448. [The use of n in place of s, as in ourn, hern, yourn, and theirn is not an American innovation. It is found in many of the dialects of English, and is, in fact, historically quite as sound as the use of s.] Joseph Wright, in his “English Dialect Grammar,” gives some curious double forms, analogous to hisn, e.g., hers’n in Cheshire, wes’n in Gloucestershire, and shes’n in Warwickshire, Berkshire and other counties. David Humphreys, in his glossary of 1815, listed hern as an Americanism, and Adiel Sherwood, in 1827, put hisn into the same category, though noting that “many of our provincialisms are borrowed from England.” Thomas G. Fessenden denounced both in “The Ladies’ Monitor,” 1818, as “provincial words … which ought to be avoided by all who aspire to speak or write the English language correctly.” Hern, in the form of hiren, is actually traced by the NED to 1340; ourn, in the form of ouren, to c. 1380; yourn, in the form of youren, to 1382, and hisn, in the form of hysen, to c. 1410. The grammarians of the Seventeenth Century declared war on all these possessives, and they have been denounced in the grammar-books ever since,1 but they survive unscathed in the popular speech. Curme indicates that the somewhat analogous thisn, thatn, thesen and thosen are now mainly American, but shows that whosen occurs “in the south of England and in the Midlands.”2 I find some exhilarating specimens in my collecteana:

Whatever is ourn ain’t theirn.

If it ain’t hisn, then whos’n is it?

I like thisn bettern thatn.

Let him and her say what is hisn and hern.

Everyone should have what is theirn.3

The last of these reveals a defect in English that often afflicts writers and speakers on much higher levels, to wit, the lack of singular pronouns of common gender.4 When, on September 27, 1918, Woodrow Wilson delivered a speech at a Red Cross potlatch in New York, he permitted himself to say “No man or woman can hesitate to give what they have,” but when the time came to edit it for his “Selected Literary and Political Papers and Addresses” he changed it to “what he or she has.” Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt fell into the same trap in 1941, when she wrote in “My Day”: “Someone told me last night that they …”5 On lower levels there are specimens almost innumerable, e.g., “When a person has a corn they go to a chiropodist.”6 Since 1858, when Charles Crozat Converse, the composer (1832–1918), tried to launch thon for he or she (and apparently also for him or her) and thon’s for his or her, various ingenious persons have sought to fill this gap in English, but so far without success. In the days of her glory as the queen of American schoolma’ams, Ella Flagg Young (1845–1918), superintendent of the Chicago public schools, asked the National Education Association to endorse hiser (his plus her) and himer (him plus her), but the pedagogues gagged. Both terms, however, were listed in the College Standard Dictionary, 1922, and in 1927 the late Fred Newton Scott (1860–1930)1 gave them a boost in a magazine article,2 though with hiser changed to hizzer, himer to himmer, and hesh (he plus she) added. In 1934 James F. Morton, of the Paterson (N.J.) Museum, proposed to change hesh to heesh and to restore hiser and himer. But none of these terms has ever come into use, even among spelling reformers, nor has there been any enthusiasm for the suggestion that English adopt the French indefinite pronoun on, which is identical in singular and plural.3

This on, in the Fifteenth Century, seems to have begot the English pronoun one, but the latter continues to have so foreign and affected a smack that the plain people never use it, and even the high-toned seldom use it consistently, at least in this country. In England one occasionally encounters a sentence through which ones run like a string of pearls, but in the United States the second and succeeding ones are commonly changed to he or his.4 In 1938 Gregory Hynes, an Australian lawyer, proposed se for he plus she, sim for him plus her, and sis for his plus her,5 but there were no audible yells of ratification. Nor did any follow the suggestion of a reformer of Primghar, Iowa, Lincoln King by name, that ha be used in the nominative case, hez in the possessive and hem in the objective. Nor the suggestion of a correspondent of the Washington Post1 that hes, hir and hem be adopted. Nor has thon ever got beyond the blueprint stage, though it made the Standard Dictionary and Webster 1934, along with thon’s. In despair of getting rid of the clumsy his or her otherwise, the late Stephen Leacock (1869–1944) once proposed a bold return to “the rude days … when we used merely to use his.”2

When, in 1926, the twenty-six linguists consulted by Sterling Andrus Leonard decided by a vote of 23 to 3 that it is me is sound English, and when, during the same year, the College Entrance Examination Board decided that nascent freshmen were free to use it, there was an uproar in academic circles but no noticeable jubilation among the plain people, for they had been using the form for centuries, and, what is more, they had been supported by many accepted authorities. Noah Webster allowed it in his “Grammatical Institute of the English Language,” 1784, and the celebrated John P. Mahaffy, provost of Trinity College, Dublin (1839–1919), not only allowed it but did a lot of whooping for it. In defense of it he devised the following dialogue:

A. We saw you and your wife on the beach this morning.

B. Oh, but we didn’t go out, so it can’t have been us.

What rational person, demanded Mahaffy, would have said, “it can’t have been we?”3 Rather curiously, American Speech, then edited by Dr. Louise Pound, took an editorial slap at the College Entrance Examination Board for its action,4 but this was atoned for in 1933 by the publication of a thundering defense of it is me by Wallace Rice.5 Rice mustered an array of sages ranging from Joseph Priestley to W. D. Whitney, from A. H. Sayce to Havelock Ellis, and from Thomas R. Lounsbury to Alexander J. Ellis, all of whom upheld it as sound idiom. He might have gone much further, for George H. McKnight had assembled dozens of examples of it is me and even of it is him and her from sound authors in the first issue of American Speech,1 and Otto Jespersen had brought together many others, and discussed the whole question with his accustomed good sense in 1894.2 In Shakespeare’s time the use of the objective pronoun had not yet established itself, and it is I was still the commoner form, though everyone will recall “Damned be him that first cries, ‘Hold! Enough!,’ ”3 but c’est moi, exactly analogous to it is me, had come into French in the Sixteenth Cenury, and it was soon influencing English.4 Today most American philologians, though perhaps not most schoolma’ams, would probably agree with Rice:

In the oral lessons given little children throughout the United States it is I is banged into their minds, and it is me is ranked with ain’t got none and a long list of similar vulgarisms.… What a waste! What is accomplished? I can remember back sixty years to my share in a frenzied dance of the first form at school, a dozen of us yelling “It is I, it is I!” in derisive contempt for minutes together after we had just been told for the first time that this alone was correct. I believe this to be the normal attitude of the right-minded boy, and one that persists through life.5

J. M. Steadman found support for this when, in 1937, he polled the students of Emory University at Atlanta, Ga., to find out what words and phrases they considered affected. His tally-clerks reported that first place was taken by limb, but that it is I was a good second, and ran ahead of expectorate.6 The Linguistic Atlas of New England7 shows that it is me prevails overwhelmingly in that region, even within the Boston area. Most of the informants who reported it is I confessed that their use of it was the product of belaboring by the schoolma’am. “Whenever I used me,” one of them said, “the teacher would say, ‘Who is me?,’ and then I’d change it quick.” But not many of those consulted recalled the horrors of education so clearly. “If somebody knocked at my door and called ‘It’s I,’ ” a New York school teacher told a writer for the New York Times in 1946,1 “I’d faint.” In late years it is me has even got support from eminent statesmen. When, just before Roosevelt II’s inauguration day in 1933, the first New Deal martyr, the Hon. Anton J. Cermak, was shot by a Nazi agent in Florida, he turned to Roosevelt and said, “I’m glad it was me instead of you,” and when, in March, 1946, the Right Hon. Winston Churchill made a recorded speech at New Haven he introduced himself by saying, “This is me, Winston Churchill.”2 Just why me has thus displaced I is in dispute. A correspondent suggests that it may be because I “suggests the ego too strongly,” but S. A. Nock thinks that it is because “the nominative I is colorless.”3

Various authorities, including Sir William Craigie,4 have suggested that the school grammarians’ war upon it is me has prospered between you and I, just as their war upon I seen has prospered I have saw. Wyld shows that you and I was thus used by English writers of the Seventeenth Century,5 and Henry Alexander produces examples from Pepys’s Diary,6 including between him and I. Robert J. Menner, dissenting from the Craigie theory, believes that the form came in because you and I were “often felt to be gramatically indivisible,” and because you “had come to be used for both nominative and accusative.”7 He says:

Pronoun or noun plus I after preposition and verb … is coming to be the natural usage at certain speech levels. Yet when the first personal pronoun precedes another pronoun or noun it is not normally in the objective form in careless speech. I heard the following from one man calling to another from a porch:

A. They invited me and Jim.

B. (Not having heard) What?

A. (louder) They invited Jim and I to their party.

This is natural syntax among people who are neither at the lowest speech level, where me and him and her are common as nominatives, nor at the highest, where family tradition or academic training make the standard literary forms prevail.

Craigie says that “no one would venture to carry this confusion so far as to say between you and we,” but I am not too sure, for I have encountered he in the objective following a preposition in the headline of a great moral newspaper.1 Mark Twain, a very reliable (if sometimes unconscious) witness to American speechways, used between you and I regularly until W. D. Howells took him in hand.2

Whom need not detain us, for it does not exist in the American common speech. Even in England, says the NED, and on the highest levels, it is “no longer current in natural colloquial speech.” When it is used on those levels in the United States it is frequently used incorrectly, as F. P. Adams used to demonstrate almost daily when he was conducting his newspaper column.3 It was rejected as “effeminate” by Steadman’s Emory University students,4 and got as many adverse votes as divine, dear and gracious (exclamation). Indeed, only sweet, lovely and darling beat it. The Linguistic Atlas of New England shows that its use there is pretty well confined to the auras of Harvard and Yale, and that even so it is rare. George H. McKnight has supplied evidence that many English authors of the first chop, including Richard Steele, Jane Austen, George Meredith and Laurence Housman have used who freely in situations where whom is ordained by the grammar-books,5 and I have no doubt that a similar inquiry among Americans would show many more. J. S. Kennedy, in 1930, printed a learned argument to the effect that the use of who in “Who did he marry?” need not be defended as a matter of mere tolerance, but may be accounted for on the ground that who, in this situation, is actually in the objective case, and has been so almost as long as you has been in the nominative.1 Just, he says, as “we have objective you and nominative you side by side, with ye preserved in the unstressed form in speech and also for very formal or archaic styles,” so “we have nominative who and objective who side by side, with whom reserved for more formal style, chiefly written.” In the common speech that is often substituted for both who and whom, as in “He’s the man that I seen.” Robert J. Menner has shown2 that that has also largely displaced whose, as in “He’s the fellow that I took his hat,” and that often even that itself is suppressed by periphrasis, as in “He’s the fellow I took his hat” and “She’s the girl I’ve been trying to think of her name.” The substitution of them for these or those, as in “Them are the kind I like,” was denounced as a barbarism of the frontier South and West by Adiel Sherwood in 1827, but it has survived gloriously and Wentworth offers examples from all parts of the country. Says Horace Reynold:

The use of them as a demonstrative is the mark of the manual worker. He finds these and those a little sissified and high-toned. He feels more comfortable in them shoes than in these shoes. Them is a word with a strong end; a man can get his teeth into it. Like the Irishman’s me for my, them beats these hollow for force. The Irishman’s “Give me some likker to temper me pain” has the same shirtsleeve, spit-on-me-hands wallop as the American’s “Shut them winders!”3

The Southern you-all seems to be indigenous to the United States: there is no mention of it in Wright’s “English Dialect Dictionary” nor in his “English Dialect Grammar.” What is more, it seems to be relatively recent. Wentworth quotes “I b’lieve you’ all savages in this country” from Anne Royall’s “Letters From Alabama,” 1830, but it is highly probable that this you’ all was simply a contraction of you are all. You-all struck a Northerner visiting Texas as “something fresh” so late as 1869, though he had apparently been in the South during the Civil War and was familiar with you uns.4 It was not listed by any of the early writers on Americanisms, and it is missing even from Bartlett’s fourth and last edition of 1877. On the question of its origin there has never been any agreement. In 1907 Dr. C. Alphonso Smith, then head of the English department at the University of North Carolina,1 published a learned paper on the subject in Uncle Remus’s Magazine (Atlanta), then edited by Joel Chandler Harris,2 in which he rehearsed some of the theories then prevailing. One, launched by a correspondent of the New York Times signing himself F. B.,3 ascribed the pronoun to the influence of the Low German spoken by German settlers in Lunenburg, Mecklenburg, Brunswick and Charlotte counties, Virginia. This correspondent said:

A little imagination will help us see two old dignitaries meet and address each other with “Good’n morn, wohen wilt ye all?” (Whence will ye already?). And after the confab is over they will express their regret by saying “Wilt ye all gaan?” (Wilt ye already go?) and the answer, “Ya, we wilt all foort” (Yes, we will already forth).

Another theory, also advanced by a correspondent of the Times,4 was thus set forth:

During the Cotton Exposition at New Orleans, 1885–86, I was in an official position which brought me into contact with hundreds of people from all parts of the Union, and as I was from Texas I seemed singled out for benevolent missionary work on the part of visitors from Northern States. With cheerful frankness they pointed out the many shortcomings of my people, and among them this idiom of you-all. I was boarding at the time with a Frenchwoman. I poured out to her my woes in English, and she expressed her sympathy in French. When I mentioned you-all as one of our sins she exclaimed: “Mais c’est naturelle, ça! On dit toujours nous tous, vous tous!”

Smith rejected both of these etymologies, and sought to show, by quotations from Shakespeare and the King James Bible, that you-all went back in England to Elizabethan times,5 but his quotations offered him very dubious support, for those that were metrical showed the accent falling on all, not on you, and in another part of his article he had to admit that this shift of accent clearly distinguished the Southern you-all from you all in the ordinary sense of all of you. He sought to explain the difference as follows:

In you all, all is an adjective modifying the pronoun you. But in you-all the parts of speech have changed places. All is the pronoun, standing for some other substantive, as folks, and you is the modifying adjective. This interchange is not without analogy in English. In such phrases as genitive singular and indicative present the first words were originally nouns, singular and present being adjectives. The plurals were genitives singular and indicatives present. But these phrases, borrowed from Latin, were exceptions to the usual position of words in English, which demands that adjectives precede nouns. The exception could not hold its own against the precedent established by the numberless phrases in which adjectives regularly preceded their nouns. After a while, such was the influence of mere position, the words genitive and indicative, standing in the normal position of adjectives, became adjectives, and the words singular and present, standing in the normal position of nouns, became nouns. Thus the plurals of these phrases are now genitive singulars and indicative presents. In similar fashion you all (pronoun plus adjective) passed into you-all (adjective plus pronoun).

Like any other patriotic Southerner, Smith devoted a part of his paper to arguing that you-all is never used in the singular, and to that end he summoned Joel Chandler Harris and Thomas Nelson Page as witnesses. This is a cardinal article of faith in the South, and questioning it is almost as serious a faux pas as hinting that General Lee was an octoroon.1 Nevertheless, it has been questioned very often, and with a considerable showing of evidence. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, to be sure, you-all indicates a plural, implicit if not explicit, and thus means, when addressed to a single person, you and your folks or the like, but the hundredth time it is impossible to discover any such extension of meaning. Eleven years before Smith wrote, in 1896, correspondents of Dialect Notes had reported hearing the pronoun in an unmistakable singular in North Carolina, Delaware and Illinois,1 and during the years following there had been a gradual accumulation of testimony to the same effect from other witnesses, including Southerners. In 1926 Miss Estelle Rees Morrison provoked an uproar by suggesting in American Speech that, when thus used in the singular, you-all was a plural pronoun of courtesy analogous to the German sie, the Spanish usted, and indeed the English you itself.2 In May, 1927, Lowry Axley, of Savannah, declared in the same journal that in an experience covering “all the States of the South,” he had “never heard any person of any degree of education or station in life use the expression in addressing another as an individual,” and added somewhat tartly that the idea that it is ever so used “by any class of people … is a hydra-headed monster that sprouts more heads apparently than can ever be cut up.” A correspondent signing himself G.B. and writing from New Orleans, offered Axley unqualified support three months later,3 but after two more months had rolled round Vance Randolph popped up with direct and unequivocal testimony that you-all was “used as singular in the Ozarks” and that he had “heard it daily for weeks at a time.”4

This encouraged Miss Morrison, and in 1928 she pledged her word that she had heard it so used at Lynchburg, Va., and also in Missouri.5 The Southern brethren were baffled by this, for the Confederate code of honor forbade questioning the word of a lady, so Axley had to content himself with slapping down a German professor who had stated incautiously, on what he had taken to be sound sub-Potomac evidence, that you-all was often reduced to you’ll.6 The professor, of course, was in error: the true contraction, as Axley explained, was and always has been y’all.7 At the same time Miss Elsie Lomax offered indirect testimony to the use of you-all in the singular by showing that a plural form, you-alls, prevailed in Kentucky and Tennessee. Early in 1929 a witness from Kansas testified that he was “addressed as you-all twice in the singular, in one day, at Lawrence,” the seat of the State university.1 The Southerners thus seemed to be routed, but in June, 1929, Axley returned to the battle with a polished reply to Miss Morrison, in which he argued that, even if you-all was occasionally used in the singular in the South, it was not “widespread,” and then retreated gracefully by referring unfavorably to Al Smith’s use of foist for first, to George Philip Krapp’s curious declaration that a.w.o.l. was pronounced as one word, áwol, in the Army, and to the imbecility of comic-strip bladder-writers who were trying to introduce I-all.2

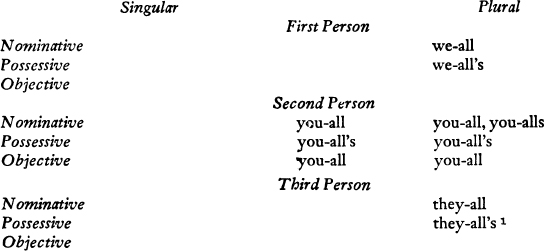

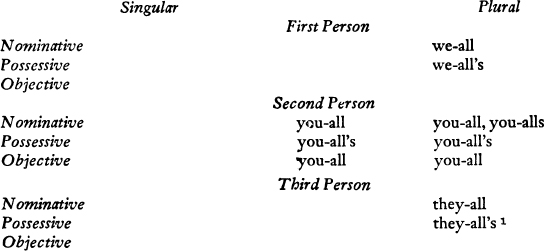

In the years following various other depositions reporting you-all in the singular were printed in American Speech,3 but the Southerners stuck to their guns, and in 1944 they got sturdy support from Guy R. Vowles, a Northerner who testified that, in nineteen years in the South, he had never heard you-all used in the singular.4 Mr. Vowles added that he had often heard a second all added to you-all, as in “Y’ll all well?,” and cited support for it in the German “Geht es euch allen gut?”5 The I-all denounced by Axley is not recorded in any dictionary save Wentworth’s, where it appears only as a jocosity by a radio crooner. But Webster 1934 lists he-all, though not she-all, him-all or her-all. It also lists who-all. Wentworth lists he-all from Webster and records they-all, me-all and both we-all and we-alls, but omits the others. Oma Stanley says in “The Speech of East Texas”6 that the white freemen of that area use you-all “only as a plural,” express or understood, but that the blackamoors “may use it with singular meaning as a polite form.” Its declension in the Ozarks is thus given by Randolph:

It will be noted that us-all, which Wentworth finds in Kentucky and North Carolina, is omitted, and also he-all, she-all, her-all, him-all, his-all and them-all. In the same paradigm from which I have just quoted Randolph gives the following declension of the analogous forms in -un:

| First Person | ||

| Nominative | we-uns | |

| Possessive | we-uns | |

| Objective | us-uns | |

| Second Person | ||

| Nominative | you-uns | |

| Possessive | you-un’s | |

| Objective | you-uns |

No singular forms and no third person forms are listed. Other observers, as Wentworth notes, have reported he-un, she-un, them-uns, this-un and that-un. Wentworth’s examples show that the use of -un is especially characteristic of Appalachian speech, though it has extended more or less into the lowlands. Some one once observed that the eastern slope of the mountains marks roughly the boundary between we-uns and you-all, and that the Potomac river similarly marks off the territory of you-all from that of the Northern yous. But such boundaries are always very vague. In 1888 L. C. Catlett, of Gloucester Court-House, Va., protested in the Century2 against the ascription of we-uns and you-uns to Tidewater Virginia speakers in some of the Civil War reminiscences then running in that magazine. He said: “I know all classes of people in Tidewater Virginia, the uneducated as well as the educated. I have never heard anyone say we-uns or you-uns. I have asked many people about these expressions. I have never yet found anyone who ever heard a Virginian use them.” But while this may have been true of Tidewater, it was certainly not true of the Virginia uplands, as a Pennsylvania soldier was soon testifying:

At the surrender of General Lee’s army, the Fifth Corps was designated by General Grant to receive the arms, flags, etc., and we were the last of the army to fall back to Petersburg, as our regiment (the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry) was detailed to act as provost-guard in Appomattox Court-House. As we were passing one of the houses on the outskirts of the town, a woman who was standing at the gate made use of the following expression: “It is no wonder you-uns whipped we-uns. I have been yer three days, and you-uns ain’t all gone yet.”1

In the same issue of the Century Val. W. Starnes, of Augusta, Ga., reported hearing both we-uns and you-uns among “the po’ whites and pineywood tackeys” of Georgia, and also in the Cumberland Valley and in South Carolina. Wentworth gives examples from every State of the South, both east and west of the Mississippi, and Miss Jane D. Shenton, of Temple University, tells me that you-uns and you-unses are also common at Carlisle, Pa.2 Jespersen says that the pronouns in -uns are derived from a Scottish dialect.3 The DAE omits we-uns, but traces you-uns to 1810, when it was reported in Ohio by a lady traveler.4 It was new to her, and “what it means,” she said, “I don’t know.” With this solitary exception, neither you-uns nor we-uns was recorded by any observer of American speech before 1860. Socrates Hyacinth said in 18695 that he had first heard the form in the South during the Civil War, and Bartlett said in his fourth edition of 1877 that it was “developed during the war.”

“The pronoun of the second person singular” – to wit, thou —, says Wright in “The English Dialect Grammar,”6 “is in use in almost all the dialects of England to express familiarity or contempt, and also in times of strong emotion; it cannot be used to a superior without conveying the idea of impertinence.… In southern Scotland it has entirely disappeared from the spoken language and is only very occasionally heard in other parts of Scotland.” In the United States it dropped out of use at a very early date, and no writer on American speech so much as mentions it. The more old-fashioned American Quakers still use the objective thee for the nominative thou, and the singular verb with it, e.g., thee is and is thee? The question as to how, when and why this confusing and irrational use of thee originated has been debated at length, but there seems to be no agreement among the authorities.1

Margaret Schlauch suggests in “The Gift of Tongues”2 that this-here, these-here, those-there, them-there, and that-there may reveal a pair of real inflections in the making. That is to say, -here and -there may become assimilated eventually to the pronouns.3 Wright says in “The English Dialect Grammar”4 that in some of the English dialects -here has begun to take on the significance of proximity, not only in space but also in time, and that -there similarly connotes the past as well as distance. Wentworth’s examples show that this-here frequently occurs as this-’ere, this-yere, this-yer, thish-yer, and this-hyar, with like forms for these-here, and that the -there of that-there, those-there and them-there changes to -ere, -ar, -thar, -air, -are and -ah. Witherspoon, in 1781, listed this-here and that-there among vulgarisms prevailing in both England and America, and noted that they were used “very freely … by some merchants, whom I could name, in the English Parliament, whose wealth and not merit raised them to that dignity.” This use, he added, exposed them “to abundance of ridicule.” Mark Twain used thish-yer in his “Jumping Frog” story, 1865, and in “Tom Sawyer,” 1876, and this h-yere in “Huckleberry Finn,” 1884. The NED traces this-here to c. 1460, but offers no example of these-here before the Nineteenth Century. It traces that-there to 1742. All these forms are constantly and copiously in use in the American common speech.1

1 In the Art of Reading and Writing English; London, 1721, Isaac Watts the hymn-writer hazarded the guess that they were used “at first perhaps owing to a silly affectation, because it makes the words longer than really they are.”

2 A Grammar of the English Language. Vol. III. Syntax; Boston, 1931, p. 528.

3 The origin of some of these -n endings is not settled, but it seems likely that the suffix may derive from own. Major William D. Workman, Jr., tells me that his own, as in “That is his own,” is in use in Charleston, S. C.

4 See AL4, p. 460.

5 The DAE says, in discussing everyone, that “the pronoun is often plural: the absence of a singular plural of common gender rendering this violation of grammatical concord sometimes necessary,” but under everybody it calls the sequence “incorrect.” I am indebted here to An Author Replies, by C. A. Lloyd, American Speech, Oct., 1939, p. 210.

6 A patient’s letter in the Journal of the American Medical Association, March 25, 1939. Singular nouns are followed by plural pronouns in many other situations. Here is a specimen from one of the late Will Rogers’s newspaper pieces, 1931: “This is the heyday of the shyster lawyer and they defend each other for half rates.” Also, singular pronouns are followed by plural verbs, as in the omnipresent he don’t. One of the late Woodrow Wilson’s daughters is authority for the statement that he used he don’t in the family circle. See Current English Forum, by J. B. McMillan, English Journal, Nov., 1943, pp. 519–20.

1 AL4, p. 134, n. 4.

2 The New American Language, Forum, May, p. 754.

3 French on – English one, by George L. Trager, Romanic Review, 1931, pp. 311–17.

4 AL4, p. 203, and Supplement I, p. 425.

5 See? Liverpool Echo, Sept. 21, 1938. I am indebted here to Mr. P. E. Cleator.

1 The Post Impressionist, Aug. 20, 1935.

2 My Particular Aversions, American Bookman, Winter, 1944, p. 39. Many other holes in the English vocabulary have been noted by the ingenious. See Needed Words, by Logan Pearsall Smith, S.P.E. Tract No. XXXI, 1928, pp. 313–29; Words Wanted in Connection With Art, the same, pp. 330–32; The New American Language, Forum, May, 1927, pp. 752–56; Verbal Novelties, American Speech, Oct., 1938, p. 240 (broster is proposed for brother and sister) and Needed Words, by H. L. Mencken, Chicago Herald-Examiner (and other papers), Sept, 10, 1934. See also AL4, p. 175.

3 I am indebted here to Mr. P. A. Browne, of the English Board of Education.

4 Dec., 1926, p. 163.

5 Who’s There? – Me, Oct., 1933, pp. 58–63. The Saturday Review of Literature, then edited by Henry S. Canby, jumped aboard the C.E.E.B. band-wagon on Aug. 14, 1926, p. 33.

1 Conservatism in American Speech, Oct., 1925, pp. 1–17.

2 Chapters on English; London, 1918, pp. 99–114. Reprinted from Progress in Language; London, 1894; second edition, 1909.

3 Macbeth, V.

4 Modern English in the Making, by George H. McKnight; New York, 1928, p. 195.

5 Who’s There? – Me, above cited, p. 62. Any American politician who proposed to change the name of the Why-Not-Me? Club, the trades union of the fraternity, to the Why-Not-I? Club would go down to instant ignominy and oblivion.

6 Affected and Effeminate Words, American Speech, Feb., 1938, pp. 13–18.

7 Vol. III, Part 2, Map 603.

1 The Way You Say It, by Doris Greenberg, Times Magazine, April 7.

2 This is Me, Time, April 1, 1946. There is a legend at Princeton (Princeton Alumni Weekly, Feb. 4, 1927, p. 521) that when James McCosh was president there (1868–88) he one night knocked on a student’s door, and on being greeted with “Who’s there?,” answered “It’s me, Mr. McCosh.” The student, unable to imagine the president of the college using “so un-grammatical an expression,” bade him go to the devil. But that was a long while ago.

3 It is Me, Saturday Review of Literature. The date, unhappily not determined, was after Aug. 14, 1926.

4 The Irregularities of English, S.P.E. Tract No. XLVIII, 1937, pp. 286–91.

5 p. 332.

6 The Language of Pepys’s Diary, Queen’s Quarterly, Vol. LIII, No. 1, 1946. Other examples are in The Sullen Lovers, by Thomas Shad-well, I, 1668, and The Relapse, by John Vanbrugh, V, 1698.

7 Hypercorrect English, American Speech, Oct., 1937, pp. 176 and 177.

1 Silva Says Killing Prompted by Insults at He and Buddy, Los Angeles Examiner, June 25, 1925, p. 2.

2 For example, in a letter from New York to the Alta Californian (San Francisco), May 18, 1867.

3 Horrible examples from Liberty, the Red Book, Common Sense, the Commonweal and an Associated Press dispatch are assembled by Dwight L. Bolinger in Whoming, Words, Sept., 1941, p. 70.

4 Affected and Effeminate Words, already cited.

5 Conservatism in American Speech, American Speech, Oct., 1925, p. 14

1 On Who and Whom, American Speech, Feb., 1930, pp. 25–55.

2 Troublesome Relatives, American Speech, June, 1931, pp. 341–46.

3 Piccalilli on the Vernacular, Saturday Review of Literature, Jan. 27, 1945, p. 14.

4 South-western Slang, by Socrates Hyacinth, Overland Monthly, Aug., 1869, p. 131.

1 Smith was a North Carolinian, born in 1864, and took his Ph.D. in English at the Johns Hopkins in 1893. After leaving the University of North Carolina in 1909 he became professor of English at the University of Virginia. In 1917 he moved to the Naval Academy as head of the English department, and there he remained until his death in 1924. He was the author of New Words Self-Defined, 1919, and many other books.

2 You All as Used in the South, July. This paper was reprinted in the Kit-Kat (Cincinnati), Jan., 1920.

3 Jan. 2, 1904.

4 M. F. H., Jan. 16, 1904. Both communications were printed in the Times Saturday Review of Books.

5 See also You-all in English and American Literature, by H. P. Johnson, Alumni Bulletin (University of Virginia), Jan., 1924, pp. 28–33; Shakespeare and Southern You-all, by Edwin F. Shewmake, American Speech, Oct., 1938, pp. 163–68; The Southerners’ You-all, by E. Hudson Long, Southern Literary Messenger, Oct., 1939. pp. 652–55, and You-all in the Bible, by Darwin F. Boock, American Mercury, Feb., 1933, p. 246.

1 In Dixie is Different, Printer’s Ink, Sept. 28, 1945, p. 23, D. C. Schnabel, of Shreveport, La., thus advised Northern advertisement writers: “And don’t – don’t – don’t have your copy character in the South saying you-all to one person. (Hollywood please copy.) It sounds as incongruous in the South as to say they is.”

1 Vol. I, Part X, 1896, p. 411.

2 You All and We All, American Speech, Dec., 1926, p. 133.

3 You-all, American Speech, Aug., 1927, p. 476.

4 The Grammar of the Ozark Dialect, American Speech, Oct., 1927, p. 5.

5 You-all Again, American Speech, Oct., 1928, pp. 54–55.

6 The professor was Walther Fischer, of Giessen: You-all, American Speech, Sept., 1927, p. 496.

7 Y’all, American Speech, Dec., 1928, p. 103.

1 More Testimony, American Speech, April, 1929, p. 328.

2 For more about I-all see Mr. Axley and You-all, by Herbert B. Bernstein, American Speech, Dec., 1929, p. 173.

3 For example, in You-all Again, by T. W. Perkins, April, 1931, p. 304 (in Arkansas), and More You-all Testimony, by Thomas C. Blaisdell, June, 1931, pp. 390–91 (North Carolina).

4 A Few Observations on Southern You-all, American Speech, April, 1944, pp. 146–47.

5 Further discussions are in The Truth About You-all, by Bertram H. Brown, American Mercury, May, 1933, p. 116; You-all Again, New York Times (editorial), Jan. 15, 1945; As It is Spoken, Journal of the American Medical Association (Tonics and Sedatives), May 20, 1944, and You-all, by H. L. Mencken, New York American (and other papers), July 16, 1934. See also Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations; eleventh edition; New York, 1937, p. 952.

6 pp. 98–99.

1 The Grammar of the Ozark Dialect, American Speech, Oct., 1927, p. 6.

2 Aug., pp. 477–78.

1 Notes on We-uns and You-uns, by George S. Scypes, Century, Oct., 1888, p. 799. There is a similar story in Americanisms: The English of the New World, by M. Schele de Vere; New York, 1872, p. 569. A Confederate soldier captured by Sheridan in the charge through Rockfish Gap is credited with “We didn’t know you-uns was around us all, and we-uns reckoned we was all safe, till you-uns came ridin’ down like mad through the gap and scooped up we-uns jest like so many herrin’.”

2 Private communication, July 14, 1937.

3 A Modern English Grammar; Heidelberg, 1922, Part II, Vol. I, p. 262.

4 A Journey to Ohio in 1810, by Margaret V. (Dwight) Bell; not published until 1920.

5 South-western Slang, Overland Monthly, Aug., p. 131.

6 p. 272.

1 The Speech of Plain Friends, by Kate Watkins Tibbals, American Speech, Jan., 1926, pp. 193–209; Quaker Thee and Its History, by Ezra Kempton Maxfield, American Speech, Sept., 1926, pp. 638–44; Quaker Thou and Thee, by the same, American Speech, June, 1929, pp. 359–61; Nominative Thou and Thee in Quaker English, by Atcheson L. Hench, American Speech, June, 1929, pp. 361–63; Some Peculiarities of Quaker Speech, by Anne Wistar Comfort, American Speech, Feb., 1933, pp. 12–14; and Thee and Thou, by William Platt, and The Quakers, by Isabel Wyatt, both in the London Observer, March 6, 1938.

2 New York, 1945, p. 147.

3 This is itself the product of such an assimilation. The NED says that it was formed “by adding se, si (probably the Gothic sai, see, behold) to the simple demonstrative represented by the and that.” It was, at the start, inflected for case and gender as well as for number, but “in Middle English these forms were gradually eliminated or reduced, until by 1200 in some dialects, and by the Fifteenth Century in all, this alone remained in the singular.”

4 p. 277.

1 See AL4, p. 452.