The reason that I was aiming for a target

of three minutes producing 450 watts was,

obviously, that 450 watts was what Alex and

his boffins reckoned I needed to produce to

get the HPA off the ground. The three-minute

element was the time that an average HPA

flight lasts and, if I was going for speed, it

would be all that I would need. If I could crank

out the required 450 watts, it would, in theory,

take me to around 28 mph on the ground and,

once in the air, we might make 30 mph or more.

The big difference between this challenge and

the ‘Fastest Bike’ challenge was that riding

behind Dave Jenkins’s truck I was towed up to

the operating speed and my legs, with my feet

locked to the pedals, were turning all the way.

When the tow cable was released, I had to keep

my legs turning and increase the effort, which

was tough, but I wasn’t starting entirely from

scratch. With the HPA I would have to

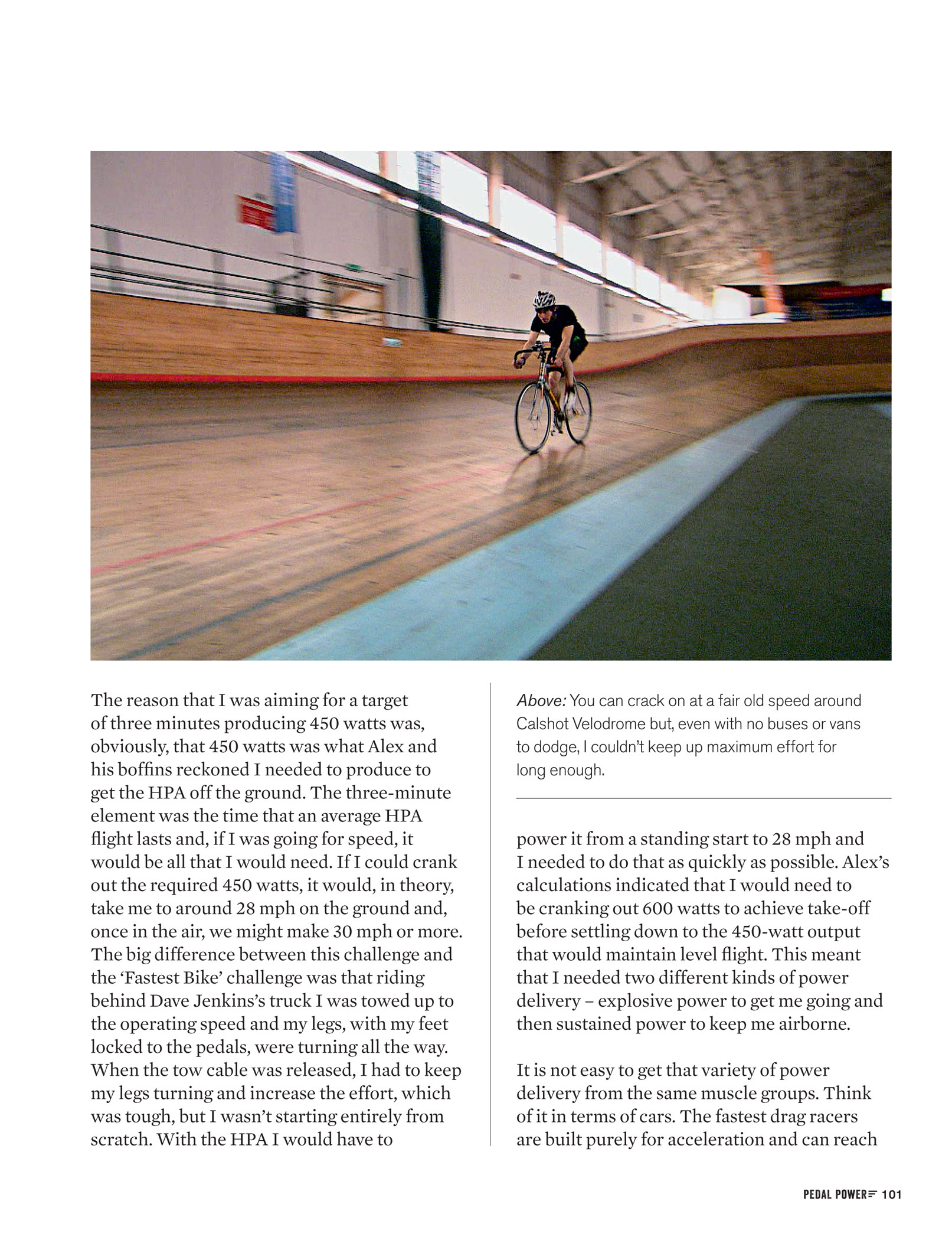

Above: You can crack on at a fair old speed around

Calshot Velodrome but, even with no buses or vans

to dodge, I couldn’t Keep up maximum effort for

long enough.

power it from a standing start to 28 mph and

I needed to do that as quickly as possible. Alex’s

calculations indicated that I would need to

be cranking out 600 watts to achieve take-off

before settling down to the 450-watt output

that would maintain level flight. This meant

that I needed two different kinds of power

delivery – explosive power to get me going and

then sustained power to keep me airborne.

It is not easy to get that variety of power

delivery from the same muscle groups. Think

of it in terms of cars. The fastest drag racers

are built purely for acceleration and can reach

PEDAL POWER 101