the propeller blades were also made mainly

from rigid foam.

The frame that attached the tail boom to the

bike, the boom itself and the main spar inside

the foam wing were all made from carbon-fibre

reinforced polymer, an incredibly strong but

amazingly light material. Saving weight, of

course, was essential and the whole aircraft,

with its massive wingspan, was designed to

weigh just 33 kilograms – that’s only about the

weight of an average Labrador dog!

Alex explained that pedalling the bike along

a runway would be what got me into the air.

If I could get to over 25 mph on the ground,

that would create enough air flow over the

wing to generate the lift we needed. Once

the wheels were off the ground, their job was

done and the propeller would take over. The

gearing on the bike was such that, by the time I

reached take-off speed, the propeller would be

operating at its optimum efficiency and would

provide all the thrust we needed.

With the wheels off the ground, I would no

longer have what little control I’d had when

steering the aircraft by using the bike. From

now on I would be steering the HPA the way

a pilot does.

As I learned from Guy Westgate, making any

aircraft go where you want it to is basically a

case of changing the shape of the wing. We’ve

seen how air flow over the wing generates lift,

as lower pressure is created above the wing

aircraft go where you want it to is basically a

case of changing the shape of the wing. We’ve

seen how air flow over the wing generates lift,

as lower pressure is created above the wing

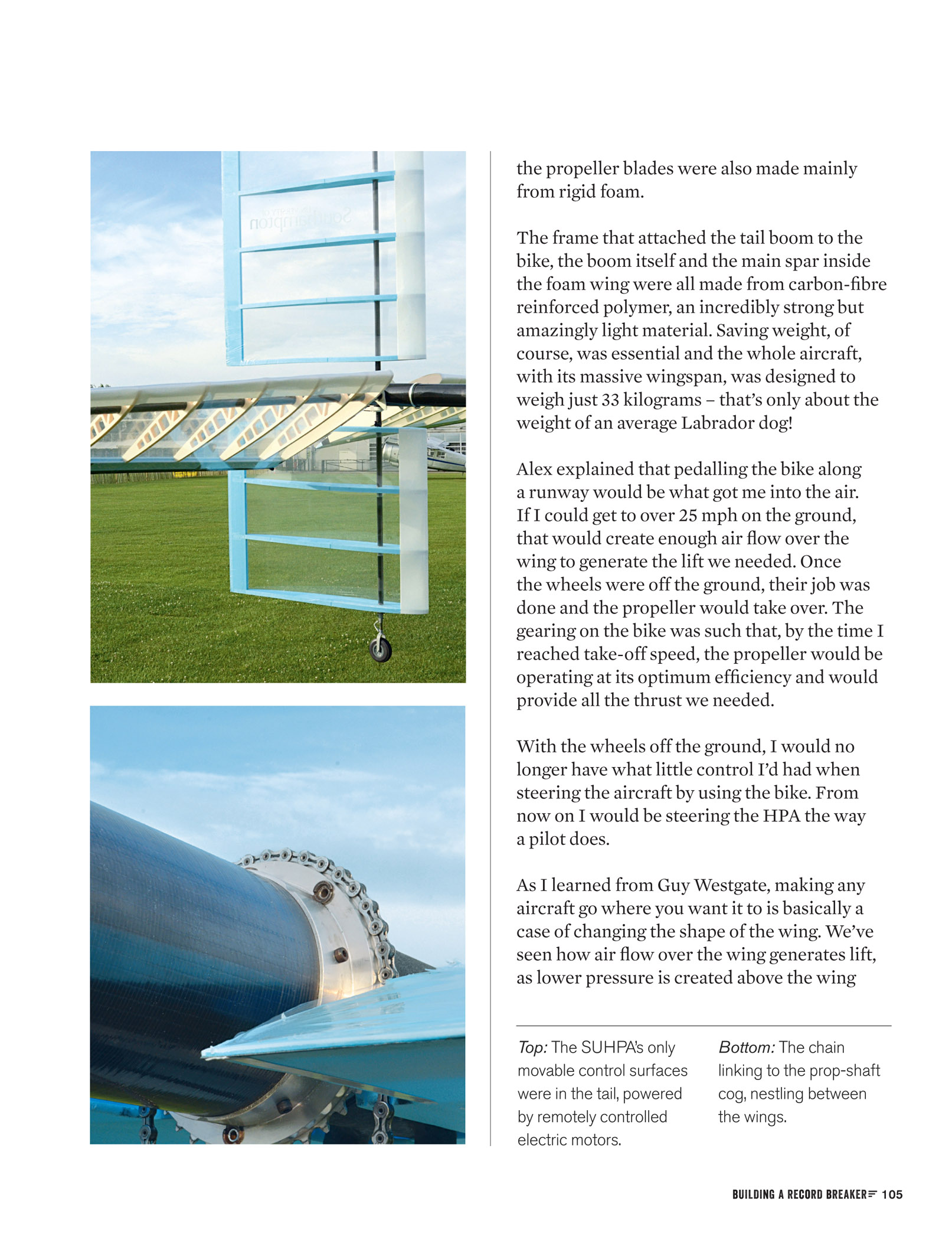

Top: The SUHPA’s only

movable control surfaces

were in the tail, powered

by remotely controlled

electric motors.

Bottom: The chain

linking to the prop-shaft

cog, nestling between

the wings.

BUILDING A RECORD BREAKER 105