Meet the Round Table

Thirty Friends Together

No essence can be measured by a yardstick.

—Heywood Broun

Julius Tannen, Beatrice and George Kaufman, Atlantic City, 1925. ◆ ◆ ◆

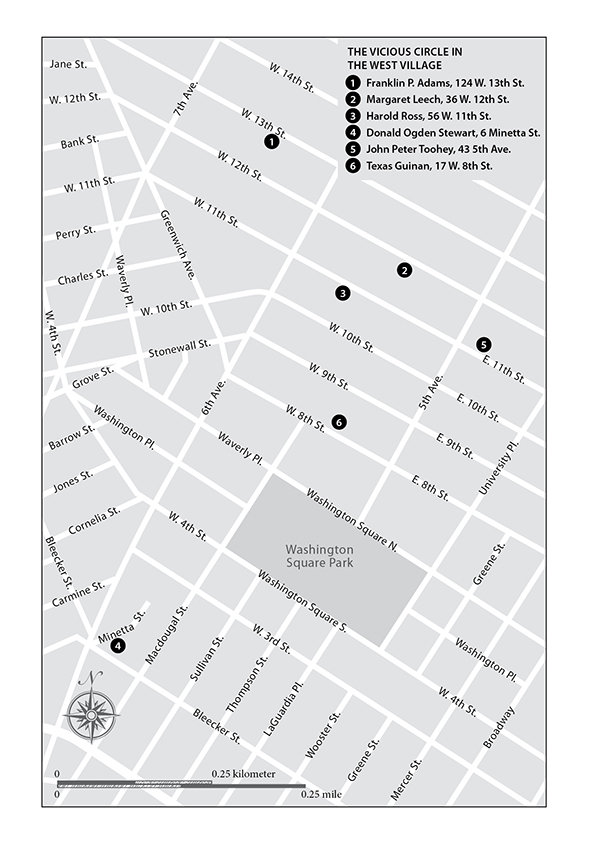

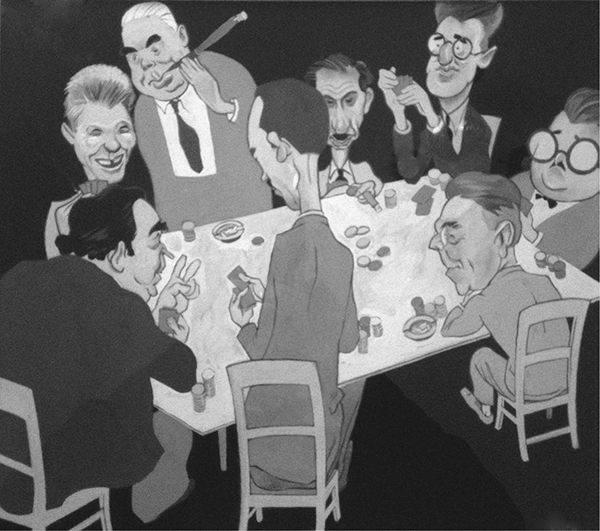

Separating fact from fiction in telling the history of the Round Table is a job for Sisyphus. “We all loved each other,” Marc Connelly recalled not long before he died in 1980. “We hated to be apart. After lunch we went to somebody’s house and figured out someplace to have dinner.” That much is true. Otherwise, dates are sketchy. Most accounts contradict others. Biographies repeat the same anecdotes with different protagonists. Quips, quotes, and jokes are all attributed to different people. Some believe the group lasted ten years; others put it between six and eight. By the time the stock market crashed in 1929, the members of the Vicious Circle had gone their separate ways, although many stayed close friends for the rest of their lives. Here are brief biographies of the complete Algonquin Round Table.

F.P.A. wrote more than two million words during his career. ◆ ◆ ◆

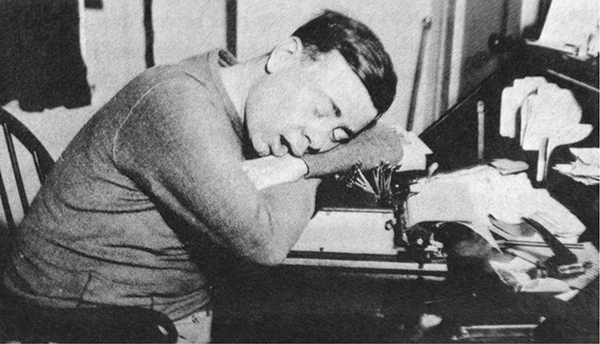

The dean of the Round Table and New York’s most popular newspaper columnist for two generations was Franklin Pierce Adams. For nearly forty years his columns appeared in New York newspapers. His readers knew him as “F.P.A.,” and he accepted submissions from readers, calling them “contribs.” Landing in F.P.A.’s column was a coup. He ran early material by George S. Kaufman, James Thurber, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Deems Taylor, and E. B. White. He also included scores of poems by Dorothy Parker. (“He raised me from a couplet,” she later quipped.)

Born in Chicago on November 15, 1881, the son of a dry goods merchant, Adams spent a year at the University of Michigan but withdrew after the death of his father. Following a stint in the insurance business, Adams landed a job at the Chicago Mail, where he wrote his first column. But he was itching to head to New York; he had his eye on a pretty actress named Minna Schwartze, two years his senior. His editor wrote to the managing editor of the New York Evening Mail and helped him to secure a position there.

In their parlor at 124 West 13th Street, Frank and Esther Adams placed two pianos. ◆ ◆ ◆

At age twenty-two, Adams began his “Always in Good Humor” column at the Evening Mail, an afternoon paper locked in a circulation war with other dailies. The column launched on October 21, 1904, and it was a hit. With his newly minted status, Adams married Minna Schwartze on his twenty-third birthday, a few weeks later. Mayor George B. McClellan presided over the City Hall ceremony. The couple’s first apartment was in a brownstone at 247 West 50th Street in Hell’s Kitchen.

Soon after, Adams renamed his column “The Conning Tower” for the armored pilothouses on battleships. While other writers penned pieces about the Astors and Vanderbilts, Adams preferred to write about regular people. He sprinkled his columns with what he was doing, where he went, who beat him at tennis, and what his wife said about it. Thousands of readers knew about his home life, what he ate, what shows he saw, and even his cat.

In 1911, he began his “Diary of Our Own Samuel Pepys” column (which continued for 2.5 million words, through 1934). In 1919 he and Minna were living at 603 West 111th Street, just west of Broadway, in Morningside Heights. In 1920 they moved around the corner to 612 West 112th Street, up the street from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. The next year Adams left the Tribune for the World. By then the Round Table was in full swing, and F.P.A. was the senior member.

F.P.A. divorced Minna in 1924, shocking readers who had devoured details about his personal life for almost twenty years. He took a five-month break from the column, and in Greenwich, Connecticut, on May 9, 1925, married Esther Sayles Root, a friend of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s, and fifteen years younger than his first wife. The couple had three sons and a daughter. By 1928 the growing family lived at 124 West 13th Street and later at 26 West 10th Street. Of the former location, E. B. White said: “I used to walk quickly past the house in West 13th Street between Sixth and Seventh where F. P. A. lived, and the block seemed to tremble under my feet—the way Park Avenue trembles when a train leaves Grand Central.”

Robert Benchley

Among the funniest writers of the twentieth century, Benchley was a study in contrasts. A straitlaced, Harvard-educated office worker, he married his college sweetheart, volunteered to help underprivileged boys, and eschewed alcohol. But something snapped after he joined the Vicious Circle in his thirties. He fell into heavy drinking, carefree spending, and young mistresses.

Benchley transitioned from a small Broadway appearance to two decades in Hollywood comedies. ◆ ◆ ◆

Robert Charles Benchley was born on September 15, 1889, in Worcester, Massachusetts. An unremarkable student, he graduated from Harvard in 1912. He and his college sweetheart, Gertrude Darling, married in June 1914 and had two sons. In 1916 he worked briefly on the New-York Tribune as a reporter, a job procured with the help of F.P.A. Benchley failed, though, admitting that he wasn’t cut out to be a newspaperman.

He kicked around town doing small writing jobs until 1919 when Frank Crowninshield, right-hand man to publisher Condé Nast, tapped Benchley to be the first managing editor of Vanity Fair. He was working at the magazine at 19–25 West 44th Street, alongside Parker—ultimately his closest friend—and Robert E. Sherwood, when the Round Table began. When Parker was dismissed from the magazine in January 1920, Benchley and Sherwood resigned in protest. The men joined Life, a weekly humor magazine, with Benchley as dramatic critic. “The theatre would be much better off if everyone, with the exception of me and a few of my friends, stayed at home,” he wrote that year. “And even then I should like to go alone once in a while.”

Benchley’s life changed in 1922. He appeared in a revue staged by the Vicious Circle, doing a parody of a small-town community speaker. His performance of “The Treasurer’s Report” brought the house down. Audience members Irving Berlin and producer Jed Harris begged him to join the Music Box Revue, an annual production of comedy, music, and dance at the Music Box Theatre, 239 West 45th Street. Benchley asked for $500 a week (about $6,700 today); to his total shock, the producers agreed.

Benchley became an instant celebrity, and fame followed him into the early talking pictures and, later, radio broadcasting. His first film, The Treasurer’s Report (1928), was the first all-talking film. The Library of Congress later added his second, The Sex Life of the Polyp (also 1928), to the National Film Registry for preservation in perpetuity. In 1935, How to Sleep won the Academy Award for best short subject comedy.

Benchley and MacArthur lived here; today it’s the Marriott East Side. ◆ ◆ ◆

Benchley’s family lived in Westchester County while he rented rooms in Manhattan. He shared a room with Charles MacArthur in one of the city’s first skyscrapers at the Shelton Club Hotel, 525 Lexington Avenue (today the New York Marriott East Side). Benchley later boarded at the Algonquin, but the nonstop party in his suite drove him across the street to the Royalton Hotel, 44 West 44th Street, where he lived for more than twenty years. Benchley became a victim of his own success. His writing talents landed him performing jobs that paid him large sums, but then he had no time to write, so he quit altogether.

Heywood Broun could write a newspaper column in less than thirty minutes. ◆ ◆ ◆

The quintessential newspaperman in a rumpled suit, Broun lived life to its fullest, never doing anything in moderation. He sported a long overcoat (sometimes of raccoon) and a fedora with phone numbers written inside. He chain-smoked and never left home without his hip flask of gin and bitters. He loved high-stakes poker, roulette, and the ponies, but he also wrote beautifully and voluminously—as much as two thousand words a day for more than twenty years.

Broun was born at 55 Pineapple Street in Brooklyn Heights on December 7, 1888. His father owned a successful printing and stationery business. Like Dorothy Parker, he was raised on the Upper West Side, growing up in a brownstone at 140 West 87th Street. He attended the prestigious Horace Mann School for Boys, then in Morningside Heights, where he was voted best all-around man. He also attended Harvard, but to his lifelong chagrin didn’t graduate in 1910 because he couldn’t pass French.

Heywood Broun took up painting as a form of stress relief. He painted only landscapes, calling each one an “Early Broun.” ◆ ◆ ◆

Returning from Cambridge, he took up journalism, covering sports for the New York Morning Telegraph. Two years later he asked for a raise and was fired, at which point he joined F.P.A. at the Tribune. By age twenty-two, Broun had become a fixture at ballparks, boxing rings, and horse tracks, friendly with editors, prizefighters, and taxi drivers alike. Broun often played cards in the afternoon with Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson, and in the evening hit the town with Russian ballerina Lydia Lopokova, to whom he was engaged briefly. For the next decade he worked as a reporter, rewrite man, copyreader, Sunday magazine editor, drama critic, book reviewer, and columnist.

Broun was an iconoclast, and he married one, too: Ruth Hale, a proto-feminist. The couple had an open marriage and three activities in common: writing, fighting, and moonlighting. They were among the first to join the Vicious Circle, and they counted group members among their closest friends.

When they married in 1917, Broun was dramatic editor of the Tribune, but he still lived with his parents, at 195 Claremont Avenue, in Harlem. By 1920, the couple and their young son, Heywood III, lived at 200 West 56th Street, today the Manhattan Club. The following year Broun joined the World, and as his social consciousness increased, his genial columns became serious political discussions, drawing national attention. During the Sacco-Vanzetti trial, his views differed sharply with management, who sacked him. He ran for Congress to represent the Upper East Side as a socialist—unsuccessfully—but he attacked indignities wherever he saw them, and helped displaced workers during the Great Depression.

The brownstone owned by Broun and Hale at 333 West 85th Street, near Riverside Park, was one of the central residences of the Round Table. Broun won the mortgage at the card table, but several years later the family had to move after he lost the deed, also while gambling. Parties at the house were raucous and legendary, and temporary lodgers here included Grant, Ross, and Taylor.

In the Thirties, Broun helped found the Newspaper Guild and traveled the country as a labor organizer, campaigning for employment reform and fair wages. He moved to a farmhouse outside Stamford, Connecticut, and his marriage to Hale ended in 1933. He married dancer Connie Madison in 1935, and Broun’s name became closely linked to prominent left-wing causes of the era. Broun spent most of the Thirties as a labor organizer, and campaigned for social issues like equal employment and fair wages.

Connelly coasted on his early fame for most of his life. He worked in theater and film for the rest of his career, but he peaked by age thirty-nine. ◆ ◆ ◆

To be a Round Table member, you had to be talented, witty, and charming. Connelly was all three, in spades. When the mood struck him, he wrote marvelous plays and short stories. Some of the greatest Vicious Circle quips came from his lips, and he was a supremely gifted raconteur, renowned in elite New York society as the ultimate dinner guest. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1930, and coasted on that fame for fifty years.

Marcus Cook Connelly was born on December 13, 1890, in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. His father owned a boardinghouse, and young Marcus grew up among the transient hustle-bustle of a hotel. He attended a local boarding school and fell in love with the traveling theater shows that passed through nearby Pittsburgh. His family couldn’t afford to send him to college, so he went to work in the advertising department of the Pittsburgh Press, which led to a reporter’s job and a humor column when he was barely out of his teens.

He wrote one-act plays for a local community theater and was just twenty-two years old when the first was produced. His big break came when a producer took one of his shows to New York to test the waters. Connelly went along, but didn’t have the train fare to return to Pittsburgh. He stayed in Manhattan with a friend and looked for a job instead.

By 1915 Connelly was selling light pieces to the New York Sun and the weekly humor magazine Life. He also wrote title cards for silent pictures in Chelsea, New York’s movie hub then. The next year he moved into an apartment with seven struggling writers and artists, including illustrator John Held Jr., at 39 West 37th Street, but had a hard time making the $2 weekly rent. Connelly avoided serving in World War I because he had to support his widowed mother. He spent the war years writing theater news for the New York Morning Telegraph, a paper that contained so much Broadway gossip that its nickname was “the chorus girl’s breakfast.” There Connelly met Broun, a drama critic for the paper.

Connelly also crossed paths with George S. Kaufman, who had the theater beat at the Times. In 1920 powerful producers George C. Tyler and Harry Frazee tapped Connelly and Kaufman to create a comedy vehicle for rising young English actress Lynn Fontanne. The pair turned to Algonquin pal F.P.A. for inspiration. Adams had a running character in his column, a ditzy girl named Dulcy (after Dulcinea from Don Quixote), who always found herself in trouble but somehow managed to save the day. Connelly and Kaufman took her as inspiration and wrote the snappy three-act Dulcy, which opened on Broadway in August 1921 at the Frazee Theatre (formerly at 254 West 42nd Street). It launched Fontanne to superstardom and ran for almost 250 performances.

Both Marc Connelly and Robert E. Sherwood married Madeline Hurlock, a silent-film star. They all remained friends. ◆ ◆ ◆

Connelly and Kaufman followed their success with To The Ladies (1922), starring a young Helen Hayes; Merton of the Movies (1922); the Kalmar and Ruby musical Helen of Troy, New York (1923); the flop, The Deep Tangled Wildwood (1923); the hit, Beggar on Horseback (1924); and another musical, Be Yourself (1924). They last collaborated on The Wisdom Tooth (1926) before parting ways.

Two years later Connelly received a copy of Roark Bradford’s Ol’ Man Adam an’ His Chillun, the Old Testament retold as family stories handed down from field hands in the Old South. From it he created a legendary show and a rousing success that touched audiences and broke racial barriers in American theater. The Green Pastures featured the first large all-black musical cast on Broadway. Playing at the Mansfield Theatre (now the Brooks Atkinson, 256–262 West 47th Street), the show ran for almost 650 performances from 1930 to 1931, and earned Connelly the Pulitzer.

Connelly had lived at 47 West 37th Street with his mother, Mabel, in the Twenties. When his success came, they moved to 21 West 87th Street. In 1930, when his play was the biggest hit on Broadway, they still resided together, at 152 West 57th Street.

Edna Ferber

The hardest-working member of the Round Table was Edna Ferber. The Times claimed that for years Ferber wrote a thousand words a day, six days a week, 350 days a year. Ferber took issue with being remembered as an Algonquin habitué, though. In her autobiography, she put her attendance at about four times a year. The reason? She was always working. She wrote eight plays, twelve novels, and more than a hundred short stories. In the whole group, she was the most commercially successful.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Edna Ferber was inducted into the New York State Writers Hall of Fame in 2012. ◆ ◆ ◆

Like many Round Tablers, her roots lay in the Midwest. She was born on August 15, 1885, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, to storekeepers, but instead of college, where the good student hoped to go, she went to work. At age seventeen, she became a reporter in Appleton, Wisconsin. Working on the Daily Crescent and, later, the Milwaukee Journal gave her the tools she used as a novelist. She developed a keen eye for detail and a knack for talking to strangers, meeting traveling salesmen, store clerks, laborers, and farmers that eventually populated her fiction. She liked and wrote about ordinary men and women, and her mother provided the biggest inspiration for her work.

In her early twenties, she battled depression, returning home to convalesce. She bought a used typewriter, and shortly thereafter cranked out her first short story, “The Heroic Heroine,” about an unattractive, ungainly woman, for Everybody’s Magazine, which paid her $50 for it. She quit journalism to write more short stories, including scores featuring Emma McChesney, a traveling underwear saleswoman. Her first novel, Dawn O’Hara, The Girl Who Laughed (1911), tells the story of a woman newspaper reporter in Milwaukee.

Ferber lived in Chicago when she wrote her early short stories. In 1912 she moved to the Hotel Belleclaire, 250 West 77th Street, in New York. She often lived in residential hotels, including the Hotel Majestic on the corner of 72nd and Central Park West, but a plaque commemorates her on just one of them, at 50 Central Park West, where she lived for seven years. In 1929 she moved to the Barbizon Hotel for Women (called Barbizon 63 today), 140 East 63rd Street.

Ferber had her biggest success in 1924 with So Big, the story of a Chicagoland farmwife and her struggle with life and the soil at the turn of the century. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, was adapted into film twice, and sold more than 250,000 copies. Ferber wrote only about Americans: life on the Mississippi in Show Boat, the development of Oklahoma in Cimarron, oil-rich Texas in Giant, and New York in Saratoga Trunk.

Ferber adored Broadway and collaborated with George S. Kaufman several times before World War II. They made for a rocky team, but they made it work. Ferber and Kaufman cowrote Minick in 1924, based on one of her short stories, which played for five months at the Booth Theatre. They teamed up again for more hits: The Royal Family (1927), based on the Barrymore family, and the classics Dinner at Eight (1932) and Stage Door (1936).

Ferber never married. “Being an old maid is like death by drowning,” she said. “A really delightful sensation after you cease to struggle.”

Margalo Gillmore in Eugene O’Neill’s The Straw (1921). ◆ ◆ ◆

The Algonquin nickname of the youngest member of the Round Table was “Baby.” Margalo Gillmore was just twenty-one years old when the lunches started, but she was already known to the Broadway regulars at the table. At the time, she was still living with her parents at 20 Beekman Place. Her mother had instructed her as a teen that when she couldn’t get home for lunch she should go nowhere else but the Algonquin, where the staff could look after her, and in the Twenties, Gillmore appeared regularly in shows just a few minutes’ walk from the hotel.

Gillmore was a third-generation actor; her parents and grandparents had spent many years on stages in England and America. Her parents, American actors Frank Gillmore and Laura MacGillivray, were on tour in England when Margalo was born on May 31, 1897, in London. The family returned to America two years later, and she grew up in a fourth-floor walk-up at 615 West 136th Street. As a child, all she ever thought about was performing: “I learned from it never to be late; when I walked to school I pretended I was on my way to a rehearsal. When I learned to read, I conquered the dull drudgery only because someday I might have a part in a play. At night in my bed I dreamed of my dressing room I might have one day.”

The childhood home of actress sisters Margalo and Ruth Gillmore, 615 West 136th Street. ◆ ◆ ◆

Her father helped to found the Actors’ Equity Association, and she was among the first union members to get a card. She made her Broadway debut in September 1917 in The Scrap of Paper, a three-act comedy based on stories from the Saturday Evening Post, at the Criterion Theatre, 1514 Broadway. Her first leading role came two years later in The Famous Mrs. Fair at Henry Miller’s Theatre, 124 West 43rd Street. The drama took place in New York and Long Island and ran for nearly two hundred performances. Gillmore’s star rose in 1922 when she starred in He Who Gets Slapped at the Garrick Theatre, 67 West 35th Street. One reviewer called Gillmore “the most interesting and the most promising young actress on the American stage.”

In 1935, approaching forty, she married Robert Ross, a Canadian actor-director five years her junior at her parents’ apartment at 31 Beekman Place. She and Ross played husband and wife onstage in 1953 in the hit Kind Sir, until he died in February the following year. Also in 1954 she played Mrs. Darling in Peter Pan, alongside Mary Martin, at the Winter Garden Theatre, 1634 Broadway. CBS telecast the show live to an audience of sixty-five million viewers. She performed the role of Mrs. Van Daan in the theatrical adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank, which ran from 1955 to 1957. Altogether, she made more than twenty-five motion picture and television appearances, but her most memorable role onscreen was as Grace Kelly’s mother in High Society, in 1956.

Jane Grant

Among her many gifts, Jane Grant had a beautiful singing voice and a head for business. Her vocal talents landed her a one-way ticket from Kansas to Manhattan, but her savvy writing and business skills made a lasting mark and gave readers one of the greatest magazines ever. She was the driving force behind the birth of The New Yorker, pushing her first husband, Harold Ross, to realize their dream of starting a magazine. “There would be no New Yorker today if it were not for her,” Ross said in 1945. “He would have given up, I am sure, if I hadn’t encouraged him,” Grant said after Ross’s death. “Fortunately I was able to influence him, for he was in love with me.”

Although she came from humble Midwest stock, Jeannette Cole Grant was destined to rub shoulders with the Manhattan elite. She was born on May 29, 1892, in Joplin, Missouri, to a farmer father and teacher mother. Her mother died when she was six, and the family moved to Girard, Kansas, to be close to her maternal relatives. She was a good student with a talent for singing, but young women in Girard at the time had only two paths in life: farmwife or schoolteacher. Young Jeanette wanted neither.

Jane Grant and Harold Ross, three years before they launched The New Yorker, outside their Hell’s Kitchen home at 412 West 47th Street. Over the decades Grant has been left out of the history of the magazine’s creation; however, Ross admitted that without her The New Yorker would never have gotten off the ground. ◆ ◆ ◆

She talked her family into allowing her to go to New York to take voice lessons for a year after she graduated from high school, after which she would return to Kansas to take up a teaching post. She had never been farther east than Kansas City when she took the 1,300-mile railroad journey to New York in 1908. She was just sixteen years old and lived in Roselle Park, New Jersey, a 25-mile train ride to Manhattan.

A couple of years later she moved into the Three Arts Club—a residence for young women studying drama, music, and fine art—at 340 West 85th Street. Several high-society women at the club took an interest in the girls and tried to plane their rough edges. One of them helped the farmer’s daughter transform herself into a smooth conversationalist and charming dinner guest. When her singing career didn’t take off, Grant enrolled in business school. In 1912 she took a clerical job at Collier’s Weekly. Two years later she landed a job at the Times answering phones in the society department for $10 a week. The paper’s legendary managing editor, Carl Van Anda, told her that while women were tolerated on the staff, there was no chance for advancement.

A newsroom darling, she taught the men to dance, and they taught her to gamble and curse. While there, Grant befriended a young Alexander Woollcott, a city-room reporter at the time. By 1915 she was covering events and writing her own stories for the paper, crossing from society department to city desk and becoming the first female general assignment reporter on the New York Times. Soon she was bouncing around town, from operas with Enrico Caruso to ballgames at the Polo Grounds. At the time, she lived in a rented room at 119 West 47th Street, not far from her future home with Ross, and then later, across the street from Carnegie Hall.

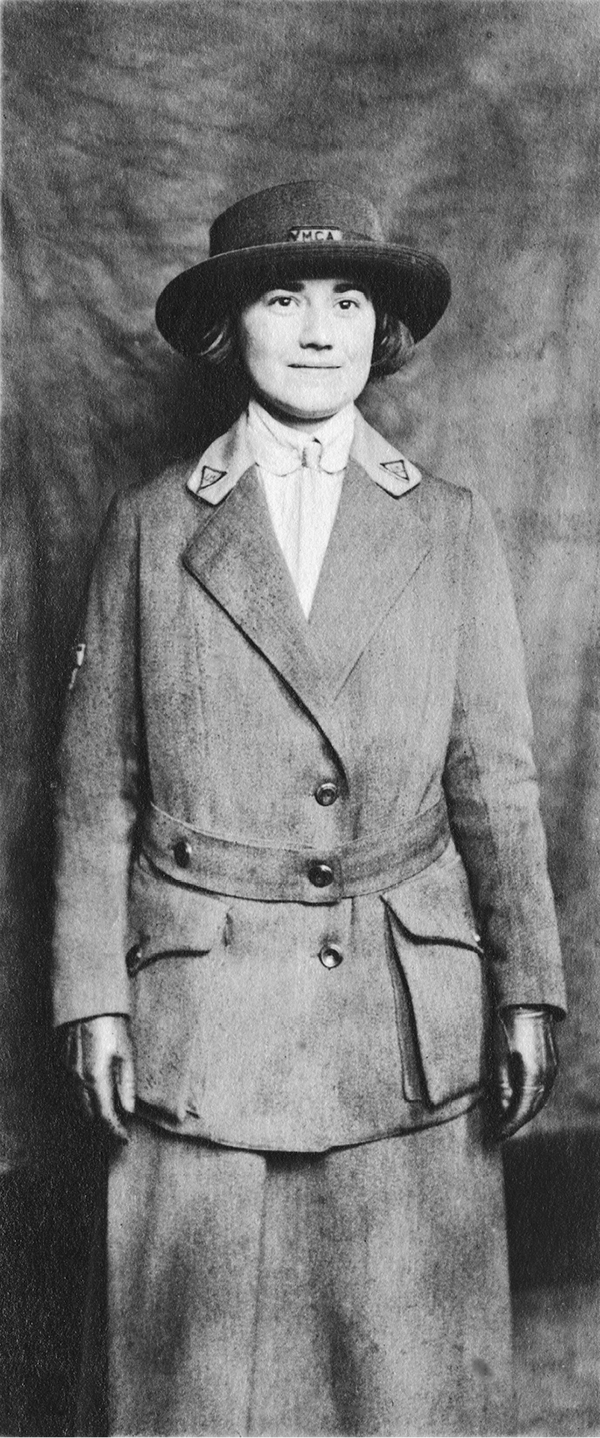

Jane Grant talked her way into the YMCA to go to France. ◆ ◆ ◆

When America entered the war, she begged to be sent as a correspondent. The paper refused her request. Seeing Woollcott volunteer and enlist in a hospital company doubled her determination, so she joined the YMCA, which was sending women over to help the troops by singing, setting up dances, and screening movies. She arrived in late 1918, earning $108 a month—more than the Times was paying her.

In France, Grant met many future Round Tablers. Woollcott introduced her to his Stars and Stripes editor, Harold Ross. The two dated briefly in Paris, but Grant had other suitors, and kept him at bay until the war ended. When she returned to New York in the summer of 1919, the Times promoted her to editor of hotel news. Ross and Grant married the next year, and briefly lived in the Algonquin Hotel. The couple rented a bedroom in the home of Broun and Hale for a summer. A year later, with close friend Ruth Hale, Grant cofounded the Lucy Stone League, a forerunner of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Its motto was: “My name is the symbol for my identity and must not be lost.” Maintaining her maiden name was a lifelong crusade.

In 1922 Ross and Grant bought an apartment building at 412 West 47th Street. Soon after, she pushed him to get their magazine idea off the ground. She helped pitch the proposal to investors and talked it up to her wide circle of friends and associates. Grant landed Ross an appointment with investor Raoul Fleischmann, who bankrolled the magazine. Grant should also take credit for launching Janet Flanner’s career. She met Flanner through Neysa McMein and showed Ross letters that Flanner wrote from Paris, urging him to hire her to write for the magazine. He did, calling her Genêt, which he thought was Janet in French. Flanner wrote her “Letter from Paris” for fifty years, earning her the US National Book Award.

When Grant’s marriage to Ross fell apart just three years after the magazine launched, she didn’t seek alimony. Instead, she wanted fair compensation for the hard work she had put into making the magazine a success. Ross agreed to $10,000 a year, to come from his own stock dividends. For the next twenty years, Grant chased down checks from her ex-husband.

After the divorce, Grant traveled the world and wrote freelance pieces. She became the first female Times reporter in China and Russia in the early Thirties, interviewing political leaders and the ordinary people she met, but neither the Times nor The New Yorker has ever paid proper tribute to her pioneering achievements.

Grant’s second marriage was to William B. Harris, an editor on Fortune, in June 1939. The couple bought land in Litchfield, Connecticut, named it White Flower Farm, and Grant began an entirely new chapter of her life.

James Abbe took this portrait of Ruth Hale when she was thirty-six. ◆ ◆ ◆

There was no bigger iconoclast sitting at the Round Table than Ruth Hale. The writer-publicist was married to Heywood Broun, but nobody dared call her Mrs. Broun. Hale was a writer, editor, and publicist, but she was most famous for her “fanatical” devotion to women’s rights in the Jazz Age. Hale was the driving force behind the Lucy Stone League, a group that supported married women keeping their maiden names legally.

Hale was Southern by birth, but she didn’t fit the stereotype of easygoing grace, charm, and humility. In fact, she took great pride in losing her Southern accent.

She was born in Rogersville, Tennessee, on July 5, 1886. Her father was an attorney and her mother, a high school mathematics teacher. When she was ten, her father died, and three years later Hale was sent to boarding school at the Hollins Institute (today, Hollins University) in Roanoke, Virginia. At age sixteen, she enrolled in the Drexel Academy of Fine Art (today Drexel University) in Philadelphia, with dreams of becoming an artist.

When Hale was eighteen years old she became a journalist in Washington, D.C., writing for the Hearst syndicate. She worked at the Washington Post briefly before returning in her twenties to Pennsylvania and the drama department of the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Hale also tried sportswriting decades before other women took it up.

Around 1915 Hale moved to New York and sold small pieces to the Times, the Tribune, and Condé Nast magazines. She took bit parts on Broadway and posed for artistic nude portraits for fashion photographer Nickolas Muray. She became a sought-after theatrical publicist and worked for the top producers.

Alice Duer Miller introduced Hale to Broun at a New York Giants baseball game at the Polo Grounds. They married in 1917. Hale begrudgingly accepted a traditional church wedding but refused to walk down the aisle until the organist ceased playing Mendelssohn’s “Wedding March.” When the war started, the newlyweds went to France as correspondents. After several months in Paris, Hale became pregnant. Returning to New York, the couple set up house at 333 West 85th Street. The unusual marriage had Hale on the first floor and Broun occupying the second.

In 1918 Hale gave birth to the couple’s only child, Heywood “Woodie” Broun III. (As an adult, Woodie took his mother’s name, and was known as sportscaster Heywood Hale Broun.) The couple led completely separate lives.

In 1921 she took a stand with the US State Department, demanding that she be issued a passport as Ruth Hale, not Mrs. Heywood Broun. The government refused; up until that time, no woman had ever been given a passport with her maiden name. She was unable to cut through the red tape, and the government issued her passport reading “Ruth Hale, also known as Mrs. Heywood Broun.” She refused to accept the passport and canceled her trip to France. So did her husband.

In May 1921 she was issued a New York City real estate deed in her own name—believed to be the first ever given to a married woman—for an apartment house on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Not long afterward, she was chosen president of the Lucy Stone League. Her husband was among the men present; other Lucy Stoners were F.P.A. and his second wife, Esther Root; Janet Flanner; Jane Grant; Beatrice Kaufman; and John Barrymore’s playwright wife, Michael Strange (Blanche Oelrichs). Hale made headlines in August 1927 when she took a leading role in protesting the executions of accused anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti, traveling to Boston for the unsuccessful defense committee.

In the Twenties, she worked as a theatrical press agent, reviewed books for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and ghost-wrote many of Broun’s columns. In 1925 she became one of the earliest contributors to The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town.” About the time the Round Table ran out of steam, so did Hale. She moved out of New York to a ramshackle farmhouse, called Sabine Farm, in Stamford, Connecticut.

As the Twenties ended, Hale spent considerable time fighting for women’s rights and less time in journalism. Hale and Broun were quietly divorced in Nogales, Mexico, in November 1933.

Beatrice Kaufman

One of the most beloved women in the group was Beatrice Kaufman. ◆ ◆ ◆

The Vicious Circle rarely tolerated wives. Alexander Woollcott, de facto ruler of the table, allowed Beatrice Kaufman to attend partly because of his loyalty to her husband, George. But Beatrice knew she couldn’t remain an unemployed woman in their midst, nor did she live in the shadow of her famous playwright husband. She carved out her own identity, working in Broadway publicity, and later taking a job as a reader for publisher Horace Liveright.

Beatrice Bakrow was born on January 20, 1895, in Rochester, New York, to middle-class parents in the textile business. She was tall, heavy, and not very attractive, but she made up for it by being funny, charming, stylish, and a good conversationalist. She studied briefly at Wellesley, but was kicked out freshman year for breaking curfew.

In the summer of 1916, during a party for her cousin Allan Friedlich and his new wife, Ruth Kaufman, she met the bride’s younger brother, George, a backup drama critic on the New York Times making $36 a week. Shy, quiet, and withdrawn, the reporter hit it off with the funny girl; she talked, and he listened. The two couples visited Niagara Falls together, and the next day Beatrice announced to her family that she and George were getting married.

They wed in March 1917 in Rochester, with F.P.A. as best man and no money for a honeymoon. The couple had an unusual twenty-eight-year marriage. Not long after their wedding, Beatrice miscarried. It devastated the couple, but George took it to another level. He couldn’t bear to have a sexual relationship with his wife, and never did again. From then on, they had an open marriage while maintaining the outward appearance of a normally married couple. When George found himself in a national sex scandal with actress Mary Astor in 1936, Beatrice stood by him even as the press chased her husband across the country. For his part, he always had her read his plays before anyone else.

Her husband’s tawdry 1936 sex scandal forced Beatrice Kaufman into the spotlight. ◆ ◆ ◆

In the span of a few years she reinvented herself as a society woman, appearing in gossip columns for hosting charity events and gala parties. When the Round Table began, the couple lived at 241 West 101st Street. By 1920 they had relocated a mile south, to 150 West 80th Street. Five years later they rented an apartment at 200 West 58th Street. They also lived for a time in the Hotel Majestic, on the corner of West 72nd Street and Central Park West. In 1934, when her husband was among the best-paid men on Broadway, the Kaufmans lived at 14 East 94th Street.

One of Bea Kaufman’s closest friends on the Round Table was Margaret “Peggy” Leech. In 1934 the pair went to Jamaica to work up a play they hoped to stage. Their only Broadway show, Divided by Three, tells the story of a middle-aged woman who falls in love with another man but who won’t leave her husband. The play opened in the Ethel Barrymore Theatre but received tepid reviews, despite starring Judith Anderson and Hedda Hopper. It also had the poor luck to open the same week as a play penned by her husband and Moss Hart, Merrily We Roll Along, a much bigger hit. Divided by Three only lasted a month.

In February 1936, Carmel Snow hired Beatrice as the Harper’s Bazaar fiction editor. Later that year, Samuel Goldwyn contracted for her services as a script reader and story editor for his movie studio. As World War II began, the Kaufmans were wealthy celebrities worthy of a splashy pictorial in Life with Moss Hart and Harpo Marx.

George S. Kaufman

George S. Kaufman influenced playwrights such as Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, and Neil Simon. ◆ ◆ ◆

At every stage of George S. Kaufman’s career was a member of the Round Table. Frank Adams gave the Pittsburgh native his first break by including him in “The Conning Tower” and securing a job for him at the Tribune. He wrote his first hit show, Dulcy, with Marc Connelly, and also collaborated with Aleck Woollcott, Edna Ferber, and Ring Lardner. Kaufman stayed active as a playwright, editor, producer, director, and actor in New York for more than forty years. He wrote or cowrote forty-five plays (more than half of them hits). He and Morrie Ryskind won the 1932 Pulitzer for Of Thee I Sing, and Kaufman won the 1937 prize with Moss Hart for You Can’t Take It with You.

Kaufman was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1889. He wasn’t given a middle name at birth. To mimic Franklin P. Adams, who also had adopted a middle initial, Kaufman chose “S” so that he too would have three letters in “The Conning Tower,” as G.S.K. (later, he claimed, for Simon). Kaufman married Beatrice Bakrow in 1917. They adopted a daughter, Anne, in 1925, and lived at 158 West 58th Street before moving to 14 East 94th Street.

On their fifth wedding anniversary, Woollcott sent a telegram to the Kaufmans: i have been looking around for an appropriate wooden gift and am pleased hereby to present you with elsie ferguson’s performance in her new play.

Kaufman once slipped out of a theater during the performance of one of his shows to send a telegram to an actor in the cast that read: i am watching your performance from the last row. wish you were here. His comebacks were equally legendary. An actress told him that she had trained her dog to curl himself around her neck and remain motionless while she entered hotel lobbies, as a sort of living fur neckpiece. “I taught my dog the trick for a special reason,” she told Kaufman. “Hotels are silly enough to keep dogs out entirely. Now that my Fido can look so much like a fur piece, I can smuggle him into all the hotels on earth.”

“And how do you get in yourself?” he asked.

In public, Kaufman avoided off-color humor, but in private he and his wife had an open marriage that allowed for discreet indiscretions and, in George’s case, a charge account at Polly Adler’s brothel. In the summer of 1936, Kaufman’s name hit front pages from coast to coast. Actress Mary Astor was embroiled in a child custody case with her husband, and her diary was leaked to the press. “We saw every show in town,” she wrote. “Had grand fun together and went frequently to 73rd Street where he fucked the living daylights out of me.” A court subpoena sent Kaufman to hide out at Moss Hart’s house. Even afterward, Kaufman was astonished to see himself portrayed as a sexual dynamo:

I can’t understand why there should have been so much public interest in the case. The public doesn’t care about writers. Miss Astor is no longer a big figure in pictures. I just can’t understand it. . . . There is one thing I resent about the case. Some newspapermen referred to me as a middle-aged playwright. I am middle-aged. That’s why I didn’t like it, I suspect.

Four years after Beatrice died, Kaufman married Leueen MacGrath, a ravishing blonde English actress twenty-five years his junior. Kaufman was her third husband, and they lived at 410 Park Avenue.

Margaret Leech

Margaret Leech wrote short stories and novels before becoming a dedicated presidential historian. ◆ ◆ ◆

Of the five members of the Round Table to win a Pulitzer Prize, Margaret Leech received the honor twice. She was one of the least known of the famous group, but among its members she was the most loyal friend.

Born on November 7, 1893, in Newburgh, New York, Leech graduated from Vassar in 1915 before gravitating toward a writing career that began with Condé Nast’s magazines. In 1920 she lived at 315 West 79th Street with her parents, and later at 315 West 97th Street. Leech wrote a handful of articles for The New Yorker, including several profiles of women newsmakers. She dabbled in stage acting but never pursued it seriously. Her nickname at the Vicious Circle was “Peaches and Cream” for her wholesome good looks and demeanor.

In the Twenties, Peggy Leech rented an apartment at 36 West 12th Street, near Washington Square Park. ◆ ◆ ◆

In her thirties she wrote two novels, The Back of the Book (1924) and Tin Wedding (1926), both receiving strong reviews. At the time she was living at 36 West 12th Street. In 1927 she collaborated with Heywood Broun on a biography of postal inspector Anthony Comstock, who in 1873 had founded the infamous New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Written in the era of enforced censorship and speakeasy raids, Anthony Comstock: Roundsman of the Lord’s subject matter seemed eerily relevant once again. It was Leech’s first book of nonfiction. Broun and Leech wrote alternating chapters, but their partnership had its challenges: One story has it that when Leech went to Broun’s house to pick up the manuscript, he couldn’t find it in his messy room. Nevertheless, the book was a critical and commercial success, and the first Book of the Month pick.

In 1928 she wrote her last novel, The Feathered Nest, before turning entirely to nonfiction. She also worked as a correspondent for the World. The next year, Harper’s published her short story “Manicure,” a tale of adultery that became a sensation and found a place in The Best Stories of 1929, a collection that also included Willa Cather.

In August 1928, Leech married Ralph Pulitzer—eldest son of publisher Joseph, president and editor of the World, and a divorcé with two grown sons—at the Community Church of New York, 40 East 35th Street. Reverend John H. Holmes, one of the most famous religious leaders in the nation, officiated at the ceremony. They resided first at 450 East 52nd Street (with eight servants) before moving to their permanent home at 120 East End Avenue. The couple had two daughters: Margaretta, who died at the age of sixteen months while the couple was vacationing in St.-Jean-de-Luz, France, and Susan, born in 1932.

Ralph Pulitzer suffered the enmity of many journalists for closing and selling the World in 1931. He and his wife traveled the world so he could pursue big-game hunting in Central America, West Africa, and India. He died following abdominal surgery on June 14, 1939; she never remarried.

After the death of her husband, Leech devoted herself to writing full-time. She commuted from New York to Washington for five years to work on Reveille in Washington: 1860–1865, earning the ire of the War Department by asking to see files on spies arrested during the Civil War. When the government refused to grant her access, she said: “What do you think I might do with the Secret Service reports of 1862? Sell them to the Japanese?” Published in 1941, the book won the Pulitzer for history and earned her such regard that Newburgh offered to hold a Margaret Leech Day. “I shall ride back and forth under the triumphal arch all afternoon, if they have a triumphal arch,” she joked. Some questioned the fairness of an author winning a prize named for her father-in-law, but Time magazine praised the book’s fine writing and proclaimed that she had earned the award “with no hint of nepotism.” Civil War historians still consider it a classic text.

Eighteen years later, she won her second Pulitzer for In the Days of William McKinley, published in 1959. She was the first woman to win the prize for history, and she remains the only woman to have won it twice. In the Days of McKinley also earned her a National Book Award and Columbia University’s Bancroft Prize in American History. As a widow raising her surviving daughter, Susan, Leech lived in Gracie Square and in Lenox, Massachusetts, the cultural heart of the Berkshires. Leech told an interviewer that her apartment had two bathtubs: one for bathing, the other to store her notebooks while writing. Her closest friends within the Vicious Circle were Ferber and McMein.

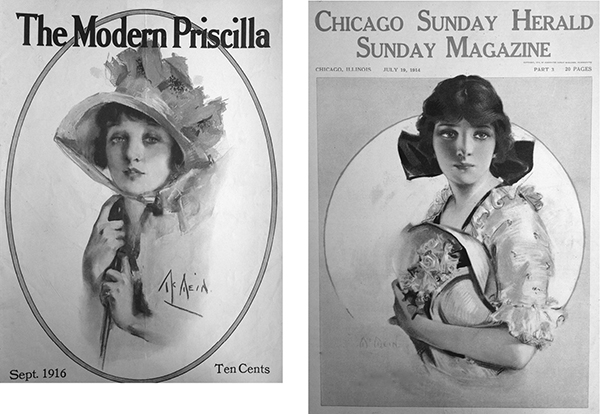

Neysa McMein

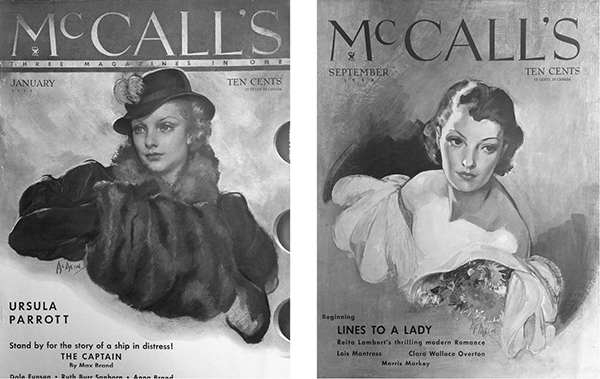

Marc Connelly fondly recalled Neysa McMein as the woman who “rode elephants in circus parades and dashed from her studio to follow passing fire engines.” She held sway over the group, which was drawn to her larger-than-life personality and charisma. For twenty years, she was the most famous female artist in the country. Her distinctive, colorful covers helped sell millions of magazines. In 1929 she was called “the highest-paid woman artist in the United States.”

In today’s money, McMein earned about a quarter of a million dollars annually for her cover illustrations. She was also in demand for advertising campaigns for beauty, healthcare, and luxury products. ◆ ◆ ◆

Marjorie Moran McMein was born on January 25, 1888, in Quincy, Illinois, and after attaining fame she returned there as a celebrity but once. She studied at the Chicago Institute, and broke into advertising in her early twenties by drawing shoes and hats in the Second City. She knew that New York would be a better market for her, however, so in 1912 she moved east. When she arrived at the train station, her new name was Neysa.

McMein’s painting studio became a salon for the Round Table. She could paint in the midst of cocktail parties. ◆ ◆ ◆

She set up a studio in a commercial building at 57 West 57th Street. Wearing pearls and a paint-smeared smock, the professional artist with a zest for life painted beautiful models for magazines that included McCall’s and the Saturday Evening Post, and for ads by companies that included Palmolive and Wrigley’s. While the model (sometimes a showgirl spotted on the sidewalk) posed, a party went on around them in the studio. The Algonquin crowd gravitated to McMein’s after their luncheons. A visitor might see Harpo Marx clowning for Alexander Woollcott and Charles MacArthur. Cole Porter sang to Neysa while she worked; George Gershwin pounded McMein’s piano. Dorothy Parker and her first husband, Edwin Pond Parker II, lived across the hall. Tallulah Bankhead, Marc Connelly, and Ruth Gordon stopped by. In 1924, Edna Ferber fashioned McMein into Dallas O’Mara in the Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, So Big.

Before radio and television, McMein could announce who she believed were the most beautiful women in the country, and it made headlines. She wrote magazine articles about beauty and fashion, and later a syndicated newspaper column devoted to her other passions, numerology and party games. She also teamed up with Parker: McMein would paint a portrait of a president or a prizefighter, and Parker would write an account of the sitting.

McMein lived in a brownstone at 136 West 65th Street in 1918; the building was demolished about forty years later to make way for Lincoln Center. In 1920 she lived half a block from Madison Square Park, at 226 Fifth Avenue.

In June 1923 she secretly married John Baragawanath, a mining engineer, but business kept him from going on their honeymoon to Europe. McMein informed Woollcott, whose response was to sail with her on the Olympic; Marc Connelly and violinist Jascha Heifetz tagged along. The press reported that McMein was on her honeymoon in France with three men, none of them her husband.

In December 1924, her only child, Joan, was born. The family moved to 29 East 64th Street, where the couple hosted the wedding of Arthur Samuels and actress Vivian Martin in February 1926. McMein and her family later moved to a duplex at 131 East 66th Street, her last address.

Herman Mankiewicz

Mankiewicz worked for newspapers and magazines before going to Hollywood and writing Citizen Kane. ◆ ◆ ◆

Without Herman Jacob Mankiewicz we wouldn’t have Citizen Kane or Animal Crackers. He had a career like nobody else in the Vicious Circle. As a press agent, he worked with heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey. At the New York Times, he worked under George S. Kaufman. When Harold Ross launched The New Yorker, he tapped “Mank” as a critic. When the Marx Brothers wanted to make movies, he produced them. But it was Mankiewicz’s experiences in New York City and Hollywood in the Twenties that inspired him to write his masterpiece, winning the Academy Award for the screenplay of Citizen Kane in 1941 with Orson Welles.

A native New Yorker, Mankiewicz was born on November 7, 1897. His father was a teacher and his mother a dressmaker, both German immigrants. When Mankiewicz was a boy the family moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he grew up. He transferred his boyhood to the screen in Citizen Kane; the famous “Rosebud” was actually his stolen childhood bicycle. Mankiewicz was a brilliant student, admitted to Columbia when he was just fifteen years old. He earned his philosophy degree in three years and then attended graduate school. At the time he lived in the East Village at 44 St. Mark’s Place.

When World War I broke out, Mankiewicz enlisted in the US Marine Corps and shipped out to France, where his fluent German served him well. After the war, he married his sweetheart, Sara Aaronson, in Washington, D.C. The couple returned to postwar Berlin, where Mankiewicz worked for the Red Cross and, later, as a correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. He didn’t come to New York until 1922, when the Vicious Circle was already an institution. Mankiewicz went to work at the World, where he met Broun and F.P.A. A year later, he moved to the Times.

Kaufman took Mankiewicz to the Algonquin for the first time. He passed the test and was allowed to come to the table whenever he liked, usually once a week. Although Mankiewicz wasn’t a member of the original group, he quickly fit in. Woollcott called him “the funniest man in New York.” Sherwood said he was “the truest wit of all,” and Pemberton considered him “the one real wit” at the table. Mank reveled in the Vicious Circle: He drank with Dorothy Parker and Ring Lardner; F.P.A. was his poker buddy; and Harold Ross leaned on him. At lunch one afternoon, Mankiewicz turned serious and announced to the group, “I have a new baby boy, born today. His name is Frank.” To which Marc Connelly replied, “Does Sara know?”

In 1926, as the Round Table was winding down, Mankiewicz went to Hollywood to pursue screenwriting. He ultimately worked on more than seventy films, both silent and talkies. From 1931 to 1933 he worked as a producer on three Marx Brothers films in a row: Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, and Duck Soup. He bounced from studio to studio, but as the Thirties drew to a close the planets aligned and Mankiewicz found himself working with Orson Welles. After one of his numerous crack-ups, Mankiewicz was laid up at home on bed rest. Welles visited the screenwriter daily, and Citizen Kane, based on Mankiewicz’s childhood in Pennsylvania and journalism career in New York, took shape. The film today is remembered as Welles’s masterpiece, but without Mankiewicz as the dream catcher, it wouldn’t exist. Unfortunately, winning an Academy Award didn’t help Mankiewicz’s career, and he spent the next twenty years battling alcohol and gambling addictions.

Harpo Marx

Harpo (Arthur), Gummo (Milton), Chico (Leonard), and in front, Groucho (Julius) Marx, about 1924. ◆ ◆ ◆

As a member of the Marx Brothers, Harpo Marx said nothing, and in doing so he often said more than the rest. Wearing a large, fuzzy wig—blond, pink, or scarlet by various accounts—with a moon face, large wide eyes, and a raincoat flapping open, Harpo was unforgettable. He made rapid gestures, wild expressions, and chased girls with his automobile horn. He taught himself to play his trademark harp by ear.

Marx wasn’t an original member of the Round Table. He and his brothers had broken into the upper echelons of vaudeville in the years following World War I, and in 1924 they made their Broadway debut in I’ll Say She Is at the Casino Theatre, formerly at 1404 Broadway. Woollcott stumbled upon the revue and was thunderstruck, telling his friends and readers that the Marx Brothers were in a hit. Woollcott called Harpo “the funniest man I have ever seen on the stage.”

Adolph (later Arthur) Marx was born on November 23, 1888, in a tenement apartment in Yorkville to an Alsatian tailor. His mother, Minnie, was a singer. At P.S. 86, he made it as far as the second grade. Their mother pushed him and brothers Julius (Groucho), Leonard (Chico), Milton (Gummo), and Herbert (Zeppo) into saloons and dirty theaters from Coney Island to Manhattan as they developed their act. With their mother rounding out the group, they were known as the Six Musical Mascots; later they performed as the Three Nightingales, then Four. The brothers took their act on the vaudeville circuit for close to a decade before becoming famous.

On the road in Illinois in May 1914, the four brothers gathered around a poker table with vaudeville comedian Art Fisher, who gave them the names by which we know them. They sat down as Leonard, Arthur, Julius, and Milton, and stood up as Chico, Harpo, Groucho, and Gummo: Chico, because he chased girls, or chicks (the correct way to pronounce his nickname); Harpo, for his instrument; Groucho, because he always carried his grouch bag around his neck to collect tips; and Gummo, because he wore gum-soled shoes as the team’s dancer.

Harpo lived with ten family members in a small apartment at 179 East 93rd Street. By 1918, the same year the brothers played The Palace, he was living down the road at 15 East 93rd Street, near Central Park.

At the Algonquin, Harpo was able to drop his act.

The Marx Brothers grew up in the German-Jewish section of the Upper East Side. Today a nearby playground is named in their honor. ◆ ◆ ◆

An immediate fan, Broun saw the Marx Brothers more than thirty times, worrying that his obituary would say that moving scenery in a Marx Brothers show had killed him. But the best acquaintance Harpo made at the Table was George S. Kaufman, who convinced the brothers to let him script a show. He eventually wrote Animal Crackers and A Night at the Opera.

In September 1936, Harpo married Susan Fleming, a former Follies dancer—nickname: “The Million-Dollar Legs”—from Forest Hills, Queens. They adopted four children.

Harpo was a blithe spirit. At dinner one night, seated next to Kaufman, the playwright noticed that Harpo’s watch erroneously read 12:20. “I haven’t wound it in three years,” Harpo said with a smile. “It doesn’t matter to me what time it is.”

In 2003, the New York Parks Department named a neighborhood playground at Second Avenue and East 96th Street in honor of the Marx Brothers.

The cipher at the Round Table and the person who has fallen deepest into the cracks of the group’s shared history is William B. Murray. He isn’t remembered for anything today, although he was the one who sent out Pemberton’s invitations to the first lunch, according to Margaret Case, and Murray’s first wife had a forty-year romance with Janet Flanner of The New Yorker.

Actress Ilka Chase and husband William B. Murray at the Waldorf Astoria New York, 1941. ◆ ◆ ◆

Murray was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, on December 9, 1889, raised in Brooklyn, and graduated from Cornell. He worked as music critic for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from 1918 to 1923, meeting Alexander Woollcott at the theaters and becoming friendly with publicists John Peter Toohey and Murdock Pemberton. He loved playing the chimes at Trinity Church on Wall Street. He was so popular that in 1921, Edison Records released a recording of him performing “Joy to the World” and “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” That year he was living at 38 West 40th Street.

In the Twenties, Murray switched from journalism to publicity, marketing grand pianos for the Baldwin Piano Company. In his role as concert manager he traveled to Europe, seeking concert artists to perform back in the States. In the summer of 1922, while in Rome on business, he met Natalia Danesi, a raven-haired Italian opera singer. The following year she came to New York, and in 1924 the couple married at Trinity Church, with Woollcott as best man. The couple had a rocky relationship and one son, William Jr., born in 1926. Danesi promptly took the boy back to Italy.

In December 1928, on the recommendation of Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, King Victor Emmanuel III awarded the Chevalier’s Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy to Murray, whose sole qualification appears to be that he married an Italian.

In September 1934, Danesi sued for divorce, granted later that year. Murray married actress Ilka Chase, a divorcée fifteen years his junior, the following year. They moved to 333 East 57th Street, and their marriage lasted eleven years. After World War II Murray married an interior decorator, Florence Smolen, with whom he had twin boys.

As the city’s premier talent agent, he rose to become the head of the radio department of the powerful William Morris Agency (office at 1270 Sixth Avenue). His clients included Fred Allen, Fanny Brice, Eddie Cantor, Al Jolson, and Groucho Marx. As head of the department, he created advertiser-supported shows for Abbott and Costello, Burns and Allen, and Amos and Andy, among others. One of his last projects was with client Milton Berle; in 1948 the comedian’s Texaco Star Theatre was among the first hit TV series when the medium was born.

The poster girl for the Round Table has always been Dorothy Parker, a distinction she loathed for the rest of her life.

Born August 22, 1893, in West End, New Jersey, at her parents’ summer beach cottage, Dorothy Rothschild grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Her mother died just before her fifth birthday, followed by her stepmother, before she turned ten.

Dottie rhymed sentences at a young age. In 1906, during a summer vacation in Bellport, on Long Island, she sent a postcard to her father and the family dog:

Dorothy Parker—painted here by Neysa McMein—joined Vogue at age twenty-one, launching her career. ◆ ◆ ◆

Dear Papa,

We are all well,

the same to you.

My love to Rags,

and now I’m through.

Dorothy

The aspiring poet was twenty years old when her father died at their home, 310 West 80th Street. She spent the next year working odd jobs and writing verse. The first person to notice her talent was Frank Crowninshield, editor of Vanity Fair. He accepted her first piece of light verse, “Any Porch,” for the September 1915 issue, for $5. Emboldened by its acceptance, she marched down to the company’s offices at 19–25 West 44th Street and asked for a job. She ultimately landed work for the company’s sister publication, Vogue, under Edna Woolman Chase, who recalled:

In 1915 a small, dark-haired pixie, treacle-sweet of tongue but vinegar-witted, joined our staff. Her name was Dorothy Rothschild, and she was engaged to do captions and special features. She wrote a piece about houses called “Interior Desecration,” and more than one decorator swallowed hard and counted ten before expressing his feelings about it. Showing rare courage, she risked her head in the line of duty and turned in her experience under the title “Life on a Permanent Wave” when the wave was still a hazard and its most permanent aspect was the entire day required to accomplish it.

In 1917 Dorothy married Edwin Pond Parker II, a stockbroker. He enlisted in the army ambulance corps and soon was bound for France. Meanwhile, Parker migrated to Vanity Fair, taking up the drama critic job vacated by P. G. Wodehouse. In her legendary columns, she lambasted casts and audiences alike with vim and vigor, and she had no qualms about stepping on the toes of the powerful. It was hard to miss Vanity Fair’s representative on Broadway.

When the Round Table began in 1919, Parker was already friendly with many of the group’s members. She knew Broun through her older sister, Helen. Frank Adams ran many of her poems in his column. Woollcott was a friend from Broadway first nights. Robert Benchley and Robert E. Sherwood were coworkers. The next year, following her split from her husband, she lived alone at 235 West 71st Street. Donald Ogden Stewart met Parker at this time at the Life magazine office: “Dorothy was sort of a roving imp-at-large. She was absolutely devastating: petite, graceful, black bobbed hair, keen startling eyes.”

During the Round Table’s reign, Parker’s legend grew to enormous proportions. Newspapers ran her words on a constant basis, and she was quoted across the country. Cole Porter even wrote her into a hit song. With her fame spreading, she became a personality. But she also had become a gifted short-story writer. She contributed some of the first short stories to The New Yorker in its formative years, including the classics “Arrangement in Black and White” and “Dusk before Fireworks.” In 1929 the semiautobiographical “Big Blonde” won the O. Henry award for best story.

In the Thirties, she took up screenwriting, which she hated, and left-wing causes, which she loved. She and her second husband, Alan Campbell, became a hot screenwriting partnership in 1934, the year of their first marriage. In Hollywood, Parker jumped into the political scene with numerous causes, benefits, and campaigns. Her activities drew the attention of the FBI, which created a 300-page dossier on her. During World War II, she shuttled between rented mansions in Beverly Hills and a country house in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. A reporter once asked Parker to describe her house in two words. “Want it?” was her reply.

Parker spent the Forties and Fifties writing short stories for magazines, the occasional screenplay, and giving a lot of her time to political causes. In 1946 she and Campbell split, and Parker spent a few years with a young writer, Ross Evans. When that relationship ended, she and Campbell remarried in 1950. They had just enough screenwriting jobs to scrape by in West Hollywood in the Fifties, but when times were bleak the couple went to the state unemployment office together.

A few minutes after this photo was taken, Dorothy Parker was arrested outside the Massachusetts Statehouse for protesting the planned execution of anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti. ◆ ◆ ◆

It sounds like the plot to one of his Broadway hits: Hick conquers metropolis. But it really did happen that way. Brock Pemberton went from Kansas newspaperman to powerful Broadway producer, and became the father of the Tony Awards.

As a young Broadway producer, Brock Pemberton had several hits. ◆ ◆ ◆

Ralph Brock Pemberton was born on December 14, 1885, in Leavenworth and grew up in Emporia, Kansas, where his father worked as a salesman. William Allen White, legendary editor of the Emporia Gazette, had known him since he was a boy, and, after Pemberton graduated from the University of Kansas, White hired him as a reporter. A dynamo on the tiny staff, Pemberton thrived under White’s tutelage. The elder newspaperman had earned a national reputation for his provocative editorials, and, in the age-old way of newspaper employment, he spoke to a New York City editor on Pemberton’s behalf. Young Pemberton booked a one-way ticket for Manhattan in 1910 and, after a 1,300-mile train trek, arrived on Newspaper Row to find that the position wasn’t going to materialize. But as luck had it, someone gave him a note to hand to Franklin P. Adams, who was on the Evening Mail at the time. Just as F.P.A. would later stick out his neck for Benchley and Kaufman, he also got a job for Pemberton as a reporter.

After a few months Pemberton transferred to the drama department at the Mail. For his first assignment, he innocently reviewed a musical called Everywoman at the old Herald Square Theatre as if he were in Emporia rather than Gotham. The staff found his hayseed review backslappingly funny, and the edition became a collector’s item—much to Pemberton’s chagrin.

In 1911 he moved to the World drama desk, where he got to know the bustling theater business intimately. A few years later he was offered the assistant drama editor position at the Times, working under Woollcott, the paper’s chief drama critic. In 1915, Pemberton married Margaret McCoy (who later worked as a costumer on her husband’s shows). In 1917, producer Arthur Hopkins—one of the most successful theater bosses in the city—offered him a different kind of job. In his new career, Pemberton worked in every capacity, from set construction to directing.

Pemberton stayed with Hopkins for just three years, but he learned all the skills a producer needs. When Hopkins passed on a three-act comedy called Enter Madame, Pemberton asked to produce it. He directed it as well, taking the biggest gamble of his life, which paid off. The show ran for two years at the Garrick, and he became a newly minted Broadway producer at the age of thirty-five. Soon after, Pemberton tapped Zona Gale to adapt her bestseller Miss Lulu Bett into a play, which opened just after Christmas 1920. A smash success at the Belmont, the production won the Pulitzer for drama the following year.

Brock Pemberton’s East 51st Street apartment overlooks the East River. ◆ ◆ ◆

When the Round Table began, Pemberton and his wife were living at 123 East 53rd Street in a building since demolished. In 1922, the offices of Pemberton Productions were at 224 West 47th Street. For a dozen years the couple lived at 115 East 53rd Street, but during World War II they moved to a grand Turtle Bay apartment in the Beekman Terrace at 455 East 51st Street.

Pemberton carved out a thirty-year career in the theater business. He took on risky shows and had many hits and several flops. He brought out the first plays by Maxwell Anderson and Sidney Howard. He launched the stage careers of Claudette Colbert, Miriam Hopkins, Walter Huston, Fredric March, and more. In 1928 he lost $40,000 on a show but bounced back the following year with the light comedy Strictly Dishonorable, which began a long association with actress-director Antoinette Perry. The pair had a string of hits, and backstage gossip hinted that they also had a long-running romantic relationship. In 1939, Pemberton and Perry were among those who helped to form the American Theatre Wing, which put on the Stage Door Canteen shows for servicemen during World War II. After Perry’s death in 1946, Pemberton pushed for the creation of the American Theatre Wing’s Antoinette Perry Awards for Excellence in Theatre—the Tony Awards.

Murdock Pemberton

Without Murdock Pemberton, the Algonquin Round Table wouldn’t have existed. The group may have lunched elsewhere—the Astor or the Knickerbocker—but it was Murdock’s decision to go to the Algonquin in 1919.

Pemberton took John Peter Toohey and Alexander Woollcott to the hotel and kicked off the daily gatherings. There he became close friends with Harold Ross. When The New Yorker launched in 1925, Pemberton started a thirty-six-year association with the publication, beginning with writing advertising copy. Then came light verse, thirty years of “Talk of the Town” pieces, as well as fiction, essays, and reporting. He was the magazine’s first art critic, and he gained national fame for being an everyman in the art world.

Over the years, Murdock Pemberton’s role in launching the Round Table has been overlooked. ◆ ◆ ◆

Murdock Albert Pemberton was born on April 6, 1888, in Emporia, Kansas, two years younger than Brock, and the youngest of their parents’ four children. The Pemberton brothers became so famous that when their mother died in 1937, the Associated Press published an obituary of her that appeared in newspapers across the country.

In 1910 both brothers worked for Emporia Gazette editor William Allen White. Murdock left Emporia for stints on the Kansas City Star and Philadelphia North American. When Brock moved to New York, his younger brother followed. Brock stayed in journalism for a little while, but Murdock immediately fell in love with the theater and became a publicity man. By 1912 his name was making the society pages.

In April 1916, Pemberton married Helen K. Tower at St. Luke’s Episcopal at 285 Convent Avenue in Hamilton Heights. Woollcott—who seems to have been a member of everyone’s wedding party—served as one of the ushers. The newlyweds soon had two children, Katherine and Murdock Jr. Providing for his family kept Pemberton out of the war, and in June 1917 he was a publicity agent for Charles Dillingham at the Hippodrome Theatre. Pemberton was also a genius for getting the theater into the papers. In 1919 when the Round Table started meeting, Pemberton was living at 777 Lexington Avenue.

Sculptures by Alexander Calder. Early in his career, Murdock Pemberton wrote, “Here is a young man who will go far.” Calder gave him a mobile. ◆ ◆ ◆

He took to wearing wild, sometimes checked shirts. His unorthodox sartorial decisions invariably got him press. “Murdock Pemberton has not worn a white shirt in ten years,” wrote O. O. McIntyre in 1938. “The gaudier the better.” Harold Ross appointed him The New Yorker’s first art critic, and in that capacity he championed modern art, becoming friendly with scores of first-rate artists, including Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi.

A little more than a dozen years after marrying Helen Tower, he left her and their children and moved to 671 Lexington Avenue with his mistress, Frances Mahan, an actress-dancer from the Hippodrome who was twenty years his junior. In 1936, the new couple lived at 55 West 46th Street before moving to 500 West 112th Street, across from the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Pemberton joined the mid-century exodus from the city, renting the ramshackle house on Ruth Hale’s Sabine Farm in Stamford, Connecticut. There he built an art studio, became a “Sunday painter,” and got Broun into painting.

In 1947 Pemberton returned to Emporia for the first time in twenty years for The New Yorker. His report, under “Our Far-Flung Correspondents,” detailed the local beef, martinis, and gossip. Pemberton continued writing professionally until the Sixties, when he fell on hard times.

In life, Harold Ross was always something of a mystery to his friends and the public. He started his career as an itinerant newspaperman, bouncing from one end of the country to the other and cultivating a reputation as a roustabout and loose cannon. But in his thirties, when The New Yorker went from the brink of cancellation to cultural zeitgeist, he didn’t take advantage of his newfound celebrity; he stayed in the shadows. Nonetheless, he had an outsize personality and almost cartoonish mannerisms. Janet Flanner described him as

an eccentric, impressive man to look at or listen to, a big-boned Westerner from Colorado who talked in windy gusts that gave a sense of fresh weather to his conversation. His face was homely, with a pendant lower lip; his teeth were far apart, and when I first knew him, after the First World War, he wore his butternut-colored thick hair in a high, stiff pompadour, like some wild gamecock’s crest.

Ross was born in Aspen, Colorado, on November 6, 1892. His father, an immigrant from Northern Ireland, worked as an engineer in the local silver mines. When he was a boy, the family moved to Salt Lake City, where he joined the West High School newspaper and fell in love with journalism. He dropped out to work on the Telegram, the city newspaper, getting hooked on police stations, saloons, and house fires. His father now ran a demolition business and wanted his son to work for him, but young Ross knew what he wanted: At the age of eighteen, he left home to become a freelance tramp reporter.

Ross took up drinking, chain-smoking, bad food, poker, and the hard life of a roving reporter with gusto. He worked from San Francisco to New Orleans, and even to the outskirts of New York City. He did stints on papers in Atlanta and Sacramento, and as hostilities in Europe dominated the headlines, Ross watched with interest. When America entered the war, Ross rushed to enlist in early 1917. He and his fellow soldiers in an engineering regiment were sent to Bordeaux as construction workers. There he realized that instead of fighting the Kaiser’s men, he was going to be digging ditches. When he found out that the army was starting a newspaper for the troops, he legged it to Paris. Ross soon joined the staff of Stars and Stripes, and the sloppy-looking private who never polished his boots fit right in.

For the duration of the war, Ross served as a journalist. The staff picked the twenty-five-year-old to be the editor, giving him his first taste of being the boss. The paper was a hit with the troops and even turned a profit, which went to the US Treasury after the war. On the staff, Ross met two men who would play a big part in his future: Captain Franklin P. Adams and Sergeant Alexander Woollcott. Adams was on the staff only for a short period, but they became lifelong friends. Woollcott had a sticky personality, and he and Ross developed a begrudging friendship that lasted for more than two decades. The most important person whom Ross met in France, however, was Jane Grant.

When the war ended, Ross followed her back to Manhattan and took an apartment with army pal John T. Winterich, at 56 West 11th Street in the Village. The men restarted their weekly poker game that had been wildly popular in Paris. Captain Frank Adams had named it the Thanatopsis Inside Straight and Pleasure Club, and the game lasted twenty years. In March 1920, fewer than six months later, Ross and Grant married. Woollcott made all the arrangements for the wedding—then sent them a bill for his services.

While Grant worked on the Times, Ross took various editorial jobs. When the Round Table first met in June 1919, Ross attended as Woollcott’s guest. Here he met future New Yorker contributors, such as Marc Connelly and Dorothy Parker. After he died Parker remembered him thus:

His improbabilities started with his looks. His long body only seemed to be basted together, his hair was quills upon the fretful porcupine, and his teeth were Stonehenge, his clothes looked as if they had been brought up by somebody else. Expressions, sometimes several at a time, would race across his countenance, and always, especially when he thought no one was looking, not the brow alone but the whole expanse would be corrugated by his worries, his worries over his bitch-mistress, his magazine. But what he did and what he caused to be done with The New Yorker left his mark and his memory upon his times.

Ross and Grant lived with Heywood Broun and Ruth Hale during the summer of 1920. Then, for two years, they resided above a machine shop at 231 West 58th Street, near Columbus Circle. When the couple scraped together enough money, they purchased a house that became legendary in literary and theatrical circles: 412 West 47th Street.

In 1924, Ross and Grant developed a proposed “humorous weekly” magazine, relentlessly showing the mock-up to investors and contributors. Eventually the pieces fell into place, and in the summer of 1924 they secured offices at 25 West 45th Street. Ross was in business.

The magazine had a rocky start, but Ross’s vision never wavered. Among the early editors was Stanley Walker, legendary Herald Tribune city editor, who worked alongside Ross. Walker wrote that The New Yorker “demonstrated that a smart, casual style, coupled with a sophisticated viewpoint, does anything but repel the reader. . . . It has made money by treating its readers, not as pathological cases or a congregation of oafs, but as fairly intelligent persons who want information and entertainment.”

Ross toiled like a workhorse on the magazine for the next quarter of a century. He ran his health into the ground and gave himself ulcers, stomach problems, and high blood pressure. His marriage to Grant suffered, and, like so many other couples associated with the Vicious Circle, they split. In 1930, following the divorce, Ross rented an apartment at 277 Park Avenue, ten minutes from the office. It didn’t last long: He violated his lease by having “persons of the opposite sex” as overnight guests, and was asked to leave. Ross took solace in poker and fishing trips, always trying to avoid the high life that his magazine extolled.

His second marriage came in 1934 to Marie Françoise “Frances” Elie, a Frenchwoman twenty years his junior. The couple had a daughter, Patricia, in 1935, but the marriage lasted fewer than five years. He remarried, for the third and final time, in 1940. Ross was forty-eight years old, and Ariane Allen, a party girl and failed actress-model, was twenty-five. The couple split their time between an apartment at 375 Park Avenue and Ross’s house in Stamford.

In life he toiled and struggled, but in death Ross entered the pantheon of American editors, considered one of the greatest of the twentieth century.

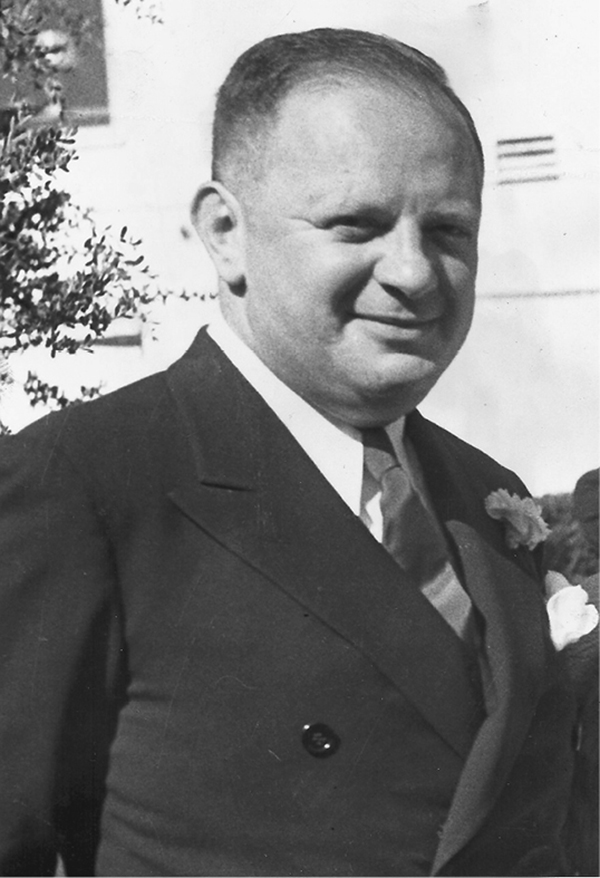

Arthur H. Samuels

A member of the Vicious Circle who has fallen into obscurity, Arthur H. Samuels was a musician, reporter, editor, and publicity genius who helped Ross and Grant launch The New Yorker. Ross, who abhorred personal conflict, infamously fired him via cablegram while Samuels was on an ocean liner. Samuels went on to edit Harper’s Bazaar, poaching some of Ross’s best talent. With a beautiful wife who was a retired silent-film star, Samuels was a fixture on the city gossip pages.

In early 1934 columnist O. O. McIntyre wrote:

Samuels is blond and one of the few chieftains of the editorial sanctum with real musical ability. . . . Samuels was a pianist of concert caliber. His repertory ranges from his own back-room arrangement of “Frankie and Johnny” to the most difficult Bach. He is in his thirties and one of the few able to winnow a story or poem from the coy and reluctant Dot Parker.

A savvy editor and sharp publicity man, Arthur Samuels was another of the Round Table men who married a movie star. ◆ ◆ ◆

Samuels was born on April 15, 1888, in Hartford, Connecticut. His father died when he was a boy, and he supported his mother. He worked his way through Princeton, and moved to New York in 1909, becoming a reporter at the New York Sun and traveling with former president Theodore Roosevelt as the paper’s special correspondent. On the Sun he met Frank Sullivan, also a beat reporter, who became his best friend. From 1913 to 1917, he lived in Philadelphia and worked as the publicity manager of the Curtis Publishing Company in Independence Square. During the war he moved to Washington to work as an editor for the Food Administration. There he took charge of publicity for the Surgeon General’s office, raising awareness about better treatment for wounded soldiers and Marines.

Samuels returned to Manhattan after the war, and for almost a decade was a partner in an advertising agency. When the Round Table began in 1919, he was thirty years old and well liked by all. An accomplished pianist and amateur composer, he wrote the score to the 1923 musical comedy Poppy for W. C. Fields and Madge Kennedy. The show ran at the old Apollo Theatre at 223 West 42nd Street for 350 performances, and Samuels made a tidy sum from the sheet music sales.