Raising the Curtain

Broadway’s Golden Age and Its Round Table Stars

When I was born I owed twelve dollars.

—George S. Kaufman

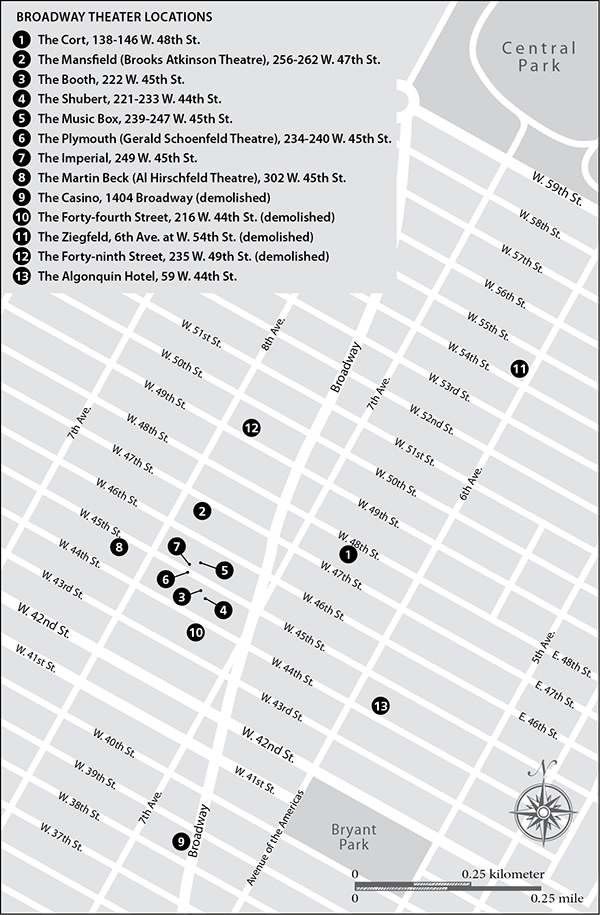

The single unifying element among almost all members of the Round Table was the live theater business. Sitting at the table at any given point was at least one person who made his or her living on Broadway. Some wrote the shows that others acted, while across the table critics lay in wait to tear both of them down. Press agents drummed up publicity and ticket sales, so they sat next to the newspaper columnist who needed backstage gossip for the next day’s edition. Directors and producers, the men behind the scenes, were among the most powerful in the city. Young actresses floated into the hotel dining room and held their own at the table. All bonded over grilled chicken and potatoes on West 44th Street.

Broadway was vastly different in 1920 from what it has become today. Audiences then were considerably larger; live theater had no competition from radio and television. Motion pictures were still silent, and their impact was just beginning to register. The simplest figure to know is the number of Broadway playhouses in operation then: 76 “legitimate” theaters. In 2014, the number was 40. Other stats: The average number of plays (dramas, musical comedies, revues, and operettas) produced annually on Broadway in 1920 was 225. In 1927, the peak year for live theater in the decade, 268. In the 2012–13 season: just 46 new productions. In the Twenties, sometimes as many as five new shows opened on the same night.

The Theater District was the Vicious Circle’s stomping ground. Within ten blocks lay the supper clubs, speakeasies, hotels, and some of the newspapers. After World War II, the theater business contracted. Many venerable stages became movie theaters, and some ended life showing X-rated films in the Sixties and Seventies. As real estate values rose, the buildings fell to the wrecking ball. Today, the former locations of scores of theaters have become office buildings and hotels.

1. The Cort

The Cort is the only surviving, still active, legitimate theater designed by Thomas W. Lamb. ◆ ◆ ◆

Built by West Coast theater owner John Cort and designed by Thomas W. Lamb in the style of the Petit Trianon at Versailles, the 1,084-seat Cort opened in December 1912. Merton of the Movies—one of the biggest hits for the Kaufman and Connelly team—played there for 392 performances, from November 1922 to October 1923. Kaufman famously cracked, “Satire on the stage is what closes on Saturday night,” but the show, a satire about a shy, movie-mad grocery clerk who goes to Hollywood and becomes a silent-film star because he is such a terrible actor, was a smash. In 1987, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the French neoclassical interior and exterior of the theater as landmarks.

2. Mansfield Theatre (Brooks Atkinson Theatre)

The 1,044-seat theater was originally named for nineteenth-century actor Richard Mansfield. Herbert J. Krapp, architect on half a dozen other theaters from the era, designed it in 1926. It has a striking interior, due in part to one of the interior designers having been the former architect to Czar Nicholas II.

Marc Connelly won his only Pulitzer Prize for The Green Pastures, which played at the Mansfield for 640 performances in 1930–31. Adapting a book by Roark Bradford of sketches and stories picked up from plantations in the Deep South, Connelly retold the Old Testament through the eyes of southern blacks with a large, all-black cast. Benchley, writing in The New Yorker, said: “I do not ever remember crying before over the thing that made me cry almost continuously as The Green Pastures. I cried because here was something so good. . . . You have never seen anything like The Green Pastures in the theater before, and you are not likely to see anything like it again, for it could not be imitated.”

The theater was renamed in 1960 for the Times theater critic Brooks Atkinson.

Many members of the cast of The Green Pastures lived in Harlem. ◆ ◆ ◆

3. Booth Theatre

Peggy Wood and Clifton Webb in Blithe Spirit. ◆ ◆ ◆

The Booth is one of the oldest and most intimate theaters on Broadway. Named for actor Edwin Booth—brother of Lincoln assassin John Wilkes Booth—it opened in October 1913. Henry B. Herts, architect of the neighboring Shubert Theatre, designed it in the Italian Renaissance style. The 800-plus-seat Booth was built for drama and comedies and has a warm atmosphere. It also has an unusual feature: a wall between the auditorium and the entranceway to dampen street noise from West 45th Street.

George S. Kaufman approached Edna Ferber about adapting a 1922 short story she’d written, “Old Man Minick,” about a tightly knit Chicago family. Ferber jumped at the chance, and the pair banged out a script for Minick, their first theater collaboration. “I didn’t think there was a play in Minick, and I don’t to this day,” Ferber wrote afterward. When the play opened in September 1924, with Antoinette Perry as Lil Corey, reviews were good . . . except in the Times: “Woollcott loosed vials of vitriol out of all proportion to the gentle little play’s importance,” she recounted. The play ran for 141 performances until January 1925. Although not a big success, it showed that Kaufman and Ferber could work together, which they did again.

Another Round Table member starred in a smash hit at the Booth. Noël Coward tapped Peggy Wood for the role of Ruth Condomine in Blithe Spirit when the play transferred from London to New York. The comedy ran for more than 650 performances between 1941 and 1943. The Booth attained city landmark protection in 1987.

4. Shubert Theatre

Sam Shubert, for whom the theater is named, died tragically. ◆ ◆ ◆

Named for producer Sam S. Shubert, killed in a 1905 Pennsylvania train wreck, the Shubert opened fourteen days before the Booth in October 1913. In time, Shubert’s brothers, Lee and Jacob, built a theatrical empire that still stands today. Henry B. Herts designed the 1,400-seat Venetian Renaissance theater at the same time he worked on the Booth, and decorated the Shubert with elaborate plasterwork and murals.

The first play to win a Pulitzer Prize in the Shubert was Robert E. Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight in 1936. An antiwar satire set in a hotel in fascist Italy on the eve of World War II, the show was a sensation, and ran for three hundred performances in 1936–37, starring Alfred Lunt, Lynn Fontanne, and Sydney Greenstreet. Sherwood wrote later: “It was completely American in that it represented a compound of blank pessimism and desperate optimism, of chaos and jazz.”

In 1996, the Shubert was restored to its former glory and its central ceiling mural re-created. In the lobby, look for the somber framed portrait of Sam S. Shubert, who died at age twenty-eight.

5. Music Box Theatre

The Music Box Theatre has four Federal Revival columns in front of what was once a smokers’ porch. ◆ ◆ ◆

Designed by C. Howard Crane and E. George Kiehler and built for Irving Berlin and producer Sam H. Harris, the Music Box Theatre opened in September 1922 with Irving Berlin’s Music Box Revue. Moss Hart described it as everyone’s dream of a theater.

In the Thirties, George S. Kaufman had a string of hits here. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind’s Of Thee I Sing was the first musical to win a Pulitzer Prize, and it happened here in 1931. With Edna Ferber, Kaufman collaborated on Dinner at Eight in 1932, which ran for 232 performances, and Stage Door in 1936, for 169 shows. But his biggest hit of all was based on his old boss, Alexander Woollcott. With Moss Hart, Kaufman cowrote The Man Who Came to Dinner, which opened in October 1939 and ran for 739 performances.

The Music Box was designated a city landmark in 1987.

6. The Plymouth Theatre (Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre)

Herbert J. Krapp, also the architect of the Longracre, designed the Plymouth in 1917, the patterned brickwork on the exterior its most significant architectural element.

Laurence Stallings and Maxwell Anderson were both working at the New York World when they decided to collaborate on a play. Stallings, who’d lost a leg in combat as a Marine, knew he wanted to write an antiwar drama. The pair cowrote What Price Glory? for producer-director Arthur Hopkins, the first play to use the profanity-laced speech of soldiers. Its grim view of war riveted audiences, and it was a hit at the Plymouth in September 1924, running for 433 performances and landing its playwrights Hollywood contracts.

Another of the many successful shows on the Plymouth stage was Robert E. Sherwood’s 1939 Pulitzer Prize winner, Abe Lincoln in Illinois, with Raymond Massey as the sixteenth president.

This theater was declared a city landmark in 1987. After eighty-eight years as the Plymouth, it was renamed in 2005 for Gerald Schoenfeld, a lawyer and chairman of the Shubert Organization.

7. Imperial Theatre

The Imperial opened in 1923 as a musical comedy theater with a capacity of more than 1,600 seats, also designed by the Shubert brothers’ go-to architect, Herbert J. Krapp.

Here George S. Kaufman had one of his rare flops. The 1933 musical Let ’Em Eat Cake was a sequel to Of Thee I Sing, the latter a hit in 1931. With lyrics by Ira Gershwin and music by George Gershwin, it had the same cast and characters as the previous show but was darker, and its Depression themes didn’t win over audiences.

In 1987 the city gave landmark status to the interior but not the exterior.

8. Martin Beck Theatre (Al Hirschfeld Theatre)

Lynn Fontanne as Elena and Alfred Lunt as Rudolph Maximilian von Hapsburg in Reunion in Vienna. ◆ ◆ ◆

Vaudeville mogul Martin Beck planned one of the grandest of all Broadway playhouses. He tapped noted San Francisco architect G. Albert Lansburgh to create a Moorish-inspired building with elaborate, Byzantine-style details. Painter Albert Herter embellished an Arabian Nights theme so that theatergoers would forget they were sitting in Hell’s Kitchen. Lansburgh, who later designed the El Capitan in Hollywood, built the playhouse like a movie palace. Beck wanted to attract musical spectacles, so he added dressing rooms to hold a cast of 200. Originally the theater had around 1,200 seats; today it seats more than 1,400.

Robert E. Sherwood wrote Reunion in Vienna for Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, and it became one of the biggest hits of his career, playing at the Martin Beck for 264 performances from 1931–32. But the most famous anecdote about the Martin Beck involves Dorothy Parker. The erstwhile drama critic attended The Lake in 1933, a flop that featured a twenty-six-year-old Katharine Hepburn. As the legend goes—because the tale doesn’t appear in any published Parker reviews—a friend asked Parker what she thought of Hepburn’s performance. “She ran the gamut of emotions—from A to B.” The story got back to the actress, who years later admitted to making the sign of the cross whenever she passed the theater.

The Martin Beck received landmark status in 1987, its interior described as “unlike any other Broadway theater.” It was renamed in 2003 for cartoonist Al Hirschfeld.

9. Casino Theatre (demolished, 1930)

Russell Henderson caricature from the New York Evening Post, July 1924. ◆ ◆ ◆

A beloved playhouse on the corner of Broadway and 39th Street, the Moorish-influenced Casino opened in 1882 with about 900 seats. It was the first theater with a roof garden, the first lit entirely by electricity, and the first to feature a chorus line—the Florodora Girls in 1900.

In 1924, the Marx Brothers lit up Broadway in their first show, I’ll Say She Is, at the Casino. Critics took notice. One of them was George S. Kaufman, who wanted to work with them. Their first collaboration was the Marx Brothers’ second show, The Cocoanuts, with music and lyrics by Irving Berlin, which played at the Lyric Theatre for 276 performances and made huge stars of the brothers. Kaufman wrote the comedy based on a Florida real estate swindle and confidence men. Typical of Kaufman’s humor was a scene with Groucho, Chico, and a map: Chico thinks that “levees” is the Jewish neighborhood; Groucho tells him “Well, we’ll Passover that.” Harpo stole scenes with his silence and even played some of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue on his harp. In 2014, I’ll Say She Is was revived Off-Off-Broadway to mark the centennial of the brothers adopting their “-o” nicknames.

The Casino was demolished in 1930.

10. Forty-fourth Street Theatre (demolished, 1946)

The Forty-fourth Street Theatre opened in November 1912 as the Weber and Fields Music Hall, named by the Shuberts for the popular musical comedy team of the Gay Nineties. The duo had reunited after years of fighting, but two months after the theater was named in their honor, they split for good, so their names came off the building.

Shakespeare and musical comedies filled the nearly 1,500-seat house for thirty years. The Marx Brothers’ biggest Broadway hit, Animal Crackers, opened here in 1928. During World War II the theater hosted the Stage Door Canteen, a popular destination for service members to meet Broadway and Hollywood stars. Among the backers were Round Tablers Brock Pemberton and Peggy Wood. The final show was Leonard Bernstein, Adolph Green, and Betty Comden’s On the Town in 1945. The playhouse was demolished the next year to make way for an annex to the New York Times printing plant on 44th Street. Today a bowling alley, theme restaurants, and exhibition space stand in its place, but a bronze plaque marks the spot where the theater once stood.

11. Ziegfeld Theatre (demolished, 1966)

The Ziegfeld Theatre opened in January 1927. Will Rogers helped to dedicate the cornerstone for the playhouse, cofinanced by William Randolph Hearst and Arthur Brisbane. At year’s end, on December 27, 1927, a new era in Broadway began at the Ziegfeld. Edna Ferber’s Show Boat became the first musical production in which songs advanced the plot rather than delaying it. It was also the first time that white and black actors held the stage together in a serious show. In an era of “wonderful nonsense,” the musical contained challenging themes about race and compelling storylines about personal convictions. Show Boat ran for 572 performances and became an American classic. It has been revived half a dozen times and adapted as a motion picture three times.

While Show Boat achieved immortality, the theater that bore the name of Florenz Ziegfeld Jr. didn’t have a long life. It became a movie theater after the great showman’s 1931 death. In 1944, Billy Rose purchased the playhouse and briefly resumed live theater there. In the Fifties, NBC rented it for television productions, such as the Perry Como Show. It was demolished in 1966, and an office tower built in its place. Not long after, a movie theater was built next door and given the Ziegfeld name.

The Ziegfeld once grandly occupied the corner of Sixth Avenue and 54th Street. ◆ ◆ ◆

12. Forty-ninth Street Theatre (demolished, 1940)

Designed by Herbert J. Krapp, the Forty-ninth Street Theatre opened during Christmas week, 1921. The only reason to remember this Shubert-owned theater is that on its stage every Round Table member participated in a one-night revue, in which they all wrote, sang, and acted in all the parts.

At the time, the hit show at the playhouse was La Chauve-Souris, a Russian-style revue that ran for more than five hundred performances. The Vicious Circle thought it would be fun to take over the theater on a Sunday night and invite their friends to an original production. They patterned it after the Russian show, and with a laugh, called it No Siree.

On April 30, 1922, the program kicked off with Broun as master of ceremonies, followed by the all-star male chorus: F.P.A., Benchley, Connelly, Kaufman, Toohey, and Woollcott. The group put on a parody of Eugene O’Neill, called The Greasy Hag, which they camped up with music by Arthur Samuels and Jascha Heifetz. A parody of He Who Gets Slapped, called He Who Gets Flapped—performed by Sherwood and a chorus of dancing girls including some of the top young actresses—brought the house down.

For that evening, Dorothy Parker wrote “The Everlastin’ Ingénue Blues,” and another skit featured Harold Ross in a part that didn’t require him to take the stage, or even appear at all. When the curtain came down, one star emerged: Robert Benchley, who debuted his “Treasurer’s Report” there. The theater business audience had a grand time and remembered it as one of the highlights of the season.

Another victim of the Great Depression, the theater became a movie house in 1938, and in December 1940, fewer than twenty years after it opened, it was demolished. A hotel stands there today.

Under construction in 1921, the Forty-ninth Street Theatre was demolished within twenty years. ◆ ◆ ◆