For our carbon-fibre parts, the epoxy resin

was cured first by sealing the component and

its mould in a plastic bag and then pumping

out the air. When the carbon fibre and mould

are vacuum sealed together in this way, the

pressure of the outside air forces the cloth to

follow the exact shape of the mould. The whole

lot is then heat treated – baked in a kiln so that

the epoxy resin is activated and cures, setting

the carbon fibre into the shape we wanted.

The result is a smooth, shiny surface where

the carbon fibre has been formed against the

mould, although you can still see and feel

the fibre patterns on the inside of your new

component. For anything like a car body panel,

aircraft bodywork or our supersled, the smooth

outer surface is what matters most, because it

plays such a huge part in minimising drag.

Andy had actually suggested a modification

to the design that John Hart had come up

with, making the fairing more like a motorbike

fairing, so that I could look up – with my

eyes, that is, not sticking my head out into the

slipstream to look – and see where I was going,

and that wasn’t the only design modification

that was being taken into consideration.

The supersled was to have a number of new

additions. Its fairing would streamline me, the

forward area of the sled and the ski brackets.

In fact, Andy had suggested that the whole

sled could be made from carbon fibre, and this

option was being taken under consideration.

As well as the brakes that would rake the snow

under the front end of the sled, the Sheffield

team had also come up with the idea of fitting

another braking device – a parachute. It would

be attached to a boom that would reach out

beyond my legs, so that I didn’t get tangled up

in the parachute lines, and I would be able to

deploy it as an emergency brake.

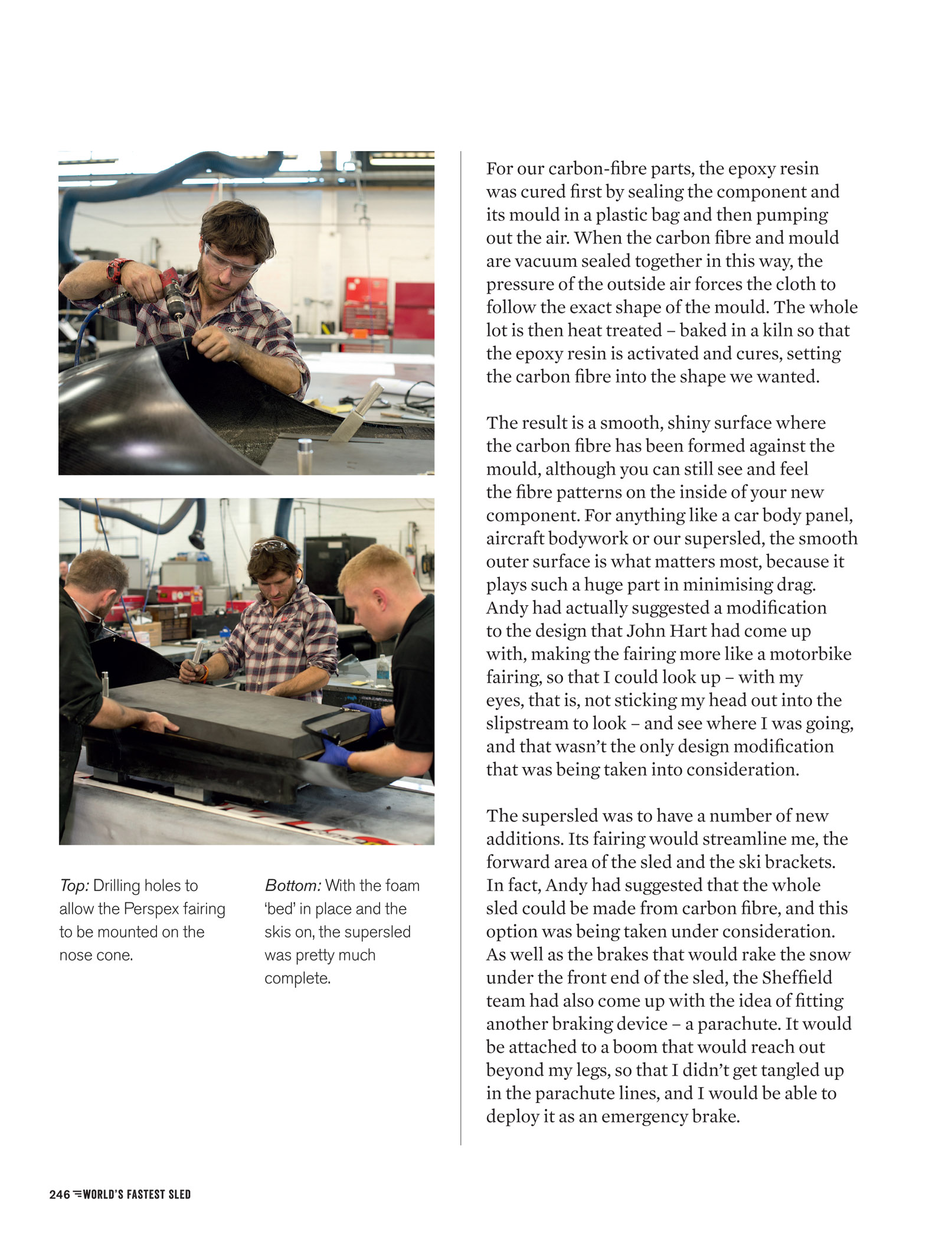

Top: Drilling holes to

allow the Perspex fairing

to be mounted on the

nose cone.

Bottom: With the foam

‘bed’ in place and the

skis on, the supersled

was pretty much

complete.

246 world’s fastest sled