2

I never heard the voices of my family nor of my neighbors nor of the other men at the sawmill, yet when I read Faulkner I have an impression of things familiar, of coming home. I’m not in the least interested in ever returning to Dixie, but there’s a certain comfort in this identification, a fellow Southerner who can so richly convey, for better or for worse, the intricate peculiarities of our very distinctive region.

I turn the page. It’s the 5th of December and the uptown E is packed, some headed to Saturday night social events, some suburban holiday shoppers. Squeezed in the horde are four deaf students, their hands moving rapidly. The colored girl says Kennedy started the escalation, and the colored boy says the first U.S. casualty was way back in ’56, Eisenhower, and the Oriental girl says when they began defoliating the jungle that was the real beginning, and the colored boy says What? and the Oriental girl says My brother was there, it comes in big cans with an orange stripe, “Orange,” and the white boy says it started with the origins of the Cold War, and the Oriental girl says who cares where it started, three hundred thousand American troops there now, killing and dying and killing.

At Times Square there’s always the mass exodus of passengers replaced by a mass influx, the colored girl the only remainder of the students. Her flawless smooth skin is dark brown. She wears a miniskirt and tights and sports a large Afro. Moments after the doors have closed and the train pulled off I glimpse her stricken face, and I recognize her distress: she had wanted the uptown local train, the AA or CC, and just realized she’s on the E to Queens. The girl is not aware that I have been observing all this because I’ve learned to absorb the goings-on around me without appearing to have lifted my eyes from my book. She moves through the throng to the map and seems to make a plan. At 50th, the next stop, she exits the train, as do I. My building is three blocks away. I walk up the steps and notice there’s some sort of police action that has temporarily halted the uptown AA and CC. I feel someone tap my back.

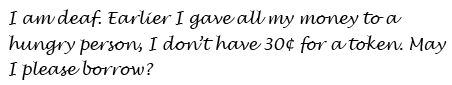

She stands before me with that panicked look again. She is five-five or -six, a good foot shorter than I, and stares up into my face as her lips move, apparently sound is being uttered from them as she gestures with exaggeration. She assumes I can hear. Her distorted sound might only confuse a hearing person but, fortunately, her strained pronunication allows me to easily read her lips. “Cross over?” She would like to know if at this station she can move from the uptown to the downtown side without exiting and thus avoid paying an extra fare. I smile sympathetically as I shake my head. She looks as if she’s going to cry. I don’t know what else to do so I turn away. She grabs my arm, a bit frantic. She has pulled out a small notepad and writes furiously.

I have many friends. Abigail the librarian and Lloyd the super and Joy the school principal and Perpétue the museum guard and none of them knows anything about me, no one has ever asked me a personal question and this has made for me a very culturally rich and safe life. I keep my chats with Perpétue brief, and holding conversations with hearing people who are not sign-speakers is exhausting for both parties so I’ve been able to maintain respectful boundaries with all of my good friends. To begin a conversation with a stranger in the sign language is to risk complications. I could give this young woman the thirty cents, then have her walk up out of the station to cross the street then back down into the station on the other side to take the E or the AA or the CC one stop downtown back to the Times Square station to then walk up and over from the downtown side to the up to wait for the northbound AA or CC.

But there’s an easier way.

I sign: Do you need the CC uptown?

She stares at me, startled that I am hand-speaking. Yes! I’m going to 94th and Amsterdam.

You can walk to Columbus Circle and catch it there. I’ll give you the thirty cents.

Thank you! Thank you so much!

And as I am reaching into my pocket for the quarter and nickel, her hands begin moving rapidly. She lives in Greenwich Village and never comes uptown but a friend of hers from college has just moved to the city and is having a housewarming party. It started at seven but then you know how parties go, you get there when you get there. She couldn’t come until now because of her Friday afternoon class with the people she was on the train with.

Yes, I thought you were students. We have come out of the subway and are walking up Eighth Avenue, the night clear, in the forties.

Continuing education students, I think you mean. I’m thirty-three. It was a fiction writing class. Have you ever written stories?

No.

I haven’t done it since Gallaudet. I’m really glad I went there. I liked D.C. After high school I debated whether to go to a regular college or deaf, but I guess I’ve always been around deaf people so I felt more comfortable there. My parents and most of my siblings are deaf.

Really?

Her fist nods briskly. I’ve never been to a housewarming before. I wasn’t sure what to bring so I brought wine. Do you think I should have brought something for the apartment? But I haven’t seen the apartment. So I just brought wine and I’ll ask Marielle when I get there if she needs anything for the apartment. That’s her name, Marielle. Well, actually, it was Mary Lou until she took the name Marielle in classe de français and kept it. The young woman smiles, rolling her eyes. Oh I love these decorations! I know it’s all commercial but I just can’t help it, I get in the spirit. I’m going home to South Carolina for the holidays. I have six brothers and sisters and they’re all deaf except for my sister Ramona. She’s the third oldest, I’m right behind her. We’ll go to church Christmas Eve and she’ll sing in the choir. She wanted to sing in her high school chorus in tenth grade but she was afraid it would insult our family and when my mother found out she was livid. So junior and senior year there she was, her whole deaf family in the front row watching her lips move. Were you born in New York?

I have held onto every word and still it takes me a moment to realize she has paused for a reply.

No. Alabama.

A fellow Southerner! I thought for sure you were native Gotham, you sign so fast! How long have you lived here?

It seems strange for her to remark on my velocity, given that her own hands have been flying a mile a minute.

Ten years.

Oh you’re a real New Yorker then! When I graduated from Gallaudet, I stayed in D.C. a while. Another English major I knew got me a job proofreading at her law firm. Then three years ago I was talking about coming to New York and I wrote to my old sophomore roommate who was already here. Well Toni tells me she’s about to move to Seattle to get married and her fiancé is allergic to cats so would I like to sublet her place and take care of her cat? Would I! The young woman stops a moment. You must think I’m some dingbat, walking around with no money. When I carry it I have a bad habit of spending it, on coffee, a candy bar, junk I don’t need and then I’m broke. Thank God I don’t smoke anymore. I smoked my freshman year, then my aunt died of diabetes, I quit cold turkey. I know diabetes isn’t lung cancer, but every day they seem to discover some new disease smoking causes, I’m not taking any chances. Now I can’t even stand to be around cigarette smoke though I know they’ll be smoking at the party, they always do. Do you smoke?

No.

So after spending way too much on crap I started leaving my apartment with no more than a dollar. But then right outside the building where my class was I saw this destitute man, skin and bones. I’d already bought my token to get to the party so I gave him the rest. I figured after I got to the party I could borrow thirty cents from somebody for the token home. So it would have been all okay if I hadn’t made that mistake just now and got on the E when I should have been on the CC. She shakes her head. That poor man had no shoes. In December! It made me feel grateful to have a job. Even if I hate it. Temped the first two years here, now I’m a secretary in an ad agency. I was told it’s the way you break in. Except I’m not sure anymore I want to break in. What do you do?

She’s a college graduate and I’m a janitor who never went to the first grade. I want to say I’m a teacher but I’d feel like a liar. At any rate it’s part-time, and I teach sign. Nothing impressive for her.

I’m a building superintendent.

She stares at me, wide-eyed. Free rent?

I smile.

Fantastic! You know, I’m thinking very seriously about a career change. I have a friend who works at the Bronx Zoo who thinks she can get me something. That’d be great, outdoor work. And I love animals! How old are you?

Now I truly consider lying. But I believe she has told me the truth about her age, it’s only fair. Only fair. My sigh is private.

Forty-seven.

Really? I would have thought a lot younger. Mid- or late thirties.

My face warm, crimson.

I never come uptown. I’m missing out on a lot, you know? You ever been to the Cloisters? Top of Manhattan?

Yes.

I’ve always wanted to go! She breathes in the air. What a beautiful night! What’s your name?

We are caught at the corner of 61st by a red light. I indicate for us to cross Broadway, and she follows. When we are on the sidewalk, I reply.

Benjamin.

Benjamin. And what’s your sign name?

As directed by my sign instructors I had created a concise moniker, an embellished B. But the name I grew up with, the name I have never mentioned to anyone in New York, is compact enough. I swallow before I form the two letters.

Hello, B.J. I’m April May June.

I stare at her. She smiles.

It started with me being born in April. And my parents the Junes had a sense of humor. What’s that?

Lincoln Center.

Lincoln Center? Wait. We passed Columbus Circle.

I thought I would walk you up to 94th. You can use your thirty cents to get home after your party.

She stares at me, and I know I have made a terrible, presumptuous mistake. Some strange man offering to walk her all that way, and up Broadway through notorious Needle Park in the 70s no less! What am I thinking?

Or I can just give you the other thirty cents if you want to get on the subway now. I keep my eyes low, fixed on her hands. I say, You’ll need the other thirty to get home later.

I was going to borrow it from somebody at the party.

I nod.

You got out of the train at 50th. You don’t mind walking so far out of your way?

And now I glance up and see she’s smiling. I tell her, I like to walk.

She takes her little notepad out and scribbles something, tears off the sheet.

My address. You can write to me sometime. Now she turns to Lincoln Center, across from where we are standing.

I swore I would never come here. They removed San Juan Hill to make way for this. It sounds Puerto Rican but it was black, a poor black neighborhood decimated. Did you know?

I shake my head.

Come on.

I follow her, and after navigating the heavily trafficked crisscrossing of Broadway and Columbus, we arrive at Revson Fountain, the centerpiece of Lincoln Center which currently houses the symphony, opera, and a theater, and has future plans for the ballet. Her hands are motionless now as we gaze at the gurgling flow. She smiles, the lights of the cascade dancing in her eyes. Finally she looks up at me, studies my face a moment before her hands gently speak. My sign name. And with a flourish she gives me her flowing, fused A M J.

The water suddenly shoots high into the air. April May June and I laugh, surprised, standing next to each other, mesmerized and washed by the crystal spray bedewing the crisp, clear night.