, and cluster bombs are no respecters of religious difference; they do not inquire of bodies, before they tear them apart, whether they are atheist or Christian, or Bahai, or Muslim, whether they are secular, or “post,” but in bringing together religious pain, identity, and empire in my framing of the problem, I have replicated a civilizational divide and erased the violence done to minorities in these lands.

Let me begin by looking closely at two academic representations of the varieties of Muslim hurt. One is a consideration of Muslim responses to the Rushdie affair and another to the controversy surrounding the Danish cartoons. Both are concerned with the specificity of Muslim pain in response to insults to the Prophet of Islam.

But, first, a caveat is in order: It is crucial to distinguish the two controversies, even as furor subsequent to the publication of the Danish cartoons followed patterns established in the Rushdie affair: the riots, death threats, assertions of the embattled, intrinsically European virtues of free speech, counter-assertions of the European blindness to Europe’s own taboos (witness, the critics of the free speechers would say, the crushing oblivion meted out to Holocaust deniers), the travel of Islamists from Europe seeking solidarity in rage from Muslims elsewhere. The mockery in the cartoons is distinct from the use of a novel, by racists, to goad Muslims enraged by an “apostate” Muslim who had written a novel about apostasy and the destruction of a believer’s mind upon thinking the unthinkable, by thinking, in other words, the prohibited thoughts that can lead to apostasy.

The first example I want to consider is Tariq Modood’s discussion of Muslim pain in an essay first published in 1990 and reprinted in Multicultural Politics: Racism, Ethnicity, and Muslims in Britain (2005). Modood argues that those who make a case for the right of publication of The Satanic Verses on the grounds of the necessity of allowing free speech simply do not understand the nature of the violence experienced by Muslims when they encounter insults to their prophet.2 Perhaps, more significantly, he wants to claim that the Rushdie affair cannot be addressed by speaking about racism:

“Fight racism, not Rushdie”: the stickers bearing this slogan were worn by many in 1989 who wanted to be on the same side as the Muslims. It was well-meant but betrayed a poverty of understanding. It is a strange idea that when somebody is shot in the leg one says, “Never mind, the pain in the elbow is surely worse.” Why should reference to the real problem of racism lessen religious pain.” (MP, 103)

The consequence of this claim for Modood is profound. He wants to reconceive the ways of thinking about how ethnic minorities inhabit Britain: “in their understanding of race, Muslims are wiser . . . than radical antiracists: in locating oneself in a hostile society one must begin with one’s mode of being, not one’s mode of oppression, for one’s strength flows from one’s mode of being” (MP, 107). Of course, for Modood, the mode of being is Muslim and should not be confused with racial or regional self-understanding. It could be said, then, that what is conceived as hostile is, in fact, produced by the mode of being. The specificity of the injury has to do with the specificity of Muslim self-constitution. Even more so it has to do with forms of devotion particularly strong among South Asian Muslims of rural, peasant background (MP, 106–7). Antiracists simply fail, then, when they demand other forms of political solidarity, or when they subsume Muslim pain to racist anger. Modood is insistent that this mode of veneration of Muhammad is quite distinct to South Asians. In addition, it is important, according to Modood, to remember that, aside from Teheran, the demonstrations were held in Johannesburg, Bradford, Bombay, and Islamabad (MP, 106).

At the same time the social conditions in Britain and India exacerbate the pain (he does not mention Pakistan here):

It was not the exploration of the religious doubt but the lampooning of the Prophet that provoked the anger. This sensitivity has nothing to do with Qur’anic fundamentalism but with South Asian reverence of Muhammad (deemed by many Muslims, including fundamentalists, to be excessive) and cultural insecurity as experienced in Britain and even more profoundly in India. (MP, 106)

So social oppression is important, but it should not be coded in terms borrowed from the racists because of the distinctness of South Asian Muslim immigrant identity. My suggestion that injury is a useful term because of racism would not be quite right according to Modood because it misrecognizes the ontology—the mode of being—that is the source of this Muslim group’s identity. Although Modood does not specify the group, presumably he means to refer to Barelvi attachment to the Prophet. To the extent that this group is denied rights and persecuted, the persecution feeds sensitivity that is already in place because of this very particular form of regionally identified reverence. More than fifteen years later, it is significant that in his response to the Danish cartoons Modood does not emphasize religious pain or a South Asian aspect of a particularly intense form of very personalized religious devotion. He does point out that arguments such as his have become normalized since the publication of The Satanic Verses, as evinced by the fact that many British papers did not reprint the cartoons. It is a normalization in which Modood has played an important role; and, for his contribution, he has been recognized by the British government with an MBE.

Saba Mahmood, too, talks about religious pain in her essay on the Danish political cartoons, although she does not cast the veneration Muslims feel for the Prophet as merely regional. Her discussion of religious pain is reprinted (from Critical Inquiry) in a volume called Is Critique Secular? Blasphemy, Injury and Free Speech, whose contributors include some of the most vociferous critics of secular liberalism on the theoretical scene: Judith Butler, Wendy Brown, and, of course, Talal Asad.3

As is to be expected, Mahmood’s is a more theoretically inclined discussion than Modood’s; it also has a different conceptual prompt. Mahmood was “compelled,” she says, to write the essay because of the “immediate resort to juridical language” by all sides in the controversy (RR, 36). Both defenses of the cartoons and opposition to it “remained rooted in ‘identity politics’ (Western versus Islamic) that privileges the state and the law as the ultimate adjudicator of religious difference.” Mahmood’s project, then, is to “think critically about the ethical and political questions elided in the immediate resort to the law” (RR, 67). Mahmood is insistent that her aim is not to “provide a more authoritative model” for understanding Muslim anger over the cartoons since the motives for the protests were “notoriously heterogenous” and cannot be explained through a “single causal narrative” but instead to “push us to consider why such little thought has been given in academic and public debate to what constitutes moral injury in our secular world today” (RR, 70).

It might not be unfair to say, then, that the object of intellection in the essay is something called a “modern secular order.” More interestingly, to the extent that all current law is modern, it is also secular and liberal. This is evident in Mahmood’s discussion of Hussein Agrama’s analysis of the Abu Zayd trial, in which the Egyptian state incorporated a notion of hisba from classical Sharia but in which the form it took apparently “differed dramatically” in that it came “to be articulated with the concept of public order and the state’s duty to uphold the morals of the society in congruence with the Islamic tradition” (RR, 87). What’s most significant to Mahmood is the “striking resemblance between the Egyptian legal argument and those of the ECtHR” in the case of the Otto-Preminger-Institut versus Austria (RR, 87), where the court upheld the Austrian decision to ban a film offensive to “Christian sensibilities” (RR, 84). In both cases, Mahmood sees the law as upholding majoritarian interests—as she does in the case of the ECtHR decision to uphold a Turkish ban on a book deemed offensive to the majority Muslim population (RR, 87). So Muslims, who resort to the law, simply “remain blind” to the normative disposition of secular-liberal law to majority culture (RR, 88). Since Mahmood does not say so, I do not know if she believes that there is a nonsecular, nonmodern, illiberal juridical tradition that does not privilege the majority or if this is a problem that is constitutive of the law itself. In other words, it’s not clear if there is something in the very process of the codification necessary to law that then simply means that law favors order—emanates perhaps from the need for order—and that order itself can only be maintained by catering to a majority whose cooperation is its necessary adhesive force. On this reading, codification requires normalization and normalization requires social adhesion, which can only be achieved by catering to, perhaps even morally bribing, the majority. In the conceptual terrain in which Mahmood’s argument is articulated an attendant and crucial question is: What precisely is an illiberal state in modernity?

As it stands, it seems as if the interchangeability of secular, modern, and liberal marks the redundancy of secularism as a descriptor. What is really being contested, then, is the structure of actually existing institutions, which by the fact of their currentness are secular. Moreover, all those interchangeable things are also Protestant-Christian “in contour.” If the argument seems a little circular, it does because it is.4

The other side of Mahmood’s argument is the explanation of moral injury, and how Muslims experience it. The argument is motivated as an address to liberal confusion. “Moral injury,” as felt in the Danish cartoon controversy, is something liberals don’t understand, and to them it must be made intelligible. Interestingly enough, the person who is presented as most baffled is Tariq Ali, liberal only in some rather philosophically elastic conceptual universe and increasingly a reluctant proponent of radical Muslim groups, like the Taliban, for their “anti-imperialist” tendencies; in this way the argument accrues and grows, gathering different groups and persons of various affiliations, so it includes progressives, liberals, or anyone who does not get it, yoked together by a puzzled secular orientation. Mahmood’s project is to show a way out of such puzzlement.

The conceptual resources Mahmood draws upon to explain how Muslims experience the moral injury that leads to religious pain come with a peculiar inadvertency. There is a certain care with which Mahmood points out that there were “heterogenous impulses” at play in the controversy and that no “single causal narrative” can explain the events that ensued upon the publication of the cartoons; and yet, despite these cautions and caveats, a figure of a “devout” Muslim is produced in negative contrast to whatever is modern, liberal, secular, Protestant. This contrast, then, stabilizes a notion of a Muslim identity constituted by religious pain and a particular susceptibility to the kind of moral injury sustained in the Danish political cartoon affair. The stabilization occurs as a consequence of Mahmood’s procedure in establishing why the moral injury is unintelligible to the puzzled, and of the way she produces a map of the impasse between liberal confusion and Muslim pain through an account of what she designates a “semiotic ideology.” This semiotic ideology, then, is what separates the two sides in the controversy and makes moral injury unintelligible to those of a secular, liberal disposition.

In order to explain how this ideology functions, and to provide a way of transcending its limitations, Mahmood turns to Webb Keane’s work on Protestant missionaries, W. J. T Mitchell’s notion of images and icons, and Kenneth Parry’s discussion of Aristotelian notions of schesis and their use in the second Byzantine iconoclastic controversy. It is an impressive, even dizzying, marshaling of secondary conceptual resources. Keane’s work on Protestant missionaries enables the insight that there are limits to a Protestant “semiotic ideology,” most clearly evinced by the “shock” experienced by “proselytizing missionaries” on first contact with natives for whom material objects were invested with “divine agency.” These natives apparently considered the exchange of material objects an “ontological extension of themselves.” In the process they managed to dissolve the “distinction between persons and things” (RR, 72). The missionaries’ “dismay” at the “moral consequences” of “native epistemological assumptions” has “resonances with the bafflement many liberals and progressives express at the scope and depth of Muslim reaction over the cartoons today” (RR, 72–73).

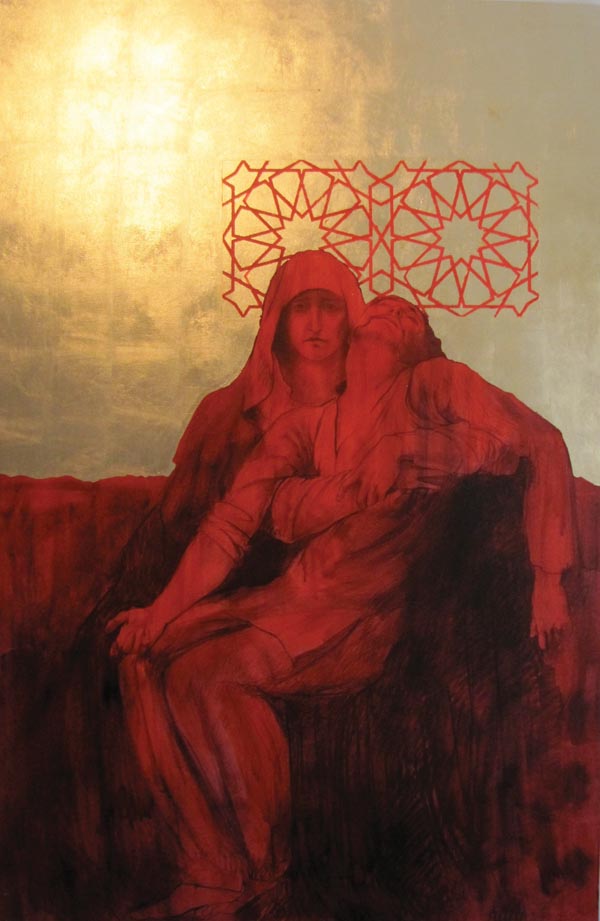

A way out of this confusion is ostensibly offered by Mitchell’s understanding of icons. Mitchell’s insistence that vision is not reducible to “language, or sign, or discourse” and that the field of “visual reciprocity” is constitutive of social reality is of great use to Mahmood (RR, 71). Mahmood’s gloss on this is to suggest that “not all semiotic forms follow the logics of meaning, communication, or representation” (RR, 71). This explains, then, the inability of liberals and missionaries to understand what precisely it is that images do. The point for Mahmood is that “a devout Muslim’s relationship to Muhammad is predicated on an “assimilative” model rather than a “communicative or representative” one (RR, 76). This devout Muslim’s relationship with the Prophet is based not just on following his utterances as collected in the form of the hadith but instead on emulation. In what is essentially an explanation of how Sunnah functions, she describes how “devout Muslims” “try to emulate how he dressed; what he ate; how he spoke to his friends and adversaries; how he slept, and so on” (RR, 75). At this point, an astonishingly sacramental quality creeps into Mahmood’s prose: “These mimetic ways of realizing the Prophet’s behaviour are lived not as commandments but as virtues where one wants to ingest, as it were, the Prophet’s persona into oneself” (RR, 75; italics mine). This is remarkably and significantly in line with discussions of affective piety and traditions of imitatio Christi. The metaphor of “ingestion” seems to derive from a notion of communion, shared by the Eastern and Catholic Churches, except that in this context the transformation it theorizes sets up a bodily merge between Muhammad and devout Muslims, instead of Christ and Christians.

Mahmood’s metaphor also reminds us of the intellectual contexts of the 1980s and 1990s that saw a resurgence of interest in European Catholicism and premodern notions of Christianity. It is this milieu, which must also, I think, be taken into account when the framing of contemporary arguments about religion is being analyzed. Talal Asad’s work is very much part of this intellectual moment. A fundamental conceptual strut of Mahmood’s position is based on an argument Asad popularized in the late 1980s. He suggested it is a modern and thus, on Asad’s terms, necessarily colonially inflected concept of religion that suggests that religion requires belief and assent to a set of propositions. Asad is perhaps one of the major disseminators of a critique of this concept of religion, particularly as it may pertain to misunderstandings of Islam and very much a part of the intellectual context of the fin de siècle of the twentieth century. For Mahmood, one of the reasons liberals and Protestants do not understand native/Muslim (the conflation is slowly consolidated) attachment to images or religious figures is that they are too reliant on this Protestant-modern notion of religion.5 Mahmood’s metaphor of ingestion is the very antinomy of this ostensibly modern notion of religion. Ingestion gives you transmuted being, not discursive belief. But as Mahmood’s metaphor makes clear such a critique of modern religion is itself part of a certain Christian nostalgia that undergirds the contemporary turn to religion, and links it also to another, Modernist, context. The idea of a different, unruptured mode of religious identification, one that overcomes relations between subject and object, thought and feeling is what T. S. Eliot argues for when he laments the “dissociation of sensibility” that ostensibly sets in at the end of the seventeenth century. Once we remember the Modernist context, even the turn to Byzantium seems overdetermined—one has only to think of Yeats.6 As I suggested in the previous chapter, the intellectual formation of which Asad and Mahmood are leading proponents is as much driven by Modernist and Anglo-Catholic anti-Reformation thought as it is by Weberian conceptions of the relation between the rise of Protestantism and the consolidation of the modern capitalist order.

Mahmood supplements the notion of ingestion with Kenneth Parry’s reading of the importance of Aristotelian notions of schesis in Byzantine iconophilia in the second iconoclastic controversy. What this reading of Byzantine Christianity is supposed to offer is a precedent for understanding modes of identification between subject and object of veneration that do not attribute arbitrariness to the attachment between image and deity or native and image/object. A different model of relation along with the metaphor of ingestion allows for completion of a different semiotic ideology—one that can provide a counter to the liberal-Protestant version.

It is particularly the iconophiles’ defense of their doctrine of “consubstantiality” against charges of idolatry that interests Mahmood. The relation between image and deity is one, as she presents it, in her reading of Parry of “homonymy and hypostasis: the image and deity are two in nature and essence but identical in name” (RR, 77). In order to explain this further, Mahmood turns, very briefly, to a historian: “In the words of the historian Marie-José Mondzain, to be the ‘image of’ is to be in a living relation to” (RR, 77). Mahmood’s expansion of this is that schesis “captures this living relation because of its heightened psychophysiological and emotional connotations and its emphasis on familiarity and intimacy as a necessary aspect of the relation” (RR, 77).

What one might expect after this is a discussion of images of Muhammad and their living relation to the Prophet and of the Danish political cartoons as some particularly offensive perversion of such iconographic impulses, since Mahmood has already told us it is not the representation per se in the cartoons that is objectionable—an argument, in any case, that would be hard to sustain given Mahmood’s conceptual recourse to iconophilic rather than iconoclastic thought. But Mahmood has also already set up the meaning of icon as metaphorical and not literal: an icon is not just an image; it can also be “a cluster of meanings” that can suggest “a persona, an authoritative presence, or even a shared imagination” (RR, 74). The icon is thus “a form of relationality that binds the subject to an object or imaginary” (RR, 74).7 In any case, once the icon is established as any sanctified relation between entities, things, or persons, it is perhaps not a complete surprise when Mahmood takes the template of Parry’s discussion of Byzantine uses of schesis to apply to the relation between Muhammad and the Muslim rather than Muhammad and his image. Mahmood begins the paragraph that follows the one about the relation between image and deity with the following sentence, and it is the execution of the shift that intrigues me here: “What interests me in the iconophile tradition is not so much the image as the concept of relationality that binds the subject to the object of veneration” (RR, 77). At this point, it is not at all clear whether the relation in question is between the image and the deity, which is what the preceding sentence is about, or between Muhammad and the believer. What, in other words, is the object of veneration here? Is the relation of image to deity a relation of veneration? Moreover, is image to the Muslim as Muhammad is to the deity? How does one map one relation onto the other without careful elucidation? Is the Muslim, on these terms, the image of Muhammad?

The passage that follows is, in my view, one of the two cruces of the essay, and in it Mahmood begins to attempt to clear the way for what is nothing less than a new theory of Muslim worship. I will quote it at length.

This modality of relationship is operative in a number of traditions of worship and often coexists in some tension with other dominant ideologies of perception and religious practice. The three Abrahamic faiths adopted a range of key Aristotelian and Platonic concepts and practices that were often historically modified to fit the theological and doctrinal requirements of each tradition. In contemporary Islam, these ideas and practices, far from becoming extinct, have been reconfigured under conditions of new perceptual regimes and modes of governance—a reconfiguration that requires serious engagement with the historical relevance of these practices in the present.

Schesis aptly captures not only how a devout Muslims relationship to Muhammad is described in Islamic devotional literature but also how it is lived and practiced in various parts of the Muslim world. (RR, 77)

It is still not clear which modality of relation is at play here, or even before we get to its modality, which relation is at stake here. Is it the relation between image and deity or prophet and follower? Or both, or is it that one can substitute for the other?

The more intriguing line running through this passage is the quiet creation of this mode of Muslim worship as nondominant, and potentially a minority, within Muslim global practice—a minority also within a group of Muslims who start out in the article as the offended minority within Europe. At the same time, Mahmood’s procedure allows for the creation of this mode of worship as potentially representative because it is intended to explain “religious” and “Muslim” pain, not the pain of some Muslims. As Mahmood will argue later in the article, it is in relation to this, not necessarily representative, form of Muslim self-constitution that the “Judeo-Christian sensibilities that undergird secular liberal law” might have to be changed in order to accommodate the Muslim minority in Europe. (I will return to this fascinating moment later.) In this passage, the modes of devotion Mahmood describes in the essay are “new” “reconfigurations” at odds with “dominant” largely unnamed ideologies, and these modes are not confined to European Muslims—the prime players in the controversy. In fact, some of the most important mobilizers in the Danish cartoon affair are not mentioned at all.8 It turns out that these modes of worship are spread through a variety of largely unspecified Muslim contexts—although as a source of evidentiary material, Egypt runs large through the article and its footnotes.

Mahmood is creating a new-old Muslim mode, which names a global polity through a complexly analogical procedure. What Byzantium offers is a precedent for understanding antiliberal/ anti-Protestant modes of identification between subject and object of veneration. The use of Aristotelian notions of relation combined with the metaphor of ingestion allows for the completion of a different semiotic ideology. This counter-ideology could be said to comprise a Catholic-Byzantine mode of thinking as opposed to a Protestant one. An intriguing side effect is a remerging of the Eastern and Catholic Churches through the creation of a Byzanto-Catholic Islam offered in response to modern/liberal/Protestant/secularism, and created through this analogical assembling of a semiotic counter-ideology. There is a reciprocal creation, thus, of a counter-Enlightenment, even Counter-Reformation, mode of European affective, constitutively embodied, thought offered as a mode of antisecular, anti-Protestant, antiliberal religiosity and of a Muslim mode of affective embodied devotion and ethical thinking also offered as a mode of antisecular, antiliberal, anti-Protestant being. These modes of thought and being are both connected through Abrahamic variations on Platonic and Aristotelian thought and illuminated through an assemblage of Catholic-Byzantine concepts.

In addition, what this recourse to Byzantium and ingestion and icon also enables is for Mahmood to assert that to insult the Prophet is to actually hurt a Muslim. In other words, to inflict a pain a Muslim has no choice but to feel, or perhaps only the devout or the nondominant Muslim has no choice but to feel. Those who adhere to the “normative conception of religion as belief” tend to assume that “the epistemological status of religious belief” is “speculative” and thus “less ‘real’” than the materiality of race and biology” (RR, 81). Mahmood aims to reconceptualize the materiality of “religious belief” in order to explain the nature of the injury felt by Muslims. Religious offense is moral injury that causes a pain it would be wrong to see as merely psychic (hence the term psychophysiological) and is in fact akin to racial assault but not entirely reducible to it, yet the pain turns anything perceived as offensive into physiological as well as psychic attack—that the theological premise of such identification itself might be considered idolatrous, and thus hugely suspect, by radical, militant, yet minority (depending on regional and national context), or state-sanctioned or state-complicit branches of Sunni Islam is something that she registers only in her passing invocation of dominant ideologies.9

The form of the analogical procedure here works not only to produce an affinity between colonizing missionaries and present-day liberals and progressives but also to occlude the iconoclasm of many contemporary and historical forms of Islam, including those professed by many of the actors in the Danish cartoon controversy. Would the dismay of the Protestant missionaries have been distinct from that of Muslims encountering Hindu “idols” or Muhammad’s relation with “false gods” in Mecca? What are we to make of the Taliban’s hostility, bafflement, or, for that matter, affective response to the Bamiyan statues or the Saudi establishment’s hostility to the pilgrims who look for graves of revered figures from the Muslim past in Mecca and Medina, an act that is considered idolatrous by the establishment. In other words, who is akin to the missionary here, and how many degrees of separation does that confer from the liberals? What of the desecration of Muhammad’s gravestone by the Wahhabis as far back as 1804?10 What also of those who today blow up Sufi shrines, or attack Shia Ta’aziyeh processions? Can liberal “bafflement” be shamed into understanding by an embarrassing, or worse, genealogical association? Can, in turn, such a procedure externalize a notion of an iconoclastic “semiotic ideology”—shared by segments of modern and early Islam and, equally, resisted and transformed by other segments—as somehow only an arid symptom of a liberalism or modernity or secularism, or all of the above (at this point I am simply not sure what to call it), Protestant-Christian in its contours? In other words, can an Islam conceived in Byzantine-Catholic terms, stabilized by opposition to liberal, Protestant, secular modernity, do away with some of the most intense and consequent divisions, precisely over icons and iconic attitudes, in a range of diasporic and Muslim-majority contexts today?11 As we shall see in the next chapter, the use of aesthetic iconic traditions from Catholicism and Byzantium is instead being used to contest neo-orthodox Islamism, which is frequently perceived to have radically iconoclastic impulses. A more interesting question might be: How does a presumptively Barelvi notion of Islam—referred to by Modood in the context of The Satanic Verses—merge with Wahhabist, Salafist, and perhaps even Deobandi strands in the metropolitan context, and how are the Wahhabi influence and colonial context of Deobandism forgotten? In other words, it might be worth pausing over how the historical affinities and differences are reswirled into just “Islam” in the metropole.

If the production of this countersemiotics is to enable better, and equal, coexistence across lines of “religious difference” it raises a host of difficulties. The “devout Muslim” produced through an analysis of his or her “religious pain” is one who feels an injury unintelligible to liberal, modern, Protestant seculars, shares a relation to icons and iconic objects and imaginaries that are akin to, and even share, Byzantine-Aristotelian notions of the icon, manifests a late-twentieth-century semiotic theory advanced by Mitchell and an epistemology (held by tribal natives) akin to that which confused early Protestant missionaries. But this Muslim then gets to stand in as representative for Muslims in general, and his or her pain is invited to begin to set guidelines for how Europe should learn to deal with its migrants.

In the second of, what I think of as, the two cruces of this essay, Mahmood brings together the antilegalism of her critique of secular modernity and the consequences of her explication of moral injury and Muslim pain. She argues, as against positions advocated by Modood, that Muslims who turn to the court or to the state simply do not understand that to turn this kind of injury into a legally prosecutable crime is to fundamentally transform or destroy that very “religiosity.” Given its predication on entirely different conceptions of the “subject religiosity, harm and semiosis” to turn it over to the “logic of civil law is to promulgate its demise (rather than to protect it)” (RR, 88). This leads, then, to what is either the bold naming of an impasse or the equally bold, though implicit, suggesting of a solution:

Ultimately, the future of the Muslim minority in Europe depends not so much on how secular-liberal protocols of free speech might be expanded to accommodate its concerns as on a larger transformation of the cultural and ethical sensibilities of the Judeo-Christian population that undergird the cultural practices of secular-liberal law. (RR, 89)

Since secular-liberal law, even when it upholds Muslim majoritarian interests (as in the ECtHR decision in the case of Turkey), is Judeo-Christian at the level of “cultural and ethical sensibility,” it will, in fact, transform Muslim religiosity. I am not interested here in disagreeing with Mahmood on the efficacy, let alone ethics or politics, of turning to the law to impose various forms of censorship; I am interested in trying to understand what, if anything, is being advocated. Since Muslims apparently share some sensibilities with Jews and Christians, which sensibilities would require transformation on the terms of the essay? Should Jews and Christians become less Jewish and Christian? Should Christians become iconophilic affiliates of the Eastern Church or more Catholic? What are Jews to do? Is it instead that the underpinnings of the law need to become more Eastern Christian/Catholic and thus potentially more Muslim? Since it is the shared, if refracted, Aristotelian and Platonic strands of thought that run through the Abrahamic religions which are used to explain Muslim practice, it is not clear whether law has to become less Judeo-Christian or more in line with the kind of Islam in line with aspects of law assumed to be more consonant with anti-Protestant strains of Christianity.

The problem manifest here runs through the essay. When I try to describe Mahmood’s analogical procedure, I am not at all suggesting that it is comparison per se that ought not be undertaken. Neither do I wish to deny similarities and continuities between the three religions. Of course, there are shared philosophical traditions and theological impulses in the three Abrahamic religions, and to the extent that both Asad and Mahmood are attentive to these, the turn to religion of which they are part is intellectually useful. But my intention is rather to question the way in which Mahmood’s procedure covers divisions within societies and turns them into historical monoliths, which so conceptualized are then made to do analogical work that, in turn, occludes consequent divisions and the complexity of political formations in the present. A procedure that shows the contestations that attend repeated divisions over icons and iconoclastic thought in Byzantine and Western Christian societies—the iconoclastic controversies and post-Reformation struggles—that shows how similar divisions are lived in Muslim contexts, and how they might be reproduced through contact and emulation in different Islamicate societies and diasporic contexts, is very different from a procedure that uses anticolonial and anti-imperial sentiment in order to stabilize (and create) monolithic identities even while parenthetically disavowing such monolithicism.

Moreover, my point is not at all to question Mahmood’s skepticism about enshrining anti-Protestant religious impulses into civil law (which she has also suggested is immanently Protestant), or to question her mention, in passing, of the problem of the nation-state as it cross-cuts the issue of minorities. Indeed, once one shifts locations, critiques of the entwinement between religious concepts and law, foregroundings of the problem of the nation-state’s relationship with minorities—especially as it intersects with colonial history, postcolonial crisis, and a newly explicit imperialism—acquire crucial though very different, if connected, valences. It is to these that I would now like to turn.

Regimes of Feeling

In the context of Pakistan, the question of the relationship between minority, identity, and law gets at the very heart of the problematic of the postcolonial nation-state. The battle around what is called the “blasphemy law,” although the word “blasphemy” does not occur in it, confronts us with the most challenging questions that comprise the predicament of the postcolonial state: how are institutions to be formed or re-formed in the context of decolonization? How are the configurations of law and sensibility within structures of colonialism to be rethought, or even undone? In the age of renewed religious nationalism, how are we to configure, or for that matter even recognize, what is indigenous? How is religious indigeneity to be secured? What is its relation with religious orthodoxy?

Postcolonial critics and theorists of South Asia have tended to focus on the Indian state’s relation with religion and religious minorities. From this perspective it is the avowedly secular state’s failure to incorporate religious minorities, while honoring their difference, that marks the limit or failure of secularization. According to Gauri Viswanathan’s subtle and inflected account of belief and conversion in modernity, secularization in India has always been a “fraught process,” in large part because parliamentary reform has not been able to absorb religious minorities as “citizens.”12 For Viswanathan this is because, in India, state formation is “basically incorporation of the subjects into a colonial state”; after independence this process transforms into absorption into a “hegemonic state in which the social relations sanctioned by colonialism continue virtually uninterrupted.”13 The continuities between the colonial and postcolonial state are important. Equally important, however, is that religious conflicts in South Asia seem also to have intensified in ways that reveal the reconfigurations of power in the post-Independence states. In the Indian context the destruction of the Babri mosque and the violence in Gujrat may be the most extreme signatures of this intensification. These postcolonial reconfigurations invite more sustained study of majoritarian action, agency, and responsibility within the not quite new nation-states.

The postcolonial state’s combination of rupture and continuity with the colonial state requires more work on what the postcolonial state has added to these social relations, and the global, Cold War context of these additions. In Pakistan, the Sunni Muslim majority has come increasingly to define the denominational inflection of the state; and the marginalization of minorities as citizens does not emanate from the failure of state-sponsored secularization to ensure “absorption.” It issues instead from attempts to secure the religious underpinning of the postcolonial state, under conditions of the large-scale, Cold War–enabled decimation and neutralization of progressives opposed to these attempts, combined with the addition of the sensibilities of a specific religion to penal laws designed to manage colonial populations by letting them have their religion. Increasingly, it is a state with a particular Islamic inflection that deprives minorities of their status as citizens, sometimes because it is attempting to secure a particular meaning of Islam and to create a proper Muslim persona—by way of the control of the image of the Prophet—in and through the structures of the state. The most powerful instrument of this consolidation has been a military government’s addition of a series of amendments to British penal law. The centrality of the military’s shaping of state structures itself invites a more sustained conceptualization of the praetorian element in structures of governmentality than is possible here. The peculiar combinatory of normalization through the juridical sphere of the law and the sovereign power of the military in the process of promulgating the law throws up a paradox, for it suggests the normalization of the exceptional. The military’s relationship to the National Assembly during the Zia period, and more generally over the national history, suggests the ongoing necessity of conceptualizing the role of structures of state, including militaristic ones, in the formation of the juridical sphere.

Viswanathan has been critical of the reduction of religion to “wounded sentiments” in the Rushdie affair and has, in my view, rightly seen a recourse to the language of the wound as a “permissible secular gesture” that has the virtue of not “pandering to religious absolutism” on which these sentiments are based.14 Such a privileging of “the subjectivity of sentiment over the objectivity of creed steers clear of antiheretical presumptions while still holding fast to the ideal of cultural relativism.”15 It is not incompatible with Viswanathan’s argument to emphasize that, in the Anglophone context, the language of the wound, when invoked in relation to the religions of South Asian former subject populations, issues from colonial law, shaped in turn by the need to produce a governable population.

It is, of course, not surprising to say that the protection afforded the religious feelings of the colonial subject is entangled with the need to produce a more governable polity and that such governance was assumed to require managing relations between the different religious populations of the Indian subcontinent. As far back as 1785, in his oft-quoted preface to Charles Wilkin’s translation of the Bhagavad Gita, drawing upon the idiom of English sentimentalism, Warren Hastings connected the “conciliation” of “distant affections” with the “exercise of dominion.” The mode of this conciliation was the gathering and dissemination of local knowledge; it was indeed in the guise of what one might characterize as a certain “respect” for indigenous religious knowledge that the consolidation of colonialism was to occur:

Every accumulation of knowledge and especially such as is obtained by social communication with people over whom we exercise a dominion founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state: it is the gain of humanity: in the specific instance which I have stated, it attracts and conciliates distant affections; it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjection; and it imprints on the heart of our own countrymen the sense and obligation of benevolence.16

What is often emphasized in the discussion of colonial law is the production of knowledge and its relation with colonial conquest.17 A more systematic understanding of the colonial production of religious affect and its imbrication with the institutions of religious knowledge, “custom,” and code is also required. The relation between sentiment and subjection would underpin an emphasis on indigenous law and custom, and this foundational entanglement of affect and the consolidation of conquest was to prove extraordinarily consequential in the codification of Hinduism and Islam in India. The explicit entanglement of knowledge, the “right of conquest,” and the need to find a way to win over the affections of the people in Hastings’s introduction is remarkable. The production of such conciliating knowledge is also part of the project of a creation of a fiction of reciprocity in the figure of colonial “benevolence” to be imprinted on the “heart” of the English. This benevolence is to be fortified by the “virtue” rather than the “ability” of the employees of the East India Company, for it is on this virtue that the Company must rely for the “permanency of their [sic] dominion.”18 English virtue and the conciliation of native affection are to remain forever connected. Bernard Cohn has made the case that Hastings invented the emblematic figure of British imperialism, the colonial administrator who knows the natives.19 One might add that the political use and efficacy of this figure lies in his anthropological knowledge of native difference, a knowledge undergirded by a blend of benevolence, virtue, conciliation, and domination. The anthropological administrator thus invented is a sentimental figure.

That this sentimental idiom would explode into Burke’s sensational rhetoric, which was attended by visions of abject Indian suffering and famously of female bodies, wrenched from homes made sanctuaries by religion, so brilliantly discussed in Sara Suleri’s seminal essay on the impeachment of Warren Hastings, is a symptom of the ubiquity of the idiom in the formation of “imperial sensibilities,” even in their ostensibly critical guise.20

The law configures the subject population as a body to be engaged and humored (“conciliated” one might say) at the level of feeling; that is, it produces an understanding of the native’s relation with religion as a series of affects, a mesh of feelings rather than principled commitments or propositions, even as the knowledge produced in colonial institutions fixes and codifies religious practice and belief. On the terms of the colonial state, it is these feelings that required protective governance; the penal code is to assist in the management of the realm of native emotion. Conquest and plunder were to be followed by conciliation.

It is perhaps unsurprising that the first draft of the code was authored by a law commission chaired by Thomas Macaulay in 1837.21Sentimentalism and liberalism converged in the juridical sphere of the colony, shaping the discourses of law and knowledge, creating religious affect as a mesh of relations of power—of the colonizer to dispense the salve and of the colonized to demand and exercise power by avowing religious feeling—and, in the postcolonial aftermath, enabling the discursive power of the praetorian state under Zia-ul-Haq, whose addition of five amendments to the British colonial code is central to the state’s attempted capture of its citizens’ Muslim persona—indeed, to its creation of an affective sphere in which every citizen is required to develop a relation of feeling to the icons of Islam chosen by the state.

Of the four articles in the chapter (XV) pertaining to “Offences Against Religion” in the Indian Penal Code of 1860, two explicitly invoke religious feelings. In article 297, the object is to protect “funeral ceremonies,” places of burial, potential desecrations of the dead from people who have “the intention of wounding the religious feelings of any person, or of insulting the religion of any person, or with the knowledge that the feelings of any person are likely to be wounded, or that the religion of any person is likely to be insulted thereby, commits any trespass” in any place that might be associated with burial or funeral ceremonies.22

In article 298 the solicitude for the religious feelings of the colonized is more central to the juridical aim:

Uttering words, &c., with deliberate intent to wound the religious feelings of any person.

Whoever, with the deliberate intention of wounding the religious feelings of any person utters, any word or makes any sound in the hearing of that person, or makes any gesture in the sight of that person, or places any object in the sight of the person, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine, or with both. (IPC, 139)

The only amendment added by the colonial government (295–A) in 1927 was in response to the conflict that ensued upon the publication of the pamphlet, Rangīlā Rasūl (The Libertine Prophet), when the article most explicitly committed to containing communal public disorder was deemed inadequate to convict the author of the text.23

The original article 295 reads as follows:

Injuring or defiling a place of worship, with intent to insult the religion of any class:

Whoever destroys, damages or defiles any place of worship, or any object held sacred by any class of persons with the intention of thereby insulting the religion of any class of persons, or with the knowledge that any class of persons is likely to consider such destruction, damage or defilement as an insult to their religion shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both. (IPC, 138)

Amendment 295-A adds outraging “religious feelings” back into the article where in the original article the crime is “intent to insult.” Perhaps most significantly, it links these feelings to religious “beliefs.” In the Pakistan Penal Code, the substitution of “the citizens of Pakistan” for “His Majesty’s subjects” for those whose religious feelings need to be protected establishes it as the most ecumenical of the amendments, for, unlike the post-Independence amendments, it configures those who can be injured as Pakistani and not only Muslim:

Deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs:

Whoever with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of the citizens of Pakistan, by words, either spoken or written or by visible representations insults the religion or the religious beliefs of that class, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, or with fine, or with both. (PPC).

Reading the language of the colonial code helps dispel a certain confusion that might have been felt around the Rushdie affair, the rhetorical field of which comes increasingly to seem like part of the long afterlife of colonial law. At the time, commentators, such as Roald Dahl, critical of Rushdie, were prone to say that Rushdie “knew” what he was doing. One might have wondered: What is it that he should have known? What was the stake of such knowledge? Why, in an age that was otherwise so comfortable with the unconscious prompts of speech, action, or writing, was knowing so important? Article 295 clarifies the genealogy of that use: in the article, the punishment is for anyone who acts “with the knowledge that any class of persons is likely to consider such destruction, damage or defilement as an insult to their religion.” Article 295-A adds the written text to the list of injury-causing objects. It becomes clear that knowing as conscious knowledge, as that which should have activated a prohibition within himself that would have negated Rushdie’s writing of the novel, is related to the legal requirement of “intention” that, in these articles, attends prosecution. “Knowing” in this context suggests a normalization of the law, the linguistic adaptation of the juridical aim of containing trangression and keeping social order while managing unruly subject populations. “Knowing” also relies on an assumption that as a former “native,” Rushdie has particular access to the feelings of his people and is thus particularly culpable. This proximity then ensures his status as traitor.

Lingering access to the language of the law, shaped by complex processes of historical diffusion, feeds into contemporary British policies of official multiculturalism that seek to turn the management of Britain’s racially different populations over to religious community leaders, and into also the recourse to the notion of religious pain by a proponent of state-sponsored multiculturalism such as Modood, which then is explained in its “Muslim” variation, almost two decades later, by a Foucault-inspired critic of legalism such as Mahmood.24

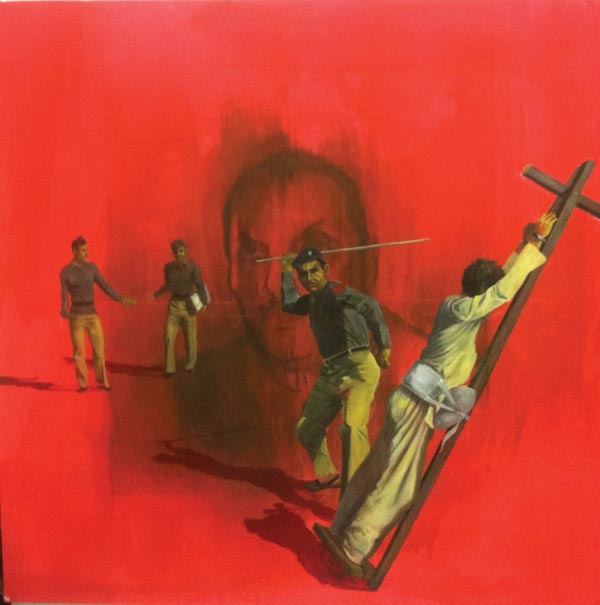

After Independence, the colonial laws come to play a complex role in securing the identity of the nation as Muslim. In their current form, the Pakistani laws regarding offenses against religion, consisting of five amendments added under the military dictator General Zia-ul Haq and the original articles and one amendment of chapter XV of the colonial code, represent an attempt to fill in a particular Islamic content to the religious feelings mentioned in the original code. They do not represent an erasure of colonial liberalism’s protection of the natives from religious pain, simply its attachment to a particular group. The praetorian state attempts the creation of the proper Muslim persona and its relation to Muhammad through military-executive fiat, that is, through the militarized sovereignty of the state, through, in effect, the militarized control and production of iconography and of the citizen’s relations with icons and iconic objects. Perhaps the amendments that do so most explicitly are the ones pertaining to the Prophet and his family:

295-C: Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine. (PPC)

The first amendment to 298—the article originally most directly concerned with protecting religious feelings from being wounded—specified that those who are not to be insulted include the family, the caliphs (in a clause that seems intended to target Shias who tend to be critical of the first three caliphs), and the friends of the Prophet, using the same language of implication and innuendo: “Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred names of any wife (Ummul Mumineen), or members of the family (Ahle-bait), of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), or any of the righteous Caliphs (Khulafa-e-Rashideen) or companions (Sahaaba) of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him)” (PPC). The punishment is imprisonment of up to three years, a fine, or both.

It is 295-C that is usually referred to as the “blasphemy law,” when the term is used in the singular, and one might argue that it represents an attempt to give full juridical force to attachments to Muhammad. The ones that also incurred life imprisonment (295-B and 295-C) and, in the case of insults to Muhammad (295-C), now the death penalty, are used disproportionately in accusation against Christians. The vagueness of its language makes it a particularly useful weapon in the hands of those seeking to settle petty disputes.25 The mandatory death sentence, added under Nawaz Sharif’s first government, suggests that it is this very vagueness of “Imputation, insinuation, and innuendo, directly or indirectly,” that requires the punishment of death in the framing of the amendment, as if the ephemerality of the accusation demands the ultimate corporeal finality for its complete and proper embodiment, perhaps even its reality—as if only the death of the accused can secure the truth of the accusation.26 The refraction of the spirit of the law in the social imaginary is represented by the fact that although none of the accused have been executed by the state, many have been murdered during trial or on release. The addition of the two amendments to the one added after the Rangīlā Rasūl controversy reveals a haunting of the Pakistani imaginary by a colonial history of religious strife, a trauma endlessly to be replayed on the bodies of the nation’s minorities. The minority’s identity as citizen is erased through the production of the citizen’s proper relation with the icon.

A constitutional amendment, which is a crucial precursor to the additions to the penal code attacked the Ahmaddiyya minority through an act of theological targeting.27 Thus when Zia embarked on his process of Islamization, and instituted the changes to the penal code, which was an attempt to reconstitute every aspect of Pakistani society, the space for those legally declared minorities, the Christians, Ahmadis, Parsis, Sikhs, and Hindus, had already shrunk significantly. The space for minorities began to be whittled away with the passing of the Objectives resolution of the Constituent Assembly of 1949, with its emphasis on Islam as the grounds of the state.28 Subsequent negotiations over the question of the sovereignty of Islam in the state in the three constitutions of 1956, 1962, and 1973 further normalized the marginality of minoritarian citizenship.

In the amendment, Ahmadis are defined as non-Muslim through theological targeting. The amendment devolves on the proposition that Muhammad is the last prophet. The doctrinal name for this proposition is Khatm-e nubūwwat (the finality of prophethood), evident in the third part of the amendment:

3- Amendment of article 260 of the Constitution.

In the constitution, in article 260, after clause (2) the following new clause shall be added, namely—A person who does not believe in the absolute and unqualified finality of The Prophethood of Muhammad (Peace be upon him), the last of the Prophets or claims to be a Prophet, in any sense of the word or of any description whatsoever, after Muhammad (Peace be upon him), or recognizes such a claimant as a Prophet or religious reformer, is not a Muslim for the purposes of the Constitution or law.29

The density of Ahmadi belief, practice, and theology has been reduced, by those opposed to the Ahmadis, to what is presented as one theological essential. The Ahmadi belief that their leader, though subordinate to Muhammad, received a revelation is placed against their self-understanding as Muslims, and the finality of Prophethood is invoked to declare them non-Muslims.30 The offense and injury, caused by perceived or actual challenges to the finality of prophethood, are modes of expressing a passionate attachment to the Prophet. They now haunt the national imagination and are a cause of considerable anxiety and fear for Ahmadis and Christians.31

As if performing the centrality of the Ahmadi question to the project of the nation-state, two of the five penal amendments are constructed to target and exclude a particular religious group, the Ahmadis, from the Muslim religious fold and manifest a rather sustained attempt to manage attachments to the Prophet, disallowing those excluded from any attachment or affiliation to him and arrogating to the state the power to curtail its forms and representations. The detail is exhausting, but the amendments are worth reading in full. The sheer length of the articles and the compulsive list of prohibitions emphasize the centrality of the Ahmadi question to the enterprise of securing the content of the Islam forming the ground of the state. The detail suggests, moreover, a will to power that requires the complete eradication of the grounds of the perceived enemy’s religious being. It is not the privatization of belief and practice but its complete confiscation that is at work:

298–B: Misuse of epithets, descriptions and titles, etc., reserved for certain holy personages or places: (1) Any person of the Quadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’ or by any other name) who by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation- (a) refers to or addresses, any person, other than a Caliph or companion of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ameer-ul-Mumineen”, “Khalifatul-Mumineen”, “Khalifa-tul-Muslimeen”, “Sahaabi” or “Razi Allah Anho”; (b) refers to, or addresses, any person, other than a wife of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ummul-Mumineen”; (c) refers to, or addresses, any person, other than a member of the family “Ahle-bait” of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ahle-bait”; or (d) refers to, or names, or calls, his place of worship a “Masjid”; shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine. (2) Any person of the Qaudiani group or Lahori group (who call themselves “Ahmadis” or by any other name) who by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation refers to the mode or form of call to prayers followed by his faith as “Azan”, or recites Azan as used by the Muslims, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine. (PPC)

298–C: Person of Quadiani group, etc., calling himself a Muslim or preaching or propagating his faith: Any person of the Quadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’ or by any other name), who directly or indirectly, poses himself as a Muslim, or calls, or refers to, his faith as Islam, or preaches or propagates his faith, or invites others to accept his faith, by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or in any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine. (PPC)

Promulgated in what was called Ordinance XX in 1984, the attachment of these amendments regarding Ahmadis to the article most concerned with protecting the religious feelings of various groups suggests that the very act of being an Ahmadi inflicts a wound on Muslims, that any claim to being Muslims by Ahmadis is a cause of Muslim religious pain. When I first drafted the preceding sentence, I was responding merely to what I saw as the rhetorical logic of the framing of the amendments, but since then I have discovered that this equation has a diffuse social circulation. In 2010, Nawaz Sharif, announcing his sympathy for Ahmadis following suicide bombings of two mosques, in which eighty were killed, called them “brothers and sisters.” There was condemnation from many clerics for his declaration of such kinship. From across the border in India, the Ahrars, a militant group formed in 1929, ferociously opposed to the Ahmadis, apparently insufficiently occupied with the discrimination against Muslims there, found time to respond. Their leading cleric declared that Nawaz Sharif had “hurt the sentiments of Muslims” by calling the Ahmadis brothers. Showing a blissful lack of anxiety about mediatic representation, they provided this information through an article from the Hindustan Times prominently displayed on their website. The news functions as a mode of self-declaration, indeed, as a form of promulgation.32

At stake is a precise conception of Muslim interiority and an attendant assumption regarding its transparency to the state. The gauge of the authenticity of Muslim interiority is thus a commitment to a doctrinal proposition. On the one hand, the amendments seem to privilege an orthopractic understanding of religion, and Islam, whereby even engaging in a practice is a way of usurping its identity; on the other hand, by their very commitment to the doctrine of the finality of prophethood, they insist that such a practice is dependent on a content assigned to belief—that is, a theological claim with propositional content that requires assent.33 The amendments encode the attempt to strip any possible expression—in practice or utterance—of being Muslims from Ahmadis and thus to take away their very identity. The requirement that Ahmadis have to be prevented from “posing” as Muslims is a complete denial of the ontological possibility of them being Muslim; that is, they can only impersonate Muslims.34 While impersonation is the only action possible by Ahmadis it can turn Muslims away from being Muslim because it invites others, through proselytization and presumably the seduction of emulation, to engage in similar posing. It is this apparent impersonation that then has to be prevented by stripping language from them. Even as the very language of devotion is taken away, they are the ones construed as inflicting the injury.

The genealogy of the word posing in the anti-Ahmaddiyya amendments both demands an attention to the question of belief’s content and illustrates with particular trenchancy the problem of the transformation of minority and nationalism over the course of decolonization. “Posing” comes directly from Abul Ala Mawdudi’s English-language version of the 1953 polemic, “The Qadiani Problem.”35 The pamphlet was written to demand the removal of Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, the foreign minister at the time and the author of the Pakistan Resolution:

But Qadianis penetrate into the Muslim Society posing as Muslims; they propagate their views in the name of Islam; start controversies everywhere, carry on proselytizing propaganda in an aggressive manner and continuously strive to swell their numbers at the expense of Muslim society. They have thus become a permanent disintegrating force amongst Muslims. How can it, therefore, be possible to show the same kind of toleration towards them as is shown towards other passive sects?36

Mawdudi appended two documents by Muhammad Iqbal to authorize this sense of a threat to Muslim society from the group: a letter to The Statesman, which had published Iqbal’s original, 1934 pamphlet against the Ahmadiyya (“Qadianis and Orthodox Muslims”) and a response to Nehru (“Islam and Ahmadism,” also published as “Reply to Questions raised by Pundit Nehru”) who had asked why Iqbal had felt the need to write the first piece, published in 1935. Although Iqbal’s complete oeuvre is more aesthetically and philosophically complicated than these essays suggest, and can even be taken to authorize certain notions of Muslim selfhood and dignity, one might speculate that it is a complex double pressure that leads to this very dark contribution to the status of minorities.37 The first lies in the necessity of an unruptured Muslim identity. The second is in the effect of English on the position he articulates. He produces these statements in Anglophone texts, Mawdudi circulates them in English as well as Urdu, and the law itself is in English. In this Anglophone context, Islam becomes subject to a defensive language of differentiation and becomes permeated by the exigencies of power in the colonial state. Paradoxically in the postcolonial context the Anglophone frame is crucial to the violence of the law, whose defenders repeatedly cast it in anti-Western and anticolonial terms—in terms, in other words, entirely determined by a “Western” audience. The genealogy of the law reminds us that the colonial administration was the first audience to whom Iqbal addressed his demands.

It must be said that, in these essays, Iqbal’s fear is not of secularism or of religion’s expulsion from the modern world but of more, other, religions. In “Qadianism and Orthodox Muslims,” he presents both Bahaism and Ahmadism as instances of pre-Islamic Magianism, which, according to Iqbal, relies on a “constant expectation” of prophets because continuity of prophethood is necessary in the Magian context (QM, 92). The result of the “Magian attitude” is the “disintegration of old communities and the constant formation of new ones by all sorts of religious adventurers” (QM, 92). The return to the pre-Islamic past in such practices entails permanent communitarian revolution and ensures the possibility of new religions. For Iqbal, “since Islam . . . claims to weld all the various communities of the world into one single community” it cannot “reconcile itself with a movement which threatens its present solidarity and promises of further rifts in human society” (QM, 92). What makes Ahmadis so threatening to this solidarity is the challenge they pose to the Muslim community because “the integrity of Muslim society is secured by the Finality of Prophethood alone” (QM, 92). Because Ahmadis claim to be Muslim and engage in practices that are associated with Muslims they undermine the community from within; they are, in other words, internal threats that very locally undermine the vision of global homogeneity—the world as one single community—that constitutes Iqbal’s utopia in these essays.

Ayesha Jalal has argued that within Iqbal’s thought the insistent opposition to Ahmadis issues from the effects of the internal politics of the Punjab.38 On my view, that regional issue intersects with a very precise conception of interiority and a theological intimacy, which shapes the intensity of the disavowal and makes it so necessary to ensure that the “externals” of practice be shown to be at odds with Ahmadi inwardness, that Ahmadis be shown only to be capable of posing as Muslims, since “Qadianism” “retains some of the more important externals of Islam with an inwardness wholly inimical of the spirit and aspirations of Islam” (QM, 93). This denial of the possibility of inwardness is predicated on the importance of the proposition of prophetic finality to Muslim interiority.39 For Iqbal, Ahmadis can only appear to be Muslims because their belief puts them at odds with Islam, and thus their practice must be empty: they cannot possess, what is to Iqbal, a specifically Muslim interiority. Their very intimate challenge comes from their ability to seem Muslim in practice and even in utterance.

The problem of appearing Muslim then becomes a crucial challenge to what Iqbal calls “the parent community” (QM, 96). For this, he says bitterly, figuring colonial adjudication as “care,” “the liberal state does not care a fig” (QM, 95). It is the religious proximity of Ahmadis that makes them so much of a threat despite their very small number. “Parent community” figures religious heresy and theological difference as a disruptive child, and as a child, moreover, with the potential to take over, devouring the parents as it grows up. This figuration is an effect of what Mufti has identified as the “mapping” of the Indian Muslim ashraf “ideology of familial descent” from non-Indic sources on to “the political community or qaum” as a whole during the process of the “nationalization of society.”40 An ideology of familial descent produces a notion of the community as family—a rather tight-knit one, if Iqbal’s rage is to be comprehended. Within this configuration, Iqbal’s constitution of the Ahmadi threat is a way of ensuring that the Muslim community, imagined in kinship terms, remains intact. Iqbal’s dismissal of Mirza Gulam Ahmed as “an Indian prophet,” as opposed to the true Arab one, is rhetorically and politically continuous with the claim to non-Indic roots.

As Jalal suggests, Iqbal’s involvement with the militant group, the Ahrars, is significant, as is the fact that, as she sardonically suggests, “basing Islam’s much-vaunted unity in difference on the logic of internal exclusion was a novel invention for which Punjab’s urban middle-class leadership can rightfully claim credit.”41 But I would emphasize that this local entanglement and its relationship with anticolonial struggle, through the Ahrar’s desire to be more central in the politics around Kashmiri liberation, to which they felt marginal, and to which marginality they reacted with an attack on the All-India Kashmir council when an Ahmadi was appointed president, is articulated through a theological position.42 That the Ahrars went on to fight with Shias in Lucknow suggests that the question of policing the boundaries of theological orthodoxy powers the intensity of the opposition.43 It is, moreover, this theological claim that allows for the subsequent globalization of Ahmadi persecution.

The regnant theories of religion have tended to play down the propositional content of belief.44 Such underplaying issues in part from a contemporary interest in embodiment and practice, but, as Viswanathan has suggested, engaging questions of heresy, blasphemy, and apostasy requires that belief’s content also be recognized. For Iqbal, it was certainly important in these essays, and that importance has proved historically consequential. He is even more clear and insistent about the propositional importance of the finality of the prophethood in “Islam and Ahmadism,” his response to the baffled questions Nehru posed in “The Solidarity of Islam.”45“This simple faith” is, for Iqbal, based on two propositions (RQ, 115). One is, of course, the doctrine of finality; the other is that “God is One” (RQ, 115). “The solidarity of Islam . . . consists in a uniform belief in the two structural principles of Islam, supplemented by the five well-known ‘practices of the faith’” (RQ, 137). It is a similar commitment to doctrine and to keeping practice free of “heretical” innovation that motivates Mawdudi and the framers of the amendment.

Any political engagement with the status of religion has to confront what is to be done (or not done) when a belief is assumed to have been compromised. Framing the question of secularism as a problem of religious sentiment versus free speech, where free speech is assumed to be free secular speech and thus an expression of a hegemonic liberalism opposed to the religious other, simply deflects attention from the conceptual stakes and underpinnings of the political status of belief. It is not surprising then that one of the primary modes of this deflection has been a displacement of the problem onto artistic expression, the valuation of which is, in turn, figured as a residue of the aggressive Enlightenment valuation of man. It is perhaps equally unsurprising that Rushdie has become central to this deflection.

Iqbal’s defense of the practice of the clerical designation of kufr (which he translates, strangely, as “heresy”)—in cases of “minor theological points of difference as well as extreme cases of heresy” against “present day educated Muslims” who deplore the practice—sits oddly with his charge that Ahmadis should only expect to be treated badly as they declare everyone kāfirs (nonbelievers). On his own view, that practice might be construed as an extension of an orthodox habit. Yet, arguing in some sense against himself, he is insistent that these present-day, educated Muslims are wrong to see the practice as a sign of the “social and political disintegration of the Muslim community” (RQ, 116). For the “history of Muslim theology shows that the mutual accusations of heresy for minor points of difference has so far from working as a disruptive force, actually given impetus to synthetic theological thought” (RQ, 116). Declaring each other “outside the fold” ensures intellectual movement and becomes an engine (providing “impetus”) of a project conceived, inconsistently, in Hegelian terms of attaining theological “synthesis.” What, one might wonder, would be the antithesis?

Iqbal, one need hardly point out, is not a traditionalist. He celebrates reformers from Wahhab to Al-Afghani and attacks, in bullet point form, and, in this order: “Mullahism,” “mysticism,” and “Muslim kings” (RQ, 128–29). But for him acceptable designations of other people’s heresy are those that ensure that the Muslim community stays itself, especially since Western colonialism has so endangered it. The problem is one of limits to community, what must be excluded, and to imagination, to the structures of thought, language, filiation, and affiliation that enable the self-policing, or ongoing self-creation, of that limit. In the sustenance and clarification of that limit the Ahmadis seem to play a crucial role in this late stage in Iqbal’s thought.

For Iqbal, political humiliation and the embattled condition of Muslims worldwide is combined with the problem of Muslim minority in India, and it is this connection that allows him recourse both to an analogy with the German state that arose after the defeat by Napoleon at Jena and to Jews in seventeenth-century Amsterdam.46 The separation of Ahmadis from the Muslim majority that he wants the colonial government to institute is justified by an invocation of Spinoza: “Situated as the Jews were—a minority community in Amsterdam—they were justified in regarding Spinoza as a disintegrating factor threatening the dissolution of their community” (RQ, 112). Mawdudi’s “disintegrating force” in The Qadiani Problem is, of course, a slight modification of Iqbal’s “disintegrating factor.” Iqbal is careful to distinguish the leader of the Ahmadis from Spinoza—there is apparently no comparison of intellect between Mirza Ghulam Ahmed and the philosopher (RQ, 111); and, moreover, the Ahmadis are a bigger threat (RQ, 112). The example clarifies what is acceptable in order to ensure the cohesiveness of the community. Expulsion from the group—disinheritance—is an acceptable price for solidarity: “Politically, then, the solidarity of Islam is shaken only when Muslim states war on one another; religiously, it is shaken only when Muslims rebel against any one of the basic beliefs and practices of the faith. It is in the interest of this eternal solidarity that Islam cannot tolerate any rebellious group within its fold. Outside the fold, such a group is entitled to as much toleration as followers of any other faith” (RQ, 137; italics mine).

For Iqbal eternal solidarity is fundamentally related to what looks like his equivocation on nationalism. In response to Nehru’s question about whether Iqbal’s objection to Indian nationalism extends to Ataturk, that is, to nationalism per se, Iqbal gives a remarkable answer. It is worth quoting at length: