3

Someone once said of little Charlie Garstin that, with his angelic face, curly fair hair and big blue eyes, had he found himself lost in London in the morning, by nightfall he would have been adopted by a duchess. Had Garstin foreseen the scandalous mess that was to become his childhood then he might have been forgiven for giving this theory a try.

When still 19 Charlie’s mother Mary had fallen for a romantically named young army officer, Beau. They spent much of the summer of 1887 on the Kent coast, going for long walks and reading his detailed campaign diaries from Egypt, where he had already been awarded the Distinguished Service Order. He was in his early twenties, serious, about to embark for India and completely unable to consider the idea of marriage. They settled on ‘friendship with a capital F’ and so it was with a heavy heart that Mary reached Egypt that autumn for an extended stay with friends. There she met Mr Garstin, ‘a good looking, fair man with very cold blue eyes and close cut curly hair’. He fell in love with her immediately. She would later claim that the idea of being married (as well as the prospect of more trips to Cairo) enamoured her more than her future husband, but regardless they were married the next year. A daughter, Helen, was born in 1890, followed by Charlie in 1893, but by 1897, citing boredom as one of her excuses, Lady Garstin had begun a very public affair with a married army man.

Charlie’s father, Sir William Garstin, was a truly brilliant civil engineer who spent most of his only son’s childhood radically transforming the way in which the waters of the River Nile were utilised. Heavily associated with the Aswan Dam, eventually becoming Under Secretary of State for Public Works he was also responsible for buildings and antiquities, and in this capacity oversaw the building of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. ‘Will’s’ work weighed heavily on him and took him away from his wife, twenty years his junior. Mary later wrote her dramatic memoirs, casting herself as the ‘heroine’ and her lover as her ‘hero’. So her husband was to play the pantomime villain. He was certainly a very reserved man; she called him the ‘pink of propriety’ and lamented his inability to let flow any emotional outpouring. Mortified by her indiscretions but even more so by the idea of a divorce Sir William forgave her numerous times and blamed himself frequently before things came to a head at the turn of the century.

Lady Garstin never made any attempt to disguise the fact that she favoured her daughter. Little Helen was diabetic and consequently, before the advent of insulin, almost an invalid. ‘With her delicate health and passionate devotion … she so absorbed my love that Charlie had never been quite the same to me.’ Being parted from her, as would be the case if she left her husband, was more than she could stand and so she resolved to stay put. Helen sadly passed away in 1900 while her mother was in Cairo attempting to save her marriage. It proved the break she needed. Sir William and his wife mourned their little girl together but in the aftermath her affair was rekindled. Not without floods of tears, Charlie’s mother chose her lover over her 7-year-old son. The night before Lady Garstin despatched him in the hands of his beloved nannie to his father for good she watched his ‘lovely sleeping face’ on her bed. Her very public affair and Sir William’s decision to divorce her, not to mention the fact that she would reside with her still-married lover, sealed her fate. Lady Garstin made no attempt to contest the divorce hearing and, as was the norm, was forbidden any contact with her son beyond the concession of a brief note each month to assure her of his continued good health. The matter was taken seriously. On the one occasion that she defied the ruling she was caught out and when Charlie arrived at Eton she received a letter from a solicitor, informing her that if she took advantage of his unguarded presence in the town to make contact with him then he would be removed from the school immediately.

Charlie did not stay at Eton as long as he should have. With a proficiency for modern languages and his father’s insistence that war was imminent he spent time in Germany before returning home in 1912 to go to Sandhurst and fulfil his dream of joining the cavalry. Returning to England he had not long begun his training when his mother was coincidentally invited by a friend to stay on the premises. She wouldn’t have recognised him. Charlie was a slim young man of 18 now and she was rocked by his resemblance to his father. The ice-blue eyes, the curly hair, the fair complexion. He had inherited some of Sir William’s bearing too. Whilst still at Freiburg the local cavalry regiment, much enamoured by their visitor, had thrown him a farewell dinner. He was utterly shocked that the conversation revolved around the deficiencies of the British Army and their impropriety caused him to get up and leave his startled hosts after the soup; an anecdote that was still being passed around Eton with much amusement several years later. But if his father’s propriety was high on his list of personality traits, Charlie’s mother found that so too was warmth and kindness. He chattered away excitedly with none of the inhibitions that had rendered communications with her husband impossible. He seemed to understand, if not condemn, his father’s shortcomings. She learned of his love of languages and how he had recently qualified as a German interpreter.

As Charlie left her, Lady Garstin was full of hope:

Could it not be arranged that his father and I should, for his sake, [meet again]. Surely, surely it could be arranged? He would write immediately to his father and tell him of our meeting and what it had meant to him. This was only a short parting now, only a very short parting.

Charlie promised her that nothing would keep him from her again. Sir William, however, was furious and threatened to disinherit his boy if he had contact with his mother, and though Charlie walked into the night in his uniform, promising her that they would be together soon, she would never see him again.

Charlie embarked for France with the rest of the 9th Lancers in 1914. The Great Retreat began in earnest the day after Mons. For the OEs, present shrapnel was a hideously recurring theme on Monday 24 August. George Fletcher wrote home, sending his father his tales of ‘Blood and Thunder’, and lamenting the ‘swish of shells’ over his head. Blasted from German field guns and exploding above their target, the shrapnel sprayed in all directions, whistling ‘like a cat … miaowing over … Bang – interval – whe-e-ew MIAOW! BANG!!’ George was not the only one running scared. Aubrey Herbert didn’t mind admitting that he was terrified:

A shell burst over my head. I jumped to the conclusion that I was killed and fell flat. I was ashamed of myself before I reached the ground, but, looking round, found that everybody else had done the same.

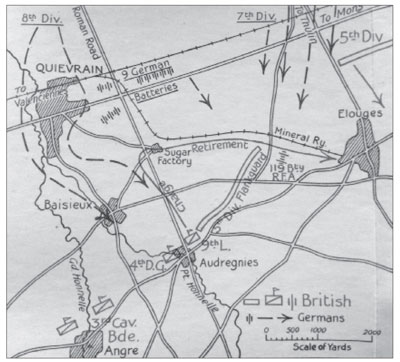

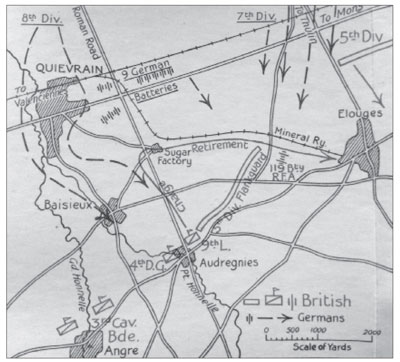

The Ninth had not been amongst the troops heavily involved in Britain’s opening engagement against the Germans the day before. In fact, whilst chaos descended on the canal to the north, elements of the cavalry restocked their stores. Others enjoyed a relative lie-in and a homely breakfast provided by local nuns. Aside from a quick evening excursion in search of phantom Uhlans their cavalry brigade, comprising the Ninth, the 4th Dragoon Guards and the 18th Hussars, had had a quiet day. At dawn on 24 August it was scattered around the vicinity of a small town called Elouges, some 15 miles to the south-west of Mons. Less built up, it was still mining country, with a light, mineral railway dissecting the terrain and more telltale slag heaps dotted around sugar-beet fields. It was more open, but a maze of sunken roads, fences and scattered buildings still made it less than ideal for mounted troops.

Men of the brigade had been standing to all night with their horses saddled and ready to move, listening to the sound of the guns in the distance and watching as the wounded and refugees streamed down the main road. At 4 a.m. Francis Grenfell was ordered to take B Squadron forward to investigate what might be occurring back towards Mons. Cautiously they trotted into Thulin. They came under enemy fire almost immediately, metal raining down on them from where the Germans had taken control of a bridge over the canal to the north. Francis’ horse Ginger was killed and an officer was wounded by a flying piece of shrapnel to the chest.

For the first, and as it turned out, the only time, the Grenfell twins came under fire together. In danger of being outflanked by a large body of enemy troops they climbed the high ground out of Thulin and dismounted, unleashing a torrent of rifle fire. The advancing enemy troops halted and B Squadron took advantage of their pause to slip back to the rest of the regiment where collectively they began retiring south-west with the rest of the BEF. For once, the terrain worked in their favour. They were able to move back leisurely, using random cinder heaps and embankments on either side of the roads as cover. Nevertheless the enemy artillery kept coming. More shrapnel exploded overhead, taking chunks out of man and horse alike, wounding one officer and killing another’s charger. From their position to the south they remained under heavy fire while they awaited further developments. Aeroplanes buzzed overhead, betraying their position to the German gunners and A Squadron took useless potshots at them with their rifles.

Riding from regiment to regiment, overseeing the whole affair was Brigadier General Henry de Beauvoir de Lisle or, more simply, Lady Garstin’s ‘Beau’. They had not been in contact since her downfall and he had come a long way since those heady days walking by the sea in Kent. The decision to abstain from marrying her had proved an astute one on his part, for since he had left her in 1887 he had spent a stint at the Staff College, assumed command of a cavalry regiment and served on the General Staff at Aldershot before 1911, when he assumed command of the very brigade that her son Charlie was to join less than two years later.

Halfway through the morning de Lisle sent his orderly officer, an Irish OE of the 10th Hussars named Pat Armstrong, off to a nearby infantry general with a message. When he came galloping back an hour later it was with an urgent appeal for assistance. The last contingent of the BEF trying to retire from Mons was in trouble. A gap had opened in the line and they were in danger of being overrun. Beau’s brigade was closest and he burst into action immediately, pushing his three cavalry regiments north again. The Ninth, along with the 4th Dragoons, found themselves deployed to a small village named Audregnies, on the left of two of the troubled infantry battalions.

Lucas, Charlie and the Harvey brothers arrived on the north side of the village, had their men quickly dismount and commenced a sustained, long-range barrage of rifle and machine-gun fire on the advancing German troops. Back with the Dragoons, another young OE named Roger Chance had also arrived. Both regiments had been in the village little less than an hour when de Lisle himself came thundering down the road and drew up abruptly alongside Colonel Campbell. ‘I’m going to charge the enemy,’ he blurted out. ‘The 4th Dragoon Guards will attack on your left.’ His instructions were clear. As soon as Campbell saw Roger Chance and his fellow officers emerge from the village and deploy northwards he was to send at least two squadrons of the Ninth with them.

The idea of an all out, Napoleonic-style cavalry charge at this juncture was patently ludicrous. There were no significant bodies of enemy troops close enough to make it justifiable for a start as that left them without a target. Therefore, the logic behind two cavalry regiments riding into the artillery duel between the Germans and vastly outnumbered British artillery was questionable. The ground they would be galloping over was not unproblematic. It undulated, albeit gently; the corn in the surrounding fields had already been cut so only stubble remained, but the crops themselves lay about in piles, or ‘stooks’. Add to that all the sunken lanes, railway cuttings, wire fences and quickset hedges, behind or amongst all of which enemy troops could be lurking, then the scenario became increasingly perilous. Nonetheless Colonel Campbell was forced to order his men ready immediately. Under fire, the scene was already chaotic and behind some houses the Ninth mounted up. Meanwhile the 4th Dragoon Guards were jumping into their saddles and tearing off down a cramped, narrow lane towards the edge of the village.

No sooner had Charlie, Lennie and Douglas got ready than the Dragoon Guards were seen emerging from the other side of Audregnies and they were off. They moved off at a trot and rode knee to knee. Campbell wheeled his arm in an underarm circle, the signal for canter, and as their speed increased, they lowered their lances. One of the officers, ‘Riffkins’, had got caught up in a wire enclosure away from the body of the squadron with an interpreter and almost missed the show. ‘I wasn’t behind the house!’ he moaned. Suddenly he was under a terrific volley of infantry fire and the French interpreter grovelled beside him. He was being left behind. ‘Moving off at a gallop – have a good start of me – What the hell are they doing?’

Beau de Lisle had pushed a dismounted contingent of the 18th Hussars to the north of Audregnies with a battery of the Royal Horse Artillery to take up a defensive position. ‘Suddenly there was a tremendous increase in the hostile gun and machine-gun fire to our left,’ they noted. The Ninth burst from Audregnies, Francis and Lucas leading their squadrons. The Hussars watched as the rest of the brigade came over the skyline, picking up speed, galloping out across the front of their line. They swept over a gently sunken road, the Ninth leading, the Dragoons slightly behind and to the left. Seeing the cavalry advance with the evident intention of shock action the Germans took cover behind corn stooks and slag heaps, and opened fire with their rifles. ‘On we go through a hail of bullets and shrapnel – must be charging,’ Riffkins surmised. ‘Find my sword and draw it – Cannot see any Germans.’

As they thundered on it rained metal, a dozen shells flashing and bursting at a time. If there had been a coherent target they would not have seen it. The dust kicked up by hundreds of horses blinded them. The crack of bullets and the thumping of shells added to the thundering of hooves. Shrapnel was exploding in amongst them and it was ‘a very inferno of shell and small-arms fire’. Next to Chance, a sergeant crouching in his saddle was ‘blasted to glory’ and Roger felt what was left of him ‘go patter to earth’ around him. One of the 4th’s interpreters, the elegant Vicomte de Varvineur was ‘blown to tatters’ by a direct hit from a high explosive shell. Horses began to get away from their riders. Roger Chance was clinging on with one hand for dear life. Through ‘sleeting bullets’ he passed isolated little bodies of German troops in the cornfields but that was it. One man somersaulted down to the ground, another officer’s horse was hit and he tumbled to the floor with it. His squadron rode over him, then a machine-gun section and finally a passing horse smashed him in the face before he passed out. The column formations of both regiments were long gone in the melee. One of the the infantrymen on the ridge that they had been sent to assist was up on a bank to their right and he watched riderless horses go stampeding past him down an empty country road in what he called a ‘useless waste of life. All to no purpose’.

Rivy Grenfell was not with B Squadron that afternoon. He had been commandeered by de Lisle as a galloper after the morning reconnaissance with Francis. ‘A rather weary task on a heavy horse.’ He had spent most of the day alone, riding about the Belgian countryside, under fire, looking for staff officers and passing along orders for the brigade. Searching for de Lisle, he rode into Audregnies and found it almost empty. He was told that his regiment had just charged. Then he was engulfed by a herd of wounded horses … ‘galloping everywhere … bullets and shells were falling like hailstones.’

With no target in sight, the charge began petering out and self-preservation began to take hold. As one trooper went cascading to the ground, his horse going from under him, he heard Campbell give the order for the mess of cavalrymen to right wheel away from the German guns. As he lay cowering on the floor, they began to change direction ‘like a flock of sheep’.

On the main road, a 1½mile north of Audregnies, a red-brick sugar factory with a tall chimney and a large yard dominated the vicinity. It appeared to be their best chance of cover, but as the cavalrymen approached their horses reared. The brick yard itself was bordered by a high fence and all about the property were more wire barriers. Bundled into a corner the horses crowded in and chaos ensued. The factory itself was now being used for target practice by the German artillery. ‘We simply galloped about like rabbits,’ Francis recalled. ‘Men and horses falling in all directions.’ In the intolerable heat of mid afternoon the squadron commanders of the Ninth began frantically to try to bring about some order. Any sort of formation had disintegrated completely and there was no telling Lancers from Dragoons. Behind a house where he had taken cover, Francis frantically tried to find a trumpeter to give some kind of signal, but there was nobody in sight. He began blowing on his officer’s whistle whilst he ‘cursed with vehemence anybody he found out of place’.

Not everybody had made for the sugar factory. Some men, whether by providence or by choice, were dismounted and now they were attempting to keep the enemy at bay with rifles and the assistance of the artillery that continued to pound relentlessly, throwing shells high over their heads. Others had seized a cottage nearby and from there Dragoons were running out into the open to collect the wounded. Riffkins had hidden behind one of the isolated mounds of slag with Colonel Campbell, who instructed their crowd to hold the factory before riding off to find de Lisle. He could make no sense of it at all. ‘A few silly fire orders – nothing to shoot at – then the Colonel disappears – for three days.’

Lucas, now the senior officer on the scene, had also found ‘scanty cover’ behind yet another pile of cinders and like Francis was attempting to organise the mixture of troops that had joined him. He took his ramshackle outfit and attempted to get them out of harm’s way to a nearby quarry through yet another tornado of shrapnel. Francis was in a similar predicament. The house he had been using as shelter had been blown to pieces and now, cowering under an embankment, he began attempting to sort out his following. Recalling that on one occasion the regiment had been ordered to trot in South Africa under heavy fire he attempted to use the same method to keep the men together.

In the middle of the afternoon it looked to Campbell and Mullens as if their regiments had evaporated. Coming out of the cover of his embankment with the resilient band that included Lennie and Douglas, Francis Grenfell ran headlong into the 119th Battery of the Royal Field Artillery. They were in a terrible state. Outnumbered three to one, they had been engaged in a duel with German gunners and the results were telling. All about the guns lay the pulverised remains of more than a quarter of the men. Now, ordered to disengage, their Commanding Officer Major Alexander did not have enough men to get his guns out of harm’s way. While they were discoursing on this predicament Francis fell victim to yet more shrapnel.

‘It felt as if a whip had hit me,’ he wrote afterwards. Pain shot through his hand and his leg. One of A Squadron’s officers, a young OE named ‘Bunny’ Taylor-Whitehead, was on hand and got to work with a handkerchief to try to stem the blood spurting from the wound. Out came a copy of the Field Service Regulations. They leafed through the pages trying to find out how to apply a tourniquet. ‘Of course we found out how to stop blood in every other part of one’s body except one’s hand.’ Eventually they got it together but by then things had begun to spin a little for Francis. He suddenly remembered that in the wallets of the horse he had inherited he had seen a flask of brandy, so he promptly emptied it. ‘I now felt like Jack Johnson instead of an old cripple.’

As well as being mauled by three batteries of German artillery, the 119th and their cavalry helpers were also under a sustained and intense tirade from machine guns and rifles, and Francis’ first task, having volunteered to help, was to find a suitable place for them to extricate their guns to. Leaving everybody else under the embankment he mounted his borrowed horse and got on his way, riding out through the silent British guns alone, as the German’s continued to shell with enthusiasm. He made it to safety, found a safe place to aim for and then had to ride back. It might have been the brandy talking but he was determined to retain his dignity in front of the troops. ‘It was necessary to go back through the inferno as slowly as possible, so as to pretend to the men that there was no danger and that the shells were more noisy than effective.’

Having informed Major Alexander that he had found a way out, Francis was told that the draught horses were gone. The only way to save the guns was to drag them out of the way by hand. Minus a decent amount of blood, ever so slightly influenced by alcohol and having just survived a game of chicken with the German artillery, Francis was full of confidence. Ordering his crowd to dismount in front of their horses he gave a rehashed version of the colonel’s speech at Tidworth and asked for volunteers to help manoeuvre the guns to safety. Hands shot up, including Bunny, Lennie and Douglas. In all eleven officers and a host of men offered their hands. Francis glowed with pride. ‘Every single man and officer declared they were ready to go to what looked like certain destruction.’

Then they got to work. One by one they ran out into the storm of metal and started attempting to drag tons of heavy machinery out of enemy range. Slowly the guns had to be turned in the right direction and then the hauling began. In direct enemy range, one gun had to be dragged over the body of its fallen gunners. In all, Francis thought that they had managed to accomplish the task with the loss of only three or four men, although they had to return more than once and the enemy reached within 500 yards before the last gun was dragged to safety. He reflected on the actions of his men proudly. ‘It is on occasions like this that good discipline tells. The men were so wonderful and steady that words fail me.’

Francis held on, light headed until Lucas arrived and assumed command, and then he began to collapse. His friend was kind yet firm in talking him into the idea of getting into an ambulance. Francis’ fingers were badly cut up and a piece of shrapnel had torn a lump out of his thigh. He had a bullet hole in his boot from the morning, another through his sleeve, he had been knocked over by a shell and his horse had been shot; ‘so no-one can say I had an idle day’, he said drily. A French staff officer took pity on him and drove him to Bavay, where, as luck would have it, his good friend the Duke of Westminster was there to mollycoddle him. Rivy, having been ordered to rally what troops he could on the way south, soon arrived too. Dejectedly wondering what he could do to find news of his twin, he found that he was already in the town. Francis thought much more of his brother’s exploits on that first day of the retreat than he did of his own. He told their friend John Buchan, author of The 39 Steps, that his twin’s ‘solitary act of reconnaissance, all alone, was braver than anything he did; a raw civilian riding for hours under heavy fire on a tired horse on missions of vital importance’.

The nation disagreed. In August 1914, specialist publications about the war sprang up. One in particular took its coverage of the supposed exploits carried out by mounted troops to obsessive proportions. The charge led by the 9th Lancers, with all its romanticism and connotations of the charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava, was irresistible. With truth not getting in the way of a good story, artist’s impressions of Francis, leading his men with resolve on his face, in point-blank range of a gun emblazoned the pictorial press. The Germans cower in the foreground, a trooper who had lost his horse charges the enemy on foot, sword in hand. As far as the British public were told, the enemy had captured the British guns and were hell bent on turning them on their owner’s troops. Francis and his men stormed to the rescue. Starved of information about the chaotic retreat, John Buchan remembered (and not without irony) how in the confusion of those first weeks of war ‘the exploits of the Ninth emerged as a clear achievement on which the mind of the nation could seize and so comfort itself’.

For Francis, convalescing at his uncle’s house in the knowledge that not only had none of those guns fallen into German hands but that he himself had not been within a few hundred yards of any concentration of enemy troops, it was embarrassing. Despite his arguable display of bravery, his only concern was his squadron and how they were faring in France. ‘I have never felt such a fool in my life,’ he declared, by now aware that he had been nominated for a Victoria Cross, which baffled him. ‘After all, I only did what every other man and officer did who was with me.’ Thanks to a ‘lot of rot’ penned by ‘infernal correspondents’ he was receiving fan mail and all kinds of exalted visitors. The king himself had stopped by, as had Mrs Asquith, who was thoughtful enough to ask after Rivy. There were fellow OEs: Prince Arthur of Connaught who sat with him for an hour and the legendary Field Marshal Lord Roberts, who had begun his own cavalry career lifetimes ago, a full decade before the Indian Mutiny. He badgered him for every last detail: who did they charge, how and with what aim? In his weakened state, all Francis could do was watch the clock, entertain well-wishers and take every ‘wild story’ as it came. In France though, just as he feared, the war continued without him and the Ninth would suffer many more hardships before he managed to find his way back.

On 24 August, as darkness descended and rain began to fall, Lucas took charge of the tattered remains of the regiment. He fell back, taking a third of the Ninth’s strength, including the Harvey brothers and Bunny Taylor-Whitehead, over the border into France and on to the town of Ruesnes. Other straggling collections of men were arriving in other little towns along the frontier, like Wargnies-le-Petit, where Colonel Campbell had found 100 more cavalrymen. The BEF had evaded von Kluck again, but to the survivors of the charge it seemed like a catastrophe. That evening, with the men scattered, it seemed as if two regiments had simply disintegrated. The 4th Dragoon Guards could only find seven of its officers and only eighty men had answered one roll call. Not until the end of the week, when the various contingents began collecting at St-Quentin, did it transpire that things were not at all as bad as they had seemed.

As it turned out, one single officer of the 9th Lancers had been killed that day, and it was Charlie Garstin. One late summer morning his mother was cutting out garments for soldiers at her dining-room table, surrounded by pins, patterns and fabric. The door opened and her friend George, ‘with The Times in his hand and his face working awkwardly’, called her out of the room. ‘Mary,’ he stammered, ‘Mary darling.’ But he could not say it. He could only point to the obituary column with a trembling hand. Sir William made no contact with her and she died believing he had failed to tell her of Charlie’s fate out of spite. In actual fact there had been some confusion as to what had happened to Charlie and the answers lay with a prisoner, which disrupted the flow of information.

Another officer of the 4th Dragoon Guards had crawled into a cowshed with a broken leg and found several other wounded men. Shortly afterwards a German officer appeared ‘with a tiny popgun of a pistol’ which he kept trained on them as he inspected his new prisoners. More men were marched in whilst, as darkness set in, the Germans set fire to two haystacks and began throwing rifles and saddles into the blaze. ‘The merry popping of small-arm ammunition commenced’, bullets whizzing in their direction. Their captors brought wine for them and danced about the burning haystacks like demented shadows to the sound of two accordions, ‘a weird sight in the fitful light’.

The wounded British men were ushered and carried to a convent in Audregnies. One officer was lying there several days later with some 200 other men when the local priest arrived at the window with an exhumed body. The villagers had buried a British officer in some haste and the father had decided that he ought to be properly identified. It was Charlie. The identification process was repeated for two Cheshire officers and then all three of them were conveyed to Audregnies churchyard.1

Charlie Garstin was 20 years old when he charged at Audregnies. Rivy Grenfell had run into Colonel Campbell as he searched vainly that afternoon for Beau de Lisle. On the same fruitless mission they sat together. ‘He had been ordered to charge towards Quievrain,’ Rivy recalled. ‘Why, he did not know, as there was an open space for about a mile and he had lost nearly all his regiment.’ ‘Balaclava like,’ the newspapers called it. If a futile action, with a ludicrous and unrealistic objective that the man who ordered it would try and wash his hands of responsibility for was what was meant by that, then it can be said to be true. That night the commanders of the Ninth and the 4th Dragoon Guards were seething with rage at the man who had issued the order that had seemingly cost them so many soldiers. When someone sought to cheer up Campbell by telling him that he had been nominated for a Victoria Cross he snapped. ‘I want my squadrons back,’ he retorted, ‘not VCs or medals.’ In his official write up, Beau de Lisle held firm to the view that he had merely told his regimental commanders that it ‘might be necessary’ to charge. All of the evidence to the contrary, though, placed the responsibility for this botched footnote in the Great War in his hands; and with it too the death of Charles William North Garstin, his former sweetheart’s only son.

Notes

1 The body of Charles William North Garstin was relocated to Cement House Cemetery in the 1950s.

Diagram showing the charge of the 9th Lancers at Audregnies