Taking Control

Testing and Modifying

I’d been putting in the training hours and was

pretty confident that I would be able to supply

the required levels of power, but controlling

the HPA on take-off would be crucial.

HE latest calculations factoring in the

new propeller showed that the prop

reached its optimum efficiency at 28

mph – any slower than that and it would feel like

I was pedalling through treacle. That meant I

would have to be pedalling along the ground

pretty much at the record speed just to make sure

that I could achieve take-off.

T

The flaps in the tail would have to be raised to

bring the nose up. This would change the ‘angle

of attack’ of the wing – the angle at which it

cuts into the air flow – and generate that rush

of lift that I needed to get off the ground. Once

airborne, the HPA would suddenly become

vulnerable to any slight crosswind, having lost

the grip on the tarmac that helped me to keep it

heading in a straight line. I would have to use the

rudder to stay on course.

Rather than having a complicated arrangement

of control cables, Alex and his team had come

up with a clever solution. The rudder and

elevators would work just like those in a

model aeroplane using an RC (remote control)

handset. The plan was to attach the handset to

the handlebars, where I would have it within

easy reach.

Left: I concentrate hard on

keeping the model glider

‘flying’ straight and level in a

wind-tunnel-style flow of air.

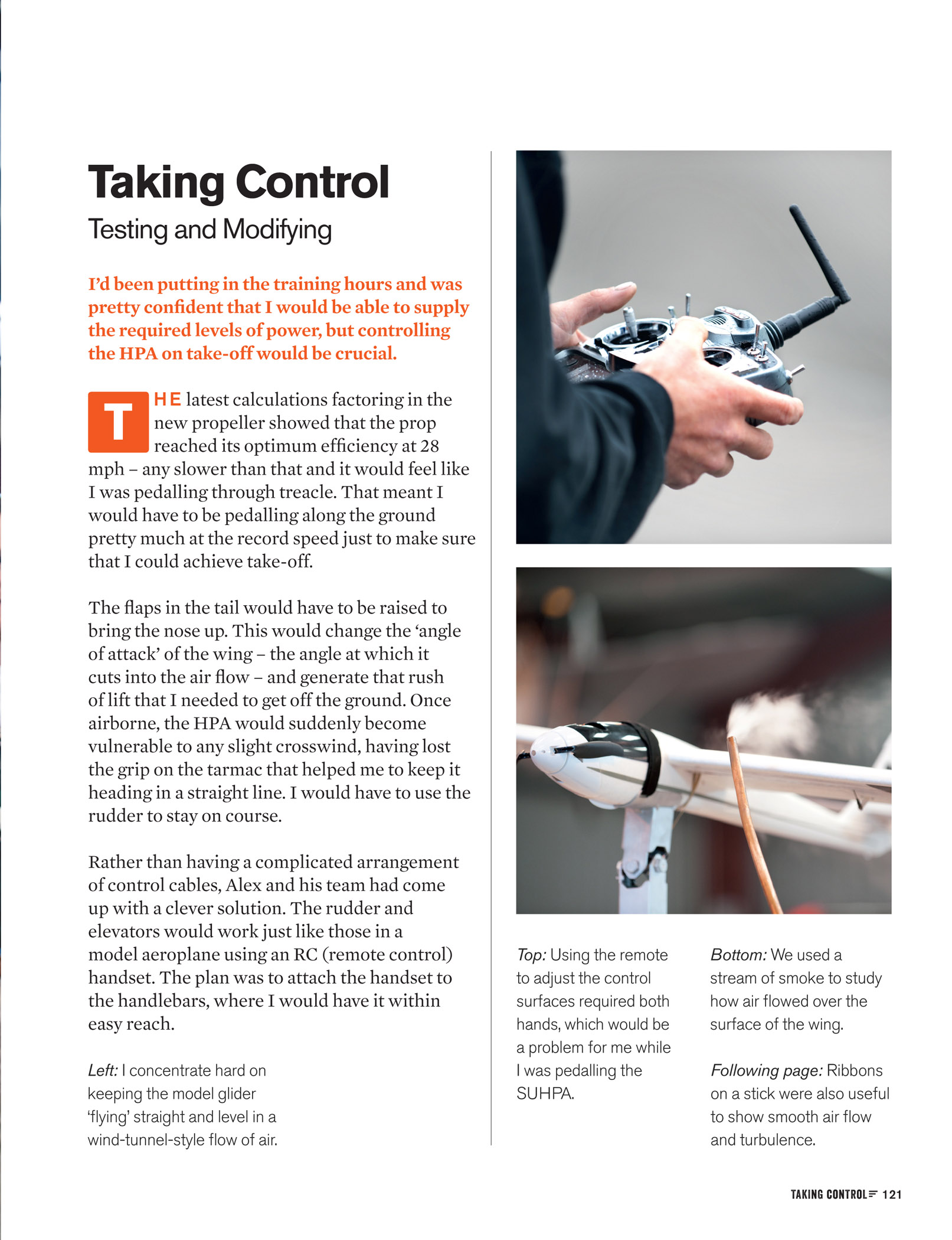

Top: Using the remote

to adjust the control

surfaces required both

hands, which would be

a problem for me while

I was pedalling the

SUHPA.

Bottom: We used a

stream of smoke to study

how air flowed over the

surface of the wing.

Following page: Ribbons

on a stick were also useful

to show smooth air flow

and turbulence.

TAKING CONTROL 121